Submitted:

20 July 2023

Posted:

21 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

- Bandura's social-cognitive theory and the interrelationship between significant others (not only the family), social influence and the influence of social support [37].

- -

- The Structural Model of Environmental Influences on Behaviour structures the complex influences of the environment at micro, meso, exo and macro levels [38].

- -

- The Ecological Model of Physical Activity - EMPA adds biological factors to the above models [39].

- -

-

- Biological and demographic variables such as gender, overweight, age or socio-economic status of the family.

- Psychological, cognitive and emotional variables such as self-efficacy and expected and expected benefits.

- Behavioural variables. For example, playing video games and surfing the Internet.

- Social and cultural variables, such as parental modelling and local traditions.

- Physical-environmental variables such as access to sports facilities; safe spaces, streets and parks.

2. Materials and Methods

- a)

- Children: 3-11 years old, attending one of the participant schools.

- b)

- Parents: having a son/daughter have participated in, at least, two of the ten KIA events.

- c)

- Sports managers: coach or manager of a sports organization; having participated in one of the KIA events (as organizer and/or trainer).

2.1. Sample description

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Data collection procedure

2.4. Data analysis

3. Results

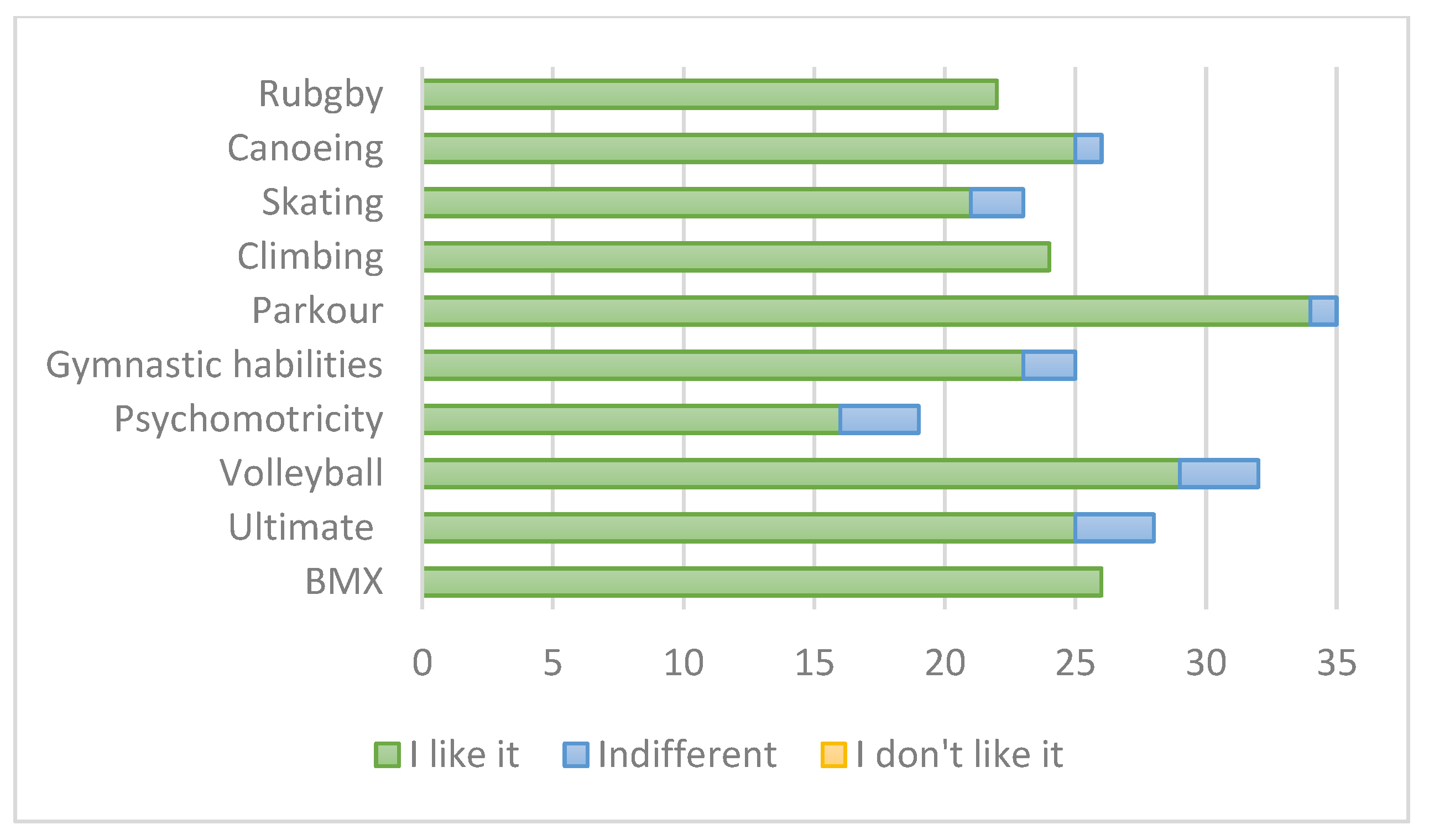

3.1. Children’s assessment of the programme.

3.2. Interviews’ results.

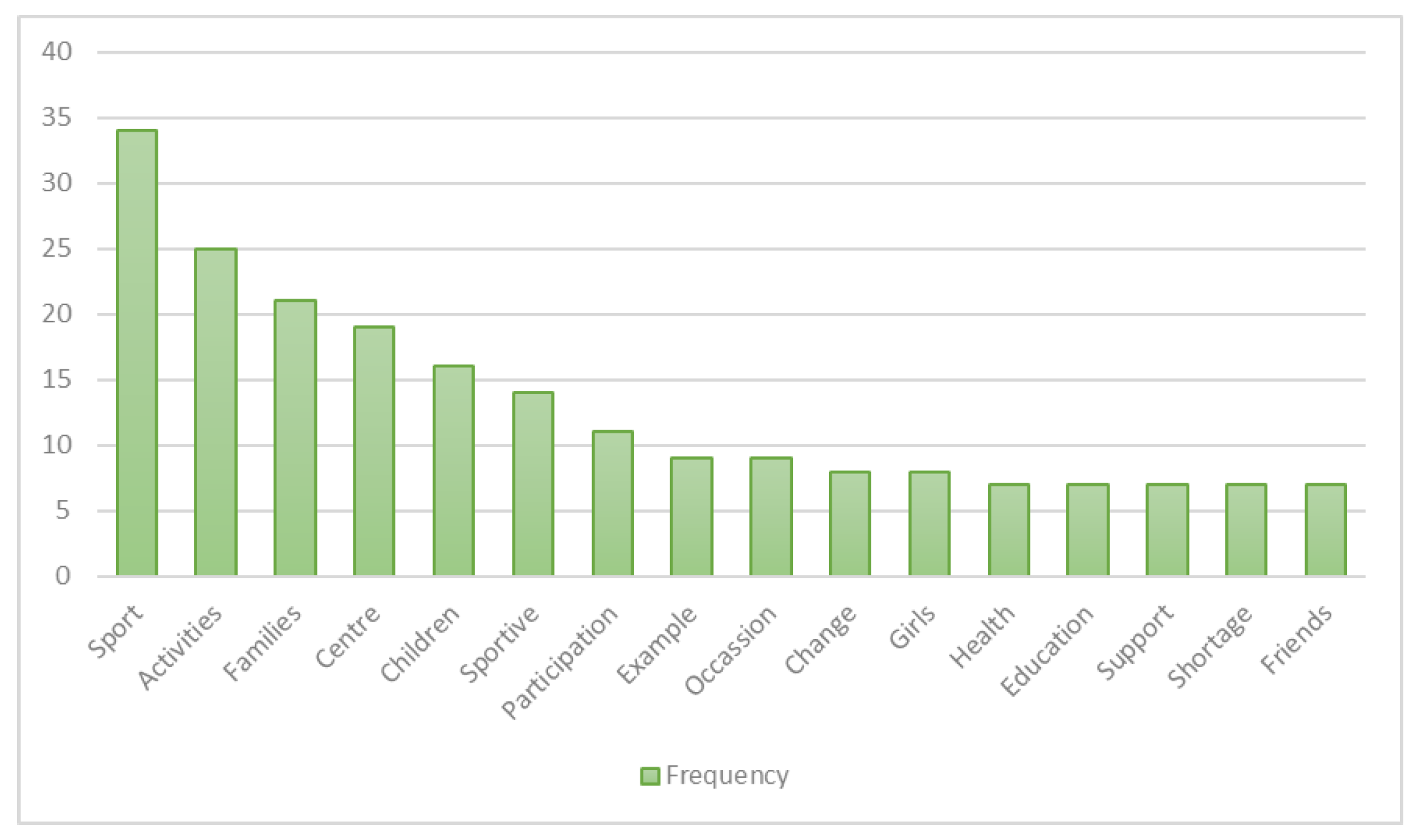

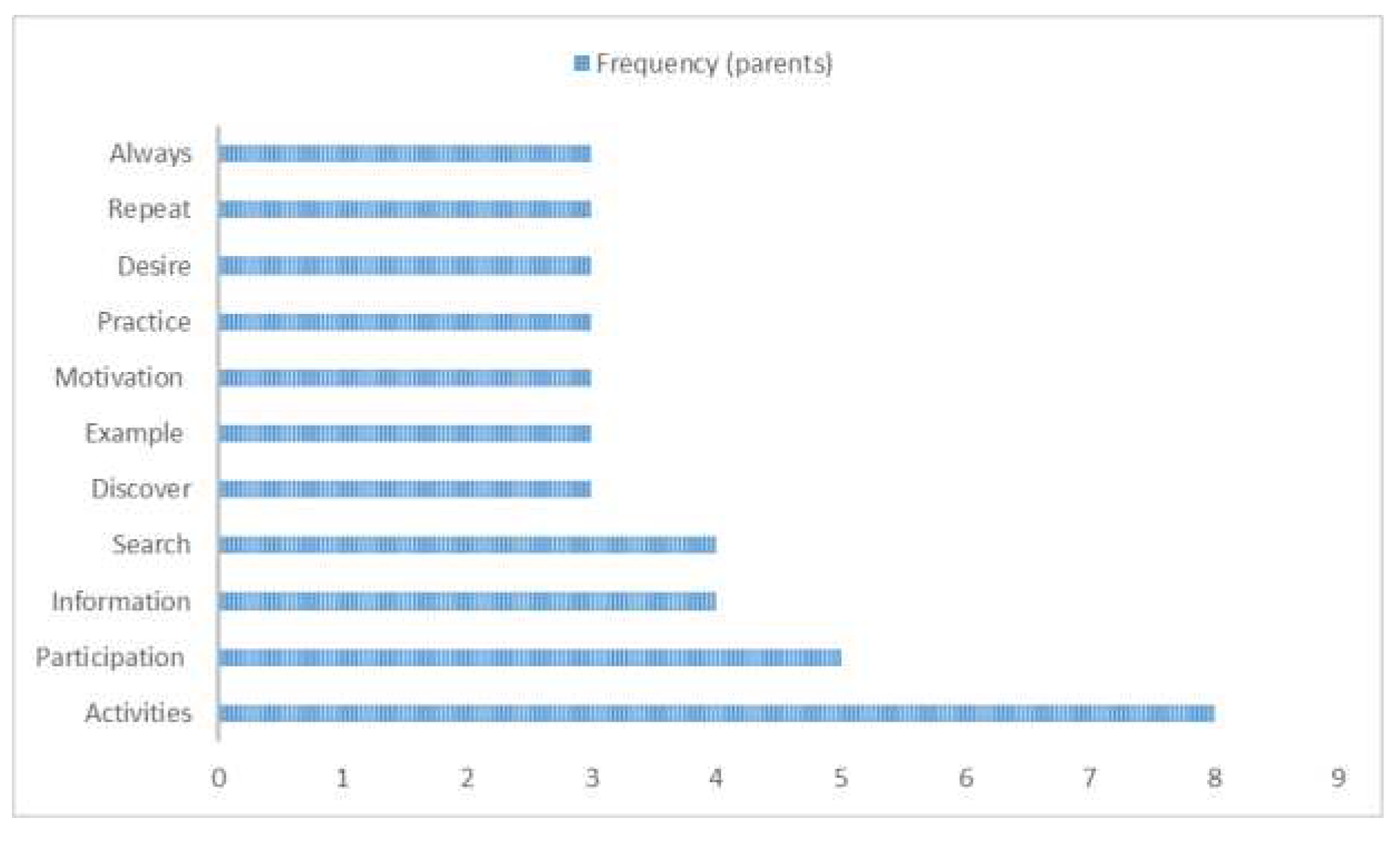

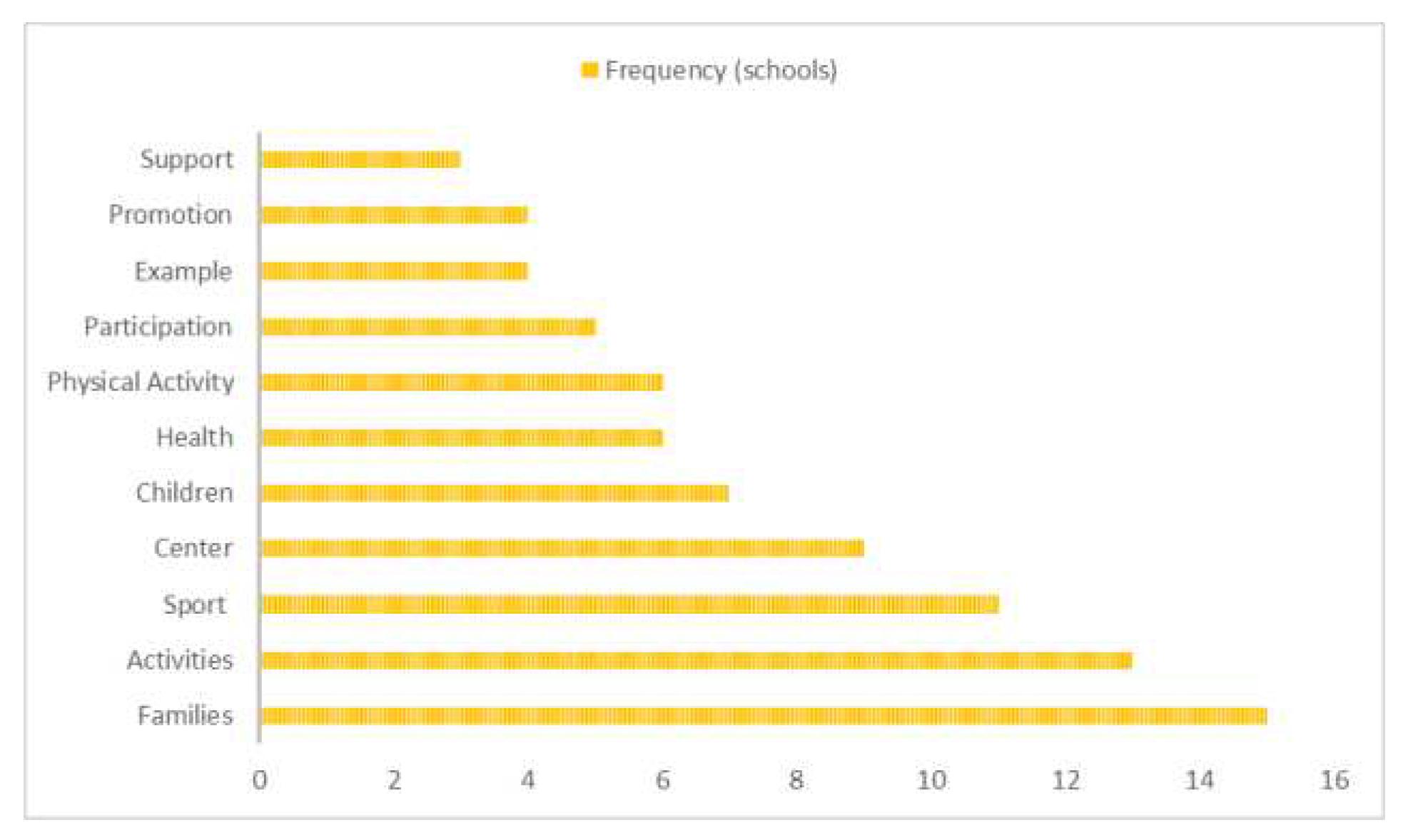

3.2.1. Thematic analysis.

- Links between the education system and the sport system.

…but the aim of introducing activities such as the KIA or other types of activities is for them to integrate them into their lives in later years, obviously as a state of physical and mental well-being for any person. So, of course, through the physical education area in the centre and through activities that can be carried out such as PIBA plans and KIA activities or the activity bank of the Government of Aragon. It is very clear.(D2)

- They encourage greater interest in sports in general.

- They have a certain transfer towards organised sport. For example, several of the participants showed an interest in joining associations and clubs in the sports they practise.

- Families also highlight their interest in continuing to practice in an unorganised way.

- However, some families show a low appreciation of sport as a form of family leisure (D4), which leads to low participation in this type of activity.

- a.

-

The educational center:

- To promote physical and emotional well-being;

- Inclusion;

- Diversity of activities (get to know);

- Four PE (Physical Education) sessions per week;

- Achieving long-term effects;

- Providing information on projects and activities;

- Involvement of the FE department;

- Dissemination of activities and projects;

- Involvement with neighborhood associations (D3);

- Organizing, managing, and facilitating activities;

- Ensuring compatibility with schooling and different economic levels (D4).

- b.

-

Families:

- Initiation into practice;

- Accompany your children in activities;

- Logistical support;

- Facilitator;

- Role model: On the one hand, you have to be a role model for the children, on the other hand, you have to help them discover the range of possibilities and facilitate them on the path of physical activity (P3).

- c.

-

Sports associations:

- Comfort: Ease of scheduling, good technicians (D3);

- Sports Culture: The centers can show them the wide variety of sporting activities and their benefits. It is a field of experimentation that, in turn, can bring them closer to the nearest clubs or sports in the area where they are (P3);

- To transmit the values associated with the sport.

- d.

-

Local government:

- Financial support: Grants to clubs and continuous training for technicians (D3);

- Governance: Intelligent resource management (D4);

- Facilitators: Opportunity enablers (G1);

- Design and maintenance: Decent sports areas (G2).

- 2.

- Local sports practice.

- The children’s desire to continue practicing;

- The desire to show their friends and colleagues what they have learned in the workshop;

- The desire to repeat similar experiences.

I have tried to find any time in the park or wherever to repeat what they have learnt. With friends, at school… they are looking to see how to develop a little bit more what they learnt in that hour, hour and a half of practice(P1)

…because even though we lived very close, we didn’t know that you could, that you could do particular activities. We also discovered that we knew that it was there…(P2)

- Self-practice (affordable and easily accessible materials, practice without materials, or adapted materials);

- Taking advantage of “time-outs” to continue practicing;

-

The families also highlight the “recovery” of Saturdays that the project has meant for them to accompany their children to the workshops, something they consider very valuable, especially in the post-COVID-19 period, due to:

- ○

- Less screen time for children when they leave the house for a morning of sport;

- ○

- Discovering new playful and healthy ways to spend a Saturday morning.

…because in my daughter’s case, at least, she has discovered that on Saturday mornings you can do other activities than drinking vermouth and playing computer games at home(P2)

- Known environment (G1), as activities in areas that are familiar to children;

- Facilitates activity, as it is convenient to practice close to home or school;

- Family reconciliation, at a time when quality family convivial moments are becoming increasingly scarce: Facilitates adherence, close social relations;

- Improving children’s autonomy: independence of children (facilitates reconciliation between siblings if they can go alone to train for example) (D3);

- A way to occupy active and healthy weekends;

- Lower investment of time and money (G1);

- Potential to take place during or outside school hours, reinforcing its impact;

- Prioritizing physical activity as a health and well-being factor;

-

Promoting a change of habits:

- ○

- Offering more alternatives;

- ○

- Allowing children to practice at their own risk;

- ○

- The novelty of new and less popular sports increases motivation.

- 3.

- Prevention of physical activity dropout in the transition from primary to secondary education.

- Prioritization of activities. One of the teachers points out that, for the first time in decades, at her school, they have noticed a decrease in extracurricular sports activities and an increase in cultural and scientific activities.

…And then obviously the increase in the use of screens, that is clear, but we have indeed started to notice that from the third year of primary school onwards there is a greater sedentary lifestyle, mainly for this reason. And perhaps also because of an excess of complementary activities that are not physical, such as English, music theory, Chinese…I mean, this overload sometimes leads to what is not there, in other words, there is much more cultural activity but less sporting activity.(D2)

- Time availability.

…because you have to take them to places, you don’t play mainly in the street like you used to.(D2)

- Possibility of accompaniment.

…the promotion of family activities far from generating greater involvement I believe that it excludes pupils who cannot be accompanied.(D1)

- Possibility of collaboration with other families.

It is clear that it is inherent, i.e., if a child cannot be accompanied by his or her family, it is difficult to carry out the activity.(D2)

- AFD facility in the same center. Also, families sometimes see sports as incompatible with studies (D4).

-

Increased academic burdens/demands:

- ○

- This is not the only reason for the increase in sedentary lifestyles;

- ○

- Change in interests.

The changes experienced in adolescence. Especially in girls who take on female cultural roles in which sport is left out.(D4)

- ○

- Need for advice or “guidance”;

- ○

- Need for socio-educational support.

- Loss of healthy PA habits;

- Motivation on the part of families.

For children with very sporty parents or who value sport a lot, perhaps not so much…. or for those who excel early, then the family is normally willing to make the effort…especially if it is in sports such as tennis or football… but with those who are there, on average, it depends a lot on the culture and the value they give to the sport. Or to their comfort because of course, you have to take them, go and pick them up… wait there, matches…;(G4)

- Also, the predominance of competitive sports, as

I believe that there is too much early specialisation, which leads to the abandonment of sports as early as the second stage of school.(G1)

Children either do competitive sports or they don’t do it at all. Playing in the street, in the park, etc., is being lost;(G4)

- Lack of financial resources;

- Peer group.

- 4.

- Strategies to promote healthy physical activity in childhood.

A physical education teacher is not enough. I think there is a lack of personal and material support. If there were neighborhood coordinators, I mean, that is one thing that could benefit the link that we could have between families, students, teachers, children, and sports.(D2)

- Scarcity of resources: Yes, but each family must adapt the resources to their characteristics. There is a lot of variety to choose from and every family can get adequate physical activity (D4);

- Inequalities in the possibility of accompaniment and lack of family support;

- Peer group;

- Family overprotection;

- “Need” to take them to facilities instead of playing in the street;

- Lack of nearby sports facilities;

- Increased screen time;

- COVID standstill;

- Increasing sedentary behavior at younger ages (from 3rd grade onwards): Children should play and move much more (P3);

- Increase in non-physical cultural extracurricular activities;

- Activity overload;

- Lack of staff in the centers:

…support of some kind, socio-educational, I don’t know exactly how it could be, but what is important is what is achieved in primary school because obviously, children in primary school are a movement in themselves. But it is a pity that those habits, especially health habits, are lost in a significant percentage;(D2)

- Lack of material in the centers;

- “Loneliness” of the teacher with an interest in promotion;

- Possibility of neighborhood coordinators;

- Complex communication between families, pupils, and teachers;

- Children and sports;

- Established routines that make it difficult for families to change;

- Little offer of minority sports;

- Limited choice of opening hours and facilities, as well as inequalities between neighborhoods (G1);

- Time: …the biggest barrier is often time, so some are very much in favor of and seek the time, but those who don’t have the time don’t bother to make time for it either (D1).

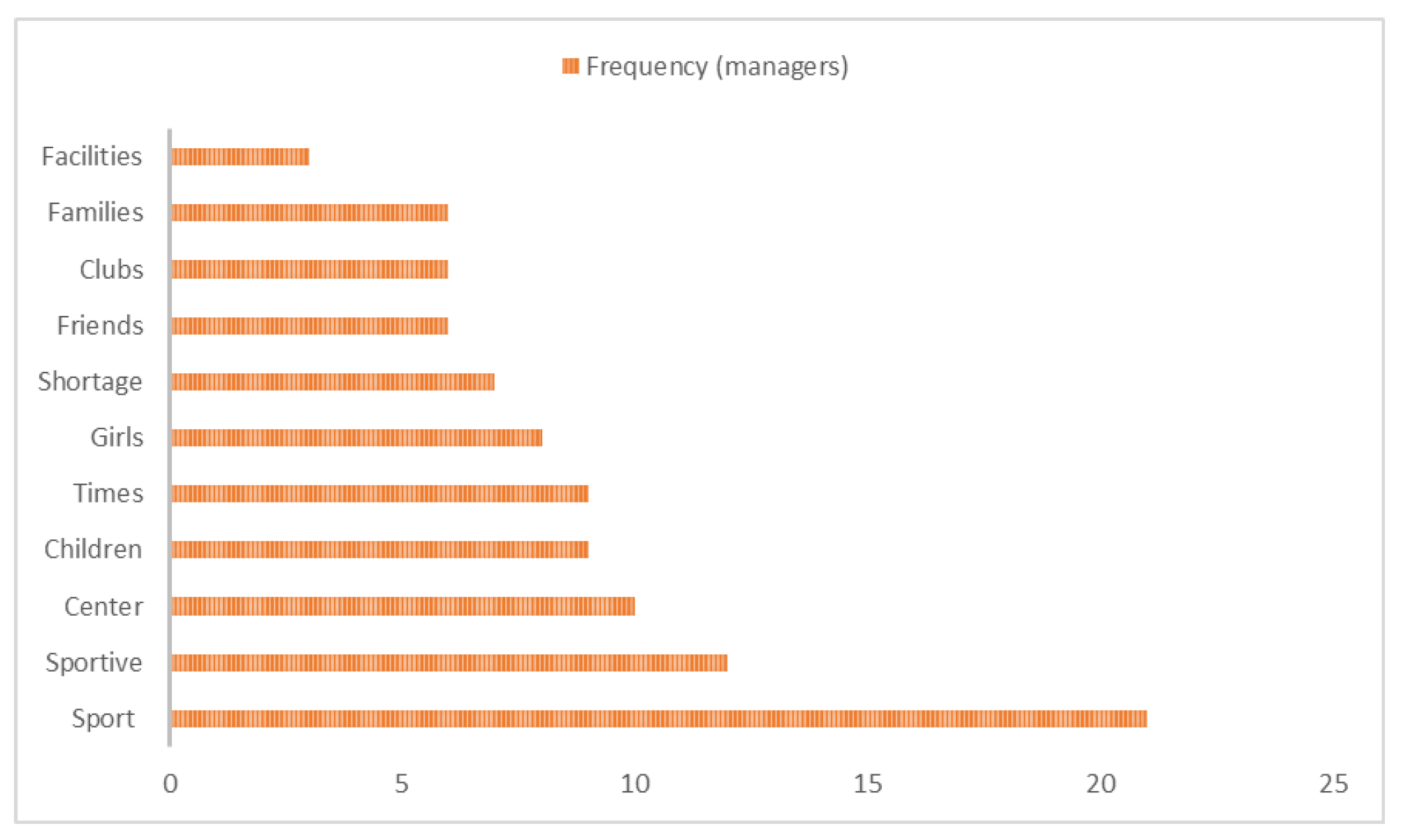

3.2.2. Highlihted concepts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MacKenzie, J.; Brunet, J.; Boudreau, J.; Iancu, H.D.; Bélanger, M. Does proximity to physical activity infrastructures predict maintenance of organized and unorganized physical activities in youth? Prev. Med. Rep. 2015, 2, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consejo Superior de Deportes. Los Hábitos Deportivos de la Población Escolar en España. Available online: https://redined.educacion.gob.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11162/66767/00820122017247.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Soler-Lanagrán, A.; Castañeda-Vázquez, C. Estilo de vida sedentario y consecuencias en la salud de los niños. Una revisión sobre el estado de la cuestión. J. Sport Health Res. 2017, 9, 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, S.; Buoncristiano, M.; Gelius, P.; Abu-Omar, K.; Pattison, M.; Hyska, J.; Duleva, V.; Musić Milanović, S.; Zamrazilová, H.; Hejgaard, T.; et al. Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Sleep Duration of Children Aged 6–9 Years in 25 Countries: An Analysis within the WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI) 2015–2017. Obes. Facts 2021, 14, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, J.L.; Cachón, J.; Lara, A.; Zagalaz, M.L. Influence of physical activity in the quality of life of children 10 and 11 years. J. Sport Health Res. 2016, 8, 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Babey, S.H.; Wolstein, J.; Diamant, A.L. Few California Children and Adolescents Meet Physical Activity Guidelines. Policy Brief 2018, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, M.; Stewart, T.; Marek, L.; Duncan, S.; Campbell, M.; Kingham, S. Health-promoting and health-constraining environmental features and physical activity and sedentary behaviour in adolescence: A geospatial cross-sectional study. Health Place 2022, 77, 102887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, G.R.; Giles-Corti, B.; Bulsara, M. The relationship between destination proximity, destination mix and physical activity behaviors. Prev. Med. 2008, 46, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casado-Robles, C.; Viciana, J.; Guijarro-Romero, S.; Mayorga-Vega, D. Conocimiento del entorno para la práctica de actividad física en escolares (CEPAF): Desarrollo y validación de una prueba escrita objetiva de elección múltiple. J. Sport Health Res. 2021, 13, 223–244. [Google Scholar]

- Neshteruk, C.D.; Jones, D.J.; Skinner, A.; Ammerman, A.; Tate, D.F.; Ward, D.S. Understanding the Role of Fathers in Children’s Physical Activity: A Qualitative Study. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, R.R.; Dowda, M.; Dishman, R.K.; Colabianchi, N.; Saunders, R.P.; McIver, K.L. Change in Children’s Physical Activity: Predictors in the Transition from Elementary to Middle School. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, e65–e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlugonski, D.; DuBose, K.D.; Habeeb, C.M.; Rider, P. Physical Activity Coparticipation Among Parent–Young-Child Dyads. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2020, 32, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kippe, K.O.; Fossdal, T.S.; Lagestad, P.A. An Exploration of Child–Staff Interactions That Promote Physical Activity in Pre-School. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 607012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A.R.; Goodman, A.; Page, A.S.; Sherar, L.B.; Esliger, D.W.; van Sluijs, E.M.; Andersen, L.B.; Anderssen, S.; Cardon, G.; Davey, R.; et al. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in youth: The international children’s accelerometry database (ICAD). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonge, K.L.; Jones, R.A.; Okely, A.D. The relationship between educators’ and children’s physical activity and sedentary behaviour in early childhood education and care. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2021, 24, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, S.; Gu, X. Home- and Community-Based Interventions for Physical Activity and Early Child Development: A Systematic Review of Effective Strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cervero, R.B.; Ascher, W.; Henderson, K.A.; Kraft, M.K.; Kerr, J. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.R.L.; Bredahl, T.V.G.; Elmose-Østerlund, K.; Hansen, A.F. Motives and Barriers Related to Physical Activity within Different Types of Built Environments: Implications for Health Promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.P.; Zheng, J.K. Proximity to an exercise facility and physical activity in China. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2014, 45, 1483–1491. [Google Scholar]

- Bennàsser, M.; Vidal-Conti, J. Relación entre actividad física y características de la vivienda y su entorno en jóvenes. J. Sport Health Res. 2021, 13, 281–294. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Saiz, A.; Alonso, A.; Jiménez Martín, D.; Lamíquiz, P. Can Proximal Environments Prevent Social Inequalities Amongst People of All Ages and Abilities? An Integrative Literature Review Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Gao, M.; Luo, D.; Zhou, X. Effects of Children’s Outdoor Physical Activity in the Urban Neighborhood Activity Space Environment. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 631492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavand, K.A.; Cain, K.L.; Conway, T.L.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D.; Kerr, J.; Glanz, K.; Sallis, J.F. Associations between Neighborhood Recreation Environments and Adolescent Physical Activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2019, 16, 880–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, J.A.; Phillips, D.A. Relationships Between Physical Activity and the Proximity of Exercise Facilities and Home Exercise Equipment Used by Undergraduate University Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2005, 53, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, T.K.; Rundle, A.; Neckerman, K.M.; Sheehan, D.M.; Lovasi, G.S.; Hirsch, J.A. Neighborhood Recreation Facilities and Facility Membership Are Jointly Associated with Objectively Measured Physical Activity. J. Urban Health 2019, 96, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, D.; Connelly, M. Does Proximity to Activity-Inducing Facilities Explain Lower Rates of Physical Activity by Low-Income and Minority Populations? Transp. Res. Rec. 2011, 2264, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehl, R.; Thiel, A.; Nagel, S. Children’s sport opportunities and parental support in single-parent families with a lower socio-economic status. An ecological perspective. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2022, 20, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Valdivia, N.; Pérez-del-Pulgar, C.; de Bont, J.; Anguelovski, I.; López-Gay, A.; Pistillo, A.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Duarte-Salles, T. Residential Proximity to Urban Play Spaces and Childhood Overweight and Obesity in Barcelona, Spain: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo-Macias, J. Agro-food production and consumption in perimetropolitan areas. A typological approach from the proximity approach. Estudios Sociales. Rev. Aliment. Contemp. Desarro. Reg. 2019, 29, e19701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomà, R.; Ubasart, G. Vidas en transición. In (Re)Construir la Ciudadanía Social; Tecnos: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Resa, S. La fuerza de lo local y el ciclo corto refuerzan la atracción hacia los productos de proximidad. Distrib. Consumo 2021, 1, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Miralles-Guasch, C.; Marquet Sardà, O. Dinámicas de proximidad en ciudades multifuncionales. CyTET 2013, XLV, 501–510. [Google Scholar]

- Lavandinho, S. La proximidad, ¿un nuevo valor urbano? Monográfico Ciudad. 2014, 17, 21–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Análisis de los Hábitos, Demandas y Tendencias Deportivas de la Población Zaragozana 2015. Zaragoza Deporte. 2016. Available online: https://www.zaragozadeporte.com/Noticia.asp?id=3232 (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological models of human development. In Reading on the Development of Children; Gauvain, M., Cole, M., Eds.; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Moral, L. Theories and models that explain and promote physical activity in children and adolescents. Educ. Futuro 2017, 36, 177–208. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol. Health 1998, 13, 623–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachs, T.D. The Nature of Nurture; Individual Differences and Development; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1992; Volume 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J.C.; Lee, R.E. Toward a comprehensive model of physical activity. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 4, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Prochaska, J.J.; Taylor, W.C. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N. Ecological models of health behavior. Health Behav. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 5, 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lofland, J.; Snow, D.; Anderson, L.; Lofland, L.H. Analyzing Social Settings: A Guide to Qualitative Observation and Analysis; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport, Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, G.; Hayfield, N. Essentials of Thematic Analysis; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, G.E.J.; Buliung, R.N.; Flora, P.K.; Fusco, C. Active school transport, physical activity levels and body weight of children and youth: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2009, 48, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda-Balboa, M.J.; Huertas-Delgado, F.J.; Herrador-Colmenero, M.; Cardon, G.; Chillón, P. Parental barriers to active transport to school: A systematic review. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 65, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero-Solís, M.; Gallego, D.I.; Tapia-Serrano M, Á.; Pulido, J.J.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A. School-based Physical Activity Interventions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandbu, Å.; Bakken, A.; Stefansen, K. The continued importance of family sport culture for sport participation during the teenage years. Sport Educ. Soc. 2019, 25, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, A.; Zanutto, G.; Longo, G.; Marini, S.; Soldà, G.; Salussolia, A.; Anastasia, A.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Ceciliani, A.; Dallolio, L. Erasmus+sport let’s move Europa: Learning units for health promotion among children and adolescents. Eur. J. Public Health 2022, 32 (Suppl. 3), ckac131–ckac463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Boys | Girls | Age boys (yr.) X̅±SD | Age girls (yr.) X̅ ±SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| School 1 | 32 | 29 | 7.96±2.29 | 6.5±3.53 |

| School 2 | 8 | 5 | 7±2.44 | 7.33±2.54 |

| School 3 | 7 | 3 | 8.37±1.68 | 9.33±1.52 |

| School 4 | 17 | 22 | 8.23±1.92 | 6.68±2.80 |

| School 5 | 1 | 0 | 8 | - |

| School 6 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 10 |

| School 7 | 12 | 7 | 8±1.70 | 8±2.58 |

| Code | Category | Gender | Profiles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | P1 | Family | Woman | Mother |

| Participant 2 | P2 | Family | Man | Father |

| Participant 3 | P3 | Family | Woman | Mother |

| Participant 4 | D1 | Schools | Man | Director |

| Participant 5 | D2 | Schools | Woman | PE Teacher |

| Participant 6 | D3 | Schools | Man | PE Teacher |

| Participant 7 | D4 | Schools | Woman | Primary Teacher |

| Participant 8 | G1 | Sports | Woman | Coach |

| Participant 9 | G2 | Sports | Man | Manager |

| Participant 10 | G3 | Sports | Woman | Manager |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).