1. Introduction

In biomechanical terms, stretching has been characterized by the authors team of Weerapong et. al., (2004). as a movement applied by an external and/or internal force – in order to increase muscle flexibility and to improve the joint range of motion (ROM) [

1]. The aim of stretching physical exercise is to increase muscle-tendon unit length and to improve joint flexibility, as well as to decrease the risk of soft tissue injuries [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

In our Review article we have examined and summarized the part of literature data related to the biomechanical characteristics and therapeutic effects of stretching on the main structural and functional unit: “muscle - tendon - ligament – joint”.

2. Topics and Results

2.1. Biomechanical parameters, healing and therapeutic effects of stretching.

Interesting results arose from recent numerous investigations and various stretching programs applied in the medical practice and sports. Biomechanical parameters and therapeutic effectiveness of stretch applications could modify joint, tendon and muscle flexibility. For the purpose, different variables, as collagen and elastin synthesis, fiber elongation and elasticity, energy absorption, etc., could be used as mechanobiological, cellular and molecular biomarkers.

A great number of retrospective and prospective studies have been performed and stratified on the acute and chronic effects of stretching - in physiological conditions and in pathological states. Progressive static stretching is effective during the prophylaxis of injuries in sports and exercise-training [

8,

9,

10]. The healing properties of stretching are of importance in the prophylaxis and treatment of joint injuries, soon combined with other rehabilitation procedures (massage, heat/cold, warming up, etc.) [

7,

11,

12,

13,

14] Recent studies reported high effectiveness of stretching in the treatment and prevention of contractures and fasciitis, as well as useful method for application in the routine orthopedic and traumatological practice [

5,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

As a rehabilitation method, stretching has been applied to improve biomechanical parameters of muscles, tendons, ligaments, fascia and joints [

4,

6,

7,

9,

20,

21].

The viscoelastic responses of muscles, tendons, ligaments, fascia and joints to the slow stretch could evaluate to the less passive tension, than a faster procedures [

22,

23]. The faster is stretch – the higher will be the muscle stiffness [

6]. Most stretching techniques (static-, ballistique-, etc.,) are successfully involved in the clinical practice [

2,

4,

24,

25].

The effects of stretching on the muscle- and joint flexibility are closely related to the joint range of motion (ROM): the increased range of motion induces the analgesic effects of stretching.

Various stretch techniques have been compared. Unfortunately, current results of the chronic effects of static stretching (SS) exercises on the muscle strength, flexibility, joint ROM and muscle power are still a matter of controversy [

5,

18,

26].

2.2. Animal, mathematical and computational models of stretching.

More scientific information is needed for creation of new successful mathematical and computational models of stretching [

27,

28].

The mathematical- and rheological models of joint cavity capsule and intra-articular synovial fluid turnover (viscosity, permeation of hyaluronan, glycosoaminoglycans - GAGs and albumin), indicated cellular mechanisms of stretch and a role of intercellular matrix as a selective molecular filter. The specific rheological properties of joint synovial fluid have been changed in traumatic and posttraumatic pathological states, different arthroses, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, etc.) [

29].

In the treatment and prevention of sport injuries, the static stretching (SS) is very important for efficient rehabilitation of joints, as well as in the development of improved sport programs for injuries prevention [

3,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Based on the last scientific findings and especially on biomechanical contributions in this field, new preventive and therapeutic measures – for avoiding stiffness and motion impairment in the joints, could be adopted during the early stages of diseases [

2,

9,

15].

The therapeutic effects of stretching have been established in a great number of experimental animal models (e.g. post-traumatic knee contractures in the rat and rabbit models, which have significance for humans) [

7,

35,

36,

37,

38]. Thus, it is possible to evaluate important data on cellular functions and intracellular matrix components of joint cartilage as well as information on the morphological structure and functions of joint capsules – in healthy controls and modified in the processes of contractures (post-traumatic, myogenic, arthrogenic, etc.) [

7,

11,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Zhang et al., (2018), examined effect of stretching, combined with ultrashort wave diathermy on joint functions and clarified its cellular mechanisms in a rabbit knee contracture model [

38]. Wang L., et al., (2022) [

7], studied the effects of different static progressive stretching durations on the knee joint range of motion, collagen- and alpha-actin expression in fibroblasts, as well as inflammatory cells number, and fibrotic changes in the joint capsule (as results of different static progressive stretching durations, applied in the post-traumatic knee contracture in the rat model). The authors concluded that the static progressive stretch could improve the post-traumatic knee contracture by increasing knee joint mobility.

Numerous animal models which simulate “knee flexion contracture”, and few modellings of “knee extension contracture”, have been proposed [

11]. The authors evaluated that “aggravation of contractures” correlated to the degree of “fibrosis response” of joints, related to activation of type I and type III collagen synthesis, as well as to stimulation of the pro-fibrotic gene expression in fibroblasts and chondroblasts. Proteomic analysis of the muscles and joint capsule has been performed by the same study group [

11]. The expression of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β-1) was also examined as a significant biomarker of changes in the synthesis and distribution of different collagen types (I-III) in the intercellular matrix. Important fact of clinical relevance is that the “extension contracture models” better mimic fracture and bed-associated immobilization of patients in traumatology, than the “flexion contracture models”.

The main question related to the stretching biomechanics is: “Could chronic stretching change the joint-ligament-tendon-muscle mechanical properties?” Effects were reported for joint resistance of stretch, muscle- and tendon stiffness, but a large heterogeneity was seen for most of the variables obtained [

4]. The same authors have analyzed 26 papers regarding longitudinal stretching (static, dynamic and/or PNF), in humans of any age- and different health status. Structural and mechanical variables were evaluated for joints and muscle-tendon units: dynamic stretching, static stretching, flexibility, stiffness, mechanical joint properties, muscle morphology and functional activities, changes in the tendon characteristics, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, etc. [

6]. Adaptations to chronic stretching protocols shorter than 8 weeks, seems to occur mostly at a sensory level [

6].

2.3. Biomechanical effects of the static- and active isometric stretching applied on the human knee joint

The effects of stretching on muscle properties are clearly described in the literature and depend on various factors, including stretching techniques, stretching time, retention time, rest time and the time difference between intervention and measurement [

28,

40,

41]. Most studies investigate the effects of static stretching on the passive properties of the muscle-tendon block [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. In a series of studies by Magnusson et al. [

42,

43,

45,

46,

47], was shown that the static stretching for 90 seconds at five repetitions reduced muscle resistance, passive stiffness, peak torque, and stress relaxation. Other team of researchers [

48,

49] concluded that changes in the viscoelastic properties of the muscle-tendon block depend more on the duration of stretching than on the number of stretches. An extension of static stretching time (from five to ten minutes), has been shown to reduce tendon stiffness, measured passively by ultrasonography [

48,

49]. The reduction in stiffness may be due to a change in the arrangement of collagen fibers in the tendon [

48]. Stretching increases the range of motion of the femoral flexion and the outer rotation [

21].

The isometric stretching is a type of static stretching associated with the resistance of muscle groups through isometric contractions of the stretched muscles. Due to the fact that this type of muscles stretching works in an isometric mode, the initiated muscle forces will affect the joints around which the muscles are located. The muscle forces produced by this type of stretching trigger processes within the joint itself. Cotofana et al. [

50] demonstrated that cartilage thickness decreases to 5.2% at a knee load with force equal to 50% of body weight. Herberthold et al. [

51] evaluated deformation at a force load equal to 150% body weight.

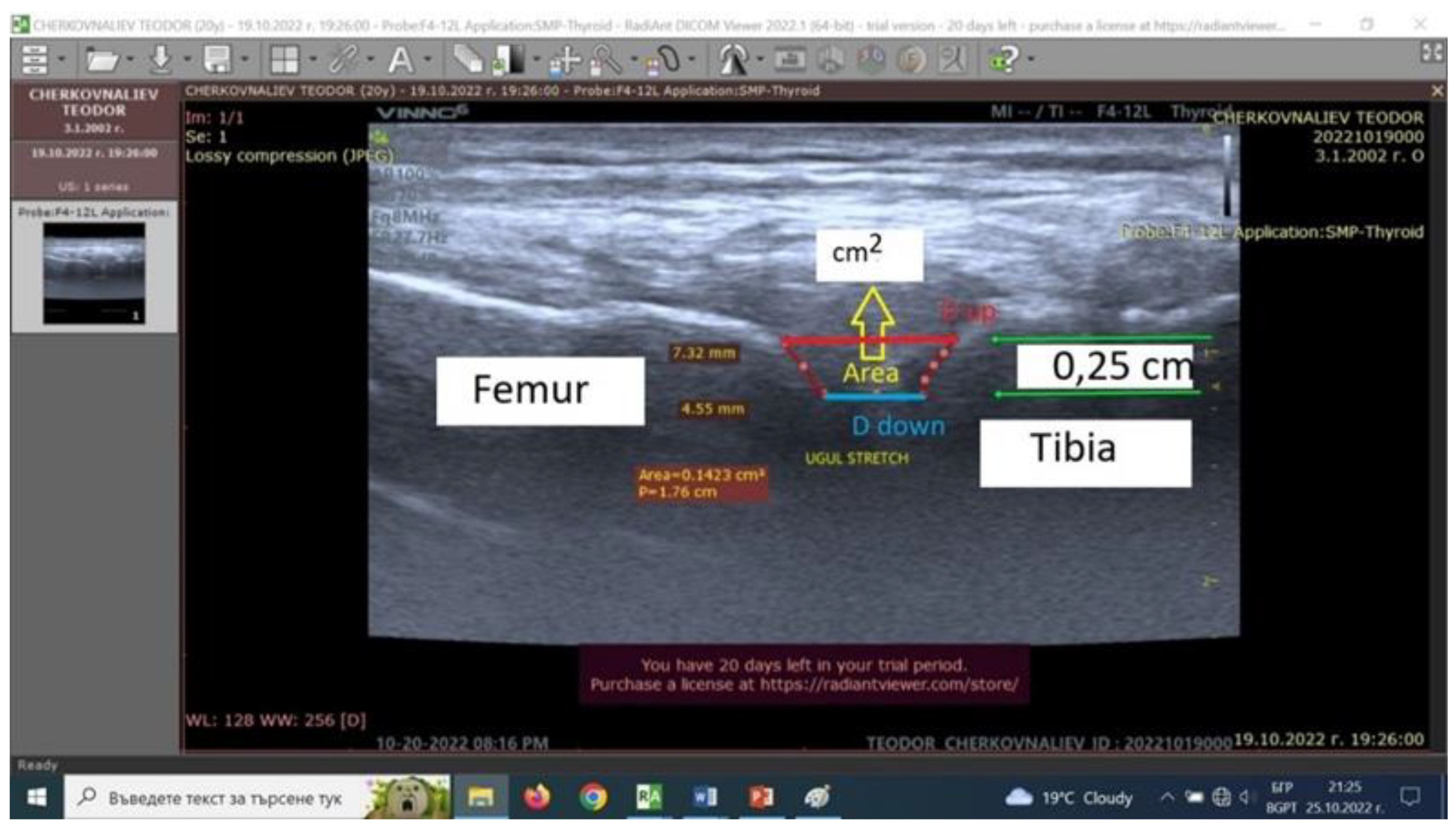

Our experimental model and working hypothesis estimated that as a result of active isometric stretching of the adjacent locomotor muscles, changes in the distance between the femur and the corresponding end of the tibia could be observed [

28]. The changes in the distance between two bones will in turn be conditioned by several factors: magnitude of the isometric muscle tension during stretching; duration and direction of the tension applied; tendon biomechanical properties as well as biomechanical properties of the knee joint (shape, size, viscosity of the synovial fluid, mechanical properties of the joint capsule elements).

Static investigations of the knee joint stability are often directed to stretching exercises [

28,

52,

53,

54,

56] and isometric back squat [

55].

Our study group experimental model for quantitative estimation of the biomechanical processes in human knee joint during active isometric stretching is based on knee joint capsule ultrasound scanning during isometric stretching exercises [

28,

52,

53,

56]. During the right lower limb pose with 140 degrees’ femur-tibia angle, the distance between the bones tibia and femur forming the knee joint was measured using ultrasound scanning. Our experimental model includes an ultrasound examination of a knee joint after isometric stretching of healthy men (n=10). The changes (in millimeters) of the distances between the femur and tibia were measured with portable ultrasound system (Vinno 6, China –

Figure 1). The apparatus was used for the purposes of our study in musculoskeletal mode, in real time with a scanning frequency of the linear transducer of 8 to 10 MHz. The system gives possibilities to work in three different upright positions – all with a femur-tibia angle of 140 degrees, at rest. In two of the three upright positions, extra loads of 4 and 8 kg were applied vertically down to the lower right limb to induce isometric stretching. Three quantitative parameters - distance up (Dup), distance down (Down), and area (A, cm

2) from ultrasound pictures were introduced (

Figure 1). They define two displacements (mm) and area (cm

2) between intraarticular femur and tibia cartilage surfaces.

The results obtained for the change of the intra-articular geometry under load and stretching could serve as a quantitative assessment of the internal joint kinematics and may determine the individual joint mobility of individual participants in the stretching exercises [

28,

52,

53,

56].

Тhe accuracy of ultrasound pictures and measurements in our experimental model is limited by three main components (

Figure 1)[

56]. The first is related to the transducer accuracy characteristics. The second depends to the accuracy in identity of the transducer-knee joint image position reproduction. The third component is determined by the researcher skill at pictures scan. The present preliminary experimental model accuracy is defined as a sum of the three components cited and is lower than 30%.

2.4. Biomechanical and biological (cellular and molecular) mechanisms of stretching

The cellular and molecular mechanisms, underlying the changes in joint flexibility, muscle strength and power are not well clarified in medicine and cell biology, thus need further investigations.

The additional effects of individual training status, age, sex, different pathological states, moderating the influences of stretch exercises on joints, muscles, tendons and ligaments, could be characterized as indirect [

6,

18,

22,

24,

35].

Stretching modulates the synthesis, deposition, concentration, degradation and distribution of collagen and glucosoaminoglycans (GAGs), affecting remodeling of the extracellular matrix [

57]. The data obtained encouraged the therapeutic application of stretch and stretching physiotherapy at the cellular and molecular levels – preliminary in the treatment and management of arthritic joints [

58].

The contributions of Bouffard et al., (2008) [

59] and Wang et al., (2022) [

7] demonstrated the importance of transforming growth factor β-1 (TGF β-1) in the collagen synthesis and extracellular matrix remodeling, after brief static stretch (SS) application. Simultaneously, stretching also modulate the aggrecan concentrations in the matrix. Xiong et al., 2017 [

60] examined the expression of TGF β-1, as a tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases.

TGF β-1 is one of the more important cytokines regulating fibroblast responses in the connective tissue – in health and diseases; collagen is a major protein in the extracellular matrix, aggrecan – main proteoglycan in articular cartilage. Stretching could be used to enhance and engineer connective tissue extracellular matrix with desirable collagen/elastin concentrations, improved elastic properties and regular mesenchymal cells (fibroblasts/chondroblasts) functions [

61].

Moreover, biomechanical aspects, underlying the different influences of active and passive stretch on joint, tendon, ligament and muscle flexibility rest are to be identified [

5,

26,

62]. The recent results in medical and sport scientific literature indicated that chronic SS exercises have potential to improve muscle strength and power [

5,

20]. Further investigations could examine the benefits of chronic SS exercises in old healthy and ill individuals, as compared to young, active and well-trained persons, as well as to professional athletes [

20,

30,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67].

2.5. Stretching is an integral component of mind-body exercises as Yoga (mainly Hatha Yoga), Tai chi and Gingong [64].

Gothe, McAuley et al. (2014, 2016) [

65,

67] compared functional benefits of stretching and yoga exercises. Four standard fitness tests assessing balance, strength, flexibility and mobility were administered [

64,

65]. Experimental stretching protocols varied with combinations of functional parameters: exercise duration, intensity frequency and whole body posture [

66]. Patel and colleagues (2012) concluded that yoga practice and stretch exercises lead to improvement of strength, flexibility, mobility and quality of life in older adults [

64]. Summarizing benefits of stretching and yoga exercises, the special sport programs in functional fitness could be adapted for elderly population of healthy individuals, as well as in cases of socially important diseases (arthrites, diabetes mellitus, chronic inflammation, etc.). Gothe and co-authors [

65,

67] recommended the effects of stretching and/or yoga exercises as improving functional fitness outcomes – in health and diseases, as well as for improvement of sport performance and health-related quality of life.

The potential preventive and therapeutic effects of static and yoga stretching (SS, YS) have been examined during different pathological states, like chronic inflammation, wound healing, tumor growth, etc., [

15,

66,

68,

69,

70].

The biological, cellular and molecular mechanisms, underlying anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer properties of stretching, yoga and TCC are very well summarized and presented in the review of Kròl et al., (2022) [

16]. These physical exercises could enhance the immune state, to change IL-6 and IL-10 levels and to improve health - related quality of life in older individuals [

71,

72,

73]. On the other hand, chronic inflammation may contribute to the initiation, progression and development of tumorigenesis [

74]. In these and other pathological states stretching exercises are recommended and included in programs - of Diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM-2) patients, in stroke and malignant diseases rehabilitation and treatment [

75,

76]. Stretching may serve as a method of connective tissue healing [

15,

77]. Ferreti and colleagues (2006) [

77] examined mechanical signals as strong anti-inflammatory and recommended use of mechanical forces of appropriate intensity in the rehabilitation of knee meniscus cartilage. Further studies are required to understand the role of collagen and aggrecan in the articular cartilage extracellular matrix remodeling and destruction (e.g. in osteoartritis of various etiologies). Collagen and the proteoglycan/aggrecan impaired syntheses is related to diseases as local and systemic (disseminated) sclerosis [

16]. The same authors pointed out that daily stretching may be a part of therapy in patients with systemic scleroses (SSc). Similar conclusions could be valid to the local contracture of Dupuitren (Morbus Dupuitren) [

25]. Guissard and Duchateau (2004) have studied the effects of static stretch training on the characteristics of the plantar-flexor muscles in 12 subjects. The improved muscle flexibility was associated (

r2 = 0.88;

P < 0.001) with a decrease in muscle passive stiffness. Although the changes in flexibility and passive stiffness were partially maintained 1 month after the end of the training program, reflex activities had already returned to control levels. It is concluded that the increased flexibility results mainly from reduced passive stiffness of the muscle–tendon unit and tonic reflex activity [

25].

In only one study [

78], a mouse breast cancer model was presented and the results showed slower tumor growth (from 2-4 weeks) under stretch influence.

Comparing various stretching techniques to study their short- and long-term effects on different parameters (knee joint ROM, hamstring flexibility, muscle electromyographic activity, etc.), the researchers have registered significant results preliminary for both parameters – joint ROM and hamstring flexibility [

79]. The same authors applied static stretching (SS) as a variant of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation contact relax techniques (PNF – CR). Knee range of motion (ROM), hamstring flexibility and knee flexor muscle electromyografic (EMG) activity have been also investigated [

3,

79]. The results obtained demonstrated an immediate, as well as a long- term effects on the knee ROM and only a long-term effect on flexibility in the elderly. Aging human population has exhibited an increase in muscle stiffness, as well as disturbances in the synthesis of types I – III collagen and alteration in ROM and EMG activities - due to the cellular and molecular processes in elderly [

3,

25,

30,

31,

63].

On the other hand, the PNF- CR and SS techniques are described as effective in increasing hamstring flexibility in young individuals [

31,

63,

79].

Ferber R. et al., (2002) [

3] applied three PNF stretch techniques: static stretch (SS), contact relax (CR) and agonist contact relax (ACR). The purposes of studies were to characterize effects of stretching on joints’ ROM and muscles’ EMG activity. The authors concluded that PNF stretch technique increase ROM in older adults. However, a paradoxal effect was also observed: PNF stretching may not induce muscular relaxation and to reduce muscle stiffness in older adults, due to age related alterations in the collagen synthesis and muscle elasticity [

3,

75,

80,

81].

Recent studies examined the combined effects of static and/or dynamic stretching, followed by foam rolling (FR) and other techniques - with or without local vibrations [

12,

32,

34,

38]. The combination of SS and FR is very effective and frequently used method in the sport programs and platforms - to increase ROM of joints and simultaneously to decrease muscle stiffness. In this relationship, it has been reported [

3,

82] that cell and tissue changes associated with aging are mainly related to a loss of joint range of motion (ROM), to increased muscle stiffness, as well as to pathological changes in the collagen and proteoglycans’ (GAGs) synthesis and metabolism.

3. Conclusions

Stretching therapy and prophylaxis include passive and active stretch techniques and some partner assisted methods precisely summarized in [

83].

In this review paper we have briefly described international and our study group experience in application of stretching as very interesting field of theoretical and practical medicine, sport sciences and biomechanics. The accuracy and limitations of stretch therapeutic techniques have also been defined. We have paid special attention to the simultaneous biomechanical and healing effects of the static and/or active isometric stretching, applied also in our in vivo model on the human knee joint. Improving knee joint range of motion (ROM) and flexibility, we have confirmed the results by ultrasound measurements. The accuracy in stretch treatment applied, leads to the efficient short- and long-term results: high movement quality and reduced risks of further joint soft tissue injuries in different pathological states, as well as in elderly and sports practice. Further investigations could continue to examine and compare healing, therapeutic and preventive effects of static stretching (SS) exercises, in different study groups; ill adult patients, old healthy individuals and young persons (well trained and physically active), as well as in a group of professional athletes.

From historical point of view and in present days, the benefits and main components of mind-body exercises like yoga (Hatha yoga) and stretching could be successfully applied in the special sport platforms and programs for stretch management, prophylaxis and treatment.

The therapeutic and preventive effects of stretching exercises have also been established in different experimental modelling systems: animal, computational and mathematical models, which have significance for human therapies and prophylaxis of injuries.

In addition to the static (passive) stretch, the authors characterized stretch therapy as combined application of wide range of techniques (e.g. stretching combined with foam rolling – with or without vibration, massage, motion movements, etc.). The conclusions of prevalent studies suggested that properly applied and combined with other techniques, stretch therapy could improve joint and muscle, fascia, tendon and ligaments health and flexibility, and resolve problems associated with joint and muscle stiffness. The prevention of sport injuries in a morpho-functional unit – joint, ligaments, tendon, muscles, could improve health and sports performance of healthy persons and professional athletes. In a long-term perspective, muscles increasing their flexibility and reducing their stiffness, lead to relaxation and muscle-fiber elongation – also related to best sport performance.

Main biomechanical variables and biomarkers at the cellular and molecular levels, such as collagen, elastin, hyaluronic acid and other glucosaminoglycans (GAGs) synthesis and localization in the joint and cartilage extracellular matrix, specific genes and TgF-β1 expression in the matrix, etc. need further investigations.

Combined stretch techniques proposed could be applied in efficient therapeutic programs in medicine and sports, depending on their short- and long-term healing effects.

Recent studies evaluated that the static progressive stretching (SPS) therapy, alone or in combined treatment, is the main way to improve the joint range of motion (ROM), to reduce or to prevent the development of arthrogenic contractures, joint capsule fibrosis and muscle stiffness, influencing positively the biological structures, functions, and biomechanics of the joint-ligaments-capsule-tendon-muscle unit. The therapeutic and preventive effects of static stretching (SS) need new clinical and sport applications. Further successful retrospective and prospective studies will elucidate stretching cellular, molecular and biomechanical mechanisms.

The static and/or dynamic stretching (SS, DS) applied in sports sciences, could improve joint and muscle properties adaptation, which is of great importance in prophylaxis and treatment in sports’ injuries.

However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms of stretching need further investigations.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, S.R., E.Z., E.K. and I.I., ; methodology, E. Z. and E. K.; software, E.K. and I.I..; validation, E.Z., E.K.; formal analysis, E.Z.; investigation, E.Z., E.K. and I.I.; resources, E.Z., E.K. and I.I.; data curation, A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.Z; writing—review and editing, E.Z and E.K.; visualization, E.K.,, I.I. and A.A.; supervision, E.Z., E.K. and I.I.; project administration, I.I.; funding acquisition, S.R. and I.I.

Funding

This research was funded by BULGARIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE FUND, grant number КП-06-Н57/18 from 16.11.2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” “Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Weerapong, P.; Hume, P.A.; Kolt, G.S. Stretching: Mechanisms and Benefits for Sport Performance and Injury Prevention. Phys. Ther. Rev. 2004, 9, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D. C.; Dalton JR, J. D.; Seaber, A. V.; Garrett JR, W. E. Viscoelastic properties of muscle-tendon units: the biomechanical effects of stretching. The American journal of sports medicine, 1990, 18, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferber, R.; Osternig, L.; Gravelle, D. Effect of PNF stretch techniques on knee flexor muscle EMG activity in older adults. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2002, 12, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, S.R.; Mendes, B.; Le Sant, G.; Andrade, R.J.; Nordez, A.; Milanovic, Z. Can chronic stretching change the muscle-tendon mechanical properties? A review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28, 794–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arntz, F.; Markov, A.; Behm, D.G.; Behrens, M.; Negra, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Moran, J.; Chaabene, H. Chronic Effects of Static Stretching Exercises on Muscle Strength and Power in Healthy Individuals Across the Lifespan: A Systematic Review with Multi-level Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 723–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudson, D. The biomechanics of stretching. Journal of Exercise Science and Physiotherapy, 2006, 2, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Cui, J.-B.; Xie, H.-M.; Zuo, X.-Q.; He, J.-L.; Jia, Z.-S.; Zhang, L.-N. Effects of Different Static Progressive Stretching Durations on Range of Motion, Myofibroblasts, and Collagen in a Posttraumatic Knee Contracture Rat Model. Phys. Ther. 2022, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsich, G.B.; Mueller, M.J.; A Sahrmann, S. Passive Ankle Stiffness in Subjects With Diabetes and Peripheral Neuropathy Versus an Age-Matched Comparison Group. Phys. Ther. 2000, 80, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, I.C.N.; Sartor, C.D. From treatment to preventive actions: improving function in patients with diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabetes/Metabolism Res. Rev. 2016, 32, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.B.; Brunt, D.; Tanenberg, R.J. Diabetic Neuropathy Is Related to Joint Stiffness during Late Stance Phase. J. Appl. Biomech. 2007, 23, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Q.-B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, F. Possible mechanism of static progressive stretching combined with extracorporeal shock wave therapy in reducing knee joint contracture in rats based on MAPK/ERK pathway. Bosn. J. Basic Med Sci. 2022, 23, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Konrad, A.; Kasahara, K.; Yoshida, R.; Murakami, Y.; Sato, S.; Aizawa, K.; Koizumi, R.; Wilke, J. The Combined Effect of Static Stretching and Foam Rolling With or Without Vibration on the Range of Motion, Muscle Performance, and Tissue Hardness of the Knee Extensor. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 37, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, D.M.; Cini, A.; Sbruzzi, G.; Lima, C.S. Influence of static stretching on hamstring flexibility in healthy young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiother. Theory Pr. 2016, 32, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukaya, T.; Sato, S.; Yahata, K.; Yoshida, R.; Takeuchi, K.; Nakamura, M. Effects of stretching intensity on range of motion and muscle stiffness: A narrative review. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2022, 32, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrueta, L.; Muskaj, I.; Olenich, S.; Butler, T.; Badger, G.J.; Colas, R.A.; Spite, M.; Serhan, C.N.; Langevin, H.M. Stretching Impacts Inflammation Resolution in Connective Tissue. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 231, 1621–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M.; Kupnicka, P.; Bosiacki, M.; Chlubek, D. Mechanisms Underlying Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Cancer Properties of Stretching—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Chang, N.-J.; Wu, W.-L.; Guo, L.-Y.; Chu, I.-H. Acute Effects of Foam Rolling, Static Stretching, and Dynamic Stretching During Warm-ups on Muscular Flexibility and Strength in Young Adults. J. Sport Rehabilitation 2017, 26, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, D. J.; Terry, M. E.; Haines, M. A.; Tabibnia, A. P.; Lyssanova, O. Effect of stretch frequency and sex on the rate of gain and rate of loss in muscle flexibility during a hamstring-stretching program: a randomized single-blind longitudinal study. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 2012, 26, 2119–2129. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, H.; Lauche, R.; Klose, P.; Lange, S.; Langhorst, J.; Dobos, G.J. Yoga for improving health-related quality of life, mental health and cancer-related symptoms in women diagnosed with breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD010802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D. Physical activity is medicine for older adults. Postgrad. Med. J. 2014, 90, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerapong, P.; Hume, P.A.; Kolt, G.S. Stretching: Mechanisms and Benefits for Sport Performance and Injury Prevention. Phys. Ther. Rev. 2004, 9, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataura, S.; Suzuki, S.; Matsuo, S.; Hatano, G.; Iwata, M.; Yokoi, K.; Tsuchida, W.; Banno, Y.; Asai, Y. Acute Effects of the Different Intensity of Static Stretching on Flexibility and Isometric Muscle Force. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 3403–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, A.; Gad, M.; Tilp, M. Effect of PNF stretching training on the properties of human muscle and tendon structures. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotta, K.; Behnke, B.J.; Arjmandi, B.; Ghosh, P.; Chen, B.; Brooks, R.; Maraj, J.J.; Elam, M.L.; Maher, P.; Kurien, D.; et al. Daily muscle stretching enhances blood flow, endothelial function, capillarity, vascular volume and connectivity in aged skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 1903–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guissard, N.; Duchateau, J. Effect of static stretch training on neural and mechanical properties of the human plantar-flexor muscles. Muscle Nerve 2003, 29, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middag, T.R.; Harmer, P. Active-isolated stretching is not more effective than static stretching for increasing hamstring ROM. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, S151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoichev, S. , Ivanov I., Ranchev S., Jotov I.. A review of the biomechanics of synovial joints with emphasize to static stretching exercise., Series on Biomechanics, 2021, vol 35, No 2, pp 3-20.

- 28. S. Ranchev, I. Ivanov, I. Iotov, St. Stoytchev, On the biomechanical processes in human knee joint during active isometric stretching, Series on Biomechanics, 2019, vol 33, No 3, ISSN 1313-2458, pp 56-61.

- Davies, D.V. Synovial membrane and synovial fluid of joints. Lancet 1946, 248, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryanton, M.; Bilodeau, M. The role of thigh muscular efforts in limiting sit-to-stand capacity in healthy young and older adults. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2017, 29, 1211–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, K.J.; Robinson, K.P.; Cuchna, J.W.; Hoch, M.C. Immediate Effects of Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation Stretching Programs Compared With Passive Stretching Programs for Hamstring Flexibility: A Critically Appraised Topic. J. Sport Rehabilitation 2017, 26, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-C.; Lee, C.-L.; Chang, N.-J. Acute Effects of Dynamic Stretching Followed by Vibration Foam Rolling on Sports Performance of Badminton Athletes. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2020, 19, 420–428. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkonen, J.; Nelson, A.G.; Eldredge, C.; Winchester, J.B. Chronic Static Stretching Improves Exercise Performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 1825–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konrad, A.; Nakamura, M.; Paternoster, F.K.; Tilp, M.; Behm, D.G. A comparison of a single bout of stretching or foam rolling on range of motion in healthy adults. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2022, 122, 1545–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagiwara, Y.; Ando, A.; Chimoto, E.; Tsuchiya, M.; Takahashi, I.; Sasano, Y.; Onoda, Y.; Suda, H.; Itoi, E. Expression of Collagen Types I and II on Articular Cartilage in a Rat Knee Contracture Model. Connect. Tissue Res. 2010, 51, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Hildebrand, K.; Zhang, M.; Germscheid, N.M.; Wang, C.; A Hart, D. Cellular, matrix, and growth factor components of the joint capsule are modified early in the process of posttraumatic contracture formation in a rabbit model. Acta Orthop. 2008, 79, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokuda, K.; Yamanaka, Y.; Kosugi, K.; Nishimura, H.; Okada, Y.; Tsukamoto, M.; Tajima, T.; Suzuki, H.; Kawasaki, M.; Uchida, S.; et al. Development of a novel knee contracture mouse model by immobilization using external fixation. Connect. Tissue Res. 2022, 63, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.B.M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhong, H.Z.M.; Liu, Y. Effect of Stretching Combined With Ultrashort Wave Diathermy on Joint Function and Its Possible Mechanism in a Rabbit Knee Contracture Model. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2018, 97, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoytchev, S.; Nikolov, S. Effects of flow-dependent and flow-independent viscoelastic mechanisms on the stress relaxation of articular cartilage. Ser. Biomech. 2023, 37, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, P.J.; Stanley, S.N. Effect of passive stretching and jogging on the series elastic muscle stiffness and range of motion of the ankle joint. Br. J. Sports Med. 1996, 30, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnusson, S. Passive properties of human skeletal muscle during stretch manoeuvres. MedSci Sports Exerc, 1998, 8, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, S.P.; Simonsen, E.B.; Aagaard, P.; Sørensen, H.; Kjaer, M. A mechanism for altered flexibility in human skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 1996, 497, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, S.; Simonsen, E.; Dyhre-Poulsen, P.; Aagaard, P.; Mohr, T.; Kjaer, M. Viscoelastic stressrelaxation during static stretch in human skeletal muscle in the absence of EMG activity. MedSci Sports Exerc, 1996, 6, 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- Mcnair, P.J.; Dombroski, E.W.; Hewson, D.J.; Stanley, S.N. Stretching at the ankle joint: viscoelastic responses to holds and continuous passive motion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnusson, S.P.; Simonsen, E.B.; Aagaard, P.; Gleim, G.W.; McHugh, M.P.; Kjaer, M. Viscoelastic response to repeated static stretching in the human hamstring muscle. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 1995, 5, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, S.P.; Aagaard, P.; Larsson, B.; Kjaer, M.; Ives, S.J.; Andtbacka, R.H.I.; Kwon, S.H.; Shiu, Y.-T.; Ruan, T.; Noyes, R.D.; et al. Passive energy absorption by human muscle-tendon unit is unaffected by increase in intramuscular temperature. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 88, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, S.P.; Simonsen, E.B.; Aagaard, P.; Kjaer, M. Biomechanical Responses to Repeated Stretches in Human Hamstring Muscle In Vivo. Am. J. Sports Med. 1996, 24, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, K.; Kanehisa, H.; Fukunaga, T. Is passive stiffness in human muscles related to the elasticity of tendon structures? Eur J Appl Physiol, 2001, 85, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, K.; Kanehisa, H.; Fukunaga, T. Effects of resistance and stretching training programs on the viscoelastic properties of human tendon structures in vivo. J Physiol., 2002, 538, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotofana, S.; Eckstein, F.; Wirth, W.; Souza, R.B.; Li, X.; Wyman, B.; Graverand, M.-P.H.-L.; Link, T.; Majumdar, S. In vivo measures of cartilage deformation: patterns in healthy and osteoarthritic female knees using 3T MR imaging. Eur. Radiol. 2011, 21, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberhold, C.; Faber, S.; Stammberger, T.; Steinlechner, M.; Putz, R.; Englmeier, K.; Reiser, M.; Eckstein, F. In situ measurement of articular cartilage deformation in intact femoropatellar joints under static loading. J. Biomech. 1999, 32, 1287–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranchev, S.; Ivanov, I. M.; Yotov, I.; Stoytchev, S. Studies on paradox in the work of musculoskeletal system in isometric stretching. Journal of Applied Sports Sciences, 2020, (2), 80-90.

- Stoytchev, St.; Ivanov, I.; Ranchev, S.; Iotov, I. A review of the biomechanics of synovial joints with emphasize to static stretching exercise. Series on Biomechanics, 2021, Vol.35 No.2, 3-20.

- Kuntz, A.B.; Chopp-Hurley, J.N.; Brenneman, E.C.; Karampatos, S.; Wiebenga, E.G.; Adachi, J.D.; Noseworthy, M.D.; Maly, M.R. Efficacy of a biomechanically-based yoga exercise program in knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0195653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, T.B.; de Medeiros, J.A.; Dantas, P.M.S.; Neto, L.d.O.; Schwade, D.; Vieira, W.H.d.B.; Oliveira-Dantas, F.F. A comparison of muscle electromyographic activity during different angles of the back and front squat. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 2020, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikova, R.; Ivanov, I.; Hristov, O.; Markova, N.; Trenev, L.; Angelova, S. Detailed Investigation of Knee Biomechanics during Posture Maintenance while Applying Different Static Loadings on the Spine. Int. J. Bioautomation 2023, 27, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusharkh, H.A.; Reynolds, O.M.; Mendenhall, J.; Gozen, B.A.; Tingstad, E.; Idone, V.; Abu-Lail, N.I.; Van Wie, B.J. Combining stretching and gallic acid to decrease inflammation indices and promote extracellular matrix production in osteoarthritic human articular chondrocytes. Exp. Cell Res. 2021, 408, 112841–112841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhavan, S.; Anghelina, M.; Rath-Deschner, B.; Wypasek, E.; John, A.; Deschner, J.; Piesco, N.; Agarwal, S. Biomechanical signals exert sustained attenuation of proinflammatory gene induction in articular chondrocytes. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2006, 14, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffard, N.A.; Cutroneo, K.R.; Badger, G.J.; White, S.L.; Buttolph, T.R.; Ehrlich, H.P.; Stevens-Tuttle, D.; Langevin, H.M. Tissue stretch decreases soluble TGF-β1 and type-1 procollagen in mouse subcutaneous connective tissue: Evidence from ex vivo and in vivo models. J. Cell. Physiol. 2008, 214, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Berrueta, L.; Urso, K.; Olenich, S.; Muskaj, I.; Badger, G.J.; Aliprantis, A.; Lafyatis, R.; Langevin, H.M. Stretching Reduces Skin Thickness and Improves Subcutaneous Tissue Mobility in a Murine Model of Systemic Sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syedain, Z.H.; Tranquillo, R.T. TGF-β1 diminishes collagen production during long-term cyclic stretching of engineered connective tissue: Implication of decreased ERK signaling. J. Biomech. 2011, 44, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behm, D.G.; Blazevich, A.J.; Kay, A.D.; McHugh, M. Acute effects of muscle stretching on physical performance, range of motion, and injury incidence in healthy active individuals: a systematic review. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.O.; Medeiros, D.M.; Minotto, B.B.; Lima, C.S. Comparison between static stretching and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation on hamstring flexibility: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Physiother. 2018, 20, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.K.; Newstead, A.H.; Ferrer, R.L.; Md; Pt; Halsall, T. ; Werthner, P.; Forneris, T.; Gothe, N.P.; McAuley, E.; et al. The Effects of Yoga on Physical Functioning and Health Related Quality of Life in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2012, 18, 902–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gothe, N.P.; Kramer, A.F.; McAuley, E. The Effects of an 8-Week Hatha Yoga Intervention on Executive Function in Older Adults. Journals Gerontol. Ser. A 2014, 69, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Vergara, D.; Grabowska, W.; Yeh, G.Y.; Khalsa, S.B.; Schreiber, K.L.; Huang, C.A.; Zavacki, A.M.; Wayne, P.M. A systematic review of in vivo stretching regimens on inflammation and its relevance to translational yoga research. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0269300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gothe, N.P.; McAuley, E. Yoga Is as Good as Stretching–Strengthening Exercises in Improving Functional Fitness Outcomes: Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial. Journals Gerontol. Ser. A 2015, 71, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizza, F.X.; Koh, T.J.; McGregor, S.J.; Brooks, S.V. Muscle inflammatory cells after passive stretches, isometric contractions, and lengthening contractions. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 92, 1873–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.-Y.; Chou, C.-H.; Huang, H.-D.; Yen, M.-H.; Hong, H.-C.; Chao, P.-H.; Wang, Y.-H.; Chen, P.-Y.; Nian, S.-X.; Chen, Y.-R.; et al. Mechanical stretch induces hair regeneration through the alternative activation of macrophages. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danhauer, S.C.; Addington, E.L.; Cohen, L.; Sohl, S.J.; Van Puymbroeck, M.; Albinati, N.K.; Culos-Reed, S.N. Yoga for symptom management in oncology: A review of the evidence base and future directions for research. Cancer 2019, 125, 1979–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumi, K.; Ashida, K.; Nakazato, K. Repeated stretch–shortening contraction of the triceps surae attenuates muscle atrophy and liver dysfunction in a rat model of inflammation. Exp. Physiol. 2020, 105, 1111–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eda, N.; Ito, H.; Shimizu, K.; Suzuki, S.; Lee, E.; Akama, T. Yoga stretching for improving salivary immune function and mental stress in middle-aged and older adults. J. Women Aging 2018, 30, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Collet, J. P.; Lau, J. The effect of Tai Chi on health outcomes in patients with chronic conditions: a systematic review. Archives of internal medicine, 2004, 164, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Baby, D.; Rajguru, J. P.; Patil, P. B.; Thakkannavar, S. S.; Pujari, V. B. Inflammation and cancer. Annals of African medicine, 2019, 18, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, E.; Khademi-Kalantari, K.; Khalkhali-Zavieh, M.; Rezasoltani, A.; Ghasemi, M.; Baghban, A.A.; Ghasemi, M. The effect of functional stretching exercises on functional outcomes in spastic stroke patients: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2018, 22, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H. Effects of passive static stretching on blood glucose levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1463–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferretti, M.; Madhavan, S.; Deschner, J.; Rath-Deschner, B.; Wypasek, E.; Agarwal, S. Dynamic biophysical strain modulates proinflammatory gene induction in meniscal fibrochondrocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2006, 290, C1610–C1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrueta, L.; Bergholz, J.; Munoz, D.; Muskaj, I.; Badger, G. J.; Shukla, A. ; .. & Langevin, H. M. Stretching reduces tumor growth in a mouse breast cancer model. Scientific reports, 2018, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi, S.; Ahamad, A.; Fatima, A.; Ahmad, I.; Malhotra, D.; Al Muslem, W.H.; Abdulaziz, S.; Nuhmani, S. Immediate and Long-Term Effectiveness of Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation and Static Stretching on Joint Range of Motion, Flexibility, and Electromyographic Activity of Knee Muscles in Older Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautieri, A.; Passini, F.S.; Silván, U.; Guizar-Sicairos, M.; Carimati, G.; Volpi, P.; Moretti, M.; Schoenhuber, H.; Redaelli, A.; Berli, M.; et al. Advanced glycation end-products: Mechanics of aged collagen from molecule to tissue. Matrix Biol. 2017, 59, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, J.P. Araújo, V. L.; Leal, Â. M.; Serrão, P. R.; Perea, J. P.; Santune, A. H.; ... Salvini, T. F. Diabetes and peripheral neuropathy are related to higher passive torque and stiffness of the knee and ankle joints. Kinesiology 2022, 54, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. R.; Walker, J. M. Knee and elbow range of motion in healthy older individuals. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 1983, 2, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Page, P. Current concepts in muscle stretching for exercise and rehabilitation. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2012, 7, 109–19. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).