Submitted:

28 June 2023

Posted:

28 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.3. Mediation Model Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moffitt, T.E. Male antisocial behaviour in adolescence and beyond. Nat Hum Behav. 2018, 2, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, H.; Chiu, M. M.; Cui, Y.; Li, S.; Lu, M. Changes in aggression among mainland Chinese elementary, junior high, and senior high school students across years: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Aggress Violent Behav. 2019, 48, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.; Bushman, B.J. Human Aggression. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002, 53, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goemans, A.; E. Viding.; E. McCrory. Child Maltreatment, Peer Victimization, and Mental Health: Neurocognitive Perspectives on the Cycle of Victimization. TVA. 2021, 152483802110363. [CrossRef]

- Kassing, F.; Lochman, J. E.; Vernberg, E.; Hudnall, M. Using Crime Data to Assess Longitudinal Relationships Between Community Violent Crime and Aggressive Behavior Among At-Risk Youth. J Early Adolesc. 2022, 2022. 42, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yu, X.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. Attentional variability and avoidance of hostile stimuli decrease aggression in Chinese male juvenile delinquents. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2021, 15, 19–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China's Supreme People's Procuratorate releases White Paper on Juvenile Prosecutorial Work (2021). https://www.spp.gov.cn/spp/xwfbh/wsfbt/202206/t20220601_558766.shtml#1.

- Widom, C.S. , Does violence beget violence? A critical examination of the literature. Psychol Bull. 1989, 106, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousson, A. N.; Tajima, E. A.; Herrenkohl, T. I.; Casey, E. A. Patterns of Intimate Partner Violence and the Harsh Parenting of Children. J Interpers Violence. 2023, 38, 955–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, J. Harsh parenting and children's peer relationships: Testing the indirect effect of child overt aggression as moderated by child impulsivity. School Psychology International. 2019, 40, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Lan, X. The Associations of Parental Harsh Discipline, Adolescents’ Gender, and Grit Profiles With Aggressive Behavior Among Chinese Early Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, L. S.; Rabkin, A. N.; Emhoff, S. M.; Barry-Menkhaus, S.; Rivers, A. J.; Lehrbach, M.; Gordis, E. B. Childhood Harsh Parenting and Later Aggression: Non-violent Discipline and Resting Skin Conductance as Moderators. J Aggress Maltreat T. 2023, 32, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yang, Y.; Geng, J.; Cai, T.; Zhu, M.; Chen, T.; Xiang, J. Harsh Parenting and Children’s Aggressive Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. IJERPH. 2022, 19, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, N. R.; Dodge, K. A. Social information-processing mechanisms in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephanie,A., Godleski,a., Jamie,M.,Ostrov. (2020). Parental influences on child report of relational attribution biases during early childhood. JECP. 2020. 192. [CrossRef]

- Dillon, K. H.; Allan, N. P.; Cougle, J. R.; Fincham, F. D. Measuring Hostile Interpretation Bias: The WSAP-Hostility Scale. Assessment (Odessa, Fla.) 2016, 23, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, J. S.; Wagner, M. F.; Crouch, J. L. Reducing Child-Related Negative Attitudes, Attributions of Hostile Intent, Anger, Harsh Parenting Behaviors, and Punishment Through Evaluative Conditioning. Cogn Ther Res. 2017, 41, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perhamus, G. R.; Ostrov, J. M. Emotions and Cognitions in Early Childhood Aggression: the Role of Irritability and Hostile Attribution Biases. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2021, 49, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, K. A.; Greenberg, M. T.; Malone, P. S. Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Dev. 2008, 79, 1907–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mynard, H., & Joseph, S. Development of the multidimensional peer-victimization scale. Aggress Behav. 2000, 26, 169–178. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. C.; Ridenour, J. M.; Pitman, S.; Roche, M. Harsh Parenting Predicts Novel HPA Receptor Gene Methylation and NR3C1 Methylation Predicts Cortisol Daily Slope in Middle Childhood. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2021, 41, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Deng, X., & Du, X. Harsh parenting and academic achievement in Chinese adolescents: Potential mediating roles of effortful control and classroom engagement. J School Psychol. 2018, 67, 16–30. [CrossRef]

- Simons, R. L.; Whitbeck, L. B.; Conger, R. D.; Wu, C. Intergenerational transmission of harsh parenting. Dev Psychol. 1991, 27, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E. Y. H., & Li, J. Child Physical Aggression: The Contributions of Fathers’ Job Support, Mothers’ Coparenting, Fathers’ Authoritative Parenting and Child’s Theory of Mind. Child Ind Res. 2020, 13, 1085–1105.

- Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992, 63, 452–9. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, C.; Nie, Y.; Liu, Q. Parental Corporal Punishment, Peer Victimization, and Aggressive Adolescent Behavior: The Moderating Effect of Parent-Adolescent Relationship. J Child Fam Stud. 2022, 31, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, F.; Yang, R.; Zhu, W.; Wang, Y.; Gong, X.; Chen, Y.; Dong, Y.; Xia, L. The relationship between hostile attribution bias and aggression and the mediating effect of anger rumination. Pers Indiv Differ. 2019, 139, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes Hidalgo, A. P.; Thijssen, S., Delaney, S. W.; Vernooij, M. W.; Jansen, P. W.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J.; van IJzendoorn, M. H.; White, T.; Tiemeier, H. Harsh Parenting and Child Brain Morphology: A Population-Based Study. Child Maltreat. 2022, 27, 163–173. 27. [CrossRef]

- Perry, K. J.; Ostrov, J. M.; Shisler, S.; Eiden, R. D.; Nickerson, A. B.; Godleski, S. A.; Schuetze, P. Pathways from Early Family Violence to Adolescent Reactive Aggression and Violence Victimization. J Fam Viol. 2021, 36, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Wang, M.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z. Harsh Parental Discipline, Parent-Child Attachment, and Peer Attachment in Late Childhood and Early Adolescence. J Child Fam Stud. 2021, 30, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, M.; Wu, X.; Zhou, Z. Cognitive reactivity and emotional dysregulation mediate the relation of paternal and maternal harsh parenting to adolescent social anxiety. Child Abuse Neglect. 2022, 129, 105621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yu, X.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. Attentional variability and avoidance of hostile stimuli decrease aggression in Chinese male juvenile delinquents. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2021, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, A., Fegert, J. M., Rodens, K. P., Brähler, E., Lührs Da Silva, C., & Plener, P. L. The Cycle of Violence: Examining Attitudes Toward and Experiences of Corporal Punishment in a Representative German Sample. J Interpers Violence. 2021, 36, 263–286. [CrossRef]

- Brody, G. H., Yu, T., Beach, S. R. H., Kogan, S. M., Windle, M., & Philibert, R. A. Harsh parenting and adolescent health: A longitudinal analysis with genetic moderation. Health Psycholo. 2014, 33, 401–409. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Jiang, S. Violence exposure across multiple contexts as predictors of reactive and proactive aggression in Chinese preadolescents. Aggress Behav. 2022, 48, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M±SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Age | 16.57±0.61 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 2.DE | 0.96±0.42 | .1* | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 3.TOC | 0.05±0.23 | .01* | .01 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 4.COC | 1.03±0.21 | .08 | .05 | .25*** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 5.ITS | 3.63±2.61 | .14*** | .02 | -.10* | .12*** | 1 | |||||||||

| 6.AEP | 16.30±0.78 | .55** | .16** | .14*** | .03 | -.06 | 1 | ||||||||

| 7.SD | 0.37±0.48 | -.06 | -.02 | .05 | .02 | -.01 | -.01 | 1 | |||||||

| 8.FHP | 7.68±2.618 | -.004 | .05 | .14 | .16*** | -.02 | -.01 | .04 | 1 | ||||||

| 9.MHP | 6.92±2.518 | .00 | -.08* | .09* | .00 | -.03 | -.02 | .02 | .56*** | 1 | |||||

| 10.HAB | 46.43±9.848 | -.06 | .07 | -.01 | .01 | -.03 | -.07 | .03 | .14*** | .10* | 1 | ||||

| 11.PAB | 16.18±4.227 | .03 | -.02 | .07 | .00 | -.07 | .05 | -.01 | .25*** | .19*** | .26*** | 1 | |||

| 12.VAB | 13.15±3.091 | -.02 | .04 | .05 | -.05 | -.06 | .01 | -.04 | .18*** | .20*** | .19*** | .46*** | 1 | ||

| 13.PV | 5.96±1.831 | -.02 | .06 | .00 | -.02 | .02 | -.02 | .00 | .22*** | .21*** | .10* | .20*** | .23*** | 1 | |

| 14.RV | 15.50±4.617 | -.002 | .01 | -.05 | .05 | .03 | -.05 | .01 | .16*** | .19*** | .16*** | .17*** | .26*** | .43*** | 1 |

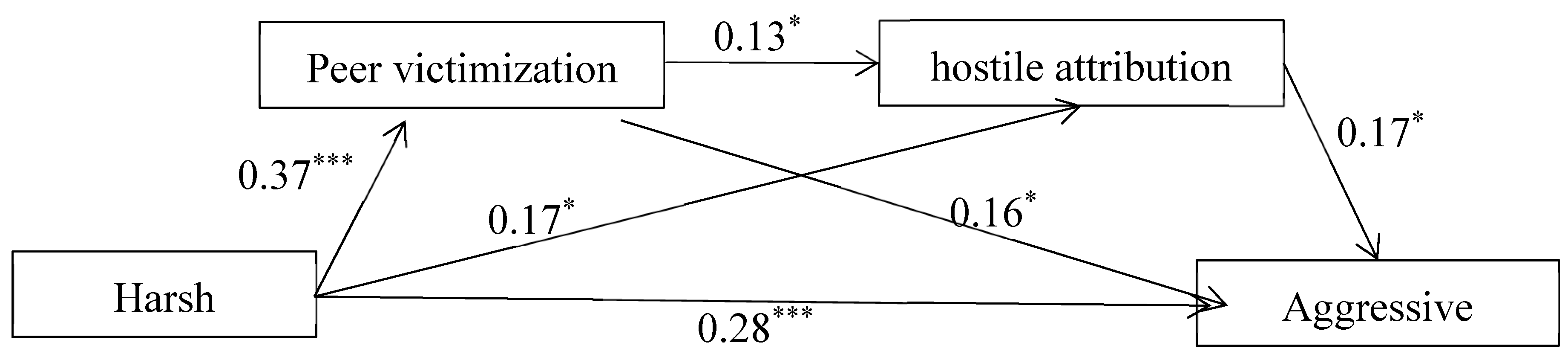

| Effect | β | p | 95%CI | Ratio of Total Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | ||||

| HP→AB | 0.28*** | <0.001 | [0.15,0.42] | 74.32% |

| Indirect Effect | ||||

| HP→PV→AB | 0.06* | <0.01 | [0.03,0.11] | 15.95% |

| HP→HAB→AB | 0.03* | <0.05 | [0.01,0.07] | 7.57% |

| HP→PV→HAB→AB | 0.01* | <0.05 | [0.002,0.02] | 2.16% |

| Total Mediation Effect | 0.10*** | <0.001 | [0.06,0.16] | 25.68% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).