1. Introduction

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is an autosomal recessive inherited disorder of phenylalanine metabolism caused by pathological variants in the phenylalanine hydroxylase (

PAH) gene, which results in a deficiency of phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) [

1]. This causes an accumulation of phenylalanine (Phe) in the blood and brain. If left untreated it can lead to a variety of clinical manifestations, including acquired microcephaly, epilepsy, severe cognitive impairment, behavioural disorders, and seizures [

2].

In Ireland, PKU is diagnosed on the national newborn bloodspot screening programme (NNBSP) since 1966, between 72 and 120 hours after birth [

3]. Treatment should begin as early as possible, ideally before 10 days of life and generally consists of a lifelong restriction of Phe intake, supplemented with a low-Phe or Phe-free synthetic amino acid formula [

4]. Upon diagnosis, patients are generally admitted to our hospital for initiation of dietary treatment and parental education. Frequent blood Phe monitoring is needed to guide dietary treatment, particularly during the first years of life [

4].

Breastfeeding (BF) has been reported to have many benefits including, e.g., reduced risk of infant mortality, lower rate of obesity, malocclusion, otitis media or asthma, and better intellectual development with higher intelligence quotients [

5]. Benefits to BF mothers may include lower rates of breast cancer, ovarian cancer, type II diabetes and postpartum depression [

5].

Infants with PKU can be partially breastfed, allowing exposure to the benefits of breast milk [

4]. Acceptable blood Phe control and growth are possible with its use [

6]. However, breastfeeding rates and duration of feeding in infants with PKU, remain lower than the general population [

7]. There is limited research investigating the maternal experience of BF an infant with PKU.

Complementary feeding is the process of introducing solid or more textured foods into an infant’s liquid-based diet. This should begin at around six months of age, to ensure acceptance of new tastes and textures and include a wide variety of foods [

8]. This is of particular importance in PKU as there are many dietary restrictions. A more concentrated SP is usually introduced at 6 months to ensure adequate total protein intake without affecting appetite for solid food [

9].

The aim of our study was to describe the infant feeding and complementary feeding practices an Irish patient cohort. Our survey also aimed to explore mothers’ of infants with PKU and their experience of BF. We wanted to determine the factors which affected early BF cessation. We also aimed to understand the challenges faced by parents, whilst complementary feeding a child with PKU. This information will be used to improve our service delivery to patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Retrospective chart review

A retrospective review of dietetic patient records was performed at the National Centre for Inherited Metabolic Disorders (NCIMD) in Children’s Health Ireland (CHI) at Temple Street. The NCIMD provides metabolic care to all infants diagnosed with PKU in the Republic of Ireland. A retrospective chart review was carried out on all PKU infants with one complete year of data between August 2016 and January 2020. Our inclusion criteria were: PKU diagnosis, genetically confirmed, diagnosed on NNBSP, requiring dietary treatment, consent. Exclusion criteria were: Lack of genetically confirmed PKU diagnosis or lack of consent.

Data collected included feeding method: at diagnosis, discharge from CHI, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months of age, duration of BF and BF modalities. We also collected data on gender, age at diagnosis, Phe level at diagnosis, Phe levels for 3-52 weeks of age, age of complementary feeding and the timing of introduction of second stage SP. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee, CHI at Temple Street.

2.1.2. Parental survey

A parental questionnaire was designed using the platform ‘Survey Monkey’. Parents’ of patients identified through the chart review, were invited to participate in the survey exploring maternal experiences of BF infants with PKU, as well as their experience of complementary feeding. Informed consent was obtained for any parents willing to participate. The survey questionnaire included 61 questions; key question domains included ethnicity, previous experience of BF, impact of diagnosis of PKU on BF, facilities to BF/express, access to equipment, support/encouragement to restart BF in hospital, BF support at home, BF difficulties, duration of BF and reasons for stopping.

The second main section focused on the complementary feeding experience encompassing first foods, exposure to inappropriate complementary feeding foods, use of shop bought versus homemade prepared foods, information provided on complementary feeding, challenges faced during the complementary feeding process, main sources of stress during this period, and the use of bottle or beakers.

The full questionnaire is available as on online supplement. Response options included both forced choice and open-ended questions. The survey was developed by metabolic dietitians and pilot testing of the questionnaire was performed with a PKU parent who was not included in this study to ensure the questions were clear.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

All data was analysed using Microsoft Excel, Version 2013 and GraphPad Prism. All data are reported as means, medians, SD or numbers (%) unless otherwise indicated. The differences between the Phe levels in the BF and non-BF groups were determined by Mann–Whitney U test. Significant values were considered for p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Retrospective chart review

3.1.1. Demographic

Thirty-nine PKU infants (35.9% female, n = 15) were identified as requiring dietary treatment during the study period. Diet started at a mean age of 8.3 days +/-2.2 days. 97% (n = 38) of mothers were Irish. 79% (n = 31) of patients had been admitted to hospital for initiation of dietary treatment. Of the 6 patients not admitted, 3 had siblings with PKU, 2 had blood Phe levels <600µmol/l, indicative of early diagnosis on NNBSP, and 1 was readmitted with their mother to the maternity hospital due to post-partum complications.

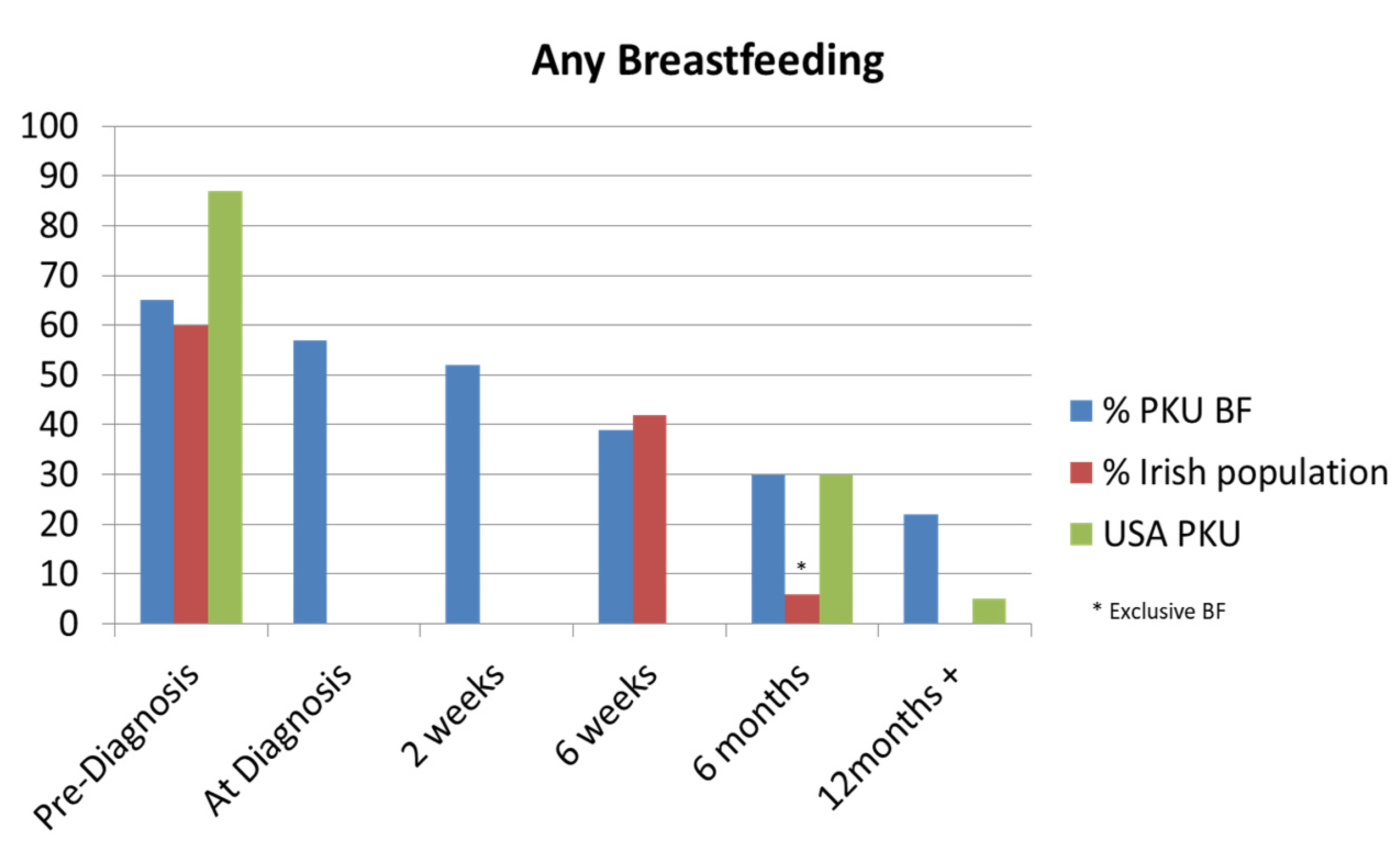

3.1.2. Feeding method

From our patient cohort, 41% (n = 16) were BF at diagnosis. In our BF patient group, the mean duration of BF was 30.2 weeks (median 23.5 weeks; range 0.8-97.5 weeks). Partial BF was the sole source of natural protein intake for a mean duration of 15.4 weeks (median 15.5 weeks; range 0.8-41 weeks). 31% of patients were using breastmilk as a source of natural protein at 4 weeks age, 26% at 3 months age, and 23% at 9 months age.

Figure 1.

Comparison of any breastfeeding in the Irish Phenylketonuria (PKU) cohort with the Irish general population [

10,

11,

12] and an American PKU study [

13].

Figure 1.

Comparison of any breastfeeding in the Irish Phenylketonuria (PKU) cohort with the Irish general population [

10,

11,

12] and an American PKU study [

13].

The traditional method of prescribed amount of Phe-free infant formula followed by breastfeeds to appetite was advised in 94% of our cohort. One patient followed a method of alternating between Phe-free infant formula and BF.

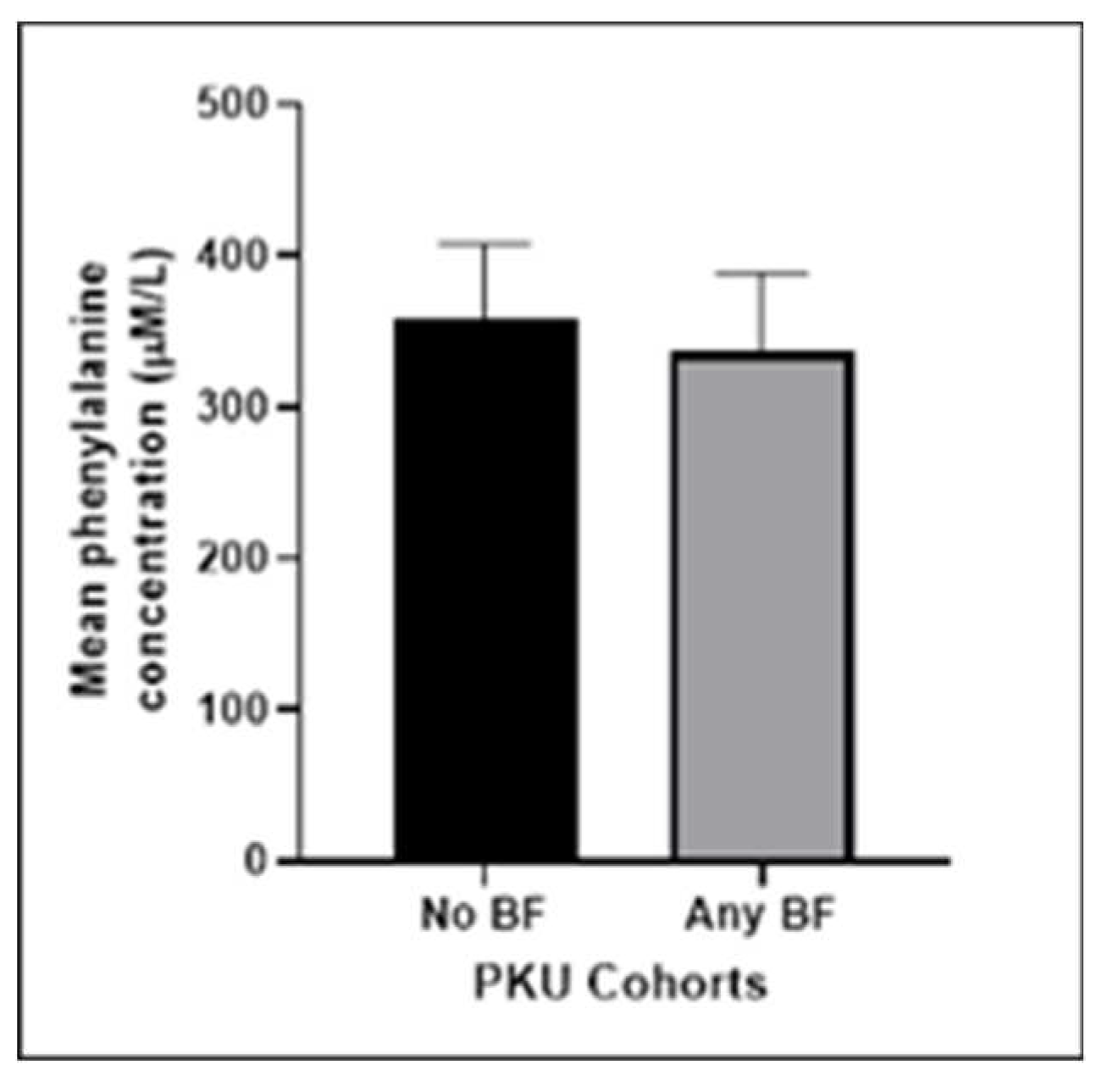

We compared the mean Phe results of the BF and non-BF groups. The BF group had marginally better metabolic control compared to the non-BF group. However the difference between the means did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.0705).

Figure 2.

Mean phenylalanine concentration (μmol/L) of our PKU cohort comparing our non-breastfeeding group with those who did some breastfeeding post diagnosis (p=0.0705). .

Figure 2.

Mean phenylalanine concentration (μmol/L) of our PKU cohort comparing our non-breastfeeding group with those who did some breastfeeding post diagnosis (p=0.0705). .

3.1.3. Complementary feeding

The mean age of commencing complementary feeding was 21.2 weeks (median 22 weeks; range 14.5 - 26.5 weeks). One infant was started too early at 14.5 weeks. All patients were offered and attended an appointment to discuss complementary feeding before commencing. A second stage SP was introduced at a mean age of 33 weeks. The majority of patients were given a paste style SP as their first option.

3.2. Parental Survey results

3.2.1. Breastfeeding responses

The response rate to the parental survey was 23/39 (59%). Of the participants, 43% reported having previous experience with BF their older children. At the time of diagnosis, 65% (n = 15) of respondents were BF mothers. However, five mothers stopped BF due to their child’s PKU diagnosis. Feedback provided by the respondents, as shown in

Table 1, revealed the reasons why they continued or discontinued. Reasons cited for discontinuing included wanting to feel in control of the amount of natural protein being given, while others found combination feeding burdensome. Some mothers reported feeling stressed due to their inexperience, coupled with the stress of the diagnosis.

The majority of BF respondents 77% (n = 10) reported that hospital facilities were supportive of BF. However, 23% (n = 3) reported a lack of privacy to express, with one reporting a delay in getting a BF pump. 85% (n = 11) reported experiencing BF difficulties, including poor supply, breast and nipple pain, poor attachment, blocked duct, delay in feeding due to premature birth, tongue tie, and complications with over supply as a result of tandem feeding with Phe-free formula, lack of BF support in the time between PKU diagnosis and admission to hospital. 69% (n = 9) sought out BF advice or support. Their main source of support included metabolic dietitians, husband/partner, midwives, lactation consultant, other mothers who had breastfed their children with PKU and online support. 89% (n = 8), described this support as either extremely or very helpful with 11% (n = 1) describing it as somewhat helpful.

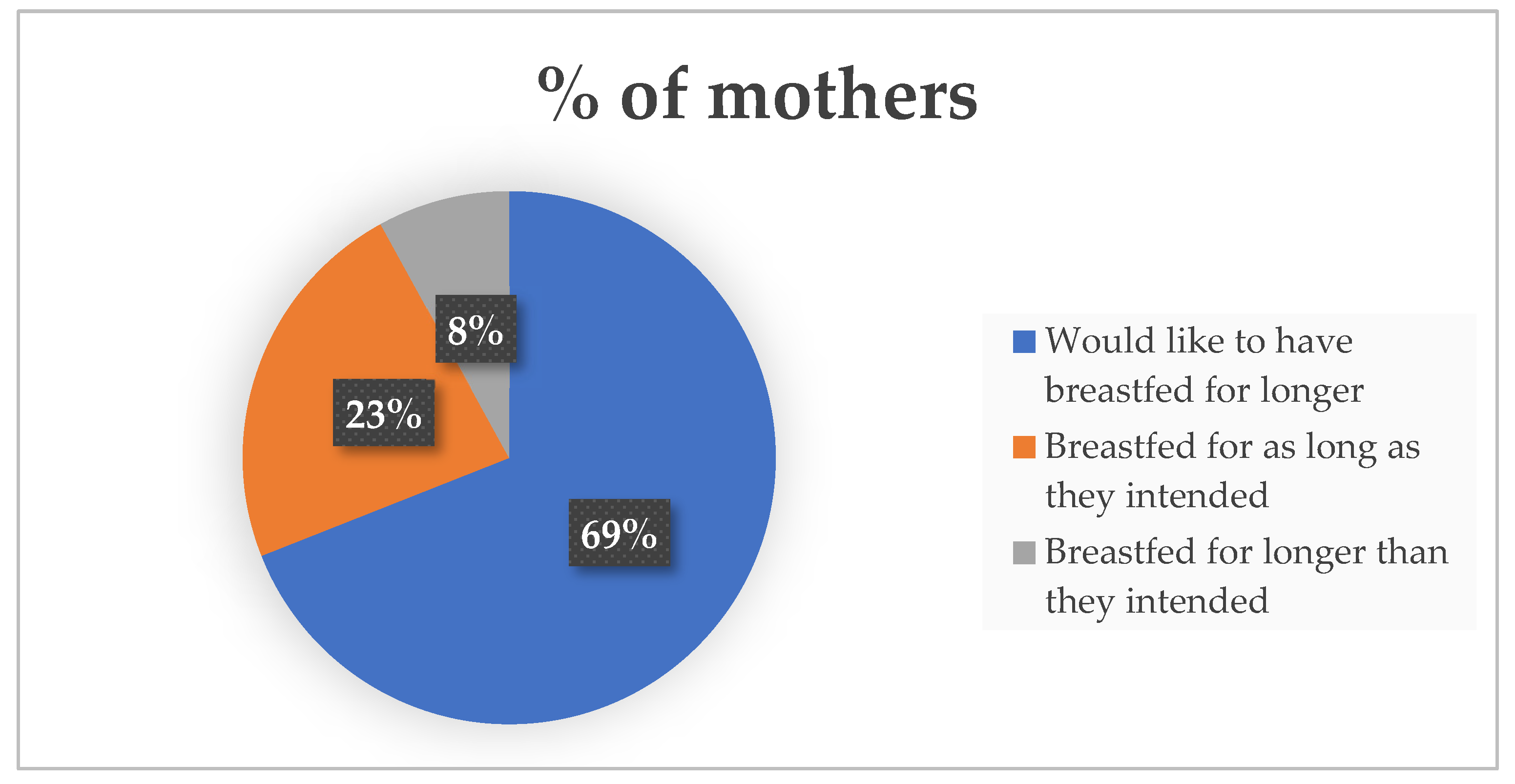

Figure 3.

Maternal feeling regarding the duration of their breastfeeding journey.

Figure 3.

Maternal feeling regarding the duration of their breastfeeding journey.

PKU related reasons for stopping included PKU diagnosis, poor supply, nipple confusion, maternal health/stress, quantifying natural protein intake, convenience, and pressure from the metabolic team.

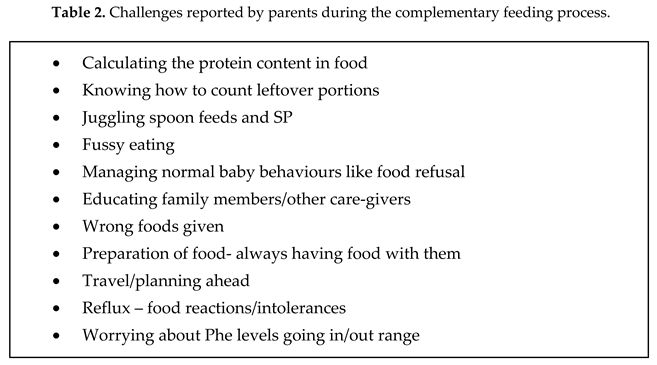

3.2.1. Complementary feeding responses

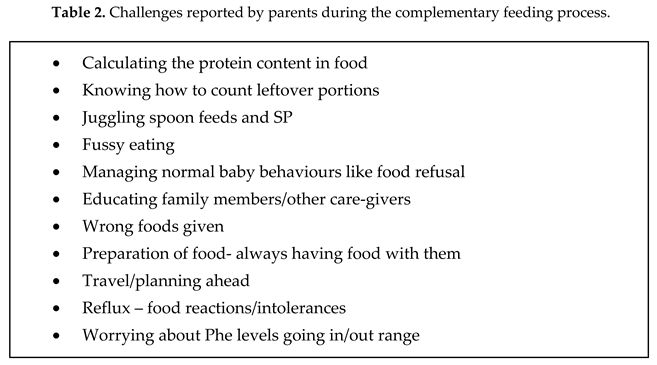

The responses to questions on complementary feeding were answered by 91% (21/23). 71% (n = 15) started with puree vegetables as the first food offered. 25% of respondents had exposure to one or more inappropriate foods including crisps, sweets, biscuits, sugary cereals, ice cream before the age of 1 year. 95% (n = 20) mostly prepared homemade baby foods and 62% (n = 13) sometimes used pre-made baby foods. Elements of a baby-led approach to complementary feeding were incorporated by 90% (n = 19). With regards to complementary feeding information, 95% (n = 20) of respondents were satisfied with the standard of information provided by the metabolic team. Over half of respondents (n = 11) reported challenges during the complementary feeding process. Stress during this period was reported by 81%. The challenges are listed in Table 2. (n = 17).

62% (n = 13) were still using a bottle for the SP beyond one year old and 43% (n=9) were still using a bottle for the synthetic protein beyond 18 months. This is despite the majority of parents (62% n=13) introducing a sippy cup at around six months and advice to wean off the bottle around the age of 12 months.

4. Discussion

In our chart review we found dietary treatment was started at a mean age of 8.3 days. This aligns with the recommendation in the European PKU guidelines that treatment should start as soon as possible, ideally before 10 days of age [

4]. Our centre’s standard procedure is to admit new patients diagnosed on NNBSP for further diagnostic work-up and commencement of treatment with MDT input, with exceptions made for siblings of known PKU patients. We explored parent’s experiences of their hospital admission through a parental survey questionnaire in our cohort of PKU patients. Our findings showed that the PKU population had lower rates of BF compared to the general Irish population at three months (26% v 35.4%) [

10]. However, at 6 months, the PKU group had higher rates of BF than the general population [

11]. It’s worth noting that published BF figures in Ireland are limited, and our figures compared mothers who were partially BF with those who were exclusively BF at the same age [

12].

Our PKU BF duration was also compared with an audit completed in our centre in 2006-2007, which showed an improvement in mean duration from 15.8 weeks to 30.2 weeks. This improvement is encouraging for our management of PKU. We cannot influence the BF initiation rates, however our role is key to supporting continuation of BF beyond the diagnosis of PKU. Our finding would suggest that additional metabolic multidisciplinary (MDT) support is needed to overcome the stress of combined feeding and dealing with a new diagnosis. Reassurance and promotion of the benefits of BF, specifically in PKU, appears to have influenced some mother’s decision to persist with BF.

Our results suggest that metabolic control is as good in BF patients as it is in those who are formula fed although this finding did not reach statistical significance. A similar outcome is described in Kose et al where Phe levels in a cohort of 26 infants were found to be better controlled when compared to the bottle-fed group [

14]. These findings are worth highlighting to counter the parental and medical belief that it is more difficult to control blood Phe levels when BF. Breast milk is the best source of nutrition for infants, and this is especially important for babies with PKU as breast milk contains lower levels of Phe than formula [

4].

Complementary feeding amongst our PKU cohort is meeting current guidelines of commencing between around six months but not earlier than 17 weeks [

8]. Only one infant was started too early at 14.5 weeks, despite all patients being offered a clinic appointment prior to starting complementary feeding. Transition to a second stage SP should ideally happen upon commencement of complementary feeding to help reduce fluid volumes and increase appetite for solids [

9]. However, we found that a second stage SP was introduced at a mean age of 33 weeks. The majority of patients were given a paste style SP as their first option. One of the main reasons for delayed introduction of a second stage SP is the overwhelming amount of dietary components which parents are trying to balance during this period.

The parental survey results showed that the majority of respondents experienced BF difficulties and sought out BF advice or support. Their primary sources of support included lactation consultant, partners, midwives, other mothers who had breastfed their children with PKU, metabolic dietitians and online support. Despite the challenges faced, the majority of respondents would like to have breastfed for longer. In order to enhance our breastfeeding rates, it is essential that we carefully examine all the reasons provided for discontinuing breastfeeding. This is particularly crucial since 69% of the respondents expressed a desire for a longer breastfeeding duration. We also noted the impact of the introduction of protein containing foods on continued BF. It is vital to encourage BF throughout the complementary feeding stage and not to see it as a time to begin weaning from the breast.

BF rates among mothers whose babies have PKU can be improved through education and support. Suggestions to improve BF continuation and duration include active promotion of the benefits and suitability, collective efforts of all MDT members in aiding, and alleviating maternal concerns, access to lactation consultant and peer support. Connecting mothers with other mothers who have successfully breastfed their baby with PKU can be a valuable source of support. This can be done through support groups, online forums, or other types of peer support networks. Our new national children’s hospital, which is due to open in 2024, will address issues some of our mothers faced concerning inadequate privacy to express breastmilk. It will provide individual rooms for patients and their parents. This aligns with one of the objectives of the WHO/UNICEF Baby-Friendly Initiative [

15].

A recurring issue reported by new mothers since our study is the inadequate provision of feeding information from local maternity hospitals during the period between PKU diagnosis and admission to the metabolic centre. This lack of information is a significant source of stress for families and may impact on the mother’s decision to continue BF. Many mothers are unfamiliar with PKU and its management which highlights the importance of education on the condition. Providing such education can help mothers feel more empowered and confident in their ability to breastfeed their baby with PKU.

Healthcare providers play a critical role in supporting mothers who want to breastfeed their baby with PKU. This includes providing guidance on BF techniques, monitoring the baby's growth and development, and helping to manage any challenges that arise. We acknowledge the importance of additional education and training regarding breastfeeding assistance for the entire MDT. While BF is the ideal choice for babies with PKU, it may not always be possible or practical for some mothers. Providing information on alternative feeding options, such as expressing breast milk can help ensure that all babies with PKU receive the proper nutrition they need.

Our survey revealed our parents are establishing healthy eating habits from the early stages, with 71% of respondents initiating their babies' solid food journey with pureed vegetables. Furthermore, a very high proportion of respondents prepared homemade meals each day. This is in contrast to a study among the general population in the United Kingdom which reported, 72% of seven to nine-month-olds and two thirds (67%) of 10-11-month olds had eaten a commercial baby or toddler meal for their main meal of the day [

16]. This may reflect our dietetic efforts to promote home-prepared meals as a means to build healthy dietary habits from the earliest stages.

In our experience, building healthy dietary habits early in life and with MDT input is beneficial for long-term compliance and in light of the complexity of PKU management [

17].

Over half of the respondents in our survey reported challenges during the complementary feeding process, such as food refusal and difficulty in calculating the protein content of foods. Despite attending regular appointments to discuss this process, some parents still use inappropriate foods for their child. Delayed introduction of a second stage SP may contribute to long-term bottle use for SP. Therefore it is important to improve education and support in making healthy food choices and address the challenges around long-term acceptance of SP.

Since conducting our study we have made improvements to our complementary feeding resources, this is despite 95% of respondents being satisfied with the standard of information they received. Our resources now include troubleshooting advice, practical recipes for integrating protein exchanges, visual guides and healthy eating guidelines. Previously, the parents may have seen a different dietitian at each clinic visit. We have changed our practice to assign a lead dietitian to guide parents through each stage of complementary feeding. This should promote consistency and aid in the introduction of second stage SP to help reduce long-term reliance on bottles. We recognise the importance of synthetic protein as a crucial part of PKU treatment and maintaining good metabolic control. To support parents struggling to get their children to take SP, we collaborate closely with our MDT particularly our psychologists and nursing staff; our patients also had regular medical reviews. We understand that this can be a challenging aspect of treatment, and we aim to provide families with the necessary resources and support to promote successful adherence. We also acknowledge that PKU is well-studied condition, and that further challenges arise for patients of other inborn disorders of protein metabolism who may be at risk of acute metabolic crises. However, further efforts should be made to support partial BF where medically possible.

Our research was the first to examine BF rates among the Irish PKU population. We also examined the barriers and solutions to preserving BF through the parental survey. This has provided unique insights into the influence of the messaging around BF at the time of PKU diagnosis. Our analysis on the stable Phe control in BF group further supports the recommendation of continued BF. Our complementary feeding section of the parental survey was the first of its kind. It has given us vital feedback on the daily challenges parents’ face which are unique to PKU. This insight has already changed our practices and our educational material to lessen the burden of care for parents.

Some limitations of our study include the small patient numbers. Demographic data on the parent groups in terms of age, education, marital status and employment was not considered. These may have had an impact on BF duration and continuation. Our survey was not validated but we did engage a parent who had previously BF to review it prior to its roll-out. We had hoped to do a semi-structured interview, which may have revealed more specific details about the challenges faced by parents. However this wasn’t possible due to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on staffing and clinic visits within our service.

5. Conclusions

BF rates are increasing in the Irish cohort of infants diagnosed with PKU. However, barriers to continuation of BF exist and are more complex in PKU. Our study has provided insight into the parental experiences of BF and will improve the quality of care needed to support our families. A multifaceted approach that includes education, support, and flexibility in feeding options is needed. By working together with healthcare providers, peer support networks, and other resources, mothers can feel confident in their ability to provide their baby with the best possible start for their infant feeding. The introduction of complementary feeding is happening at an appropriate time for most of the Irish cohort of patients diagnosed with PKU. However more education and support is needed to minimise parental stress and anxiety throughout this journey.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and investigation, Jane Rice, Jenny McNulty and Teresa Gudex; methodology, Jane Rice, Jenny McNulty and Teresa Gudex; data curation, Jane Rice and Jenny McNulty; software and formal analysis, Jane Rice, Jenny McNulty and Ina Knerr; writing - original draft preparation, Jane Rice and Jenny McNulty; validation and reviewing, Ina Knerr, Meabh O’Shea and Teresa Gudex; resources, Ina Knerr.

Funding

Temple Street Foundation, Children's Health Foundation, Dublin, Ireland, Grant/Award Number: RPAC 1902; Children's Health Ireland.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Children’s’ Health Ireland Temple Street (19.018 on 12/03/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the parents who completed this questionnaire and to those who gave feedback on the initial questionnaire drafts. We are very grateful to the entire multidisciplinary team in our centre involved in patient care, particularly the dietetic, nursing, medical and psychology teams, and the team in the metabolic and newborn screening laboratories.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Elhawary, N.A., AlJahdali, I.A., Abumansour, I.S. et al. Genetic etiology and clinical challenges of phenylketonuria. Hum Genomics 16, 22 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ashe K, Kelso W, Farrand S, Panetta J, Fazio T, De Jong G, Walterfang M. Psychiatric and Cognitive Aspects of Phenylketonuria: The Limitations of Diet and Promise of New Treatments. Front Psychiatry. 2019 Sep 10;10:561. PMID: 31551819; PMCID: PMC6748028. [CrossRef]

- HSE. Available online:https://www.hse.ie/eng/health/child/newbornscreening/newbornbloodspotscreening/information-for-professionals/a-practical-guide-to-newborn-bloodspot-screening-in-ireland.pdf (accessed on 02/12/2022).

- Van Wegberg, A.M.J.; Macdonald, A.; Ahring, K.; BéLanger-Quintana, A.; Blau, N.; Bosch, A.M.; Burlina, A.; Campistol, J.; Feillet, F.; Giz˙ ewska, M.; et al. The complete European guidelines on Phenylketonuria: Diagnosis and treatment. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grummer-Strawn, L.M. and Rollins, N. (2015), Summarising the health effects of breastfeeding. Acta Paediatr, 104: 1-2. [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn M, Bekhof J, Dijkstra T, Smit PG, Moddermam P, van Spronsen FJ. A different approach to breastfeeding of the infants with Phenylketonuria. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2003, 163, 323–326. [CrossRef]

- Zuvadelli, J.; Paci, S.; Salvatici, E.; Giorgetti, F.; Cefalo, G.; Re Dionigi, A.; Rovelli, V.; Banderali, G. Breastfeeding in Phenylketonuria: Changing Modalities, Changing Perspectives. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fewtrell M, Bronsky J, Campoy C, Domellöf M, Embleton N, Fidler Mis N, Hojsak I, Hulst JM, Indrio F, Lapillonne A, Molgaard C. Complementary Feeding: A Position Paper by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology,and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition. JPediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017, 64, 119-132. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, A., van Wegberg, A.M.J., Ahring, K. et al. PKU dietary handbook to accompany PKU guidelines. Orphanet J Rare Dis 15, 171 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Healthcare Pricing Office. Available online: https://www.hpo.ie/latest_hipe_nprs_reports/NPRS_2019/Perinatal_Statistics_Report_2019.pdf (accessed on 13/06/2023).

- HSE. Accesssed online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/performancereports/management-data-report-june-2020.pdf (accessed on 13/06/2023).

- Layte, R. and C. McCrory (2015). Growing Up in Ireland: Maternal Health Behaviours and Child Growth in Infancy, Dublin: Stationery Office / Department of Children and Youth Affairs. https://www.esri.ie/publications/growing-up-in-ireland-maternal-health-behaviours-and-child-growth-in-infancy.

- Banta-Wright. S, et al. Breastfeeding success among infants with Phenylketonuria. J. Pediatr Nurs. 2012 Aug:27(4): 319-327. [CrossRef]

- Kose, E., Aksoy, B., Kuyum, P., Tuncer, N., Arslan, N., Ozturk, Y. The effects of breastfeeding in infants with Phenylketonuria. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Unicef, UK, Baby-Friendly Initiative Standards. Available online: https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2014/02/Guide-to-the-Unicef-UK-Baby-Friendly-Initiative-Standards.pdf (accessed on 26/06/23).

- Lennox A, Sommerville J, Ong K et al (eds) (2013). Diet and Nutrition Survey of Infants and Young Children, 2011.

- Clark A, Merrigan C, Crushell E, Hughes J, Knerr I, Monavari AA, Treacy E, Coughlan A. Ten-year retrospective review (2003-2013) of 56 inpatient admissions to stabilize elevated phenylalanine levels. JIMD Rep. 2019 Mar 14;46(1):70-74. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).