1. Introduction

The use of assistance dogs can have a profound positive impact on the lives of their owners, with considerable focus in the recent research body. This impact is especially crucial for older adults who are also more likely to experience health declines, such as in vision and hearing, which warrant the use of an assistance dog. Further, it is important to note the benefits extend far beyond mere practical tasks, but also across mental, physical, and social health domains [

1]. As such, it seems rational that older adults should be encouraged to acquire an assistance dog as a multi-faceted treatment and support. However, a number of actual and perceived barriers prevent or deter this age group from this acquisition, in particular the availability of suitable accommodation.

Current legislation, at state and federal levels, including the Guide, Hearing and Assistance Dogs Act 2009 [

2] and Disability Discrimination Act 1992 [

3], is designed to protect the rights of owners and their assistance dogs. This includes maintaining their right to sufficient accommodation, outlawing discrimination based on refusal as well as any condition that would lead to their separation. Despite this, it has been suggested that many aged care facilities in Australia continue to refuse to allow owners to relocate to the facility with their assistance dog, with one report finding as little as 18% allowing residents to keep an animal of any kind [

4,

5]. This is a considerable barrier not only in discouraging initial acquisition, but in their retention. The latter potentially contributes to significant distress for both owner and dog, with the loss or separation from an assistance dog creating distress greater than that of a companion dog [

6].

Given this is an issue with the potential to affect a number of key stakeholders, it is important to consider the above through the lens of a wide range of people who are either directly or indirectly impacted, such as allied health staff, animal professionals, aged care staff, and assistance dog owners themselves. These individuals are likely to have competing interests and differing opinions, all of which should be harnessed for well-rounded discussion and solutions. Deliberative democracy involves providing participants with adequate information, before facilitating discussion that not only takes into consideration differing views but works to integrate the views of all participants based on a culmination of all participants’ perspectives [

7]. This methodology has received support for use within the public policy sphere, with the opportunity to raise and consider alternative perspectives increasing the likelihood of policy acceptability and thus increased likelihood of successful implementation [

8]. While traditionally these discussions would be held in person, the boom of online meeting software has allowed for the adaptation of online deliberative democracy. While this comes with possible technical difficulties, it has been found to lead to the same outcomes [

9], with the benefits of improved scheduling and recording capabilities, and the ability to complete follow-ups with participants via email. This allows for increased capabilities to reach consensus on key issues.

The current study thus aims to use deliberative democracy to explore whether older adults with assistance dogs should be allowed to retain their dog when they relocate to an aged care facility, and what factors should impact this decision (e.g., dog size, care abilities). Further, if they were allowed to retain their dog, what would be the best practice to allow for an effective transition and continued support within the aged care facility.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants (N=18) were recruited via a convenient sample of existing professional networks. The authors selected professionals and consumers with a range of backgrounds and experiences, all of whom had relevant experience or involvement with older adults, aged care, or assistance animals (See ‘

Table 1’). Potential participants were initially invited by direct email, and those who indicated interest were then sent participant information, consent form, and instructions to nominate their available dates and times via an online poll. The study was approved by the Research Ethics and Integrity Board at the University of Queensland (2022/HE001752), and informed consent was received from all participants prior to the commencement of the study.

2.2. Design

The current study used an adapted an exploratory deliberative democracy methodology with qualitative and quantitative findings. Qualitative data was collected during focus groups, which was summarized into key common points. Where deliberation of key points was not reached, or response priority was unclear, the points were developed into a questionnaire format for ranking, providing subsequent quantitative data.

2.3. Procedure

On receipt of consent forms and time availability from all participants, 3 focus online groups were held, with numbers kept as even as possible to allow for minimal group sizes to promote discussion and engagement from all participants (Group 1, n=6; Group 2, n=6; Group 3, n=5). While ideally this allocation would consider the spread by participant experience, availability needed to take precedence due to participant availability.

All focus groups followed an identical format, facilitated by PowerPoint slides containing all crucial information. Firstly, participants introduced themselves and their relevant background. Secondly, they were presented with background information on the issue (See ‘

Appendix A’) to ensure all had a base-level understanding of the issue. Thirdly, participants were provided with a list of key assumptions for the subsequent case studies, to ensure the brevity and specificity of discussion across all groups. These included having them assume that in both case studies the assistance dog owner was:

Healthy enough to care for their dog themselves

Does not have cognitive functioning impairments

Intends to relocate from their home to an aged care facility

Previously lived alone

Fourthly, they were presented with 2 differing case studies and a list of questions. This not only guided the conversation and ensured relevant discussion, but also gave tangible examples for how the cases may or may not differ within their considerations. These included:

Case 1: Person A has a severe hearing impairment, for which she has a hearing dog to assist in alerting her to key sounds (e.g., the doorbell, kettle, and smoke alarm). She has owned her hearing dog for 5 years, which is a small terrier.

Case 2: Person B is blind, for which he has a guide dog to assist in his mobility. He previously used a cane but did not find this to be as effective. He has owned his guide dog for 5 years, which is a large Labrador.

Questions:

What would an appropriate assistance dog policy for the aged care home look like?

Should these policies differ across the two presented cases? Why/why not?

Are there any other things that need to be implemented by aged care facilities to allow for owners to keep their assistance dog in the facility?

Are there any relevant bodies that should be involved in ensuring these policies are being upheld?

Is there any other information you would want to know about the cases that would affect your decision?

On completion of all focus groups, discussions were transcribed with identifying data removed. Data was summarized (See ‘2.4 Analysis’) and questions that did not have agreement had their various responses input into questionnaire format for ranking, using Qualtrics. This data was then collated and analysed through examination of the means and standard deviations from the Qualtrics data output.

2.4. Analysis

The initial focus group data was examined by the author, with key points identified and summarized, with similar or related responses combined for each question. For Questions 1 and 2, sufficient deliberation and agreement was achieved during the focus groups. For Question 3, two key subthemes were identified and included in the questionnaire as two independent answer lists for ranking by importance. Question 4 responses were input for ranking by importance with no subthemes. Finally, Question 5 had three key subthemes identified, which were input for independent ranking. Subsequent participant data from this questionnaire was then analysed using the Qualtrics output. Ranking was from 1 (most important) to the highest number, depending on the number of responses to rank (least important). Overall order of importance for each question or sub-question was established through the mean ranking response. That is, the lowest ranking mean was considered the most important response, the second lowest the second most important, and so on.

4. Discussion

The current study aimed to use deliberative democracy to explore whether older adults with assistance dogs should be allowed to retain their dog when they relocate to an aged care facility, and what factors should impact this decision (e.g., dog size, care abilities). Further, if they were allowed to retain their dog, what would be the best practice to allow for an effective transition and continued support within the aged care facility.

The question of whether older adults should be allowed to retain their dog when they relocate to an aged care facility is deceivingly complex. At first glance it seems like a simple yes, particularly given the numerous and far-reaching benefits highlighted in the research [

1] and the legislation which is designed to prevent separation in the context of accommodation provision [

2,

3]. However, the results indicated that there is much to consider from the perspective of the owner, the dog, and the aged care facility to protect the best interests, safety, and wellbeing of all involved. Further, this needs to be grounded in sufficient policies and procedures based on objective measurement to minimise discrimination or ageist assumptions. Specifically, it was found that assessment should begin prior to relocation and be an ongoing process, including whether the owner is able to care for the dog, whether the dog’s welfare is maintained, and initially whether the aged care facility is sufficiently and safely able to house the dog. While this seems daunting, the discussion highlighted some tools, such as the CAMSRMT or SAFE [

9,

10], can be easily implemented. Further, many aged care facilities already maintain care plans for residents, which could be adapted to include dog care. So, while this may take some time to initially establish, ongoing assessment and record keeping would be achievable with minimal time or financial burden to the aged care facility.

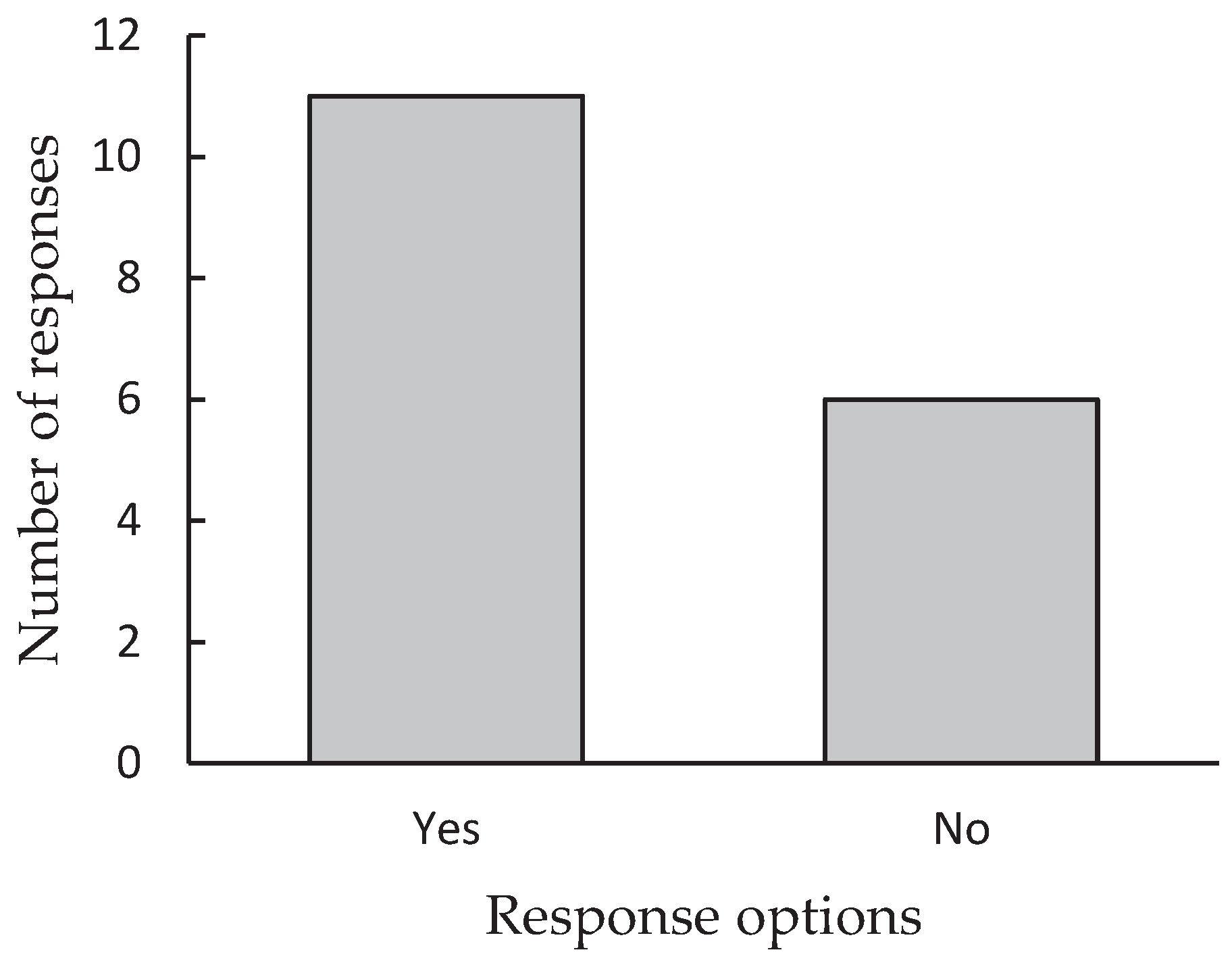

On consideration of what factors should impact the decision, all participants unanimously agreed that policies should not differ across the case studies. This was noted to prevent any other inadvertent discrimination, and to encourage decisions made on a case-by-case basis guided by objectivity. However, it was later raised that there were a number of factors that would influence this decision from a person, dog, and owner-dog perspective. The most important person factor was ‘how traumatic is it for people to give up their dog?’. While there may be some who see their dog as a tool that is no longer necessary, research suggests that this may indeed be traumatic [

6] and could be established through a discussion with the owner. Other factors alluded to how unwell the person is, severity of illnesses or disability, comorbidities, and availability of friends/family to assist. These are all important factors for all parties involved, which could be addressed by the aforementioned initial and ongoing assessments and having a sufficient care plan in place. It was also noted that alternatives could be considered, such as the cane. But taking this example, it has been found that those who have used a guide dog for a prolonged period may not be as proficient with a cane due to lack of practice so may not be easily implemented [

12]. Considerations around the dog, such as manners and behaviours, training, and breed issues should also be assessed for suitability. While ideally factors such as dog size should not prevent an owner from relocation with their dog, it must be considered that some facilities simply cannot accommodate due to limited physical space. Thinking about the owner-dog relationship again the most important factor deliberated was the cost of separation. Not just because this loss could be profound [

6], but because losing their dog could also lead to a quicker deterioration of health. Given that the health of older adults without dogs has been found to be related to faster deterioration of health, it is reasonable to consider that the compounding issue of grief could lead to further health deterioration [

13].

The third part of the study’s aim is predictably the most in-depth; considering what would be the best practice to allow for an effective transition and continued support within the aged care facility. However, it is arguably the most crucial, as it has the potential to guide best practices for future policies within aged care facilities, to facilitate owners in keeping their assistance dog wherever possible. Further, it became evident during the discussions that these policies should not just look at what to do where the owner is able to keep their dog, but also what needs to be put in place where they cannot. As already mentioned, the first step would be to ensure policies outline objective assessments to assess suitability. Thus, the following will discuss further policies and procedures in the context of where owners have the ability or limited ability to care for their dog, and where they are unable to keep their dog, followed by other key considerations.

Where owners are allowed to keep their dogs, it is important to consider the ongoing needs, safety, and welfare of the dog and owner, as well as what to do where unexpected factors arise. It should also be considered that even when the owner is able to care for their dog it may not provide the same utility. Thus, there may be the possibility for retraining (e.g., retraining a hearing dog to alert the owner to a new set of sounds). Nevertheless, key points raised and deliberated were the need for a general animal care plan, and an animal risk management and emergency directive. The general animal care plan should be developed in conjunction with the owner, to establish services needed and any care that should be undertaken by the owner. Where the owner is fully capable, this should be a relatively simple process that can be reviewed periodically as needed, or where an unexpected event occurs (e.g., health deterioration). Where the owner has limited capacity to care for their dog, this plan could include additional assistance depending on their needs, and who will provide that assistance (e.g., a professional or friends/family). This may also include who to contact where temporary respite is needed. It was raised that some aged care facilities have additional services available to residents on a pay-per-use basis. Interestingly, the majority of participants agreed that the provision of dog care support (e.g., walking, feeding) should be a pay-for-use service in an aged care facility. Given that many owners may require assistance, of only periodically, and the limited funding abilities of many aged care facilities, this could be a simple answer to provide a necessary service at no extra cost to the facility. Alternatively, it was raised that there were three other possibilities, including the recruitment of volunteers, which would be no extra cost, the employment of an animal care staff member (particularly where there is a significant amount of dogs in the facility), or additional training to current staff to provide dog care. An animal risk management and emergency directive should also be included as part of policy, again developed in conjunction with the owner. This would prevent any confusion over where the dog should be relocated, whether temporarily or permanently, in the case of illness, hospitalisation, or death. This would not only provide peace of mind to staff, but also to owners.

An overlooked factor raised in the discussions was what to do where owners are assessed as unable to keep their dog. We know that this is often associated with a period of grief, loss, and distress [

6]. As such, there should be policy protocols in place not only for those facing separation from their assistance dog, but even those facing separation from a companion animal. This could include a transition through decreasing their time with the dog, which would also allow alternatives to be explored and practiced (e.g., cane use). Alternately, having their dog visiting periodically (where possible, such as where family adopt the dog), or having an aged care visiting companion or therapy dog that they are encouraged to engage with. The latter might be a positive decision for the broader facility, with many benefits highlighted in the literature for dog assisted therapy in aged care [

14].

Much of the focus thus far has been on the owner and dog, but it is crucial that policies and procedures should also take into consideration others within the aged care facility, such as staff, other residents, and visitors. A myriad of reasons were raised as to why others may not want to be around dogs, such as allergies or fears, so physical separation, signage, training protocols and assistance dog information would be important. Also, some visitors may bring their own dog to the facility that could interfere with an assistance dog. This also ties into the point that housing and restraint should be considered as part of policy, such as ensuring the dog is kept in the owner’s room where possible, and always leashed when outside the room. This was also raised on discussion of other factors that should be considered by aged care facilities. Namely, where many dogs are in a facility a dedicated dog-friendly floor or wing could be considered, and rooms should be configured to allow staff movement while the dog is restrained. Though it must be acknowledged that for some facilities there is just not sufficient space to maintain a dog safely or comfortably. This should thus be a key consideration as part of the initial assessment. Ideally new aged care facilities should be built with animals in mind, and older facilities could consider retrofitting (e.g., adding more access to outdoor spaces). The latter of which would highly benefit from government support, with the provision of grants, particularly to encourage facilities with limited budgets. This was unsurprisingly noted as the most important factor when considering physical space. It was also raised that the dog must be kept at a hygienic standard to manage any risks of injury (such as from long claws) or infection. This should be tied back into the policies and procedures in the dog care plan, whereby the dog receives sufficient ongoing care.

Where staff have identified a sufficient reason why they cannot be around a dog (such as allergies), other staff should be able to work with the owner instead. However, for all other staff, policies should inform sufficient training, whether mandatory or optional, on assistance dogs. It was further suggested this could include staff opting to become a ‘champion’ for assistance dogs, with specific identification like a paw emblem on their name badge. While a very different cause, the use of this idea has previously been successful in the LGBT+ space, with the use of ally training and identification (such as rainbow badges) helping provide a safe, accepting space with spreading of education [

15]. Thus, this may similarly work to encourage acceptance and support of assistance dogs in the facility, and further spread education around assistance dog use and etiquette to other residents and visitors.

Given all this, the obvious question that remains is ‘which relevant bodies should be involved in ensuring these policies are upheld?’ In order of importance from the data, aged care bodies, assistance dog organisations and dog rights organisations. This is a logical order, particularly given their relative direct involvement already. But it is important to note all should be involved to a degree. Aged care bodies would already be involved at a policy level working with aged care facilities, and thus would likely assist in policy implementation support for this case. While assistance dog organisations may not be as involved in the policies, they would often be already in contact with the owner and could be instrumental in ongoing assessment of the owner’s ability to care for the dog, the necessity of the dog (may no longer have practical utility), and the welfare of the dog. The latter leads on to dog rights organisations, who may be required where the welfare of the dog is not assessed by an assistance dog organisation, or where the dog needs to be re-homed.