1. Introduction

The European Union (EU) has a long-standing commitment to sustainable development, recognizing its importance in achieving social, economic, and environmental goals. EU funds play a significant role in advancing sustainable development in member states, directly and indirectly impacting various aspects of society. The impact of EU funds on sustainable development is substantial, touching upon various aspects of social, economic, and environmental well-being. These funds play a critical role in supporting member states' efforts to achieve a more sustainable and prosperous future, while also contributing to global sustainability goals such as the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The application of successful EU funds absorption models on sustainable development is important for several reasons. By effectively utilizing EU funds, member states can promote sustainable development and address various economic, social, and environmental challenges. Efficient absorption of EU funds ensures that resources are allocated optimally and used effectively to address sustainable development priorities. This can lead to positive economic growth, job creation, and improved living standards for citizens. EU funds often support research and development projects, technology transfer, and innovative solutions to sustainable development challenges. By absorbing funds effectively, member states can foster innovation in key areas, such as renewable energy, waste management, and sustainable agriculture. EU funds aim to reduce economic disparities among regions by supporting less-developed areas. By applying successful absorption models, countries can ensure that funds reach these regions and contribute to sustainable development goals, such as poverty reduction and social inclusion. Effective EU funds absorption can attract further investments from both public and private sectors, amplifying the impact on sustainable development. This could lead to the establishment of new businesses, infrastructure improvements, and increased competitiveness. Applying successful absorption models requires strong coordination among various stakeholders, including national and regional authorities, private sector entities, and non-governmental organizations. This can lead to better policy coherence and the establishment of integrated approaches to sustainable development. Implementing and managing EU-funded projects requires administrative and technical capacity. By applying successful models, member states can strengthen their institutions, improve governance, and develop better project management skills, ultimately benefiting the overall sustainable development efforts. Successful absorption models often include robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, enabling member states to track the progress of funded projects and measure their impact on sustainable development. This feedback loop can inform future policy decisions and improve the effectiveness of EU funds.

The main advantage of EU funds is that they represent financial resources that do not need to be repaid and are part of the total investment, thereby directly influencing the economic growth of a certain country (Vukašina et al., 2022). In their study, Florkowski et al. 2022 emphasize that co-financing of projects funded by EU funds has a significant impact on the further development of individual regions, enabling the implementation of multiple development projects. The research conducted by Walesiak et al. 2023 confirms the effects of EU funds on individual regions, where improvements in the level of social cohesion and reduction of regional inequalities are evident. Management and strategic planning are the key to success, and projects and development have no place for politicization and promotion (Šostar, 2021a).

1.1. Problem Statement

European Union (EU) funds, as an accessible source of financing for various project ideas and a factor with the potential to contribute to sustainable local, regional, and national socio-economic development, are becoming an increasingly prevalent topic of discussion in both professional and scientific circles. The Republic of Croatia follows the trend of other countries, in which stakeholders have behaved similarly: as the number of EU funds increased in content and scope, more stakeholders became involved on one hand in the preparation and implementation of projects, and on the other hand, in expert discussions on various issues related to EU funds in various ways. Stakeholders who deal with the preparation and implementation of projects financed through EU funds are mainly focused on a single clearly defined goal, which is to achieve as much funding as possible through as many projects as possible. Some countries are extremely successful in implementing many projects through EU funds financing. When entering a particular project, it is essential to decide which project to choose. To make the decision-making process as high-quality as possible, it is necessary to recognize the need for decision-making and be aware of the time constraints that exist when making decisions. Selecting the most successful model for absorbing funds from EU funds is undoubtedly the foundation for increasing economic activities and, ultimately, the regional development of countries. This research deals with the reasons for the lower success of certain countries in absorbing funds from EU funds and the development of a unique model for efficiently attracting funds from EU funds applicable to the Republic of Croatia and other countries.

1.2. Significance of the Study

The application of successful EU funds absorption models on sustainable development is significant for several reasons. By effectively utilizing EU funds, member states can promote sustainable development and address various economic, social, and environmental challenges.

This research will provide a systematic and comprehensive review and analysis of existing knowledge in the field of research, which relates to the specificities of regional development under the influence of EU funds. The expected contribution to economic science in a theoretical sense stem from the development of scientific knowledge and thought on the importance of increasing the number of development projects that will improve the absorption of funds from the European Union, thus increasing economic activities in Croatia and the region. The expected contribution to economic science in an applied sense is based on formulating the "EU Funds-based Regional Development Model," which is based on the application of knowledge, the adoption of good practices and experiences of stakeholders, and considering relevant indicators from available sources. The research itself will be conducted in four European countries (Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary, and Poland), which adds value to the scientific contribution based on different regional backgrounds. The most significant contribution will be through testing the "EU Funds-based Regional Development Model," which will be applicable to the Republic of Croatia, countries in the region, and other European countries over an extended period. Finally, research on the impact of EU funds on the regional development of beneficiary countries is significantly less represented and very modest, only in the "rise" of systematic scientific research. This study aims to fill gaps in the research sense and stimulate the thinking of key stakeholders responsible for regional development, who should eventually understand the importance of defining regional policy focused on EU funds as the key to regional development and reducing regional differences within states. The mentioned research provides a basis for further scientific research in the field of EU funds absorption with the aim of balanced regional development.

2. Literature Review

The field of EU funds is an interdisciplinary area that involves researchers from various backgrounds, including economics, public policy, regional development, and sustainable development, among others. Smart planning is the key to success, especially considering the limited financial and human resources (Šostar 2021). Attitudes towards EU institutions can potentially influence the reduced number of project applications to EU funds. In their research, Crepaz and Hanegraaf, 2022, prove that the impact is almost negligible. Crescenzi et al, 2020, show in their research that love for the EU cannot be bought, which is proven by the exit of the United Kingdom from the EU despite the EU funds which had a significant impact on their development.

In their research, Ciani and Blasio, 2015, suggest that EU funds have a limited impact on local employment measures, population, and household product prices. Destefanis and Di Giacinto, 2023; Arbolino and Caro, 2021 discuss in their research the impact of EU funds on GDP, promoting regional resilience, and significant effects of the same during the COVID 19 pandemic. On the other hand, Álvarez-Martínez and Polo, 2017 confirm in their research that EU funds have a short-term effect on economic development. Charasz and Vogler, 2021, emphasize that EU funds have a long-term effect on local and state capacities and that the funds contribute to reducing bureaucracy. On the other hand, by analyzing two regression models, Kaflova, 2019, concluded that quality state governance is important for the implementation of EU regional policy.

In the context of the efficiency of EU funds, Melecký, 2018, believes it is necessary to put the co-financing activities of projects in a broader context to understand the aforementioned. Following this, Šelebaj and Bule, 2021, in their research, conclude that support from EU funds has a strong positive impact on almost all business indicators of companies and other project applicants. Also, Muraközy and Telegdy, 2023, emphasize the impact of EU funds on company inputs, workforce productivity, and capital intensification.

Lautinger, 2022; Van Wolleghem, 2022, in their studies, highlight the reasons for insufficient absorption of funds from EU funds, emphasizing time and accounting mechanisms, administrative and financial capacities, and the nature of the funds themselves as the main limiting factors. Kersan-Škrabić and Tijanić, 2017, emphasize that the key to good absorption is investment in human resources, decentralization, investments, institutional framework, and infrastructure development. One of the problems, as pointed out by Medve-Bálint and Šćepanović, 2020, is that a large share of EU funds is absorbed by foreign companies that take money out of the country. There are several studies that demonstrate the relationship between the quality of public administration and the absorption capacity of projects funded by EU funds (Baun et al. 2017; Terracciano et al. 2016). In their research, Mendez et al. 2022 emphasizes that regional government does not have an influence on the administrative performance of EU funds.

Fidrmuc et al. 2019; Bourdin 2019 confirm that there is a significant impact of non-refundable funds on a certain area, emphasizing a greater impact in larger centers than in the periphery. Blouri and von Ehrlich 2020 use a general equilibrium model to assess the impact on wages, productivity, and infrastructure. Crucitti et al. 2023 notes that research should not only be guided by the amount of absorbed financial resources, but also by the way these resources are distributed. In his study, Hageman 2019 highlights the importance of capacity, emphasizing that poor capacities strongly affect absorption power and the inability to reduce regional inequalities.

Every crisis impacts the efficiency of EU funds on a particular environment or investment. Correctly directed funds in case of any market anomalies are the key to success. The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected the crisis worldwide while the EU tries to finance further development of its regions with strong recovery mechanisms (Sakkas et al. 2021). Several studies are investigating the results of the Recovery Plan for Europe as a whole, as well as those of specific countries (Bankowski et al., 2021; Pfeiffer et al. 2021; Picek 2020).

When speaking of conducted research related to EU funds and their impact on the regional development of certain countries, there aren't many authors who have taken up the challenges these countries face. According to Kersan-Škrabić et al. 2017, it is evident that some studies have attempted to capture the comprehensive relationship between administrative capacities, political governance, and the implementation of projects funded by the EU. Cunito et al. 2021 emphasizes that there is no adequate model for monitoring and analyzing the impact of EU funds on regional development, and that this depends on a range of factors while on the other side Maras 2022 confirm that there is a great connection between European funding and reducing of regional desparities especially when including regional and local authorities to the processes (Marcu et al. 2020).

When we talk about the capacities necessary for attracting and utilizing funds from the European Union, they are divided into three categories: Administrative capacities; Financial capacities; Macroeconomic capacities (Šostar 2021b).

Administrative capacity primarily refers to the ability of stakeholders individually, but even more so the ability of the system, to carry out tasks related to the preparation and implementation of all prescribed and entrusted procedures related to the funds of the European Union. In their research, Țigănașu et al. 2018 prove that high-quality institutional management, as leading dimensions of administrative capacity, have a positive impact on the absorption rate of funds from EU funds.

Financial capacities refer to the abilities of stakeholders and the system to fully finance these procedures. Macroeconomic capacity relates to the limitation whereby a country is constrained in the amount of funds it can draw from the Structural Funds. According to Aivazidou et al. 2020, less successful local authorities need to change their strategic focus and prioritize strengthening their administrative capacities rather than increasing the absorption of funds from EU sources. Due to capacity limitations, Madeira et al. (2021) emphasizes the importance of following a smart specialization strategy and focusing on areas that will bring us the most benefits in financing regional development. A very interesting study presented by Incaltarau et al. 2020 highlights the role of the government in reducing corruption to increase the absorption of funds from EU sources, which have a direct impact on the regional development of specific regions.

There is research on methods of measuring the impact of EU fund resources on the macroeconomic indicators of recipient countries. Two approaches are mentioned: the econometrics approach and the simulation model approach. In the simulation models, the HERMIN, HERMES, QUEST II, and ECOMOD models appear (Bradley et al. 2022; Surubaru 2021; Piątkowski 2020; Roeger et al. 2022). The macroeconomic effects of EU funds are visible in employment, infrastructure development, GDP changes, and personal consumption. As Poland has historically been the most successful country in attracting funds from the EU, it is important to analyze what it has done to be successful (Szlachta 2004).

It is evident that the effect of EU funds is greater in some regions and smaller in others. In the poorest regions, the spillover effect does not contribute to reducing regional inequalities but represents a great opportunity for the future period (Maras 2022). It has also been proven (Aiello et al. 2019) that less developed regions require more financial resources due to having higher administrative and bureaucratic challenges, particularly due to the lower level of capacity of local authorities.

3. Research objectives and hypothesis

The subject of the research is the absorption of funds from EU funds and their impact on the regional development of Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary, and Poland. The analysis aims to investigate the efficiency of absorbing funds from EU funds, the impact of these funds on the regional development of the countries, and the reasons for such impacts. Each country has its own approach to regional development and different regional policy priorities. However, all countries belonging to the eurozone have a common, shared goal, which is evident in balanced regional development with positive microeconomic and macroeconomic indicators. EU funds are the right path to success, including the human and material potentials of each of these countries.

Figure 1.

Hypotheses of the study.

Figure 1.

Hypotheses of the study.

The purpose of the research is to familiarize the attitudes of key stakeholders involved in the preparation and implementation of projects from EU funds in Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary, and Poland regarding the level of absorption of funds from EU funds, their impact on regional development, and the reasons for such impacts, through testing the "EU Funds-based Regional Development Model." Based on the conducted research, the aim is to confirm the "EU Funds-based Regional Development Model," which would be applicable to the Republic of Croatia. The conducted research would be applicable to the Republic of Croatia, countries in the region, and other European countries. In fact, the work aims to increase the absorption of funds from EU funds that are available and will become available to the Republic of Croatia. The main reason for choosing the mentioned countries is that they are EU members and have gone through the same processes that the Republic of Croatia. They had access to the same EU funds that Croatia now has, and they receive funds from structural and cohesion funds that Croatia received. Hungary and Slovenia are ideal candidates due to their geographical location, historical heritage, and mentality similar to the Republic of Croatia. Poland was chosen because it is the country that most effectively uses EU funds, having the highest level of utilized funds available to it through past EU programming periods. As a result, Poland was the only EU country not affected by the global financial crisis in 2008.

4. Methodology of research

Given the established hypotheses, secondary data will be systematically researched using scientific literature in the fields of economic and regional development as well as EU funds. The deductive method will be used, where hypotheses will be attempted to be proven, and the inductive method, through which general conclusions will be reached. Abstract methods will be used to separate the essential from the non-essential, and the classification method will be applied using specialization and generalization methods. In addition, the systematic analysis method and synthesis method will be used, as well as the dialectical approach, meaning that phenomena will be observed as dynamic as opposed to a static approach. Also, based on the developed "EU Funds-based Regional Development Model," the same will be examined through a questionnaire, as well as using existing statistical indicators to test the applicability of the model to the Republic of Croatia. Primary research will be conducted in four countries (Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary, and Poland), while the respondents will be key stakeholders in these countries involved in the processes of preparation and implementation of projects from EU funds. The total number of respondents will be 244 experts in the preparation and implementation of projects from EU funds in Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary, and Poland. All respondents are employed in institutions dealing with the preparation and implementation of projects from EU funds or work as consultants in the preparation of documentation for attracting funds from EU funds. These are individuals who possess knowledge, experience, and expertise in the field of preparation and implementation of development projects, and they are positioned as key to regional development in each country. Respondents participated in the study by defining their experiential attitudes, where their perception of the researched issue was recognized.

Before carrying out the research procedure (secondary and primary), a "Model of regional development based on EU funds" was created.

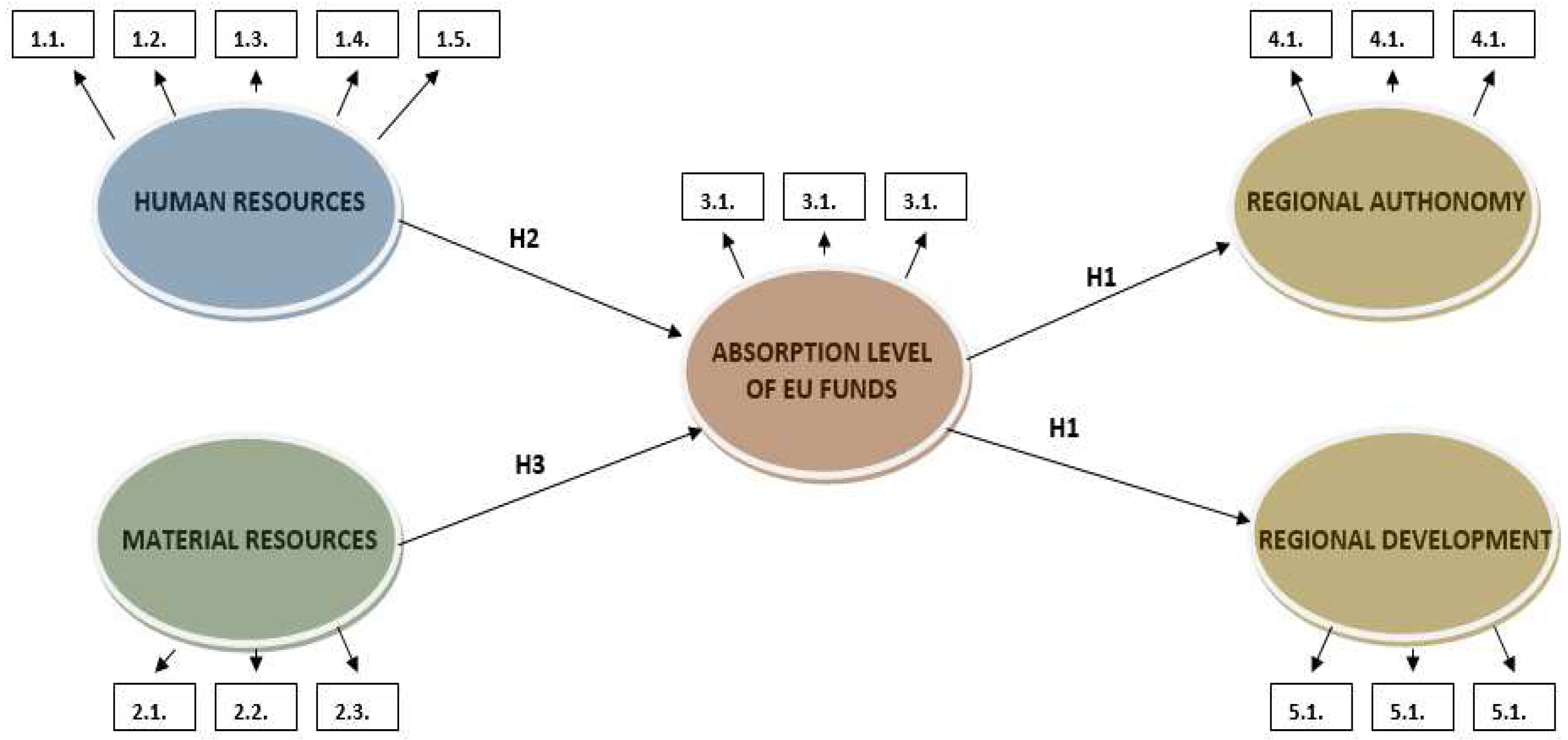

Figure 2.

Model of regional development based on EU funds.

Figure 2.

Model of regional development based on EU funds.

The above graph shows a model of regional development based on EU funds. Key areas are defined: human resources, material resources, the level of EU fund absorption, regional autonomy, and regional development. Indicators are set for each area and further elaborated through a series of questions posed to respondents for the purpose of examining the above-mentioned model. The indicators are divided as follows:

Human resources

- 1.1.

Education at all levels in project preparation for EU funds

- 1.2.

Awareness of financing opportunities from EU funds

- 1.3.

Creativity of key people in preparing projects for EU funds

- 1.4.

Motivation of key people in preparing projects for EU funds

- 1.5.

Team collaboration in preparing projects for EU funds

Material resources

- 2.1.

Financial capacities for co-financing projects from EU funds

- 2.2.

Alignment of strategic documents with development needs

- 2.3.

Level of technological readiness for implementing projects from EU funds

Level of EU fund absorption

- 3.1.

Number of prepared projects for EU funds

- 3.2.

Contracting rate of funds from EU funds

- 3.3.

Number of successfully implemented projects from EU funds

Regional autonomy

- 4.1.

Regional competitiveness index

- 4.2.

Level of financial dependence on centralized state resources

Regional development

- 5.1.

Level of consumption

- 5.2.

Number of investments

- 5.3.

Unemployment rate

- 5.4.

Population size

- 5.5.

Level of competitiveness

Within the "Model of regional development based on EU funds", hypotheses were set that needed to be confirmed. The model was then tested with statistical analysis of the conducted questionnaire in these countries and available secondary data. The hypotheses were proven, and the model was confirmed as applicable in Croatia and EU member and candidate countries.

5. Results and discussion

By analyzing survey questionnaires in Poland, Slovenia, Hungary, and Croatia, we tested the proposed "Model of Sustainable Regional Development Based on EU Funds."

In

Table 1; the results of the descriptive analysis by scales described under the instruments are listed. The data presented are shown for each scale and for respondents within each country.

In

Table 2, the ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) is presented, which shows whether the differences between individual groups are statistically significant or not. The F-ratio must be significant if there are differences. The last column contains the confidence coefficient. If it is less than 0.05, meaning 5%, then there are differences. It is clear that all scales are different from one another, and further analysis using the post-hoc test showed that Poland has statistically significantly higher results on all scales compared to Slovenia, Croatia, and Hungary. This data speaks of clear differences between countries in various aspects and processes important for attracting funds from EU sources.

The variable "Education at all levels in the preparation of projects for EU funds" is statistically significantly different between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=311.375, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is visible that p<0.05, which is significant. It was recorded that Poland has the highest level of education for project preparation for EU funds, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Awareness of funding opportunities from EU funds" is statistically significantly different between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=195.981, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is visible that p<0.05, which is significant. It was recorded that Poland has the highest level of awareness of funding opportunities from EU funds, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Creativity of key persons in the preparation of projects for EU funds" is statistically significantly different between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=330.422, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is visible that p<0.05, which is significant. It was recorded that Poland has the highest level of creativity in project preparation, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Team cooperation in the preparation of projects for EU funds" is statistically significantly different between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=453.585, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is visible that p<0.05, which is significant. It was recorded that Poland has the highest level of team cooperation for project preparation for EU funds, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Motivation of key persons in the preparation of projects for EU funds" is statistically significantly different between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=232.979, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is visible that p<0.05, which is significant. It was recorded that Poland has the highest level of motivation for EU fund preparation, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Financial capacity for co-financing projects from EU funds" is statistically significantly different between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=391.295, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is visible that p<0.05, which is significant. It was recorded that Poland has the highest level of financial capacity for co-financing projects from EU funds, while Hungary has the lowest.

The variable "Alignment of strategic documents with development needs" is statistically significantly different between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=306.519, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is visible that p<0.05, which is significant. It was recorded that Poland has the highest level of alignment of strategic documents with development needs, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Level of technological preparedness for the implementation of projects from EU funds" is statistically significantly different between the selected countries in which the research was (F=262,464, df=3, 240, p<0,05). It is evident that p<0.05, which is significant. It has been recorded that Poland has the highest level of technological readiness for the implementation of projects from EU funds, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Number of projects prepared for EU funds" differs significantly between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=322.511, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is evident that p<0.05, which is significant. It has been recorded that Poland has the highest number of prepared projects for EU funds, while Croatia has the lowest.

The variable "Contracted funds rate from EU funds" differs significantly between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=424.083, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is evident that p<0.05, which is significant. It has been recorded that Poland has the highest rate of contracted funds from EU funds, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Number of successfully implemented projects from EU funds" differs significantly between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=360.895, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is evident that p<0.05, which is significant. It has been recorded that Poland has the highest number of successfully implemented projects from EU funds, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Regional Competitiveness Index" differs significantly between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=181.686, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is evident that p<0.05, which is significant. It has been recorded that Poland has the highest regional competitiveness index, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Level of financial dependence on central state funds" differs significantly between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=268.771, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is evident that p<0.05, which is significant. It has been recorded that Poland has the highest level of financial dependence on central state funds, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Level of personal consumption" differs significantly between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=196.417, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is evident that p<0.05, which is significant. It has been recorded that Poland has the highest level of personal consumption, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Level of government spending" differs significantly between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=15.343, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is evident that p<0.05, which is significant. It has been recorded that Poland has the highest level of government spending, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Number of investments" differs significantly between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=480.067, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is evident that p<0.05, which is significant. It has been recorded that Poland has the highest number of investments, while Slovenia has the lowest.

The variable "Unemployment rate" differs significantly between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=4.149, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is evident that p<0.05, which is significant. It has been recorded that unemployment rates are very close in the examined countries, with the perception of high unemployment being the highest in Poland and the lowest in Hungary.

The variable "Population size" differs significantly between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=134.073, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is evident that p<0.05, which is significant. It has been recorded that Poland has the largest population, while Slovenia has the smallest.

The variable "Level of competitiveness" differs significantly between the selected countries in which the research was conducted (F=448.474, df=3, 240, p<0.05). It is evident that p<0.05, which is significant. It has been recorded that Poland has the highest level of competitiveness, while Croatia has the lowest.

The main reason for this is the fact that Poland's awareness of the importance of EU funds was far ahead of everyone else. Immediately after signing the pre-accession agreement, Poland had a strong campaign on the importance of EU funds and significant investments in educating the entire regional development system for the preparation and implementation of projects according to EU methodology. In addition, strong public information campaigns and potential project stakeholders were conducted, considering the future of co-financing projects from EU structural funds. Teams at all levels were prepared to work on projects, great importance was given to motivating people, and capacities were prepared for financing large projects. Regional development policy was moving towards adapting to the current situation and needs of Poland on the one hand and EU legislation on the other. As a result, Poland achieved the best results in the number of successfully co-financed and implemented projects from EU funds, which had a huge impact on investments, consumption, competitiveness, and thus influenced the regional development of the country. The main reason for Poland's preservation from the financial crisis that recently affected the whole world is precisely these reasons. Poland is the only EU country that had growth in GDP per capita during the crisis.

In the continuation of the analysis, the results indicate the interconnection of different aspects of attracting funds from EU funds.

As part of the first hypothesis, which states that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between the absorption of European Union funds and the regional development of beneficiary countries, a hierarchical regression analysis was used.

From

Table 3, it can be seen that the adjusted R2 for the second step of the analysis is 0.767, which means that the model explained approximately 77% of the variance, and that the F-ratios are statistically significant. From

Table 3, it can be seen that the number of prepared projects for EU funds is a better predictor than the number of successfully implemented projects from EU funds. The beta coefficient of the "Number of prepared projects for EU funds" is β=0.602, t=10.283, p<0.01, and the beta coefficient for the "Number of successfully implemented projects from EU funds" is β=0.219, t=3.101, p<0.05. This data supports the posed hypothesis that there is a cause-effect relationship between the absorption of European Union funds and the regional development of recipient countries (

HYPOTHESIS 1 ACCEPTED). For a more precise explanation of the hypothesis, it should be noted that regression analysis is an indicator of correlation, not a cause-effect relationship. However, since it can be logically assumed that the direction in this case is cause-effect, we confirm the hypothesis in this way with the remark that it is about the assumed direction of influence.

According to

Table 4, the number of prepared projects is more significant than the number of successfully implemented projects. Of course, both variables are extremely important predictors for regional development, but the data show that the overall project capacity with which a country competes for EU funds is also extremely important. The assumption is that countries with a larger number of projects have a wider choice and greater opportunities to choose more projects that meet the criteria of EU funds from a larger number of projects.

To test Hypothesis 2, which states that investing in human resources increases the utilization of available European Union funds, a hierarchical regression analysis was also conducted. From

Table 5, it can be seen that the adjusted R2 for the fourth step of the analysis is 0.847, which means that the model explained approximately 85% of the variance, and that the F-ratios are statistically significant.

The variable "Education at all levels in the preparation of projects for EU funds" has proven to be a statistically significant predictor of the criterion variable "Number of successfully implemented projects from EU funds" - the regression coefficients of the hierarchical regression analysis are β=0.401, t=6.704, p<0.05. The other beta coefficients are β=0.214, t=3.178, p<0.05, for the variable "Creativity of key people in the preparation of projects for EU funds", β=0.205, t=3.209, p<0.05 for the variable "Team collaboration in the preparation of projects for EU funds ", and β=0.147, t=2.427, p<0.05 for the variable "Motivation of key people in the preparation of projects for EU funds".

As we can see according to the beta coefficients, Education at all levels in the preparation of projects for EU funds is the most important predictor, but creativity, team collaboration, and motivation of key people in the preparation of projects for EU funds are also very important. Based on these results, it can be claimed that HYPOTHESIS 2 IS ACCEPTED, i.e., this research has determined that the level of utilization of available EU funds can be increased by investing in human resources.

As part of Hypothesis 3, the claim that strengthening material resources increases the utilization of available European Union funds was examined. The hypothesis was also tested by hierarchical regression analysis. The model is also highly explained, the adjusted R2 is 0.844 or almost 85% of the variance. The measures "Level of technological readiness for the implementation of projects from EU funds", "Alignment of strategic documents with development needs", and "Financial capacities for co-financing projects from EU funds" were taken as predictor variables, while the criterion variable is "Number of successfully implemented projects from EU funds".

Table 6.

Regression beta coefficients for predictor variables "Education at all levels in the preparation of projects for EU funds", "Creativity of key people in the preparation of projects for EU funds", "Team collaboration in the preparation of projects for EU funds", and "Motivation of key people in the preparation of projects for EU funds" in relation to the criterion variable "Number of successfully implemented projects from EU funds" (Own elaboration).

Table 6.

Regression beta coefficients for predictor variables "Education at all levels in the preparation of projects for EU funds", "Creativity of key people in the preparation of projects for EU funds", "Team collaboration in the preparation of projects for EU funds", and "Motivation of key people in the preparation of projects for EU funds" in relation to the criterion variable "Number of successfully implemented projects from EU funds" (Own elaboration).

| Model |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Significance |

| |

Beta |

|

|

| 1 |

(Constant) |

|

5,810 |

,000 |

| Education at all levels in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

,893 |

30,809 |

,000 |

| 2 |

(Constant) |

|

2,168 |

,031 |

| Education at all levels in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

,544 |

10,563 |

,000 |

| Creativity of key people in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

,404 |

7,841 |

,000 |

| 3 |

(Constant) |

|

2,013 |

,045 |

| Education at all levels in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

,436 |

7,427 |

,000 |

| Creativity of key people in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

,296 |

5,032 |

,000 |

| Team collaboration in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

,227 |

3,556 |

,000 |

| 4 |

(Constant) |

|

1,307 |

,192 |

| Education at all levels in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

,401 |

6,704 |

,000 |

| Creativity of key people in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

,214 |

3,178 |

,002 |

| Team collaboration in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

,205 |

3,209 |

,002 |

| Motivation of key people in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

,147 |

2,427 |

,016 |

Table 7.

Data on the coefficient index of the suitability of the regression model.

Table 7.

Data on the coefficient index of the suitability of the regression model.

| Model |

R |

Adjusted R2 |

Change Statistics |

| Change in R2 |

Change F ratio |

df1 |

df2 |

Change in R2 |

| 1 |

,881a |

,775 |

,776 |

839,446 |

1 |

242 |

,000 |

| 2 |

,912b |

,830 |

,055 |

78,838 |

1 |

241 |

,000 |

| 3 |

,920c |

,844 |

,015 |

23,206 |

1 |

240 |

,000 |

According to

Table 8,

HYPOTHESIS 3 IS ACCEPTED, i.e., it has been determined that there is a statistically significant correlation between certain aspects of existing material resources and the quantity, i.e., number of projects from EU funds. The most important aspect of material resources relates to the "Level of technological readiness for the implementation of EU fund projects" whose beta coefficient is β = 0.432, t=8.642, p<0.01, followed by "Alignment of strategic documents with development needs" β=0.315, t=6.462, p<0.01, and "Financial capacities for co-financing projects from EU funds" β=0.232, t=4.817, p<0.01.

According to the Marcu et al. 2020., the ways to improve the absorption of funds from the EU are by increasing administrative capacities, improving project quality, better coordination among institutions, and involving regional and local stakeholders in governance. Wolleghem 2020; Aivazidou et al. 2020 also confirms in his study the importance of capacity over preferences, particularly in the assertion that decentralization, strategic planning and financial capacities play a positive role in the utilization of EU funds. It emphasizes that simplifying rules and procedures would increase absorption and implementation of the funds. Biedka et al. 2021 emphasizes the importance of investing in human resources as a key driver of regional development and ensuring high-quality project application and implementation. Pîrvu et al. 2019 emphasize the importance of changing the strategic orientations of EU cohesion policy and directing funds towards innovation, as well as social and environmental strategies. The results of the research conducted by Šostar 2021b emphases the importance of human resources, not only in regional planning, but especially in the preparation and implementation of projects funded by EU funds. People are a very important factor; in the end a higher level of education means a larger number of projects. It has been proven that many countries have problems due to the low level of education for the preparation and implementation of projects from EU funds. People are wealth and investing in human resources is investing in the future. Problems that arise during the preparation of projects for EU funds are also problems of financial capacity. It often happens that less developed countries, regions, cities, villages, have low annual budgets with insignificant financial resources allocated for co-financing projects. Those underdeveloped regions that need investment in development and technology suffer the most. Compliance of strategic documents with the projects to be applied for is the basis for quality planning. Large bureaucracy and administration are visible, and it is necessary to minimize it in compliance with the laws and regulations and rules of the tender. The study of Šostar et al. 2017 explains how poor implementation of public procurement procedures leads to the return of money from already funded projects, which is a direct consequence of insufficient investment in human resources.

5. Conclusions

The European Union's regional policy is designed to reduce economic and social disparities between member states by supporting regional development. The European Union implements its regional policy through cohesion policy. By co-financing projects in the areas, it covers, the development of individual regions is encouraged. However, it does not necessarily mean that more approved funds from EU funds result in greater regional development. Therefore, we need to measure the real effects and impacts of attracted funds on regional development within each fund-using country. EU funds have had a strong impact on the regional development of fund-using countries. The best example is the economic crisis (2008) that affected most European and other countries, which drastically reduced investments and led to a decline in standards in these countries. Poland, as a country that has directed all its resources to exploit available funds through development projects, managed to avoid the crisis, as one of the few countries, and experienced slight GDP growth.

To identify the main problems countries, face in absorbing funds from EU funds, to determine differences in the approach to regional policy, and to establish successful models of absorption of funds from EU funds, research was conducted in Croatia, Poland, Hungary, and Slovenia. For this purpose, a unique "EU Fund-Based Regional Development Model" was established, within which hypotheses were set that needed to be confirmed. Then the model was tested by statistical analysis of the conducted questionnaire in these countries and available secondary data. The hypotheses were proven, and the model was confirmed as applicable in Croatia and member countries as well as candidate countries of the EU.

The research results show the importance of human resources, not only in regional planning but especially in the preparation and implementation of projects financed from EU funds. People are a very important factor, ultimately a higher degree of education means a larger number of projects. It has been proven that many countries have problems due to a low level of education for the preparation and implementation of projects from EU funds. The degree of readiness of projects is important when issuing public calls for project delivery. Only those with completely prepared documentation can apply for the competition. The competition itself lasts a very short period, which means that if the project is not ready or in the final phase of readiness at the time of the competition announcement, there is a high probability that it will not be able to apply for the competition. In this way, a large part of the funds allocated for a particular country remains unused. To have a larger number of ready projects on time, it is crucial to have a satisfactory number of people at all levels educated for the preparation and implementation of projects financed from EU funds. Also, there is a great need for informing about the possibilities of financing projects with EU funds. Indeed, many potential applicants are not at all aware of the possibility of financing their projects. They either have not heard of any possibilities, or have heard but not enough, or have heard enough but do not trust and are skeptical about it. Therefore, it is important to inform the public daily through various media about the possibilities of financing projects from EU funds. Here, the connection between the level of education and information can be emphasized, because it is not a rare case that people who should convey information about current competitions from EU funds do not have enough information themselves or are late in conveying them to target groups. For this reason, it is important to adequately educate these people and "push" a policy of daily information transfer to potential users of EU funds. Sometimes it is not enough to just educate people for the preparation and implementation of projects from EU funds. People who deal with this work must have an appropriate degree of creativity. Insufficient creativity can turn a high-quality project idea into an average project, while a creative person can turn an average idea into a quality project. For this reason, it is necessary to select individuals who fit the profile of people who have the potential to be successful in project management so that the emphasis of projects is placed not only on quantity but also on quality. In the preparation and implementation of projects financed from EU funds, it is important to work as a team. Many projects require gathering all stakeholders who directly or indirectly have some influence on the project or will, in turn, be directly or indirectly affected by it and their environment. It is necessary to "gather minds" and present the best possible solution to the satisfaction of all stakeholders. When preparing projects, it is important that project partners, in addition to the applicant, participate actively and that their needs and resources are maximally utilized by involving them in all processes of application and implementation of projects. For the entire project to function, it is necessary to work as a team from the beginning to the end of the project implementation. Often such team cooperation leads to cooperation of the same partners in the future, which is an indicator of quality and satisfying teamwork. All of the above is important in the processes of preparation and implementation of projects financed from EU funds, but if the persons responsible for initiating regional activities through the preparation and implementation of projects financed from EU funds are not motivated enough, the projects will not be of high enough quality, the number of them will be insufficient, and all this will ultimately lead to poor absorption of funds from EU funds. How to motivate an individual, one might ask. The preparation and implementation of projects is a very complex process, requires a lot of knowledge, skills, and experience, and should certainly be adequately paid. The individual is also motivated by the environment in which they work. Interpersonal relationships, workspace, an organized reward system are all factors that lead to the satisfaction of an individual who thus increases the quality, speed, and efficiency of their work.

Problems that arise during the preparation of projects for EU funds are problems of financial capacity. It often happens that less developed countries, regions, cities, villages, have low annual budgets with insignificant financial resources allocated for co-financing projects. The most "suffering" are those underdeveloped regions which need investment in development and technology the most. Projects that the EU co-finances through available funds mostly must be co-financed by the applicant and partners on the project in a certain percentage. These percentages range between 10-50% of the total value of each project. This, at the very start, creates limitations that are practically unsolvable. In the end, this problem leads to the absorption of funds for investment and development projects only by those regions that are already sufficiently developed and have a large amount of funds at their disposal. Those small, underdeveloped regions, without financial capabilities, are again left forgotten. Thus, the differences between the regions deepen. This problem encompasses most countries, some more, some less, and the only solution is the involvement of state authorities through regional development policy and co-financing policy of projects crucial for the development of a particular region. Strategic documents are sometimes made "spontaneously", without any concrete direction of development, without an idea, without a real desire to achieve a satisfactory level of development. Strategic documents are prepared without consulting the "little man", without lower levels where problems exist, which often leads to creating wrong development priorities with measures that cannot help those most in need. These strategic documents often end up in "drawers", without real application, with "wandering", many unknowns, and without problem-solving. Development strategies should represent the real state, analyze the current situation for given goals over a certain period. Such documents must be aligned with strategic documents at the national and EU level, and the content must be focused on addressing pressing issues and balanced, sustainable development of regions and the country. However, pressure must be exerted on the implementation of these documents and the sanctioning of disinterested actions. Proactivity in their realization is the key to success for the beneficiaries. The research has also shown the relationship between applied projects, approved projects for financing, and truly implemented projects for which funds have been fully paid. Many prepared and applied projects do not necessarily mean a high level of absorption of funds from EU funds. Here, the relationship between quality and quantity can be observed. As EU funds are associated with very large financial resources, "instant consultants" often appear in the process of project preparation and implementation. These are individuals without sufficient knowledge, skills, and experience in project preparation and implementation, with an emphasis on hyper-production, with a low degree of quality. These projects are rarely approved for financing, but this type of "consultant" charges well for their service. Another situation that arises is that projects are approved for financing, but they are very difficult or impossible to implement, and when the first major problem arises in implementation, funds must be returned to the EU. All the above directly influences the regional development of a particular country and the reduction of regional differences within it. However, the question arises as to why some countries are more successful in absorbing funds from EU funds than others. The best positive example is Poland, as a country that has used the most funds from EU funds. One of the reasons is that Poland had a vision. Regional policy, which was designed at national levels, served the absorption of financial resources from EU funds. Preparations started years before accession, so Poland was ready for EU funds. Great efforts were invested in preparing institutions, organizations, and entrepreneurs for the incoming funds. A strong information campaign, coupled with a series of workshops and educational cycles, strengthened institutional and human capacities. Projects began to be prepared in advance, with an emphasis on the highest degree of readiness of project documentation when funds become available. The result of this is many quality projects ready for implementation at the moment of the announcement of the competition. The implemented projects covered all areas of development, which is the result of striving for uniform regional development. Large financial resources obtained from the EU through projects have stimulated investments, increased consumption, and raised the level of competitiveness of the Polish economy to a very high level. This has affected the fact that Poland is the only EU country that has seen an increase in economic activities during the financial crisis that recently engulfed the entire world. Despite this, Poland recorded growth, which is certainly the result of a large financial "injection" by the EU through project financing.

In this paper, a unique "Model of regional development based on EU funds" has been established, and it has been proven through the same how the model is functional and applicable to the Republic of Croatia, as well as other EU countries over a longer period. As there is a cause-and-effect relationship between the absorption of EU funds and the regional development of beneficiary countries, it is crucial to invest in human and material resources to raise the level of absorption to a high level.

Author Contributions

Cconceptualization, Marko Šostar; methodology, Marko Šostar;.; formal analysis, Marko Šostar; investigation, Marko Šostar, Vladimir Ristanović and Chamaru De Alwis; resources, Marko Šostar, Vladimir Ristanović and Chamaru de Alwis; data curation, Marko Šostar; writing—original draft preparation, Marko Šostar, Vladimir Ristanović and Chamaru de Alwis; writing—review and editing, Vladimir Ristanović; supervision Marko Šostar; project administration Marko Šostar; funding acquisition, Marko Šostar. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study are not publically available due to ethical and privacy issues.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arbolino, Roberta, Di Caro, Paolo. 2021. Can the EU funds promote regional resilience at time of Covid-19? Insights from the Great Recession. Journal of Policy Modeling. 43(1), 109-126. [CrossRef]

- Aiello, Valentina, Reverberi Pierre Maurice, and Brasili Cristina. 2019. Framework for comparative analysis of the perception of Cohesion Policy and identification with the European Union at citizen level in different European countries. Regional Diversity. Italy. Emilia-Romagna Calabria. University of Bologna.

- Aivazidou, Eirini, Cunico Giovanni and Mollona Edoardo. 2020. Beyond the EU Structural Funds’ Absorption Rate: How Do Regions Really Perform? Economies. 8(3), 55. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Martínez, María Teresa, Polo, Clemente. 2017. The short-run effects of EU funds in Spain using a CGE model: the relevance of macro-closures. Economic Structures. 6. [CrossRef]

- Bankòwski, Krzysztof, Ferdinandusse Marien, Hauptmeier Sebastian, Jacquinot Pascal, and Valenta Vilém. 2021. The macroeconomic impact of the NextGenerationEU instrument on the euro area. Occasional Paper Series, 255. European Central Bank (ECB).

- Baun, Michael, and Marek Dan. 2017. The limits of regionalization: The intergovernmental struggle over EU Cohesion Policy in the Czech Republic. East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures, 31(4), 863–884. [CrossRef]

- Biedka, Wanda, Herbst Mikołaj, Rok Jakub and Wójcik, Piotr. 2021. The local-level impact of human capital investment within the EU cohesion policy in Poland. Papers in Regional Science. 101. [CrossRef]

- Blouri, Yashar, Ehrlich V. Maximilian. 2020. On the optimal design of place-based policies: A structural evaluation of EU regional transfers. Journal of International Economics, 125. [CrossRef]

- Bourdin, Sebastien. 2019. Does the cohesion policy have the same influence on growth everywhere? A geographically weighted regression approach in Central and Eastern Europe. Economic Geography, 95 (3), 256-287. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, John, Zaleski Janusz, and Mogila Zbigniew. 2022. Measuring the Impact of Regional Development. Policies in Ukraine. A data-based methodology. Final Report of Senior International Experts of the Regional Projects Team of U-LEAD, Available online:http://www.herminonline.net/images/downloads/bradley/2022-Measuring-Impact-RDP-Ukraine_Final_Report_EN.pdf.

- Charasz, Pawel, & Vogler, Jan P. 2021. Does EU funding improve local state capacity? Evidence from Polish municipalities. European Union Politics, 22(3), 446–471. [CrossRef]

- Ciani, Emanuele, de Blasio, Guido. 2015. European structural funds during the crisis: evidence from Southern Italy. IZA Journal of Labor Policy 4. [CrossRef]

- Crepaz, Michele, & Hanegraaff, Marcel. 2022. (Don’t) bite the hand that feeds you: Do critical interest organizations gain less funding in the EU? European Political Science Review, 14(3), 315-332.

- Crescenzi, Riccardo, Di Cataldo, Marco, Giua, Mara. 2020. It’s not about the money. EU funds, local opportunities, and Euroscepticism, Regional Science and Urban Economics, 84. [CrossRef]

- Crucitti, Francesca, Lazarou Joseph Nicholas, Monfort Philippe, and Salotti, Simone (2023). Where does the EU cohesion policy produce its benefits? A model analysis of the international spillovers generated by the policy, Economic Systems. Elsevier.

- Cunico Giovanni, Aivazidou Eirini, and Mollona Edoardo. 2021. Beyond financial proxies in Cohesion Policy inputs' monitoring: A system dynamics approach. Evaluation and Program Planning, 89. [CrossRef]

- Destefanis, Sergio and Di Giacinto, Valter. 2023. EU Structural Funds and GDP per Capita: Spatial VAR Evidence for the European Regions. Bank of Italy Temi di Discussione. 1409. [CrossRef]

- Fidrmuc, Jan, Hulényi Martin, and Zajkowska Olga. 2019. The Elusive Quest for the Holy Grail of an Impact of EU Funds on Regional Growth. CESifo Working Paper, 7989. [CrossRef]

- Florkowski J. Wojciech, and Rakowska Joanna. 2022. Review of Regional Renewable Energy Investment Projects: The Example of EU Cohesion Funds Dispersal. Sustainability, 14(24). [CrossRef]

- Gorzelak, Grzegorz, and Przekop Wiszniewska Ewelina. 2021. European Union Funds in Poland: Sociological, Institutional and Economic Evaluations. Polish Sociological Review, 216(4), 451-472. [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, Christian. 2019. How politics matters for EU funds’ absorption problems – A fuzzy-set analysis. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(2), 188–206. [CrossRef]

- Incaltarau, Christian, Gabriela Carmen Pascariu & Neculai-Cristian Surubaru. 2020. "Evaluating the Determinants of EU Funds Absorption across Old and New Member States - the Role of Administrative Capacity and Political Governance," Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(4), 941-961. [CrossRef]

- Kalfova, Elena. 2019. Factors for adoption of EU funds in Bulgaria, Heliyon. 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Kersan Škabić, Ines, and Tijanić Lela. 2017. Regional absorption capacity of EU funds. Economic Research, 30(1), 1192-1208. [CrossRef]

- Madeira Miguel, Paulo, Vale Mario, and Mora Aliseda Julian. 2021. Smart Specialisation Strategies and Regional Convergence: Spanish Extremadura after a Period of Divergence. Economies, 9(4), 138. [CrossRef]

- Lutringer, Christine. 2023. “The Puzzle of ‘Unspent’ Funds in Italy’s European Social Fund”, International Development Policy Revue internationale de politique de développement. [CrossRef]

- Maras, Marin. 2022. The spillover effect of European Union funds between the regions of the new European Union members. Croatian Review of Economic, Business and Social Statistics (CREBSS), 8(1), 58-22. [CrossRef]

- Marcu. Laura, Kandzija Tomislav, and Dorotic Jelena. 2020. EU Funds Absorption: Case of Romania. Postmodern Openings, 11(4), 41-63. [CrossRef]

- Medve-Bálint, Gergő, Šćepanović, Vera. 2020. EU funds, state capacity and the development of transnational industrial policies in Europe’s Eastern periphery. Review of International Political Economy. 27(5). [CrossRef]

- Melecký, Lukáš. 2018. The main achievements of the EU structural funds 2007–2013 in the EU member states: efficiency analysis of transport sector.Equilibrium. Quarter-ly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy. 13(2). 285–306. [CrossRef]

- Mendez, Carlos, and Bachtler John. 2022. The quality of government and administrative performance: explaining Cohesion Policy compliance, absorption and achievements across EU regions, Regional Studies. [CrossRef]

- Muraközy, Balázs, Telegdy, Álmos. 2023. The effects of EU-funded enterprise grants on firms and workers. Journal of Comparative Economics. 51(1), 216-234. [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, Phillip, Varga Janos, and in ‘t Veld Jan. 2021. Quantifying spillovers of NextGenerationEU investment. European Economy Discussion Papers, 144.

- Piątkowski, J. Marcin. 2020. Results of SME Investment Activities: A Comparative Analysis among Enterprises Using and Not Using EU Subsidies in Poland. Administrative Sciences, 10 (1), 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Picek, Oliver. 2020. Spillover effects from next generation EU. Intereconomics, 55(5), 325–331. [CrossRef]

- Pîrvu, Ramona, Drăgan Cristianu, Axinte Gheorghe, Dinulescu Sorin, Lupăncescu Mihaela, and Găină Andra. 2019. The Impact of the Implementation of Cohesion Policy on the Sustainable Development of EU Countries. Sustainability, 11(15), 4173. [CrossRef]

- Roeger, Werner, Varga, Janos, and in’t Veld Jan. 2022. The QUEST III R&D Model. In: Akcigit, U., Benedetti Fasil, C., Impullitti, G., Licandro, O., Sanchez-Martinez, M. (eds) Macroeconomic Modelling of R&D and Innovation Policies. International Economic Association Series. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Sakkas, S., Crucitti, F., Conte, A., & Salotti, S. (2021). The 2020 territorial impact of Covid-19 in the EU: A RHOMOLO update. Territorial Development Insights Series, JRC125536. European Commission. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:ipt:iptwpa:jrc125536.

- Surubaru, Cristian Neculai. 2021. European funds in Central and Eastern Europe: drivers of change or mere funding transfers? Evaluating the impact of European aid on national and local development in Bulgaria and Romania, European Politics and Society, 22:2, 203-221. [CrossRef]

- Szlachta, Jacek. 2004. The role of the structural funds and cohesion fund in the stimulation of sustained economic growth in Poland, TIGER Working Paper Series, 69, Transformation, Integration and Globalization Economic Research (TIGER), Warsaw. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/140721.

- Šelebaj, Domagoj, Bule, Matej. 2021. Effects of grants from EU funds on business performance of non-financial corporations in Croatia. Public Sector Economics, 45(2), 177-207. [CrossRef]

- Šostar, Marko. 2021a. Utilization of EU funds: Impact on development // Tenth international scientific conference Employment, education and entrepreneurship / Nikitovic, Zorana ; Radovic-Markovic, Mirjana ; Vujicic, Sladjana (ur.). Belgrade, 2021. str. 196-201. Available online: https://www.bib.irb.hr/1262597.

- Šostar, Marko. 2021b. Real Impact of EU Funding - Quality Versus Quantity // Economic and Social Development / Aleksic, Ana ; Ruzic, Vlatka ; Baracskaioltan, Zoltan (ur.). Varaždin, Hrvatska, 2021. str. 99-105. Available online: https://www.bib.irb.hr/1112444.

- Šostar, Marko. 2020. Fondovi EU: Financijske korekcije kao provedbeni izazov // 7th International Conference "Vallis Aurea" / Katalinić, Branko (ur.). Požega, Hrvatska: Veleučilište u Požegi, 2020. str. 593-601. Available online: https://www.bib.irb.hr/1110050.

- Šostar, Marko, and Marukić Ana. 2017. Challenges of Public Procurement in EU Funded Projects. Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 22 (2), 99-113. Available online: https://www.bib.irb.hr/933848.

- Terracciano, Brian, and Graziano, R. Paolo. 2016. EU Cohesion Policy implementation and administrative capacities: Insights from Italian regions. Regional & Federal Studies, 26(3), 293–320. [CrossRef]

- Țigănașu, Ramona, Incaltarau Cristian, and Pascariu Gabriela Carmen. 2018. Administrative Capacity, Structural Funds Absorption and Development. Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries. Romanian Journal of European Affairs, 18(1), Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3296925.

- Van Wolleghem, Georges Pierre. 2022. Does administrative capacity matter? The absorption of the European Fund for the integration of migrants. Policy Studies, 43(4), 640-658. [CrossRef]

- Vukašina, Martina, Kersan-Škabić Ines, and Orlić Edvard. 2022. Impact of European structural and investment funds absorption on the regional development in the EU-12 (new member states). Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy, 17(4), 857–880. [CrossRef]

- Walesiak, Marek, Dehnel Grazyna. 2023. Measurement of Social Cohesion in Poland’s NUTS2 Regions in the Period 2010–2019 by Applying Dynamic Relative Taxonomy to Interval-Valued Data. Sustainability, 15(4). [CrossRef]

- Wolleghem, Van Georges Pierre. 2020. Does administrative capacity matter? The absorption of the European Fund for the integration of migrants, Policy Studies. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Descriptive data by scales and by countries of origin of the respondents.

Table 1.

Descriptive data by scales and by countries of origin of the respondents.

| |

Country |

Number |

Arithmetic mean |

Standard deviation |

Min |

Max |

| Education at all levels in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

Poland |

51 |

17,4118 |

1,73409 |

14,00 |

20,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

5,8065 |

2,04730 |

4,00 |

15,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

6,3871 |

1,94477 |

4,00 |

12,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

7,5217 |

2,96850 |

4,00 |

19,00 |

| Total |

244 |

8,8648 |

4,98827 |

4,00 |

20,00 |

| Awareness of funding opportunities from EU funds |

Poland |

51 |

13,2353 |

1,64424 |

9,00 |

15,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

4,9516 |

1,55160 |

3,00 |

11,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

5,9516 |

2,47894 |

3,00 |

15,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

6,6087 |

2,00893 |

3,00 |

13,00 |

| Total |

244 |

7,4057 |

3,63614 |

3,00 |

15,00 |

| Creativity of key individuals in preparing projects for EU funds |

Poland |

51 |

17,8235 |

1,51929 |

15,00 |

20,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

6,8710 |

1,47641 |

4,00 |

9,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

7,0323 |

1,81042 |

4,00 |

12,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

8,8116 |

2,98661 |

4,00 |

18,00 |

| Total |

244 |

9,7500 |

4,71917 |

4,00 |

20,00 |

| Team collaboration in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

Poland |

51 |

9,8235 |

,38501 |

9,00 |

10,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

3,2742 |

,77183 |

2,00 |

4,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

3,5161 |

1,06728 |

2,00 |

7,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

4,6377 |

1,50461 |

2,00 |

8,00 |

| Total |

244 |

5,0902 |

2,70803 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Motivation of key individuals in preparing projects for EU funds |

Poland |

51 |

16,8235 |

2,38081 |

13,00 |

20,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

6,5806 |

1,81567 |

4,00 |

12,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

6,8226 |

2,04478 |

4,00 |

13,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

9,4493 |

2,79988 |

5,00 |

18,00 |

| Total |

244 |

9,5943 |

4,52648 |

4,00 |

20,00 |

Financial capacities for co-financing

projects from EU funds

|

Poland |

51 |

9,2353 |

1,12407 |

7,00 |

10,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

3,2903 |

,83739 |

2,00 |

5,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

3,1935 |

,80650 |

2,00 |

4,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

3,5362 |

1,44079 |

2,00 |

9,00 |

| Total |

244 |

4,5779 |

2,63681 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

Alignment of strategic documents with

development needs

|

Poland |

51 |

9,6471 |

,48264 |

9,00 |

10,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

3,0484 |

,85751 |

2,00 |

5,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

3,4355 |

1,31350 |

2,00 |

7,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

4,6957 |

1,83355 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Total |

244 |

4,9918 |

2,78590 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

Level of technological readiness for the

implementation of projects from EU funds

|

Poland |

51 |

9,1176 |

,84017 |

7,00 |

10,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

3,2258 |

,87627 |

2,00 |

4,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

3,5806 |

1,34954 |

2,00 |

7,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

4,4638 |

1,59576 |

2,00 |

9,00 |

| Total |

244 |

4,8975 |

2,54057 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Number of prepared projects for EU funds |

Poland |

51 |

4,5294 |

,61165 |

3,00 |

5,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

1,4677 |

,50303 |

1,00 |

2,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

1,4194 |

,49748 |

1,00 |

2,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

1,3623 |

,83966 |

1,00 |

5,00 |

| Total |

244 |

2,0656 |

1,41850 |

1,00 |

5,00 |

| Contracted funds rate from EU funds |

Poland |

51 |

9,2941 |

,75615 |

8,00 |

10,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

3,3387 |

,90433 |

2,00 |

6,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

3,4194 |

,73659 |

2,00 |

5,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

3,4348 |

1,49979 |

2,00 |

9,00 |

| Total |

244 |

4,6311 |

2,61902 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Number of successfully implemented projects from EU funds |

Poland |

51 |

13,7647 |

1,22618 |

10,00 |

15,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

4,9355 |

1,37746 |

3,00 |

9,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

4,9839 |

1,16636 |

3,00 |

8,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

6,6812 |

2,28481 |

3,00 |

12,00 |

| Total |

244 |

7,2869 |

3,77664 |

3,00 |

15,00 |

| Regional competitiveness index |

Poland |

51 |

27,1176 |

2,24185 |

24,00 |

30,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

10,8548 |

1,99052 |

6,00 |

14,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

11,5323 |

4,76228 |

8,00 |

30,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

13,0435 |

5,85972 |

6,00 |

28,00 |

| Total |

244 |

15,0451 |

7,52896 |

6,00 |

30,00 |

| Level of financial dependence on centralized state funds |

Poland |

51 |

25,9412 |

2,23080 |

23,00 |

30,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

10,2097 |

2,33391 |

6,00 |

18,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

11,1129 |

2,48342 |

7,00 |

19,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

13,7536 |

4,83372 |

6,00 |

24,00 |

| Total |

244 |

14,7295 |

6,75867 |

6,00 |

30,00 |

| Level of personal consumption |

Poland |

51 |

8,5882 |

,98339 |

7,00 |

10,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

3,3871 |

,91176 |

2,00 |

6,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

3,8387 |

,63229 |

2,00 |

5,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

5,0870 |

1,89224 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Total |

244 |

5,0697 |

2,28415 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Level of state consumption |

Poland |

51 |

5,2353 |

,95054 |

4,00 |

7,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

3,3065 |

1,12481 |

2,00 |

8,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

3,6129 |

1,61301 |

2,00 |

9,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

4,3478 |

2,31254 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Total |

244 |

4,0820 |

1,77820 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Number of investments |

Poland |

51 |

9,1765 |

,79261 |

8,00 |

10,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

3,3226 |

,84493 |

2,00 |

4,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

3,8387 |

,70580 |

2,00 |

5,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

2,8696 |

1,38174 |

2,00 |

9,00 |

| Total |

244 |

4,5492 |

2,60295 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Unemployment rate |

Poland |

51 |

5,8824 |

,90878 |

4,00 |

8,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

5,5161 |

,97075 |

2,00 |

6,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

5,2258 |

,87627 |

2,00 |

6,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

5,6522 |

1,23462 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Total |

244 |

5,5574 |

1,03875 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Population |

Poland |

51 |

7,9412 |

,64535 |

7,00 |

9,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

3,9194 |

,87400 |

2,00 |

6,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

3,9516 |

1,01509 |

2,00 |

7,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

4,0435 |

1,91307 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Total |

244 |

4,8033 |

2,04331 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Level of competitiveness |

Poland |

51 |

9,0588 |

,73244 |

8,00 |

10,00 |

| Slovenia |

62 |

3,6129 |

,66171 |

2,00 |

5,00 |

| Hungary |

62 |

3,6290 |

,90958 |

2,00 |

6,00 |

| Croatia |

69 |

2,8406 |

1,38928 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

| Total |

244 |

4,5369 |

2,55045 |

2,00 |

10,00 |

Table 2.

ANOVA results for all scales within the survey according to the amounts of respondent scores from Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary, and Poland.

Table 2.

ANOVA results for all scales within the survey according to the amounts of respondent scores from Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary, and Poland.

| |

|

Sum of squared deviations |

df |

Mean squared deviation |

F |

Sig. |

| Education at all levels in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

Between groups |

4810,579 |

3 |

1603,526 |

311,375 |

,000 |

| Within groups |

1235,957 |

240 |

5,150 |

|

|

| Total |

6046,537 |

243 |

|

|

|

Awareness of financing opportunities from EU funds

|

Between groups |

2281,511 |

3 |

760,504 |

195,981 |

,000 |

| Within groups |

931,321 |

240 |

3,881 |

|

|

| Total |

3212,832 |

243 |

|

|

|

| Creativity of key people in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

Between groups |

4356,884 |

3 |

1452,295 |

330,422 |

,000 |

| Within groups |

1054,866 |

240 |

4,395 |

|

|

| Total |

5411,750 |

243 |

|

|

|

| Team collaboration in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

Between groups |

1514,840 |

3 |

504,947 |

453,585 |

,000 |

| Within groups |

267,176 |

240 |

1,113 |

|

|

| Total |

1782,016 |

243 |

|

|

|

| Motivation of key people in the preparation of projects for EU funds |

Between groups |

3706,203 |

3 |

1235,401 |

232,979 |

,000 |

| Within groups |

1272,629 |

240 |

5,303 |

|

|

| Total |

4978,832 |

243 |

|

|

|

| Financial capacities for co-financing projects from EU funds |

Between groups |

1402,733 |

3 |

467,578 |

391,295 |

,000 |

| Within groups |

286,788 |

240 |

1,195 |

|

|

| Total |

1689,520 |

243 |

|

|

|

| Alignment of strategic documents with development needs |

Between groups |

1495,631 |

3 |

498,544 |

306,519 |

,000 |

| Within groups |

390,353 |

240 |

1,626 |

|

|

| Total |

1885,984 |

243 |

|

|

|

| Level of technological readiness for implementation of projects from EU funds |

Between groups |

1202,050 |

3 |

400,683 |

262,464 |

,000 |

| Within groups |

366,389 |

240 |