1. Introduction

Alternative splicing occurs in approximately 95% of human genes [

1,

2] and plays a key role in phenotypic complexity, which increases with the extent of alternative pre-mRNA splicing [

3], as well as in the proteome [

4,

5]. Thus, it is possible to produce proteins with different structures and functions or to alter mRNA localization, translation or decay starting from a specific pre-mRNA [

6]. This relevant event is a critical step in the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression, a dynamic and flexible process mediated by different regulatory elements (such as

cis-acting and

trans-acting factors) [

7,

8,

9,

10] and additional molecular features, as well as RNA secondary structures [

11,

12] and chromatin structure[

13,

14], which are known to promote (

enhancers) or inhibit (

silencers) splicing activity to generate protein diversity. All these regulatory factors, regions and splice sites can be affected by mutations that can cause a variation in alternative splicing isoforms. Indeed, the misregulation of splicing due to mutations is implicated in many human genetic diseases (about 50%) [

15,

16], including several neurodegenerative diseases. Some of these are collectively classified as Tauopathies and are often associated with an imbalance of tau protein isoforms caused by splicing shortfalls. The consequence of the aberrant splicing is the presence of abundant tau deposits, called neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), in different regions of affected brains [

17,

18,

19,

20].

One of the diseases directly resulting from the misregulation of alternative splicing is Frontotemporal Dementia and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) (OMIM 600274) [

21]. FTDP-17 is caused by a wide range of mutations in the

MAPT (

Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau) gene (17q21.31; OMIM_157140; NM_016835) [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26], which encodes for tau protein. About half of these mutations can induce aberrant alternative splicing of exon 10, affecting the ratio of tau isoforms with four (4R) repeats (with exon 10) or three (3R) repeats (without exon 10), which is about 1

in the healthy adult human brain, [

27,

28], while in the pathological conditions this ratio increases to 2-3 [

29,

30,

31,

32]. This unbalanced ratio determines tau protein aggregation in NFTs, and the neuropathology described in families with FTDP-17 neurodegeneration.

Several strategies, using different quantitative assays, have been developed to increase the likelihood of discovering molecular therapeutics capable of modulating aberrant alternative splicing [

33,

34,

35,

36], however, these assays have limitations in terms of throughput and sensitivity.

Indeed, the identification of splicing regulators for a given alternative exon is generally very complex and laborious [

37], especially when the methods used are a single-output splicing reporter in which splicing changes were measured by the variation in expression levels of one of the two isoforms using biomolecular assays [

38,

39,

40]. Nevertheless, several studies have standardized the use of two-colour fluorescent minigene reporter systems in improving the dynamic range and distinguishing changes in alternative splicing from those due to transcription or translation [

41,

42], thus supporting the utility of such tools. One of the most important contributions to the development of efficient minigene reporter systems has been made by Peter Stoilov and colleagues [

43,

44] who showed that the splicing of a two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent reporter plasmid with Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau (MAPT) exon 10, can be modulated by bioactive compounds [

43]. The ability of this two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent reporter constructs to generate two alternative mRNA isoforms encoding different fluorescent proteins from a common pre-mRNA in a mutually exclusive manner provides an unprecedented sensitivity for detecting changes in alternative splicing events [

37,

45,

46].

Considering all the above information, our strategy was focused on developing a versatile, valid, rapid, and robust High Content Screening (HCS) assay to functionally confirm the role of splicing mutations in human genetic disorders and to identify potential molecular compounds for their effects on alternative splicing regulation. Therefore, we combined two strategies: the abovementioned two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent reporter plasmid assay, and the cell-based High-Content Imaging Technology, which provides higher sensitivity compared to the traditional plate reader-based assay.

To mimic the pathological alteration frequently observed in FTDP-17 we have introduced a dementia-related splice-switching point mutation (N279K)[

47] in the MAPT exon 10 two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent splicing reporter, which switches alternative splicing and thus favours the inclusion of exon 10. We then have applied image-based analysis using an HCS technology in the new HCS-Splice method, which focuses on parameter selection based on the quantification of fluorescent reporter intensity to monitor effects on altered splicing events caused by mutation insertion or drug treatment, such as exon 10-targeting siRNAs able to rescue the correct alternative splicing balance. Single-cell fluorescence measurement allows the calculation of multiple output parameters from a single well, providing reliable data from even small numbers of cells for kinetic assessments of alternative splicing. On a global scale, this work provides the basis for potential screening HCS splice methods, useful for drugs and small molecule therapies, that can be easily miniaturised for HTS assay applications to run in multiwell-plate formats ranging from 96 to 1536 wells.

2. Materials and Methods

The experiments described do not require IRB approval.

2.1. Mutagenesis of two-fluorescent reporter plasmid bearing exon 10

The two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent reporter plasmids created by Peter Stoilov and colleagues [

43,

44] PFLARE 5A MAPT-Exon 10 (PFLARE 5A-Tau10 WT) was used as template for generating the resulting plasmid PFLARE 5A MAPT-Exon 10 mutant (PFLARE 5A-Tau10 mut). The Quick-change II XL Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) was used to introduce exon 10 N279K mutation

(Chr17: 44,087,690 T>G),

according to the manufacturer's protocol.

In brief, the PCR amplification was performed in a final volume of 50 μL in a reaction mixture containing, as a template, the PFLARE 5A-Tau 10 WT plasmid and the following specific primers: mut_Exon10-For 5′-CCAAAGGTGCAGATAATTAAGAAG-3′ and mut_Exon10-Rev 5′-GTTGCTAAGATCCAGCTTCTTCTT-3′.

The sequences of both wild-type and mutant reporters and the exact point mutation position into the PFLARE 5A-Tau10 mut plasmid were verified by sequencing (BMR Genomics, Padova, Italy).

2.2. SH-SY5Y human cell line culture

Human dopaminergic neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) is a thrice cloned (SK-N-SH -> SH-SY -> SH-SY5 -> SH-SY5Y) subline of the neuroblastoma cell line SK-N-SH. The SH-SY5Y cells were grown in a 1:1 mixture of Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium and F12 Medium (Gibco, Life Technologies) supplemented with 2 mM L-Glutamine (Gibco, Life Technologies), 100 U/µL Penicillin/Streptomycin (Gibco, Life Technologies) and 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Gibco, Life Technologies). All cell cultures were grown in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2.

2.3. SH-SY5Y: Transfection and Cotransfection

The day before transfection, 5 × 104 cells were seeded onto 24-multiwell plates (Corning, NY) and grown in 0.5 ml supplemented medium without antibiotics at 37°C and 5% CO2. Transfection experiments were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life-Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). with a ratio of DNA (ng): Lipofectamine 3000 (μL) of 1:2 in Opti-MEM medium (Gibco, Life Technologies), and cells confluence of maximum 70%. An amount of 0.5 μg of each plasmid, PFLARE 5A-Tau10 WT and PFLARE 5A-Tau10 mut were employed in both experiments of transfection and cotransfection.

The cotransfection assays were carried out by using siRNA-Tau10 and siRNA Scramble molecules (Eurofins Genomics) at different concentrations: 10nM, 25nM, 50 nM and 100 nM. The control cells were treated with medium non-transfected (NT), Lipofectamine 3000 only (Mock), WT or mutant two-fluorescent reporter plasmid and cotransfected with non-targeting siRNA (siRNA Scramble). Following transfection, the cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48 hours.

2.4. High Content Imaging Acquisition

At 48 hours of transfection or cotransfection, the fluorescent signals from each plasmid (PFLARE 5A-Tau10 WT and PFLARE 5A-Tau10 mut) were analysed on live cells using the Operetta High-content Imaging System (PerkinElmer, Monza, Italy). The SH-SY5Y live cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 1mg/mL of Hoechst 3342 fluorescent dye (ThermoFisher Scientific), added to 0.5 ml of supplemented DMEM (Gibco, Life Technologies) for 20 minutes at 37°C. This step was needed to enable nuclei counterstain and subsequent total analysis. At the end of incubation, the cells were washed and DMEM medium without phenol red was supplemented to each well (Gibco, Life Technologies). The total cell numbers, viability, transfection efficiency, and fluorescence intensity measurements were estimated using a 20X LWD objective. The acquisition step was performed under 5% CO2 and 37°C conditions and in a wide-field mode in combination with three different filters. The Hoechst 33,342 was detected with a dedicated combination of filters (excitation: 360-400 nm, emission: 410-480 nm), while the combinations of the filters for Alexa Fluor 488 (GFP: excitation: 460-490 nm, emission: 500-550 nm), and Alexa Fluor 594 (RFP: excitation: 560-630 nm, emission: 580-620 nm), were used to measure both the PFLARE 5A-Tau10 WT and PFLARE 5A-Tau10 mut reporters’ fluorescent intensities.

A minimum of 12 images per well were acquired to score enough objects for each condition tested.

2.5. High Content Imaging System Analysis

The Harmony software 4.1 (PerkinElmer, Monza, Italy) was used for the image analysis. The “Select Population” feature of the software allowed us to set a threshold of fluorescence intensity to identify the sub-population of transfected cells. The SH-SY5Y cells transfection efficiency analysis was carried out taking into consideration both GFP and RFP positive cells number, compared to the Hoechst33342 positive total number of cells. At the same time, the two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent intensity ratio of the cells was measured to evaluate the differential expression values between the PFLARE 5A-Tau10 WT and PFLARE 5A-Tau10 mut reporters’ fluorescent plasmids and therefore between cell populations treated and untreated with siRNAs.

In brief, the live cell images acquired were segmented and analyzed by Harmony High-Content Analysis Software (PerkinElmer), according to the following workflow.

In the first step, the cells were identified using the most suitable algorithm based on nuclei segmentation, performed on the Hoechst33342 channel using the Find Nuclei building block. In the second image analysis step, assuming a homogeneous distribution of the GFP and RFP fluorescent signals in the live cells, the respective intensities were measured within a region of interest (ROI) around the nuclei, applying a Select Region block. In order to quantify the mean fluorescence intensity corresponding to the true transfected live cells, a double-threshold strategy to filter out the cells being either positive for G (GFP) or R (RFP) or the double G+R “Yellow” fluorescent signal was applied. A Select Population function was employed to classify each fluorescent cell population, G, R, and G+R. To define the splitting point between the population of fluorescent cells G, R, and G+R, an intensity threshold was determined based on the signal coming out from positive and negative control wells (not transfected cells). The resulting Intensity Threshold was used as a reference value to classify the three fluorescent cell subpopulations. Considering the transfected cells only, by the Find Results building block section the formula Ratio between the fluorescence properties of G and R mean intensity on a per-cell basis was calculated. The cell subpopulations were then classified as preferentially expressing GFP (G/R>J), RFP (G/R<K) or both the reporters G+R (K<G/R<J), by applying a filter-based for the three different subpopulations. Feature outputs of the analysis protocol include total cell count, viable cells count, percentage of transfected cells, calculated over the total number of cells, the G/R median value of all the cells of the well, and the percentage of cells selectively expressing GFP (G/R>J), RFP (G/R<K) and both the reporters (K<G/R<J) (

Figure S2C). Batch analyses were carried out simultaneously for all biological experiments and the Z’ value (Z’ Prime) statistical method was applied to measure the assay robustness.

2.6. Validation of HCS-Splice: RNA extraction and Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis

At the end of the HCS-Splice analysis, the RNA was extracted using Trizol Reagent (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was treated with DNase (TURBO DNA-free Kit; Life Technologies), and concentrations were estimated by Nano-Drop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Nano-Drop Technologies, Wilmington, NC). Five hundred nanograms of extracted RNA were reverse transcribed into cDNA using dT18 oligonucleotides and the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Semiquantitative RT-PCR reactions, to evaluate the expression of exon 10, were carried out in 25 μL final volume in a reaction mixture containing 50 ng of cDNA and 1U Taq DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems by Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s protocols. After 5 minutes of denaturation at 95° C, amplification was carried out for 30 cycles (30 seconds at 95° C, 40 seconds at 60° C, and 1 minute at 72° C), with a final extension for 7 minutes at 72° C.

The endogenous MAPT expression levels were detected using a pair of specific primers: human MAPT: TAU-Ex9 For 5’-CTGAAGCACCAGCCGGGAGG-3’; TAU-Ex13 Rev: 5’TGGTCTGTCTTGGCTTTGGC-3’. The primers discriminate between the two-alternative endogenous MAPT transcripts (E10+ and E10-), producing two different amplicons: 275 bp for the isoform without E10 (E10-) and 368 bp for the isoform with E10 (E10+). To analyze the transcripts come from the PFLARE 5A-Tau10 WT and PFLARE 5A-Tau10 mut minigene reports the semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed using primers:

Exon 1 Bgl For 5’-AAACAGATCTACCATTGGTGCACCTGACTCC-3’, and EGFP Rev 5’-CGTCGCCGTCCAGCTCGACCAG-3’. An amplicon of 207 bp for the isoform without E10 (E10-) and an amplicon of 300 bp for the isoform with E10 (E10+) were obtained.

An amplicon of 650 bp from the Beta Actin region was amplified using primers Beta-Actin For 5’-AGACGGGGTCACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTA-3’ and Beta-Actin Rev 5’-CTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGCACGATGGAGGG-3’ was used as a control (Housekeeping gene). Amplified products were loaded in 2% agarose gel electrophoresis performed in TAE 1X running buffer and visualized with Atlas ClearSight (5%) (Bioatlas). 1 kb plus DNA ladder (Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific) were run with amplified products to keep track of the band dimension. Densitometric analyses were carried out with Image Lab 2.0 software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data from

three independent

biological replicates, with three technical replicates for each, were represented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Data were compared using Student’s t-test and One-way analysis variance (ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons tests (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA.

www.graphpad.com). Imaging batch analyses were carried out simultaneously for all biological experiments and the Z’ Prime statistical method was applied to monitor the assay accuracy and sensitivity. The Intensity Threshold was defined by using the Z formula:

µ = mean; σ = Standard deviation

The Z-values above ~ 0.4 are considered sufficient for screening assay, and Z’ values above ~ 0.6 are considered robust values. The theoretical maximum Z’ value is 1.0 (= no noise), however, HCS assays with a Z′ factor of 0.5 indicate that the assay is enough robust to identify molecules activity reliably [

48]. Statistical significance was set to p < 0.05 and it is denoted with asterisk (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001).

3. Results

3.1. HCS-Splice workflow

A new image-based analysis method, HCS-Splice, has been optimised to expand our ability to find new molecular therapies to modulate aberrant alternative splicing. We have developed our analysis method using PerkinElmer High-Content Screening (HCS) and High-Content Analysis (HCA) technologies. Indeed, the automated combination of image acquisition (Operetta System) and analysis (Harmony Software) made it possible to extract quantitative multi-parametric data from cellular samples even at the single-cell level, allowing several questions to be answered simultaneously.

Considering the time, cost and process optimisation of screening, the multi-step HCS-Splice workflow can be summarised into four essential canonical phases leading to drug validation in

in vitro systems. These steps include target and hit identification (

in silico), screening in cell system models (

in vitro), data acquisition and image analysis in the building block modality (

in silico), and hits identification and validation (

wet lab and in silico processes) (

Figure 1A). The designed HCS-Splice method could therefore be used,

in vitro, for numerous applications in different areas of drug or molecular therapeutic discovery, such as oncology, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, where we need to analyse the most complex cellular models, reliably discriminate phenotypes, and turn biological data into knowledge.

3.2. Exon 10 site-directed mutagenesis of a two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent reporter

We implemented the HCS method by using a two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent reporter plasmid (PFlare5A-Tau10 WT) generated by Peter Stoilov and colleagues (

Figure 1B) [

43]. To recapitulate a splicing mutation (N279K) described in Frontotemporal Dementia and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) we introduced a T>G point mutation in the exon 10 sequence, by site-directed mutagenesis (

Figure 1C). Indeed, under pathological conditions, the presence of the N279K point mutation in the human

TAU gene sequence affects splicing allowing exon 10 to be more frequently incorporated into tau transcripts, thus increasing the expression and production of the tau isoform protein 4R compared to the 3R [

24,

25,

47,

49,

50]. The presence of the N279K mutation in the PFlare5A-Tau10 mutant (PFlare5A-Tau10 mut) fluorescent reporter plasmid compared to the PFlare5A-Tau10 wild-type (PFlare5A-Tau10 WT) sequence was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (

Figure S1A and S1B).

3.3. Development of an image-based HCS-Splice method using two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent reporter plasmids transfected into SH-SY5Y cells

To assess whether the PFlare5A-Tau10 mut fluorescent reporter plasmid was able to recapitulate aberrant alternative splicing of exon 10 in the presence of the N279K mutation and whether it was suitable to implement our new HCS-Splice method, we transiently transfected either PFlare5A-Tau10 WT or PFlare5A-Tau10 mut into Human dopaminergic neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (

Figure 1A and

Figure 2A). These cells present splicing

trans-acting factors that allow for the inclusion of exon 10 in 30% of endogenous MAPT transcripts (

Figure S2A).

After forty-eight hours of transfection, images of the SH-SY5Y cells were acquired and analysed using a High Content Screening method (Operetta, PerkinElmer) and cell viability was first measured (

Figure S2B).

Therefore, by using the High Content Imaging through the automated fluorescent microscope (Operetta, PerkinElmer), images were acquired from multi-well plates, in live cells condition, under CO

2 controlled (5%) and Temperature (37°C), using a 20X LWD objective in wide-field mode, in combination with filters for Hoechst33342 (excitation: 360–400 nm; emission: 410–480 nm), Alexa Fluor 488 (excitation: 460–490 nm; emission: 500–550 nm), and Alexa Fluor 594 (excitation: 560–630 nm; emission: 580–620 nm). During the automated image acquisition, the Operetta microscope was allowed to perform a fully automated measurement of the different fluorescent intensity signals, Hoechst, RFP and GFP expressed by transfected SH-SY5Y cells (

Figure 2A).

In a second step, the fully automated analysis module Harmony 4.1 was used to quantify outcome signals of PFlare5A-Tau10 mut compared to PFlare5A-Tau10 WT fluorescent reporter plasmid. The image analysis workflow includes sequential steps that play a relevant role in the multi-step HCS-Splice method. A brief flowchart of the image analysis sequence is shown in

Figure 2B: at first, the pixel gradient of the Hoechst image was segmented to define the individual nucleus of every single cell. To assess the ability to detect the cytoplasmic GFP, RFP and MERGE region at the single cell level, and after clustering at the population level, the fluorescence intensity signal for both Alexa Fluor 488 and 594 channels was segmented and defined around the nuclear population and the fluorescence intensities were measured both within the cells and in the background ring region surrounding each cell. The background corrected fluorescence intensity was used as a readout to define the objects of interest, the “True cell populations”.

Subsequently, the Select Population building block allowed us to classify three subpopulations from all the “True cell populations” related to the different fluorescence signals. The machine learning algorithms based on two proprieties, Filter by Property and Linear Classifier, selected the key parameters necessary to set thresholds based on the intensities of RFP and GFP fluorescence of the objects of interest (

Figure S2A).

This step allowed the generation of a scatter plot showing the distribution of individual cells in each well carrying one of the two-colour (GFP or RFP) fluorescent reporters (PFlare5A-Tau10 WT or PFlare5A-Tau10 mut) (

Figure 3A). The thresholds values, K=2 (lower threshold) and J=5 (upper threshold) were chosen based on the scatter plotter, and three different subpopulations were identified: 1) the GFP-positive cells, which have a G/R parameter higher than 5 (J threshold); 2) the cells that predominantly express RFP, which have a G/R lower than 2 (K threshold); 3) the cells in which RFP and GFP are expressed at roughly the same amounts which have a G/R parameter between 2 and 5 (K <G/R<J) (

Figure 3A).

This single-cell classification allowed us to follow the splicing of MAPT exon 10 since the GFP population corresponds to cells in which the majority of report transcripts are devoid of exon 10, the RFP population corresponds to cells in which the majority of reporter transcripts contain exon 10, and the “Yellow” population, which shows equal levels of GFP and RFP fluorescence, has both report splicing variants. Indeed, the selected read-outs of the quantitative analysis of the two reporter plasmids showed that the presence of the N279K point mutation in the PFlare5A-Tau10 mut alters the fluorescence signals from a relatively low level of RFP to a very high level due to the inclusion of exon 10 (the characteristic hallmark of FTDP-17) (

Figure 2A and

Figure 3A,B).

In particular, SH-SY5Y cells transfected with PFlare5A-Tau10 mut compared to the PFlare5A-Tau10 WT fluorescent reporter plasmid showed, as expected, a shift in the proportions of the three sub-populations expressing either RFP-E10+, GFP-E10- or both "Yellow- E10+/E10-". The RFP cells increase from ~ 5% RFP to ~ 58% of the total cells, while the GFP cells decrease from ~ 10% GFP to ~ 5%. The population expressing at the same time both E10+ and E10- report transcript "Yellow" simultaneously decreases from ~ 82% YFP to ~ 43% (

Figure 3B).

3.4. HCS-Splice data validated using Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was performed, as described in Materials and Methods, to validate HCS-Splice image-based results (

Figure 3C). As schematically shown in

Figure 1B, alternative splicing of exon 10 results in the production of two different splice isoforms (E10+ and E10-). The presence of exon 10 in the reporter PFlare5A-Tau10 transcript results in a 300 bp amplicon (E10+), whereas amplification of the reporter transcript without E10 results in a 207 bp amplicon (E10-). As the reverse primer anneals to the reporter-specific portion of the RNA transcribed from the GFP cassette (Materials and Methods section), endogenous tau mRNA is not amplified by this primer pair.

Densitometric analysis of each band relative to the two different isoforms (E10+ and E10-), normalized using the housekeeping gene Beta Actin (650 bp), showed that the level of containing exon 10 transcript (E10+) increased from ~ 35% in WT to ~ 85% in the mutant reporter plasmid (P < 0.001), in accordance with the increase in RFP signal observed with image analysis (

Figure 3B).

At the RNA level, we observed that the N279K mutation was able to increase the exon 10 levels of about 2.5-folds compared with the PFlare5A-Tau10 WT (

Figure 3C), as reported in FTDP-17 patients [

51,

52]. We were able to understand that the level of endogenous exon 10 mRNA expression was comparable to levels observed by transfecting the reporter PFlare5A-Tau10 WT (~ 35%). Therefore, to improve the HCS-Splice methods to monitor the slight variations of splicing induced by potential therapeutic compounds during screening,

in vitro, we used our two-colour PFlare5A-Tau10 mut fluorescent reporter plasmid.

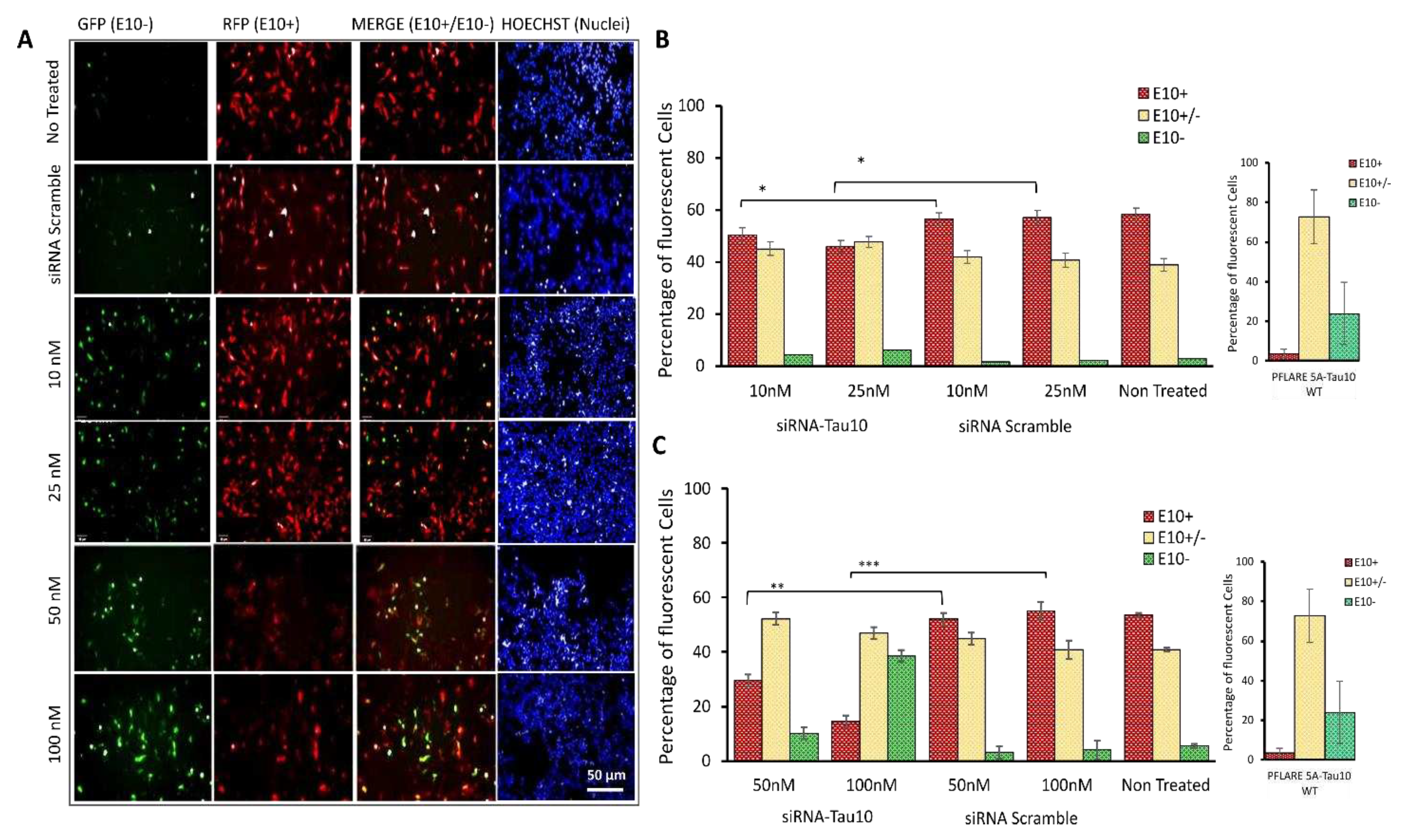

3.5. HCS-Splice method validation by using the siRNA molecules modulating the exon 10 splicing

To investigate the potential of our HCS-Splice method to effectively identify drugs or molecules that modulate splicing, a siRNA molecule targeting MAPT exon 10 (siRNA-Tau10) and a control siRNA (siRNA-Scramble) were designed. Wild-type and mutant two-fluorescent plasmid (PFlare5A-Tau10 mut and PFlare5A-Tau10 WT) (

Figure 1B) and siRNAs (siRNA-Tau10 and siRNA Scramble) were transiently co-transfected into SH-SY5Y cells in 24-wells plates. This plate format was chosen to allow the recovery of a sufficient number of cells at the end of the assay after the image-based analysis, for downstream processing for molecular analysis, such as semi-quantitative RT-PCR. The seeding density of cells can significantly affect high-content analysis. Therefore, it is recommended that a good balance be achieved between a high density for statistically meaningful results and a low density for robust cell detection. The efficacy of siRNA-Tau10, designed to silence exon 10-containing transcripts, was analysed in HCS-Splice at different concentrations ranging from 10 nM to 100 nM, in co-transfection with 0.5 μg of PFlare5A-Tau10mut (

Figure 4).

Dose-dependent reduction of the exon 10 isoform, E10+, was observed in PFlare5A-Tau10mut -transfected SH-SY5Y cells treated with siRNA-Tau10, relative to controls (

Figure 4A). While the percentage of red cells (RFP-E10+ isoform) decreases, there is an increase in the percentage of green cells, indicating the selective degradation of the alternative transcripts containing exon 10 (RFP-E10+): treatment with 10 nM of siRNA-Tau10 resulted in a slight reduction of the red population by ~ 5% compared to scramble control (P < 0.05). A concentration of 25 nM reduces red cells by ~ 15% (P < 0.05). Concentrations of 50 nM and 100 nM led to a reduction of ~ 25% (P ≤ 0.01) and ~ 45% (P ≤ 0.001), respectively. This gradual decrease of red cells was accompanied by a specular increase in green cells compared to scramble control (5%, 5%, 7% and 35%, respectively). Furthermore, we observed a slight increase of ~ 5-10% in yellow cells, compared to scramble control (

Figure 4B).

In a cotransfection experiment in SH-SY5Y cells with PFlare5A-Tau10 WT and siRNA-Tau10 (50 nM and 100 nM respectively), we observed an increase in the percentage of green cells (

Figure S3 A) and a decrease of yellow cells. However, when transfected with the WT reporter, a lower proportion of cells express only RFP in comparison with cells transfected with the mut reporter. Therefore, the assay showed a limited dynamic range for detecting exon 10 reduction in the context of PFlare5A-Tau10 WT (

Figure S3B).

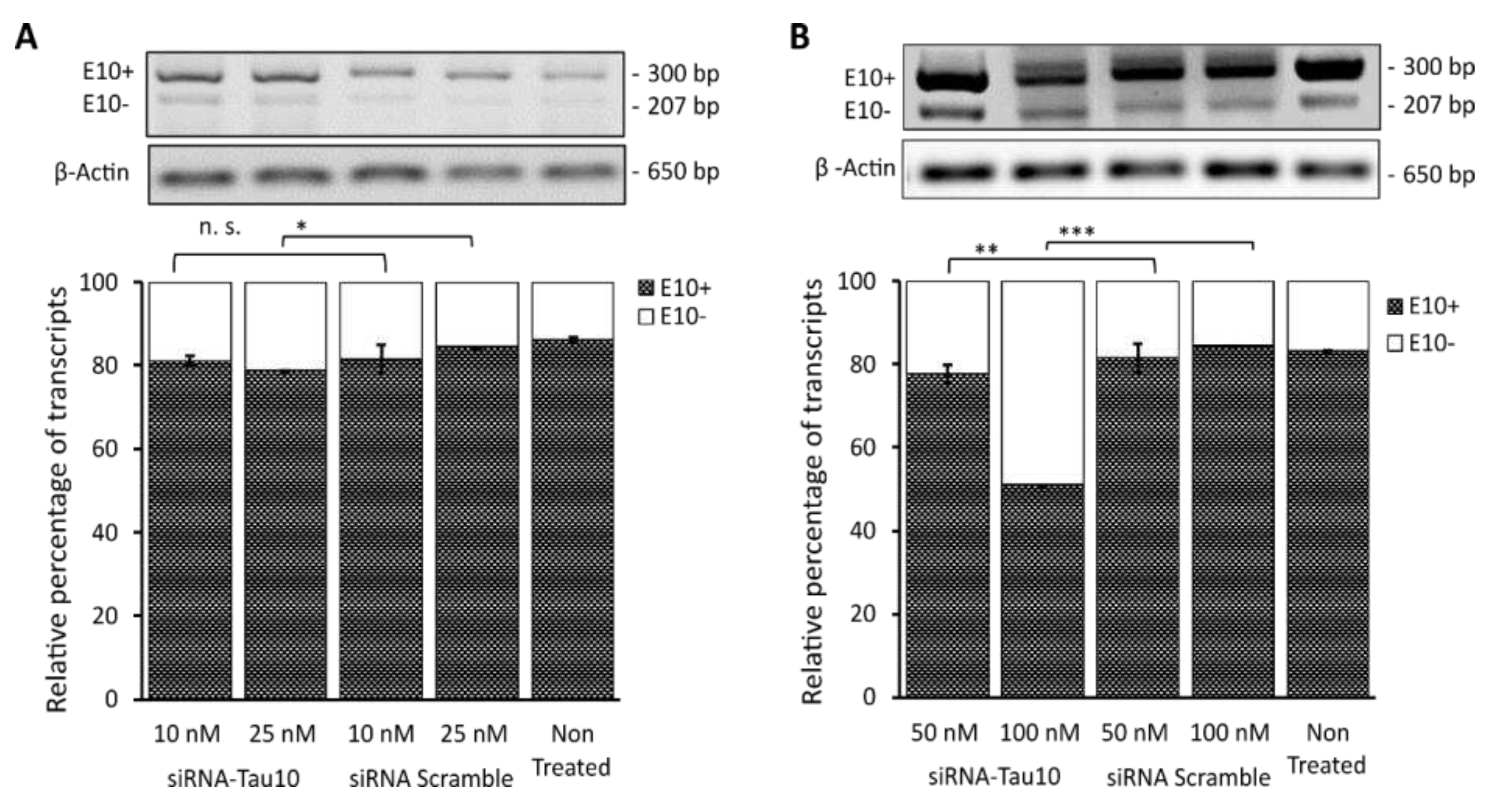

3.6. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis to validate the effects of the siRNA after HCS-Splice assay

As a final step, a semiquantitative RT-PCR assay was carried out, to validate the data obtained by the HCS-Splice image-based assay. Total RNA was extracted from the SH-SY5Y cell samples previously described and analysed. Following the cDNA synthesis, semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed to investigate the effects of siRNA-Tau10 treatment at concentrations ranging from 10 nM to 100 nM (

Figure 5).

Densitometric analysis showed that the siRNA-Tau10 induced depletion of transcripts containing exon 10 (E10+) in a dose-dependent manner, confirming the results obtained by the HCS-Splice methods. Indeed, each band relative to the two different isoforms (E10+ and E10-), normalized using the house-skipping gene Beta Actin (650 bp), showed that upon treatment with 10 nM there is no significant difference between the level of E10+ compared to the siRNA scramble control (p=n.s.), whereas, at a concentration of 25 nM, we observed a slight decrease of E10+ by ~5% (P < 0.05) (

Figure 5A). Interestingly, we were able to gradually decrease the level of E10+ by almost ~10% (P ≤ 0.01) after treatment with 50nM and by ~35% (P ≤ 0.001) by using the siRNA-Tau10 at a concentration of 100 nM (

Figure 5B). The control siRNA scramble at different concentrations did not affect the E10+ isoform, as expected (

Figure 5). The untreated mutant plasmid was compared with the different siRNA treatment conditions. These data further support and confirm the effects observed through the HCS-Splice image-based analysis.

4. Discussion

A key strategy for the in vitro identification and validation of molecular compounds with a specific pharmacological effect requires the application of high-throughput and high-content technologies. These technologies are based on a step-by-step pipeline process in drug discovery, which selects screening procedures and data analysis protocols in a highly accurate manner to obtain a stable and performing assay.

Here, we describe the new HCS-Splice method that combines the High-Content Screening (HCS) technology [

53,

54,

55] and the Splicing Report Minigene System assay [

41,

42,

56,

57] to identify molecules that modulate aberrant splicing outcomes. Indeed, taking advantage of the peculiar property of the two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent reporter plasmid produced by Stoilov and colleagues [

43], we have further enhanced the function of this system by incorporating a single base change (N279K FTD mutation) that disrupts the normal splicing of exon 10, increasing its inclusion [

51,

58,

59,

60,

61]. We have used this characteristic hallmark of Frontotemporal Dementia and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) to investigate the potential role of molecules, such as siRNAs, as drugs able to modulate the aberrant splicing of exon 10 in the neurodegenerative disease FTDP-17. Although neuroblastoma cell lines are still not easy to transfect, our protocol allowed us to obtain a sufficient transfection efficiency for both two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent reporter plasmids, PFlare5A-Tau10 mut and WT, and to monitor the effectiveness of siRNA molecules in modifying splicing outcome.

By combining the two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent reporter minigene system, transiently transfected into the SH-SY5Y cell line, with high-content image-based screening (HCS), we are able to restrict the analysis to only a subset of transfected cells, providing a powerful method for detecting of even rare events and individual cells. The traditional plate reader-based assay proposed by Stoilov [

43] involves a cell lysis passage and the recording of two-fluorescence intensity values resulting from the entire cell population in a given well, resulting in a single ratiometric readout (GFP/RFP) [

43]. Despite the robustness and suitability of the traditional plate-reader-based assay for high throughput screening, as reported in the literature, we believe that the HCS-Splice method reported here can take advantage of a per cell-based image analysis approach that allows the recording of additional data such as the number of cells per well, the shape of both nuclei and cytoplasm, single cell morphology, viability and transfection efficiency, which are helpful to monitor cytotoxicity due to the effects of compounds used in the study.

As part of the development of the minigene model for FTDP-17, we have introduced the N279K mutation into the PFlare5A-Tau10 WT two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent reporter plasmid developed by Stoilov and colleagues [

43,

44], thereby increasing the content of red cells from ~5% to ~58% (P ≤ 0.001) and decreasing green cells from ~10% to ~5% (P ≤ 0.01). This change is associated with a modification in the third subpopulation of cells containing both isoforms, exon 10+ and exon 10- (yellow cells which decrease from ~82% to ~43% (P ≤ 0.0001), reflecting a conversion of most cells to favour the production of exon 10+ in the two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent PFlare5A-Tau10 mut reporter plasmid (

Figure 3B).

The percentage of cells belonging to each subset of the population was calculated along with transfection efficiency (data not shown) and cell viability after transfection (48 hours) (

Figure S2B), both analysed using Harmony High-Content Imaging Software (PerkinElmer). These results were further validated by semiquantitative RT-PCR wherein the transcript containing exon 10 (E10+) increased by ~3-fold compared to the PFlare5A-Tau10 WT reporter plasmid (

Figure 3C), similar to what is reported in FTDP-17 patients. 24-well plates were chosen to recover sufficient cells at the end of the image-based analysis assay to perform downstream molecular analysis, such as semiquantitative RT-PCR. Cell seeding density can have a significant impact on high-content analysis. Therefore, a good balance between high density for statistically meaningful results and low density for robust cell detection is recommended.

The HCS-Splice method results and the semiquantitative RT-PCR assay data can be compared to observe the similarity of trends, but are not easily translatable the ones into the others, due to the following limitations: an image-based assay is quantitatively compared to the semiquantitative RT-PCR approach; furthermore, the image-based method is applied on 3 subset of populations (RFP-E10+, GFP-E10- and Yellow-E10+/E10-) whereas the semiquantitative RT-PCR is a measurement of only 2 different isoforms (RFP-E10+ and GFP-E10-). We focused on critically examining the population of cells producing transcripts with exon 10 (RFP-E10+ isoform), transcripts without exon 10 (GFP-E10- isoform) and cells with transcripts with and without exon 10, an overlap of GFP and RFP forming a yellow false colour (Yellow-E10+/E10-). This essential part of the analysis provides information on the specific set of transcripts modulated by the drugs of interest. It also allows the monitoring of time-dependent splicing events.

The functionality of the PFlare5A-Tau10 mut reporter plasmid and the HCS-Splice assay system has been tested using several splice modulators, and an example of one such modulator has been shown here to reduce exon 10 (E10+) containing transcripts (

Figure 4). The alteration can be envisaged as a therapeutic approach that allows the cells to become similar to their wild-type counterpart. Our data were confirmed by performing co-transfection experiments with a dose-dependent non-targeting siRNA scramble as a control.

5. Conclusions

Overall, our results confirm that the HCS-Splice method, based on the PFlare5A-Tau10 mut, two-colour (GFP/RFP) fluorescent reporter plasmid, can be used to quantify the splicing modulation signal in vitro with greater robustness than existing methods. The integrated HCS-Splice method will have several applications. Firstly, it will broaden the use of two-colour fluorescent reporters to validate putative splicing mutations in human diseases, thereby improving the ability to screen potential splicing-modulating candidates based on nucleic acids, such as ASO or siRNA, able to restore the correct alternative splicing balance. Furthermore, due to the easy miniaturisation of cell culture plate formats, ranging from 96 to 1536 wells, the proposed HCS-Splice method could be applied on a global scale to the screening of both drug and small therapeutic RNA molecule libraries in the context of High Throughput Screening.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Chromatogram sequence; Figure S2: SH-SY5Y cell lines analysis and overall HCS-splice protocol procedure; Figure S3: Exon 10 expression of PFlare5A-Tau10 WT report plasmid after treatment with siRNA-Tau10.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, G.C., A.V., M.A.D., and K.S.; Analysis, G.C., K.S.; Investigation, G.C, K.S., V.A.; Resources, M.A.D., and V.A.; Writing-Original draft preparation, G.C., and K.S.; Writing-review and editing, G.C., V.A., and M.A.D.; Supervision, G.C., V.A, and M.A.D.; Funding acquisition, M.A.D.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Telethon Italy Grant (Project GGP08244), by Department CIBIO, University of Trento (Grant number 40201033) to M.A.D. G.C. received support from the COST Actions-BM1207 Networking toward the clinical application of antisense-mediated exon skipping and by COST Action CA17103 Delivery of Antisense RNA Therapeutics (DARTER) for a short-term scientific mission.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The primary data for this study are available from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Peter Stoilov for kindly providing the dual-Fluorescent MAPT Exon 10 plasmids and Dr Pamela Gatto and Dr Michael Pancher from the High Throughput Screening Core Facility (HTS), Department CIBIO, University of Trento, for the helpful suggestions regarding the acquisitions in High Content Strategy.

Conflicts of Interest

A.V. has declared that no competing financial interests exist. M.A.D, K.S., and G.C are co-inventors of patent WO2016/151523 (RNA interference-mediated therapy for neurodegenerative diseases) filed by the University of Trento and are entitled to a share of royalties. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- Pan, Q.; Shai, O.; Lee, L.J.; Frey, B.J.; Blencowe, B.J. Deep Surveying of Alternative Splicing Complexity in the Human Transcriptome by High-Throughput Sequencing. Nature Genetics 2008, 40, 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.T.; Sandberg, R.; Luo, S.; Khrebtukova, I.; Zhang, L.; Mayr, C.; Kingsmore, S.F.; Schroth, G.P.; Burge, C.B. Alternative Isoform Regulation in Human Tissue Transcriptomes. Nature 2008, 456, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Bush, S.J.; Tovar-Corona, J.M.; Castillo-Morales, A.; Urrutia, A.O. Correcting for Differential Transcript Coverage Reveals a Strong Relationship between Alternative Splicing and Organism Complexity. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2014, 31, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graveley, B.R. Alternative Splicing: Increasing Diversity in the Proteomic World. Trends in Genetics 2001, 17, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsen, T.W.; Graveley, B.R. Expansion of the Eukaryotic Proteome by Alternative Splicing. Nature 2010, 463, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, M.J.A.; Gait, M.J.; Yin, H. RNA-Targeted Splice-Correction Therapy for Neuromuscular Disease. Brain 2010, 133, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Contreras, R.; Cloutier, P.; Shkreta, L.; Fisette, J.F.; Revil, T.; Chabot, B. HnRNP Proteins and Splicing Control. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2007, 623, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Fu, X.D. Regulation of Splicing by SR Proteins and SR Protein-Specific Kinases. Chromosoma 2013, 122, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Manley, J.L. Mechanisms of Alternative Splicing Regulation: Insights from Molecular and Genomics Approaches. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2009, 10, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Rio, D.C. Mechanisms and Regulation of Alternative Pre-MRNA Splicing. Annual Review of Biochemistry 2015, 84, 291–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buratti, E.; Baralle, F.E.; Andreadis, A.; Buratti, E.; Baralle, F.E.; Chen, L.L.; Bush, S.J.; Tovar-Corona, J.M.; Castillo-Morales, A.; Urrutia, A.O.; et al. Influence of RNA Secondary Structure on the Pre-MRNA Splicing Process. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2004, 24, 10505–10514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McManus, C.J.; Graveley, B.R. RNA Structure and the Mechanisms of Alternative Splicing. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development 2011, 21, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandya-Jones, A.; Black, D.L. Co-Transcriptional Splicing of Constitutive and Alternative Exons. Rna 2009, 15, 1896–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.; Oberdoerffer, S. Co-Transcriptional Regulation of Alternative Pre-MRNA Splicing. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 2012, 1819, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlin, A.J.; Clark, F.; Smith, C.W.J. Understanding Alternative Splicing: Towards a Cellular Code. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2005, 6, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.D.; Janitz, M. Alternative Splicing of MRNA in the Molecular Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurobiology of Aging 2012, 33, 1012.e11–1012.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, C.T.; Schofield, P.R.; Turner, A.M.; Kwok, J.B.J. Genetics of Dementia. The Lancet 2014, 383, 828–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewska, D.A.; Lonergan, R.; Fallon, E.M.; Lynch, T. Genetics of Frontotemporal Dementia. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenberg, G.D.; Montine, T.J. The Genetics and Neuropathology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Acta Neuropathologica 2012, 124, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zempel, H.; Mandelkow, E. Lost after Translation: Missorting of Tau Protein and Consequences for Alzheimer Disease. Trends in Neurosciences 2014, 37, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, I.; Schellenberg, G.D. Regulation of Tau Isoform Expression and Dementia. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease 2005, 1739, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Yu, Q.; Zou, T. Alternative Splicing of Exon 10 in the Tau Gene as a Target for Treatment of Tauopathies. BMC Neuroscience 2008, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreadis, A. Tau Splicing and the Intricacies of Dementia. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2012, 227, 1220–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Murrell, J.R.; Goedert, M.; Farlow, M.R.; Klug, A.; Ghetti, B. Mutation in the Tau Gene in Familial Multiple System Tauopathy with Presenile Dementia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1998, 95, 7737–7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedert, M.; Spillantini, M.G.; Crowther, R.A.; Chen, S.G.; Parchi, P.; Tabaton, M.; Lanska, D.J.; Markesbery, W.R.; Wilhelmsen, K.C.; Dickson, D.W.; et al. Tau Gene Mutation in Familial Progressive Subcortical Gliosis. Nature Medicine 1999, 5, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenson, P.D.; Ball, E. V.; Mort, M.; Phillips, A.D.; Shiel, J.A.; Thomas, N.S.T.; Abeysinghe, S.; Krawczak, M.; Cooper, D.N. Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD®): 2003 Update. Human Mutation 2003, 21, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.; Kuo, D.; He, R.; Zhou, J.; Wu, J.Y. Tau Alternative Splicing and Frontotemporal Dementia. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 2005, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefti, M.M.; Farrell, K.; Kim, S.H.; Bowles, K.R.; Fowkes, M.E.; Raj, T.; Crary, J.F. High-Resolution Temporal and Regional Mapping of MAPT Expression and Splicing in Human Brain Development. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froelich, S.; Houlden, H.; Pickering-Brown, S.; Chakraverty, S.; Isaacs, A.; Grover, A.; Hackett, J.; Adamson, J.; Lincoln, S.; Dickson, D.; et al. Association of Missense and 5’-Splice-Site Mutations in Tau with the Inherited Dementia FTDP-17. Nature 1998, 393, 702–705. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, I.; Poorkaj, P.; Hong, M.; Nochlin, D.; Lee, V.M.Y.; Bird, T.D.; Schellenberg, G.D. Missense and Silent Tau Gene Mutations Cause Frontotemporal Dementia with Parkinsonism-Chromosome 17 Type, by Affecting Multiple Alternative RNA Splicing Regulatory Elements. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1999, 96, 5598–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Cote, J.; Kwon, J.M.; Goate, A.M.; Wu, J.Y. Aberrant Splicing of Tau Pre-MRNA Caused by Intronic Mutations Associated with the Inherited Dementia Frontotemporal Dementia with Parkinsonism Linked to Chromosome 17. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2000, 20, 4036–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Yang, L.; Ong, A.A.L.; Shi, J.; Zhong, Z.; Lye, M.L.; Liu, S.; Lisowiec-Wachnicka, J.; Kierzek, R.; Roca, X.; et al. A Disease-Causing Intronic Point Mutation C19G Alters Tau Exon 10 Splicing via RNA Secondary Structure Rearrangement. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levinson, N.; Hinman, R.; Patil, A.; Stephenson, C.R.J.; Werner, S.; Woo, G.H.C.; Xiao, J.; Wipf, P.; Lynch, K.W. Use of Transcriptional Synergy to Augment Sensitivity of a Splicing Reporter Assay. Rna 2006, 12, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soret, J.; Bakkour, N.; Maire, S.; Durand, S.; Zekri, L.; Gabut, M.; Fic, W.; Divita, G.; Rivalle, C.; Dauzonne, D.; et al. Selective Modification of Alternative Splicing by Indole Derivatives That Target Serine-Arginine-Rich Protein Splicing Factors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005, 102, 8764–8769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.L.; Lorson, C.L.; Androphy, E.J.; Zhou, J. An in Vivo Reporter System for Measuring Increased Inclusion of Exon 7 in SMN2 MRNA: Potential Therapy of SMA. Gene Therapy 2001, 8, 1532–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva, K.; Covello, G.; Denti, M.A. Exon-Skipping Antisense Oligonucleotides to Correct Missplicing in Neurogenetic Diseases. Nucleic Acid Therapeutics 2014, 24, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroyanagi, H.; Ohno, G.; Sakane, H.; Maruoka, H.; Hagiwara, M. Visualization and Genetic Analysis of Alternative Splicing Regulation in Vivo Using Fluorescence Reporters in Transgenic Caenorhabditis Elegans. Nature Protocols 2010, 5, 1495–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.; Havlioglu, N.; Tarn, W.Y.; Wu, J.Y. RBM4 Interacts with an Intronic Element and Stimulates Tau Exon 10 Inclusion. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, L.; Covello, G.; Caciotti, A.; Guerrini, R.; Denti, M.A.; Morrone, A. Double-Target Antisense U1snRNAs Correct Mis-Splicing Due to c.639+861C>T and c.639+919G>A GLA Deep Intronic Mutations. Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids 2016, 5, e380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covello, G.; Casarosa, S.; Denti, M.A. Exon Skipping Through Chimeric Antisense U1 SnRNAs. 2022, 00, 1–17.

- Newman, E.A.; Muh, S.J.; Hovhannisyan, R.H.; Warzecha, C.C.; Jones, R.B.; Mckeehan, W.L.; Carstens, R.P. Identification of RNA-Binding Proteins That Regulate FGFR2 Splicing through the Use of Sensitive and Specific Dual Color Fluorescence Minigene Assays. Rna 2006, 12, 1129–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orengo, J.P.; Bundman, D.; Cooper, T.A. A Bichromatic Fluorescent Reporter for Cell-Based Screens of Alternative Splicing. Nucleic Acids Research 2006, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoilov, P.; Lin, C.H.; Damoiseaux, R.; Nikolic, J.; Black, D.L. A High-Throughput Screening Strategy Identifies Cardiotonic Steroids as Alternative Splicing Modulators. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2008, 105, 11218–11223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, D.L.; Data, R.U.S.A. (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0233685 A1. 2010, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Damoiseaux, R.; Chen, L.; Black, D.L. A Broadly Applicable High-Throughput Screening Strategy Identifies New Regulators of Dlg4 (Psd-95) Alternative Splicing. Genome Research 2013, 23, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S. A Cell-Based High-Throughput Method for Identifying Modulators of Alternative Splicing. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press Inc., 2017; Vol. 1648, pp. 221–233.

- Delisle, M.B.; Murrell, J.R.; Richardson, R.; Trofatter, J.A.; Rascol, O.; Soulages, X.; Mohr, M.; Calvas, P.; Ghetti, B. A Mutation at Codon 279 (N279K) in Exon 10 of the Tau Gene Causes a Tauopathy with Dementia and Supranuclear Palsy. Acta Neuropathologica 1999, 98, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Chung, T.D.Y.; Oldenburg, K.R. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. Journal of Biomolecular Screening 1999, 4, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wszolek, K.; F Pfeiffer, V.R.; Bhatt, M.H.; Schelper, R.L.; Cordes, M.M.; Snow, B.J.; Rodnitzky, R.L.; Ch Wolters, E.; Arwert, F.; Calne, D.B. 1992.

- Cheshire, W.P.; Tsuboi, Y.; Wszolek, Z.K. Physiologic Assessment of Autonomic Dysfunction in Pallidopontonigral Degeneration with N279K Mutation in the Tau Gene on Chromosome 17. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical 2002, 102, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yu, Q.; Zou, T. Alternative Splicing of Exon 10 in the Tau Gene as a Target for Treatment of Tauopathies. BMC Neuroscience 2008, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedert, M.; Spillantini, M.G. Tau Mutations in Frontotemporal Dementia FTDP-17 and Their Relevance for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease 2000, 1502, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Carpenter, A.E.; Genovesio, A. Increasing the Content of High-Content Screening: An Overview. Journal of Biomolecular Screening 2014, 19, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketteler, R.; Freeman, J.; Ferraro, F.; Bata, N.; Cutler, D.F.; Kriston-Vizi, J.; Stevenson, N.; Ferraro, F.; Bata, N.; Cutler, D.F.; et al. Corrigendum: Image-Based SiRNA Screen to Identify Kinases Regulating Weibel-Palade Body Size Control Using Electroporation. Scientific data 2017, 4, 170086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vianello, C.; Dal Bello, F.; Shin, S.H.; Schiavon, S.; Bean, C.; Magalhães Rebelo, A.P.; Knedlík, T.; Esfahani, E.N.; Costiniti, V.; Lacruz, R.S.; et al. High-Throughput Microscopy Analysis of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in 2D and 3D Models. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaildrat, P.; Killian, A.; Martins, A.; Tournier, I.; Frébourg, T.; Tosi, M. Use of Splicing Reporter Minigene Assay to Evaluate the Effect on Splicing of Unclassified Genetic Variants. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2010, 653, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, A.; Fushimi, K.; Zhou, X.; Ray, P.; Shi, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S.; Wu, J.Y. RNA Helicase P68 (DDX5) Regulates Tau Exon 10 Splicing by Modulating a Stem-Loop Structure at the 5’ Splice Site. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2011, 31, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheshire, W.P.; Tsuboi, Y.; Wszolek, Z.K. Physiologic Assessment of Autonomic Dysfunction in Pallidopontonigral Degeneration with N279K Mutation in the Tau Gene on Chromosome 17. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical 2002, 102, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuboi, Y.; Uitti, R.J.; Delisle, M.B.; Ferreira, J.J.; Brefel-Courbon, C.; Rascol, O.; Ghetti, B.; Murrell, J.R.; Hutton, M.; Baker, M.; et al. Clinical Features and Disease Haplotypes of Individuals with the N279K Tau Gene Mutation: A Comparison of the Pallidopontonigral Degeneration Kindred and a French Family. Archives of Neurology 2002, 59, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliveri, P.; Rossi, G.; Monza, D.; Tagliavini, F.; Piacentini, S.; Albanese, A.; Bugiani, O.; Girotti, F. A Case of Dementia Parkinsonism Resembling Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Due to Mutation in the Tau Protein Gene. Archives of Neurology 2003, 60, 1454–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goedert, M.; Spillantini, M.G. Tau Mutations in Frontotemporal Dementia FTDP-17 and Their Relevance for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease 2000, 1502, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).