Introduction

The function of schools is to enhance teaching efficiency to improve student learning outcomes while meeting the evolving needs of society (OECD, 2011, 2022; Seals et al., 2017). By introducing innovation in teaching and learning, schools can improve student outcomes leading to better-prepared graduates while positively impacting society (Hayat et al., 2015). Nonetheless, spurring innovation requires adequate funding, which is often lacking in weighted student funding (WSF). In most countries, schools primarily rely on their WSF to maintain school operations and promote innovations, while generally being required to use all allocated funds within the school year (Roza, Hagan & Anderson, 2021). Despite significant financial investments by governments, the WSF is often insufficient. High staffing costs burden schools as they must maintain a certain teacher-to-student ratio, leaving little money from the WSF for small initiatives (Baumol, 2012). Over the past two decades, there has been a growing recognition of the important role played by school principals for ensuring the effective use of the WSF (Bush & Oduro, 2006; Palardy, 2008). Despite this emphasis, few studies, if any, have explored the efficacy of specific strategies employed by principals to leverage the WSF to benefit school operations and increase innovation (Bush, 2018; Currie, Boyett & Suhomlinova, 2005; Mette & Scribner, 2014).

The primary objective of the present study is to provide new insights into how a principal enabled successful school operations and spurred innovation, specifically through the efficient management of the school’s WSF. Accordingly, the study is guided by three research questions: 1) What is the principal’s perception of utilizing the school’s WSF? 2) What strategies does the principal employ to manage the WSF for maintaining school operations and promoting innovation? (Notably, school financial decision-making is often a collaborative effort involving various stakeholders, including principals and teachers [Shen & Yang, 2022]). Therefore, a third question was devised: 3) How do teachers react to a principal’s strategies in managing the school’s WSF?

Literature review

Weighted student funding (WSF)

WSF is a school funding model that allocates funding based on the individual needs of each student. A fixed amount of money from the government is allocated for each student, with additional funds for those requiring extra support, including students with special needs, second language learners, or those from low-income families (Roza et al., 2021). All unspent school funds are returned to the government treasury (call-back), although most schools tend to use the funds carefully at the beginning of the year and spend any remaining money at the end of the year (Grubb, 2006). The WSF system is prevalent in countries with decentralized education systems, such as the United States and the Netherlands, which grant schools more autonomy (Ladd & Fiske, 2011; Tuchman, Gross & Chu, 2022). Although the WSF mechanism can vary depending on the country, a shared objective of allocating financing based on student need is typically employed (Jarmolowski, Aldeman & Roza, 2022; Ladd & Fiske, 2011).

The two most common uses of the WSF are to maintain school operations and promote innovation. Schools utilize their WSF to distribute resources across various day-to-day operations, including but not limited to staff salaries, materials, technology, professional development, and other programs and services (Baumol, 2012; Chambers, Levin & Shambaugh, 2010). Schools also use their WSF to encourage innovation and enhance their teaching and learning approaches in response to the evolving educational environment (Ho & Bryant, 2021; Ladd & Fiske, 2011). However, for schools to successfully facilitate innovative teaching and learning practices, additional funding beyond the WSF must be sought for teacher training, staff relief, and upgrading facilities, among others (Ladd & Fiske, 2011). Thus, to secure funding for innovative practices, schools often submit proposals to donors or government agencies that are aligned with the nature of the innovation (Follows, 2003; Ho et al., 2021). This type of funding, however, lacks flexibility, particularly when it comes to the granularity of each expenditure, which often forces schools to craft initiatives that match the criteria and preferences set by the funding source, rather than the needs of their students (Follows, 2003). Given the constraints of securing extra funding, schools must monitor their budgets effectively to support and sustain teaching and learning initiatives (Rahayu, Ludigdo & Irianto, 2015).

WSF mechanism within schools

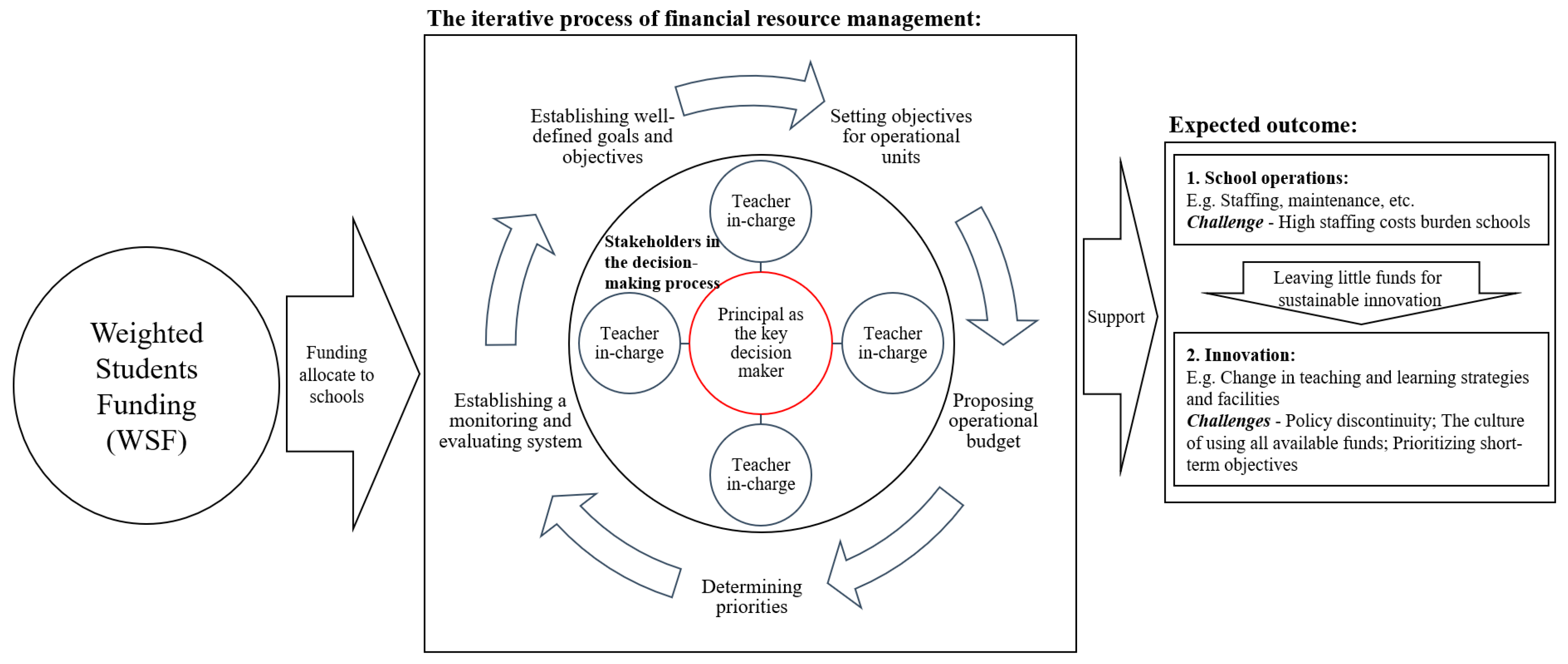

In reviews of the literature on financial resource management, McKinney (2004) and Yizengaw and Agegnehu (2021) suggest that managing financial resource mechanisms in schools involves five iterative steps that school principals should use to sustain innovations that align with their goals.

First, budget preparation requires the establishment of well-defined goals and desired outcomes, particularly concerning advocating initiatives (McKinney, 2004). To achieve this, goals must be identified and provided the necessary funding to attain them, leading to a long-term investment plan for deploying resources. School leaders should allocate funding according to their needs, aligning with their overall desired outcomes (Barbour et al., 2011; Clune, 1994).

Second, setting objectives for operational units is an essential component of budget preparation (McKinney, 2004). Within this process, each department and working committee should identify specific goals that align with the school’s overall objectives (Yizengaw and Agegnehu, 2021). The responsibility of establishing these objectives is typically given to unit leaders who play a critical role in ensuring that each department contributes towards achieving the school’s desired outcomes (Follows, 2003).

Third, proposing operational budgets involves the translation of goals and objectives into implementation plans by operational units. These plans are then used to justify financial resource allocation (Barbour et al., 2011; Yizengaw and Agegnehu, 2021). Within a proposed budget, each plan should have detailed cost estimates, allowing school leaders to make informed decisions about how to allocate their funds (Barbour et al., 2011; Bruno, 2022).

Fourth, preparing a budget in educational institutions involves determining priorities (McKinney, 2004) wherein school leaders are required to rank budgeted items based on their potential impact on the development of the school and their cost-effectiveness (Bruno, 2022). This necessitates ranking each item based on its ability to achieve the school’s goals and objectives (Yizengaw and Agegnehu, 2021). The organization can allocate more funding towards high-priority items while reducing it for lower-priority ones.

Finally, establishing a monitoring and evaluating system is crucial for making informed decisions based on data (McKinney, 2004). A possible monitoring and evaluating system could include collecting data on attendance rates, analyzing trends and patterns, and using this information to make informed decisions regarding program adjustments or resource allocation (Tuchman et al., 2022). By regularly monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of programs or initiatives, schools can ensure that their limited financial resources are being used effectively to achieve their desired outcomes.

Challenges for WSF

Theoretically, by using these five iterative steps of financial resource management, which are commonly employed globally (Ladd & Fiske, 2011; Tuchman et al., 2022), schools can support initiatives for school improvement. Nevertheless, in practice, there are many impediments to the effective application of WSF hampering school innovation (Jarmolowski et al., 2022; Ladd & Fiske, 2011).

Policy discontinuity

Within the WSF system, potential changes in national policy (Fiske & Ladd, 2010; Ritter & Lauver, 2003) and high staffing costs (Baumol, 2012) may deter long-term planning and investment in innovation. At the national level, educational reform is often subject to fads and short-term trends (Fiske & Ladd, 2010), forcing school leaders to allocate resources to initiatives that are either temporarily popular or have public support (Woods, Bagley, & Glatter, 2005). The lack of a national education policy can also interfere with sustainable school innovation (Ritter & Lauver, 2003). At the school level, the disproportionately high expenditure of WSF funds on staffing costs has hindered the ability to consistently allocate sufficient resources to new initiatives (Baumol, 2012). Insufficient funds thus can reduce a school’s capacity to continue supporting formerly successful initiatives or policies over time, especially as new initiatives emerge (Kim, Reid & Galey, 2022).

The culture of using all available funds

School budgets are often estimated and planned based on projections that may not align with a school’s actual expenses or needs (Mardolkar & Kumaran, 2020). This misalignment can lead to underspending or unutilized resources at the end of an academic year. As the WSF’s claw-back system often motivates schools to spend all available funds before the end of the fiscal year to avoid losing them, schools may spend imprudently without proper planning hindering long-term development (Caplan, 2018; Grubb, 2006).

Prioritizing short-term objectives

Innovation often requires several staff to establish a foundation, e.g., acquiring teaching materials or fostering school-community partnerships (Blumenfeld et al., 2000; Ngobeni, 2022). As funding is limited, schools tend to reward emergent teaching and learning needs that align with departmental and school goals (Caplan, 2018; Grubb, 2006). Thus, they may be left with only small budgets for subject heads to pilot initiatives (Chambers et al., 2010). Insufficient funds for launching initiatives also make it challenging for subject heads to execute long-term projects.

The Principals - the key decision makers of the WSF

School principals are the key decision makers regarding funding allocation; i.e., they decide how to allocate funds and oversee their implementation, ensuring they align with school goals (Mette & Scribner, 2014). They are also accountable and responsible for their decisions (Bush & Oduro, 2006; Palardy, 2008). For example, they provide a supportive environment by funding training, facilities, and teaching resources, which sustains daily operations and fosters innovations (Bush, 2018; Currie et al., 2005; Mette & Scribner, 2014).

Studies have noted that various leadership styles can result in different priorities in financial decision-making. For example, research has shown that instructional school leaders can efficiently deploy financial resources to improve a teacher’s performance (Currie et al., 2005). Similarly, a study on transformational leadership found that transformational school leaders utilize financial resources to support teacher professional development, enabling them to understand new initiatives which cultivates positive feelings among teachers about supporting school improvement efforts (Bush, 2018). Transactional school leaders may use financial resources to provide rewards or incentives to comply with their directives (Mette & Scribner, 2014).

Despite the important role played by principals, financial decision-making not only pertains to devising optimal budgeting strategies but also to managing the stakeholders involved in the process (Bush & Oduro, 2006; Palardy, 2008). For instance, to prioritize innovation, principals need to allocate more funding and establish resource allocation committees; however, any reallocation of funds may cause teacher dissatisfaction and undermine the program’s success (Ho & Bryant, 2020; Lasky, 2005). Teachers may raise concerns about prioritizing initiatives if they feel their self-interests are diminished (Walker, 2012). Thus, schools sometimes must bear the risk of staff morale challenges when sustaining innovative programs (Ho et al., 2020; Lasky, 2005; Walker, 2012; Shen & Yang, 2022).

Drawing insights from existing literature on principal leadership, it is evident that principals play a critical role in leveraging support for innovation. And it is principals who have the power to influence teachers’ perceptions about resource allocation. However, studies have tended to overlook how principals make financial resource decisions; therefore, the complex interplay between principals’ perceptions of WSF and their practices needs further investigation (see

Figure 1).

Figure 1 synthesizes the literature reviewed above as a conceptual framework, leading to the research methodology.

Hong Kong context

The Education Bureau in Hong Kong, the context of the study, has implemented a stringent monitoring system for schools regarding the WSF. This approach is consistent with the five steps for managing a school’s finances as outlined by McKinney (2004) and Yizengaw and Agegnehu (2021). In 2002, educational reform was launched in Hong Kong to promote students’ whole-person development and lifelong learning through a series of structural, curricular, and pedagogical changes (James, 2021). Although every school in Hong Kong can apply for two million Hong Kong dollars (about USD260k) from the government to launch innovations that align with government advocacy, initiatives focused on meeting the specific needs of students or teachers are mostly considered already funded by the WSF. This implies that schools must bear the responsibility of maintaining the sustainability of new projects through using their WSF, which tends to increase their financial burden (Chai, 2019). These challenges highlight the difficulties that Hong Kong principals face in promoting innovation using their WSF. In essence, they must leverage their WSF to achieve their goals while maintaining educational standards and addressing teachers’ concerns regarding resource allocation.

Methodology

The study adopted a case approach to address the research questions and gap in the literature. Case studies can provide an in-depth exploration describing how WSF is used showing the complex interplay between a principal’s strategies and their interactions with teachers, particularly in relation to financial resource management. Such an approach where the interests of multiple stakeholders need to be balanced can best capture the dynamic nature of decision-making (Merriam, 1998).

Sampling

A principal was selected as the study subject using two selection criteria: 1) The principal had to be utilizing the WSF to initiate innovation with a substantial budget and the support of the school; 2) The innovation had to have been sustained for three years or more. These criteria were used to identify a principal who had effectively addressed the challenge of utilizing the WSF to promote sustainable innovation in their school. To facilitate the selection of a suitable candidate, the researcher requested the Hong Kong Principal Association to nominate 10 school principals who fulfilled the selection criteria. The review process involved scrutinizing the schools’ plans and records from 2018 to 2022. Three principals were then identified. Two scholars evaluated their school profiles and innovative practices focusing on school innovation. Then a site visit to the three schools was conducted by the author. Finally, one principal was selected as the most viable subject of the study. The background of the principal’s school and the participant’s demographic information are reported in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Data collection

The study primarily used semi-structured interviews and school documents (curriculums, lesson plans, and students’ work). The author conducted three site visits (240 minutes) to the school to attend meetings and lessons and engage in conversations with students and teachers. The interviews were conducted with six participants in the school, including the school’s principal, two vice-principals, and three teachers responsible for innovations. Before conducting the interviews, the author reviewed the school’s plans and reports to comprehensively understand the background of the initiatives, which helped develop the interview questions. The questions probed about the participants’ general perceptions of using WSF, the school’s goals in the past five years, the overall process of assessing financial resource needs, resource allocation decision making, the ways of configuring and leveraging resources for innovation, and the strategies for innovation sustainability. To ensure the credibility and accuracy of responses, the author conducted interviews with the vice-principals and teachers in charge of initiatives as a form of triangulation (Maxwell, 2013). The author also invited the teachers in charge to share their curriculums, lesson plans, and students’ work to verify the usage of new facilities arising from initiatives. During the site visit, the author served as an observer and took field notes describing the decision-making process in meetings and the learning process in during lessons. The author also wrote memos after each conservation between the author, teachers, and students. In total, four meetings were attended, and three classes were observed.

Data analysis

The study adopted Miles, Huberman and Saldaña’s (2014) interactive data analysis model. The data analysis process involved two stages. Reflective memos were created immediately after conducting interviews and reviewing relevant documents in the first stage. The author then categorized data based on budgeting processes, and data displays were generated to verify the authenticity and validity of data sources. For example, the author constructed a timeline depicting the budgeting process and cross-referenced the interview and document data against it to identify any potentially missing sources of information and to verify the validity of their claims. This provided a holistic picture of the budgeting. To serve as a basis for further data collection, interim summaries for each interviewee were composed. Based on these summaries, data display techniques were used to verify the authenticity of each mentioned event while examining how the interviewees perceived and interpreted the same situation differently. Any doubtful data was rectified by collecting additional data at the research site.

The author coded data into descriptive and interpretive categories in the second stage. Descriptive codes were used for facts, while interpretive codes uncovered participants’ beliefs behind their actions. Participant feedback enhanced the code’s reflexivity (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). The interviews were conducted in Chinese, with all translated quotations being verified by a professional translator from a reputable newspaper company. Additionally, participants were provided the opportunity to confirm the accuracy of the translations themselves. Pattern categories were generated using pattern-matching and concept mapping techniques to indicate the principal’s strategies that enhanced innovation sustainability. Finally, three thematic categories emerged in response to the research questions: (1) the principal’s perceptions of utilizing WSF; (2) the principal’s strategies for leveraging WSF for innovation; and (3) the teachers’ reactions.

Findings

This section presents the main findings regarding the use of WSF over three academic years (2018-2021). The results were categorized according to each academic year delineating three distinct themes for each year. Representative quotes are used to illustrate these themes and highlight the key findings.

Gearing up for school transformation in 2018/19

Theme 1 - Perceptions of utilizing WSF: The need to reduce financial rigidity

The principal recognized the need to move away from the stringent financial management procedures of the WSF to encourage equality and innovation in his school. He acknowledged the importance of financial management procedures; however, he said some procedures were too inflexible and may have hindered creativity. For instance, every extra amount of financial support from the WSF required a clear description of the use of money at the beginning of the year even though the needs of students varied during the year.

“The government’s special funding for new policies, especially for SEN students, is not sustainable in the long term. They may need different experts or equipment to support their learning, and it constantly changes. However, all budgets are fixed at the beginning of the year, most likely spent on hiring teachers.”

Principal

These rigid processes can restrict a school’s ability to adapt to changing student and societal needs, resulting in a lack of innovation. Additionally, the funding formulator of the WSF can disproportionately affect students and schools from low-income backgrounds, exacerbating existing inequalities.

“The current education funding system is unfair and creates inequity. We have many students from low-income families, and the resources we receive aren’t enough to properly care for them. We have to put in triple the effort to provide the support they need with the same resources as other schools.”

Principal

Considering these issues, the principal was committed to promoting equity and innovation by introducing novel and flexible financial management procedures that moved beyond the survival mode cycle. For example, he established a committee to deliberate on the allocation of funds to support students in need.

Theme 2 - Principal strategies: Preparing for student-centered school innovation

The principal actively worked towards creating alignment among stakeholders to support student-centered innovation as the basis for the following year’s changes. First, he evaluated school renovation needs through a student-centered lens. He engaged with each student (n=150) individually to understand their expectations, which enabled him to identify areas needing improvement to enhance student retention. Additionally, he guided the middle leaders in drafting departmental plans, ensuring that teachers understood the reasoning behind changes and the requisite steps involved in implementation. He aimed to train teachers to approach their work more thoughtfully. For example, after the initial draft, the principal met with each department head to discuss their respective plans. Together, they reviewed the plan and clarified every item.

“It’s important for our teachers to clearly understand why they are being asked to do something and the steps involved in implementing it. This helps them to approach their work in a more thoughtful and effective way.”

Principal

“Since joining us, he has diligently reviewed our plans, asking questions and seeking to understand our reasoning. He’s detail-oriented, even checking our grammar to ensure clarity in our writing.”

Teacher A

Later, the principal worked with middle leaders, helping them shape the direction of school innovation. Together, they decided on three key directions for the school: for the future, for teachers’ and students’ well-being, and for the community. With a clear direction, the principal wanted to ensure the teachers knew the significance of the three key directions by continuously emphasizing the importance of student-centered innovation, even in less relevant scenarios.

“He talks about his ideal school in every scenario you can imagine, from staff meetings to informal chats to morning assemblies. It’s clear that he is passionate about our school.”

Teacher B

Furthermore, the principal made a commitment to financial resource conservation. He saved whenever possible and used the remaining funds before the accounting period ended, ensuring the most efficient use of available resources. For instance, he noticed that the career guidance committee had not spent all of its allocated funds. Upon confirmation, the principal promptly sought quotations for coffee machines, which were to be used for the following academic year’s “experiential learning” in the café.

“To prepare for potential fund recalls, I save whenever possible. I’m mindful of my spending, as colleagues often forget their budgets. At year-end, I plan to use the remaining funds effectively before the accounting period ends.”

Principal

Theme 3 - Teachers’ reaction: Recognizing the possibility of imminent change in the school

Teachers at the school were aware of the possibility of significant changes in the school environment, albeit they were uncertain about the details. They acknowledged that they learned the importance of meticulous planning and commitment to consistent improvement, exemplified by their eagerness to revise and enhance their plans multiple times under the principal’s guidance. Nevertheless, certain teachers found it hard to understand the principal’s operational plan even if they agreed with the school development direction leaving them feeling unsure and waiting for more explicit instructions.

“At first, all I knew was his slogan (Three key directions for the school). I agreed with his directions but I didn’t clearly understand what he wanted to do. It felt like waiting for the thunder before the rain.”

Teacher A

Notably, many teachers were initially oblivious to the principal’s efforts to conserve funds and only became aware of it when the plan for constructing a cafe was announced for the upcoming academic year.

“It finally dawned on us that he had saved a lot when he announced plans to build a cafe in the upcoming academic year.”

Vice-principal A

Seeding innovation through resource optimization in 2019/20

Theme 1 - The perception of utilizing WSF: Adversity breeds survival intention

The principal perceived the challenges of limited financial resources facing the school which prompted him to reflect on how to ensure the school’s survival and future success. To initiate innovations within the school, he relied on the WSF as seed funding. This limited funding required him to consider the most effective use of resources.

“I only have a small saving from the WSF, so I need to use it effectively to make some changes. At least, … If you can’t succeed, you should aim for a noble failure.”

Principal

The principal also understood that he had to seek creative ways to meet the student’s needs and improve the school’s overall performance by exploring non-monetary resources.

Theme 2 - Principal strategies: Practice as a champion

The principal took a hands-on approach to collaborating with colleagues from the planning stage to the actual construction of facilities. Recognizing the limited budget for initiatives, he prioritized spending on “hardware” (facilities) as he foresaw the student need for authentic experiential learning and gathering places.

“Due to limited resources, I decided to prioritize investing in facilities over the curriculum. I believe that improving our facilities can create a more positive learning environment for our students.”

Principal

He then encouraged a free flow of ideas among his team to achieve the best outcomes. Together, they devised a plan to use their limited money to support experiential learning development by building a café, designing a thinking workspace, a “gym science”, and an eco-lab. To address the shortfall in financial resources, the principal purchased materials from an online store and contacted skillful janitors and colleagues convincing them to stay after school to do the renovations. Thus, they completed the project at a much lower cost than if they had hired a contractor.

“It’s unbelievable that the principal and janitor used a big hammer to break down the wall and built the cafe by themselves, purchasing all the necessary materials.”

Vice-Principal

Theme 3 - Teachers’ reaction: Unleashing the innovative potential of teachers

The teachers said the principal removed barriers that were impeding their ability to innovate. The availability of new facilities served as a catalyst for stimulating pedagogical change and sparking innovative thinking among the teachers. This encouraged the teachers to design a physical space that promoted experiential learning and pushed the students to reach their full potential. Some teachers began thinking about developing a curriculum that would effectively use these new facilities and sought to design innovative projects to improve their students’ education quality.

“The new facilities have inspired me to think outside the box and design a learning environment that encourages experiential learning and pushes students to reach their full potential.”

Teacher A

Notably, despite allocating most of the savings towards these new initiatives, the teachers reported that the principal did not reduce the daily operational expenses of any department, ensuring that stable financial support was provided to all areas of the school.

“Despite implementing numerous new initiatives, all budget plans were approved under his leadership.”

Vice-Principal A

Scaling up innovative practice in 2020/21

Theme 1 - The perception of utilizing WSF: Confident in moving away from reliance on WSF

The principal was confident in the school’s ability to identify and secure alternative sources of funding to support their future initiatives, moving away from relying solely on the WSF. His plan involved using the WSF to sustain four new facilities for experiential learning, as the expenses were reasonable and well worth the investment in providing innovative educational opportunities for their students.

“We have four new facilities for experiential learning that we sustain through using WSF. The expenses are reasonable and well worth the investment in providing innovative educational opportunities for our students.”

Principal

The principal claimed that the new facilities demonstrate the potential of the school’s financial management and innovative teaching methods, which will help them secure external financial support for future initiatives.

“I have four successful cases that we can use as examples to secure external financial support for future initiatives, showing that we can pursue innovative funding opportunities and reduce our reliance on WSF.”

Principal

Theme 2 - Principal strategies: Empowering teachers to become pro-active innovators

The principal played an important role in empowering teachers to become pro-active innovators by supporting them in seeking resources necessary for implementing their own initiatives. The principal first showcased the school’s facilities and experiential learning to external parties, establishing connections and broadening funding sources beyond their reliance on WSF.

“Our principal’s efforts to promote our school’s success stories, particularly our achievements in student learning and innovative facilities, have attracted the interest of external parties who have expressed a desire to offer additional financial support.”

Teacher B

Meanwhile, the principal collaboratively established expected student learning outcomes with colleagues interested in initiating the new projects. The principal then encouraged those teachers to apply for funding opportunities that supported future innovative teaching practices and expected learning outcomes. He guided and reviewed the teachers’ proposals to ensure they aligned with the school’s academic direction.

“He provides direction and guidance allowing us to develop proposals based on our own ideas. He reviews and evaluates our proposals to ensure alignment with his vision for the school’s growth and sustainability.

Teacher C

Theme 3 - Teachers’ reaction: Teacher-led resource mobilization

Since the beginning of 2021-22 academic year, several teachers sought resources to improve student growth and development. These teachers placed their trust in the principal due to his successful track record in transforming limited resources into radical changes in the school. His success and strong networks with potential funders resulted in widespread enthusiasm among other teachers to apply for funding for AI-STEM education.

“After successfully securing AI-STEM funding, three more colleagues approached us to help write a funding proposal for mindfulness education, which we were able to secure the following year for a total of seven million dollars.”

Vice-principal B

The teachers’ efforts was reinforced by $HK3 million in grants (USD450,000) allocated to the school to develop its AI-STEM program and STEM Lab. The grants were external funding gained from charity foundations. This funding resulted in new prospects for groundbreaking projects and ongoing progress and development in the school, resulting in three additional funding opportunities for mindfulness education totaling $HK7 million planned for 2021/22.

The school’s new entrepreneurial spirit did not appear to incite any resentment from the teaching staff. Teachers reported that anyone could apply for funding and receive their earned resources. Those who did not aim to initiate any projects did not appear to object to the distribution of resources.

“There is no resentment or jealousy over resource allocation. Everyone has the opportunity to apply for funding and earn what they work for. Don’t forget that it also implies workload.’

Teacher A

Discussion

Innovation in teaching and learning is a deliberate craft honed by school principals who strategically allocate their budgets. The study’s findings reveal that the principal played a crucial role in driving innovation using the WSF. The principal’s perception of WSF utilization was largely influenced by his experiential encounters and challenges in managing a meager budget while striving to promote equity and innovation in his school. The primary concern about the WSF primarily revolves around its inflexibility and inadequacy. The rigid administrative procedures associated with the WSF appear to significantly impede creativity in catering to students’ needs. The WSF policies around allocating resources to schools often exacerbates existing disparities, favoring wealthier schools. Despite the principal using the WSF as the primary source for initiating innovations in his school in the second year, the credit also goes to the principal’s strategies for saving resources. The principal stated that the WSF did not adequately provide for resources to address diverse student needs. He claimed that the WSF is best suited for a limited set of needs, such as facilitating general school operations, piloting initial innovations, and supporting the operational expenses of innovation. Thus, to enable schools to promote sustainable innovation, there is an urgent need to move beyond reliance on WSF.

The principal demonstrated layered leading strategies in managing and allocating his budget to maintain school operations and promote innovations. In the first year, the principal focused on formulating a consensus among teachers and students regarding the school’s development direction. This was achieved by enhancing teacher planning capacity, consulting with students, and sharing educational goals with teachers. Building on this, the principal encouraged innovation and exhibited infectious enthusiasm to bring the initiatives to fruition in the second year. By strategically planning initiatives with core team members and being involved in every working process, he was able to actualize the experiential learning initiatives with a limited budget while passing on his passion to the teachers. The renovations served as a symbolic catalyst for subsequent changes. In the third year, the principal shifted his role from being a facilitator, to mainly focusing on seeking funding for teachers with innovative ideas. He continuously acknowledged teachers’ contributions and guided colleagues to further elaborate their ideas, ultimately assisting them in compiling proposals for funding applications. Throughout the three years, the principal’s strategies involved scaling up his influence by practicing what he preached. Notably, the principal never raised the issue of financial difficulties to the teachers, but instead utilized school savings to actualize his innovative ideas while seeking potential funders to support the teaching staff.

Teachers underwent role changes from being learners to collaborators to leaders over the three years. In the first year, the teachers acted as learners who agreed with the school’s development direction while awaiting radical changes. They demonstrated their eagerness to revise and enhance their plans multiple times under the guidance of the principal. In the second year, the availability of new facilities served as a catalyst for pedagogical change and sparked innovative thinking among the teachers, encouraging them to become collaborators in designing an environment that promoted experiential learning. In the third year, the experience of experiential learning resulted in widespread enthusiasm among the teachers to become leaders, as they composed proposals to apply for funding for various initiatives. Despite limited financial resources in the school, there were no criticisms regarding funding allocation. Most teachers were unaware of the tight fiscal position of the school and the criteria used by the principal to allocate funds to new innovations. Despite the availability of relevant information, many teachers seemed oblivious to these financial matters.

Theoretical implications

The study’s findings regarding the principal’s perceptions of the WSF align with existing literature beyond Hong Kong highlighting a school’s tendency to allocate a significant portion of their budget towards staffing and maintenance (Baumol, 2012). However, the participant school’s staff did not appear to have any concerns about prioritizing initiatives. In reality, the principal used the WSF as the primary source for piloting and supporting daily operational costs associated with initiatives. While implementing such initiatives required significant effort to save resources, the findings suggest that the WSF was adequate for sustaining its innovative endeavors, even if not completely sufficient for the radical changes.

This study adds value to the existing literature on principal leadership by shedding light on how principals can utilize WSF and government regulated financial management mechanisms to foster teacher growth. Prior research has largely focused on leaders’ innovation and how they manage their budget (Bush & Oduro, 2006; Palardy, 2008). The findings of the present study show how a principal tactfully used regulated financial management mechanisms to encourage teachers to initiate projects following his example initiatives. This finding indicates that the principal was able to expand the management of the WSF beyond the typical budgeting for the school’s day-to-day operations, and this led to some teachers acquiring the energy and skills to advance their own initiatives.

The findings also demonstrate how principals encourage consensus-building and advocacy for innovation, thereby increasing innovative practices through the effective use of financial resources. This study’s findings unlock new avenues for financial resource management studies, as principals not only comply with regulations but also devise ways to conserve and acquire funding for school initiatives. Future studies should investigate how principals use their budgets creatively to foster and sustain innovation.

Practical implications

The WSF initially played a significant role in promoting small-scale innovation. However, afterwards, its focus shifted toward sustaining the innovation so that it became a regular part of school operations. Such sustainment was revealed by the incorporation of new facilities into the experiential learning curriculum by the teachers with support from the WSF. Studies have mainly pointed to the limitations of WSF in spurring radical initiatives (Chambers et al., 2010). However, the present findings indicate that while WSF may have limited ability to support radical initiatives, effective allocation of financial resources can still enable sustained innovation.

Unlike previous findings showing that teachers are often dissatisfied with school funding decisions (REFs), the present study findings revealed that many teachers were relatively indifferent towards financial matters. This attitude appears to have facilitated the smooth allocation of financial resources for new initiatives. Future studies should explore the cause and other potential influences of this issue.

Policy implications

The principal’s perceptions of the WSF reveal a concerning trend of exacerbating school inequity. This finding underscores an important issue regarding WSF policy. Schools that serve students with special needs require greater resources to provide an equitable education. Despite this, typical funding allocation is solely based on the number of students and thus fails to address the unique needs of each school community; therefore, schools with greater needs based on their student profiles often receive insufficient funding further perpetuating pre-existing educational inequities while negatively impacting their performance and ability to attract students and parents. Accordingly, there is a pressing need for a more equitable approach to funding education that prioritizes the diverse needs of students and schools. This could involve adopting a needs-based funding formula and providing targeted support for smaller schools that promotes equitable resource allocation and successful outcomes for all students.

Limitation and conclusion

Typical of case study research, the findings of the study cannot be generalized. However, the research aims to address a question that has seldom been explored – the use of WSF to spur innovation in schools. Financial management in schools is often opaque and seldom publicly disclosed or discussed in the research. The school was purposely selected because it had previously struggled with WSF, yet it overcame these challenges while using WSF to foster innovation for its students. By conducting a case study, the author was able to investigate the interactions between the school’s principal and teachers in-depth, focusing on gaining a deep understanding of the dynamic changes in the school’s culture and budgeting practices. This approach is particularly valuable, as many schools are currently facing challenges with their WSF. Another limitation concerned the length of the study. Although three years may appear sufficient for understanding the impact of a funding decision, ideally a longer period would have provided better evidence of the sustainability of the initiatives. Our study offers insights that can advance the knowledge of principals and other stakeholders, exploring the possibility of using various leading strategies to leverage WSF for school innovation and enhancing school sustainability.

In conclusion, this case study has revealed the significant impact that a principal’s character, in this case his entrepreneurial traits, can have on a school’s ability to effectively use its WSF in maintaining operations and fostering innovation. By actively engaging with staff, advocating for innovation, seeking resources, and mitigating risks, the principal was able to transform a failing school into an innovative educational one. These findings align with studies on teacher entrepreneurial behavior (Ho et al., 2021; 2022), which suggest that individuals with entrepreneurial characteristics tend to enact a series of competencies and attributes that enable them to seize opportunities to scale up innovation in schools. Consequently, the author argue that a deeper understanding of the entrepreneurial behaviors exhibited by school leaders is crucial for promoting the effective utilization of WSF and driving positive change in schools.