1. Introduction

The main challenge faced by the administration of hydrophobic anti-cancer drugs is their low solubility resulting in poor bio-distribution [

1,

2]. Encapsulation into nano-carriers can enhance the drugs’ selective delivery to their pharmacological site and decrease side effects [

3]. So far, different types of nano-carriers have been studied for targeted delivery of developed drugs [

4]. Polymeric nanomaterials offer certain advantages over other nano-carriers in terms of stability and modulation of drug release via controlling polymer biodegradation [

5]. Polymeric nanomicelles containing both hydrophilic and hydrophobic moieties have the ability to self-assemble. Their properties can be precisely controlled and tailored for many applications. Also, their balance between hydrophobic/hydrophilic ratio can be controlled, which is a prerequisite for the self-assembly process [

6]. The amphiphilic nature of the block copolymers is an important characteristic for the drug delivery process [

7].

According to previous observations, block copolymers enable the production of nanoscale materials [

8,

9], and provide the ability to engineer various nanostructures [

10,

11]. Block copolymers are macromolecules that contain two or more chemically distinct chains covalently bonded to each other for specific purposes [

12]. The mixing entropy of block copolymers per unit volume is very small [

13], which makes their thermodynamics discordant with other blocks [

14]. These copolymers can be efficiently functionalized and used as potential drug delivery systems [

15]. Furthermore, copolymers can be engineered to control drug loading and release of drugs [

16]. Block copolymers have two different types of drug-loading strategies [

17]. In the first strategy, the drug is loaded into nanomicelles via covalent bonds between the drugs and the nanocarriers, which must be cleaved [

18]. The second strategy is the most prevalent, in which the drug is entrapped inside micelles via physical interactions [

19]. Here, therapeutic molecules are located within the core or shell of nanomicelles and release often occurs via diffusion [

20]. In fact, nanomicelles produced by the first and second strategies are structurally similar but their stability attributes are different [

21]. The stability of nanomicelles plays an important role in the safety and efficacy of these formulations [

22].

This study was conducted to understand the biochemical behavior of PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG copolymers using in silico

and in vitro approaches [

23]. Herein, we employed molecular dynamics (MD) and free energy calculation to compare the dynamics and thermodynamics of understudied systems and compare them based on their ability to interact with the 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (POPC) membrane. Also, curcumin-loaded PLA–PEG–PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG were investigated for their potential to deliver curcumin to MCF-7 cells. A variety of physicochemical properties, including Zeta potential, size, and morphology, were assessed for PLA–PEG–PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG copolymers. In addition to measuring the loading capacity, we also assessed the release of curcumin from curcumin-loaded copolymers. The anticancer potential of curcumin-loaded copolymers was analyzed quantitatively using MTT, and the expression levels of Bcl-2, Bax, and hTERT genes were evaluated using RT-qPCR.

2. Materials and methods

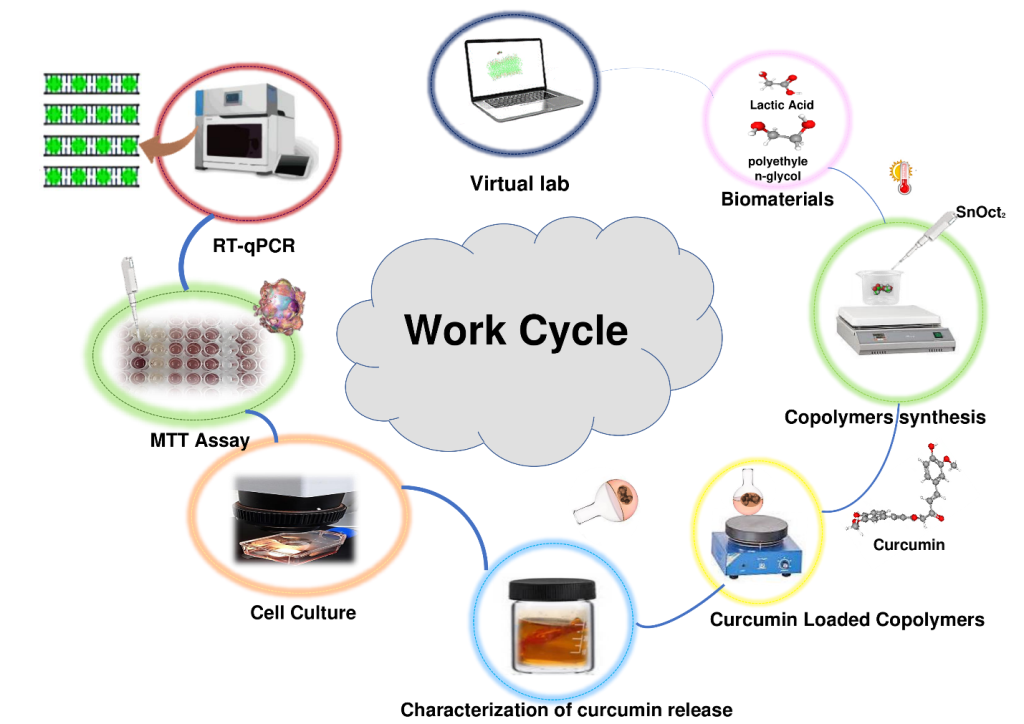

Work cycle utilized in this study included computational analysis of expected conformational behavior of copolymers, synthesis of copolymers, loading copolymers with curcumin, characterization of curcumin release

in vitro, analysis of the effects of the curcumin-loaded polymers on viability of the MCF-7 cancer cells, and analysis of the effect of the treatment the MCF-7 cancer cells with the curcumin-loaded polymers on the expression several target genes. This work cycle is schematically represented in

Figure 1.

2.1. Force field

The morphology of the bilayer membrane and nanomicelles were constructed and generated by the CHARMM36. The CHARMM36 force field was applied to build and assess the forces and describe the energy landscape between atoms within systems [

24,

25].

2.2. Copolymers and biomembrane preparation

The structures of PLA and PEG monomers were downloaded from PubChem in SDF format (

Table 1). The downloaded monomers’ structures were optimized and linked together based on the planned design via HyperChem (v8.0.3) to form PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG copolymer molecules.

In the next step, the CHARMM-GUI server was utilized to generate a biomembrane with desired lipid compositions. This server is an online server owned by LEHIGH University.[

26] The CHARMM-GUI server possesses the capability to perform atomic-level characterization of both small molecules and large biomolecules. In the present study, we chose the pure 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (POPC) bilayer. During biomembrane preparation, rectangular box type was selected. The length of the Z-axis was adjusted in accordance with the hydration number, which specifies 33 water molecules per lipid molecule. The number of lipids was set to 64 on the upper and lower leaflet (overall 128 POPC molecules), and a surface area value of 63 Å was chosen. In the ionization step, 0.15 M NaCl was added to our system [

27]. For membrane parametrization, force field CHARMM36 was selected. For the purpose of assessing their potential interaction with the target bilayer, the copolymers were positioned within a proximity of 5 Å from the membrane [

28].

2.3. MD simulations

MD is a useful approach for investigating the effect of solvent molecules on macromolecule structure and stability factors to obtain properties of the biomolecular systems, namely dipolar moment, density, conductivity, and diverse thermodynamic parameters, including entropies and interaction energies (Vandevals and GIBBS).[

29] In this study, we conducted equilibration of the systems using the NVT (N = number of atoms, V = volume, and T = temperature) and NPT (P = pressure) ensembles. We utilized the CUDA-compiled GROMACS v2022.2 [

30] software on Ubuntu v22.04 for this purpose. The temperature was maintained at approximately 310 K using the V-rescale model, with a time constant of 2 fs [

31]. To control the pressure, we employed the Parrinello-Rahman algorithm with a compressibility value of 4.0 × 10

-5 bar

-1 . Additionally, semi-isotropic coupling was applied to ensure a tensionless lipid bilayer. During the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, the LJ potentials were adjusted to zero between a cutoff distance of 1.2 nm and rshift = 0.9 nm. The pair list was refreshed every 20 steps to ensure accurate and efficient calculations [

32]. NVT and NPT steps were performed for 500 ps and 5 ns, respectively. In the production step, the configurations were sampled at every 100 ps. Finally, at the production step, all systems were simulated for 200 ns in TIP3P solvent [

33]. After MD simulation, some functions like root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), solvent accessible surface area (SASA), radial distribution function (RDF), and mean square displacement (MSD) were extracted from the output trajectory files [

34,

35].

2.4. Binding free energy analysis

The molecular mechanics–Poisson Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA) method was applied to compute the binding energy and impact of conformational changes on its value [

36]. Here, the binding free energy was calculated using g_mmpbsa during the 200 ns of the molecular dynamics simulation [

37]. During this step, the accessible surface area (SASA) model was utilized for apolar solvation energy calculation. The free energy computations of the POPC-copolymers binding are measured via the following Equation (1):

where,

is the total free energy of the POPC−Copolymer and

and

denote total free energies of the POPC and copolymer in the solvent, respectively. Furthermore, the free energy for each individual entity can be given (2):

is the free energy of solvation, and T and S are the temperature and entropy, respectively.

is the average molecular mechanics potential energy in a vacuum, which is given as an Equation (3):

where

is Electrostatic and

is van der Waals interactions between POPC and copolymers, and

is bonded interactions consisting of angle, bond, dihedral and unfit interactions.

is the nonbonded interactions that include both van der Waals and electrostatic interactions. Furthermore, in the single trajectory method, the conformation of membrane and copolymers in the bound and unbound forms are assumed to be the same. Therefore,

is taken as zero. And also

is calculated by Equation (4):

where

are determined by polar solvation energy and SASA energy, respectively.

2.5. Materials

Polyethylene glycol (PEG Mn = 4000), L-lactic acid (14.7kDa), N, N0-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide, stannous 2-ethyl-hexanoate (SnOct2), 5-diphenyl -2-H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT), diethyl ether, dichloromethane, acetone, and ethanol were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich. MCF-7 cell line was provided by the Pasteur Institute of Iran.

2.6. Synthesis of PLA–PEG–PLA copolymer

The PLA–PEG–PLA block copolymer was synthesized from d, l-lactide with mPEG as the initial molecule and stannous octoate as the catalyst using a ring-opening polymerization (ROP) [

38]. To begin polymerization, mPEG (1 mg), lactide (6 mg), and 0.05% (w/w) stannous octoate were heated to 130 ℃ in dichloromethane on continuous stirring. After 24 h, the produced polymer dissolved in chloroform, and was cooled to room temperature. Then, it was precipitated in diethyl ether. In addition, for additional purification, the product was precipitated in distilled water three times. To dry the final products, the resulting polymer was first kept at room temperature for 24 h. Afterward, they were completely dried in a freeze dryer for 48 h at -60° C. The resulting product was a white powder, which was characterized and used for further studies. The final structure of the polymer was characterized by proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (

1H-NMR) in CDCL

3 [

39] at 500 MHz (Bruker Ac 500, Germany) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR; Nicolet 550 A, USA). Also, the surface charge and particle size of the PLA-PEG-PLA were determined by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS; Malvern Zeta sizer 3000HS, Malvern, UK). Additionally, the surface properties of block copolymers were determined using water contact angle (SDC100, Minder Hightech, China) and scanning electron microscope (SEM; JSM-5600LV, Jeol, Japan).

2.7. Synthesis of PEG–PLA–PEG copolymer

As in the previous section, the synthesis of PEG–PLA–PEG copolymer was realized using ROP. mPEG (6 mg) was dissolved with lactide (1 mg) and 0.05% (w/w) stannous octoate in dichloromethane. The mixture was refluxed by continuous stirring at 110 ◦C for 18 h. Following solvent removal under vacuum, the resultant product was purified by dissolving in toluene and precipitating in cold ethyl ether (−20° C) and then in distillate water for three times to obtain a purified product. Then, the copolymer was lyophilized for 48 h using conditions similar to the PLA-PEG-PLA copolymer. Similar to the previous section, the structure and surface characteristics of the synthesized copolymer were examined by FT-IR, NMR, DLS, and SEM.

2.8. Measurement of curcumin encapsulation efficiency

To measure curcumin encapsulation efficiency in copolymers, 10 mg of freeze-dried PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG were dissolved in 10 ml acetone: water mixture (30:70 v/v) containing 1 mg of curcumin. The resulting solution was stirred for 30 min and then centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min. Then, the supernatant was passed through a filter (14 kDa) and the curcumin–copolymer solution was achieved. Further, the freeze-drying process was implemented to prepare powders from the output of this step. Thereafter, the amount of loaded curcumin and encapsulation efficiency (EE) were calculated by measuring the absorbance of curcumin at 425 nm [

40]. The following Equations (5) and (6), were used for calculating loading efficiency and encapsulation efficiency, respectively:

The drug loading and encapsulation were also calculated in different weight ratios of drug and copolymer (CUR: Copolymer; 1:10, 1:20, and 1:50).

2.9. In vitro release study

The dialysis bag diffusion technique was applied to study the curcumin release behavior from the copolymers. The freeze-dried curcumin-copolymers with curcumin: copolymer ratio of 1:10, 1:20, and 1:50 were analyzed for release studies. Briefly, the samples containing 20 mg of curcumin-loaded block copolymers were poured into a dialysis bag (Mw 14 kDa). The dialysis bag was then suspended in 40 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.01 M, pH 7.4) and kept in an incubator shaking mixer (Taitec, BR-42FL, Japan) at 100 rpm and 37° C. Samples were removed from the receptor medium at time intervals of 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 100 h. They were then replaced with the same volumes of fresh PBS. The released curcumin value was quantified using its absorbance at 425 nm using a UV/Vis spectrophotometer.

2.10. Cell culture

MCF-7 cells were cultured at 37℃ in a humidified atmosphere (95% air, 5% CO2) in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% (v/v) FBS, 100 gmL-1 streptomycin, 100 UmL-1 penicillin, 2 mM L-1 glutamine, and 1% non-essential amino acid.

2.11. In vitro cell viability assay

MCF-7, breast cancer cells were employed to evaluate the cytotoxicity of block copolymers and those containing curcumin using MTT essay. MCF-7 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 10

3 cells per well) with 150 µl/well RPMI medium containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were incubated for one day at 37

°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2, and 95% humidity. In all cellular assays, the cells were treated with different concentrations (0- 60 µM) of free curcumin, PLA-PEG-PLA, PEG-PLA-PEG, curcumin-PLA-PEG-PLA, and PEG-PLA-PEG-curcumin, for 48 h. PBS-treated cells were taken as control (cnt). Percent cell death was calculated by following Equation (7) and the IC50 values curcumin, curcumin-PLA-PEG-PLA, and curcumin-PEG-PLA-PEG were determined.

2.12. Gene expression studies

MCF-7 cells were cultured in six-well plates for 24 hours. Thereafter, the cells were treated with free curcumin and copolymers-formulated curcumin at their IC

50 concentrations. Control cells were treated with PBS. For gene expression analysis, the cells were harvested after 48 hours of treatment. Total RNA was extracted at each time point utilizing the PARS RNA extraction kit (Pars-Tous, Mashhad, Iran). RNA concentration and purity were quantified using a UV-vis spectrophotometer (NanoDrop

TM One

C, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). cDNA synthesis was performed with the PARS cDNA synthesis kit (Pars-Tous, Mashhad, Iran) using the manufacturer’s protocol. To examine the expression level of Bax, Bcl

2, and hTERT, the primers listed in

Table 2 were used. Each PCR reaction contained 2 µL of cDNA, 2 µL of primers, 6 µL DEPC treated water, and 10 µL Amplicon SYBR Green master mix (Ampliqon A/S, Odense, Denmark). The Rotor-Gene 6000 Real-Time PCR device (Corbett Research, Hilden, Germany) was utilized for gene expression studies. The cycle threshold (Ct) values for each gene were normalized using the Ct value of GAPDH. The relative expression of the genes was quantified by using the 2

-ΔΔCt method.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

The statistical difference between the quantitative data such as contact angles, MTT assay, and gene expression was determined using Analyses of variance (one-way ANOVA). p < 0.05 was considered significant when comparing the means. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), was used for statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary molecular dynamics analysis

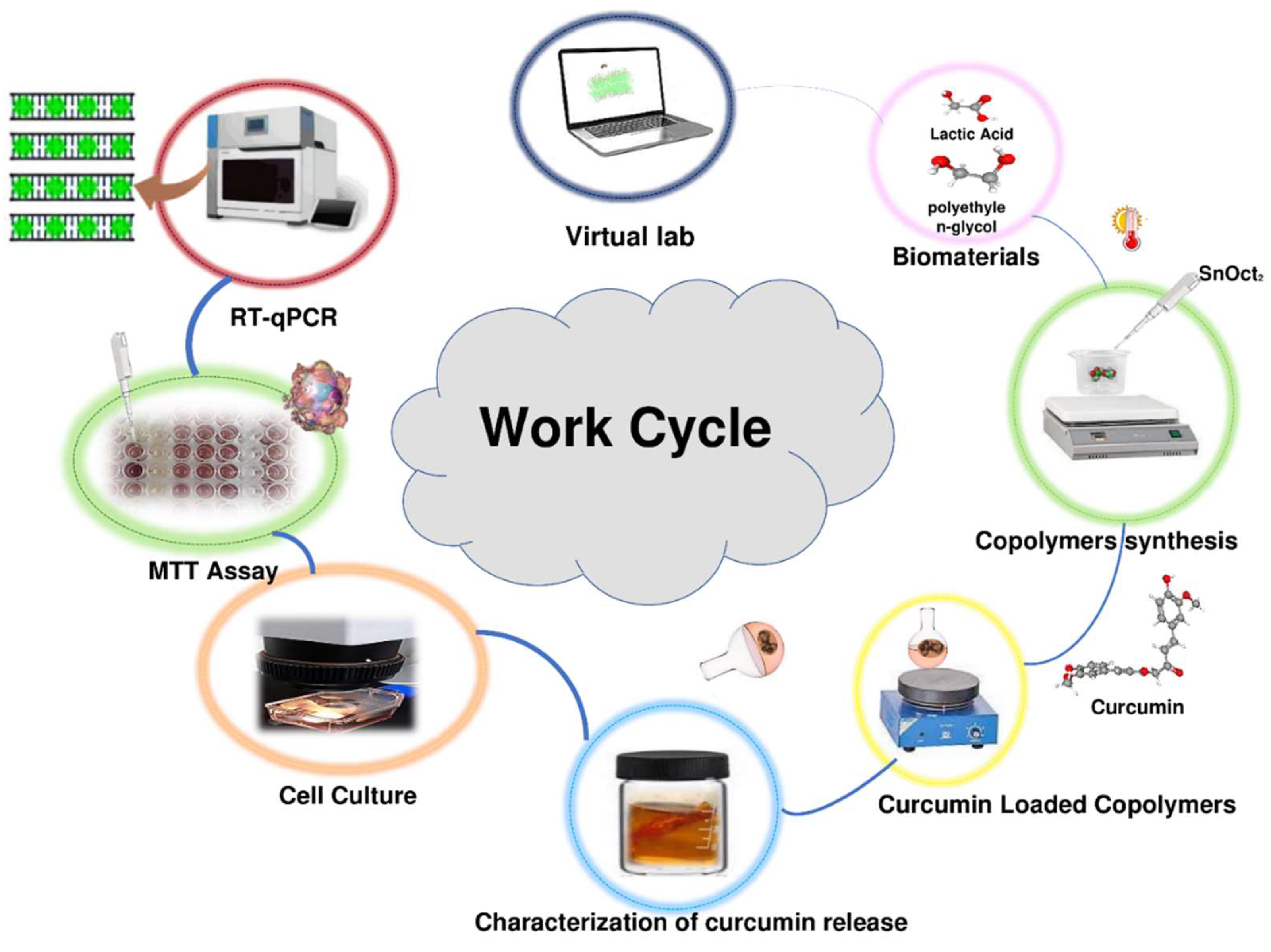

During 200 ns simulations, we measured the RMSD to determine the conformational changes and equilibration of the block copolymers (

Figure 2). As a result, there is a smaller RMSD for PEG-PLA-PEG than PLA-PEG-PLA. However, there was no significant difference in RMSD values between the two block copolymers, and the conformations of copolymers have not changed noticeably. Furthermore, RMSD averages for PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG were 0.17634 and 0.168796 nm, respectively.

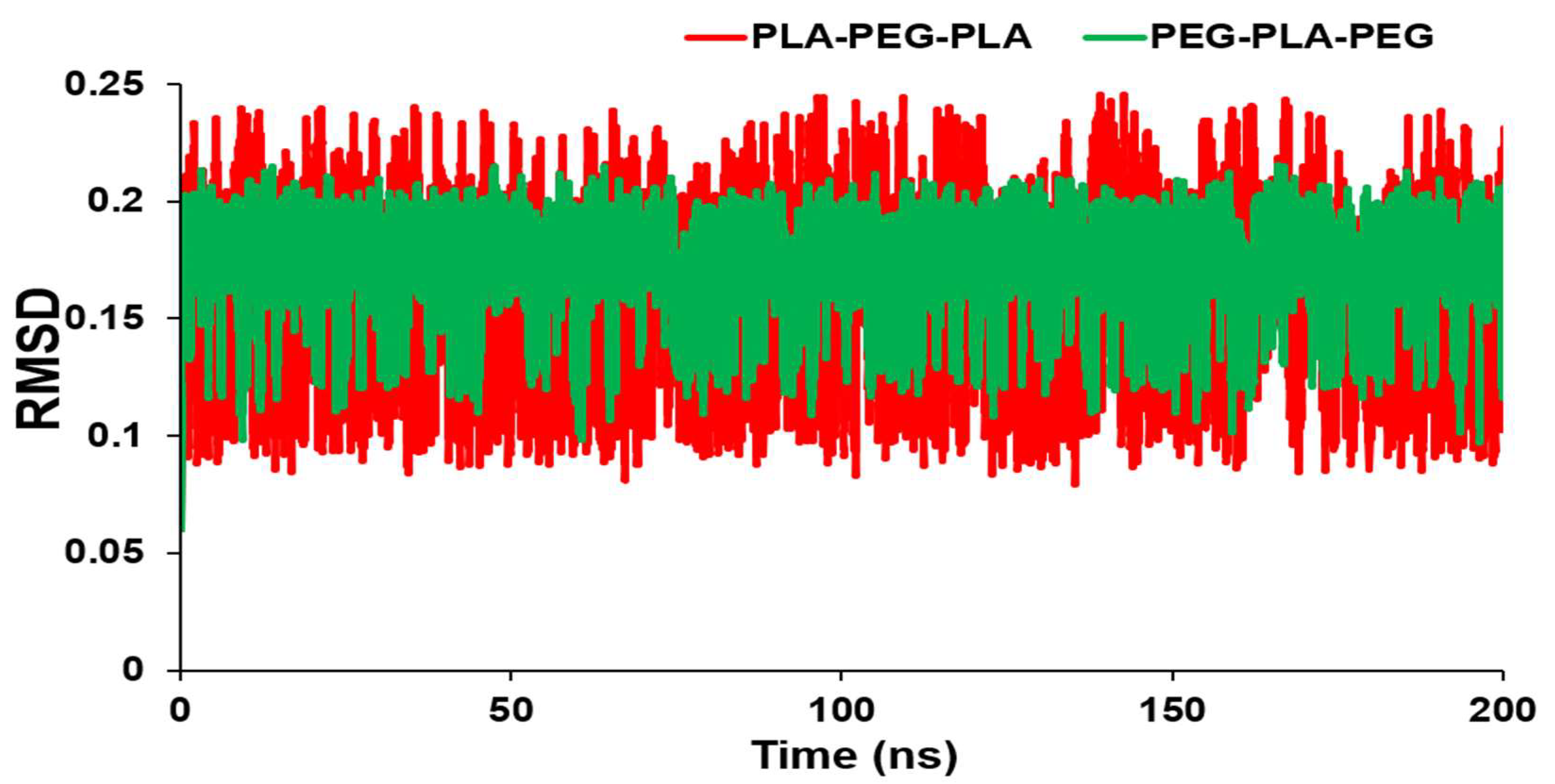

A further significant measurement is the RMSF value, which we calculated during 200 ns of molecular dynamics simulation. The RMSF is the calculation of the average fluctuation at any single atom. The atoms’ flexibility or mobility is estimated via RMSF values to determine the atomic local changes of each block copolymer. The comparative investigation of RMSF values displays that PLA-PEG-PLA fluctuated between 0.14- 0.18 nm while the PEG-PLA-PEG value was between 0.05-0.15 nm (

Figure 3).

3.2. Prediction of block copolymer properties

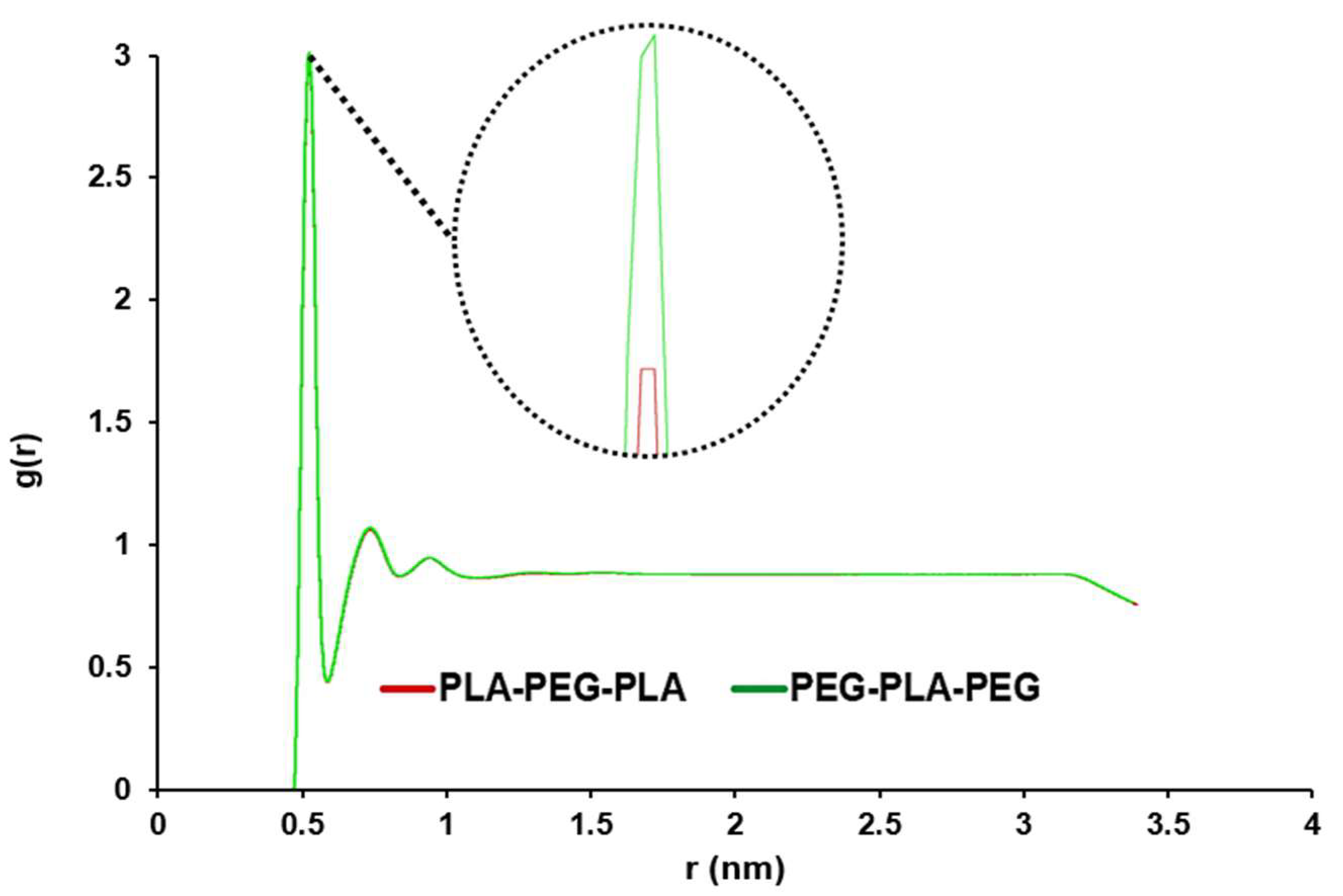

For the analysis of water penetration into the POPC membrane, RDF was enforced. The highest peak corresponds to the maximum value of the density variation from the reference of water molecules at that distance. As seen in

Figure 4, this peak for copolymers is close and very sharp at 0.515 nm, this peak shows the distance where the most water molecules are available. A smaller distance and a larger g (r) indicated more penetration of water into the membrane.

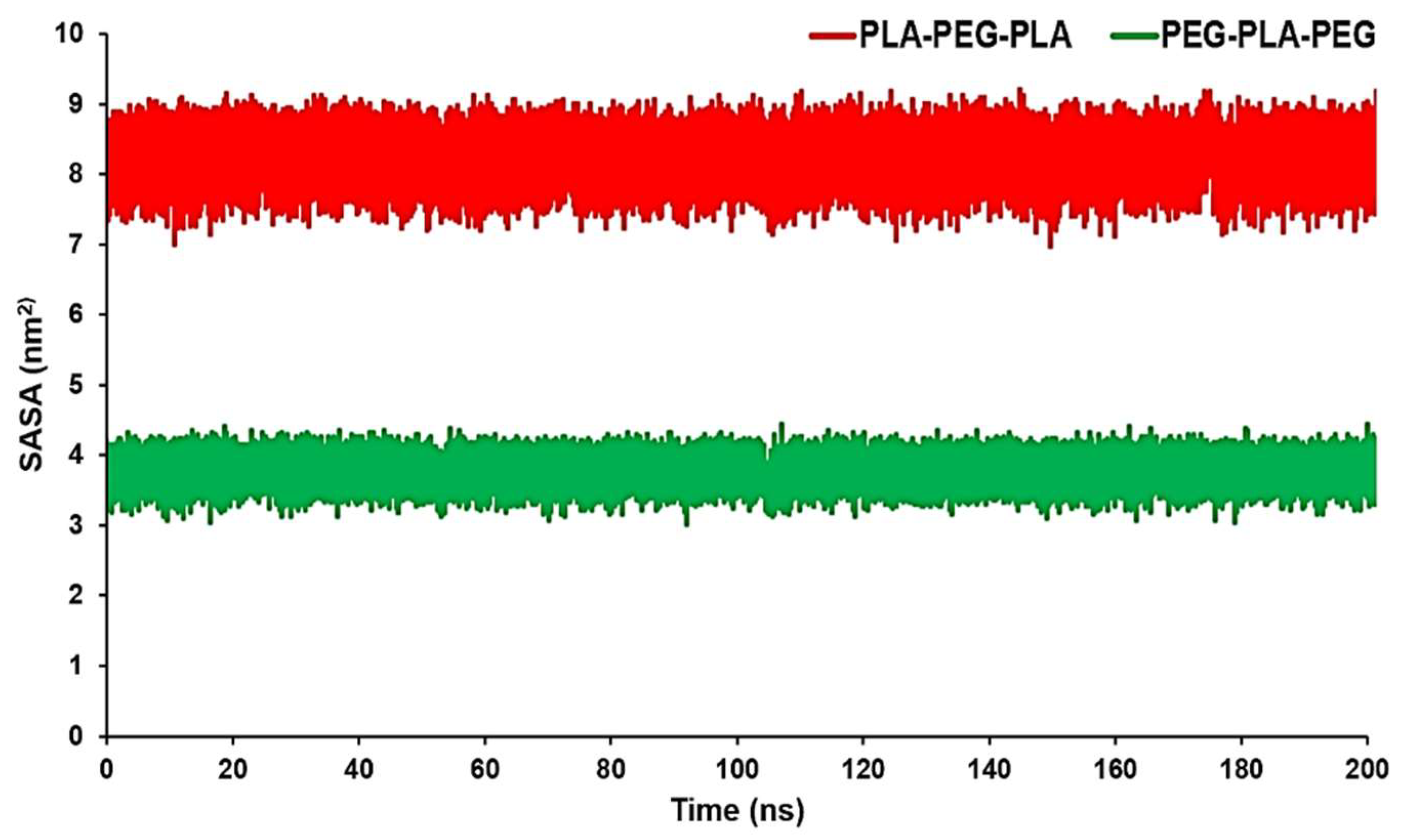

SASA can measure the proportion of the copolymers surface that can be accessed by the water molecules. This data can confirm RDF results conducted by the MD trajectory. The average SASA amount for PLA-PEG-PLA was 8.0923 nm

2, while the average SASA amount for PEG-PLA-PEG was 3.7654 nm

2. From

Figure 5, we can see that PLA-PEG-PLA had higher SASA values over a span of 200 ns.

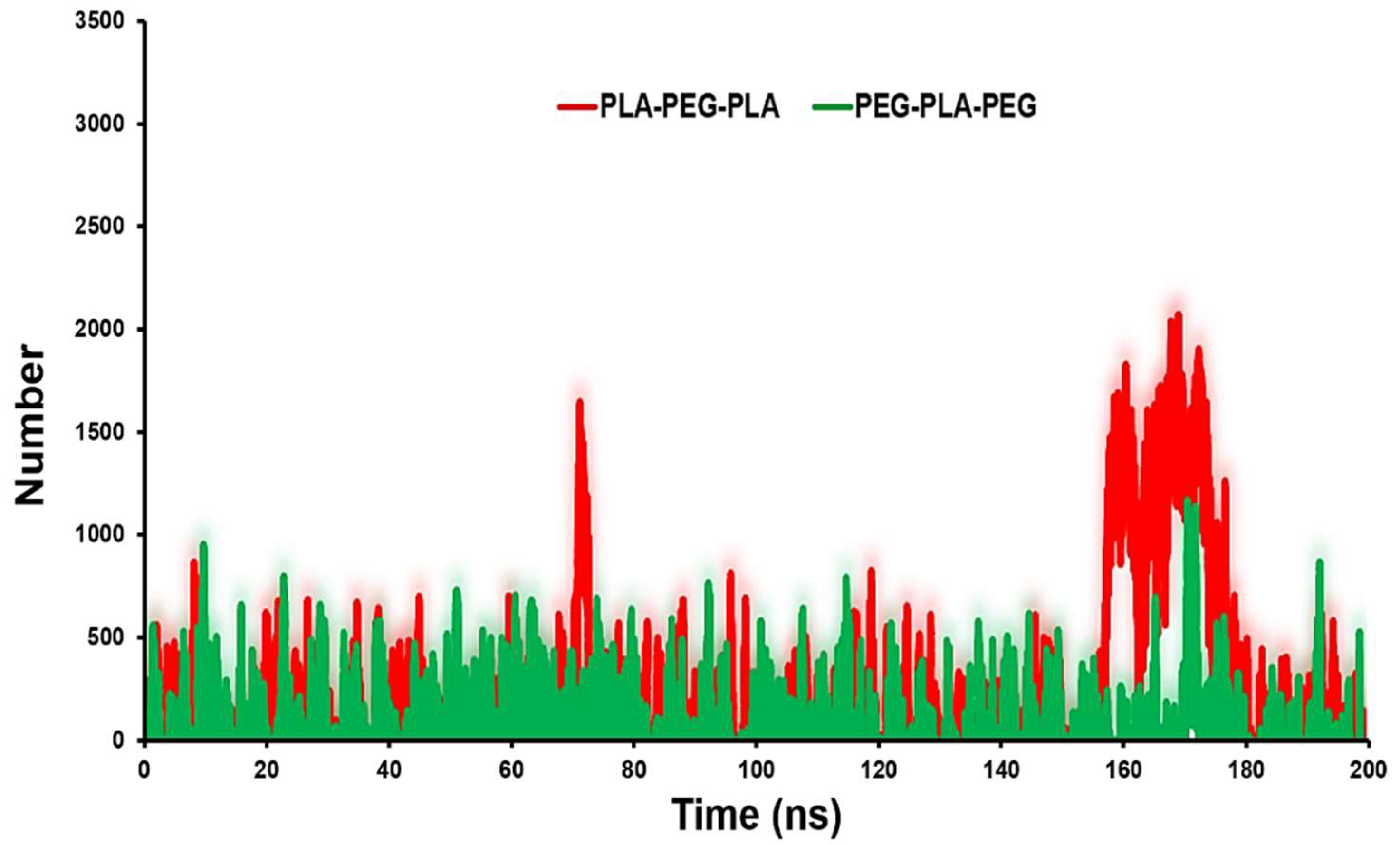

The contact number of copolymers with POPC can reflect the surface physicochemical properties of copolymers on their probable localization.

Figure 6 shows that PLA-PEG-PLA has more contacts with the POPC. The average number of contacts between PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG with membrane are 1000 and 500, respectively.

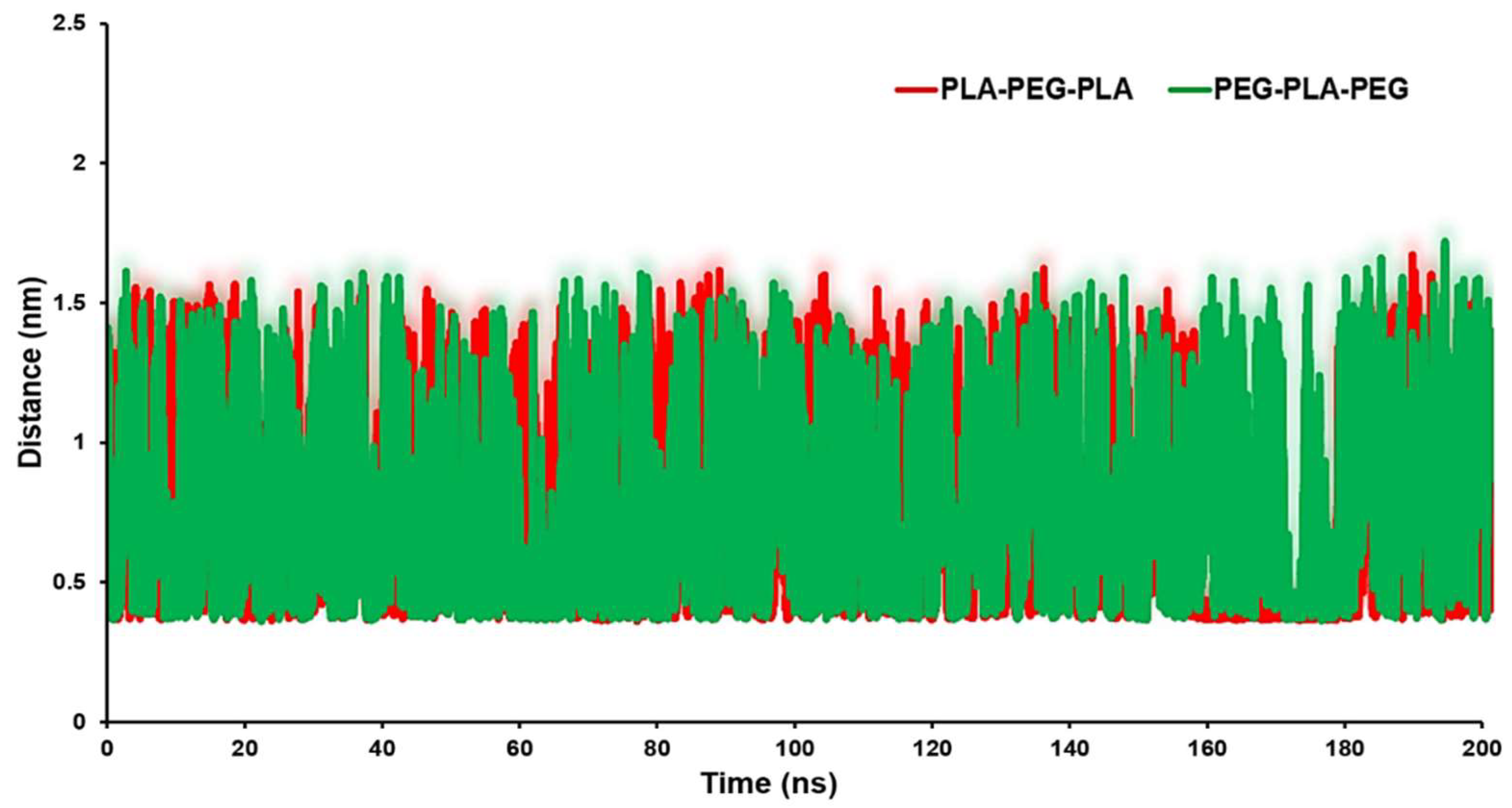

The distance analysis between the block copolymers and the biomembrane surface can be considered as an appropriate parameter to identify the interaction between the copolymers and the POPC surface.

Figure 7 exhibits the minimum distance of the center of mass (COM) of the block copolymers and membrane surface. The averages of distances were 0.85 nm for the POPC/PLA-PEG-PLA system and 0.94 nm for the POPC/ PEG-PLA-PEG.

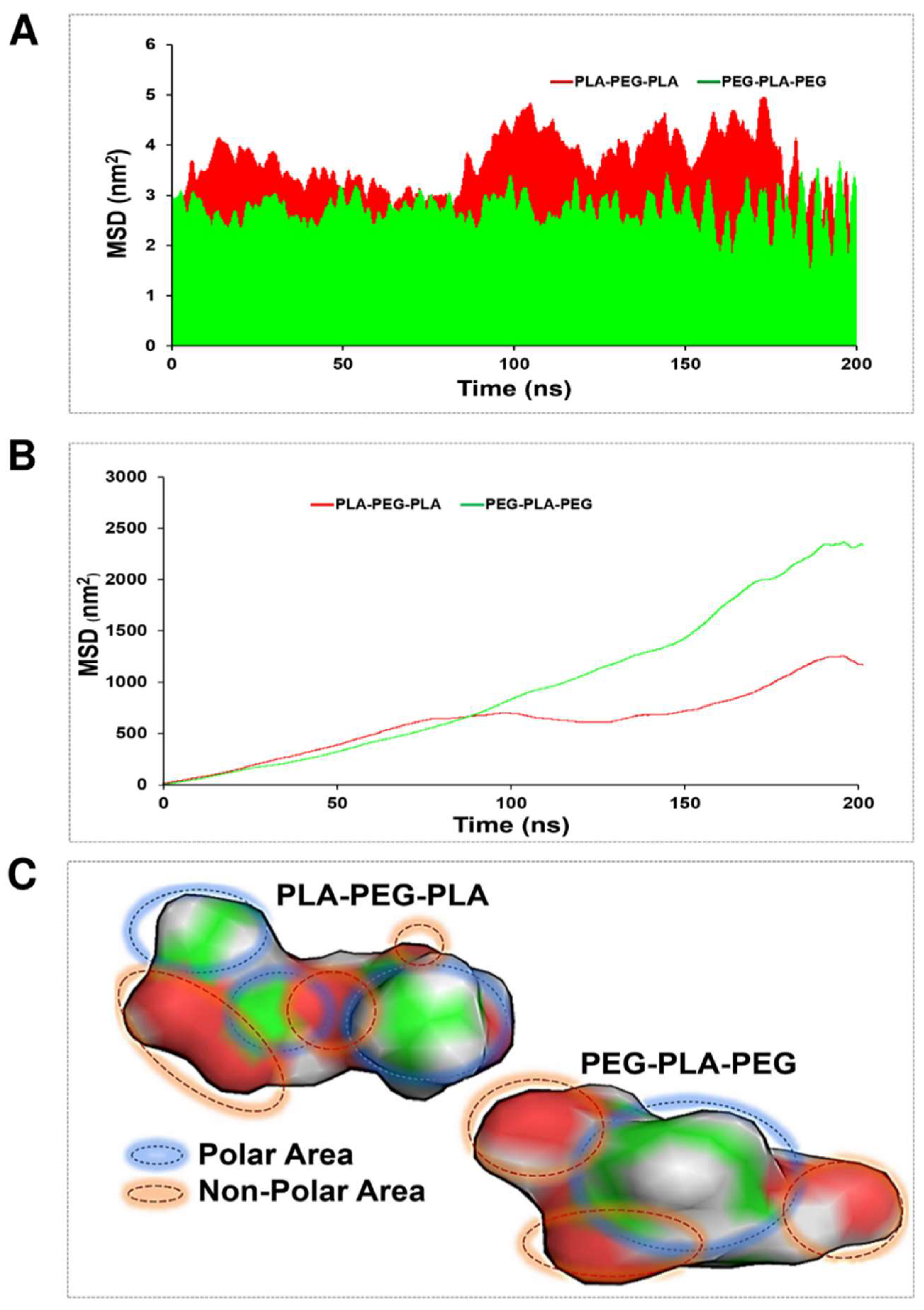

3.3. Membrane penetration

MSD function was calculated to evaluate the penetration ability of the studied copolymers in the POPC membrane. In this case, two strategies were considered to demonstrate copolymer diffusion: transverse and lateral diffusion. The average of transverse diffusion (

Figure 8A) for the PLA–PEG-PLA (3.67895 nm

2) and PEG–PLA-PEG (2.4654 nm

2) showed that the membrane penetration of PLA-PEG-PLA is much higher. But the average of lateral diffusion for the PLA–PEG-PLA (14.15 nm

2) and PEG–PLA-PEG (23.67 nm

2) showed that the membrane penetration of PEG-PLA-PEG is much higher. As shown in

Figure 8B, The PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG graph explains that at about 100 ns, both copolymers had almost the same speed of penetration into the membrane and had the same lateral penetration. After 100 ns, the function of the copolymers for lateral diffusion is different, and the lateral diffusion of the PEG-PLA-PEG molecule increases with a very speed slope in the polar area of the membrane, and PLA-PEG-PLA continues to propagate laterally with a much lower slope. At 180 ns, both copolymers are entrapped in the membrane and have fluctuation. Eventually, they resume their lateral diffusion after a few nanoseconds. From the obtained results, the higher mobility of the PEG-PLA-PEG molecule is clear in lateral diffusion. This finding is justified by following the molecule’s mobility around the head of the POPC membrane, and it should be noted that the non-polar area of the PEG-PLA-PEG molecule is smaller and the polar area is more uniform than the PLA-PEG-PLA molecule (

Figure 8C).

3.4. Energy calculations

Binding free energy is one of the most important and effective parameters for analyzing how the components interacted with each other inside the simulated box. Free energy by using MM/PBSA method was measured for extracted snapshots at every 250 ps of intervals from MD trajectories.

Table 3 represents the results of MM/PBSA calculations.

The binding free energy from Equation (2) is -3003.701 and -2797.846 for PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG, respectively. Moreover, the average amount of potential energy for the system containing PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG is -287450 and -256855 , respectively, which indicated that the system containing PLA-PEG-PLA has greater stability.

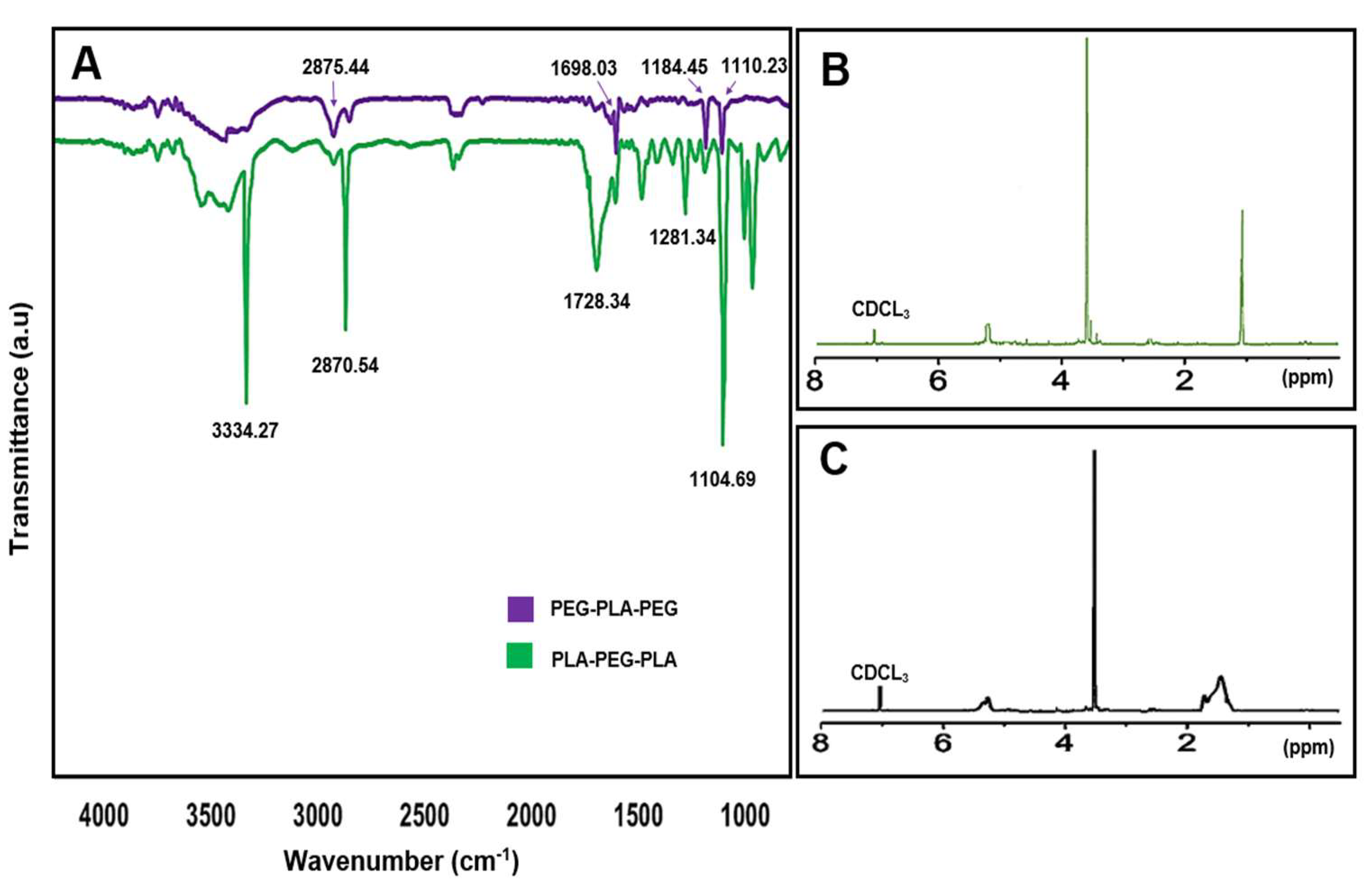

3.5. Characterization of synthesized copolymers

The chemical structure and composition of the synthesized block copolymers were determined by

1H-NMR and FT-IR. In the FT-IR analysis, the peaks corresponding to 1698.03 and 1728.34 cm

-1 indicate the carboxylic acid group in lactic acid, which is more strongly expressed in PLA-PEG-PLA (1728.34 cm

-1), and also the peak at 2875.44 and 2870.54 cm

-1 corresponded to (C-H) in the formation of the copolymer (

Figure 9A). Further,

1H-NMR spectra of the samples dissolved in Tetramethylsilane (CDCL

3) were used for confirmation of block copolymers formation, (

Figure 9B,C). For the PLA-PEG-PLA copolymer,

1H-NMR spectra of the block copolymer displayed peaks in 1.56 ppm and 5.17 ppm, which are repetitive units attributed to the methyl (CH

3) and methine (CH) groups of lactic acid, respectively. The peaks at 3.64 ppm and 3.48 ppm also refer to protons of the methylene group (CH

2) and methoxy end groups (CH

3O) in the PEG blocks, respectively. As a result, the peaks at 4.3 ppm correspond to methylene protons attached to methine groups in lactide monomers at the end of PEG chains. In the

1H-NMR spectra of PEG-PLA-PEG, the peaks at 5.17 ppm belong to (CH) of PLA, and 3.64 ppm are assigned to (CH

2) of PEG.

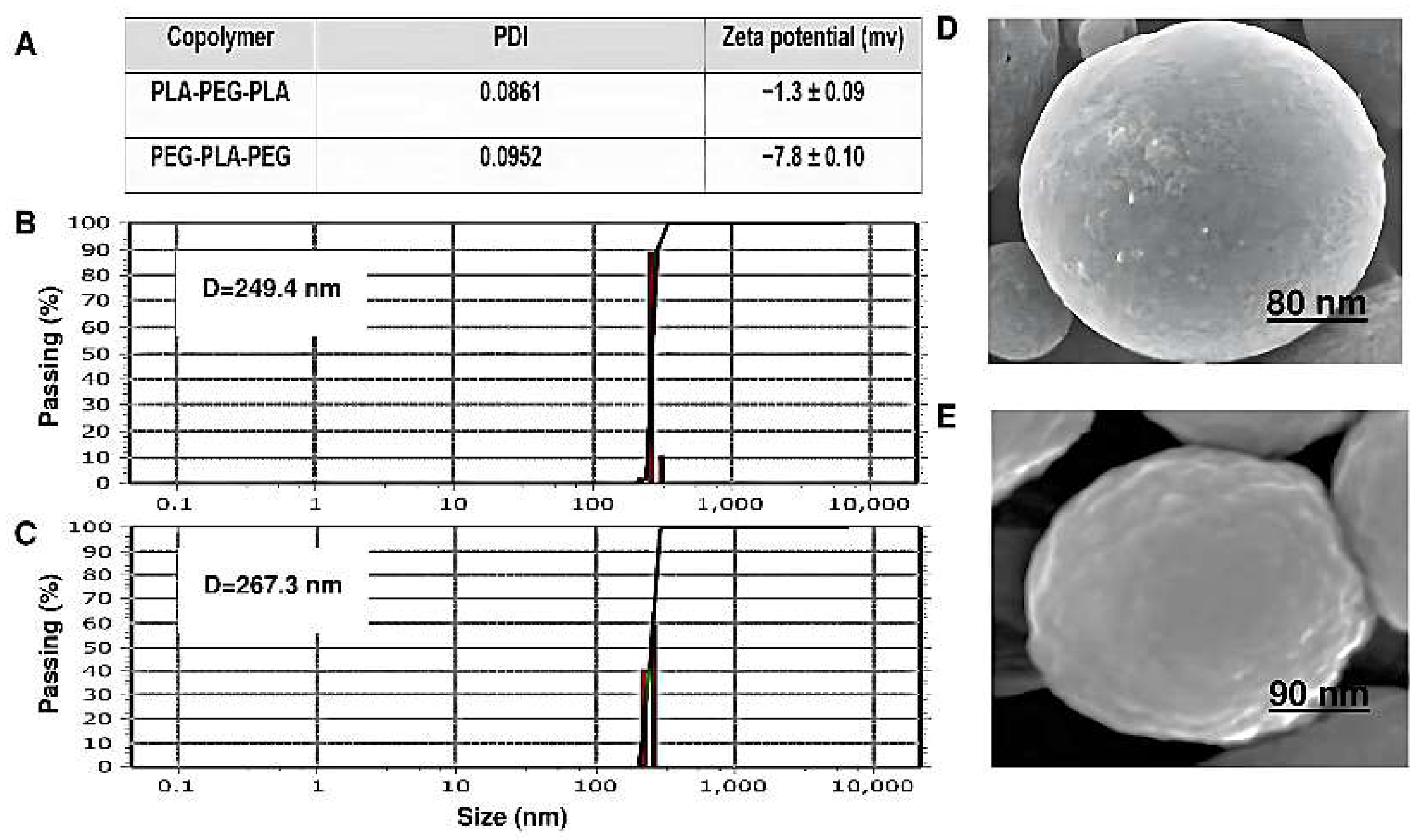

Particle size, surface morphology, and Zeta potential are shown in

Figure 10. The copolymer sizes were determined by DLS. The copolymers had a uniform particle size distribution. The diameter and Zeta potential of PEG-PLA-PEG were 249.4 nm and -7.8±0.1 mV, respectively. Also, the particle size for PLA-PEG-PLA increased to 267.3 nm compared to PEG-PLA-PEG. The Zeta potential of this sample was -1.3±0.09 mV. However, the size of the PEG-PLA-PEG observed by DLS was smaller than PLA-PEG-PLA and the charge of this copolymer is more negative. Additionally, the conjugation of polymers also influences their shape.

As shown in (

Figure 10D,E), the morphology of both the block copolymers has a regular spherical structure and a homogeneous surface without signs of collapse. However, the surface of PEG-PLA-PEG is slightly more swollen than PLA-PEG-PLA, which can appear during the drying step, and at the same magnification, it has a smaller diameter.

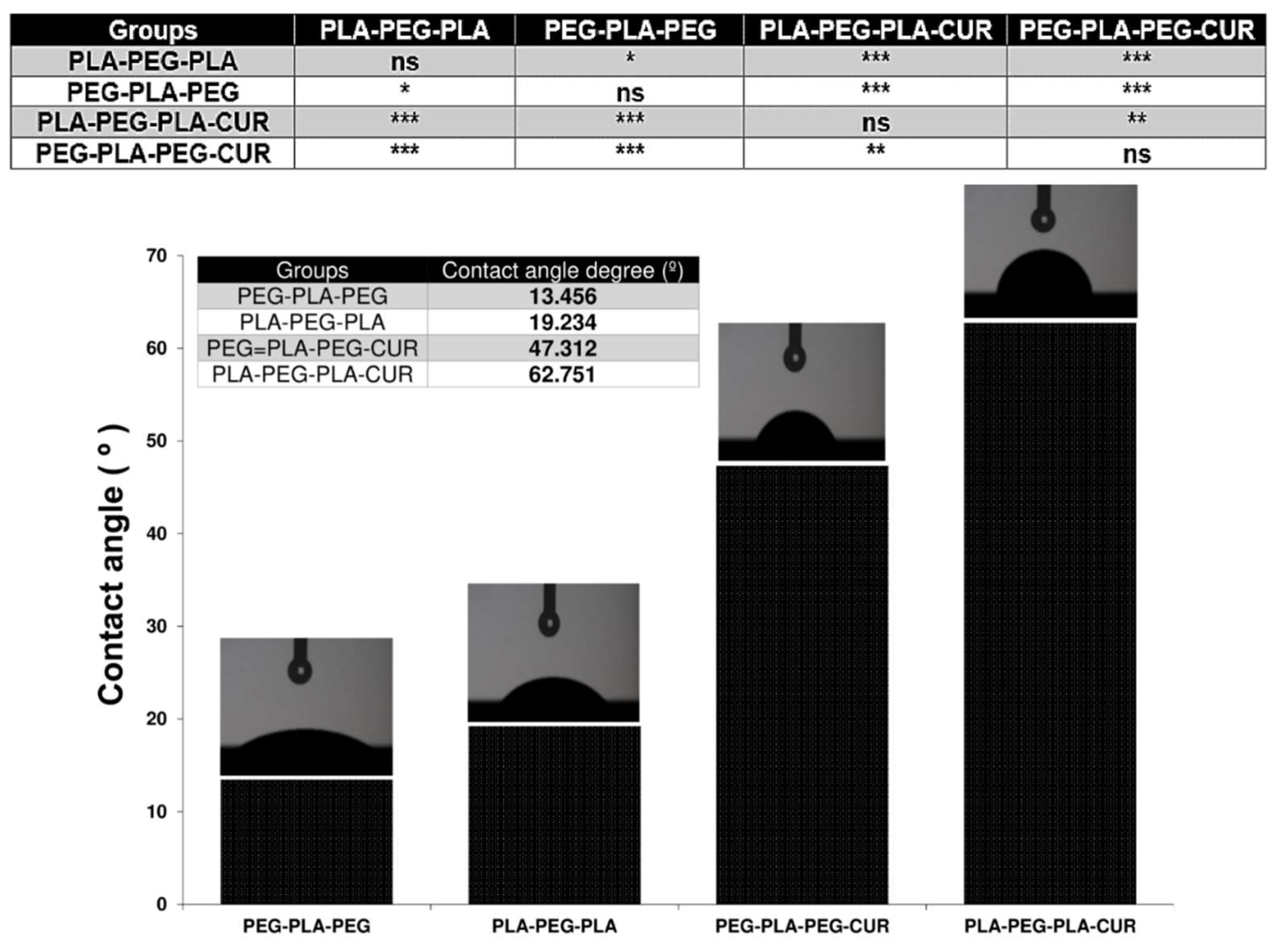

Another important feature of the copolymer surface is the degree of hydrophilicity that is displayed by contact angle measurement. The results of this analysis are shown in

Figure 11, and were 19.234 and 13.456º for PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG, respectively. Since their chain terminals are different, they have distinct degrees of hydrophilicity. When curcumin was added to the systems, the extent of hydrophilicity decreased and was reported as 62.751 for curcumin-PLA-PEG-PLA and 47.312 for curcumin-PEG-PLA-PEG.

3.6. Encapsulation efficiency and drug loading

Drug loading (DL) and encapsulation efficiency (EE) are strongly related to the w/w ratio of copolymers and curcumin. According to this study, the encapsulation efficiency in PLA-PEG-PLA for 1:50 w/w ratio was 43.9 ± 2.1%. However, in the 1:10 w/w ratio, the drug encapsulation efficiency was enhanced to 61.4 ± 1.4%. While at 1:50 w/w ratio the encapsulation efficiency in PEG-PLA-PEG, encapsulation efficiency was 36.2 ± 1.9, and at 1:10 increased to 52.3 ± 1.3% (

Table 4).

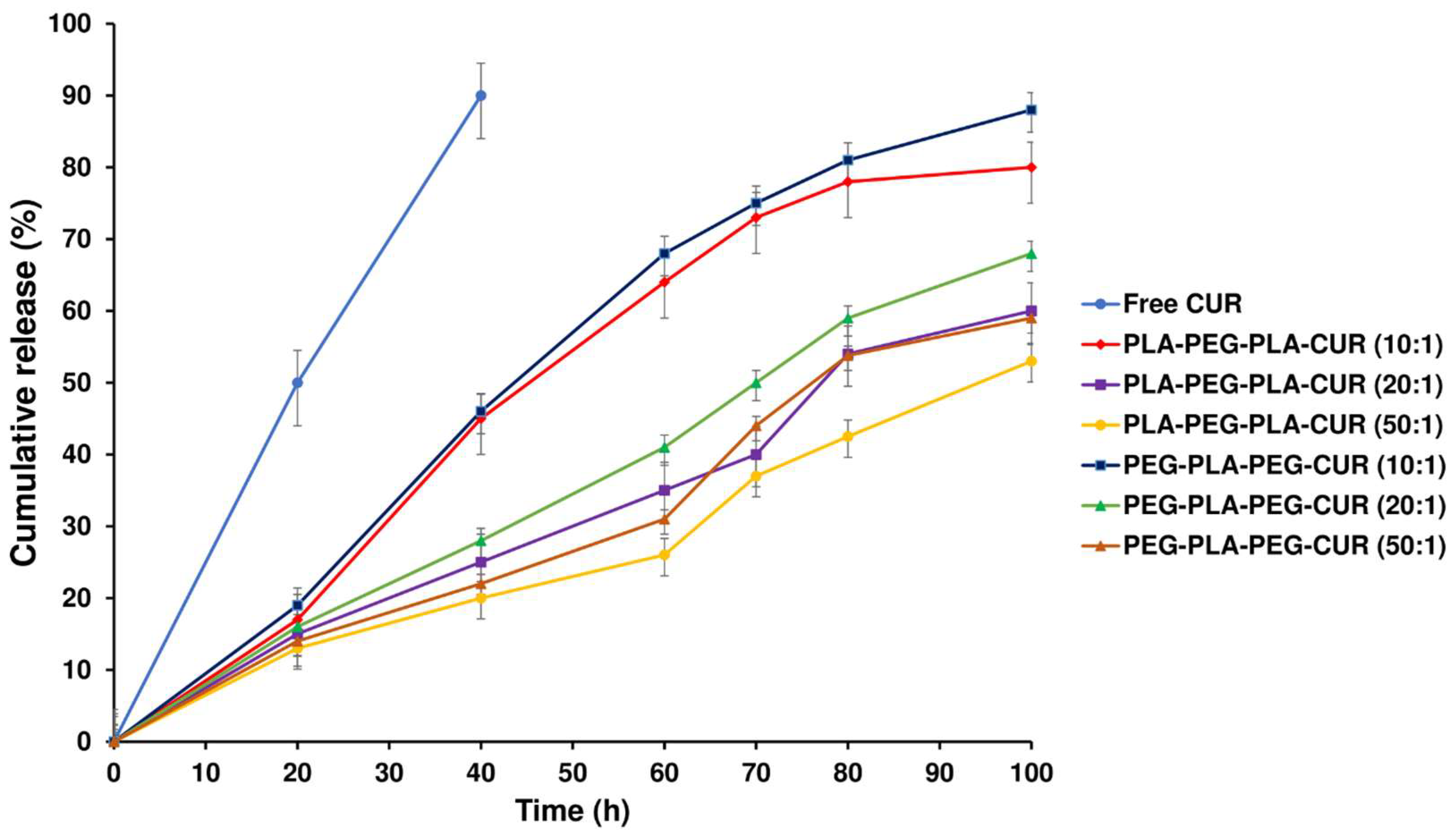

3.7. In vitro drug release study

The release profiles of curcumin from curcumin-loaded copolymers were evaluated to assess their potential as carriers for the drug. The curcumin release profiles for curcumin-loaded PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG with different w/w ratios are displayed in

Figure 12. A sustained release of curcumin was observed for 100 h by diffusing through the PLA-PEG-PLA copolymer compared with the free curcumin, which released 92% within 40 h. Initially, about 20% of the loaded drug rapidly was released in 18 h for two systems (curcumin-loaded PLA-PEG-PLA and curcumin-loaded PEG-PLA-PEG), then the drug was released slowly for the remaining time. Approximately 80% of the total curcumin loaded in PLA–PEG–PLA at 1:10 w/w ratio was gradually released over 100 h. The PLA–PEG–PLA released 60.3% and 53.8% of the total curcumin, respectively, at w/w ratios of 1:20 and 1:50. The release profile of PEG-PLA-PEG shows the same mechanism as the PLA-PEG-PLA. After 18 h about 20% of the loaded drug was released, then curcumin was released slowly up to 100 h. Approximately 88% of the curcumin loaded in PEG-PLA-PEG at 1:10 w/w ratio has been released over 100 h, which had a faster release than PLA-PEG-PLA. Also, at w/w ratios of 1:20 and 1:50, the total curcumin released 68.2% and 59%, respectively (

Figure 12).

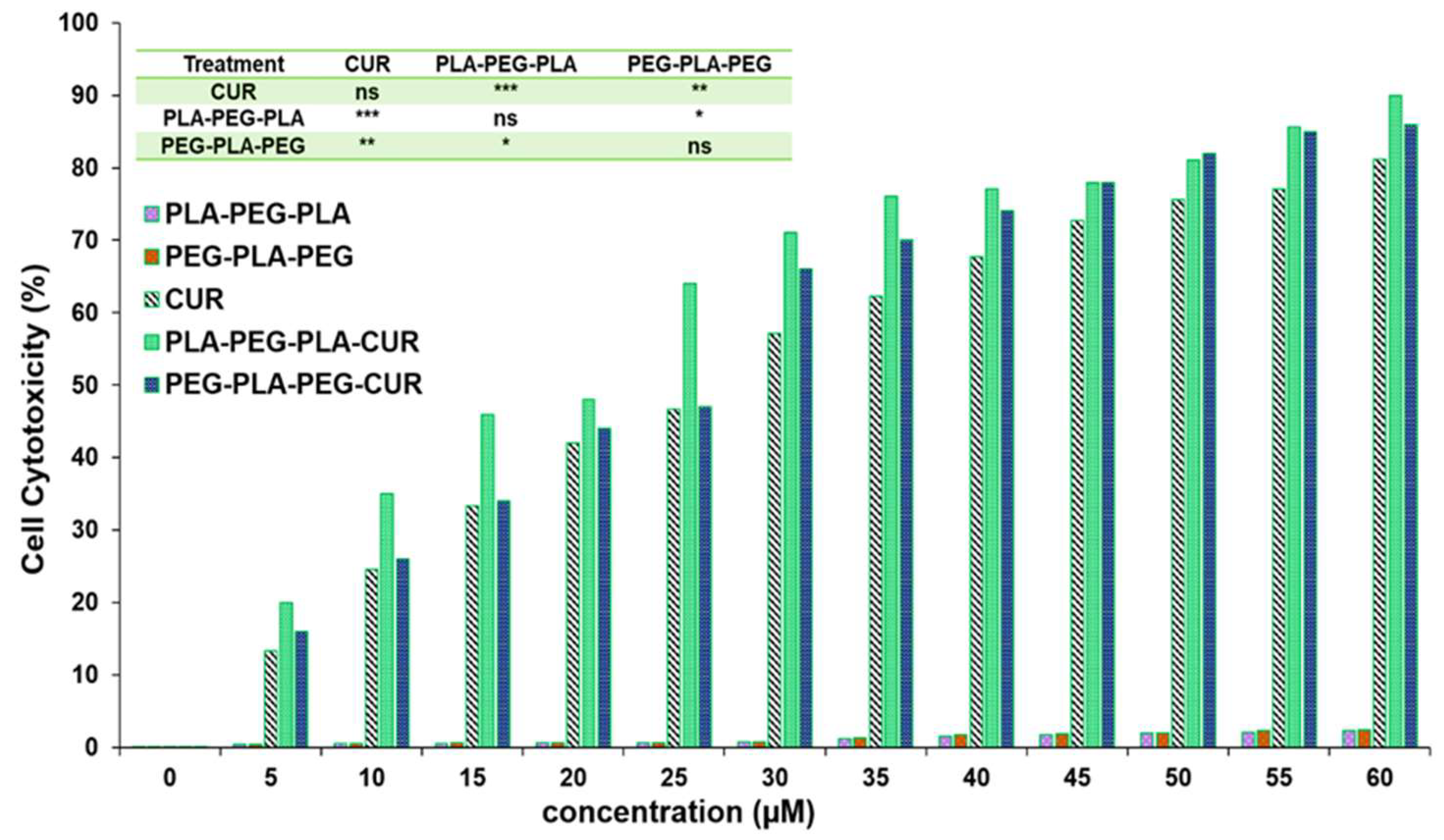

3.8. Cell viability studies

The effect of curcumin-loaded block copolymers on MCF-7 cell viability was studied using an MTT assay. Cell death increased with increasing concentration of curcumin (

Figure 13). The results indicated that PLA-PEG-PLA-curcumin reduced the cancer cell viability to a greater extent compared to PEG-PLA-PEG- curcumin and free curcumin. The IC

50 value of curcumin was 29.8 µM ± 0.61, while this concentration (29.8 µM) of curcumin delivered through curcumin-PLA-PEG-PLA and curcumin-PEG-PLA-PEG increased the cell death to 62.3% ± 0.79 and 57.6% ± 0.53, respectively. The IC

50 values for curcumin-PLA-PEG-PLA and curcumin-PEG-PLA-PEG were calculated to be 23.01 ± 0.85 and 26.87 ± 0.49 µM, respectively. The cell death at 60 µM curcumin equivalent after 48 hours were reported to be 80.4 ± 0.99 for curcumin, 85.3 ± 0.76 for curcumin-PEG-PLA-PEG, and 91.1 ± 1.01 for curcumin-PLA-PEG-PLA. These results suggested that curcumin-PLA-PEG-PLA, is the most effective system for inducing cancer cell death.

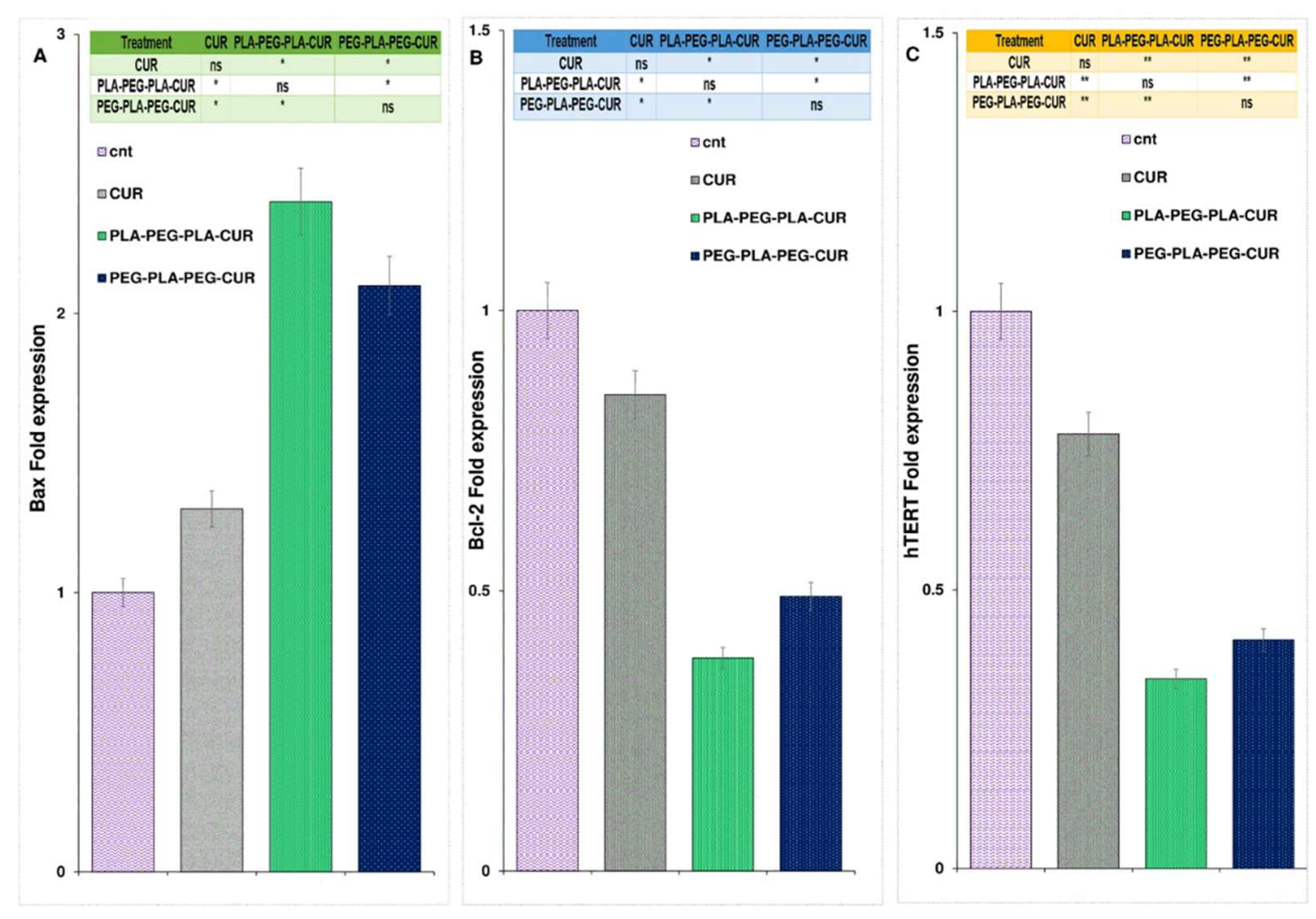

3.9. Gene expression analysis

The expression of the Bax gene increased and was found to be 2.4 fold higher for curcumin-PLA-PEG-PLA, 2.1 fold higher for curcumin-PEG-PLA-PEG, and 1.3 fold higher for curcumin-treated cells compared to control cells (

Figure 14A). As shown in

Figure 14B, gene expression analysis showed a significant reduction in Bcl-2 levels in curcumin-copolymers and curcumin-treated cells after 48 h of treatment. The Bcl-2 fold change for curcumin, curcumin-PLA-PEG-PLA, and curcumin-PEG-PLA-PEG were 0.85, 0.38, and 0.49, respectively. Also, the expression level of the hTERT gene was reduced in curcumin, curcumin-PLA-PEG-PLA, and curcumin-PEG-PLA-PEG-treated cells and the fold change in expression were 0.78, 0.34, and 0.41-fold compared to PBS-treated cells, respectively (

Figure 14).

4. Discussion

The study of nanocarrier behavior is essential to ensure steady and controlled drug release at the target site. Hence, the determination of structural properties, surface characterization, and permeation tendency into the biomembrane is critical for designing carriers such as copolymers for the delivery of drugs [

41,

42]. The extent of hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity is an important characteristic of the copolymers, which can be approximately accessed via contact angle [

43,

44]. For the analysis of water penetration into the POPC membrane by MD simulation, RDF was enforced so that the highest peak corresponds to the maximum value of the density variation from the reference of water molecules at that distance [

45]. The peak for copolymers was close and very sharp at 0.385nm, and the penetration of water molecules into the POPC was high. However, there was a quantitative difference in the average RDF for both copolymers, so the amount of accumulation of water molecules around the membrane was higher in the presence of PEG-PLA-PEG.

These results may point to the greater polarity of PEG-PLA-PEG compared to PLA-PEG-PLA copolymer, as shown by the homogeneous red areas of the PEG-PLA-PEG in

Figure 8C. Therefore, we expected a more negative value of Zeta potential for PEG-PLA-PEG, which was then confirmed in

Figure 10A, indicated that the surface charge of the PEG-PLA-PEG was more negative compared to PLA-PEG-PLA. However, RDF and Zeta results gave limited information about the hydrophilic properties of copolymers. Thus, the contact angle was compared for each system. It was unexpected that the simulation predictions followed the experimental data. PEG-PLA-PEG had a smaller contact angle, and it can be argued this copolymer is more hydrophilic than PLA-PEG-PLA.

MSD analysis was used to obtain more accurate results from the copolymer’s penetration into the membrane. In this case, two theories have been considered to demonstrate copolymer penetration: transverse and lateral diffusion. Each theory shows a different function of copolymers.

Figure 8 illustrates the differences between the two. Lateral diffusion is greater for PEG-PLA-PEG than the PLA-PEG-PLA molecule, suggesting that the PEG-PLA-PEG molecule is more active across the hydrophilic area of the membrane, and PLA-PEG-PLA has better penetration along the Z-axis.

At transverse diffusion, the highest peaks occur at times 48, 101, 150, and 190 ns, which is longer for PLA-PED-PLA than PEG-PLA-PEG. The greater transverse diffusion of molecule PLA-PEG-PLA and its ups and downs along the Z-axis can depend on two factors that are explained in

Figure 8C. This behavior can be described based on the length of the carbon chain in the copolymers. The PLA-PEG-PLA molecule (C

8H

14O

6) has a longer chain of carbon, while the PEG-PLA-PEG molecule (C

7H

14O

5) has a shorter chain. Hence, the non-polar chain causes more interaction with the hydrophobic area of the POPC membrane and penetrates more easily. The second reason for the greater PLA-PEG-PLA transverse penetration is related to the polar region of the molecules. As shown in

Figure 8, the polar regions of the PEG-PLA-PEG molecule exhibit a more homogeneous distribution. This can be considered the key to the dynamism of the PEG-PLA-PEG molecule in the polar area of the membrane laterally and in trying to move and stay in the width of the membrane.

Further, contact number and distance illustrated the interaction between the tail of the copolymers chain and the membrane surface. The oxygen atom in the PLA-PEG-PLA chain tail has more electronegativity than the carbon atom in the PEG-PLA-PEG chain tail. A high affinity to interact with the hydrogen atoms on the POPC and more contact with the membrane surface can be correlated with better penetration of PLA-PEG-PLA. Also, the long-distance indicates weak interaction and lower binding affinity between copolymers and the membrane. The systems containing PLA-PEG-PLA have a small distance with membrane throughout the MD simulation. As a result of cell penetration and the tendency of PLA-PEG-PLA to connect more strongly to the cell membrane, this copolymer should be more effective as a delivery agent and also the release of curcumin is slower from this copolymer owing to its higher hydrophobic content, also demonstrated by curcumin release studies. Due to the higher hydrophobicity of PLA-PEG-PLA over PEG-PLA-PEG, this copolymer offered more chances for drug release from its hydrophobic core. Moreover, the drug release profile explained that the burst release of the PLA-PEG-PLA copolymer was less than the other two systems, and a slower drug release was observed in this copolymer. Different hydrolysis-induced degradation rates of polymers may explain such differences in drug release profiles. Hence, a higher ratio of hydrophilic PEG to hydrophobic PLA caused polymer destruction and higher drug release at initial time points in PEG-PLA-PEG systems, and the curcumin-release profile from PLA-PEG-PLA was more controlled.

Moreover, free energy binding results express some facts about nanocarriers. Free energy binding values, which indicate better PLA-PEG-PLA performance, show a tendency for this copolymer to be more dynamic on the Z-axis of the membrane. Hence, the results of type diffusion and lateral diffusion can be explained. Considering that curcumin is a hydrophobic drug and to facilitate its release [

46], a hydrophilic carrier with a hydrophobic core such as PLA-PEG-PLA can improve the effectiveness of this compound.

Favorable attributes of PLA-PEG-PLA, including higher drug loading and slow release of loaded curcumin, are likely the key contributors to increased cell death in MCF-7 cells. Further, this copolymer affected the gene expression levels to the greatest extent compared to curcumin and curcumin-PEG-PLA-PEG. The decrease in Bcl-2 and hTERT expression and increase in Bax expression correlates with apoptosis-mediated death of MCF-7 cells [

47,

48,

49]. Overall, our results indicated that PLA-PEG-PLA is an efficient delivery vehicle for hydrophobic drugs such as curcumin.

5. Conclusions

The main purpose of this study was to determine the potency of linear triblock copolymers (PLA–PEG–PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG) to interact with the cell membrane and their consequent ability to deliver curcumin based on MD simulations and in vitro investigation. MD results showed that PLA-PEG-PLA copolymer has greater interaction potency with POPC membrane compared to PEG-PLA-PEG. According to energy analysis, PLA-PEG-PLA is more stable than PEG-PLA-PEG. Hence, PLA-PEG-PLA with its greater stability in aqueous systems and greater penetration into the cell membrane is likely to be a good candidate for intracellular delivery of hydrophobic drugs. Experimental analysis results including 1H-NMR and FT-IR confirmed the copolymers’ synthesis. The size, charge, and morphology of the copolymers were in agreement with the simulation results. Furthermore, PLA-PEG-PLA, with its higher drug loading and controlled release rates, induced greater death in the MCF-7 cells and affected the gene expression to a greater extent, suggesting this copolymer as a potential candidate for delivery of curcumin and other hydrophobic drugs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.R., M.M.G., V.N.U., B.R.S., and R.H.; methodology, N.R., H.N., and A.T.; software, N.R., M.M.G., and H.N.; validation, M.A.; formal analysis, A.G. and M.S.; investigation, N.R., M.S., and M.M.G.; resources, A.T.; data curation, F.F.; writing—original draft preparation, F.F. and A.A.Y.; writing—review and editing, N.R., M.K., M.K., and V.N.U.; visualization, A.G.; supervision, V.N.U., B.R.S., and R.H.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses gratitude to the Amirkabir University of Technology for their scientific and technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Behl, A.; Chhillar, A.K. Nano-Based Drug Delivery of Anticancer Chemotherapeutic Drugs Targeting Breast Cancer. Recent patents on anti-cancer drug discovery 2023, 18, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narvekar, M.; Xue, H.Y.; Eoh, J.Y.; Wong, H.L. Nanocarrier for poorly water-soluble anticancer drugs--barriers of translation and solutions. AAPS PharmSciTech 2014, 15, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veselov, V.V.; Nosyrev, A.E.; Jicsinszky, L.; Alyautdin, R.N.; Cravotto, G. Targeted Delivery Methods for Anticancer Drugs. Cancers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Ghosh, B.; Biswas, S. Nanocarriers for cancer-targeted drug delivery. Journal of drug targeting 2016, 24, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.H.; Mir, M.; Qian, L.; Baloch, M.; Ali Khan, M.F.; Rehman, A.U.; Ngowi, E.E.; Wu, D.D.; Ji, X.Y. Skin cancer biology and barriers to treatment: Recent applications of polymeric micro/nanostructures. Journal of advanced research 2022, 36, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuperkar, K.; Patel, D.; Atanase, L.I.; Bahadur, P. Amphiphilic Block Copolymers: Their Structures, and Self-Assembly to Polymeric Micelles and Polymersomes as Drug Delivery Vehicles. Polymers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Yang, B.; Jiang, T.; Li, Y.M.; He, F.; Zhuo, R.X. Folate-conjugated amphiphilic block copolymers for targeted and efficient delivery of doxorubicin. Colloids and surfaces. B, Biointerfaces 2014, 115, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Sosnik, A.; Concheiro, A. PEO-PPO block copolymers for passive micellar targeting and overcoming multidrug resistance in cancer therapy. Current drug targets 2011, 12, 1112–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Shao, D.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, B.B.; Kong, J. pH-responsive dithiomaleimide-amphiphilic block copolymer for drug delivery and cellular imaging. Journal of colloid and interface science 2019, 552, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahkulubey Kahveci, E.L.; Kahveci, M.U.; Celebi, A.; Avsar, T.; Derman, S. Glycopolymer and Poly(β-amino ester)-Based Amphiphilic Block Copolymer as a Drug Carrier. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 4896–4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yang, P.; Ma, H.; Yin, W.; Wu, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, D.; Zhang, X. Amphiphilic block copolymers-based mixed micelles for noninvasive drug delivery. Drug delivery 2016, 23, 3063–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Lin, F.; You, D.; Qian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bi, Y. Self-Assembly and Enzyme Responsiveness of Amphiphilic Linear-Dendritic Block Copolymers Based on Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) and Dendritic Phenylalanyl-lysine Dipeptides. Polymers 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, X.; Hao, L.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Q.; Sheng, R. Charge-Convertible and Reduction-Sensitive Cholesterol-Containing Amphiphilic Copolymers for Improved Doxorubicin Delivery. Materials (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.; Xia, C.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Li, D. Self-assembled amphiphilic copolymers-doxorubicin conjugated nanoparticles for gastric cancer therapy with low in vivo toxicity and high efficacy. Journal of biomaterials science. Polymer edition 2022, 33, 2202–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Olofsson, K.; Fan, Y.; Sánchez, C.C.; Andrén, O.C.J.; Qin, L.; Fortuin, L.; Jonsson, E.M.; Malkoch, M. Novel Therapeutic Platform of Micelles and Nanogels from Dopa-Functionalized Triblock Copolymers. Small (Weinheim an der Bergstrasse, Germany) 2021, 17, e2007305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Chen, M.; Luo, T.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Sapin-Minet, A.; Gaucher, C.; Xia, X. ROS and GSH-responsive S-nitrosoglutathione functionalized polymeric nanoparticles to overcome multidrug resistance in cancer. Acta biomaterialia 2020, 103, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, J.W.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Luo, C.; Han, H.; Xu, Z.K.; Yao, K. A novel gatifloxacin-loaded intraocular lens for prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis. Bioactive materials 2023, 20, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Bae, A.J.; Su, Y.J.; Pozveh, S.G.; Bodenschatz, E.; Pumir, A.; Gholami, A. Bio-hybrid micro-swimmers propelled by flagella isolated from C. reinhardtii. Soft matter 2022, 18, 4767–4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, A.; Kabiri, T.; Shafiee, S.; Hamidi, A. Preparation and Characterization of PLA-PEG-PLA/PEI/DNA Nanoparticles for Improvement of Transfection Efficiency and Controlled Release of DNA in Gene Delivery Systems. Iranian journal of pharmaceutical research : IJPR 2019, 18, 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, R.; Abdollahi, M.; Emamgholi Zadeh, E.; Khodabakhshi, K.; Badeli, A.; Bagheri, H.; Hosseinkhani, S. mPEG-PLA and PLA-PEG-PLA nanoparticles as new carriers for delivery of recombinant human Growth Hormone (rhGH). Scientific reports 2018, 8, 9854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, H.L.; Pan, L.H.; Li, Q.M.; Luo, J.P.; Zha, X.Q. The nanomicelles consisting of lotus root amylopectin and quinoa protein: Construction and encapsulation for quercetin. Food chemistry 2022, 387, 132924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, M.G.C.; Pound-Lana, G.; de Oliveira, M.A.; Lanna, E.G.; Fialho, M.C.P.; de Brito, A.C.F.; Barboza, A.P.M.; Aguiar-Soares, R.D.O.; Mosqueira, V.C.F. Labeling PLA-PEG nanocarriers with IR780: physical entrapment versus covalent attachment to polylactide. Drug delivery and translational research 2020, 10, 1626–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, N.; Davarnejad, R. Characterization of folic acid-functionalized PLA-PEG nanomicelle to deliver Letrozole: A nanoinformatics study. IET nanobiotechnology 2022, 16, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: validation based on comparison to NMR data. Journal of computational chemistry 2013, 34, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Klauda, J.B. Update of the CHARMM36 United Atom Chain Model for Hydrocarbons and Phospholipids. The journal of physical chemistry. B 2020, 124, 6797–6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Cheng, X.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Park, S.J.; Patel, D.S.; Beaven, A.H.; Lee, K.I.; Rui, H.; Park, S. , et al. CHARMM-GUI 10 years for biomolecular modeling and simulation. Journal of computational chemistry 2017, 38, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, S.A.; Bostick, D.; Berkowitz, M.L. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of a Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine Bilayer with NaCl. Biophysical Journal 2003, 84, 3743–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, N.; Davarnejad, R. Characterization of folic acid-functionalized PLA–PEG nanomicelle to deliver Letrozole: A nanoinformatics study. IET nanobiotechnology 2022, 16, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A.E.; Berendsen, H.J. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. Journal of computational chemistry 2005, 26, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzner, C.; Páll, S.; Fechner, M.; Esztermann, A.; de Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H. More bang for your buck: Improved use of GPU nodes for GROMACS 2018. Journal of computational chemistry 2019, 40, 2418–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwasra, R.; Fatihi, S.; Raza, K.; Singh, S.; Khanna, K.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, N.; Varma, S. Filgrastim loading in PLGA and SLN nanoparticulate system: a bioinformatics approach. Drug development and industrial pharmacy 2020, 46, 1354–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Badhe, Y.; Mitragotri, S.; Rai, B. Permeation of nanoparticles across the intestinal lipid membrane: dependence on shape and surface chemistry studied through molecular simulations. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 6318–6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, M.A.F.; Habitzreuter, M.A.; Schwade, M.H.; Borrasca, R.; Antonacci, M.; Gonzatti, G.K.; Netz, P.A.; Barbosa, M.C. Dynamical aspects of supercooled TIP3P-water in the grooves of DNA. The Journal of chemical physics 2019, 150, 235101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomari, M.M.; Tarighi, P.; Choupani, E.; Abkhiz, S.; Mohamadzadeh, M.; Rostami, N.; Sadroddiny, E.; Baammi, S.; Uversky, V.N.; Dokholyan, N.V. Structural evolution of Delta lineage of SARS-CoV-2. International journal of biological macromolecules 2023, 226, 1116–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefpour, A.; Modarress, H.; Goharpey, F.; Amjad-Iranagh, S. Interaction of PEGylated anti-hypertensive drugs, amlodipine, atenolol and lisinopril with lipid bilayer membrane: A molecular dynamics simulation study. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2015, 1848, 1687–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, C.; Watanabe, H.; Fukuzawa, K.; Parker, L.J.; Okiyama, Y.; Yuki, H.; Yokoyama, S.; Nakano, H.; Tanaka, S.; Honma, T. Theoretical Analysis of Activity Cliffs among Benzofuranone-Class Pim1 Inhibitors Using the Fragment Molecular Orbital Method with Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (FMO+MM-PBSA) Approach. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2017, 57, 2996–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Kumar, R.; Lynn, A. g_mmpbsa--a GROMACS tool for high-throughput MM-PBSA calculations. J Chem Inf Model 2014, 54, 1951–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricheldorf, H.R.; Weidner, S.M. The Ring-Opening Polymerization-Polycondensation (ROPPOC) Approach to Cyclic Polymers. Macromolecular rapid communications 2020, 41, e2000152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttreddy, R.; Rautiainen, J.M.; Mäkelä, T.; Rissanen, K. Strong N-X⋅⋅⋅O-N Halogen Bonds: A Comprehensive Study on N-Halosaccharin Pyridine N-Oxide Complexes. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2019, 58, 18610–18618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutalik, S.; Suthar, N.A.; Managuli, R.S.; Shetty, P.K.; Avadhani, K.; Kalthur, G.; Kulkarni, R.V.; Thomas, R. Development and performance evaluation of novel nanoparticles of a grafted copolymer loaded with curcumin. International journal of biological macromolecules 2016, 86, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Marioli, M.; Zhang, K. Analytical characterization of liposomes and other lipid nanoparticles for drug delivery. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis 2021, 192, 113642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joudeh, N.; Linke, D. Nanoparticle classification, physicochemical properties, characterization, and applications: a comprehensive review for biologists. Journal of nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig-Rigall, J.; Fernández-Rubio, C.; González-Benito, J.; Houston, J.E.; Radulescu, A.; Nguewa, P.; González-Gaitano, G. Structural characterization by scattering and spectroscopic methods and biological evaluation of polymeric micelles of poloxamines and TPGS as nanocarriers for miltefosine delivery. International journal of pharmaceutics 2020, 578, 119057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad Fauzi, A.A.; Osman, A.F.; Alosime, E.M.; Ibrahim, I.; Abdul Halim, K.A.; Ismail, H. Strategies towards Producing Non-Polar Dolomite Nanoparticles as Nanofiller for Copolymer Nanocomposite. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, U.; Kartha, T.R.; Madhurima, V. Radial distribution and hydrogen bonded network graphs of alcohol-aniline binary mixture. Journal of molecular modeling 2023, 29, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, H.; Shakeri, A.; Rashidi, B.; Jalili, A.; Banikazemi, Z.; Sahebkar, A. Phytosomal curcumin: A review of pharmacokinetic, experimental and clinical studies. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 2017, 85, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, J.M.; Soane, L. Multiple functions of BCL-2 family proteins. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, K.; Hertlein, V.; Jenner, A.; Dellmann, T.; Gojkovic, M.; Peña-Blanco, A.; Dadsena, S.; Wajngarten, N.; Danial, J.S.H.; Thevathasan, J.V. , et al. The interplay between BAX and BAK tunes apoptotic pore growth to control mitochondrial-DNA-mediated inflammation. Molecular cell 2022, 82, 933–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.; Latonen, L.; Wiman, K.G. hTERT antagonizes p53-induced apoptosis independently of telomerase activity. Oncogene 2005, 24, 1320–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the work cycle utilized in this study.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the work cycle utilized in this study.

Figure 2.

RMSD values of PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG.

Figure 2.

RMSD values of PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG.

Figure 3.

RMSF analysis for PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG.

Figure 3.

RMSF analysis for PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG.

Figure 4.

Comparative RDF to analyze the water penetration capability to pass through POPC in PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG systems (the graph of the designed systems aligned with each other).

Figure 4.

Comparative RDF to analyze the water penetration capability to pass through POPC in PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG systems (the graph of the designed systems aligned with each other).

Figure 5.

SASA analysis for PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG.

Figure 5.

SASA analysis for PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG.

Figure 6.

Contact number analysis for PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG to POPC membrane.

Figure 6.

Contact number analysis for PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG to POPC membrane.

Figure 7.

Distance between target copolymers and POPC membrane.

Figure 7.

Distance between target copolymers and POPC membrane.

Figure 8.

MSD evaluation for PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG. A) Transverse diffusion, B) lateral diffusion, C) Polar and non-Polar Areas of block copolymers via Gauss View.

Figure 8.

MSD evaluation for PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG. A) Transverse diffusion, B) lateral diffusion, C) Polar and non-Polar Areas of block copolymers via Gauss View.

Figure 9.

(A) The FT-IR spectra of copolymers, (B) 1H-NMR spectra of PLA–PEG–PLA, (C) 1H-NMR spectra of PEG-PLA-PEG.

Figure 9.

(A) The FT-IR spectra of copolymers, (B) 1H-NMR spectra of PLA–PEG–PLA, (C) 1H-NMR spectra of PEG-PLA-PEG.

Figure 10.

Characterization and morphology investigation. (A) Zeta potential and polydispersity index (PDI) measurements of copolymers, (B) Average particle size diameter of PEG-PLA-PEG, (C) Average particle size diameter of PLA-PEG-PLA, (D) SEM images of PLA-PEG-PLA, and (E) SEM images of PEG-PLA-PEG.

Figure 10.

Characterization and morphology investigation. (A) Zeta potential and polydispersity index (PDI) measurements of copolymers, (B) Average particle size diameter of PEG-PLA-PEG, (C) Average particle size diameter of PLA-PEG-PLA, (D) SEM images of PLA-PEG-PLA, and (E) SEM images of PEG-PLA-PEG.

Figure 11.

Contact angle measurements. Values represent the mean ± SD and data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA (n = 4). p*** < 0.001.

Figure 11.

Contact angle measurements. Values represent the mean ± SD and data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA (n = 4). p*** < 0.001.

Figure 12.

In vitro release of free curcumin and curcumin-loaded PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG at various w/w ratios.

Figure 12.

In vitro release of free curcumin and curcumin-loaded PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG at various w/w ratios.

Figure 13.

Evaluating the inhibitory effect of curcumin-Copolymers on MCF-7 cancer cells at 48 h. Values represent the mean ± SD and data were evaluated using one-way ANOVA (n = 3). p* < 0.05, p** < 0.01, p*** < 0.001.

Figure 13.

Evaluating the inhibitory effect of curcumin-Copolymers on MCF-7 cancer cells at 48 h. Values represent the mean ± SD and data were evaluated using one-way ANOVA (n = 3). p* < 0.05, p** < 0.01, p*** < 0.001.

Figure 14.

The figure illustrates the alterations in the expression of Bax (A), Bcl-2 (B), and hTERT genes following the administration of curcumin and the designed copolymers over a 48-hour period. Gene expression analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA with a sample size of three (n = 3). Statistical significance levels are denoted as p* < 0.05, p** < 0.01, and p*** < 0.001.

Figure 14.

The figure illustrates the alterations in the expression of Bax (A), Bcl-2 (B), and hTERT genes following the administration of curcumin and the designed copolymers over a 48-hour period. Gene expression analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA with a sample size of three (n = 3). Statistical significance levels are denoted as p* < 0.05, p** < 0.01, and p*** < 0.001.

Table 1.

Target molecules along with their chemical features.

Table 1.

Target molecules along with their chemical features.

| Name |

Molecular Formula |

3D structure |

PubChem ID |

| DL-Lactic acid |

CH3CHOHCOOH |

|

612 |

| Ethane-1,2-diol |

HOCH2CH2OH |

|

174 |

Table 2.

Designed primers information.

Table 2.

Designed primers information.

| Gene name |

Primer sequence |

Strand |

product size |

| BAX |

AAACTGGTGCTCAAGGCCC |

Plus |

81 |

| CCGGAGGAAGTCCAATGTCC |

Minus |

| BCL2 |

TGGGATCGTTGCCTTATGCA |

Plus |

101 |

| GTCTACTTCCTCTGTGATGTTGT |

Minus |

| hTERT |

AACCTTCCTCAGGACCCTGG |

Plus |

128 |

| CCGGCATCTGAACAAAAGCC |

Minus |

| GAPDH |

TGGAAGGACTCATGACCACA |

Plus |

119 |

| AGAGGCAGGGATGATGTTCT |

Minus |

Table 3.

Binding free energy terms information for studied systems.

Table 3.

Binding free energy terms information for studied systems.

| Copolymer |

Energy(kJ/mol) |

| Van der Waal energy |

Electrostatic energy |

Polar solvation energy |

SASA energy |

Entropy |

| PLA-PEG-PLA |

-11.203 |

-5.649 |

36.657 |

-1.936 |

9.747 |

| PEG-PLA-PEG |

-3.859 |

-2.884 |

27.055 |

-0.878 |

9.088 |

Table 4.

Drug loading (DL) and encapsulation efficiency (EE) of curcumin at various drug-polymer ratios.

Table 4.

Drug loading (DL) and encapsulation efficiency (EE) of curcumin at various drug-polymer ratios.

| Systems |

Ratio (w/w) CUR: Copolymers |

DL (%) |

EE (%) |

| Curcumin-PLA-PEG-PLA |

1:50 |

1.9± 0.3 |

43.9 ± 2.1 |

| 1:20 |

4.4 ± 0.1 |

51.7 ± 2.5 |

| 1:10 |

6.3 ± 0.2 |

61.4 ± 1.4 |

| Curcumin-PEG-PLA-PEG |

1:50 |

1.2 ± 0.1 |

36.2 ± 1.9 |

| 1:20 |

3.6 ± 0.3 |

40.3 ± 2.8 |

| 1:10 |

4.8 ± 0.6 |

52.3 ± 1.3 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).