Submitted:

28 June 2023

Posted:

28 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Adaptation mechanisms of plants to drought

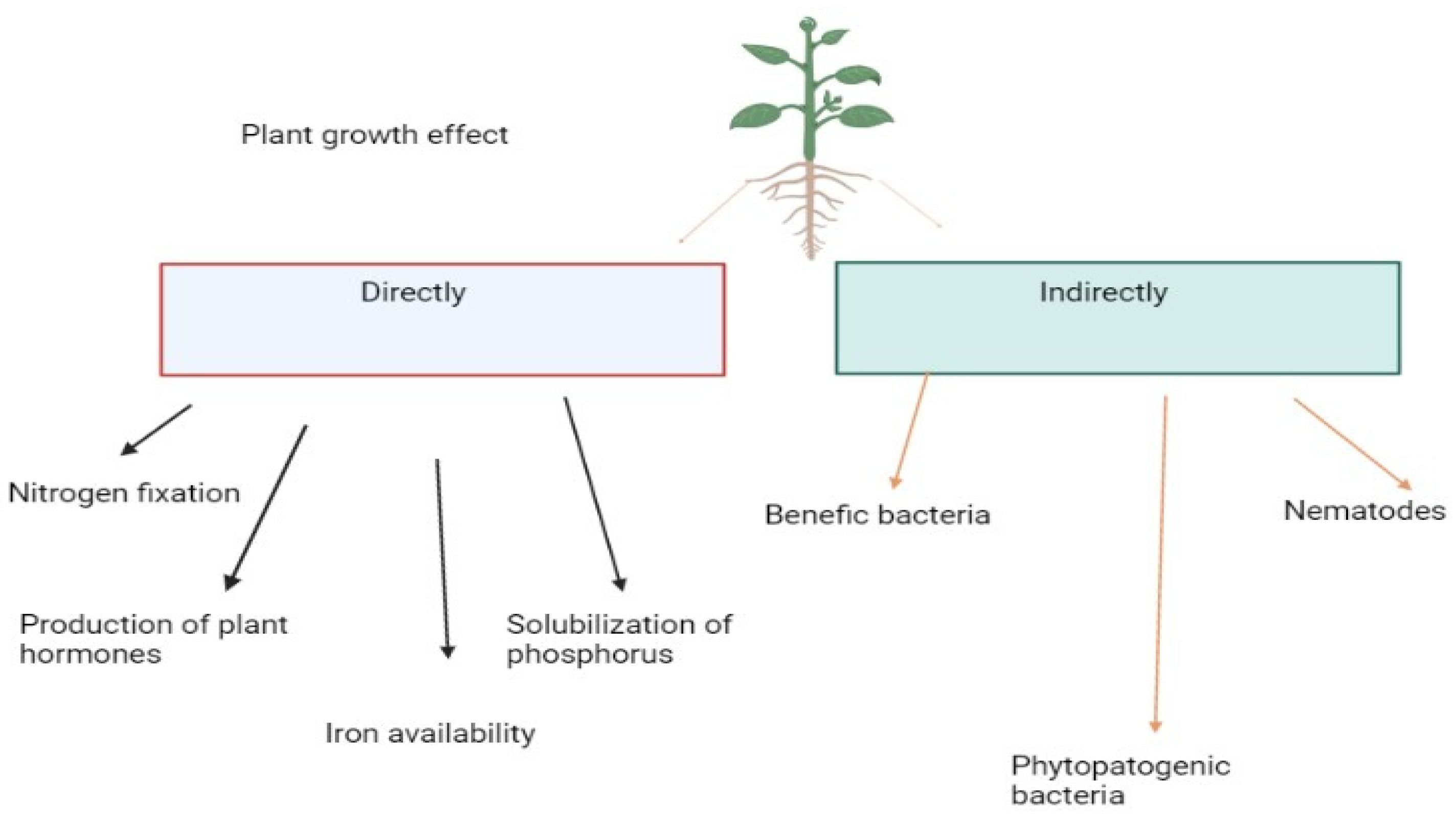

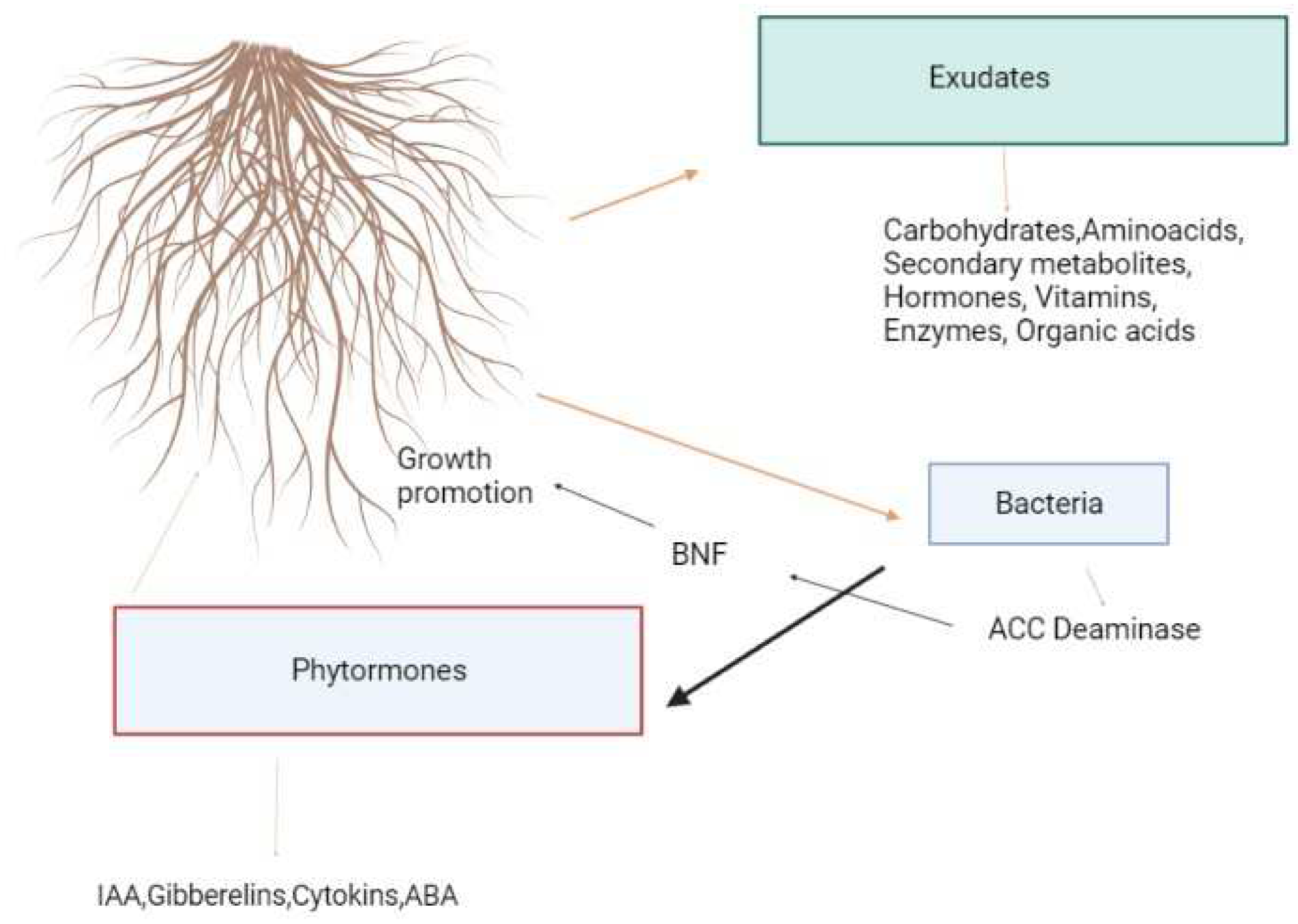

3. Growth-Promoting Bacteria in Plants

4. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria (PGPB) and stress tolerance

4.1. Plant morpho-physiological traits are modulated by bacterial phytohormones

4.2. Biosynthetic Bacteria and Induced Accumulation in Plants

4.3. A self-protective and water-retaining property of bacterial exopolysaccharides

4.4. The role of volatile organic compounds in drought bioprotection by bacteria

4.5. Mechanisms of bacterial protection and repair in drought-stressed plant tissue

5. Drought Stress Mitigation Using Microbial Inoculants in Agroecosystems

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malhi, G.S.; Kaur, M.; Kaushik, P. Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture and Its Mitigation Strategies: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.A.; Ramankutty, N.; Brauman, K.A.; Cassidy, E.S.; Gerber, J.S.; Johnston, M.; Mueller, N.D.; O’Connell, C.; Ray, D.K.; West, P.C.; et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 2011, 478, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, S.; Khalil, S.; Ayub, N.; Rashid, M. In vitro solubilization of inorganic phosphate by phosphate solubilizing microorganism (PSM) from maize rhizosphere. Intl. J. Agric. Biol. 2002, 4, 454–458. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, M. Inducing drought tolerance in plants: Recent advances. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.S.; Siddiqui, Z.A. Effect of phosphate solubilizing microorganisms and Rizobium sp. on the growth, nodulation, yield and root-rot disease complex of chickpea under field condition. Afr. J. Biotech. 2009, 8, 3489–3496. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, D.E.; Chaitanya, K.V. Photosynthesis and antioxidative defense mechanisms in deciphering drought stress tolerance of crop plants. Biol. Plant. 2016, 60, 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, G. Plant-microbe interactions promoting plant growth and health: perspectives for controlled use of microorganisms in agriculture. Appl. Microbiol Biotech. 2009, 84, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broeckling, C.D. 2008. Root exudates regulate soil fungal community composition and diversity. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 2008, 74, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Reynolds, M.P.; Wang, J.; Chang, X.; Mao, X.; Jing, R. Recognizing the hidden half in wheat: Root system attributes associated with drought tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 5117–5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deubel, A.; Gransee, G.; Merbach, W. Transformation of organic rhizodeposits by rhizoplane bacteria and its influence on the availability of tertiary calcium phosphate. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2000, 163, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Mahmood, A.; Maqbool, R.; Albaqami, M.; Sher, A.; Sattar, A.; Khosa, G.B.; Nawaz, M.; Hassan, M.U.; Al-Yahyai, R. Key insights to develop drought-resilient soybean: A review. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2022, 34, 102089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, M.; Hafeez, F.E.; Saleem, M.; Malik, K.A. Phosphorus uptake and growth promotion of chickpea by co-inoculation of mineral phosphate solubilizing bacteria and a mixed rhizobial culture. Aust J. Exp Agric. 2004, 44, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, M.; Mendes, R.; Costa, L.A.S.; Bueno, C.G.; Meng, Y.; Folimonova, S.Y.; Garrett, K.A.; Martins, S.J. The role of plant- associated bacteria, fungi, and viruses in drought stress mitigation. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duponnois, R.; Kisa, M.; Plenchette, C. Phosphate solubilizing potential of the nemato fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2006, 169, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, V.M.; Evans, C.S. Oxalate production by fungi: its role in pathogenicity and ecology in the soil environment. Can J. Microbiol. 1996, 42, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochard, H.; Coll, L.; Le Roux, X.; Améglio, T. Unraveling the effects of plant hydraulics on stomatal closure during water stress in walnut. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, U.; Windt, C.W.; Ponomarenko, A.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Gersony, J.; Rockwell, F.E.; Holbrook, N.M. Stomatal closure, basal leaf embolism, and shedding protect the hydraulic integrity of grape stems. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, A.; Heidari, G.; Sohrabi, Y.; Badakhshan, H.; Mohammadi, K. 2011. Influence of bio, organic and chemical fertilizers on medicinal pumpkin traits. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 5590–5597. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S.; Wang, X.; Mubeen, I.; Kamran, M.; Kanwal, I.; Díaz, G.A.; Abbas, A.; Parveen, A.; Atiq, M.N.; Alshaya, H.; et al. Phytohormones Trigger Drought Tolerance in Crop Plants: Outlook and Future Perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandurska, H. Drought Stress Responses: Coping Strategy and Resistance. Plants 2022, 11, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henri, F.; Laurette, N.N.; Annette, A.; John, Q.; Wolfgang, M.; François-Xavier, E.; Dieudonné, E. Solubilization of inorganic phosphates and plant growth promotion by strains of Pseudomonas fluorescens isolated from acidic soils of Cameroon. Afri J. Microbiol Res. 2008, 2, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Hilda, R.; Fraga, R. Phosphate solubilizing bacteria and their role in plant growth promotion. Biotech Adv. 2000, 17, 319–359. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, N.C. Turgor maintenance by osmotic adjustment, an adaptive mechanism for coping with plant water deficits. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greacen, E.L.; Oh, J.S. Physics of Root Growth. Nat. New Biol. 1972, 235, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constable, G.A.; Hearn, A.B. Agronomic and physiological responses of soybean and sorghum crops to water deficits I. Growth, development and yield. Funct. Plant Biol. 1978, 5, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinsinger, P. Bioavailability of soil inorganic P in the rhizosphere as affected by root induced chemical changes: a review. Plant Soil. 2001, 237, 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igual, J.M.; Valverde, A.; Cervantes, E.; Velázquez, E. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria asinoculants for agriculture: use of updated molecular techniques in their study. Agronomie. 2001, 21, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wani, A.S.; Pichtel, J.; Ahmad, A. Role of proline under changing environments: A review. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Jiang, J.-G. Osmotic adjustment and plant adaptation to environmental changes related to drought and salinity. Environ. Rev. 2010, 18, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathiresan, G.; Manickam, G.; Parameswaran, P. 1995. Efficiency of phosphobacteria addition on cane yield and quality. Cooperative Sugar. 1995, 26, 629–631. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, H.-A.A.; Mekki, B.B.; Abd El-Sadek, M.E.; El Lateef, E.E. Effect of L-Ornithine application on improving drought tolerance in sugar beet plants. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, B.; Yang, L.; Cong, W.; Zu, Y.; Tang, Z. The improved resistance to high salinity induced by trehalose is associated with ionic regulation and osmotic adjustment in Catharanthus roseus. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 77, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.M.; Nahar, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M. Trehalose-induced drought stress tolerance: A comparative study among different Brassica species. Plant Omics 2014, 7, 271–283. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, N.A.; Waseem, M.; Ameen, R.; Ashraf, M. Trehalose pretreatment induces drought tolerance in radish (Raphanus sativus L.) plants: Some key physio-biochemical traits. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 38, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Zaidi, A.; Wani, P.A. Role of phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms in sustainable agriculture - A review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2007, 27, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Jordan, D.; Mc Donald, G.A. Effect of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae on tomato growth and soil microbial activity. Biol. Fertil Soils. 1998, 26, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohbat, Z.I. Non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence and its components–recent advances. J. Life Sci. Biomed. 2022, 4, 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, I.; Cela, J.; Alegre, L.; Munné-Bosch, S. Antioxidant Defenses Against Drought Stress. In Plant Responses to Drought Stress: From Morphological to Molecular Features; Aroca, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 231–258. [Google Scholar]

- Pyngrope, S.; Bhoomika, K.; Dubey, R.S. Oxidative stress, protein carbonylation, proteolysis and antioxidative defense system as a model for depicting water deficit tolerance in Indica rice seedlings. Plant Growth Regul. 2013, 69, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheoran, S.; Thakur, V.; Narwal, S.; Turan, R.; Mamrutha, H.M.; Singh, V.; Tiwari, V.; Sharma, I. Differential activity and expression profile of antioxidant enzymes and physiological changes in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under drought. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 177, 1282–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, A.; Awad, D.; Samarah, N. Gene expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes in barley (Hordeum vulgare L. ) under controlled severe drought. J. Plant Interact. 2015, 10, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kpomblekou, K.; Tabatabai, M.A. Effect of organic acids on release of phosphorus from phosphate rocks. Soil Sci. 1994, 158, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.E.; Pankhurst, C.E. Soil organisms and sustainable productivity. Australian J. Soil Res. 1992, 30, 855–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahas, E. Factors determining rock phosphate solubilization by microorganism isolated from soil. World J. Microb Biotech. 1996, 12, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nihorimbere, V.; Ongena, M.; Smargiassi, M.; Thonart, P. Beneficial effect of the rhizosphere microbial community for plant growth and health. Biotechnol Agron Soc Environ. 2011, 15, 327–337. [Google Scholar]

- Fierer, N.; Jackson, R.B. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponmurugan, P.; Gopi, G. Distribution pattern and screening of phosphate solubilizing bacteria isolated from different food and forage crops. J. Agron. 2006, 5, 600–604. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrguez, H.; Fraga, R. Phosphate solubilizing bacteria and their role in plant growth promotion. Biotech Adv. 1999, 17, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhzadi, A.; Asgharzadeh, A.; Darvish, F.; Nourmohammadi, G.; Majidi, E. Influence of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on dry matter accumulation and yield of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L. ) under field condition. Am-Euras. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2008, 3, 253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Jjemba, P.K.; Alexander, M. Possible determinants of rhizosphere competence of bacteria. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1999, 31, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhzadi, A.; Toashih, V. Nutrient uptake and yield of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) inoculated with plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Aust J. Crop Sci. 2011, 5, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas, S.B. , Andre´ s J.A., Rovera M. and Correa N.S. Phosphate-solubilizing Pseudomonas putida can influence the rhizobia-legume symbiosis. Soil BiolBiochem. 2006, 38, 3502–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, F.L.; Busato, J.G.; de Paula, A.M.; da Silva Lima, L.; Aguiar, N.O.; Canellas, L.P. Plant growth promoting bacteria and humic substances: Crop promotion and mechanisms of action. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Verma, J.P. Does plant—Microbe interaction confer stress tolerance in plants: A review? Microbiol. Res. 2018, 207, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etesami, H.; Maheshwari, D.K. Use of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPRs) with multiple plant growth promoting traits in stress agriculture: Action mechanisms and future prospects. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 156, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saikia, S.P.; Jain, V. Biological nitrogen fixation with non- legumes:an achievable able target or a dogma. Curr. Sci. 2007, 92, 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Schroth, M.N.; Hancock, J.G. Selected topics in biological control. Ann Rev Microbiol. 1981, 35, 453––476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, P.M.; Veeraputhran, R. Effect of organic manure, biofertilizers, inorganic nitrogen and zinc on growth and yield of rabi rice. Madras Agric J. 2000, 2, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Shehata, M.M.; El-khawas, S.A. Effect of biofertilizers on growth parameters, yield characters, nitrogenous components, nucleic acids content, minerals, oil content, protein profiles and DNA banding pattern of sunflower (Helianthus annus L. cv. Vedock) yield. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2003, 6, 1257–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzanesh, M.H.; Alikhani, H.A.; Khavazi, K.; Rahimian, H.A.; Miransari, M. Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) growth enhancement by Azospirillum sp. under drought stress. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Galván, A.E.; Cortés-Patiño, S.; Romero-Perdomo, F.; Uribe-Vélez, D.; Bashan, Y.; Bonilla, R.R. Proline accumulation and glutathione reductase activity induced by drought-tolerant rhizobacteria as potential mechanisms to alleviate drought stress in Guinea grass. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 147, 103367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Sadeghi, A.; Safaie, N. Streptomyces alleviate drought stress in tomato plants and modulate the expression of transcription factors ERF1 and WRKY70 genes. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 265, 109206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, H.; Bano, A.; Wilson, N.L.; Nosheen, A.; Naz, R.; Hassan, M.N.; Ilyas, N.; Saleem, M.H.; Noureldeen, A.; Ahmad, P. Drought-tolerant Pseudomonas sp. showed differential expression of stress-responsive genes and induced drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, B.; Shahid, M.; Syed, A.; Rajput, V.D.; Elgorban, A.M.; Minkina, T.; Bahkali, A.H.; Lee, J. Drought tolerant Enterobactersp./Leclercia adecarboxylata secretes indole-3-acetic acid and other biomolecules and enhances the biological attributes of Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek in water deficit conditions. Biology 2021, 10, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasim, W.A.; Osman, M.E.H.; Omar, M.N.; Salama, S. Enhancement of drought tolerance in Triticum aestivum L. seedlings using Azospirillum brasilense NO40 and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia B11. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021, 45, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundara, B.; Natarajan, V.; Hari, K. Influence of phosphorus solubilizing bacteria on the changes in soil available phosphorus and sugarcane yields. Field Crops Res. 2002, 77, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SundraRao, W.V.B; Sinha, M.K. Phosphate dissolving organisms in soil and rhizosphere. Indian J. Agric Sci. 1963, 33, 272–278. [Google Scholar]

- Tambekar, D.H.; Gulhane, S.R.; Somkuwar, D.O.; Ingle, K.B.; Kanchalwar, S.P. Potential Rhizobium and phosphate solubilizers as a biofertilizers from saline belt of Akola and Buldhana district, India. Res. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2009, 5, 578–582. [Google Scholar]

- Pantoja-Guerra, M.; Valero-Valero, N.; Ramírez, C.A. Total auxin level in the soil–plant system as a modulating factor for the effectiveness of PGPR inocula: A review. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroy, V.; Cassán, F.; Masciarelli, O.; Del Papa, M.F.; Lagares, A.; Luna, V. Isolation and characterization of endophytic plant growth-promoting (PGPB) or stress homeostasis-regulating (PSHB) bacteria associated to the halophyte Prosopis strombulifera. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 85, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.; Tian, S.; Cai, M.; Xie, G. Phosphate solubilizing and mineralizing abilities of bacteria isolated from soils. Pedosphere. 2008, 18, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, P.; Holguin, G.; Puente, M.; Cortes, AE.; Bashan, Y. Phosphate solubilizing microorganisms associated with the rhizosphere of mangroves in a semi arid coastal lagoon. Biol Fertil Soils. 2000, 30, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente Lima, J.; Tinôco, R.S.; Olivares, F.L.; Moraes, A.J.G.d.; Chia, G.S.; Silva, G.B.d. Hormonal imbalance triggered by rhizobacteria enhance nutrient use efficiency and biomass in oil palm. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 264, 109161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Hasnain, S. Auxin-producing Bacillus sp. : Auxin quantification and effect on the growth of Solanum tuberosum. Pure Appl. Chem. 2010, 82, 313–319. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi Alagoz, S.; Zahra, N.; Hajiaghaei Kamrani, M.; Asgari Lajayer, B.; Nobaharan, K.; Astatkie, T.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Farooq, M. Role of Root Hydraulics in Plant Drought Tolerance. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelaw, M.A. Growth promotion of plants inoculated with phosphate solubilizing fungi. Adv Agron. 2000, 69, 99–151. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, C.Q.; Chi, R.A.; Huang, X.H.; Zhang, W.X. Optimization for rock phosphate solubilization by phosphate-solubilizing fungi isolated from phosphate mines. Ecol. Eng. 2008, 33, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.C.; Bottini, R.; Piccoli, P.N. Azospirillum brasilense Sp 245 produces ABA in chemically-defined culture medium and increases ABA content in arabidopsis plants. Plant Growth Regulation 2008, 54, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, M.; Campo, R.J.; Souza, E.M.; Pedrosa, F.O. Inoculation with selected strains of Azospirillum brasilense and A. lipoferum improves yields of maize and wheat in Brazil. Plant Soil 2010, 331, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, M.V.; Bottini, R.; de Souza Filho, G.A.; Cohen, A.C.; Moreno, D.; Gil, M.; Piccoli, P. Bacteria isolated from roots and rhizosphere of Vitis vinifera retard water losses, induce abscisic acid accumulation and synthesis of defense-related terpenes in in vitro cultured grapevine. Physiol. Plant. 2014, 151, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, A.; Azawi, S.K.A. Occurrence of phosphate solubilizing bacteria in some Iranian soils. Plant Soil. 1998, 117, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaddy, E.; Perevolosky, A. Enhancement of growth and establishment of oak seedling by inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense. Forest Eco Manage. 1995, 72, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaddy, E.; Perevolosky, A.; Okon, Y. Promotion of plant growth by inoculation with aggregated and single cell suspension by Azospirillum brasilense. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1993, 25, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.I.; Rashid, A.; Faisul-ur-Rasool; Mahdi, S.S.; Haq, S.A.; Raies, A.B. Effect of Rhizobium and Vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizae fungi on green Gram (Vigna radiata L.Wilczek) under temperate conditions. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2010, 1, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Bisleski, R.L. Phosphate transport and phosphate availability, Ann. Rev.Pl.Physiol. 1973, 24, 225–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundrett, M.C.; Abbott, L.K. Mycorrhizal fungus propagules in the jarrh forest. I. Spatial variability in inoculam levels. New Phytol. 1995, 131, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champawat, R.S. ; Pathak,V. N. Effect of Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on growth and nutrition uptake of pearl millet, Indian J.Mycol.Pl.Pathol. 1993, 23, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Naveed, M.; Mitter, B.; Reichenauer, T.G.; Wieczorek, K.; Sessitsch, A. Increased drought stress resilience of maize through endophytic colonization by Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN and Enterobacter sp. FD17. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 97, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, N.O.; Medici, L.O.; Olivares, F.L.; Dobbss, L.B.; Torres-Netto, A.; Silva, S.F.; Novotny, E.H.; Canellas, L.P. Metabolic profile and antioxidant responses during drought stress recovery in sugarcane treated with humic acids and endophytic diazotrophic bacteria. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2016, 168, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honma, M.; Shimomura, T. Metabolism of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1978, 42, 1825–1831. [Google Scholar]

- Glick, B.R.; Penrose, D.M.; Li, J. A model for the lowering of plant ethylene concentrations by plant growth-promoting bacteria. J. Theor. Biol. 1998, 190, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchense, L.C.; Peterson, R.L.; Ellis, B.E. The future of ectomycorrhizal fungi as biological control agents. Phytoprotection 1989, 70, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, G.E.; Guillaume, P.; Tahiri, A.A.; Gianinazzi-Pearson, V.; Gianinazzi, S. Changes in polypeptide patterns in tobacco roots by Glomus species. Mycorrhiza 1994, 4, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Sziderics, A.H.; Rasche, F.; Trognitz, F.; Sessitsch, A.; Wilhelm, E. Bacterial endophytes contribute to abiotic stress adaptation in pepper plants (Capsicum annuum L. ). Can. J. Microbiol. 2007, 53, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardharajula, S.; Zulfikar Ali, S.; Grover, M.; Reddy, G.; Bandi, V. Drought-tolerant plant growth promoting Bacillus spp.: Effect on growth, osmolytes, and antioxidant status of maize under drought stress. J. Plant Interact. 2011, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Gupta, A.; Mohapatra, S. A comparative analysis of exopolysaccharide and phytohormone secretions by four drought- tolerant rhizobacterial strains and their impact on osmotic-stress mitigation in Arabidopsis thaliana. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fa Yuan, W.; Zhao Yong, S. Biodiversity of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in China: a Review. Advances in Environmental Biology 2008, 2, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ojuederie, O.B.; Olanrewaju, O.S.; Babalola, O.O. Plant growth promoting rhizobacterial mitigation of drought stress in crop plants: Implications for sustainable agriculture. Agronomy 2019, 9, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Bano, A. Exopolysaccharide producing rhizobacteria and their impact on growth and drought tolerance of wheat grown under rainfed conditions. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.M.; Reader, R.J. Host plant benefit from association with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: variation due to differences in size of mycelium, Biol. Ferti.Soils 2002, 36, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilli, F.; Loreto, F.; Baccelli, I. Exploiting plant volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in agriculture to improve sustainable defense strategies and productivity of crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, C.-M.; Farag, M.A.; Hu, C.-H.; Reddy, M.S.; Wei, H.-X.; Paré, P.W.; Kloepper, J.W. Bacterial volatiles promote growth in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4927–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blom, D.; Fabbri, C.; Connor, E.C.; Schiestl, F.P.; Klauser, D.R.; Boller, T.; Eberl, L.; Weisskopf, L. Production of plant growth modulating volatiles is widespread among rhizosphere bacteria and strongly depends on culture conditions. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 3047–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subrahmanyam, G.; Kumar, A.; Sandilya, S.P.; Chutia, M.; Yadav, A.N. Diversity, plant growth promoting attributes, and agricultural applications of rhizospheric microbes. Plant Microbiomes Sustain. Agric. 2020, 25, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries, A. Use of mycorrhiza in agriculture. Cri. Rev. Biotech. 1987, 5, 319–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.A.; Ayub, N.; Mirza, S.N.; Nizami, S.M.; Azam, M. Synergistic effect of dual inoculation (Vesicualr- arbuscular mycorrhizae) on the growth and nutrients uptake of Medicago sativa, Pak. J.Bot. 2008, 40, 939–945. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.M.; Kang, B.R.; Han, S.H.; Anderson, A.J.; Park, J.-Y.; Lee, Y.-H.; Cho, B.H.; Yang, K.-Y.; Ryu, C.-M.; Kim, Y.C. 2R, 3R-butanediol, a bacterial volatile produced by Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6, is involved in induction of systemic tolerance to drought in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2008, 21, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, B.; Wang, X.; Saleem, M.H.; Sumaira; Hafeez, A.; Afridi, M.S.; Khan, S.; Zaib Un, N.; Ullah, I.; Amaral Júnior, A.T.D.; et al. PGPR-Mediated Salt Tolerance in Maize by Modulating Plant Physiology, Antioxidant Defense, Compatible Solutes Accumulation and Bio-Surfactant Producing Genes. Plants 2022, 11, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivetha, N.; Lavanya, A.K.; Vikram, K.V.; Asha, A.D.; Sruthi, K.S.; Bandeppa, S.; Annapurna, K.; Paul, S. PGPR-Mediated Regulation of Antioxidants: Prospects for Abiotic Stress Management in Plants. In Antioxidants in Plant-Microbe Interaction; Singh, H.B., Vaishnav, A., Sayyed, R.Z., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 471–497. [Google Scholar]

- El-Komy, M.; Hesham, A. Coimmobilization of Azospirillum lipoferum and Bacillus megaterium for successful phosphorus and nitrogen nutrition of wheat plants. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2004, 43, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- El-Komy, H.M.; Hamdia, M.A.; El-Baki, G.K.A. 2003. Nitrate reductase in wheat plants grown under water stress and inoculated with Azospirillum spp. Biol. Plant. 2003, 46, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lang, D.; Zhang, X. Growth-promoting bacteria alleviates drought stress of G. uralensis through improving photosynthesis characteristics and water status. J. Plant Interact. 2019, 14, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulchieri, M.; Frioni, L. Azospirillum inoculation on maize (Zea mays): Effect of yield in a field experiment in Central Argentina. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1994, 26, 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.L.; Medhane, N.S. Seed inoculation studies in gram (Cicer arietinum L.) with different strains of Rhizobium sp. Plant Soil 1974, 40, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.L.; Halo, B.A.; Elyassi, A.; Ali, S.; Al-Hosni, K.; Hussain, J.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Lee, I.-J. Indole acetic acid and ACC deaminase from endophytic bacteria improves the growth of Solanum lycopersicum. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 21, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc A Fee, B.J.; Fortin, J.A. Comparative effects of the soil microflora on ectomycorrhizal inoculation of conifer seedling. New Phytol. 1986, 108, 108–443. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza, R.; Schoenfeld, R.; Passaglia, L.M.P. Bacterial inoculants for rice: Effects on nutrient uptake and growth promotion. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2016, 62, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldotto, L.E.B.; Baldotto, M.A.; Canellas, L.P.; Bressan-Smith, R.; Olivares, F.L. Growth promotion of pineapple’Vitória’by humic acids and Burkholderia spp. during acclimatization. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo 2010, 34, 1593–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Bhatnagar, A.; Kalla, A.; Narula, N. In vitro nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, survival and nutrient release by Azotobacter strains in an aquatic system. Biores. Technol. 2001, 80, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geurts, R.; Bisseling, T. Rhizobium nod factor perception and signalling. Plant Cell 2002, 14, S239–S249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosro, M.; Yousef, S. Bacterial biofertilizers for sustainable crop production: A review. ARPN J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2012, 7, 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Kavamura, V.N.; Santos, S.N.; Silva, J.L.D.; Parma, M.M.; Ávila, L.A.; Visconti, A.; Zucchi, T.D.; Taketani, R.G.; Andreote, F.D.; Melo, I.S.d. Screening of Brazilian cacti rhizobacteria for plant growth promotion under drought. Microbiol. Res. 2013, 168, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-M.; Shahzad, R.; Bilal, S.; Khan, A.L.; Park, Y.-G.; Lee, K.-E.; Asaf, S.; Khan, M.A.; Lee, I.-J. Indole-3-acetic-acid and ACC deaminase producing Leclercia adecarboxylata MO1 improves Solanum lycopersicum L. growth and salinity stress tolerance by endogenous secondary metabolites regulation. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanasamy, S.; Thankappan, S.; Kumaravel, S.; Ragupathi, S.; Uthandi, S. Complete genome sequence analysis of a plant growth-promoting phylloplane Bacillus altitudinis FD48 offers mechanistic insights into priming drought stress tolerance in rice. Genomics 2023, 115, 110550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, T.P.; Strohfus, B. Short Communication: Effect of carbon source on exopolysaccharide production by Sphingomonas paucimobilis ATCC 31461. Microbiol. Res. 1999, 153, 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microorganisms | Plant | Method of action | Cit. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azospirillum sp. | Wheat | Auxin and N concentrations are highest | [60] |

| Bacillus sp. | Grass | Antioxidant system response and early proline accumulation | [61] |

| Streptomyces sp. | Tomato | Increasing the content of different sugars | [62] |

| Pseudomonas sp. | Arabidopsis | Exopolysaccharide, gibberellic acid, abscisic acid, and indole acetic acid deaminase activity are higher | [63] |

| Enterobacter sp. | Bean | Increase the levels of proline, malondialdehyde, and antioxidant enzymes | [64] |

| Azospirillum brasilense | Wheat | A decrease in H2O2 accumulation and a decrease in the production of proline and catalase as well as peroxidase activity | [65] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).