Submitted:

28 June 2023

Posted:

29 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Equine bacterial diseases of biosecurity relevance

2.1. Rhodococcus equi (Pneumonia)

2.2. Streptococcus equi subspecies equi (Strangles)

2.3. Taylorella equigenitalis (Contagious equine metritis)

2.4. Burkholderia mallei (Glanders)

3. Traditional diagnostic techniques for equine bacterial diseases

3.1. Bacterial isolation and identification diagnostic techniques

3.2. Serological diagnostic techniques

3.3. Molecular diagnostic techniques

4. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for equine bacterial diseases

4.1. Current applications of LAMP for equine bacterial disease diagnostics and surveillance

5. Current advancements in LAMP technology

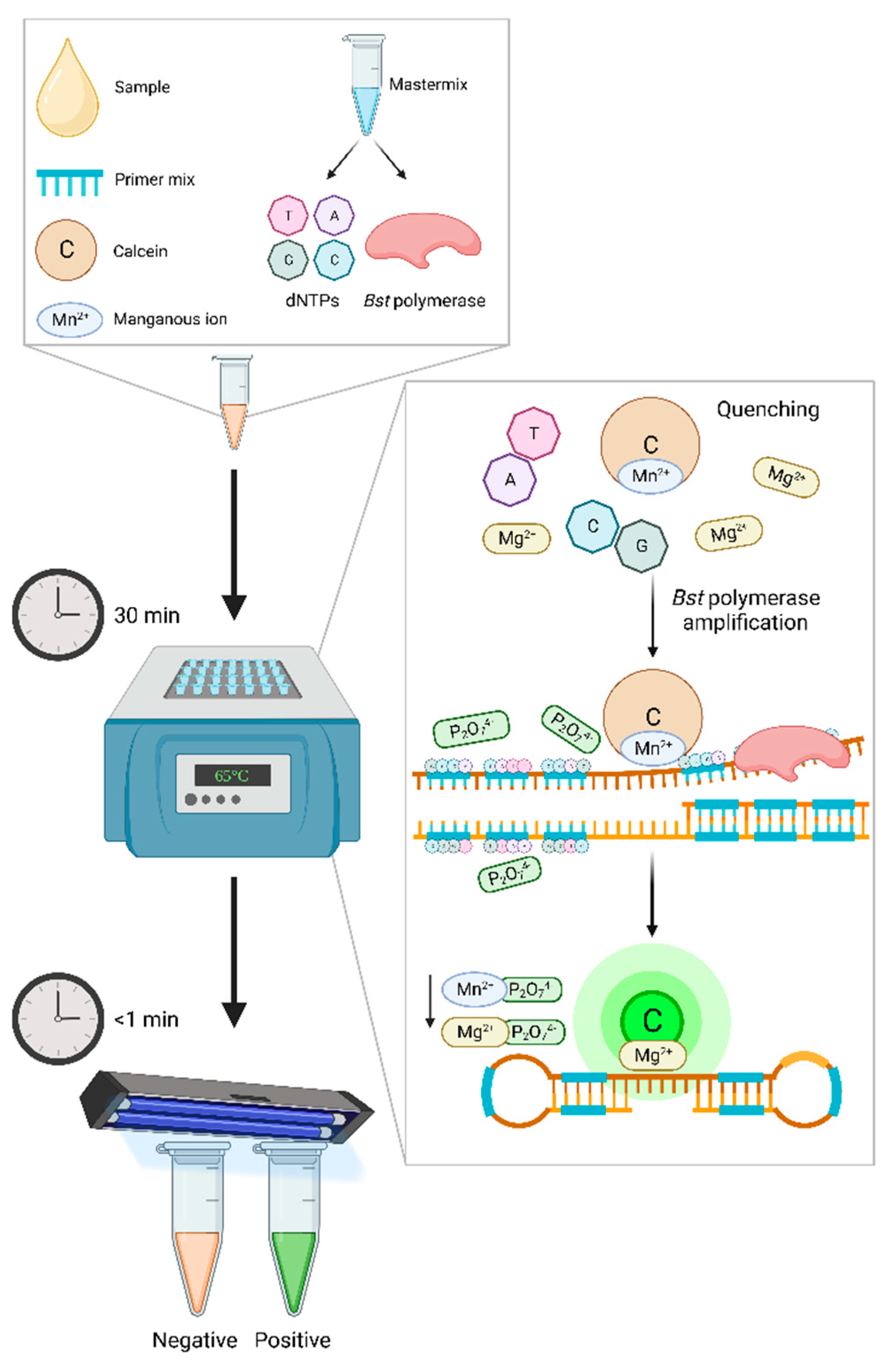

5.1. Chemical additives for the advancement of LAMP assay capabilities

5.1.1. Enhancement of LAMP assay kinetics and proficiency

5.1.2. Reduction in non-specific amplification

5.2. Advancements in LAMP monitoring techniques and technology

5.2.1. Conventional monitoring procedures commonly utilized in LAMP

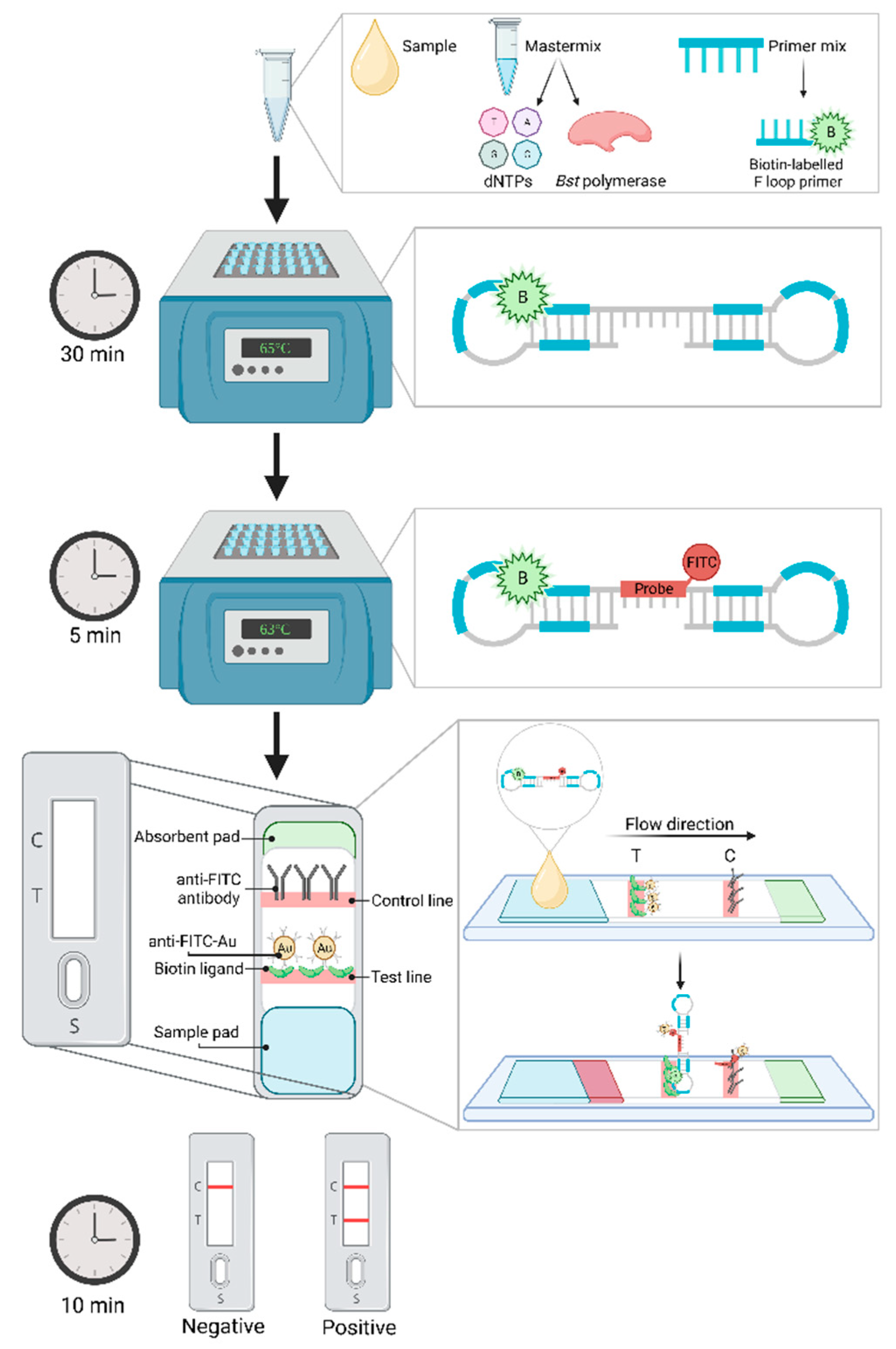

5.2.2. Lateral flow device

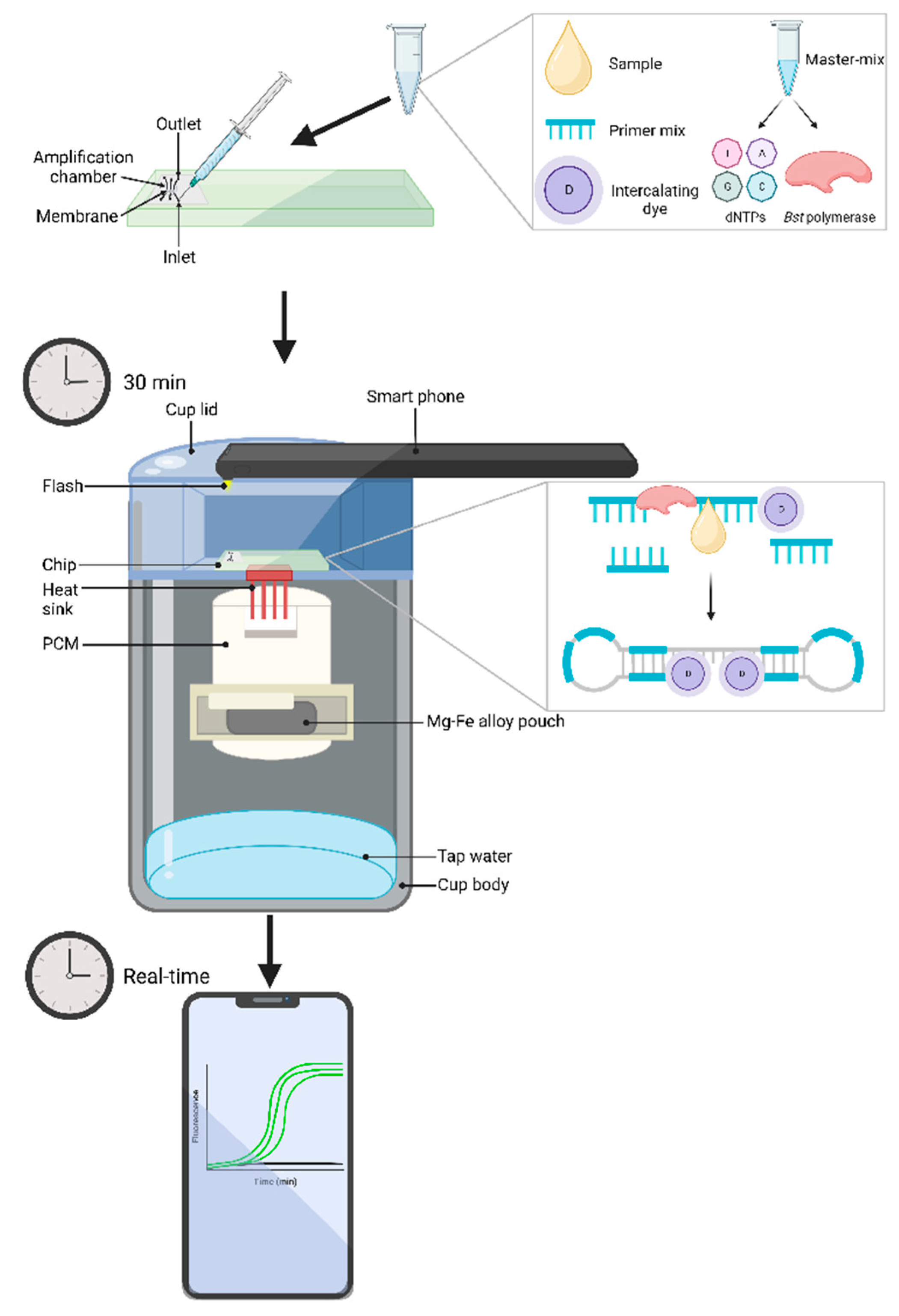

5.2.3. Microfluidic devices coupled with biochemical chips

6. Current and future priorities for equine bacterial disease diagnosis

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, G., Munstermann, S., Lam, K. Benefits and Challenges Posed by the Worldwide Expansion of Equestrian Events - New Standards for the Population of Competition Horses and Equine Disease Free Zones (EDFZ) in Countries. In Proceedings of the 81st General Session World Organisation for Animal Health, Paris, France, 26-31 May 2013, 2013.

- FAOSTAT. Production Statistics of the Food Agriculture Orginization of The United States. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QA (accessed on 03 June 2021).

- Weese, J.S. Infection control and biosecurity in equine disease control. Equine Veterinary Journal 2014, 46, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, M.; Gillett, J. Equine athletes and interspecies sport. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 2012, 47, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, T.; Bienboire-Frosini, C.; Menuge, F.; Leclercq, J.; Lafont-Lecuelle, C.; Arroub, S.; Pageat, P. The Impact of Equine-Assisted Therapy on Equine Behavioral and Physiological Responses. Animals 2019, 9, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, K.; Luba, N. The Equine Industry—Economic and Societal Impact. 2008; pp. 187-203.

- Elgåker, H.E. The new equine sector and its influence on multifunctional land use in peri-urban areas. GeoJournal 2012, 77, 591–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, M.; Münstermann, S.; de Guindos, I.; Timoney, P. Equine disease events resulting from international horse movements: Systematic review and lessons learned. Equine Veterinary Journal 2016, 48, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nixon, J. Learning about equine biosecurity. Veterinary Record 2015, 176, i-ii. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.; Thomas, S.; Mendez, D.; Chicken, C.; Carrick, J.; Heller, J.; Durrheim, D. “Prevention is the biggest success”: Barriers and enablers to personal biosecurity in the thoroughbred breeding industry. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2020, 183, 105135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartor, Y.; Gharieb, N.; Ali, W.; El-Naenaeey, E.; Ammar, A. Rapid and Precise Diagnostic Tests for S. equi: An Etiologic Agent of Equine Strangles. Zagazig Veterinary Journal 2019, 47, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Pal, V.; Tripathi, N.K.; Goel, A.K. A real-time loop mediated isothermal amplification assay for molecular detection of Burkholderia mallei, the aetiological agent of a zoonotic and re-emerging disease glanders. Acta Tropica 2019, 194, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-J.; Choi, J.-G.; Lee, S.-K.; Kim, H.-J.; Yang, S.-J.; Park, T.; Lee, S.K.; et al. Development and Application of a Multiplex Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for the Simultaneous Detection of Bacterial Aetiologic Agents Associated With Equine Venereal Diseases. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 2021, 105, 103721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoney, P.J. Infectious Diseases and International Movement of Horses. Equine Infectious Diseases 2014, 544-551.e541. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, G.E.; Baylis, M.; Archer, D.; Daly, J.M. The challenges posed by equine arboviruses. Equine Veterinary Journal 2018, 50, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knox, A.; Beddoe, T. Isothermal Nucleic Acid Amplification Technologies for the Detection of Equine Viral Pathogens. Animals 2021, 11, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Wieler, L.H.; Melzer, F.; Elschner, M.C.; Muhammad, G.; Ali, S.; Sprague, L.D.; Neubauer, H.; Saqib, M. Glanders in animals: a review on epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and countermeasures. Transbound Emerg Dis 2013, 60, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giguère, S.; Hernandez, J.; Gaskin, J.; Prescott, J.F.; Takai, S.; Miller, C. Performance of Five Serological Assays for Diagnosis of Rhodococcus equi Pneumonia in Foals. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 2003, 10, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luddy, S.; Kutzler, M.A. Contagious Equine Metritis Within the United States: A Review of the 2008 Outbreak. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 2010, 30, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhuoso, O.A.; Monroy, J.C.; Rivas-Caceres, R.R.; Cipriano-Salazar, M.; Barbabosa Pliego, A. Streptococcus equi in Equine: Diagnostic and Healthy Performance Impacts. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 2020, 85, 102870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdman, M.M.; Creekmore, L.H.; Fox, P.E.; Pelzel, A.M.; Porter-Spalding, B.A.; Aalsburg, A.M.; Cox, L.K.; Morningstar-Shaw, B.R.; Crom, R.L. Diagnostic and epidemiologic analysis of the 2008–2010 investigation of a multi-year outbreak of contagious equine metritis in the United States. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2011, 101, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoney, P.J. Horse species symposium: Contagious equine metritis: An insidious threat to the horse breeding industry in the United States1. Journal of Animal Science 2011, 89, 1552–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristula, M.A.; Smith, B.I. Diagnosis and treatment of four stallions, carriers of the contagious metritis organism—case report. Theriogenology 2004, 61, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerczek, T. Contagious equine metritis in the USA. The Veterinary record 1978, 102, 512–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fales, W.H. , Blackburn, B.O., Youngquist, R.S., Braun, W.F., Schlater, L.R., Morehouse, L.G. Laboratory methodology for the diagnosis of contagious equine metritis in Missouri [1979]. 1979; pp. 187-197.

- Hayna, J.H.; Syverson, C.M.; Dobrinsky, J.R. 155 embryo transfer success during concurrent contagious equine metritis infection Reproduction, Fertility and Development 2007, 20, 157-158. [CrossRef]

- M. Sobhy, M.; Fathi, A.; A. Abougazia, K.; R. Oshba, M.; H.R. Kotb, M. Study on Occurrence of Contagious Equine Metritis in the Genital Tract of Equine. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2019, 50, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wilsher, S.; Omar, H.; Ismer, A.; Allen, T.; Wernery, U.; Joseph, M.; Mawhinney, I.; Florea, L.; Thurston, L.; Duquesne, F.; et al. A new strain of Taylorella asinigenitalis shows differing pathogenicity in mares and Jenny donkeys. Equine Veterinary Journal 2021, 53, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aalsburg, A.M.; Erdman, M.M. Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis Genotyping of Taylorella equigenitalis Isolates Collected in the United States from 1978 to 2010. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2011, 49, 829–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sack, A.; Oladunni, F.S.; Gonchigoo, B.; Chambers, T.M.; Gray, G.C. Zoonotic Diseases from Horses: A Systematic Review. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2020, 20, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Brar, B.; Shah, I.; Ranjan, K.; Lambe, U.; Manimegalai, M.; Vashisht, B.; Khurana, S.; Prasad, G. Biotechnological tools for diagnosis of equine infectious diseases. Journal of Experimental Biology and Agricultural Sciences 2016, 4, S161–S181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacich, D.J.; Sobek, K.M.; Cummings, J.L.; Atwood, A.A.; O'Keefe, D.S. False negative results from using common PCR reagents. BMC Research Notes 2011, 4, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, A.G.; Boston, R.C.; O'Shea, K.; Young, S.; Rankin, S.C. Optimization of an in vitro assay to detect Streptococcus equi subsp. equi. Vet Microbiol 2012, 159, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.C. Biosecurity and Equine Infectious Diseases. In Encyclopedia of Agriculture and Food Systems, Van Alfen, N.K., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2014; pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Båverud, V.; Johansson, S.K.; Aspan, A. Real-time PCR for detection and differentiation of Streptococcus equi subsp. equi and Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus. Vet Microbiol 2007, 124, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidmann, P.; Madigan, J.E.; Watson, J.L. Rhodococcus equi Pneumonia: Clinical Findings, Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention. Clinical Techniques in Equine Practice 2006, 5, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notomi, T.; Okayama, H.; Masubuchi, H.; Yonekawa, T.; Watanabe, K.; Amino, N.; Hase, T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Research 2000, 28, e63–e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lowe, S.B.; Gooding, J.J. Brief review of monitoring methods for loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2014, 61, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, M.; Tsujimura, K.; Yamanaka, T.; Kondo, T.; Matsumura, T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification assays for detection of Equid herpesvirus 1 and 4 and differentiating a gene-deleted candidate vaccine strain from wild-type Equid herpesvirus 1 strains. J Vet Diagn Invest 2010, 22, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, S.S.; Ball, C.S.; Langevin, S.A.; Fang, Y.; Coffey, L.L.; Meagher, R.J. Surveillance for Western Equine Encephalitis, St. Louis Encephalitis, and West Nile Viruses Using Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0147962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, M.; Yamanaka, T.; Bannai, H.; Tsujimura, K.; Kondo, T.; Matsumura, T. Development and evaluation of a reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for H3N8 equine influenza virus. Journal of Virological Methods 2011, 178, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemoto, M.; Morita, Y.; Niwa, H.; Bannai, H.; Tsujimura, K.; Yamanaka, T.; Kondo, T. Rapid detection of equine coronavirus by reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification. J Virol Methods 2015, 215-216, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, Y.; Niwa, H.; Higuchi, T.; Katayama, Y. Development of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for detecting virulent Rhodococcus equi. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 2016, 28, 608–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, A.G.; Rankin, S.C.; O'Shea, K.; Stefanovski, D.; Peng, J.; Song, J.; Bau, H.H. Detection of Streptococcus equi subsp. equi in guttural pouch lavage samples using a loop-mediated isothermal nucleic acid amplification microfluidic device. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2021, 35, 1597–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, V.; Saxena, A.; Singh, S.; Goel, A.K.; Kumar, J.S.; Parida, M.M.; Rai, G.P. Development of a real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for detection of Burkholderia mallei. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2018, 65, e32–e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, A.; Thekisoe, O.M.M.; Yokoyama, N.; Inoue, N.; Motloang, M.Y.; Mbati, P.A.; Yin, H.; Katayama, Y.; Anzai, T.; Sugimoto, C.; et al. Development of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) method for diagnosis of equine piroplasmosis. Veterinary Parasitology 2007, 143, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummery, L.; Jallow, S.; Raftery, A.G.; Bennet, E.; Rodgers, J.; Sutton, D.G.M. Comparison of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) and PCR for the diagnosis of infection with Trypanosoma brucei ssp. in equids in The Gambia. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0237187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özay, B.; McCalla, S.E. A review of reaction enhancement strategies for isothermal nucleic acid amplification reactions. Sensors and Actuators Reports 2021, 3, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padalino, B. Effects of the different transport phases on equine health status, behavior, and welfare: A review. Journal of Veterinary Behavior 2015, 10, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, B.; Greko, C. Antibiotic resistance—consequences for animal health, welfare, and food production. Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences 2014, 119, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, R.M. Environmental disinfection to control equine infectious diseases. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 2004, 20, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, H. Spezifische infektiose Pneumonie beim Fohlen. Ein neuer Eiterreger beim Pferd. Arch. Wiss. Prakt. Tierhelkd 1923, 50, 22–38. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, M.; Alderson, G. The Actinomycete-genus Rhodococcus: A Home for the ‘rhodochrous’ Complex. Microbiology 1977, 100, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Bargen, K.; Haas, A. Molecular and infection biology of the horse pathogen Rhodococcus equi. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2009, 33, 870–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.S.; Philp, J.C.; Aw, D.W.; Christofi, N. The genus Rhodococcus. J Appl Microbiol 1998, 85, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscatello, G.; Leadon, D.P.; Klayt, M.; Ocampo-Sosa, A.; Lewis, D.A.; Fogarty, U.; Buckley, T.; Gilkerson, J.R.; Meijer, W.G.; Vazquez-Boland, J.A. Rhodococcus equi infection in foals: the science of 'rattles'. Equine Vet J 2007, 39, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, M.K.; Cohen, N.D.; Martens, R.J.; Edwards, R.F.; Nevill, M. Foal-related risk factors associated with development of Rhodococcus equi pneumonia on farms with endemic infection. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 2003, 223, 1791–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N.D.; Carter, C.N.; Scott, H.M.; Chaffin, M.K.; Smith, J.L.; Grimm, M.B.; Kuskie, K.R.; Takai, S.; Martens, R.J. Association of soil concentrations of Rhodococcus equi and incidence of pneumonia attributable to Rhodococcus equi in foals on farms in central Kentucky. Am J Vet Res 2008, 69, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, S.; Taouji, S.; Benachour, A.; Hartke, A. Resistance of Rhodococcus equi to acid pH. Int J Food Microbiol 2000, 55, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, S.; Benachour, A.; Taouji, S.; Auffray, Y.; Hartke, A. H(2)O(2), which causes macrophage-related stress, triggers induction of expression of virulence-associated plasmid determinants in Rhodococcus equi. Infect Immun 2002, 70, 3768–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giguère, S.; Hernandez, J.; Gaskin, J.; Miller, C.; Bowman, J.L. Evaluation of white blood cell concentration, plasma fibrinogen concentration, and an agar gel immunodiffusion test for early identification of foals with Rhodococcus equi pneumonia. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003, 222, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AAEP. AAEP Infectious Disease Guidelines: Rhodococcus equi; American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP): Kentucky, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold-Lehna, D.; Venner, M.; Berghaus, L.J.; Berghaus, R.; Giguère, S. Changing policy to treat foals with Rhodococcus equi pneumonia in the later course of disease decreases antimicrobial usage without increasing mortality rate. Equine Veterinary Journal 2020, 52, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillidge, C.J. Use of erythromycin-rifampin combination in treatment of Rhodococcus equi pneumonia. Veterinary Microbiology 1987, 14, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedlaya, I.; Ing, M.B.; Wong, S.S. Rhodococcus equi Infections in Immunocompetent Hosts: Case Report and Review. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2001, 32, e39–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giguère, S.; Lee, E.; Williams, E.; Cohen, N.D.; Chaffin, M.K.; Halbert, N.; Martens, R.J.; Franklin, R.P.; Clark, C.C.; Slovis, N.M. Determination of the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance to macrolide antimicrobials or rifampin in Rhodococcus equi isolates and treatment outcome in foals infected with antimicrobial-resistant isolates of R equi. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 2010, 237, 74- 81 [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giguère, S.; Berghaus, L.J.; Willingham-Lane, J.M.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Schwarz, S.; Shen, J.; Cavaco, L. Antimicrobial Resistance in Rhodococcus equi. Microbiology Spectrum 2017, 5, 5.5.14. [CrossRef]

- Chirino-Trejo, J.M.; Prescott, J.F.; Yager, J.A. Protection of foals against experimental Rhodococcus equi pneumonia by oral immunization. Can J Vet Res 1987, 51, 444–447. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, J.; Fodor, L.; Rusvai, M.; Soós, I.; Makrai, L. Prevention of Rhodococcus equi pneumonia of foals using two different inactivated vaccines. Vet Microbiol 1997, 56, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper-McGrevy, K.E.; Wilkie, B.N.; Prescott, J.F. Virulence-associated protein-specific serum immunoglobulin G-isotype expression in young foals protected against Rhodococcus equi pneumonia by oral immunization with virulent R. equi. Vaccine 2005, 23, 5760–5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, R.J.; Martens, J.G.; Fiske, R.A.; Hietala, S.K. Rhodococcus equi foal pneumonia: protective effects of immune plasma in experimentally infected foals. Equine Vet J 1989, 21, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, J.E.; Hietala, S.; Muller, N. Protection against naturally acquired Rhodococcus equi pneumonia in foals by administration of hyperimmune plasma. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 1991, 44, 571–578. [Google Scholar]

- Caston, S.S.; McClure, S.R.; Martens, R.J.; Chaffin, M.K.; Miles, K.G.; Griffith, R.W.; Cohen, N.D. Effect of hyperimmune plasma on the severity of pneumonia caused by Rhodococcus equi in experimentally infected foals. Vet Ther 2006, 7, 361–375. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, J.R.; Begg, A.P. Failure of hyperimmune plasma to prevent pneumonia caused by Rhodococcus equi in foals. Aust Vet J 1995, 72, 418–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giguère, S.; Cohen, N.D.; Keith Chaffin, M.; Slovis, N.M.; Hondalus, M.K.; Hines, S.A.; Prescott, J.F. Diagnosis, Treatment, Control, and Prevention of Infections Caused by Rhodococcus equi in Foals. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2011, 25, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordin, A.I.; Huber, L.; Sanz, M.G.; Cohen, N.D. Rhodococcus equi foal pneumonia: Update on epidemiology, immunity, treatment and prevention. Equine Veterinary Journal 2022, 54, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, A.G.; Timoney, J.F.; Newton, J.R.; Hines, M.T.; Waller, A.S.; Buchanan, B.R. Streptococcus equi Infections in Horses: Guidelines for Treatment, Control, and Prevention of Strangles—Revised Consensus Statement. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2018, 32, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.D.; Wilson, W.D. Streptococcus equi subsp. equi (Strangles) Infection. Clinical Techniques in Equine Practice 2006, 5, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, A. Streptococcus equi: breaking its strangles-hold. Veterinary Record 2018, 182, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, J.W. The streptococcus of strangles. Journal of Comparative Pathology and Therapeutics 1888, 1, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, A.S. Strangles: a pathogenic legacy of the war horse. Veterinary Record 2016, 178, 91–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piché, C.A. Clinical observations on an outbreak of strangles. Can Vet J 1984, 25, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swerczek, T. Exacerbation of Streptococcus equi (strangles) by overly nutritious diets in horses: A model for infectious bacterial diseases of horses and other livestock. Animal and Veterinary Sciences 2019, 7, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, M.C.; Goehring, L. Equine strangles: An update on disease control and prevention. Austral journal of veterinary sciences 2021, 53, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendle, D.; de Brauwere, M.; Hallowell, G.; Ivens, P.; McGlennon, A.; Newton, R.; White, J.; Waller, A. Streptococcus equi infections: current best practice in the diagnosis and management of ‘strangles’. UK-Vet Equine 2021, 5, S3–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdimuratova, K.T.; Makhamed, R.; Shevtsov, A.B. Optimization of Conditions for The Multiplex PCR for Diagnostics of Horse Strangles with Subspecies Differentiation of Streptococcus Equi Subsp Equi. Eurasian Journal of Applied Biotechnology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusterla, N.; Leutenegger, C.M.; Barnum, S.M.; Byrne, B.A. Use of quantitative real-time PCR to determine viability of Streptococcus equi subspecies equi in respiratory secretions from horses with strangles. Equine Veterinary Journal 2018, 50, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, A.G. Strangles and its complications. Equine Veterinary Education 2017, 29, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R. A closer look at strangles. Equine Health 2018, 2018, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Prescott, K.; Rogers, S. Applying the science of behaviour change to the management of strangles. UK-Vet Equine 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, L.W.; Stoy, C.P.A.; Wang, Y.; Porter, E.G.; Lu, N.; Liu, X.; Burklund, A.; Peddireddi, L.; Hanzlicek, G.; Henningson, J.; et al. Development of a nested PCR assay for detection of Streptococcus equi subspecies equi in clinical equine specimens and comparison with a qPCR assay. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2020, 172, 105887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, J.L.; Reif, J.S.; Shideler, R.K.; Small, C.J.; Ellis, R.P.; Snyder, S.P.; McChesney, A.E. Identification of carriers of Streptococcus equi in a naturally infected herd. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1983, 183, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Newton, J.R.; Wood, J.L.; Dunn, K.A.; DeBrauwere, M.N.; Chanter, N. Naturally occurring persistent and asymptomatic infection of the guttural pouches of horses with Streptococcus equi. Vet Rec 1997, 140, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Steward, K.F.; Charbonneau, A.R.L.; Walsh, S.; Wilson, H.; Timoney, J.F.; Wernery, U.; Joseph, M.; Craig, D.; van Maanen, K.; et al. Globetrotting strangles: the unbridled national and international transmission of Streptococcus equi between horses. Microb Genom 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAEP. AAEP Infectious Disease Guidelines: Strangles (Streptococcus equi subspecies equi); American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP): Kentucky, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl, S.; Båverud, V.; Egenvall, A.; Aspán, A.; Pringle, J. Comparison of sampling sites and laboratory diagnostic tests for S. equi subsp. equi in horses from confirmed strangles outbreaks. J Vet Intern Med 2013, 27, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, C.R.; Timoney, J.F.; Newton, J.R.; Hines, M.T. Streptococcus equi Infections in Horses: Guidelines for Treatment, Control, and Prevention of Strangles. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2005, 19, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christmann, U.; Pink, C. Lessons learned from a strangles outbreak on a large Standardbred farm. Equine Veterinary Education 2017, 29, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, R.E.; Harris, D.; Monge, A. How to Control Strangles Infections on the Endemic Farm. 2006.

- Pringle, J.; Storm, E.; Waller, A.; Riihimäki, M. Influence of penicillin treatment of horses with strangles on seropositivity to Streptococcus equi ssp. equi-specific antibodies. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2020, 34, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.M.; Staempfli, H.R.; Prescott, J.F.; Viel, L. Field evaluation of a commercial M-protein vaccine against Streptococcus equi infection in foals. American journal of veterinary research 1991, 52, 589–592. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eaglesome, M.D.; Garcia, M.M. Contagious equine metritis: a review. Can Vet J 1979, 20, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petry, S.; Breuil, M.-F.; Duquesne, F.; Laugier, C. Towards European harmonisation of contagious equine metritis diagnosis through interlaboratory trials. Veterinary Record 2018, 183, 96–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell D, G. Contagious equine metritis. Adv. Vet. Sci. Comp. 1981, 25, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoney, P.J.; Powell, D.G. Contagious equine metritis—epidemiology and control. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 1988, 8, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.L.; Begg, A.P.; Browning, G.F. Outbreak of equine endometritis caused by a genotypically identical strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 2011, 23, 1236–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, M.L.; May, C.E.; Keys, B.; Guthrie, A.J. Contagious equine metritis: Artificial reproduction changes the epidemiologic paradigm. Veterinary Microbiology 2013, 167, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzai, T.; Kamada, M.; Niwa, H.; Eguchi, M.; Nishi, H. Contagious Equine Metritis Eradicated from Japan. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2012, 74, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIE. Contagious Equine Metritis. In Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals (2022), 8th ed.; World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE): Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, T. Contagious equine metritis in Portugal: A retrospective report of the first outbreak in the country and recent contagious equine metritis test results. Open Vet J 2016, 6, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Allen, W.R. Memories of contagious equine metritis 1977 in Newmarket. Equine Veterinary Journal 2020, 52, 344–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duquesne, F.; Pronost, S.; Laugier, C.; Petry, S. Identification of Taylorella equigenitalis responsible for contagious equine metritis in equine genital swabs by direct polymerase chain reaction. Research in veterinary science 2007, 82, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamada, M.; Akiyama, Y.; Oda, T.; Fukuzawa, Y. Contagious Equine Metritis : Isolation of Haemophilus equigenitalis from Horses with Endometritis in Japan. The Japanese Journal of Veterinary Science 1981, 43, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, C.; Isayama, Y.; Kashiwazaki, M.; Fujikura, T.; Mitani, K. Detection of Haemophilus equigenitalis, the causal agent of contagious equine metritis, in Japan. Natl Inst Anim Health Q (Tokyo) 1980, 20, 118–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anzai, T.; Eguchi, M.; Sekizaki, T.; Kamada, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Okuda, T. Development of a PCR Test for Rapid Diagnosis of Contagious Equine Metritis. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 1999, 61, 1287–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzai, T.; Eguchi, M.; Eto, M.; Okuda, T.; Aoki, T.; Sawada, T.; Matsuda, M. Establishment and Evaluation of the PCR Test for Diagnosing Contagious Equine Metritis. Journal of the Japan Veterinary Medical Association 2001, 54, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeoung, H.-Y.; Lee, K.-E.; Yang, S.-J.; Park, T.; Lee, S.K.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, B.; Kim, Y.-J.; Park, J.-Y. First Isolation of Taylorella equigenitalis From Thoroughbred Horses in South Korea. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 2016, 47, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettle, A.N.B.; Wernery, U. Glanders and the risk for its introduction through the international movement of horses. Equine Veterinary Journal 2016, 48, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kianfar, N.; Ghasemian, A.; Al-Marzoqi, A.H.; Eslami, M.; Vardanjani, H.R.; Mirforughi, S.A.; Vardanjani, H.R. The reemergence of glanders as a zoonotic and occupational infection in Iran and neighboring countries. Reviews and Research in Medical Microbiology 2019, 30, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elschner, M.C.; Scholz, H.C.; Melzer, F.; Saqib, M.; Marten, P.; Rassbach, A.; Dietzsch, M.; Schmoock, G.; de Assis Santana, V.L.; de Souza, M.M.; et al. Use of a Western blot technique for the serodiagnosis of glanders. BMC Vet Res 2011, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernery, U.; Wernery, R.; Joseph, M.; Al-Salloom, F.; Johnson, B.; Kinne, J.; Jose, S.; Jose, S.; Tappendorf, B.; Hornstra, H.; et al. Natural Burkholderia mallei infection in Dromedary, Bahrain. Emerg Infect Dis 2011, 17, 1277–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ani, F.; Roberson, J.; Roberson, J. Glanders in horses: A review of the literature. Vet. Arhiv. 77: 203-218. 2007, 77, 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, P. Glanders: re-emergence of an ancient zoonosis. Microbiology Australia 2020, 41, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zandt, K.E.; Greer, M.T.; Gelhaus, H.C. Glanders: an overview of infection in humans. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2013, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovalev, G.K. [Glanders (review)]. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol 1971, 48, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- OIE. Glanders and Meliodosis In Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals (2022), 8th ed.; World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE): Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, C.; Miller, W.R. Human glanders: Report of six cases Annals of Internal Medicine 1947, 26, 93-115.

- Santos Júnior, E.L.D.; Moura, J.C.R.; Protásio, B.; Parente, V.A.S.; Veiga, M. Clinical repercussions of Glanders (Burkholderia mallei infection) in a Brazilian child: a case report. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2020, 53, e20200054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khakhum, N.; Tapia, D.; Torres, A.G. Burkholderia mallei and Glanders. In Defense Against Biological Attacks: Volume II, Singh, S.K., Kuhn, J.H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 161–183. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, M.; Paulos Gutama, K. Glanders: A Potential Bioterrorism Weapon Disease. American Journal of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology 2022, 10, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, D.C.; Gomes, A.S.; Tessler, D.K.; Chiebao, D.P.; Fava, C.D.; Romaldini, A.H.d.C.N.; Araujo, M.C.; Pompei, J.; Marques, G.F.; Harakava, R.; et al. Systematic monitoring of glanders-infected horses by complement fixation test, bacterial isolation, and PCR. Veterinary and Animal Science 2020, 10, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittig, M.B.; Wohlsein, P.; Hagen, R.M.; Al Dahouk, S.; Tomaso, H.; Scholz, H.C.; Nikolaou, K.; Wernery, R.; Wernery, U.; Kinne, J.; et al. [Glanders--a comprehensive review]. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr 2006, 113, 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Cravitz, L.; Miller, W.R. Immunologic Studies with Malleomyces mallei and Malleomyces pseudomallei. II. Agglutination and Complement Fixation Tests in Man and Laboratory Animals. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 1950, 86, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaso, H.; Scholz, H.C.; Al Dahouk, S.; Eickhoff, M.; Treu, T.M.; Wernery, R.; Wernery, U.; Neubauer, H. Development of a 5′-Nuclease Real-Time PCR Assay Targeting fliP for the Rapid Identification of Burkholderia mallei in Clinical Samples. Clinical Chemistry 2006, 52, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIE. Equidae. In Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals (2022), 8th ed.; World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE): Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pusterla, N.; Madigan, J.E.; Leutenegger, C.M. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction: A Novel Molecular Diagnostic Tool for Equine Infectious Diseases. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2006, 20, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, D.C.; Gomes, A.S.; Tessler, D.K.; Chiebao, D.P.; Fava, C.D.; Romaldini, A.; Araujo, M.C.; Pompei, J.; Marques, G.F.; Harakava, R.; et al. Systematic monitoring of glanders-infected horses by complement fixation test, bacterial isolation, and PCR. Vet Anim Sci 2020, 10, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprague, L.D.; Zachariah, R.; Neubauer, H.; Wernery, R.; Joseph, M.; Scholz, H.C.; Wernery, U. Prevalence-dependent use of serological tests for diagnosing glanders in horses. BMC Veterinary Research 2009, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, K.; Barker, C.; Harrison, T.; Heather, Z.; Steward, K.F.; Robinson, C.; Newton, J.R.; Waller, A.S. Detection of Streptococcus equi subspecies equi using a triplex qPCR assay. Vet J 2013, 195, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakowska, A.; Cywinska, A.; Witkowski, L. Current Trends in Understanding and Managing Equine Rhodococcosis. Animals 2020, 10, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léon, A.; Versmisse, Y.; Despois, L.; Castagnet, S.; Gracieux, P.; Blanchard, B. Validation of an Easy Handling Sample Preparation and Triplex Real Time PCR for Rapid Detection of T. equigenitalis and Other Organisms Associated with Endometritis in Mares. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 2020, 94, 103241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merwyn, S.; Kumar, S.; Agarwal, G.S.; Rai, G.P. Evaluation of PCR, DNA hybridization and immunomagnetic separation - PCR for detection of Burkholderia mallei in artificially inoculated environmental samples. Indian J Microbiol 2010, 50, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, H.; Atherton, J.G.; Simpson, D.J.; Taylor, C.E.; Rosenthal, R.O.; Brown, D.F.; Wreghitt, T.G. Genital infection in mares. The Veterinary record 1977, 101, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atherton, J.G. Isolation of CEM organism. Vet Rec 1978, 102, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.S.; Donahue, J.M.; Arata, A.B.; Goris, J.; Hansen, L.M.; Earley, D.L.; Vandamme, P.A.; Timoney, P.J.; Hirsh, D.C. Taylorella asinigenitalis sp. nov., a bacterium isolated from the genital tract of male donkeys (Equus asinus). International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2001, 51, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.; Bugg, M.; Robinson, C.; Mitchell, Z.; Davis-Poynter, N.; Newton, J.R.; Jolley, K.A.; Maiden, M.C.J.; Waller, A.S. Sequence Variation of the SeM Gene of Streptococcus equi Allows Discrimination of the Source of Strangles Outbreaks. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2006, 44, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, F.M.; Newton, J.R. A practitioner's guide to understanding infectious disease diagnostics in the United Kingdom. Part 2: Serological diagnostic testing methods and diagnostic test result interpretation. Equine Veterinary Education 2022, 34, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, K.L.; Crisman, M.V. Diagnostic Equine Serology. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice 2008, 24, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Premanandh, J.; George, L.V.; Wernery, U.; Sasse, J. Evaluation of a newly developed real-time PCR for the detection of Taylorella equigenitalis and discrimination from T. asinigenitalis. Veterinary Microbiology 2003, 95, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.; Steward, K.F.; Potts, N.; Barker, C.; Hammond, T.A.; Pierce, K.; Gunnarsson, E.; Svansson, V.; Slater, J.; Newton, J.R.; et al. Combining two serological assays optimises sensitivity and specificity for the identification of Streptococcus equi subsp. equi exposure. Vet J 2013, 197, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, V.; Kumar, S.; Malik, P.; Rai, G.P. Evaluation of recombinant proteins of Burkholderia mallei for serodiagnosis of glanders. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012, 19, 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellon, D.C.; Besser, T.E.; Vivrette, S.L.; McConnico, R.S. Comparison of Nucleic Acid Amplification, Serology, and Microbiologic Culture for Diagnosis of Rhodococcus equi Pneumonia in Foals. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2001, 39, 1289–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J. From glanders to Hendra virus: 125 years of equine infectious diseases. The Veterinary Record 2013, 173, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, A.G.; Stefanovski, D.; Rankin, S.C. Comparison of nasopharyngeal and guttural pouch specimens to determine the optimal sampling site to detect Streptococcus equi subsp equi carriers by DNA amplification. BMC Vet Res 2017, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, M.; Sannarangaiah, S.; Dash, P.K.; Rao, P.V.; Morita, K. Loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): a new generation of innovative gene amplification technique; perspectives in clinical diagnosis of infectious diseases. Rev Med Virol 2008, 18, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, S.; Riedel, T.E.; Saldaña, M.A.; Hegde, S.; Pederson, N.; Hughes, G.L.; Ellington, A.D. Direct nucleic acid analysis of mosquitoes for high fidelity species identification and detection of Wolbachia using a cellphone. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018, 12, e0006671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, T.E.; Zimmer-Faust, A.G.; Thulsiraj, V.; Madi, T.; Hanley, K.T.; Ebentier, D.L.; Byappanahalli, M.; Layton, B.; Raith, M.; Boehm, A.B.; et al. Detection limits and cost comparisons of human- and gull-associated conventional and quantitative PCR assays in artificial and environmental waters. Journal of Environmental Management 2014, 136, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notomi, T.; Mori, Y.; Tomita, N.; Kanda, H. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): principle, features, and future prospects. Journal of Microbiology 2015, 53, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, H.; Kawana, T.; Fukushima, E.; Suzutani, T. Tolerance of loop-mediated isothermal amplification to a culture medium and biological substances. J Biochem Biophys Methods 2007, 70, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, J.; Chauhan, K.; Hwang, S.H.; Jeong, Y.J.; Kim, D.E. Enhanced Specificity in Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification with Poly(ethylene glycol)-Engrafted Graphene Oxide for Detection of Viral Genes. Biosensors (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, Y.; Niwa, H.; Katayama, Y.; Hariu, K. Development of loop-mediated isothermal amplification methods for detecting Taylorella equigenitalis and Taylorella asinigenitalis. J Equine Sci 2015, 26, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzai, S.; Safi, S.; Mossavari, N.; Afshar, D.; Bolourchian, M. Development of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid detection of Burkholderia mallei. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2016, 62, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hobo, S.; Niwa, H.; Oku, K. Development and Application of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Methods Targeting the seM Gene for Detection of Streptococcus equi subsp. equi. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2012, 74, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North, S.E.; Das, P.; Wakeley, P.; Sawyer, J. Development of a rapid isothermal assay to detect the causative agent of strangles. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 2012, 32, S54–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, Y.; Kakoi, H.; Ishige, T.; Yamanaka, T.; Niwa, H.; Uchida-Fujii, E.; Nukada, T.; Ueno, T. Comparison of seven nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Taylorella equigenitalis. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2022, 84, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-C.; Peng, J.; Mauk, M.G.; Awasthi, S.; Song, J.; Friedman, H.; Bau, H.H.; Liu, C. Smart cup: A minimally-instrumented, smartphone-based point-of-care molecular diagnostic device. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2016, 229, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.; Kim, S. Inhibition of Non-specific Amplification in Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification via Tetramethylammonium Chloride. Biochip J 2022, 16, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.-B.; Yin, G.-Y.; Zhao, G.-P.; Huang, A.-H.; Wang, J.-H.; Yang, S.-F.; Gao, H.-S.; Kang, W.-J. Development of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) for Universal Detection of Enteroviruses. Indian Journal of Microbiology 2014, 54, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.T. Empirical aspects of strand displacement amplification. PCR Methods Appl 1993, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendrakumar, C.S.V.; Suryanarayana, T.; Reddy, A.R. DNA helix destabilization by proline and betaine: possible role in the salinity tolerance process. FEBS Letters 1997, 410, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyan, D.-C.; Ulitzky, L.E.; Cehan, N.; Williamson, P.; Winkelman, V.; Rios, M.; Taylor, D.R. Rapid Detection of Hepatitis B Virus in Blood Plasma by a Specific and Sensitive Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2014, 59, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, K.A.; Rudolph, D.L.; Morrison, D.; Guelig, D.; Diesburg, S.; McAdams, D.; Burton, R.A.; LaBarre, P.; Owen, M. Single-use, electricity-free amplification device for detection of HIV-1. Journal of Virological Methods 2016, 237, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-W.; Ching, W.-M. Evaluation of the stability of lyophilized loop-mediated isothermal amplification reagents for the detection of Coxiella burnetii. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.; Akrami, K.; Hall, D.; Smith, D.; Aronoff-Spencer, E. Lyophilized visually readable loop-mediated isothermal reverse transcriptase nucleic acid amplification test for detection Ebola Zaire RNA. Journal of Virological Methods 2017, 244, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Guo, J.; Lu, Z.; Bie, X.; Lv, F.; Zhao, H. Development of a test kit for visual loop-mediated isothermal amplification of Salmonella in spiked ready-to-eat fruits and vegetables. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2020, 169, 105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, E.; Wee, E.; Wang, Y.; Trau, M. Comprehensive evaluation of molecular enhancers of the isothermal exponential amplification reaction. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 37837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hédoux, A.; Willart, J.-F.; Paccou, L.; Guinet, Y.; Affouard, F.; Lerbret, A.; Descamps, M. Thermostabilization Mechanism of Bovine Serum Albumin by Trehalose. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2009, 113, 6119–6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, W.A.; Yager, T.D.; Korte, J.; Von Hippel, P.H. Betaine can eliminate the base pair composition dependence of DNA melting. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, H.-Y.; Shoemaker, C.A.; Klesius, P.H. Evaluation of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for rapid detection of channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus important bacterial pathogen Edwardsiella ictaluri. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2005, 63, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Shi, C. Accelerated isothermal nucleic acid amplification in betaine-free reaction. Analytical Biochemistry 2017, 530, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Guo, J.; Xu, L.; Gao, S.; Lin, Q.; Wu, Q.; Wu, L.; Que, Y. Establishment and application of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) system for detection of cry1Ac transgenic sugarcane. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 4912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, F.; Beaulieu, J.C.; Stein, R.E.; Ge, B. Rapid detection of viable salmonellae in produce by coupling propidium monoazide with loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011, 77, 4008–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ren, G.; Buss, J.; Barry, A.J.; Patton, G.C.; Tanner, N.A. Enhancing colorimetric loop-mediated isothermal amplification speed and sensitivity with guanidine chloride. BioTechniques 2020, 69, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, O.E.; Holtkamp, C.; Schäfer, M.; Schön, F.; Eis-Hübinger, A.M.; Krumbholz, A. Fast Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA Directly from Respiratory Samples Using a Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Test. Viruses 2021, 13, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewadikaram, M.; Perera, K.; Dissanayake, K.; Ramanayake, M.; Isurika, S.C.; Panch, A.; Jayarathne, A.; Pushpakumara, P.; Malavige, N.; Jeewandara, C.; et al. Development of Duplex and Multiplex Reverse Transcription Loop Mediated Isothermal Amplification (RT-LAMP) Assays for Clinical Diagnosis of SARS-COV-2 in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2022, 116, S39–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Huang, S.; Liu, N.; Dong, D.; Yang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Ma, W.; He, X.; Ao, D.; Xu, Y.; et al. Establishment of an accurate and fast detection method using molecular beacons in loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 40125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Wu, J.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Ji, F. On-point detection of GM rice in 20 minutes with pullulan as CPA acceleration additive. Analytical Methods 2014, 6, 9198–9201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Hui, C.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, J.; Kannan, B.; Jahanshahi-Anbuhi, S.; Filipe, C.D.M.; Brennan, J.D.; Li, Y. Target-Induced and Equipment-Free DNA Amplification with a Simple Paper Device. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2016, 55, 2709–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Sun, B.; Guan, Y. Pullulan reduces the non-specific amplification of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2019, 411, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, R.; Schutt, C.E. The enhancement of PCR amplification by low molecular-weight sulfones. Gene 2001, 274, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.A.; Fukushima, M.; Davis, R.W. DMSO and betaine greatly improve amplification of GC-rich constructs in de novo synthesis. PLoS One 2010, 5, e11024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.-G.; Brewster, J.D.; Paul, M.; Tomasula, P.M. Two Methods for Increased Specificity and Sensitivity in Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification. Molecules 2015, 20, 6048–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Maestu, A.; Fuciños, P.; Azinheiro, S.; Carvalho, J.; Prado, M. Systematic loop-mediated isothermal amplification assays for rapid detection and characterization of Salmonella spp., Enteritidis and Typhimurium in food samples. Food Control 2017, 80, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Maestu, A.; Azinheiro, S.; Fuciños, P.; Carvalho, J.; Prado, M. Highly sensitive detection of gluten-containing cereals in food samples by real-time Loop-mediated isothermal AMPlification (qLAMP) and real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Food Chemistry 2018, 246, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbazi, E.; Mollasalehi, H.; Minai-Tehrani, D. Development and evaluation of an improved quantitative loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for rapid detection of Morganella morganii. Talanta 2019, 191, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchior, W.B., Jr.; Von Hippel, P.H. Alteration of the relative stability of dA-dT and dG-dC base pairs in DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1973, 70, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roskos, K.; Hickerson, A.I.; Lu, H.W.; Ferguson, T.M.; Shinde, D.N.; Klaue, Y.; Niemz, A. Simple system for isothermal DNA amplification coupled to lateral flow detection. PLoS One 2013, 8, e69355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, N.; Fukuda, T.; Nonen, S.; Hashimoto, K.; Azuma, J.; Gemma, N. Simple and accurate determination of CYP2D6 gene copy number by a loop-mediated isothermal amplification method and an electrochemical DNA chip. Clinica Chimica Acta 2010, 411, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denschlag, C.; Vogel, R.F.; Niessen, L. Hyd5 gene based analysis of cereals and malt for gushing-inducing Fusarium spp. by real-time LAMP using fluorescence and turbidity measurements. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2013, 162, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, C.A.L.; Kubo, T.; Grobbelaar, A.A.; Vuren, P.J.v.; Weyer, J.; Nel, L.H.; Swanepoel, R.; Morita, K.; Paweska, J.T. Development and Evaluation of a Real-Time Reverse Transcription-Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay for Rapid Detection of Rift Valley Fever Virus in Clinical Specimens. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2009, 47, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, T.-L.; Wei, S.-C.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lin, C.-W. A polycarbonate based surface plasmon resonance sensing cartridge for high sensitivity HBV loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2012, 32, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, N.; Mori, Y.; Kanda, H.; Notomi, T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of gene sequences and simple visual detection of products. Nature Protocols 2008, 3, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diribe, O.; Fitzpatrick, N.; Sawyer, J.; La Ragione, R.; North, S. A Rapid and Simple Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay for the Detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa From Equine Genital Swabs. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 2015, 35, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diribe, O.; North, S.; Sawyer, J.; Roberts, L.; Fitzpatrick, N.; La Ragione, R. Design and application of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for the rapid detection of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 2014, 26, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, R.L.; Reed, D.E.; Hubbard, M.A.; Dillon, M.J.; Chen, H.; Currie, B.J.; Mayo, M.; Sarovich, D.S.; Theobald, V.; Limmathurotsakul, D.; et al. Development of a prototype lateral flow immunoassay (LFI) for the rapid diagnosis of melioidosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014, 8, e2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroenram, W.; Kiatpathomchai, W.; Flegel, T.W. Rapid and sensitive detection of white spot syndrome virus by loop-mediated isothermal amplification combined with a lateral flow dipstick. Molecular and Cellular Probes 2009, 23, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Teng, D.; Guan, Q.; Tian, F.; Wang, J. Detection of Roundup Ready soybean by loop-mediated isothermal amplification combined with a lateral-flow dipstick. Food Control 2013, 29, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdry, V.K.; Luo, Y.; Widén, F.; Qiu, H.-J.; Shan, H.; Belák, S.; Liu, L. Development of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay combined with a lateral flow dipstick for rapid and simple detection of classical swine fever virus in the field. Journal of Virological Methods 2014, 197, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauk, M.G.; Song, J.; Liu, C.; Bau, H.H. Simple Approaches to Minimally-Instrumented, Microfluidic-Based Point-of-Care Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests. Biosensors 2018, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Causative agent | Disease | Gold standard technique* Common detection method |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhodococcus equi | Pneumonia | Bacterial isolation (culture)* PCR1 |

[62] |

| Streptococcus equi subsp. equi | Strangles | qPCR2* Bacterial isolation (culture) ELISA3 |

[95] |

| Taylorella equingenitalis | Contagious equine metritis (CEM) | Bacterial isolation (culture)* IFAT4 Real-time PCR |

[109] |

| Burkholderia mallei | Glanders | CFT5* Bacterial isolation (culture) ELISA PCR |

[126] |

| Disease | Target gene | Sample | Monitoring | Analytical sensitivity |

Clinical sensitivity | Specificity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contagious equine metritis | 23s rRNA | Culture isolate, Genital swabs1 |

Turbidity | 24.8 copies/rxn |

71% | 100% | [161] |

| Glanders | Integrase | Culture isolate, Clinical isolate |

Turbidity | 22 ng/µl | NA | 100% | [162] |

| BMA10229_375 | Culture isolate, Blood1 |

Turbidity | 1 pg/rxn | NA | 100% | [45] | |

| Flip-IS40JA | Culture isolate, Blood1 |

Turbidity | 0.25 pg/rxn | NA | 100% | [12] | |

| Pneumonia (Rhodococcus equi) | vapA | Clinical sample (TW)2 |

Turbidity | 10 CFU/rxn | 91.4% | 93.8% | [43] |

| Strangles | seM | Clinical sample (NW)3 |

Turbidity | 0.1 CFU/rxn | NA | 100% | [163] |

| eqbE | Clinical samples (NP FS4, NPW5, GPL6) |

Fluorescence | 1 CFU/rxn | 77% | 78% | [154,164] | |

| eqbE | Clinical samples (GPL) |

Microfluidic device | 1 CFU/rxn | 100% | 62% | [44] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).