1. Introduction

Quality improvement strategies in childbirth aim to improve and ensure safety during perinatal care [

1]. There is, however, growing evidence that labor has become a medical phenomenon without a clear cause in recent decades [2-7]. Worldwide, the cesarean section (CS) rate has steadily increased from 6.7% in 1990 to 21.1% in 2018 and is expected to rise to 28.5% by 2030 [

8,

9]. In 2015, the World Health Organization proposed the adoption of a universal CS classification system as a global standard for monitoring, evaluating, and comparing delivery rates within a health facility and/or among them [

10]. The Robson classification divides pregnant women into one of 10 mutually exclusive groups based on 5 obstetric characteristics: parity, gestational age, onset of labor, number of fetuses, and fetal presentation [

11]. It is worth noting that the underlying reasons for the increasing trend of CS is important to be evaluated in the light of the multidimensional nature of this phenomenon [

12,

13].

The decision to have a CS is influenced by both clinical and non-clinical factors [

14]. Rates are closely linked to factors that affect women’s risk profile, medical indications, and non-medical reasons including economic, cultural, and social factors[15-18]. For instance, a non-clinical reason that could affect the decision on delivery type is the day and time of delivery. Both human and nonhuman primates share a maternal circadian mechanism that regulates birth patterns[

19]. Based on previous studies [20-22], there is a general consensus that women go into labor mainly at night without any medical interference. In modern populations, cultural factors may have influenced natural adaptation. It is possible that these cultural factors may result in adaptive behaviors that contribute to mother-child viability and health, or they may result in maladaptive behaviors if our genes’ limit of phenotypic plasticity is exceeded [

23]. Due to the unpredictability of vaginal delivery, there is a higher likelihood of unwarranted CS, as it is the only mode of delivery in which the time can be planned [2-4].

Earlier studies have shown inconsistent results regarding non-clinical factors in relation to CS, highlighting the need for further investigation [

24,

25]. The purpose of the current study is to use the Robson classification system to investigate how, independently of medical factors, the day of the week and time of delivery may affect the mode of delivery. The discovery of possible correlations may lead to the development of interventions aimed at reducing unnecessary cesarean sections caused by non-clinical factors.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study is part of a wider research protocol on the implementation of the Robson classification in the Greek setting classification. The methods of the research study have been previously published and are summarized here as follows. This is a single-center retrospective study conducted between January and December 2019. The analysis is based on 7,849 deliveries performed in a tertiary private hospital located in Athens, Greece This hospital is a referral one, and is estimated that it conducts approximately 10,000 deliveries every year. Specifically in 2019, 8,681 deliveries were performed. Women with stillbirth fetuses (n=73) were excluded from the sample.

Data collection was made from the medical records of women who had given birth from 22 weeks of gestation onward and with a neonate weighing at least 500 grams. Data related to the day and time of delivery were retrieved from the electronic health record of women. Anonymity and de-identification were implemented before analysis. Written informed consent was not a prerequisite as all women sign a GDPR form at hospital admission. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital ((protocol code: 1146/24-09/20).

Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as frequencies (n) and percentages (%) for categorical variables. The percent of CS between hourly distributions of deliveries without intervention and with medical intervention (included CS ) was compared using the Chi-squared test. To adjust for potential confounders, a multifactorial logistic regression analysis was carried out to evaluate the contribution of the hourly birth pattern on the cesarean delivery, including all potential confounders of clinical and demographic variables. The statistical analyses were conducted using IBM®SPSS® software, version 22.0 (IBM Corporation). All analyses were two-tailed and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

In our study, medical records and delivery data were collected from 8,572 women. Maternal, newborn, and delivery characteristics are presented in

Table 1. The majority of women were aged between 30 and 39 years old (71,0%) and were of Greek ethnicity (94.6%). A high percentage of the studied population (47,1%) gave birth between 37+0 and 38+6 weeks of gestation and the 39,3% between 39+0 and 41+6. Pregnancy was singleton in 95,6% of the sample and 57,6% of women were nulliparous. Among all deliveries, 60,9% of the sample had a cesarean section, 30,6% had a vaginal delivery and 8,5% had an operative vaginal delivery (vacuum or/and forceps extraction). Regarding the newborns, 51,4% were males and most of them had a birth weight between 3000 and 3999 grams (60,3%).

In

Table 2 is demonstrated the Robson classification per mode of delivery. The four groups that accumulate the highest percentages amongst the total sample according to Robson classification are seen sequentially in group 2, group 5, group 4, and group 1. More specifically, groups 2a+2b comprise the 34.5% (2956/8572) of the sample, groups 5.1+5.2 comprise the 19.8% (1702/8572) of the sample, groups 4a+4b account for the 12.0% (1036/8572) and group 1 accounts for the 10.8% of the study population (928/8572). In group 1 of the Robson classification (nulliparous women with a single cephalic pregnancy, ≥37 weeks gestation in spontaneous labor), 42% of the women gave birth by vaginal delivery, 38.7%by cesarean section and 19.3% by operative vaginal delivery. Considering group 2a of the Robson classification (nulliparous women with a single cephalic pregnancy, ≥37 weeks gestation who had labor induced) we observe a vaginal delivery in 46.4% of the women, a cesarean section in 32.7% of the women and an operative vaginal delivery in 20.9% of the women. As for group 5.1 (all multiparous women with one previous CS, with a single cephalic pregnancy, ≥37 weeks gestation), the vast majority of women (93.3%) gave birth by a cesarean section whereas only 4.0% delivered vaginally and 2.7% via operative vaginal delivery. Women with multiple gestation that fall under group 8 gave birth by vaginal delivery at a rate of 1.8%, by operative vaginal delivery at a rate of 1.3%, while the majority of these women gave birth by a cesarean section at a rate of 96.8%. At last, group 10 which includes all women with a single cephalic pregnancy <37 weeks gestation (including women with previous CSs) the percentage of cesarean sections goes as high as 79.1%.

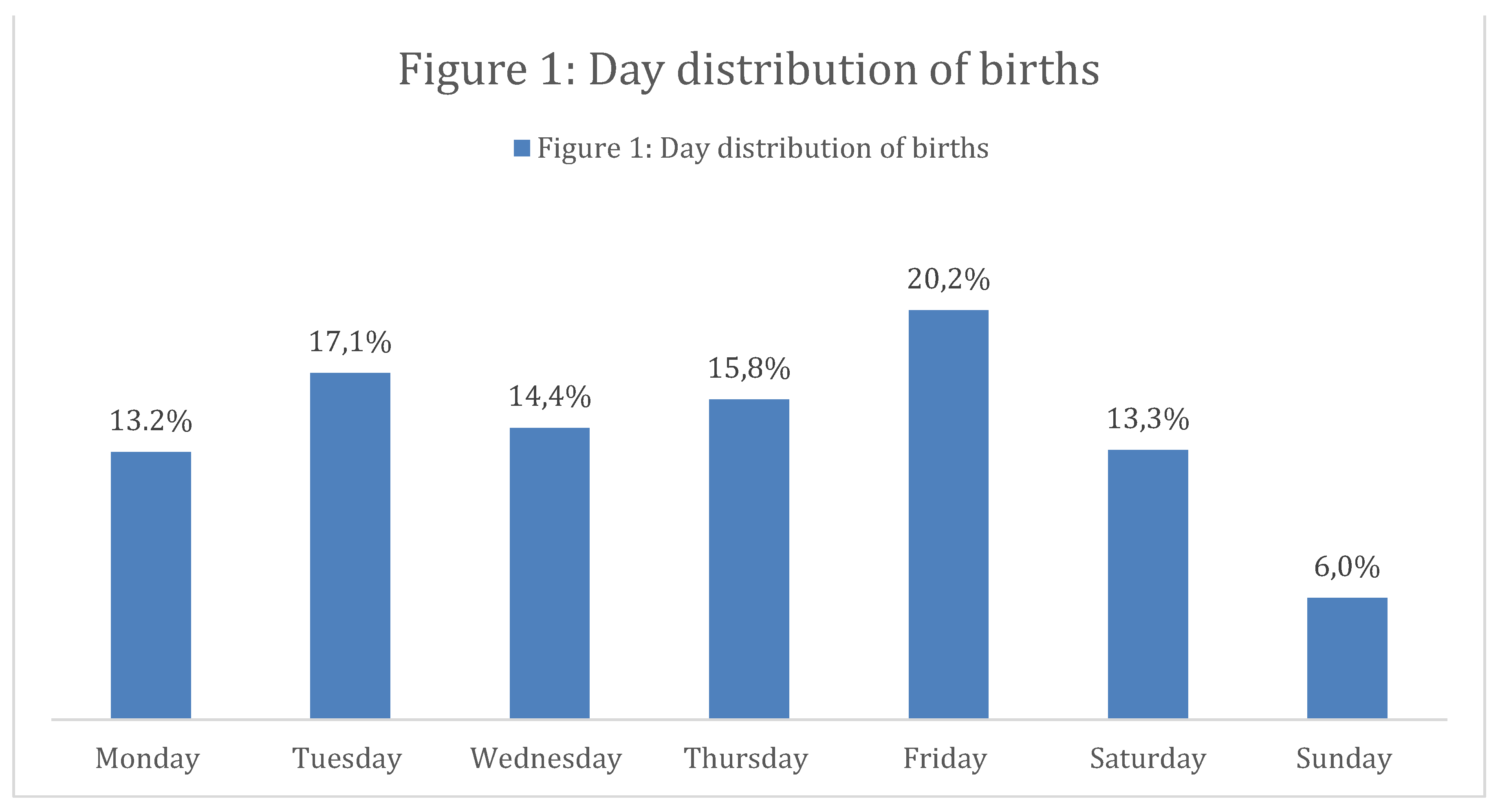

Furthermore, it was detected that 60.5% of all births occur from Monday to Thursday. Higher percentages were observed on Friday (1585/7849) and Tuesday (1340/7849) while lower percentages were noted on Saturday (1046/7849), Sunday (471/7849) and Monday (1035/7849). An amount of 1128 and 1244 women out of 7849 gave birth on Wednesday and Thursday, respectively (

Figure 1). In addition, the distribution of the day by group of the Robson classification shows that in all groups (with the exception of group 3) Sunday is the day with the lowest birth rates (

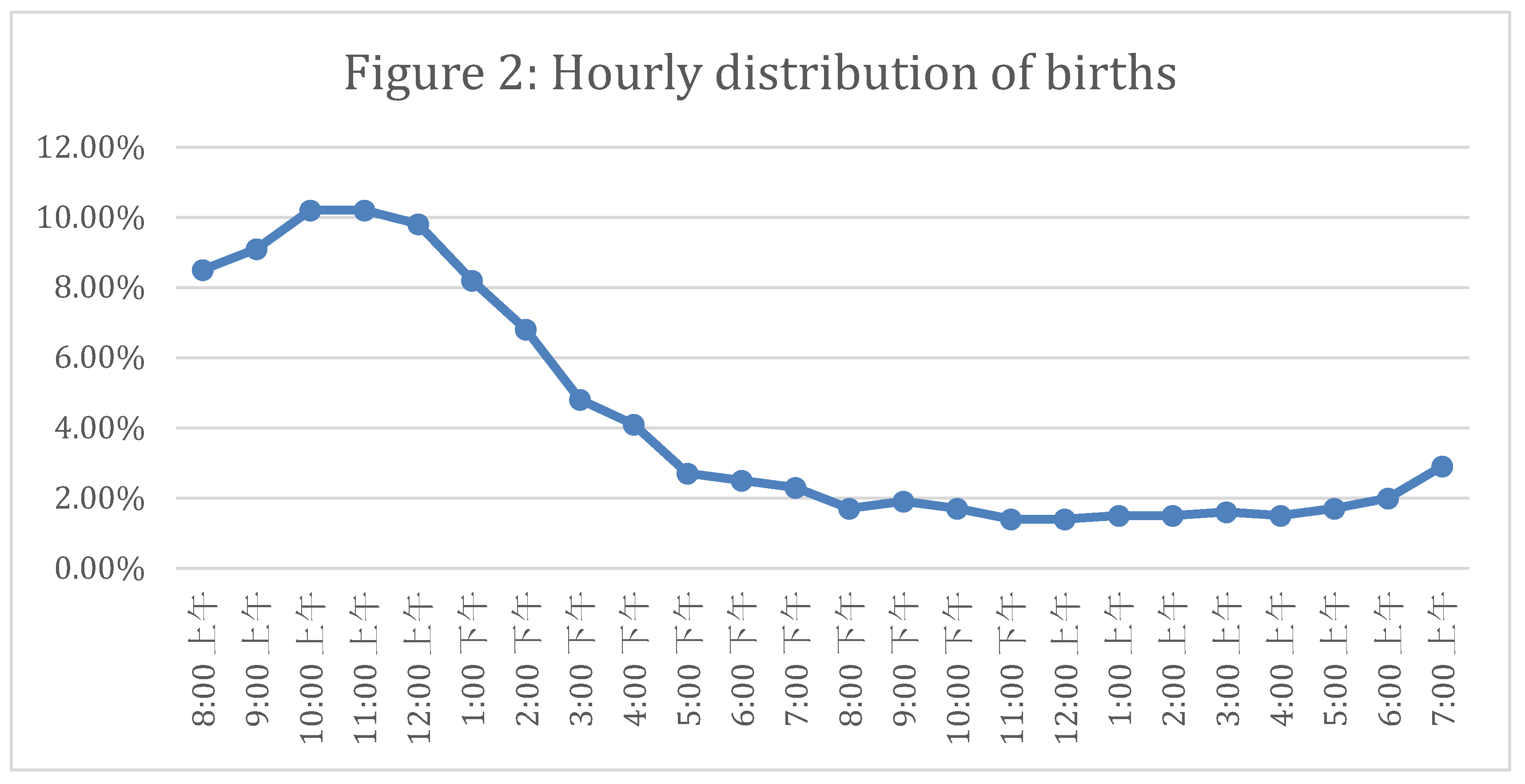

Table 3). Finally, 79,3% of all modes of deliveries took place during the daytime (08:00 a.m.– 07:55 p.m.) with peaks in the morning/daylight hours and decreasing rates in the evening and night (

Figure 2).

In this study, we examined additionally whether the mode of delivery between two types, vaginal delivery (including operative vaginal delivery and VBAC) and cesarean section, is related to time periods (

Table 4). Indeed, a significant difference in the percentage of cesarean sections was observed among the explored time periods (p<0.005). Comparisons by pairs show the divergence between time periods: 08:00 A.M. – 03:59 P.M. compared to 12:00 A.M. – 07:59 A.M. (p<0.005, p

bonferroni<0.005) and 04:00 P.M. – 11:59 P.M. (p<0.005, p

bonferroni< 0.005). Also, between 12:00 A.M. – 07:59 A.M. and 04:00 P.M. – 11:59 P.M. (p<0.005, p

bonferroni< 0.005).

The current analysis revealed a significant difference between time period and Robson classification (Table 5 and

Table 6). More specifically, the current analysis revealed a significant difference between time period 12:00 A.M. – 07:59 A.M. and 08:00 A.M. – 03:59 P.M. [adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.76 (1.22-2.54), p<0.005] and between time period 12:00 A.M. – 07:59 A.M. and 04:00 P.M. – 11:59 P.M. [adjusted OR (95%CI): 2.35 (1.57-3.53), p<0.005] of likelihood of cesarean delivery for Robson group 1. By applying logistic regression analysis models for Robson 1, it becomes apparent that labors performed in the period 08:00 A.M. – 03:59 P.M. are 73% more likely to be carried out through a cesarean section compared to those performed between 12:00 A.M. – 07:59 A.M., and labors performed within the time period 04:00 P.M. – 11:59 P.M. are 2,2 times more likely to be carried out through a cesarean section compared to those performed between 12:00 A.M. – 07:59 A.M.

Similarly for group 2a, labors performed between 08:00 A.M. – 03:59 P.M. are 2.2 times more likely to be carried out via a cesarean section compared to those performed in the interval 12:00 A.M. – 07:59 A.M. whereas labors performed between 04:00 P.M. – 11:59 P.M. are 3 times more likely to be carried out via cesarean section compared to those performed in the interval 12:00 A.M. – 07:59 A.M.

Regarding Robson 5.1, a substantial finding was that labors performed between 08:00 A.M. – 03:59 P.M. were 16.7 times more likely to be carried out through cesarean section compared to those performed in the interval 12:00 A.M. – 07:59 A.M. Lastly, in Robson 10, labors performed in the time period 08:00 A.M. – 03:59 P.M. were 4 times more likely to be carried out through cesarean section compared to those performed in the interval 12:00 A.M. – 07:59 A.M.

4. Discussion

In this retrospective study we demonstrated that over 60% of deliveries during the study period were performed by a cesarean section and 8.5% of deliveries were performed by operative vaginal delivery. It was observed that groups 2 and 5 of the Robson classification are linked to higher cesarean section rates. Based on international literature and WHO recommendations, these percentages are particularly high [

13].

Our earlier study showed that cephalopelvic disproportion and previous cesarean section are the most frequent indications for a cesarean section [

26]. Several studies have associated high cesarean section rates with non-clinical factors. For example, the type of hospital [

27], the age and gender of the doctor [

24], and economic factors [

28] have been correlated with an increased probability of performing CS. In the present study, we sought to examine non-clinical factors related to high cesarean section rates, such as the day and time of delivery. The impact of the day on the delivery mode has not been extensively explored in previous studies. The results of this study indicate that the lowest birth rates are observed on Monday, Saturday, and Sunday. The analysis through the Robson classification allowed us to understand the distribution of births by day for each group separately. The low rates of Sunday deliveries for all Robson groups in our study sample could be attributed to the particularly high rates of “scheduled” deliveries. For instance, groups 5.1 to 9 show cesarean rates more than 90%. Moreover, group 1 appears to have an equal distribution of births during the week. This is probably due to the fact that women in this category were in spontaneous labor. However, an interesting finding was that out of the nulliparous women with a single cephalic pregnancy, ≥37 weeks of gestation, only 928/3884 were in spontaneous labor (Robson 1), while 1709/3884 and 1247/3884 had induced labor (Robson 2a) and planned cesarean section (Robson 2b), respectively. Likewise, a high rate of labor induction was also observed in multiparous women without a previous scar, with a single cephalic pregnancy, >37 weeks of gestation (1007/1408) with the higher rates being noted from Tuesday to Saturday. Similarly, category 10 of the Robson classification which includes all women with a single, cephalic pregnancy <37 weeks gestation, including women with previous scars, presents a lower number of deliveries on Sunday which reveals the “scheduled” nature of preterm births rather than the state of emergency it should bear.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to present the daily distribution of births by Robson classification. Therefore, there is no previous evidence to compare our data with. In an earlier study conducted in three hospitals (two public and one private) in Greece, it seemed that in the private hospital, there was a rapid decrease in cesarean sections on Sunday while in the two public hospitals, there was a decrease in cesarean sections and an increase in vaginal deliveries on the weekdays [

29]. A recent study in America showed that women who give birth during weekends are 27% less likely to have CS, compared to those who give birth on weekdays [

30]. Furthermore, in our study, the hourly distribution of labor was not stable and shows a de-escalating trend during the 24 hours. Between 12:00 A.M. - 07:59 A.M., only 1101/7849 deliveries were performed, with vaginal delivery rates of 58.5% and cesarean section rates of 41.5%. Our results are not in agreement with previously published data from England [

31] and Austria [

32], showing overnight delivery rates up to 55.8% and 49.2% respectively. Of the total number of vaginal deliveries (N=2625), the minority of them (N=644) were performed between 12:00 A.M. - 07:59 P.M. while the majority of them (N=1328 women) were performed between 08:00 am - 03:59 pm. Besides, our findings are in contrast with the results of previous studies reporting higher rates of vaginal delivery during the night [

31,

32,

33].

Furthermore, our findings do not seem to follow the biological expression of childbirth which is related to the increase in the secretion of melatonin and oxytocin during the night, resulting in higher rates of vaginal delivery during night hours [

34,

35]. In a recent study by Kanwar et al., it is summarized that night deliveries are not only numerically more but appear to be also physiologically more efficient than day-onset deliveries [

33]. In an earlier study conducted in Greece, it was shown that the time of delivery is a significant factor for the increase in cesarean sections with >70% of them being performed between 8:00 A.M. - 4:00 P.M. [

29] Our results align with this finding, indicating that in Greece healthcare policies and obstetrics practices need more effective strategies in labor management. The comparison between time of delivery and mode of delivery raises questions about which groups of women influence this association. The Robson classification gave us a deeper interpretation of our results. While our results, unfortunately, highlight the medicalization of childbirth as women in Robson category 1 are 73% more likely to deliver by cesarean section between 08:00 A.M. - 3:59 P.M. compared to those who give birth between 12:00 A.M. - 07:59 A.M. At last, women in group 5.1 are 16.7 times more likely to deliver by cesarean section in the morning compared to overnight deliveries. This is due to the particularly high rates of repeat cesarean section and the low rates of VBAC in the Greek population as has been supported also by previous studies [

29,

36].

Strength and Limitations

Our work presents some strengths and limitations. First, the sample size of our study was large enough to achieve an annual representative sample of births in Greece that is considered representative of the Greek population hospital that approved this study, is the largest private obstetrical clinic in Greece and consequently, serves as a referral hospital having a full complement of services, including obstetrics, neonatology and intensive care units, strengthening therefore, the representativeness of our sample. Second, it was the first time that non-clinical factors were studied by applying the Robson classification in Greece. We are aware, though, that our research had some limitations as well. The main limitations of our study was its retrospective nature and the fact that it was conducted in a single hospital. Additionally, we could not account for all non-clinical confounders. Unfortunately, we were unable to study the level of urgency for the performed cesarean sections because the available data were of heterogeneous quality which could lead us to misleading conclusions.

5. Conclusions

To conclude, the findings of the present study add significant information on the association of non-clinical variables with increasing the trends of cesarean section in the Greek setting. Robson’s classification appears to be an effective tool for studying, in a standardized manner, non-clinical variables associated with the mode of delivery. Investigation of additional non-clinical variables through qualitative research would be a useful tool for quality improvement in hospitals to ensure the provision of equal and impartial perinatal care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G. and A.L.; methodology, P.G. and A.G.; validation, K.G., V.V., D.M., A.G., and A.L.; investigation, P.G.; resources, P.G. and A.L., data curation, P.G., writing—original draft preparation, P.G., D.M.; writing—review and editing, P.G. and K.G.; visualization, A.L.; supervision, A.L.; project administration, A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval was received by the hospital’s scientific board (1146/24-09-2020).

Informed Consent Statement

It was not required to receive a signed consent form by the patients’ whose medical record were retrieved as these patients had already signed a GDPR form. The data were collected from the digital medical records of the women. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The APCs will be paid by the Special Account for Research Grants, University of West Attica, Athens, Greece.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pettker CM, Grobman WA. Obstetric Safety and Quality. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jul;126(1):196-206. [CrossRef]

- Gibbons L, Belizán J, Lauer J, Betrán A, Merialdi M, Althabe F. The global numbers and costs of additionally needed and unnecessary caesarean sections performed per year: overuse as a barrier to universal coverage. World Heal Rep Backgr Pap 2010;30:1–31.

- Ye J, Betrán AP, Guerrero Vela M, Souza JP, Zhang J. Searching for the optimal rate of medically necessary cesarean delivery. Birth. 2014 Sep;41(3):237-44. [CrossRef]

- Souza JP, Gülmezoglu A, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Carroli G, Fawole B, Ruyan P; WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health Research Group. Caesarean section without medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short-term maternal outcomes: the 2004-2008 WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health. BMC Med. 2010 Nov 10;8:71. [CrossRef]

- Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The Increasing Trend in Caesarean Section Rates: Global, Regional and National Estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS One. 2016 Feb 5;11(2):e0148343. [CrossRef]

- Le Ray C, Blondel B, Prunet C, Khireddine I, Deneux-Tharaux C, Goffinet F. Stabilising the caesarean rate: which target population? BJOG. 2015 Apr;122(5):690-9. [CrossRef]

- Brennan DJ, Murphy M, Robson MS, O’Herlihy C. The singleton, cephalic, nulliparous woman after 36 weeks of gestation: contribution to overall cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Feb;117(2 Pt 1):273-279. [CrossRef]

- Betran AP, Torloni MR, Zhang JJ, Gülmezoglu AM; WHO Working Group on Caesarean Section. WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates. BJOG. 2016 Apr;123(5):667-70. [CrossRef]

- Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Souza JP, Zhang J. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health. 2021 Jun;6(6):e005671. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Human Reproduction Programme, . WHO Statement on caesarean section rates. Reprod Health Matters. 2015 May;23(45):149-50. 10 April. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Robson Classification: Implementation Manual, Geneva. 2017.

- Ye J, Zhang J, Mikolajczyk R, Torloni MR, Gülmezoglu AM, Betran AP. Association between rates of caesarean section and maternal and neonatal mortality in the 21st century: a worldwide population-based ecological study with longitudinal data. BJOG. 2016 Apr;123(5):745-53. [CrossRef]

- Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Souza JP, Zhang J. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health. 2021 Jun;6(6):e005671. [CrossRef]

- Betran AP, Torloni MR, Zhang J, Ye J, Mikolajczyk R, Deneux-Tharaux C, Oladapo OT, Souza JP, Tunçalp Ö, Vogel JP, Gülmezoglu AM. What is the optimal rate of caesarean section at population level? A systematic review of ecologic studies. Reprod Health. 2015 Jun 21;12:57. [CrossRef]

- Mylonas I, Friese K. Indications for and Risks of Elective Cesarean Section. DtschArztebl Int. 2015 Jul 20;112(29-30):489-95. [CrossRef]

- Aminu M, Utz B, Halim A, van den Broek N. Reasons for performing a caesarean section in public hospitals in rural Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014 Apr 5;14:130. [CrossRef]

- Oner C, Catak B, Sütlü S, Kilinç S. Effect of Social Factors on Cesarean Birth in Primiparous Women: A Cross Sectional Study (Social Factors and Cesarean Birth). Iran J Public Health. 2016 Jun;45(6):768-73.

- XL, Xu L, Guo Y, Ronsmans C. Factors influencing rising caesarean section rates in China between 1988 and 2008. Bull World Health Organ. 2012 Jan 1;90(1):30-9, 39A. [CrossRef]

- Bernis C, Varea C. Hour of birth and birth assistance: from a primate to a medicalized pattern? Am J Hum Biol. 2012 Jan-Feb;24(1):14-21. [CrossRef]

- Camargo CC, Ferrari SF. Observations of daytime births in two groups of red-handed howlers (Alouatta belzebul) on an island in the Tucuruí reservoir in eastern Brazilian Amazonia. Am J Primatol. 2007 Oct;69(10):1075-9. [CrossRef]

- Honnebier MB, Nathanielsz PW. Primate parturition and the role of the maternal circadian system. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994 Jun 30;55(3):193-203. [CrossRef]

- Trevathan, WR. 1987. Human birth. An Evolutionary Perspective. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Martin, RD. The evolution of human reproduction: a primatological perspective. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007;Suppl 45:59-84. [CrossRef]

- Burns LR, Geller SE, Wholey DR. The effect of physician factors on the cesarean section decision. Med Care. 1995 Apr;33(4):365-82. [CrossRef]

- Evans MI, Richardson DA, Sholl JS, Johnson BA. Cesarean section. Assessment of the convenience factor. J Reprod Med. 1984 Sep;29(9):670-6.

- Giaxi P, Gourounti K, Vivilaki V, Zdanis P, Galanos A, Antsaklis A, Lykeridou A. Implementation of the Robson Classification in Greece: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 Mar 21;11(6):908. [CrossRef]

- Hoxha I, Syrogiannouli L, Luta X, Tal K, Goodman DC, da Costa BR, Jüni P. Caesarean sections and for-profit status of hospitals: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017 Feb 17;7(2):e013670. [CrossRef]

- Gruber J, Kim J, Mayzlin D. Physician fees and procedure intensity: the case of cesarean delivery. J Health Econ. 1999 Aug;18(4):473-90. [CrossRef]

- Mossialos E, Allin S, Karras K, Davaki K. An investigation of Caesarean sections in three Greek hospitals: the impact of financial incentives and convenience. Eur J Public Health. 2005 Jun;15(3):288-95. [CrossRef]

- Del Carmen GA, Stapleton S, Qadan M, Del Carmen MG, Chang D. Does the Day of the Week Predict a Cesarean Section? A Statewide Analysis. J Surg Res. 2020 Jan;245:288-294. [CrossRef]

- Knight HE, van der Meulen JH, Gurol-Urganci I, Smith GC, Kiran A, Thornton S, Richmond D, Cameron A, Cromwell DA. Birth "Out-of-Hours": An Evaluation of Obstetric Practice and Outcome According to the Presence of Senior Obstetricians on the Labour Ward. PLoS Med. 2016 Apr 19;13(4):e1002000. [CrossRef]

- Windsperger K, Kiss H, Oberaigner W, Leitner H, Muin DA, Husslein PW, Farr A. Working-hour phenomenon in obstetrics is an attainable target to improve neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Sep;221(3):257.e1-257.e9. [CrossRef]

- Kanwar S, Rabindran R, Lindow SW. Delivery outcomes after day and night onset of labour. J Perinat Med. 2015 Nov;43(6):729-33. [CrossRef]

- Schulz P, Steimer T. Neurobiology of circadian systems. CNS Drugs. 2009;23 Suppl 2:3-13. [CrossRef]

- Lindow SW, Newham A, Hendricks MS, Thompson JW, van der Spuy ZM. The 24-hour rhythm of oxytocin and beta-endorphin secretion in human pregnancy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1996 Oct;45(4):443-6. [CrossRef]

- Charitou A, Charos D, Vamenou I, Vivilaki VG. Maternal and neonatal outcomes for women giving birth after previous cesarean. Eur J Midwifery. 2019 Apr 17;3:8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).