Submitted:

28 June 2023

Posted:

29 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Impact of Teleworking

- Individual

- Organizational

- Social

1.2. Challenges to the implementation of telework

- Environmental: the economic uncertainty that accompanies the health crisis is a stressful factor, due to the fear of losing a job. Simultaneously, a technological change is taking place.

- Organizational: with the assumption of responsibilities, the work role of teleworkers is overloaded, while there is a lack of social support, space problems and distraction.

- Personal: this is the case of conflict of family-professional responsibilities.

- Physiological: e.g. headaches, high blood pressure, chronic diseases.

- Psychological: eg job dissatisfaction, depression, uncertainty about future prospects due to pandemic, insufficient conditions for well-being.

- Behavioral: e.g. nervousness, absenteeism.

- Exit.

- Voice.

- Loyalty.

- Neglect.

- Decreased productivity: as a result of low performance and deviant behavior at work due to lack of job satisfaction.

- Low degree of internal business communication/cooperation: given the work inclusion experienced in teleworking conditions, there is a high possibility of misunderstandings within the company and time delays.

- Poor services/products quality: as a consequence of the above problems such as low morale and the increase in the number of errors, the project provided may not meet the specifications of the company [98].

- Training: training in the form of seminars can help support and improve self-efficacy.

- Employee involvement: the employee must be involved in matters related to his/her job performance (eg making decisions or submitting proposals for improvements).

- Organizational communication: due to the isolation of the individual it would be useful to increase the formal organizational communication in order to properly manage issues and reduce stress.

- Leave and wellness programs: for exhausted employees, it is important to take leave for their rejuvenation and to have access to psychological support programs.

1.3. Telework and Sustainable Development

- No 3. Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages;

- No 4. Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all;

- No 5. Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls;

- No 8. Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all;

- No 9. Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and foster innovation;

- No 10. Reduce inequality within and among countries;

- No 11. Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable;

- No 12. Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns;

- No 13. Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

1.4. Telework and the frame for sustainable behaviors

- No 1. End poverty in all its forms everywhere;

- No 2. End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture;

- No 6. Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all;

- No 7. Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all;

- No 14. Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development;

- No 15. Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss;

- No 16. Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels;

- No 17. Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development.

1.5. The role of leaders on remote work

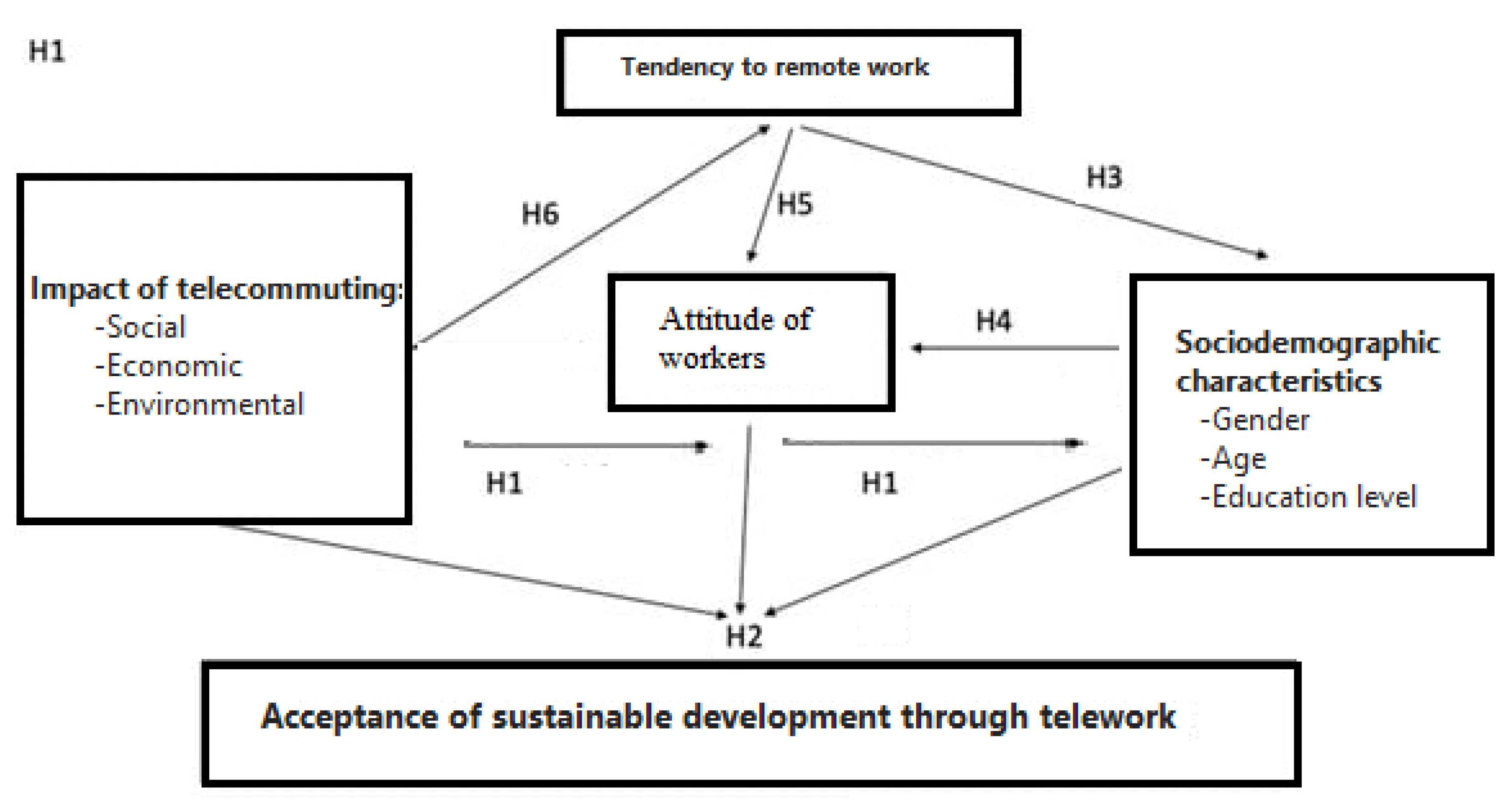

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

| Part 1: The individual/teleworkers’ perspectives | |

| + Autonomy / independence [22]. + Flexible working hours [22][19][67]. +Improving time management, professional flexibility [22]. +Saving time and travel expenses [22][26][84]. +Flexibility in organizing care for family members/relatives [22][40][20][73]. + Job satisfaction [38][8][69]. + Personalised workspace and chosen silence: it concerns workers with their own workplace, which promotes well-being, concentration and few distractions. It allows you to work from anywhere [12][42]. + Reduced stress from arriving late for work - Less travel time will reduce travel stress [20][74][40]. + Teleworkers were able to develop greater social support relationships with certain colleagues, especially other teleworkers, while simultaneously allowing them to distance themselves from negative work relationships [104]. |

- Reduced sense of belonging [22]. - Professional and social isolation, lack of face to face, in person interactions and emotional support from colleagues, negative effects on co-worker relationships, less visibility, observation [22][31][42][14][79]. - Hyperavailability Syndrome- Work-life imbalance - Employees struggle to separate work and home life[22][76][40][31]. - Need for self-discipline & motivation [22][31]. - Lack of professional support [22][80]. - Performance Control, loss of data security and equipment accountability [31][25]. -The increased use of electronic monitoring and surveillance methods by employers can increase employee anxiety and stress levels and increase the invasion of teleworkers' privacy [42][107][23]. - Legal issues, loss of legal rights (e.g. teleworkers' right to log off, unpaid overtime hours [2][45]. - Reduced employment opportunities - Teleworking negatively affects career aspirations due to inadequate managerial assessments [22][67][74][75]. - Lack of skills - Inadequate training [40][84]. - Technostress, digital exhaust, technology dependence and sedentary life as impacts on workers' mental and physical health and safety [42],[49][9][39]. - Long working hours and a lack of adequate work space and ergonomically adapted equipment and furniture at home can also increase risks to teleworkers' physical health [42],[49][9]. |

| Part 2: The organizational perspectives | |

| + Increase in productivity [22][31][78]. + Secure retention, strengthen organizational commitment and improve performance within the organization [78]. + Increased supply of human resources [22][31]. + Significant reduction in absenteeism and delays [22][31]. + Savings on direct costs [22][31]. + Increased motivation and satisfaction [22][72]. + Creation of a positive corporate image [22]. + Reductions in office space requirements, capital + Retention of rare skills and talents [31][72]. |

- Implementation difficulties for centrally managed organizations [22][72]. - Investments in training and new methods of supervision [22][72]. - Challenges for managers [22][72]. - Potential damage to engagement and identification with the organization due to complex communication [22][72]. - Changes in working methods [22][72]. - Costs associated with moving to teleworking [22]. - Legal issues [22][31]. - Internal HR Policies - If these policies are not designed and implemented, employees will only depend on the management support [24][38]. - Difficulties in selecting suitable work activities and people. -Teleworking may apply to some employees [22][20][73]. - Loss of data security and equipment accountability [31]. |

| Part 3: The societal & SDG perspectives | |

| + Reduction of environmental damage[22][31][106][41]. + Reduce traffic/congestion [22][31][106][41]. + Solutions for population groups with special needs or health problems [22]. + Reduces discrimination (i.g. gender, sexual orientation, religion, skin color or nationality). Perceived discrimination may be reduced since telecommuting, by definition, reduces physical, face-to-face interaction [44][36][74]. + Saving of infrastructure and energy [31][106][41]. +Regeneration for rural or marginal areas. Through Internet access and the trend of digital nomads, a town could get an economic boost [62][42][10]. +Benefits for the family. Parents can prioritize family and have more time for their children or themselves [20][23][73][40]. +Health living (i.e. lessens fast food consumption) [37][54]. +Telecommuting appears to be a community-friendly form of work, because telecommuters tend to report involvement in both volunteer and political/union activities [34]. +Benefits the military spouse population, which is an underutilized and underemployed group of educated or experienced professionals. Due to their frequent movements and need for flexibility, many remain unemployed [31][16]. +Extends career beyond retirement. It also allows retirees to maintain their savings while remaining professionally and physical active in giving back to their communities and families [67][40]. +Improves Public Health as it can help keep people healthy (e.g. during Covid-19) [8][49]. |

-Social distancing [22]. -The existence of socio-cultural barriers (e.g. particularly in autocraticasian societies) may hinder the utilization of the benefits of teleworking [25]. -Home energy consumption patterns may offset the benefits of teleworking[45,6][42][47]. -Dependency on technology [42]. -Effects on the mental and physical health and safety of workers may have an impact on society [42][25][50][45]. - Women who telecommute from home also face increased risks of digital harassment and domestic violence [42]. - Degradation of labor rights [45]. - It can lead to further urban sprawl and gentrification that would undermine environmental benefits. [45]. - Fragmentation of the workforce, individualization of employment relationships and the emergence of new inequalities in the labor market between those who can work remotely and those who cannot (e.g. because not everyone has access to broadband or the necessary equipment and space at home). These inequalities are closely related to socio-economic inequalities [42]. |

2.1. Individual / Teleworkers’ perspectives on telecommuting

2.2. Organizational perspective of telework

2.3. Societal & SDG perspectives of telework

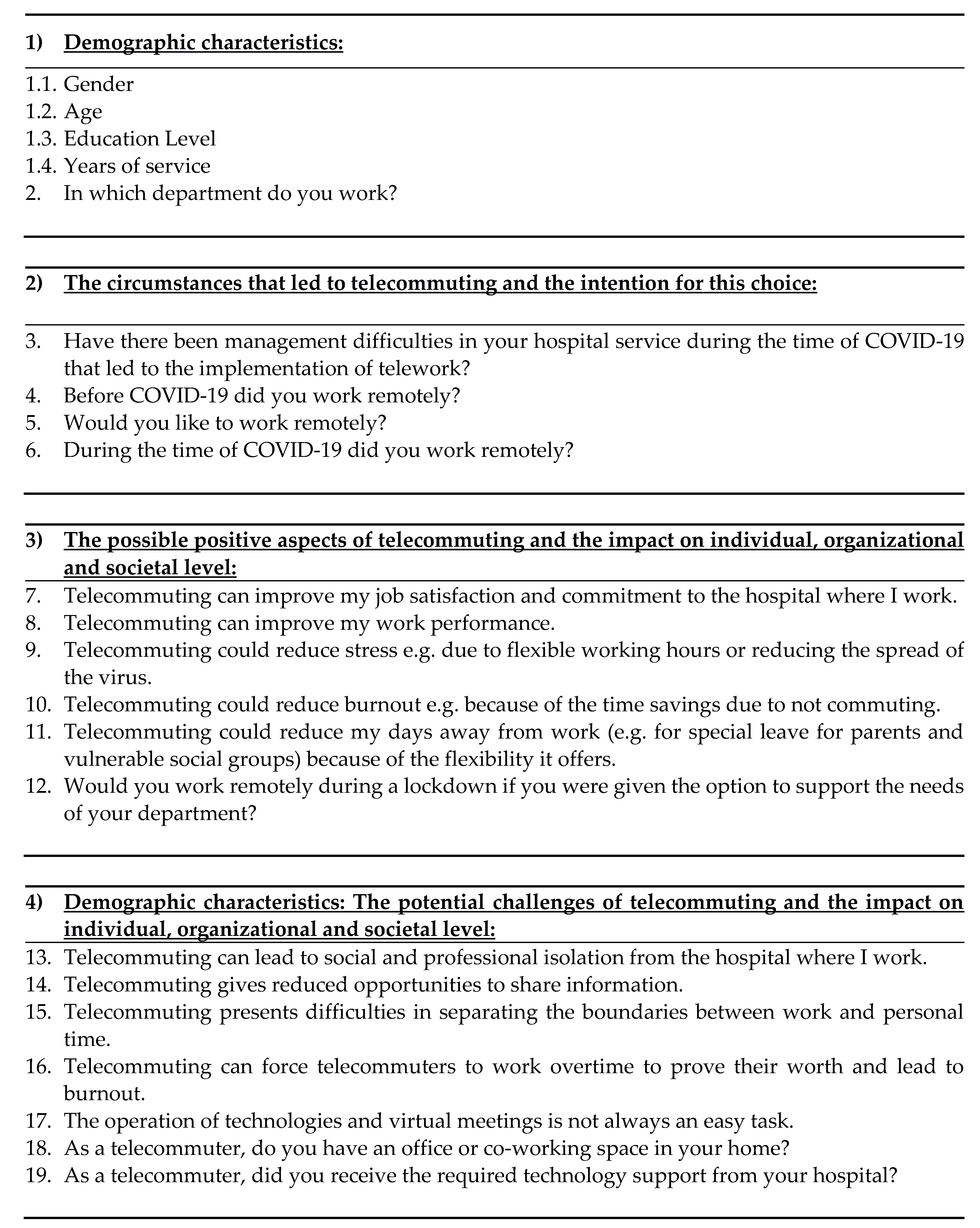

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Questions

3.2. Research Tool and Data Collection

3.3. Sampling and Participants

4. Results

4.1. Results of Descriptive Statistics

4.1.1. Demographic characteristics

| Distribution of answers regarding the sample (N=125): | ||||

| 1.1. Gender | ||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | |

| Female | 109 | 87.2 | 87.2 | 87.2 |

| Male | 16 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 100 |

| Total | 125 | 100 | 100 | |

| 1.2. Age | ||||

| 18-24 | 2 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| 25-30 | 8 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 8 |

| 31-40 | 14 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 19.2 |

| 41-55 | 94 | 75.2 | 75.2 | 94.4 |

| 55+ | 7 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 100 |

| Total | 125 | 100 | 100 | |

| 1.3. Education Level | ||||

| Secondary education | 24 | 19.2 | 19.2 | 19.2 |

| Higher education | 54 | 43.2 | 43.2 | 62.4 |

| Master's degree holder | 42 | 33.6 | 33.6 | 96 |

| Holder of a Ph.D | 5 | 4 | 4 | 100 |

| Total | 125 | 100 | 100 | |

| 1.4.Years of service: Median=17.00 . Interquartile Range: 11.00 | ||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | |

| Citizen service office | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Call center | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.6 |

| Surgery warehouse | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 2.4 |

| Secretariat | 40 | 32 | 32 | 34.4 |

| Office of Education | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 35.2 |

| Program management office | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 36 |

| Patient movement office | 5 | 4 | 4 | 40 |

| Supply office | 3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 42.4 |

| Telemedicine design and development office | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 43.2 |

| Dietetics department | 2 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 44.8 |

| Human resources management | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 45.6 |

| Material Management Department | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 46.4 |

| Hospital director | 3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 48.8 |

| Quality control department | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 49.6 |

| Medical service | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 50.4 |

| Social service | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 51.2 |

| Accounting department | 30 | 24 | 24 | 75.2 |

| Payroll | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 76 |

| Nursing department | 2 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 77.6 |

| Economics Department | 4 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 80.8 |

| Pathological clinic | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 81.6 |

| Order Office | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 82.4 |

| Nursing service | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 83.2 |

| Department of receipt of sanitary material | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 84 |

| Information technology department | 6 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 88.8 |

| Protocol Department | 2 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 90.4 |

| Human ressources Department | 8 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 96.8 |

| Quality control service | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 97.6 |

| Pharmacy | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 98.4 |

| Psychiatric clinic | 2 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 100 |

| Total | 125 | 100 | 100 |

4.1.2. Descriptions for the main research part

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | |

| I absolutely disagree | 2 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Disagree | 3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 4 |

| I neither agree nor disagree | 18 | 14.4 | 14.4 | 18.4 |

| Agree | 50 | 40 | 40 | 58.4 |

| Strongly Agree | 52 | 41.6 | 41.6 | 100 |

| Total | 125 | 100 | 100 | |

| Median=4 . Interquartile Range=1 | ||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| No | 109 | 87.2 | 87.2 | 87.2 | |

| yes | 16 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Νο | 47 | 37.6 | 37.6 | 37.6 | |

| Yes | 78 | 62.4 | 62.4 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Νο | 44 | 35.2 | 35.2 | 35.2 | |

| Yes | 81 | 64.8 | 64.8 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| I absolutely disagree | 13 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 10.4 | |

| Disagree | 14 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 21.6 | |

| I neither agree nor disagree | 43 | 34.4 | 34.4 | 56.0 | |

| Agree | 32 | 25.6 | 25.6 | 81.6 | |

| Strongly Agree | 23 | 18.4 | 18.4 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Median=3.Interquartile Range=4 | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| I absolutely disagree | 14 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 11.2 | |

| Disagree | 22 | 17.6 | 17.6 | 28.8 | |

| I neither agree nor disagree | 34 | 27.2 | 27.2 | 56.0 | |

| Agree | 29 | 23.2 | 23.2 | 79.2 | |

| Strongly Agree | 26 | 20.8 | 20.8 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Median=3.Interquartile Range=2 | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| I absolutely disagree | 4 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 | |

| Disagree | 5 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 7.2 | |

| I neither agree nor disagree | 28 | 22.4 | 22.4 | 29.6 | |

| Agree | 45 | 36.0 | 36.0 | 65.6 | |

| Strongly Agree | 43 | 34.4 | 34.4 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Median=4.Interquartile Range=2 | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | I absolutely disagree | 4 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Disagree | 12 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 12.8 | |

| I neither agree nor disagree | 17 | 13.6 | 13.6 | 26.4 | |

| Agree | 47 | 37.6 | 37.6 | 64.0 | |

| Strongly Agree | 45 | 36.0 | 36.0 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Median=4.Interquartile Range=2 | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| I absolutely disagree | 6 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.8 | |

| Disagree | 6 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 9.6 | |

| I neither agree nor disagree | 19 | 15.2 | 15.2 | 24.8 | |

| Agree | 46 | 36.8 | 36.8 | 61.6 | |

| Strongly Agree | 48 | 38.4 | 38.4 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Median=4.Interquartile Range=2 | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Νο | 6 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.8 | |

| Yes | 119 | 95.2 | 95.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| I absolutely disagree | 3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | |

| Disagree | 16 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 15.2 | |

| I neither agree nor disagree | 43 | 34.4 | 34.4 | 49.6 | |

| Agree | 33 | 26.4 | 26.4 | 76.0 | |

| Strongly Agree | 30 | 24.0 | 24.0 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Median=4.Interquartile Range=1 | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| I absolutely disagree | 5 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | |

| Disagree | 17 | 13.6 | 13.6 | 17.6 | |

| I neither agree nor disagree | 34 | 27.2 | 27.2 | 44.8 | |

| Agree | 46 | 36.8 | 36.8 | 81.6 | |

| Strongly Agree | 23 | 18.4 | 18.4 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Median=4.Interquartile Range=1 | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| I absolutely disagree | 4 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 | |

| Disagree | 12 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 12.8 | |

| I neither agree nor disagree | 28 | 22.4 | 22.4 | 35.2 | |

| Agree | 39 | 31.2 | 31.2 | 66.4 | |

| Strongly Agree | 42 | 33.6 | 33.6 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Median=4.Interquartile Range=2 | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| I absolutely disagree | 10 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | |

| Disagree | 20 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 24.0 | |

| I neither agree nor disagree | 31 | 24.8 | 24.8 | 48.8 | |

| Agree | 34 | 27.2 | 27.2 | 76.0 | |

| Strongly Agree | 30 | 24.0 | 24.0 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Median=4.Interquartile Range=1 | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| I absolutely disagree | 4 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 | |

| Disagree | 12 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 12.8 | |

| I neither agree nor disagree | 35 | 28.0 | 28.0 | 40.8 | |

| Agree | 48 | 38.4 | 38.4 | 79.2 | |

| Strongly Agree | 26 | 20.8 | 20.8 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Median=4.Interquartile Range=1 | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Νο | 51 | 40.8 | 40.8 | 40.8 | |

| Yes | 74 | 59.2 | 59.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Νο | 96 | 76.8 | 76.8 | 76.8 |

| Yes | 29 | 23.2 | 23.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

4.2. Results of Inductive Statistics

4.2.1. Relationship between main research part questions and age

| Questions | Age | N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks |

| 1) Have there been management difficulties in your hospital service during the time of COVID-19 that led to the implementation of telework? | <41 years old | 24 | 44.85 | 1076.50 |

| 41 years and older | 101 | 67.31 | 6798.50 | |

| U=776.5 P=0.003 | ||||

| 2) Telecommuting can improve my job satisfaction and commitment to the hospital where I work. | <41 years old | 24 | 67.65 | 1623.50 |

| 41 years and older | 101 | 61.90 | 6251.50 | |

| U=1100.5 P=0.47 | ||||

| 3) Telecommuting can improve my work performance. | <41 years old | 24 | 69.92 | 1678.00 |

| 41 years and older | 101 | 61.36 | 6197.00 | |

| U=1046.0 P=0.286 | ||||

| 4) Telecommuting could reduce stress e.g. due to flexible working hours or reducing the spread of the virus. | <41 years old | 24 | 69.48 | 1667.50 |

| 41 years and older | 101 | 61.46 | 6207.50 | |

| U=1056.5 P=0.305 | ||||

| 5) Telecommuting could reduce burnout e.g. because of the time savings due to not commuting. | <41 years old | 24 | 69.52 | 1668.50 |

| 41 years and older | 101 | 61.45 | 6206.50 | |

| U=1055.5 P=0.300 | ||||

| 6) Telecommuting could reduce my days away from work because of the flexibility it offers. | <41 years old | 24 | 58.04 | 1393.00 |

| 41 years and older | 101 | 64.18 | 6482.00 | |

| U=1093.0 P=0.429 | ||||

| 7) Telecommuting can lead to social and professional isolation from the hospital where I work. | <41 years old | 24 | 63.40 | 1521.50 |

| 41 years and older | 101 | 62.91 | 6353.50 | |

| U=1202.5 P=0.951 | ||||

| 8)Telecommutinggives reduced opportunities to share information. | <41 years old | 24 | 60.08 | 1442.00 |

| 41 years and older | 101 | 63.69 | 6433.00 | |

| U=1142.0 P=0.648 | ||||

| 9) Telecommuting presents difficulties in separating the boundaries between work and personal time. | <41 years old | 24 | 61.31 | 1471.50 |

| 41 years and older | 101 | 63.40 | 6403.50 | |

| U=1171.5 P=0.791 | ||||

| 10) Telecommuting can force telecommuters to work overtime to prove their worth and lead to burnout. | <41 years old | 24 | 53.46 | 1283.00 |

| 41 years and older | 101 | 65.27 | 6592.00 | |

| U=983.0 P=0.140 | ||||

| 11) The operation of technologies and virtual meetings is not always an easy task | <41 years old | 24 | 59.75 | 1434.00 |

| 41 years and older | 101 | 63.77 | 6441.00 | |

| U=1134.0 P=0.609 | ||||

| Variables | Categories | Age | x2 (1) | p | |

| <41 years old | 41+ years old | ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| 1) Before COVID-19. did you work remotely? | Νο | 19 | 90 | 1.72 | 0.190 |

| 79.2% | 89.1% | ||||

| Yes | 5 | 11 | |||

| 20.8% | 10.9% | ||||

| 2) Would you like to work remotely? | Νο | 7 | 40 | 0.90 | 0.343 |

| 29.2% | 39.6% | ||||

| Yes | 17 | 61 | |||

| 70.8% | 60.4% | ||||

| 3) During the time of COVID-19. did you work remotely? | Νο | 8 | 36 | 0.045 | 0.831 |

| 33.3% | 35.6% | ||||

| Yes | 16 | 65 | |||

| 66.7% | 64.4% | ||||

| 4) As a telecommuter. do you have an office or co-working space in your home? | Νο | 10 | 41 | 0.009 | 0.923 |

| 41.7% | 40.6% | ||||

| Yes | 14 | 60 | |||

| 58.3% | 59.4% | ||||

| 5) As a telecommuter. did you receive the required technology support from your hospital? | Νο | 21 | 75 | 1.909 | 0.167 |

| 87.5% | 74.3% | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 26 | |||

| 12.5% | 25.7% | ||||

4.2.2. Relationship between main research part questions and educational level

| Questions | Education level | N | Mean Rank |

| 1) Were there any management difficulties in your hospital service during the COVID-19 era that led to the implementation of telework? | Secondary education | 24 | 64.08 |

| Higher education | 54 | 54.05 | |

| Master's/PhD holder | 47 | 72.73 | |

| x2(2) = 7.796 p = 0.020 | |||

| 2) Telecommuting can improve my job satisfaction and commitment to the hospital where I work. | Secondary education | 24 | 49.31 |

| Higher education | 54 | 64.21 | |

| Master’s/PhD holder | 47 | 68.60 | |

| x2(2) = 4.934 p = 0.085 | |||

| 3) Telecommuting can improve my work performance. | Secondary education | 24 | 52.06 |

| Higher education | 54 | 64.16 | |

| Master’s/PhD holder | 47 | 67.26 | |

| x2(2) = 3.038 p = 0.219 | |||

| 4) Telecommuting could reduce stress e.g. due to flexible working hours or reducing the spread of the virus. | Secondary education | 24 | 60.10 |

| Higher education | 54 | 60.28 | |

| Master’s/PhD holder | 47 | 67.61 | |

| x2(2) = 1.351 p = 0.509 | |||

| 5) Telecommuting could reduce burnout e.g. because of the time savings due to not commuting. | Secondary education | 24 | 56.27 |

| Higher education | 54 | 63.56 | |

| Master’s/PhD holder | 47 | 65.79 | |

| x2(2) = 1.248 p = 0.536 | |||

| 6) Telecommuting could reduce my days away from work (e.g. for special leave for parents and vulnerable social groups) because of the flexibility it offers. | Secondary education | 24 | 57.44 |

| Higher education | 54 | 57.64 | |

| Master’s/PhD holder | 47 | 72.00 | |

| x2(2) = 5.224 p = 0.073 | |||

| 7) Telecommuting can lead to social and professional isolation from the hospital where I work. | Secondary education | 24 | 67.92 |

| Higher education | 54 | 65.36 | |

| Master’s/PhD holder | 47 | 57.78 | |

| x2(2) = 1.782 p = 0.410 | |||

| 8) Telecommutinggives reduced opportunities to share information. | Secondary education | 24 | 70.31 |

| Higher education | 54 | 62.61 | |

| Master’s/PhD holder | 47 | 59.71 | |

| x2(2) = 1.488 p = 0.475 | |||

| 9) Telecommuting presents difficulties in separating the boundaries between work and personal time. | Secondary education | 24 | 61.54 |

| Higher education | 54 | 65.47 | |

| Master’s/PhD holder | 47 | 60.90 | |

| x2(2) = 0.487 p = 0.784 | |||

| 10) Telecommuting can force telecommuters to work overtime to prove their worth and lead to burnout. | Secondary education | 24 | 60.38 |

| Higher education | 54 | 61.76 | |

| Master’s/PhD holder | 47 | 65.77 | |

| x2(2) = 0.490 p = 0.783 | |||

| 11) The operation of technologies and virtual meetings is not always an easy task. | Secondary education | 24 | 64.19 |

| Higher education | 54 | 66.73 | |

| Master’s/PhD holder | 47 | 58.11 | |

| x2(2) = 1.597 p = 0.450 | |||

| Education level | Mean Rank | U | P | |

| Have there been management difficulties in your hospital service …? | Secondary education | 43.54 | ||

| Higher education | 37.70 | |||

| 551.000 | 0.264 | |||

| Secondary education | 33.04 | |||

| Master’s/PhD holder | 37.51 | |||

| 493.000 | 0.341 | |||

| Higher education | 43.84 | |||

| Master’s/PhD holder | 59.22 | |||

| 882.500 | 0.004 |

- A statistically significant relationship is found between educational level and the variable "Would you like to work remotely?" (x2 (2) =8.46. p=0.015). In particular, the majority of participants who held a master's degree/doctorate (72.3%) wished to work remotely, as did the majority of participants who were graduates of higher education (64.8%). However, the majority of participants who were secondary school graduates did not wish to work remotely (62.5%).

- A statistically significant relationship is found between educational level and the variable "As teleworkers, did you receive the required technological support from your hospital?" (x2 (2) =10.01. p=0.007). In particular, the majority of participants who held a Master's/PhD (72.3%) stated that they had an office or friendly workspace at home. as did the majority of participants who were graduates of higher education (59.3%). However, the majority of participants who were secondary school graduates stated that they did not have an office or a friendly workspace at home (66.7%).

| Education level | ||||||

| Secondary education | Higher education | Master’s/PhD holder | ||||

| 1)Before COVID-19. did you work remotely? | Νο | Count | 20 | 49 | 40 | 109 |

| % within Education level | 83.3% | 90.7% | 85.1% | 87.2% | ||

| Yes | Count | 4 | 5 | 7 | 16 | |

| % within Education level | 16.7% | 9.3% | 14.9% | 12.8% | ||

| x2 (2) =1.113, p=0.573 | ||||||

| 2)Would you like to work remotely? | Νο | Count | 15 | 19 | 13 | 47 |

| % within Education level | 62.5% | 35.2% | 27.7% | 37.6% | ||

| Yes | Count | 9 | 35 | 34 | 78 | |

| % within Education level | 37.5% | 64.8% | 72.3% | 62.4% | ||

| x2 (2) =8.46, p=0.015) | ||||||

| 3)During the time of COVID-19. did you work remotely? | Νο | Count | 12 | 21 | 11 | 44 |

| % within Education level | 50.0% | 38.9% | 23.4% | 35.2% | ||

| Yes | Count | 12 | 33 | 36 | 81 | |

| % within Education level | 50.0% | 61.1% | 76.6% | 64.8% | ||

| x2 (2) =5.494.p=0.064 | ||||||

| 4)As a telecommuter. do you have an office or co-working space in your home? | Νο | Count | 16 | 22 | 13 | 51 |

| % within Education level | 66.7% | 40.7% | 27.7% | 40.8% | ||

| Yes | Count | 8 | 32 | 34 | 74 | |

| % within Education level | 33.3% | 59.3% | 72.3% | 59.2% | ||

| x2 (2) =10.01, p=0.007 | ||||||

| 5)As a telecommuter. did you receive the required technology support from your hospital? | Νο | Count | 22 | 39 | 35 | 96 |

| % within Education level | 91.7% | 72.2% | 74.5% | 76.8% | ||

| Yes | Count | 2 | 15 | 12 | 29 | |

| % within Education level | 8.3% | 27.8% | 25.5% | 23.2% | ||

| x2 (2) =3.756, p=0.153 | ||||||

5. Discussion

5.1. Recommendations for future research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albrecht SL, Bakker AB, Gruman JA, Macey WH, Saks AM. Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage: An integrated approach. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance. 2015 Mar 9.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B1%5D%09Albrecht+SL%2C+Bakker+AB%2C+Gruman+JA%2C+Macey+WH%2C+Saks+AM.+Employee+engagement%2C+human+resource+management+practices+and+competitive+advantage%3A+An+integrated+approach.+Journal+of+Organizational+Effectiveness%3A+People+and+Performance.+2015+Mar+9.&btnG= (accessed on 16 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Alipour JV, Falck O, Schüller S. Homeofficewährend der Pandemie und die ImplikationenfüreineZeitnach der Krise. ifoSchnelldienst. 2020;73(07):30-6. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B2%5D%09Alipour%2C+J.+V.%2C+Falck%2C+O.%2C+%26+Sch%C3%BCller%2C+S.+%282020%29.+Homeoffice+w%C3%A4hrend+der+Pandemie+und+die+Implikationen+f%C3%BCr+eine+Zeit+nach+der+Krise.+ifo+Schnelldienst%2C+73%2807%29%2C+30-36.&btnG=&https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/225150(accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Anderson N, Potočnik K, Zhou J. Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of management. 2014 Jul;40(5):1297-333. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B3%5D%09Anderson%2C+N.%2C+Poto%C4%8Dnik%2C+K.%2C+%26+Zhou%2C+J.+%282014%29.+Innovation+and+creativity+in+organizations%3A+A+state-of-the-science+review%2C+prospective+commentary%2C+and+guiding+framework.+Journal+of+management%2C+40%285%29%2C+1297-1333.+&btnG= (accessed on 16 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Baert S, Lippens L, Moens E, Weytjens J, Sterkens P. The COVID-19 crisis and telework: A research survey on experiences, expectations and hopes. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B4%5D%09Baert%2C+S.%2C+Lippens%2C+L.%2C+Moens%2C+E.%2C+Weytjens%2C+J.%2C+%26Sterkens%2C+P.+%282020%29.+The+COVID- (accessed on 17 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Balbontin C, Hensher DA, Beck MJ, Giesen R, Basnak P, Vallejo-Borda JA, Venter C. Impact of COVID-19 on the number of days working from home and commuting travel: A cross-cultural comparison between Australia, South America and South Africa. Journal of Transport Geography. 2021 Oct 1;96:103188. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B5%5D%09Balbontin%2C+C.%2C+Hensher%2C+D.+A.%2C+Beck%2C+M.+J.%2C+Giesen%2C+R.%2C+Basnak%2C+P.%2C+Vallejo-Borda%2C+J.+A.%2C+%26+Venter%2C+C.+%282021%29.+Impact+of+COVID-19+on+the+number+of+days+working+from+home+and+commuting+travel%3A+A+cross-cultural+comparison+between+Australia%2C+South+America+and+South+Africa.+Journal+of+Transport+Geography%2C+96%2C+103188&btnG= (accessed on 6 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Batut, C. and Tabet, Y., What do we know about the economic effects of remote work?, Direction générale du Trésor, Trésor-Economics, 2020. No. 270, November.Available at: https://www.tresor.economie.gouv.fr/Articles/7b3be9a0-7f07-4c7b-b5f9-85319aa7d02b/files/1527a501-7e52-4f7b-8dca-ba8a18f5a20d (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Beňo M. The advantages and disadvantages of E-working: An examination using an ALDINE analysis. Emerging Science Journal. 2021 Apr 19;5(1):11-20. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B7%5D%09Be%C5%88o%2C+M.+%282021%29.+The+advantages+and+disadvantages+of+E-working%3A+An+examination+using+an+ALDINE+analysis.+Emerging+Science+Journal%2C+5%281%29%2C+11-20.+&btnG=#d=gs_cit&t=1685464910686&u=%2Fscholar%3Fq%3Dinfo%3AqQxS9yEUICcJ%3Ascholar.google.com%2F%26output%3Dcite%26scirp%3D0%26hl%3Den(accessed on 18 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Bentley, T., McLeod, L. &Bosua, R. .Future of Work Program: The Trans-Tasman Telework Survey. 2013.AUT University. Available online: https://workresearch.aut.ac.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/34209/trans-tasman-telework-survey-report-Final-December-2013.pdf(accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Camacho, S., & Barrios, A. . Teleworking and technostress: early consequences of a COVID-19 lockdown. Cognition, Technology & Work, 2022. 24(3), 441-457. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B12%5D%09Camacho%2C+S.%2C+%26+Barrios%2C+A.+%282022%29.+Teleworking+and+technostress%3A+early+consequences+of+a+COVID-19+lockdown.+Cognition%2C+Technology+%26+Work%2C+24%283%29%2C+441-457&btnG= (accessed on 16 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Clark, M. A. . Teleworking in the countryside: Home-based working in the information society. Routledge2018. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B13%5D%09Clark%2C+M.+A.+%282018%29.+Teleworking+in+the+countryside%3A+Home-based+working+in+the+information+society.+Routledge&btnG= (accessed on 16 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Criscuolo, C., Gal, P., Leidecker, T., Losma, F., &Nicoletti, G. . The role of telework for productivity during and post-COVID-19: Results from an OECD survey among managers and workers.2021. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B14%5D%09Criscuolo%2C+C.%2C+Gal%2C+P.%2C+Leidecker%2C+T.%2C+Losma%2C+F.%2C+%26Nicoletti%2C+G.+%282021%29.+The+role+of+telework+for+productivity+during+and+post-COVID-19%3A+Results+from+an+OECD+survey+among+managers+and+workers.+&btnG= (accessed on 15 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Cuerdo-Vilches, T., Navas-Martín, M. Á., March, S., &Oteiza, I. . Adequacy of telework spaces in homes during the lockdown in Madrid, according to socioeconomic factors and home features. Sustainable Cities and Society, 2021. 75, 103262. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B15%5D%09Cuerdo-Vilches%2C+T.%2C+Navas-Mart%C3%ADn%2C+M.+%C3%81.%2C+March%2C+S.%2C+%26Oteiza%2C+I.+%282021%29.+Adequacy+of+telework+spaces+in+homes+during+the+lockdown+in+Madrid%2C+according+to+socioeconomic+factors+and+home+features.+Sustainable+Cities+and+Society%2C+75%2C+103262&btnG= (accessed on 16 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N., Dumitru, A., Anguelovski, I., Avelino, F., Bach, M., Best, B., ..&Rauschmayer, F. . Elucidating the changing roles of civil society in urban sustainability transitions. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 2016. 22, 41-50. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B16%5D%09Frantzeskaki%2C+N.%2C+Dumitru%2C+A.%2C+Anguelovski%2C+I.%2C+Avelino%2C+F.%2C+Bach%2C+M.%2C+Best%2C+B.%2C+..%26Rauschmayer%2C+F.+%282016%29.+Elucidating+the+changing+roles+of+civil+society+in+urban+sustainability+transitions.+Current+Opinion+in+Environmental+Sustainability%2C+22%2C+41-50&btnG=& (accessed on 15 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, R. S., & Harrison, D. A. .The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of applied psychology, 2007. 92(6), 1524. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B17%5D%09Gajendran%2C+R.+S.%2C+%26+Harrison%2C+D.+A.+%282007%29.+The+good%2C+the+bad%2C+and+the+unknown+about+telecommuting%3A+meta-analysis+of+psychological+mediators+and+individual+consequences.+Journal+of+applied+psychology%2C+92%286%29%2C+1524.+&btnG=& (accessed on 2 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, A., Tirado, F.&Martínez, M. J. .Work–life balance, organizations and social sustainability: Analyzing female telework in Spain. Sustainability, 2020. 12(9), 3567.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B18%5D%09G%C3%A1lvez%2C+A.%2C+Tirado%2C+F.%2C+%26Mart%C3%ADnez%2C+M.+J.+%282020%29.+Work%E2%80%93life+balance%2C+organizations+and+social+sustainability%3A+Analyzing+female+telework+in+Spain.+Sustainability%2C+12%289%29%2C+3567&btnG=&(accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, G. C., Matthews, L. J., Posard, M., Roshan, P., & Ross, S. M. .Evaluation of the military spouse employment partnership: Progress report on first stage of analysis. RAND Corporation National Defense Research Institute Santa Monica United States, 2015. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B19%5D%09Gonzalez%2C+G.+C.%2C+Matthews%2C+L.+J.%2C+Posard%2C+M.%2C+Roshan%2C+P.%2C+%26+Ross%2C+S.+M.+%282015%29.+Evaluation+of+the+military+spouse+employment+partnership%3A+Progress+report+on+first+stage+of+analysis.+RAND+Corporation+National+Defense+Research+Institute+Santa+Monica+United+States.+&btnG=&(accessed on 16 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Green, N., Tappin, D., & Bentley, T. . Exploring the Teleworking Experiences of Organisations in a Post-Disaster Environment. New Zealand Journal of Human Resources Management, 2017. 17(1). Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B20%5D%09Green%2C+N.%2C+Tappin%2C+D.%2C+%26+Bentley%2C+T.+%282017%29.+Exploring+the+Teleworking+Experiences+of+Organisations+in+a+Post-Disaster+Environment.+New+Zealand+Journal+of+Human+Resources+Management%2C+17%281%29.+&btnG=& (accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Greer, T. W., & Payne, S. C. . Overcoming telework challenges: Outcomes of successful telework strategies. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 2014.17(2), 87.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B21%5D%09Greer%2C+T.+W.%2C+%26+Payne%2C+S.+C.+%282014%29.+Overcoming+telework+challenges%3A+Outcomes+of+successful+telework+strategies.+The+Psychologist-Manager+Journal%2C+17%282%29%2C+87.&btnG=& (accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Grzegorczyk, M., Mariniello, M., Nurski, L., &Schraepen, T. .Blending the physical and virtual: a hybrid model for the future of work (No. 14/2021). Bruegel Policy Contribution, 2021. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B22%5D%09Grzegorczyk%2C+M.%2C+Mariniello%2C+M.%2C+Nurski%2C+L.%2C+%26Schraepen%2C+T.+%282021%29.+Blending+the+physical+and+virtual%3A+a+hybrid+model+for+the+future+of+work+%28No.+14%2F2021%29.+Bruegel+Policy+Contribution&btnG=&https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/blending-physical-and-virtual-hybrid-model-future-work(accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Harpaz, I. . Advantages and disadvantages of telecommuting for the individual, organization and society. Work study, 2002. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B23%5D%09Harpaz%2C+I.+%282002%29.+Advantages+and+disadvantages+of+telecommuting+for+the+individual%2C+organization+and+society.+Work+study&btnG=& (accessed on 16 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Haski-Leventhal, D., Hustinx, L., & Handy, F. . What money cannot buy: The distinctive and multidimensional impact of volunteers. Journal of Community Practice, 2011. 19(2), 138-158.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B24%5D%09Haski-Leventhal%2C+D.%2C+Hustinx%2C+L.%2C+%26+Handy%2C+F.+%282011%29.+What+money+cannot+buy%3A+The+distinctive+and+multidimensional+impact+of+volunteers.+Journal+of+Community+Practice%2C+19%282%29%2C+138-158&btnG=&https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10705422.2011.568930(accessed on 16 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D. A., Balbontin, C., Beck, M. J., & Wei, E. . The impact of working from home on modal commuting choice response during COVID-19: Implications for two metropolitan areas in Australia. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2022. 155, 179-201. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B25%5D%09Hensher%2C+D.+A.%2C+Balbontin%2C+C.%2C+Beck%2C+M.+J.%2C+%26+Wei%2C+E.+%282022%29.+The+impact+of+working+from+home+on+modal+commuting+choice+response+during+COVID-19%3A+Implications+for+two+metropolitan+areas+in+Australia.+Transportation+Research+Part+A%3A+Policy+and+Practice%2C+155%2C+179-201&btnG=& (accessed on 2 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Himawan, K. K., Helmi, J., &Fanggidae, J. P. . The sociocultural barriers of work-from-home arrangement due to COVID-19 pandemic in Asia: Implications and future implementation. Knowledge and Process Management, 2022. 29(2), 185-193. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B26%5D%09Himawan%2C+K.+K.%2C+Helmi%2C+J.%2C+%26Fanggidae%2C+J.+P.+%282022%29.+The+sociocultural+barriers+of+work%E2%80%90from%E2%80%90home+arrangement+due+to+COVID%E2%80%9019+pandemic+in+Asia%3A+Implications+and+future+implementation.+Knowledge+and+Process+Management%2C+29%282%29%2C+185-193.+&btnG=& (accessed on 8 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Hoch, J. E., & Kozlowski, S. W. . Leading virtual teams: Hierarchical leadership, structural supports, and shared team leadership. Journal of applied psychology, 2014. 99(3), 390. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B27%5D%09Hoch%2C+J.+E.%2C+%26+Kozlowski%2C+S.+W.+%282014%29.+Leading+virtual+teams%3A+Hierarchical+leadership%2C++structural+supports%2C+and+shared+team+leadership.+Journal+of+applied+psychology%2C+99%283%29%2C+390&btnG=& (accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Hook, A., Sovacool, B. K., & Sorrell, S. A systematic review of the energy and climate impacts of teleworking. Environmental Research Letters, 2020. 15(9), 093003. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B28%5D%09Hook%2C+A.%2C+Sovacool%2C+B.+K.%2C+%26+Sorrell%2C+S.+%282020%29.+A+systematic+review+of+the+energy+and+climate+impacts+of+teleworking.+Environmental+Research+Letters%2C+15%289%29%2C+093003.+&btnG=& (accessed on 16 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Hui, B. P., Ng, J. C., Berzaghi, E., Cunningham-Amos, L. A., &Kogan, A. . Rewards of kindness? A meta-analysis of the link between prosociality and well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 2020. 146(12), 1084. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B29%5D%09Hui%2C+B.+P.%2C+Ng%2C+J.+C.%2C+Berzaghi%2C+E.%2C+Cunningham-Amos%2C+L.+A.%2C+%26Kogan%2C+A.+%282020%29.+Rewards+of+kindness%3F+A+meta-analysis+of+the+link+between+prosociality+and+well-being.+Psychological+Bulletin%2C+146%2812%29%2C+1084&btnG=& (accessed on 16 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Haski-Leventhal, D., Hustinx, L., & Handy, F. . What money cannot buy: The distinctive and multidimensional impact of volunteers.Journal of Community Practice, 2011.19(2), 138-158.https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B30%5D%09Haski-Leventhal%2C+D.%2C+Hustinx%2C+L.%2C+%26+Handy%2C+F.+%282011%29.+What+money+cannot+buy%3A+The+distinctive+and+multidimensional+impact+of+volunteers.Journal+of+Community+Practice%2C+19%282%29&btnG=.

- Hustinx, L., Handy, F., &Cnaan, R. A. . Volunteering. Third sector research, 2010. 73-89. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B30%5D%09Haski-Leventhal%2C+D.%2C+Hustinx%2C+L.%2C+%26+Handy%2C+F.+%282011%29.+What+money+cannot+buy%3A+The+distinctive+and+multidimensional+impact+of+volunteers.Journal+of+Community+Practice%2C+19%282%29&btnG=&https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4419-5707-8_7(accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Iscan, O. F., &Naktiyok, A. . Attitudes towards telecommuting: the Turkish case. Journal of Information Technology, 2005. 20(1), 52-63. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B32%5D%09Iscan%2C+O.+F.%2C+%26Naktiyok%2C+A.+%282005%29.+Attitudes+towards+telecommuting%3A+the+Turkish+case.+Journal+of+Information+Technology%2C+20%281%29%2C+52-63.+&btnG=& (accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. A. . Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 2010. 83(4), 857-878. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B33%5D%09Jones%2C+D.+A.+%282010%29.+Does+serving+the+community+also+serve+the+company%3F+Using+organizational+identification+and+social+exchange+theories+to+understand+employee+responses+to+a+volunteerism+programme.+Journal+of+Occupational+and+Organizational+Psychology%2C+83%284%29%2C+857-878&btnG=& (accessed on 20 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. K., & Lee, L. .Overcoming Obstacles. Military Spouses with Graduate Degrees: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Thriving amidst Uncertainty, 2019. 197. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B34%5D%09Jones%2C+G.+K.%2C+%26+Lee%2C+L.+%282019%29.+Overcoming+Obstacles.+Military+Spouses+with+Graduate+Degrees%3A+Interdisciplinary+Approaches+to+Thriving+amidst+Uncertainty%2C+197.+&btnG=& (accessed on 20 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kalkbrenner, B. J., &Roosen, J. Citizens’ willingness to participate in local renewable energy projects: The role of community and trust in Germany. Energy Research & Social Science, 2016. 13, 60-70. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B33%5D%09Kalkbrenner%2C+B.+J.%2C+%26Roosen%2C+J.+%28%29.+Citizens%E2%80%99+willingness+to+participate+in+local+renewable+energy+projects%3A+The+role+of+community+and+trust+in+Germany.+Energy+Research+%26+Social+Science%2C+2016.+13%2C+60-70&btnG= & (accessed on 22 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kalter, M. J. O., Geurs, K. T., &Wismans, L. Post COVID-19 teleworking and car use intentions. Evidence from large scale GPS-tracking and survey data in the Netherlands. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 2021. 12, 100498. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B34%5D%09Kalter%2C+M.+J.+O.%2C+Geurs%2C+K.+T.%2C+%26Wismans%2C+L.+%282021%29.+Post+COVID-19+teleworking+and+car+use+intentions.+Evidence+from+large+scale+GPS-tracking+and+survey+data+in+the+Netherlands.+Transportation+Research+Interdisciplinary+Perspectives%2C+12%2C+100498&btnG=& (accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kamerade, D., &Burchell, B. Teleworking and participatory capital: Is teleworking an isolating or a community-friendly form of work?. European Sociological Review, 2004. 20(4), 345-361. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B34%5D%09Kalter%2C+M.+J.+O.%2C+Geurs%2C+K.+T.%2C+%26Wismans%2C+L.+%282021%29.+Post+COVID-19+teleworking+and+car+use+intentions.+Evidence+from+large+scale+GPS-tracking+and+survey+data+in+the+Netherlands.+Transportation+Research+Interdisciplinary+Perspectives%2C+12%2C+100498&btnG=#d=gs_cit&t=1685638806595&u=%2Fscholar%3Fq%3Dinfo%3AregdoIpvOKMJ%3Ascholar.google.com%2F%26output%3Dcite%26scirp%3D0%26hl%3Den& (accessed on 22 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Karia, N., &Asaari, M. H. A. H. Innovation capability: the impact of teleworking on sustainable competitive advantage. International Journal of Technology, Policy and Management, 2016. 16(2), 181-194. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B35%5D%09Karia%2C+N.%2C+%26Asaari%2C+M.+H.+A.+H.+%28%29.+Innovation+capability%3A+the+impact+of+teleworking+on+sustainable+competitive+advantage.+International+Journal+of+Technology%2C+Policy+and+Management%2C+2016.+16%282%29%2C+181-194.+&btnG= &(accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kirk, J., &Belovics, R. Making e-working work. Journal of Employment Counseling, 2006. 43(1), 39-46. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=kirk%2C+J.%2C+%26+Belovics%2C+R.+%28%29.+Making+e%E2%80%90working+work.+Journal+of+Employment+Counseling%2C+2006.+43%281%29%2C+39-46.+&btnG= & (accessed on 23 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kolakowski, H., Shepley, M. M., Valenzuela-Mendoza, E., &Ziebarth, N. R. How the COVID-19 pandemic will change workplaces, healthcare markets and healthy living: An overview and assessment. Sustainability, 2021. 13(18), 10096. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B37%5D%09Kolakowski%2C+H.%2C+Shepley%2C+M.+M.%2C+Valenzuela-Mendoza%2C+E.%2C+%26+Ziebarth%2C+N.+R.+%28%29.+How+the+COVID-19+pandemic+will+change+workplaces%2C+healthcare+markets+and+healthy+living%3A+An+overview+and+assessment.+Sustainability%2C+2021.+13%2818%29%2C+10096&btnG= & (accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Lebopo, C. M., Seymour, L. F., &Knoesen, H. Explaining factors affecting telework adoption in South African organisations pre-COVID-19. In Conference of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists 2020. 2020, September. (pp. 94-101). Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B38%5D%09Lebopo%2C+C.+M.%2C+Seymour%2C+L.+F.%2C+%26+Knoesen%2C+H.+%28%29.+Explaining+factors+affecting+telework+adoption+in+South+African+organisations+pre-COVID-19.+In+Conference+of+the+South+African+Institute+of+Computer+Scientists+and+Information+Technologists+2020.+2020%2C+September.+%28pp.+94+-101%29.+&btnG= & (accessed on 3 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P. M. COVID-19 and the new technologies of organizing: digital exhaust, digital footprints, and artificial intelligence in the wake of remote work. Journal of Management Studies, 2021. 58(1), 249. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B39%5D%09Leonardi%2C+P.+M.+%28%29.+COVID%E2%80%9019+and+the+new+technologies+of+organizing%3A+digital+exhaust%2C+digital+footprints%2C+and+artificial+intelligence+in+the+wake+of+remote+work.+Journal+of+Management+Studies%2C+2021.+58%281%29%2C+249&btnG= & (accessed on 16 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Lodovici, M. S., Ferrari, E., Paladino, E., Pesce, F., Frecassetti, P., & Aram, E. The impact of teleworking and digital work on workers and society. Study Requested by the EMPL Committee. 2021. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Lodovici%2C+M.+S.%2C+Ferrari%2C+E.%2C+Paladino%2C+E.%2C+Pesce%2C+F.%2C+Frecassetti%2C+P.%2C+%26+Aram%2C+E.+%28%29.+The+impact+of+teleworking+and+digital+work+on+workers+and+society.+Study+Requested+by+the+EMPL+Committee.+2021&btnG= &https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/662904/IPOL_STU(2021)662904_EN.pdf(accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Loia, F., &Adinolfi, P. Teleworking as an eco-innovation for sustainable development: Assessing collective perceptions during COVID-19. Sustainability, 2021. 13(9), 4823.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B41%5D%09Loia%2C+F.%2C+%26+Adinolfi%2C+P.+%28%29.+Teleworking+as+an+eco-innovation+for+sustainable+development%3A+Assessing+collective+perceptions+during+COVID-19.+Sustainability%2C+2021.+13%289%29%2C+4823.&btnG= & (accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Martins, A. D., &Sobral, S. R. Working and learning during the COVID-19 confinement: An exploratory analysis with a small sample from Portugal. Informatics. 2021, June.(Vol. 8, No. 3, p. 44). MDPI. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B42%5D%09Martins%2C+A.+D.%2C+%26+Sobral%2C+S.+R.+%28%29.+Working+and+learning+during+the+COVID-19+confinement%3A+An+exploratory+analysis+with+a+small+sample+from+Portugal.+In+Informatics.+2021%2C+June&btnG=& (accessed on 16 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, T., &Tietze, S. From anxiety to assurance: Concerns and outcomes of telework. Personnel Review, 2012. 41(4), 450-469.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Maruyama%2C+T.%2C+%26+Tietze%2C+S.+%28%29.+From+anxiety+to+assurance%3A+Concerns+and+outcomes+of+telework.+Personnel+Review%2C+2012.+41%284%29%2C+450-469.+&btnG= (accessed on 25 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Moens, E., Lippens, L., Sterkens, P., Weytjens, J., &Baert, S. The COVID-19 crisis and telework: a research survey on experiences, expectations and hopes. The European Journal of Health Economics, 2022. 23(4), 729-753. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B44%5D%09Moens%2C+E.%2C+Lippens%2C+L.%2C+Sterkens%2C+P.%2C+Weytjens%2C+J.%2C+%26Baert%2C+S.+%28%29.+The+COVID-19+crisis+and+telework%3A+a+research+survey+on+experiences%2C+expectations+and+hopes.+The+European+Journal+of+Health+Economics%2C+2022.+23%284%29%2C+729-753.+&btnG= (accessed on 28 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Moglia, M., Hopkins, J., &Bardoel, A. Telework, hybrid work and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals: towards policy coherence. Sustainability, 2021. 13(16), 9222. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B45%5D%09Moglia%2C+M.%2C+Hopkins%2C+J.%2C+%26+Bardoel%2C+A.+%28%29.+Telework%2C+hybrid+work+and+the+United+Nation%E2%80%99s+Sustainable+Development+Goals%3A+towards+policy+coherence.+Sustainability%2C+2021.+13%2816%29%2C+9222.+&btnG=(accessed on 1 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M. Productivity of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from an employee survey. Covid Economics, 2020. 49, 123-139. Available online: https://cepr.org/system/files/publication-files/101401-covid_economics_issue_49.pdf#page=128 (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Nakanishi, H. Does telework really save energy?. International Management Review, 2015. 11(2), 89-97. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B47%5D%09Nakanishi%2C+H.+%28%29.+Does+telework+really+save+energy%3F.+International+Management+Review%2C+2015.+11%282%29%2C+89-97&btnG= &https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Hodaka-Nakanishi-2/publication/280599807_Energy_Saving_Effects_of_Telework/links/5ec319bca6fdcc90d6825a1b/Energy-Saving-Effects-of-Telework.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Niebuhr, F., Borle, P., Börner-Zobel, F., &Voelter-Mahlknecht, S. Healthy and happy working from home? Effects of working from home on employee health and job satisfaction. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2022. 19(3), 1122. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%2C+F.%2C+Borle%2C+P.%2C+B%C3%B6rner-Zobel%2C+F.%2C+%26+Voelter-Mahlknecht%2C+S.+%28%29.+Healthy+and+happy+working+from+home%3F+Effects+of+working+from+home+on+employee+health+and+job+satisfaction.+International+journal+of+environmental+research+and+public+health%2C+2022.+19%283%29%2C+1122.+&btnG= (accessed on 16 May 2023). https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/3/1122.

- Oakman, J., Kinsman, N., Stuckey, R., Graham, M., &Weale, V. A rapid review of mental and physical health effects of working at home: how do we optimise health? BMC public health, 2020. 20, 1-13. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B49%5D%09Oakman%2C+J.%2C+Kinsman%2C+N.%2C+Stuckey%2C+R.%2C+Graham%2C+M.%2C+%26+Weale%2C+V.+%28%29.+A+rapid+review+of+mental+and+physical+health+effects+of+working+at+home%3A+how+do+we+optimise+health%3F.+BMC+public+health%2C+2020.+20%2C+1-13.+&btnG= (accessed on 29 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, W., &Aliabadi, F. Y. Does telecommuting save energy? A critical review of quantitative studies and their research methods. Energy and Buildings, 2020. 225, 110298.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=O%27Brien%2C+W.%2C+%26Aliabadi%2C+F.+Y.+%282020%29.+Does+telecommuting+save+energy%3F+A+critical+review+of+quantitative+studies+and+their+research+methods.+Energy+and+Buildings%2C+225%2C+110298&btnG= (accessed on 16 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Obrenovic, B., Du, J., Godinic, D., Tsoy, D., Khan, M. A. S., &Jakhongirov, I. Sustaining enterprise operations and productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic:“Enterprise Effectiveness and Sustainability Model”. Sustainability, 2020. 12(15), 5981. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B51%5D%09Obrenovic%2C+B.%2C+Du%2C+J.%2C+Godinic%2C+D.%2C+Tsoy%2C+D.%2C+Khan%2C+M.+A.+S.%2C+%26+Jakhongirov%2C+I.+%28%29.+Sustaining+enterprise+operations+and+productivity+during+the+COVID-19+pandemic%3A%E2%80%9CEnterprise+Effectiveness+and+Sustainability+Model%E2%80%9D.+Sustainability%2C+2020.+12%2815%29%2C+5981.&btnG= (accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Teleworking in the COVID-19 pandemic: trends and prospects. Paris: OECD Publishing.2021. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B52%5D%09Organisation+for+Economic+Co-operation+and+Development.+%28%29.+Teleworking+in+the+COVID-19+pandemic%3A+trends+and+prospects.+Paris%3A+OECD+Publishing.+2021&btnG= (accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Pan, S. Y., Gao, M., Kim, H., Shah, K. J., Pei, S. L., & Chiang, P. C. Advances and challenges in sustainable tourism toward a green economy. Science of the total environment, 2018. 635, 452-469. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B53%5D%09Pan%2C+S.+Y.%2C+Gao%2C+M.%2C+Kim%2C+H.%2C+Shah%2C+K.+J.%2C+Pei%2C+S.+L.%2C+%26+Chiang%2C+P.+C.+%28%29.+Advances+and+challenges+in+sustainable+tourism+toward+a+green+economy.+Science+of+the+total+environment%2C+2018.+635%2C+452-469&btnG= (accessed on 7 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Parks, A., &Rauchwerger, J. First Food Responders: People are Hungry. Feed Them Now! Here’s How. Morgan James Publishing, 2023.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Parks%2C+A.%2C+%26Rauchwerger%2C+J.+%282023%29.+First+Food+Responders%3A+People+are+Hungry.+Feed+Them+Now%21+Here%E2%80%99s+How.+Morgan+James+Publishing&btnG= (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Pordelan, N., Hosseinian, S., Heydari, H., Khalijian, S., &Khorrami, M. Consequences of teleworking using the internet among married working women: Educational careers investigation. Education and Information Technologies, 2022. 27(3), 4277-4299.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B55%5D%09Pordelan%2C+N.%2C+Hosseinian%2C+S.%2C+Heydari%2C+H.%2C+Khalijian%2C+S.%2C+%26Khorrami%2C+M.+%28%29.+Consequences+of+teleworking+using+the+internet+among+married+working+women%3A+Educational+careers+investigation.+Education+and+Information+Technologies%2C+2022.+27%283%29%2C+4277-4299.&btnG= (accessed on 30 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Raišienė, A. G., Rapuano, V., Varkulevičiūtė, K., &Stachová, K. Working from home—Who is happy? A survey of Lithuania’s employees during the COVID-19 quarantine period. Sustainability, 2020. 12(13), 5332. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B56%5D%09Rai%C5%A1ien%C4%97%2C+A.+G.%2C+Rapuano%2C+V.%2C+Varkulevi%C4%8Di%C5%ABt%C4%97%2C+K.%2C+%26Stachov%C3%A1%2C+K.+%28%29.+Working+from+home%E2%80%94Who+is+happy%3F+A+survey+of+Lithuania%E2%80%99s+employees+during+the+COVID-19+quarantine+period.+Sustainability%2C+2020.+12%2813&btnG= (accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Raišienė, A. G., Rapuano, V., Dőry, T., &Varkulevičiūtė, K. Does telework work? Gauging challenges of telecommuting to adapt to a “new normal”. Human technology, 2021. 17(2), 126. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B57%5D%09Rai%C5%A1ien%C4%97%2C+A.+G.%2C+Rapuano%2C+V.%2C+D%C5%91ry%2C+T.%2C+%26+Varkulevi%C4%8Di%C5%ABt%C4%97%2C+K.+%28%29.+Does+telework+work%3F+Gauging+challenges+of+telecommuting+to+adapt+to+a+%E2%80%9Cnew+normal%E2%80%9D.+Human+technology%2C+2021.+17%282%29%2C+126.+&btnG= & https://media.proquest.com/media/hms/PFT/1/oP6JN?_s=uBeXmh9gJbPr9elBkz75EIjORW0%3D (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- Rao, V. Innovation through employee engagement. Asia Pacific Journal of Advanced Business and Social Studies, 2016. 2(2), 337-345. Available online: https://apiar.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/APCAR_BRR710_BUS1-9.pdf(accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Spagnoli, P., Molino, M., Molinaro, D., Giancaspro, M. L., Manuti, A., &Ghislieri, C. Workaholism and technostress during the COVID-19 emergency: The crucial role of the leaders on remote working. Frontiers in psychology, 2020. 11, 620310. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B59%5D%09Spagnoli%2C+P.%2C+Molino%2C+M.%2C+Molinaro%2C+D.%2C+Giancaspro%2C+M.+L.%2C+Manuti%2C+A.%2C+%26Ghislieri%2C+C.+%28%29.+Workaholism+and+technostress+during+the+COVID-19+emergency%3A+The+crucial+role+of+the+leaders+on+remote+working.+Frontiers+in+psychology%2C+2020.+11%2C+620310&btnG= (accessed on 21 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Schuster, C., Weitzman, L., SassMikkelsen, K., Meyer-Sahling, J., Bersch, K., Fukuyama, F., ..& Kay, K. Responding to COVID-19 through surveys of public servants. Public Administration Review, 2020. 80(5), 792-796. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B60%5D%09Schuster%2C+C.%2C+Weitzman%2C+L.%2C+SassMikkelsen%2C+K.%2C+Meyer%E2%80%90Sahling%2C+J.%2C+Bersch%2C+K.%2C+Fukuyama%2C+F.%2C+..%26+Kay%2C+K.+%28%29.+Responding+to+COVID%E2%80%9019+through+surveys+of+public+servants.+Public+Administration+Review%2C+2020.+80%285%29%2C+792-796.+&btnG= (accessed on 7 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R. J., Payne, S. C., Alexander, A. L., Gaskins, V. A., & Henning, J. B. A taxonomy of employee motives for telework. Occupational Health Science, 2021. 1-32. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Thompson%2C+R.+J.%2C+Payne%2C+S.+C.%2C+Alexander%2C+A.+L.%2C+Gaskins%2C+V.+A.%2C+%26+Henning%2C+J.+B.+%28%29.+A+taxonomy+of+employee+motives+for+telework.+Occupational+Health+Science%2C+2021.+1-32.+&btnG= (accessed on 7 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Tomaz, E., Moriset, B., & Teller, J. Rural coworking spaces in the COVID-19 era: A window of opportunity?. In The covid-19 pandemic and the future of working spaces (pp. 122-135). Routledge. 2022. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B62%5D%09Tomaz%2C+E.%2C+Moriset%2C+B.%2C+%26+Teller%2C+J.+%28%29.+Rural+coworking+spaces+in+the+COVID-19+era%3A+A+window+of+opportunity%3F.+In+The+covid-19+pandemic+and+the+future+of+working+spaces+%28pp.+122-135%29.+Routledge.+2022&btnG= (accessed on 5 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Tomislav, K. The concept of sustainable development: From its beginning to the contemporary issues. Zagreb International Review of Economics & Business, 21(1), 2018. 67-94.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B63%5D%09Tomislav%2C+K.+%28%29.+The+concept+of+sustainable+development%3A+From+its+beginning+to+the+contemporary+issues.+Zagreb+International+Review+of+Economics+%26+Business%2C+21%281%29%2C+2018.+67-94&btnG= (accessed on 2 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Tsekouropoulos, G., Gkouna, O., Theocharis, D., &Gounas, A. Innovative sustainable tourism development and entrepreneurship through sports events. Sustainability, 2022. 14(8), 4379.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Tsekouropoulos%2C+G.%2C+Gkouna%2C+O.%2C+Theocharis%2C+D.%2C+%26Gounas%2C+A.+%28%29.+Innovative+sustainable+tourism+development+and+entrepreneurship+through+sports+events.+Sustainability%2C+2022.+14%288%29%2C+4379.&btnG= (accessed on 2 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Türkeș, M. C., &Vuță, D. R. Telework: Before and after COVID-19. Encyclopedia, 2022. 2(3), 1370-1383. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%2C+M.+C.%2C+%26+Vu%C8%9B%C4%83%2C+D.+R.+%28%29.+Telework%3A+Before+and+after+COVID-19.+Encyclopedia%2C+2022.+2%283%29%2C+1370-1383&btnG= (accessed on 17 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Van der Merwe, F. I., & Smith, D. C. Telework: Enablers and moderators when assessing organisational fit. Proceedings of the Southern African Institute for Computer Scientist and Information Technologists Annual Conference 2014 on SAICSIT 2014 Empowered by Technology, 2014, September. (pp. 323-333). Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B67%5D%09Van+der+Merwe%2C+F.+I.%2C+%26+Smith%2C+D.+C.+%28%29.+Telework%3A+Enablers+and+moderators+when+assessing+organisational+fit.+In+Proceedings+of+the+Southern+African+Institute+for+Computer+Scientist+and+Information+Technologists+Annual+Conference+2014+on+SAICSIT+2014+Empowered+by+Technology%2C+2014%2C+September.+%28pp.+323-333%29.+&btnG= (accessed on 25 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Van Lier, T., De Witte, A., &Macharis, C. How worthwhile is teleworking from a sustainable mobility perspective? The case of Brussels Capital region. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 2014. 14(3).Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B68%5D%09Van+Lier%2C+T.%2C+De+Witte%2C+A.%2C+%26Macharis%2C+C.+%28%29.+How+worthwhile+is+teleworking+from+a+sustainable+mobility+perspective%3F+The+case+of+Brussels+Capital+region.+European+Journal+of+Transport+and+Infrastructure+Research%2C+2014.+14%283%29.&btnG= (accessed on 5 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Vrana, V. Sustainable Tourism Development and Innovation: Recent Advances and Challenges. Sustainability, 2023. 15(9), 7224.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Vrana%2C+V.+%28%29.+Sustainable+Tourism+Development+and+Innovation%3A+Recent+Advances+and+Challenges.+Sustainability%2C+2023.+15%289%29%2C+7224.&btnG= (accessed on 2 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Wojcak, E., Bajzikova, L., Sajgalikova, H., &Polakova, M. How to achieve sustainable efficiency with teleworkers: Leadership model in telework. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2016. 229, 33-41. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B70%5D%09Wojcak%2C+E.%2C+Bajzikova%2C+L.%2C+Sajgalikova%2C+H.%2C+%26+Polakova%2C+M.+%28%29.+How+to+achieve+sustainable+efficiency+with+teleworkers%3A+Leadership+model+in+telework.+Procedia-Social+and+Behavioral+Sciences%2C+2016.+229%2C+33-41.+&btnG= (accessed on 24 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Grobler, P. A., & De Bruyn, A. J. Flexible Work Practices (FWP)-an effective instrument in the retention of talent: a survey of selected JSE-listed companies, South African Journal of Business Management, 42 (4) December 2011: pp. 63-78. South African Journal of Business Management, 2012. 43(1), 93. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B71%5D%09Grobler%2C+P.+A.%2C+%26+De+Bruyn%2C+A.+J.+%28%29.+Flexible+Work+Practices+%28FWP%29-an+effective+instrument+in+the+retention+of+talent%3A+a+survey+of+selected+JSE-listed+companies%2C+South+African+Journal+of+Business+Management%2C+42+%284%29+December+2011%3A+pp.+63-78.+South+African+Journal+of+Business+Management%2C+2012.+43%281%29%2C+&btnG= (accessed on 21 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Schwarzmüller T, Brosi P, Welpe IM. Digital Work Design–Wie die DigitalisierungGeschäftsmodelle, Arbeit und Führungverändert. München: TechnischeUniversitätMünchen. 2017. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=https%3A%2F%2Flink.springer.com%2Fbook%2F10.1007%2F978-3-662-53202-7&btnG=#d=gs_cit&t=1685475189842&u=%2Fscholar%3Fq%3Dinfo%3ANncc_ITk7iUJ%3Ascholar.google.com%2F%26output%3Dcite%26scirp%3D0%26hl%3Den&https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303984407_Fuhrung_40_-_Wie_die_Digitalisierung_Fuhrung_verandert(accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Jones, A. A qualitative multi-level analysis of factors influencing the diffusion and practice of teleworking among employees: insights from within three organisations. Ph.D. Dissertation, King’s College London (University of London). 2013. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=Jones,+A.++A+qualitative+multi-level+analysis+of+factors+influencing+the+diffusion+and+practice+of+teleworking+among+employees:+insights+from+within+three+organisations.+Ph.D.+Dissertation,+King%E2%80%99s+College+London+(University+of+London).+2013.&hl=el&as_sdt=0,5&https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.628349(accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Blount, Y. Pondering the fault lines of anywhere working (telework, telecommuting): A literature review. Foundations and Trends® in Information Systems, 2015. 1(3), 163-276. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Blount%2C+Y.+%28%29.+Pondering+the+fault+lines+of+anywhere+working+%28telework%2C+telecommuting%29%3A+A+literature+review.+Foundations+and+Trends%C2%AE+in+Information+Systems%2C+2015.+1%283%29%2C+163-276&btnG= (accessed on 7 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, D. Work-life balance, travel-to-work, and the dual career household. Personnel review, 2012. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Wheatley%2C+D.+%28%29.+Work%E2%80%90life+balance%2C+travel%E2%80%90to%E2%80%90work%2C+and+the+dual+career+household.+Personnel+review%2C+2012.+&btnG= (accessed on 4 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Chung, H., & Van der Lippe, T. Flexible working, work–life balance and gender equality: Introduction. Social Indicators Research, 2020. 151(2), 365-381. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Chung%2C+H.%2C+%26+Van+der+Lippe%2C+T.+%28%29.+Flexible+working%2C+work%E2%80%93life+balance+and+gender+equality%3A+Introduction.+Social+Indicators+Research%2C+2020.+151%282%29%2C+365-381&btnG= (accessed on 6 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Mattern, F., Staake, T., & Weiss, M. ICT for green: how computers can help us to conserve energy. In Proceedings of the 1st international conference on energy-efficient computing and networking (pp. 1-10). 2010, April . Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Mattern%2C+F.%2C+Staake%2C+T.%2C+%26+Weiss%2C+M.+%28%29.+ICT+for+green%3A+how+computers+can+help+us+to+conserve+energy.+In+Proceedings+of+the+1st+international+conference+on+energy-efficient+computing+and+networking+%28pp.+1-10%29.+2010%2C+April+&btnG=& (accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Harker Martin, B., & MacDonnell, R. Is telework effective for organizations? A meta-analysis of empirical research on perceptions of telework and organizational outcomes. Management Research Review, 2012. 35(7), 602-616. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Harker+Martin%2C+B.%2C+%26+MacDonnell%2C+R.+%28%29.+Is+telework+effective+for+organizations%3F+A+meta%E2%80%90analysis+of+empirical+research+on+perceptions+of+telework+and+organizational+outcomes.+Management+Research+Review%2C+2012.+35%287%29%2C+602-616&btnG= (accessed on 7 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Pyöriä, P. Managing telework: risks, fears and rules. Management Research Review, 2011. 34(4), 386-399.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Py%C3%B6ri%C3%A4%2C+P.+%28%29.+Managing+telework%3A+risks%2C+fears+and+rules.+Management+Research+Review%2C+2011.+34%284%29%2C+386-399.Available+online&btnG=& (accessed on 27 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Turetken, O., Jain, A., Quesenberry, B., &Ngwenyama, O. An empirical investigation of the impact of individual and work characteristics on telecommuting success. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 2010. 54(1), 56-67. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Turetken%2C+O.%2C+Jain%2C+A.%2C+Quesenberry%2C+B.%2C+%26+Ngwenyama%2C+O.+%28%29.+An+empirical+investigation+of+the+impact+of+individual+and+work+characteristics+on+telecommuting+success.+IEEE+Transactions+on+Professional+Communication%2C+2010.+54%281%29%2C+56-67&btnG= &(accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ceurstemont S. Teleworking is here to stay–here’s what it means for the future of work. Horizon–The EU Research & Innovation Magazine. 2020 Sep;1(9):2020.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B82%5D%09Ceurstemont%2C+S.+%282020%29.+Teleworking+is+here+to+stay%E2%80%93here%E2%80%99s+what+it+means+for+the+future+of+work.+Horizon%E2%80%93The+EU+Research+%26+Innovation+Magazine%2C+1%289%29%2C+&btnG= &.https://ec.europa.eu/research-and-innovation/en/horizon-magazine/teleworking-here-stay-heres-what-it-means-future-work.(accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Thomas DC, Pekerti AA. Effect of culture on situational determinants of exchange behavior in organizations: A comparison of New Zealand and Indonesia. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2003 May;34(3):269-81. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&as_ylo=2003&as_yhi=2005&q=Thomas%2C+D.C.+and+Pekerti%2C+Andre+A.+%282003%29.+Effect+of+culture+on+situational+determinants+of+exchange+behaviour+in+organizations%3A+A+comparison+on+New+Zealand+and+Indonesia.+Journal+of+Cross-Cultural+Psychology+34%283%29%3A+269-281.&btnG=& (accessed on 20 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Tavares, F., Santos, E., Diogo, A., &Ratten, V. Teleworking in Portuguese communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Enterprising Communities: people and places in the global economy, 2021. 15(3), 334-349.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=el&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%5B83%5D%09Tavares%2C+F.%2C+Santos%2C+E.%2C+Diogo%2C+A.%2C+%26Ratten%2C+V.+%28%29.+Teleworking+in+Portuguese+communities+during+the+COVID-19+pandemic.+Journal+of+Enterprising+Communities%3A+people+and+places+in+the+global+economy%2C+2021.+15%283%29%2C+334-349.&btnG= (accessed on 19 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N. Hybrid is the future of work. Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR): Stanford, CA, USA. 2021. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Hybrid+is+the+Future+of+Work&author=Bloom,+N.&publication_year=2021(accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Grant CA, Wallace LM, Spurgeon PC. An exploration of the psychological factors affecting remote e-worker's job effectiveness, well-being and work-life balance. Employee Relations. 2013 Aug 9.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Grant%2C+C.+%2C+Wallace%2C+L.M.+and+Spurgeon%2C+P.C.+%282013%29+An+exploration+of+the+psychological+factors+affecting+remote+e-worker%27s+job+effectiveness%2C+well-being+and+work-life+balance.+Employee+Relations%2C+volume+35+%285%29%3A+527-546.+http%3A%2F%2Fdx.doi.org%2F10.1108%2FER-08-2012-0059&btnG=#d=gs_cit&t=1685735673440&u=%2Fscholar%3Fq%3Dinfo%3Ai9ISXiwRoZMJ%3Ascholar.google.com%2F%26output%3Dcite%26scirp%3D0%26hl%3Den& (accessed on 19 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Karanikas N, Cauchi J. Literature review on parameters related to Work-From-Home (WFH) arrangements. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=https%3A%2F%2Feprints.qut.edu.au%2F205308%2F&btnG= & (accessed on 19 May 2023). https://eprints.qut.edu.au/205308/.

- och Regeringskansliet R. The Global Goals and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.2015. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=The+Global+Goals+and+the+2030+Agenda+for+Sustainable+Development+is+a+chain+of+reflection%2C+commitment+and+concerted+action+that+seek+to+end+poverty+and+hunger%2C+realize+the+human+rights+of+all%2C+achieve+gender+equality+and+empower+all+women+and+girls%2C+and+ensure+the+sustainable+protection+of+the+planet+and+its+natural+resources.&btnG=#d=gs_cit&t=1685785486538&u=%2Fscholar%3Fq%3Dinfo%3Ay4Xpg83dVEcJ%3Ascholar.google.com%2F%26output%3Dcite%26scirp%3D0%26hl%3Den&https://www.government.se/government-policy/the-global-goals-and-the-2030-Agenda-for-sustainable-development/(accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Capraro V, Boggio P, Böhm R, Perc M, Sjåstad H. Cooperation and acting for the greater good during the COVID-19 pandemic.2021. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Capraro%2C+V.%2C+Boggio%2C+P.%2C+B%C3%B6hm%2C+R.%2C+Perc%2C+M.%2C+%26+Sj%C3%A5stad%2C+H.+%282021%29.+Cooperation+and+acting+for+the+greater+good+during+the+COVID-19+pandemic.&btnG=&https://psyarxiv.com/65xmg/download?format=pdf(accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Zaki J. Catastrophe compassion: Understanding and extending prosociality under crisis. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2020 Aug 1;24(8):587-9. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Zaki%2C+J.+%282020%29.+Catastrophe+compassion%3A+Understanding+and+extending+prosociality+under+crisis.+Trends+in+Cognitive+Sciences%2C+24%2C+587-589.&btnG=#d=gs_cit&t=1685790024776&u=%2Fscholar%3Fq%3Dinfo%3AHY4N_DSHm1IJ%3Ascholar.google.com%2F%26output%3Dcite%26scirp%3D0%26hl%3Den&https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364661320301182(accessed on 3 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Savić D. COVID-19 and work from home: Digital transformation of the workforce. Grey Journal (TGJ). 2020 May;16(2):101-4. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Savi%C4%87+D.+COVID-19+and+work+from+home%3A+Digital+transformation+of+the+workforce.+Grey+Journal+%28TGJ%29.+2020+May%3B16%282%29%3A101-4.&btnG=&https://dobrica.savic.ca/pubs/TGJ_V16_N2_Summer_2020_DS_article.pdf(accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Winkler K, Heim N, Heinz T. Transformationale Führung im Zeitalter der Digitalisierung: Ein Denkmodell. Human Digital Work–Eine Utopie? Erkenntnisse aus Forschung und Praxis zur digitalen Transformation der Arbeit. 2020:189-204. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=70.%09Winkler%2C+K.%2C+Heim%2C+N.%2C+Heinz%2C+T.+%282020%29%2C+Transformationale+F%C3%BChrung+im+Zeitalter+der+Digitalisierung+%28Transformational+leadership+in+the+age+of+digitization%29.&btnG=#d=gs_cit&t=1685796100088&u=%2Fscholar%3Fq%3Dinfo%3A6faW50KqcmUJ%3Ascholar.google.com%2F%26output%3Dcite%26scirp%3D0%26hl%3Den&https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-658-26798-8_10(accessed on 3 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Frishammar J, Parida V. Circular business model transformation: A roadmap for incumbent firms. California Management Review. 2019 Feb;61(2):5-29. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Frishammar%2C+J.%2C+%26+Parida%2C+V.+%282019%29.+Circular+business+model+transformation%3A+A+roadmap+for+incumbent+firms.+California+Management+Review%2C+61%282%29%2C+5-29.&btnG= &https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0008125618811926(accessed on 3 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Betz, A. & Martin, B. (2018). Buurtzorg Britain & Ireland: Transforming the national health service when resources are scarce, Available online: https://enliveningedge.org/organizations/buurtzorg-uk-ireland-transforming-national-health-service-resources-scarce-part-1-shifting-mindsets/(accessed on 3 June 2023).