Submitted:

29 June 2023

Posted:

29 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

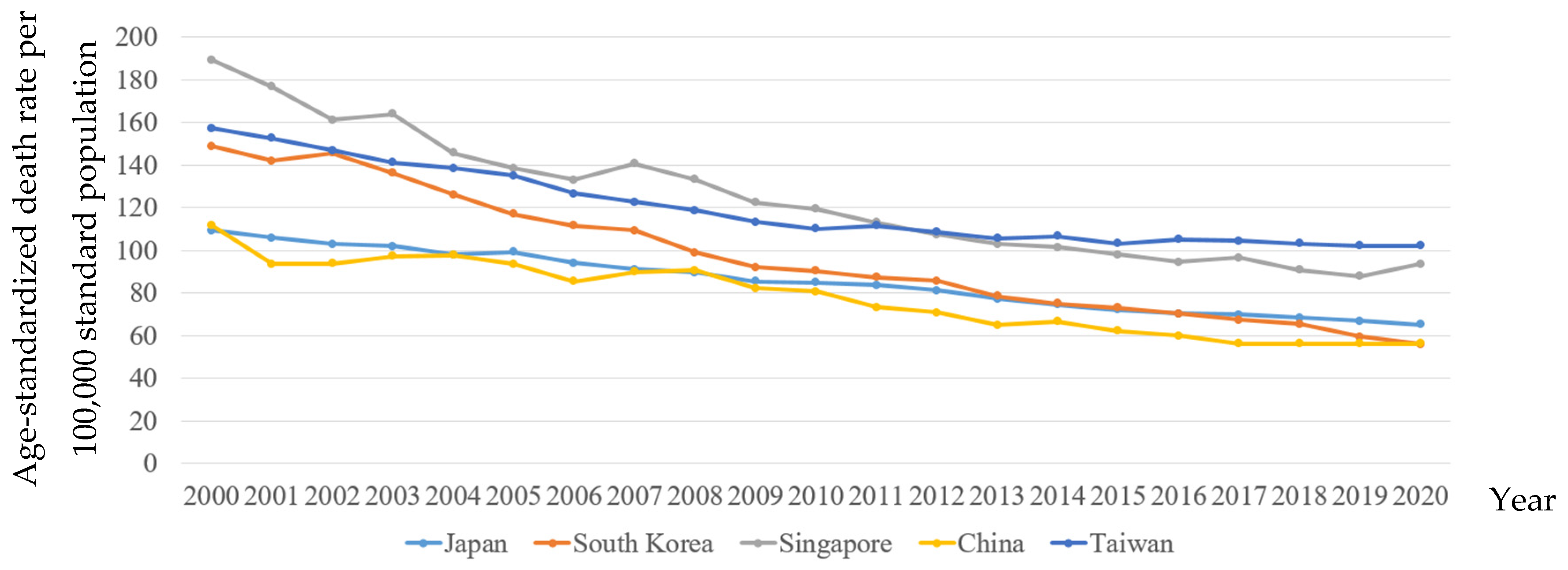

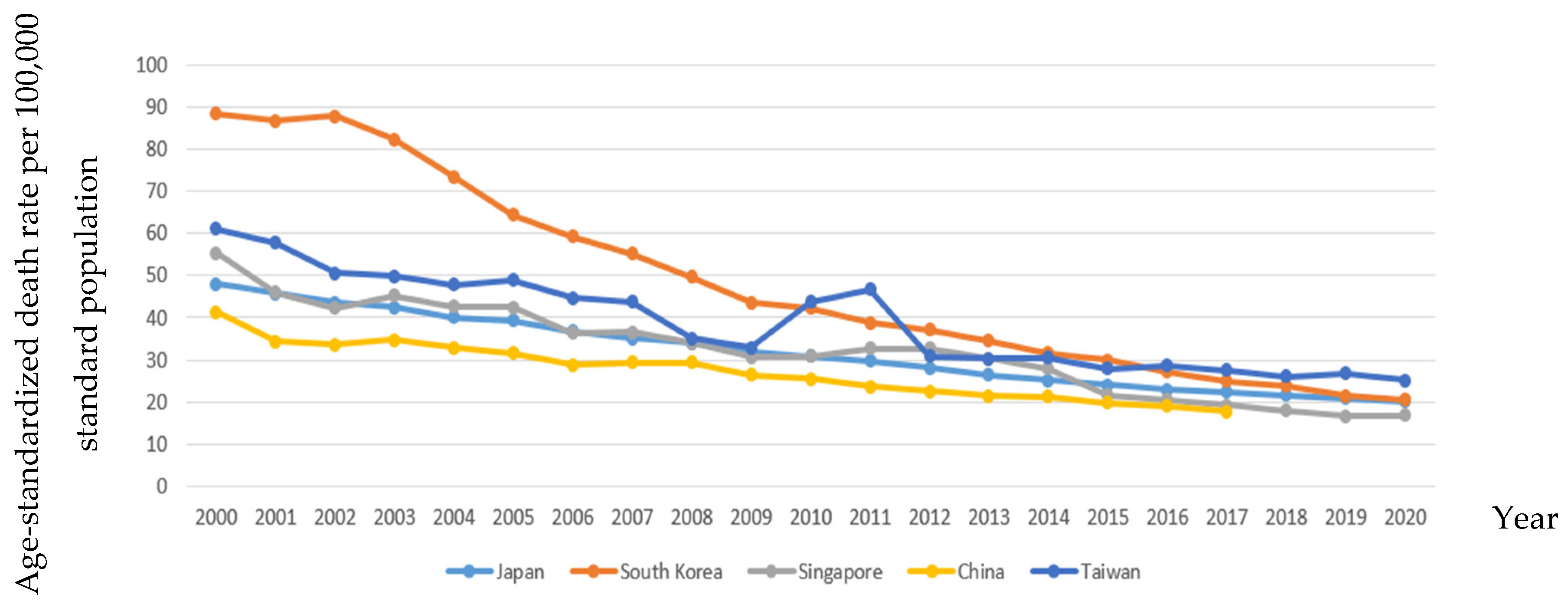

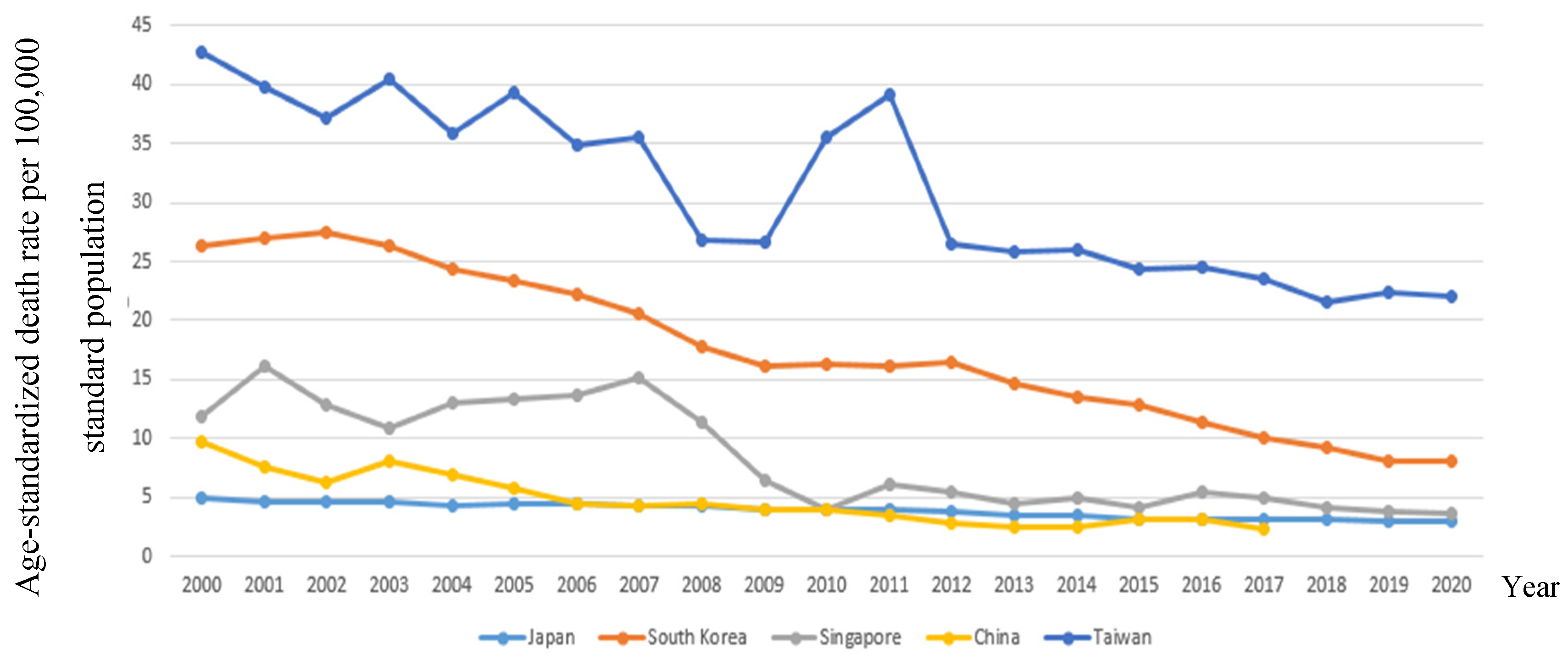

4.1. Trends and diversity of SMR for CVD and other diseases

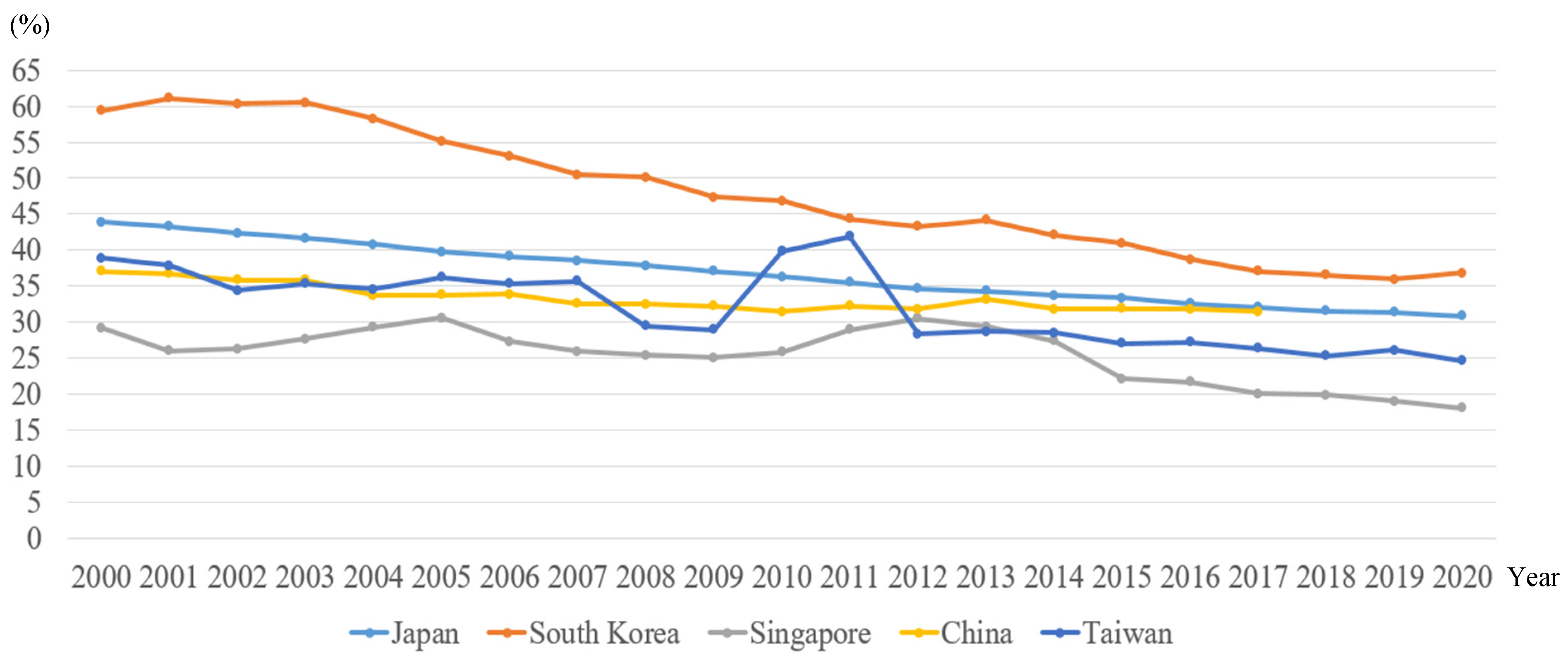

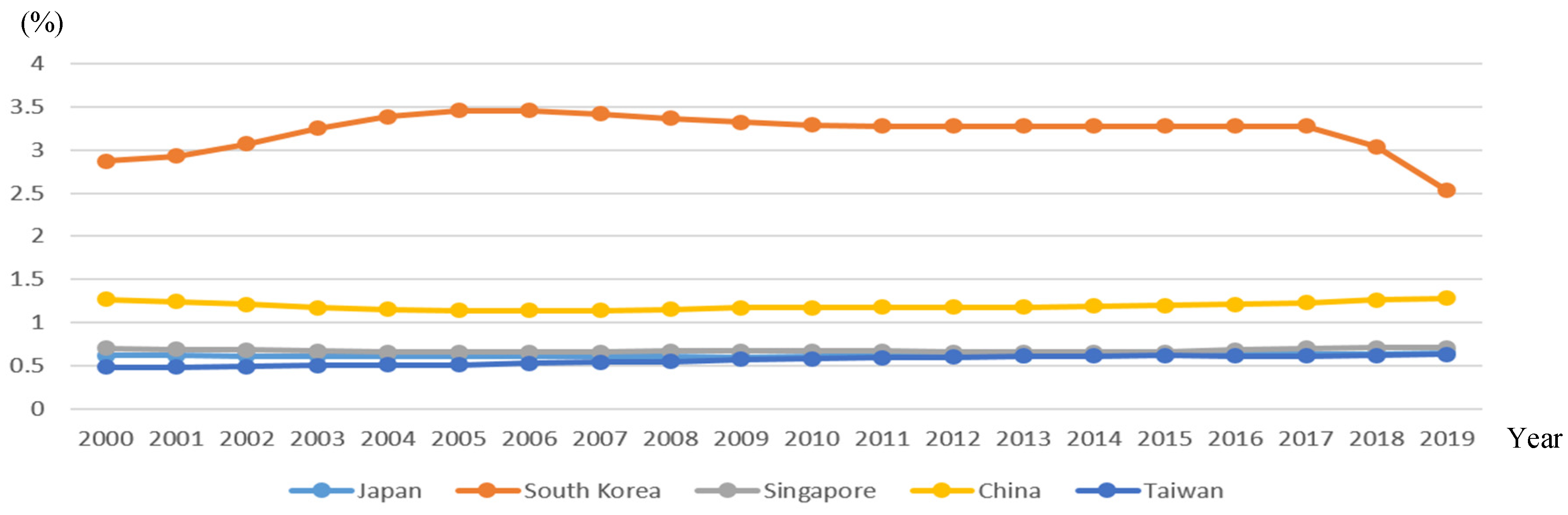

4.2. Proportion for CBD mortality contributing to CVD mortality

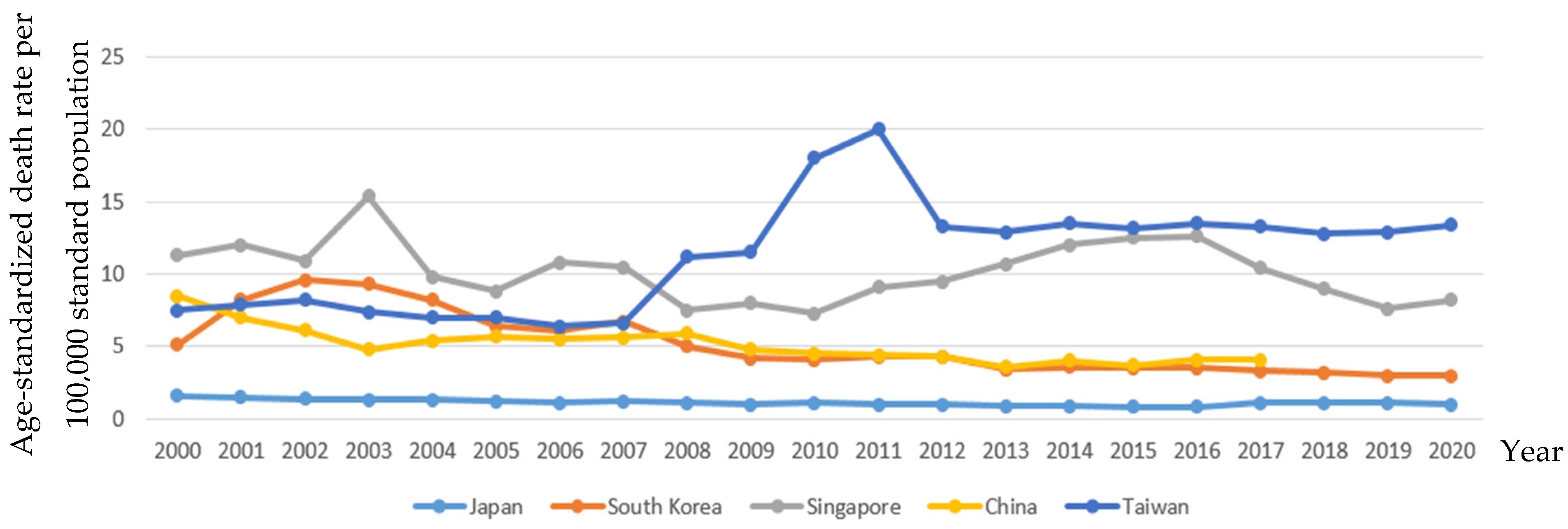

4.3. Risk factors of CVD and CBD

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Herrington, W.; Lacey, B.; Sherliker, P.; Armitage, J.; Lewington, S. Epidemiology of Atherosclerosis and the Potential to Reduce the Global Burden of Atherothrombotic Disease. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, M. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in China: current features and implications. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D. Epidemiological Features of Cardiovascular Disease in Asia. JACC: Asia 2021, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Bu, X.; Liu, J.; Wei, L.; Ma, A.; Wang, T. Cardiovascular disease burden attributable to dietary risk factors from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 32, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. Seattle, WA: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME); 2020. Available at: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbdresults-tool. Accessed May 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, K.K.; Rafiq, T. Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Prevention: A Perspective From Developing Countries. Can. J. Cardiol. 2021, 37, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, P.; Kutty, V.R.; Mohan, V.; Kumar, R.; Mony, P.; Vijayakumar, K.; Islam, S.; Iqbal, R.; Kazmi, K.; Rahman, O.; et al. Cardiovascular disease, mortality, and their associations with modifiable risk factors in a multi-national South Asia cohort: a PURE substudy. Eur. Hear. J. 2022, 43, 2831–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, S.; Joseph, P.; Rangarajan, S.; Islam, S.; Mente, A.; Hystad, P.; Brauer, M.; Kutty, V.R.; Gupta, R.; Wielgosz, A.; et al. Modifiable risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in 155 722 individuals from 21 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsunaga, M.; Yatsuya, H.; Iso, H.; Li, Y.; Yamagishi, K.; Tanabe, N.; Wada, Y.; Ota, A.; Tamakoshi, K.; Tamakoshi, A.; et al. Impact of Body Mass Index on Obesity-Related Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality; The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2022, 29, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wu, C.; Lu, J.; Chen, B.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hu, S.; Li, J. Cardiovascular risk factors in China: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e672–e681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, L.; Danos, D.; Green, C.; Cook, M.W.; Schauer, P.R.; Albaugh, V.L. Effect of high-risk factors on postoperative major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events trends following bariatric surgery in the United States from 2012 to 2019. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2022, 19, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Sakai, H.; Wakabayashi, C.; Kwon, J.-S.; Lee, Y.; Liu, S.; Wan, Q.; Sasao, K.; Ito, K.; Nishihara, K.; et al. The prevalence and risk factor control associated with noncommunicable diseases in China, Japan, and Korea. J. Epidemiology 2017, 27, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, P.B.; Liu, R.; Jia, X.B.; Kong, Y.B.; Li, F.B.; Chen, C.B.; Zhang, X.B.; Zheng, Y. Risk factors of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in young and middle-aged adults: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2022, 101, e32082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.J.; Yu, D.; Wen, W.; Shu, X.O.; Saito, E.; Rahman, S.; Gupta, P.C.; He, J.; Tsugane, S.; Xiang, Y.B.; et al. Tobacco Smoking and Mortality in Asia: A Pooled Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2019, 2, e191474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, G.E.; Kim, Y.-H.; Han, K.; Jung, J.-H.; Rhee, E.-J. ; Won-Young Won-Young Lee; On Behalf of the Taskforce Team of the Obesity Fact Sheet of the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity; Obesity Fact Sheet of the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Obesity Fact Sheet in Korea, 2020: Prevalence of Obesity by Obesity Class from 2009 to 2018. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2021, 30, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.C.; Yang, H.C.; Chang, H.Y.; Yeh, C.J.; Chen, H.H.; Huang, K.C.; Pan, W.H. Morbid obesity in Taiwan: Prevalence, trends, associated social demographics, and lifestyle factors. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Kong L, Wu F, Bai Y, Burton R. Preventing chronic diseases in China. Lancet 2005, 366, 1821–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CVD | CBD | Hypertension | Diabetes Mellitus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | RD % | AD | RD % | AD | RD % | AD | RD % | |

| Japan | ||||||||

| 2003-2008 | -12.40 | -13.84 | -8.60 | -25.37 | -0.20 | -18.18 | -0.30 | -6.98 |

| 2009-2014 | -10.90 | -14.63 | -6.60 | -26.29 | -0.10 | -11.11 | -0.60 | -17.65 |

| 2015-2020 | -6.80 | -10.45 | -3.90 | -19.40 | 0.20 | 20.00 | -0.20 | -6.67 |

| South Korea | ||||||||

| 2003-2008 | -37.10 | -37.47 | -32.70 | -65.93 | -4.30 | -86.00 | -8.50 | -47.75 |

| 2009-2014 | -16.90 | -22.53 | -11.90 | -37.66 | -0.60 | -16.67 | -2.60 | -19.26 |

| 2015-2020 | -17.00 | -30.36 | -9.30 | -0.005 | -0.50 | -16.67 | -4.90 | -61.25 |

| Singapore | ||||||||

| 2003-2008 | -30.50 | -22.88 | -11.40 | -33.63 | -7.90 | -105.33 | 0.40 | 3.54 |

| 2009-2014 | -20.80 | -20.49 | -2.90 | -0.10 | 4.00 | 33.33 | -1.50 | -30.61 |

| 2015-2020 | -4.50 | -4.81 | -4.80 | -28.40 | -4.30 | -52.44 | -0.60 | -16.67 |

| China | ||||||||

| 2003-2008 | -6.60 | -7.29 | -5.40 | -18.37 | 1.10 | 18.64 | -3.50 | -77.78 |

| 2009-2014 | -15.60 | -23.42 | -5.30 | -25.00 | -0.80 | -20.00 | -1.40 | -56.00 |

| 2015-2020 | -5.80 | -10.32 | -2.10 | -11.86 | 0.40 | 9.76 | -0.90 | -39.13 |

| Taiwan | ||||||||

| 2003-2008 | -22.59 | -19.04 | -14.90 | -42.57 | 3.80 | 33.93 | -13.60 | -0.51 |

| 2009-2014 | -6.90 | -6.48 | -2.40 | -7.89 | 2.00 | 14.81 | -0.60 | -2.31 |

| 2015-2020 | -1.03 | -1.01 | -2.70 | -10.71 | 0.20 | 1.49 | -2.30 | -10.45 |

| alcohol dependence | Smoking | Overweight | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | RD % | AD | RD % | AD | RD % | |||

| Japan | Japan | Japan | ||||||

| 2003-2008 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2005-2010 | -3.60 | -13.95 | 2000-2005 | 2.20 | 9.02 |

| 2009-2014 | 0.03 | 4.76 | 2010-2015 | -3.10 | -13.66 | 2006-2010 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2015-2019 | 0.02 | 3.08 | 2015-2020 | -2.60 | -12.94 | 2011-2016 | 1.90 | 6.99 |

| South Korea | South Korea | South Korea | ||||||

| 2003-2008 | 0.12 | 3.56 | 2005-2010 | -3.70 | -13.70 | 2000-2005 | 2.50 | 9.19 |

| 2009-2014 | -0.04 | -1.22 | 2010-2015 | -3.20 | -13.45 | 2006-2010 | 1.80 | 6.10 |

| 2015-2019 | -0.75 | -29.64 | 2015-2020 | -3.00 | -14.42 | 2011-2016 | 2.10 | 6.54 |

| Singapore | Singapore | Singapore | ||||||

| 2003-2008 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2005-2010 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2000-2005 | 1.70 | 5.63 |

| 2009-2014 | -0.01 | -1.52 | 2010-2015 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2006-2010 | 1.30 | 4.09 |

| 2015-2019 | 0.05 | 7.04 | 2015-2020 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2011-2016 | 1.5 | 4.46 |

| China | China | China | ||||||

| 2003-2008 | -0.02 | -1.74 | 2005-2010 | -0.90 | -3.60 | 2000-2005 | 3.30 | 13.69 |

| 2009-2014 | 0.02 | 1.68 | 2010-2015 | -0.70 | -2.88 | 2006-2010 | 3.00 | 10.79 |

| 2015-2019 | 0.08 | 6.25 | 2015-2020 | -0.80 | -3.40 | 2011-2016 | 3.80 | 11.76 |

| Taiwan | Taiwan | Taiwan | ||||||

| 2003-2008 | 0.05 | 9.09 | 2005-2010 | -2.90 | -14.65 | 2000-2005 | NA | NA |

| 2009-2014 | 0.04 | 6.56 | 2010-2015 | -2.70 | -15.79 | 2006-2010 | 1.05 | 2.73 |

| 2015-2019 | 0.01 | 1.59 | 2015-2020 | -4.00 | -30.53 | 2011-2016 | 8.15 | 17.30 |

| Japan | South Korea | Singapore | China | Taiwan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBD | 0.997** | 0.997** | 0.952** | 0.988** | 0.926** |

| Hypertension | 0.812** | 0.887** | 0.329 | 0.854** | -0.732** |

| Diabetes | 0.985** | 0.987** | 0.848** | 0.916** | 0.852** |

| Overweight | -0.958** | -0.990** | -0.983** | -0.972** | -0.670** |

| Smoking | 0.997** | 0.992** | -0.795** | 0.967** | 0.936** |

| Alcohol dependence | -0.700** | 0.183 | 0.135 | -0.398 | -0.978** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).