Submitted:

27 June 2023

Posted:

28 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Risk factors for HCC

2.1. Risk factors for HCC in the general population- focus on hepatitis virus, fatty liver disease

2.2. Risk factors for HCC in the thalassemia group: focus on hepatitis virus, fatty liver disease

2.3. Risk factors for HCC in the thalassemia group: focus on iron overload

3. Pathogenesis of iron overload and HCC

3.1. Iron and inflammation

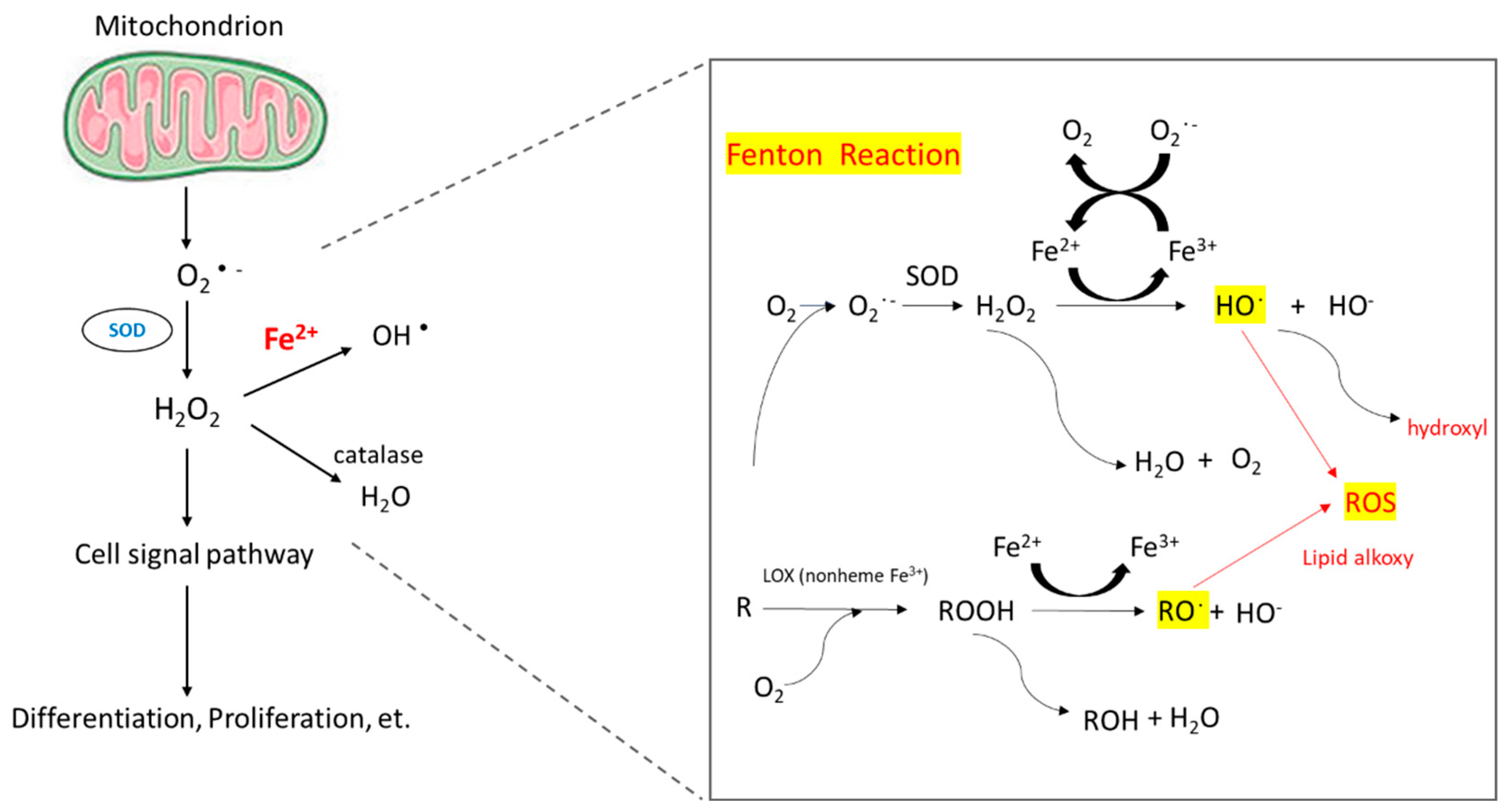

3.2. Iron and reactive oxygen species (ROS)

3.3. Hepcidin and ferriportin

4. Management

4.1. Management of iron overload

4.2. Management of HCC

5. Prognosis

6. Surveillance

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Steinberg, M. H., Forget, B. G., Higgs, D. R. & Weatherall, D. J. Disorders of hemoglobin: genetics, pathophysiology, and clinical management. (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

- Weatherall, D. J. The inherited diseases of hemoglobin are an emerging global health burden. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 115, 4331-4336 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Kattamis, A., Kwiatkowski, J. L. & Aydinok, Y. Thalassaemia. (2022).

- Modell, B. & Darlison, M. J. B. o. t. W. H. O. Global epidemiology of haemoglobin disorders and derived service indicators. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86, 480-487 (2008).

- Kattamis, A., Forni, G. L., Aydinok, Y. & Viprakasit, V. Changing patterns in the epidemiology of β-thalassemia. European Journal of Haematology 105, 692-703 (2020).

- Taher, A. T., Weatherall, D. J. & Cappellini, M. D. Thalassaemia. The Lancet 391, 155-167 (2018).

- Piel, F. B. & Weatherall, D. J. The α-thalassemias. New England Journal of Medicine 371, 1908-1916 (2014).

- Taher, A. T. & Saliba, A. N. J. H., the American Society of Hematology Education Program Book. Iron overload in thalassemia: different organs at different rates. Hematology , the American Society of Hematology Education Program Book 2017, 265-271 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Taher, A. T., Musallam, K. M. & Cappellini, M. D. J. N. E. J. o. M. β-Thalassemias. New England Journal of Medicine 384, 727-743 (2021).

- Kowdley, K. V. J. G. Iron, hemochromatosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 127, S79-S86 (2004).

- Mancuso, A., Sciarrino, E., Concetta Renda, M. & Maggio, A. A prospective study of hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in thalassemia. Hemoglobin 30, 119-124 (2006).

- Moukhadder, H. M., Halawi, R., Cappellini, M. D. & Taher, A. T. Hepatocellular carcinoma as an emerging morbidity in the thalassemia syndromes: a comprehensive review. Cancer 123, 751-758 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.-S., Lin, C.-L., Lin, C.-L. & Kao, C.-H. J. J. E. C. H. Thalassaemia and risk of cancer: a population-based cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health 69, 1066-1070 (2015).

- Taher, A., Musallam, K. & Cappellini, M. D. Guidelines for the Management of Non-Transfusion Dependent Thalassaemia (NTDT). (2017).

- Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 71, 209-249 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. h., Cheng, Y., Zhang, S., Fan, J. & Gao, Q. Changing epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia. Liver International 42, 2029-2041 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Sangiovanni, A. et al. Increased survival of cirrhotic patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma detected during surveillance. Gastroenterology 126, 1005-1014 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, P., Ott, P., Andersen, P. K., Sørensen, H. T. & Vilstrup, H. Risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Annals of internal medicine 156, 841-847 (2012).

- Lin, C.-W. et al. Heavy alcohol consumption increases the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B virus-related cirrhosis. Journal of hepatology 58, 730-735 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Sinn, D. H. et al. Alcohol intake and mortality in patients with chronic viral hepatitis: a nationwide cohort study. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 116, 329-335 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z. et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology 15, 11-20 (2018).

- Estes, C., Razavi, H., Loomba, R., Younossi, Z. & Sanyal, A. J. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology 67, 123-133 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Josep M. Llovet, R. K. K., Augusto Villanueva, Amit G. Singal, Eli Pikarsky, Sasan Roayaie, Riccardo Lencioni, Kazuhiko Koike, Jessica Zucman-Rossi & Richard S. Finn Hepatocellular carcinoma. nature reviews disease primers (2021).

- Borgna-Pignatti, C. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in thalassaemia: an update of the Italian Registry. British journal of haematology 167, 121-126 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Wonke, B., Hoffbrand, A., Brown, D. & Dusheiko, G. Antibody to hepatitis C virus in multiply transfused patients with thalassaemia major. Journal of clinical pathology 43, 638-640 (1990). [CrossRef]

- He, L.-N. et al. Elevated prevalence of abnormal glucose metabolism and other endocrine disorders in patients with-thalassemia major: a meta-analysis. BioMed research international 2019 (2019).

- Memaj, P. & Jornayvaz, F. R. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in type 1 diabetes: Prevalence and pathophysiology. Frontiers in Endocrinology 13, 1031633 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Pagani, A., Nai, A., Silvestri, L. & Camaschella, C. J. F. i. p. Hepcidin and anemia: a tight relationship. Frontiers in physiology 10, 1294 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Frey, P. A. & Reed, G. H. (ACS Publications, 2012).

- Muckenthaler, M. U., Rivella, S., Hentze, M. W. & Galy, B. J. C. A red carpet for iron metabolism. Cell 168, 344-361 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Hentze, M. W., Muckenthaler, M. U., Galy, B. & Camaschella, C. J. C. Two to tango: regulation of Mammalian iron metabolism. Cell 142, 24-38 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Grosse, S. D., Gurrin, L. C., Bertalli, N. A. & Allen, K. J. Clinical penetrance in hereditary hemochromatosis: estimates of the cumulative incidence of severe liver disease among HFE C282Y homozygotes. Genetics in Medicine 20, 383-389 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J. L. et al. Association of hemochromatosis HFE p. C282Y homozygosity with hepatic malignancy. JAMA 324, 2048-2057 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Turlin, B. et al. Increased liver iron stores in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma developed on a noncirrhotic liver. Hepatology 22, 446-450 (1995).

- Zanella, S., Garani, M. C. & Borgna-Pignatti, C. Malignancies and thalassemia: a review of the literature. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1368, 140-148 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Ruddell, R. G. et al. Ferritin functions as a proinflammatory cytokine via iron-independent protein kinase C zeta/nuclear factor kappaB–regulated signaling in rat hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology 49, 887-900 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Sindrilaru, A. et al. An unrestrained proinflammatory M1 macrophage population induced by iron impairs wound healing in humans and mice. The Journal of clinical investigation 121, 985-997 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Ringelhan, M., Pfister, D., O’Connor, T., Pikarsky, E. & Heikenwalder, M. J. N. i. The immunology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature immunology 19, 222-232 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Hoshida, Y. et al. Prognostic gene expression signature for patients with hepatitis C–related early-stage cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 144, 1024-1030 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Budhu, A. et al. Prediction of venous metastases, recurrence, and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma based on a unique immune response signature of the liver microenvironment. Cancer cell 10, 99-111 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Moeini, A. et al. An immune gene expression signature associated with development of human hepatocellular carcinoma identifies mice that respond to chemopreventive agents. Gastroenterology 157, 1383-1397. e1311 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Adams, P. C. J. T. A. j. o. g. Is there a threshold of hepatic iron concentration that leads to cirrhosis in C282Y hemochromatosis? The American journal of gastroenterology 96, 567-569 (2001).

- Angelucci, E. et al. Effects of iron overload and hepatitis C virus positivity in determining progression of liver fibrosis in thalassemia following bone marrow transplantation. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 100, 17-21 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S. J. & Stockwell, B. R. J. N. c. b. The role of iron and reactive oxygen species in cell death. Nature chemical biology 10, 9-17 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Moloney, J. N. & Cotter, T. G. in Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 50-64 (Elsevier).

- Choi, J.-E. et al. 15-Deoxy-Δ12, 14-prostaglandin J2 stabilizes hypoxia inducible factor-1α through induction of heme oxygenase-1 and direct modification ofprolyl-4-hydroxylase 2. Free radical research 50, 1140-1152 (2016).

- Cao, L., Liu, J., Zhang, L., Xiao, X. & Li, W. Curcumin inhibits H2O2-induced invasion and migration of human pancreatic cancer via suppression of the ERK/NF-κB pathway. Oncology reports 36, 2245-2251 (2016).

- Krause, A. et al. LEAP-1, a novel highly disulfide-bonded human peptide, exhibits antimicrobial activity. FEBS Lett 480, 147-150 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Park, C. H., Valore, E. V., Waring, A. J. & Ganz, T. Hepcidin, a urinary antimicrobial peptide synthesized in the liver. J Biol Chem 276, 7806-7810 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Pigeon, C. et al. A new mouse liver-specific gene, encoding a protein homologous to human antimicrobial peptide hepcidin, is overexpressed during iron overload. J Biol Chem 276, 7811-7819 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Ganz, T. Hepcidin, a key regulator of iron metabolism and mediator of anemia of inflammation. Blood 102, 783-788 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E. et al. Hepcidin, a putative mediator of anemia of inflammation, is a type II acute-phase protein. Blood 101, 2461-2463 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E. et al. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science 306, 2090-2093 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Kijima, H., Sawada, T., Tomosugi, N. & Kubota, K. Expression of hepcidin mRNA is uniformly suppressed in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 8, 167 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Tan, M. G. K. et al. Modulation of iron-regulatory genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma and its physiological consequences. Experimental Biology and Medicine 234, 693-702 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H. H. et al. Expression of hepcidin and other iron-regulatory genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma and its clinical implications. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 135, 1413-1420 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Kessler, S. M., Barghash, A., Laggai, S., Helms, V. & Kiemer, A. K. Hepatic hepcidin expression is decreased in cirrhosis and HCC. J Hepatol 62, 977-979 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Han, C. Y. et al. Hepcidin inhibits Smad3 phosphorylation in hepatic stellate cells by impeding ferroportin-mediated regulation of Akt. Nat Commun 7, 13817 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Joachim, J. H. & Mehta, K. J. Hepcidin in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer 127, 185-192 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. et al. Disordered hepcidin-ferroportin signaling promotes breast cancer growth. Cell Signal 26, 2539-2550 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Guo, W. et al. An important role of the hepcidin-ferroportin signaling in affecting tumor growth and metastasis. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 47, 703-715 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Rah, B., Farhat, N. M., Hamad, M. & Muhammad, J. S. JAK/STAT signaling and cellular iron metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma: therapeutic implications. Clinical and Experimental Medicine (2023). [CrossRef]

- Finianos, A., Matar, C. F. & Taher, A. J. I. j. o. m. s. Hepatocellular carcinoma in β-thalassemia patients: review of the literature with molecular insight into liver carcinogenesis. International journal of molecular sciences 19, 4070 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Hatairaktham, S. et al. Curcuminoids supplementation ameliorates iron overload, oxidative stress, hypercoagulability, and inflammation in non-transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia/Hb E patients. Annals of Hematology 100, 891-901 (2021).

- Mohammadi, E. et al. An investigation of the effects of curcumin on iron overload, hepcidin level, and liver function in β-thalassemia major patients: A double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Phytotherapy Research 32, 1828-1835 (2018).

- Al-Momen, H., Hussein, H. K., Al-Attar, Z. & Hussein, M. J. J. F. Green tea influence on iron overload in thalassemia intermedia patients: a randomized controlled trial. FResearch 9, 1136 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Saeidnia, M. et al. The Effect of Curcumin on Iron Overload in Patients with Beta-Thalassemia Intermedia. Clinical Laboratory 68 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Farmakis, D. et al. 2021 Thalassaemia International Federation Guidelines for the Management of Transfusion-dependent Thalassemia. HemaSphere 6 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Galle, P. R. et al. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of hepatology 69, 182-236 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J., Kelley, R. & Villanueva, A. J. P. A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. PubMed Article 7, 7 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Marrero, J. A. et al. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 68, 723-750 (2018).

- Borgna-Pignatti, C. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the thalassaemia syndromes. British journal of haematology 124, 114-117 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Borgna-Pignatti, C. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in thalassaemia: an update of the Italian Registry. British journal of haematology 167, 121-126 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, N. et al. Characteristics and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in multi-transfused patients with β-thalassemia. Experience of a single tertiary center. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology 12 (2020).

- Filippiadis, D. et al. Percutaneous Microwave Ablation for the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Transfusion-Dependent Beta-Thalassemia Patients. CardioVascular 45, 709-711 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ricchi, P. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with thalassemia in the post-DAA era: not a disappearing entity. Annals of Hematology 100, 1907-1910 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Maakaron, J. E., Cappellini, M. D., Graziadei, G., Ayache, J. B. & Taher, A. T. J. A. o. h. Hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis-negative patients with thalassemia intermedia: a closer look at the role of siderosis. Annals of hepatology 12, 142-146 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Restivo Pantalone, G. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with thalassaemia syndromes: clinical characteristics and outcome in a long term single centre experience. British journal of haematology 150, 245-247 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, A. & Perricone, G. J. B. J. o. H. Time to define a new strategy for management of hepatocellular carcinoma in thalassaemia? British Journal of Haematology 168, 304-305 (2015).

- Mangia, A. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in adult thalassemia patients: an expert opinion based on current evidence. BMC gastroenterology 20, 1-14 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Girardi, D. M. et al. Systemic Therapy for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Stand and Perspectives. Cancers 15, 1680 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Koulouris, A. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: an overview of the changing landscape of treatment options. Journal of hepatocellular carcinoma, 387-401 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Chan, S. L., Wong, N., Lam, W. J., Kuang, M. J. J. o. G. & Hepatology. Personalized treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma: Current status and Future perspectives. Journal of Gastroenterology 37, 1197-1206 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ding, J. & Wen, Z. J. B. c. Survival improvement and prognosis for hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of the SEER database. BMC cancer 21, 1-12 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Taher, A. T. & Cappellini, M. D. How I manage medical complications of β-thalassemia in adults. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 132, 1781-1791 (2018). [CrossRef]

- De Sanctis, V. et al. A concise review on the frequency, major risk factors and surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in β-thalassemias: past, present and future perspectives and the ICET-A experience. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology Infectious Diseases 12 (2020).

- Sheu, J.-C. et al. Growth rate of asymptomatic hepatocellular carcinoma and its clinical implications. Gastroenterology 89, 259-266 (1985). [CrossRef]

- Tzartzeva, K. et al. Surveillance imaging and alpha fetoprotein for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 154, 1706-1718. e1701 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P. J. et al. The Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using a Prospectively Developed and Validated Model Based on Serological BiomarkersDetection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers 23, 144-153 (2014).

- Schlosser, S. et al. HCC biomarkers–state of the old and outlook to future promising biomarkers and their potential in everyday clinical practice. Frontiers in Oncology 12 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Shahini, E. et al. Updating the Clinical Application of Blood Biomarkers and Their Algorithms in the Diagnosis and Surveillance of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Critical Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, 4286 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Foda, Z. H. et al. Detecting liver cancer using cell-free DNA fragmentomes. Cancer discovery 13, 616-631 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Tran, N. H., Kisiel, J. & Roberts, L. R. Using cell-free DNA for HCC surveillance and prognosis. JHEP Reports 3, 100304 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. et al. Ultrasensitive and affordable assay for early detection of primary liver cancer using plasma cell-free DNA fragmentomics. Hepatology 76, 317-329 (2022). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).