Submitted:

28 June 2023

Posted:

28 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Characteristics of judo

2.1. The philosophy of judo

2.2. Characteristics of judo as a hard martial art and an open-skill exercise

2.3. Characteristics of judo matches

2.4. Dynamics and energy demands of judo matches

2.5. Characteristics of judo-specific training modalities

3. Benefits of judo training for physical and cognitive function in the elderly

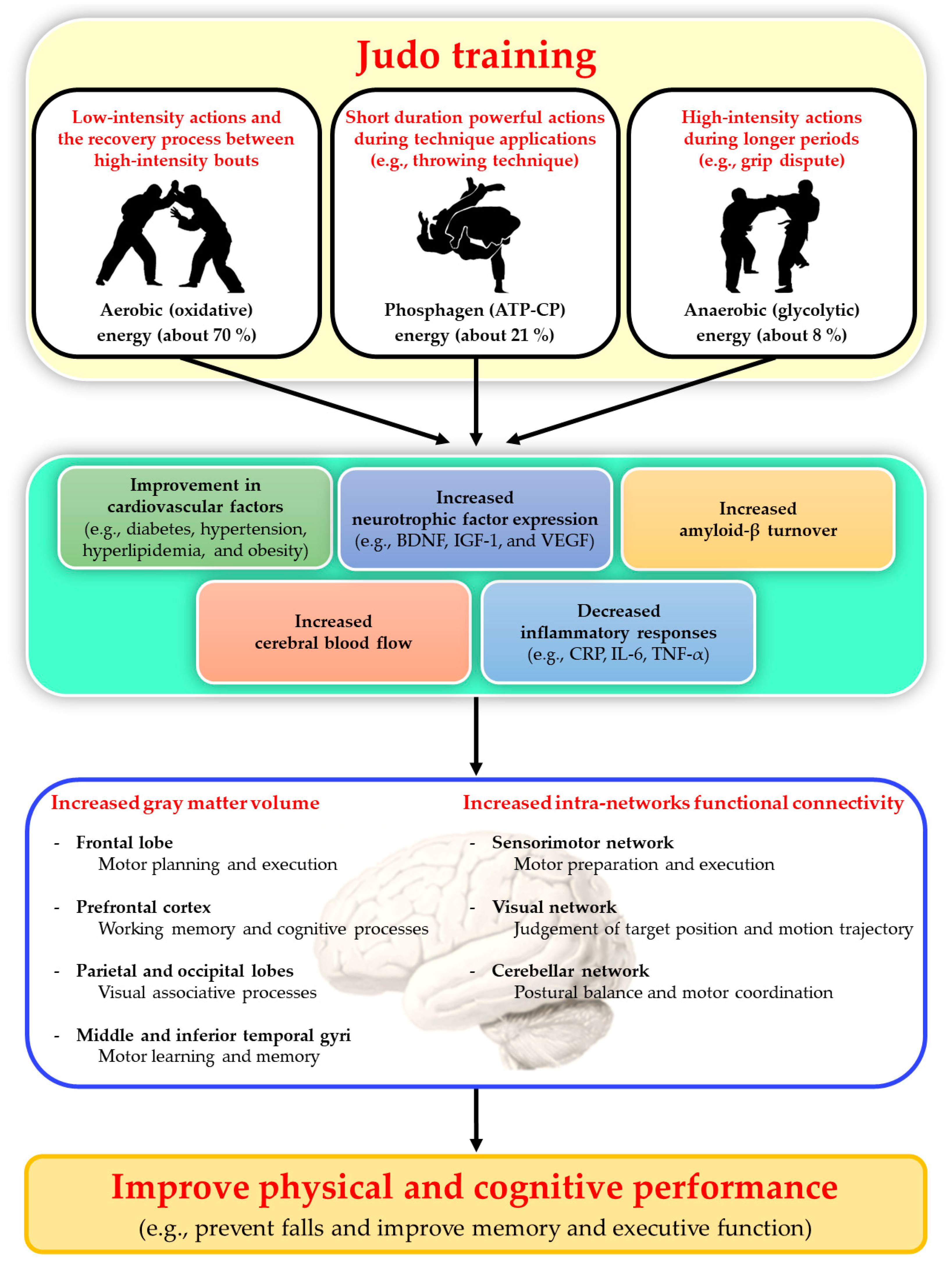

4. Possible mechanism of the brain effects of judo training in relation to improvement in physical and cognitive performance in the elderly

5. Conclusions and prospects

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ciaccioni, S.; Capranica, L.; Forte, R.; Chaabene, H.; Pesce, C.; Condello, G. Effects of a judo training on functional fitness, anthropometric, and psychological variables in old novice practitioners. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 27, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbeloto, F.; Miarka, B.; Guimarães, E.; Gomes, F.R.F.; Tagusari, F.I.; Tani, G. A new developmental approach for judo focusing on health, physical, motor, and educational attributes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Judo Federation. History. From Martial Art to Olympic Sport. Available online: https://www.ijf.org/history/from-martial-art-to-olympic-sport (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Ciaccioni, S.; Condello, G.; Guidotti, F.; Capranica, L. Effects of judo training on bones: a systematic literature review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 2882–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka, E.; Napierała, P.; Podfigurna, A.; Męczekalski, B.; Smolarczyk, R.; Grymowicz, M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas 2020, 139, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallaci, I.V.; Fabrício, D.M.; Alexandre, T.D.S.; Chagas, M.H.N. Association between falls and cognitive performance among community-dwelling older people: a cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2022, 140, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero-Odasso, M.; van der Velde, N.; Martin, F.C.; Petrovic, M.; Tan, M.P.; Ryg, J.; Aguilar-Navarro, S.; Alexander, N.B.; Becker, C.; Blain, H.; et al. World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age ageing 2022, 51, afac205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia; WHO guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, T. Preventive strategies for cognitive decline and dementia: benefits of aerobic physical activity, especially open-skill exercise. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, F.; Ciaccioni, S.; Guidotti, F.; Forte, R.; Sacripanti, A.; Capranica, L.; Tessitore, A. Risks and benefits of judo training for middle-aged and older people: a systematic review. Sports 2023, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaccioni, S.; Palumbo, F.; Forte, R.; Galea, E.; Kozsla, T.; Sacripanti, A.; Milne, A.; Lampe, N.; Lampe, Š.; Jelušić, T.; et al. Educating judo coaches for older practitioners. Art Sci. Judo 2022, 2, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Toronjo-Hornillo, L.; Castañeda-Vázquez, C.; Campos-Mesa, M.D.C.; González-Campos, G.; Corral-Pernía, J.; Chacón-Borrego, F.; DelCastillo-Andrés, Ó. Effects of the application of a program of adapted utilitarian judo (jua) on the fear of falling syndrome (fof) for the health sustainability of the elderly population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkkukangas, M.; Bååthe, K.S.; Hamilton, J.; Ekholm, A.; Tonkonogi, M. Feasibility of a novel Judo4Balance–fall preventive exercise programme targeting community-dwelling older adults. J. Frailty Sarcopenia Falls 2020, 5, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Mesa, M.C.; DelCastillo-Andrés, Ó.; Toronjo-Hornillo, L.; Castañeda-Vázquez, C. The effect of adapted utilitarian judo, as an educational innovation, on fear-of-falling syndrome. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaccioni, S.; Capranica, L.; Forte, R.; Pesce, C.; Condello, G. Effects of a 4-month judo program on gait performance in older adults. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2020, 60, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaccioni, S.; Pesce, C.; Capranica, L.; Condello, G. Effects of a judo training program on falling performance, fear of falling and exercise motivation in older novice judoka. Ido Mov. Culture. J. Martial Arts Anthrop. 2021, 21, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuyama, N.; Kamitani, T.; Ikumi, A.; Kida, M.; Kaneshiro, Y.; Akiyama, K. Assessment of the efficacy and safety of a judo exercise program in improving the quality of life among elderly patients. J. Rural Med. 2021, 16, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkkukangas, M.; Strömqvist Bååthe, K.; Ekholm, A.; Tonkonogi, M. High challenge exercise and learning safe landing strategies among community-dwelling older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadczak, A.D.; Verma, M.; Headland, M.; Tucker, G.; Visvanathan, R. A judo-based exercise program to reduce falls and frailty risk in community-dwelling older adults: a feasibility study. J. Frailty Aging 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odaka, M.; Kagaya, H.; Harada, T.; Futada, Y.; Yamaishi, A.; Sasaki, M. Effect of ukemi practice in judo on fear of falling and mobility skills in healthy older adults. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2023, 35, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujach, S.; Chroboczek, M.; Jaworska, J.; Sawicka, A.; Smaruj, M.; Winklewski, P.; Laskowski, R. Judo training program improves brain and muscle function and elevates the peripheral BDNF concentration among the elderly. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba-Pinheiro, C.J.; Figueiredo, N.M.A.; Carvalho, M.C.G.A.; Drigo, A.J.; Pernambuco, C.S.; Jesus, F.P.; Dantas, E.H.M. Adapted judo training on bone-variables in postmenopausal women in pharmacological treatment. Sport Sci. Health 2012, 8, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba-Pinheiro, C.J.; Carvalho, M.C.G.A.; Drigo, A.J.; Silva, N.S.L.; Pernambuco, C.S.; de Figueiredo, N.M.A.; Dantas, E.H.M. Combining adapted judo training and pharmacological treatment to improve bone mineral density on postmenopausal women: a two years study. Arch. Budo 2013, 9, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krampe, R.T.; Smolders, C.; Doumas, M. Leisure sports and postural control: can a black belt protect your balance from aging? Psychol. Aging 2014, 29, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muiños, M.; Ballesteros, S. Peripheral vision and perceptual asymmetries in young and older martial arts athletes and nonathletes. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2014, 76, 2465–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muiños, M.; Ballesteros, S. Sports can protect dynamic visual acuity from aging: a study with young and older judo and karate martial arts athletes. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2015, 77, 2061–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Cadenas, E.; Sretković, T.; Perales, J.C.; Petrović, J.; Sterkowicz-Przybycień, K.; Batez, M.; Drid, P. Mental toughness and perfectionism in judo: differences by achievement and age. The relation between constructs. Arch. Budo 2016, 12, 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Kodokan. History of Kodokan Judo. Available online: http://kodokanjudoinstitute.org/en/doctrine/history/ (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Kodokan. The Meanings of the Great Way “Judo”? Available online: http://kodokanjudoinstitute.org/en/doctrine/word/02/ (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Kodokan. What is “Seiryoku-Zenyo”? Available online: http://kodokanjudoinstitute.org/en/doctrine/word/seiryoku-zenyo/ (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Kodokan. What is “Jita-Kyoei”? Available online: http://kodokanjudoinstitute.org/en/doctrine/word/jita-kyoei/ (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- International Judo Federation. Judo Moral Code. Available online: https://www.ijf.org/moralcode (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Kodokan. Teachings of Kano Jigoro Shihan. Available online: http://kodokanjudoinstitute.org/en/doctrine/ (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Origua Rios, S.; Marks, J.; Estevan, I.; Barnett, L.M. Health benefits of hard martial arts in adults: a systematic review. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, D.H.; Stout, J.R.; Burris, P.M.; Fukuda, R.S. Judo for children and adolescents: benefits of combat Sports. Strength Cond. J. 2011, 33, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolska-Paczoska, B. The level of aerobic and anaerobic capacity and the results of a special mobility fitness test of female judo competitors aged 16–18 years. Balt. J. Health Phys. Act. 2010, 2, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, E.; Del Vecchio, F.B.; Matsushigue, K.A.; Artioli, G.G. Physiological profiles of elite judo athletes. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouergui, I.; Delleli, S.; Chtourou, H.; Formenti, D.; Bouhlel, E.; Ardigò, L.P.; Franchini, E. The role of competition area and training type on physiological responses and perceived exertion in female judo athletes. Int. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 19, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwagura, D.B.; Franchini, E. The grip dispute (kumi-kata) in judo: a scoping review. Rev. Artes Marciales Asiát. 2022, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodokan. Names of Judo Techniques. Available online: http://kodokanjudoinstitute.org/en/waza/list/ (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Dulgheru, M.V. Judo wrestler’s principles and social integration of the student practitioner. Marathon 2019, 11, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lampe, N.; Kajmović, H.; Šimenko, J.; Bečić, F. The effects of judo rule changes on contestant’s performance: Paris Grand Slam case study. Art Sci. Judo 2022, 2, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Franchini, E. High-intensity interval training in judo uchi-komi: fudamentals and practical recommendations. Art Sci. Judo 2021, 1, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Julio, U.F.; Panissa, V.L.G.; Esteves, J.V.; Cury, R.L.; Agostinho, M.F.; Franchini, E. Energy-system contributions to simulated judo matches. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchini, E.; Artioli, G.G.; Brito, C.J. Judo combat: time-motion analysis and physiology. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport. 2013, 13, 624–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, T. Benefits of table tennis for brain health maintenance and prevention of dementia. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1577–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, E.; Brito, C.J.; Fukuda, D.H.; Artioli, G.G. The physiology of judo-specific training modalities. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 1474–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodokan. Kata. Available online: http://kodokanjudoinstitute.org/en/waza/forms/ (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Palumbo, F.; Ciaccioni, S.; Guidotti, F.; Forte, R.; Sacripanti, A.; Capranica, L.; Tessitore, A. Risks and benefits of judo training for middle-aged and older people: a systematic review. Sports 2023, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, U.; Ayliffe, L.; Visvanathan, R.; Headland, M.; Verma, M.; Jadczak, A.D. Judo-based exercise programs to improve health outcomes in middle-aged and older adults with no judo experience: A scoping review. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2023, 23, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faro, H.K.C.; Machado, D.G.D.S.; Bortolotti, H.; do Nascimento, P.H.D.; Moioli, R.C.; Elsangedy, H.M.; Fontes, E.B. Influence of judo experience on neuroelectric activity during a selective attention task. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Kong, X.; Zhanng, Y.; Luo, Y.; Ma, J. Effects of combat sports on functional network connectivity in adolescents. Neuroradiology 2021, 63, 1863–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacini, W.F.; Cannonieri, G.C.; Fernandes, P.T.; Bonilha, L.; Cendes, F.; Li, L.M. Can exercise shape your brain? Cortical differences associated with judo practice. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2009, 12, 688–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schor, B.; Silva, S.G.D.; Almeida, A.A.; Pereira, C.A.B.; Arida, R.M. Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor is higher after combat training (Randori) than incremental ramp test in elite judo athletes. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2019, 52, e8154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| References |

Overview of studies (1. Study Design; 2. Participants; 3. Characteristics of judo training; 4. Outcome measures; 5. Main findings) |

| Toronjo-Hornillo et al. [13] |

|

| Ciaccioni et al. [1] |

|

| Arkkukangas et al. [14] |

|

| Campos-Mesa et al. [15] |

|

| Ciaccioni et al. [16] |

|

| Ciaccioni et al. [17] |

|

| Sakuyama et al. [18] |

|

| Arkkukangas et al. [19] |

|

| Jadczak et al. [20] |

|

| Odaka et al. [21] |

|

| Kujach et al. [22] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).