Submitted:

28 June 2023

Posted:

29 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Study Population

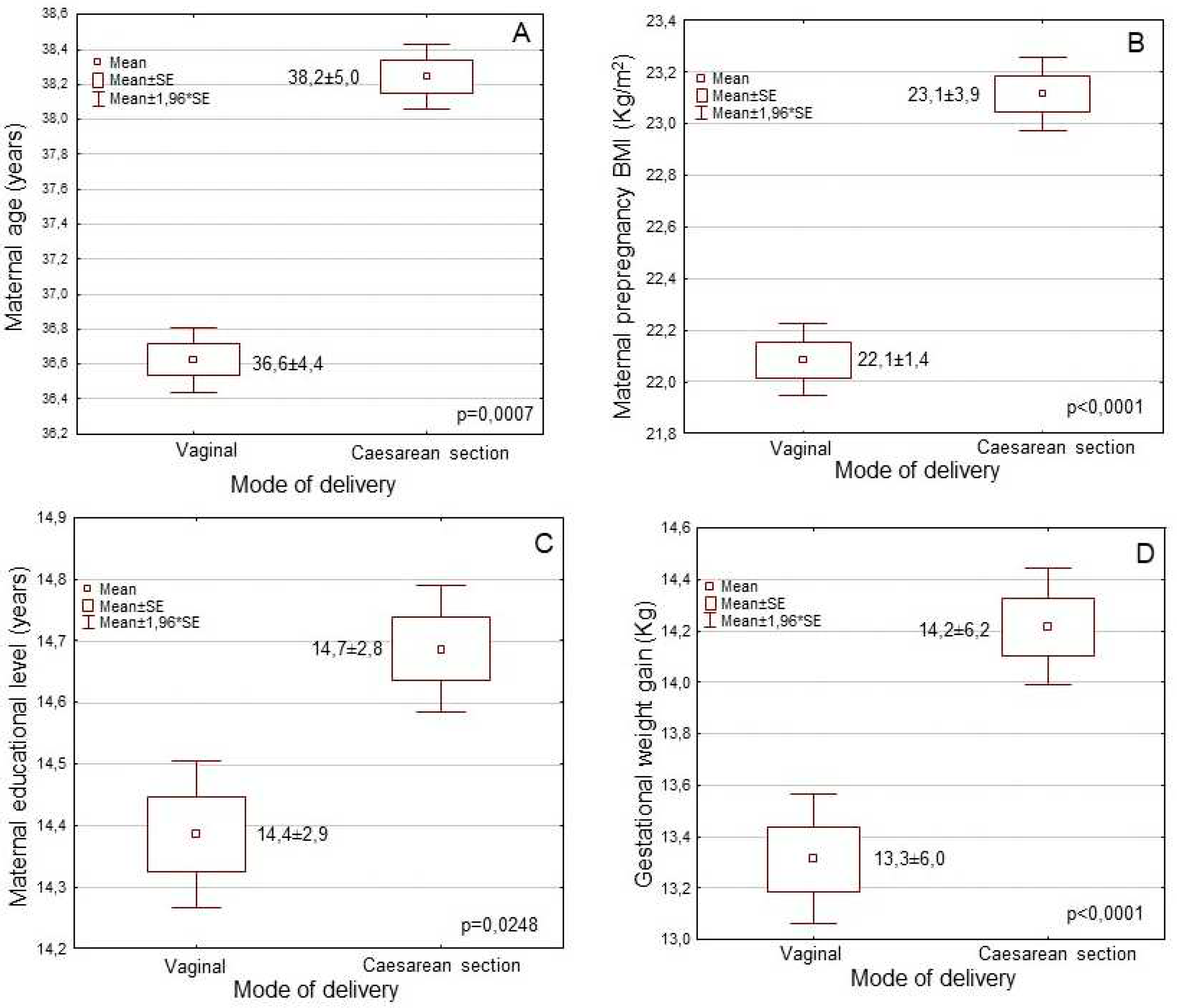

3.2. Associations of the Mode of Delivery with Sociodemographic, Anthropometric and Lifestyle Characteristics of the Participant Women

3.3. Associations of Mode of Delivery with Maternal Perinatal Factors

3.4. Multivariate Regression Analysis for Mode of Delivery by Adjustment for Multiple Confounding Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Betran, A.; Torloni, M.R.; Zhang, J.J.; et al. WHO statement on caesarean section rates. BJOG 2016, 123, 667–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betrán, A.P.; Ye, J.; Moller, A.B.; et al. The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: global, regional and national estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0148343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betran, A.P.; Ye, J.; Moller, A.B.; et al. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health 2021, 6, e005671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalkidis. Y.; Petridou, E.; Papathoma, E.; et al. Are operative delivery procedures in Greece socially conditioned? Int J Qual Health Care 1996, 8, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossialos, E.; Allin, S.; Karras, K.; et al. An investigation of Caesarean sections in three Greek hospitals: the impact of financial incentives and convenience. Eur J Public Health 2005, 15, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giaxi, P.; Gourounti, K.; Vivilak,i V. G.; et al. Which classification system could empower the understanding of caesarean section rates in Greece? A review of systematic reviews. Eur J Midwifer. 2022, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsdóttir, K.; Haggar, F.; Pereira, G.; et al. Role of public and private funding in the rising caesarean section rate: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, G.H.; Ayres-de-Campos, D.; Barnea, E.R.; et al. FIGO position paper: How to stop the caesarean section epidemic. Lancet 2018, 392, 1286–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandall, J.; Tribe, R.M.; Avery, L.; et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet 2018, 392, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, S.; Ein-Dor, T.; Berman, Z.; et al. Delivery mode is associated with maternal mental health following childbirth. Archiv Womens Ment Health 2019, 22, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, J.; Liu, J. Time to consider the risks of caesarean delivery for long term child health. BMJ. 2015, 350, h2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, G.H. Women are designed to deliver vaginally and not by cesarean section: An obstetrician's view. Neonatology 2015, 107, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizan JB, Amabebe E. Maternal obesity as a risk factor for caesarean delivery in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Life (Basel) 2022, 12, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal' Maso, E.; Rodrigues, P.R.M.; Ferreira, M.G.; et al. Cesarean birth and risk of obesity from birth to adolescence: A cohort study. Birth 2022, 49, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.; Samad, N.; Sapkota, A.; et al. Prevalence and factors associated with caesarean delivery in Nepal: Evidence from a nationally representative sample. Cureus 2021, 13, e20326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A,K. ; Dhungel, B.; Rahman, M. Trends and correlates of cesarean section rates over two decades in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzakpasu, S.; Fahey, J.; Kirby, R.S.; et al. Contribution of prepregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain to caesarean birth in Canada. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, D.M.; Larson, J.; Jacobsson, B.; et al. Cross-country individual participant analysis of 4.1 million singleton births in 5 countries with very high human development index confirms known associations but provides no biologic explanation for 2/3 of all preterm births. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0162506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.; Fong, R.; Murray, S.M.; et al. Caesarean birth and risk of subsequent preterm birth: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2021, 128, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiolna, M.; Kostiv, V.; Anthoulakis, C.; et al. Prediction of adverse perinatal outcome by cerebroplacental ratio in women undergoing induction of labor. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019, 53, 473–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbandi, M.; Rezaeian, S.; Dianatinasab, M.; et al. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and its association with stillbirth, preterm birth, macrosomia, abortion and cesarean delivery: a national prevalence study of 11 provinces in Iran. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022, 62, E885–E891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzorou, M.; Papandreou, D.; Vasios, G.K.; Pavlidou, E.; Antasouras, G.; Psara, E.; Taha, Z.; Poulios, E.; Giaginis, C. Exclusive breastfeeding for at least four months is associated with a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity in mothers and their children after 2-5 years from delivery. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, D.; Homer, C.; Wilson, A.; et al. Indications for, and timing of, planned caesarean section: A systematic analysis of clinical guidelines. Women Birth 2020, 33, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutelidakis, A.E.; Alexatou, O.; Kousaiti, S.; Gkretsi, E.; Vasios, G.; Sampani, A.; Tolia, M.; Kiortsis, D.N.; Giaginis, C. Higher adherence to Mediterranean diet prior to pregnancy is associated with decreased risk for deviation from the maternal recommended gestational weight gain. Int Food Sci Nutr. 2018, 69, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina G, Weiser TG, Lipsitz SR, et al. Relationship between caesarean delivery rate and maternal and neonatal mortality. JAMA. 2015, 314, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, Y.; Ibiebele, I.; Patterson, J.A.; et al. Rates of stillbirth by maternal region of birth and gestational age in New South Wales, Australia 2004-2015. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020, 60, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCourt, C.; Weaver, J.; Statham, H.; et al. Elective caesarean section and decision making: a critical review of the literature. Birth 2007, 34, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béhague, D.P. Beyond the simple economics of cesarean section birthing: women’s resistance to social inequality. Cult Med Psychiatry 2002, 26, 473–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, J.R.; Houck, K.M.; Bentley, M.E.; et al. Rising rates of cesarean delivery in Ecuador: Socioeconomic and institutional determinants over two decades. Birth 2019, 46, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attali, E.; Yogev, Y. The impact of advanced maternal age on pregnancy outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2021, 70, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, S.; Emeklioglu, C.N.; Cingillioglu, B.; et al. The effect of parity on obstetric and perinatal outcomes in pregnancies at the age of 40 and above: a retrospective study. Croat Med J. 2021, 62, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoud. ; Kelly, S.; Yasseen, A.; et al. Factors associated with increased rates of caesarean section in women of advanced maternal age. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015, 37, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budds, K.; Locke, A.; Burr, V. “For some people it isn’t a choice, it’s just how it happens”: Accounts of ‘delayed’ motherhood among middle-class women in the UK. Fem Psychol. 2016, 26, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, T.; Srivastava, S.; Kumar, P.; et al. Prevalence and predictors of elective and emergency caesarean delivery among reproductive-aged women in Bangladesh: evidence from demographic and health survey, 2017-18. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatta, F.; Sundby, J.; Vangen, S.; et al. Association between Maternal Origin, Pre-Pregnancy Body Mass Index and Caesarean Section: A Nation-Wide Registry Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Voerman, E.; Amiano, P.; et al. Impact of maternal body mass index and gestational weight gain on pregnancy complications: An individual participant data meta-analysis of European, North American, and Australian cohorts. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019, 126, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, S.D.; Pullenayegum, E.; Taylor, V.H.; et al. Despite 2009 guidelines, few women report being counseled correctly about weight gain during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011, 205, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers, B.; Dzakpasu, S.; Heaman, M.; et al. The Canadian maternity experiences survey: an overview of findings. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008, 30, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, F.C.; de Lyra Rabello Neto, D.; Villar, J.; et al. Caesarean sections and the prevalence of preterm and early-term births in Brazil: secondary analyses of national birth registration. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawanpaiboon, S.; Vogel, J.P.; Moller, A.-B.; et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2019, 7, e37–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackovic, M.; Milicic, B.; Mihajlovic, S.; et al. Gestational Diabetes and Risk Assessment of Adverse Perinatal Outcomes and Newborns Early Motoric Development. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021, 57, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renes, L.; Barka, N.; Gyurkovits, Z.; Paulik, E.; Nemeth. G.; Orvos, H. Predictors of caesarean section - a cross-sectional study in Hungary. J Maternal-Fetal Neonat Med. 2017, 31, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Begley, C.; Corcoran, P.; Daly, D. Factors associated with cesarean birth in nulliparous women: A multicenter prospective cohort study. Birth 2022, 49, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang. J.; et al. The association between caesarean delivery and the initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a prospective cohort study in China. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018, 72, 1644–1654. [CrossRef]

- Hoang Nguyen, P.T.; Binns, C.W.; Vo, Van Ha A.; et al. Caesarean delivery associated with adverse breastfeeding practices: a prospective cohort study. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020, 40, 644–648. [CrossRef]

- Sodeno, M.; Tappis, H.; Burnham, G.; Ververs, M. Associations between caesarean births and breastfeeding in the Middle East: a scoping review. East Mediterr Health J. 2021, 27, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics (n=5182) | Mode of delivery | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal (43.6%) |

Caesarean (56.4%) |

p-value | |

| Mothers’ age (mean±SD; years) | 36.6±4.4 | 38.2±5.0 | p = 0.0001 |

| Mothers’ nationality (n, %) | p = 0.4735 | ||

| Greek | 2169 (95.9) | 2788 (95.5) | |

| Others | 93 (4.1) | 132 (4.5) | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (mean±SD;Kg/m2) | 22.1±3.4 | 23.1±3.8 | p = 0.0001 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI status (n,%) | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Underweight | 98 (4.3) | 51 (1.8) | |

| Normal weight | 1751 (77.4) | 2118 (72.5) | |

| Overweight | 352 (15.6) | 553 (18.9) | |

| Obese | 61 (2.7) | 198 (6.6) | |

| Education level (mean±SD; years) | 14.3±2.9 | 14.7±2.8 | p = 0.0011 |

| Economic status (n, %) | p = 0.0117 | ||

| Low | 1082 (47.8) | 1315 (45.0) | |

| Medium | 1011 (44.7) | 1325 (45.4) | |

| High | 169 (7.5) | 280 (9.6) | |

| Smoking habits (n, %) | p = 0.0004 | ||

| No smokers | 1739 (76.9) | 2118 (72.5) | |

| Smokers | 523 (23.1) | 802 (275.) | |

| Parity (n, %) | p = 0.0638 | ||

| Nulliparity | 1484 (65.6) | 1843 (63.1) | |

| Multiparity | 778 (34.4) | 1077 (36.9) | |

| Gestational weigh gain (mean±SD; Kg) | 13.3±6.0 | 14.2±6.2 | p < 0.0001 |

| Preterm birth (<37th week, n, %) | p < 0.0001 | ||

| No | 1920 (84.9) | 1701 (58.3) | |

| Yes | 342 (15.1) | 1219 (41.7) | |

| Gestational diabetes (n, %) | p = 0.7019 | ||

| No | 2167 (95.8) | 2791 (95.6) | |

| Yes | 95 (4.2) | 129 (4.4) | |

| Pregnancy induced hypertension (n, %) | p = 0.1426 | ||

| No | 2179 (96.3) | 2789 (95.5) | |

| Yes | 83 (3.7) | 131 (4.5) | |

| Exclusive breastfeeding (n, %) | p < 0.0001 | ||

| No | 872 (38.6) | 1736 (59.5) | |

| Yes | 1390 (61.4) | 1184 (40.5) | |

| Hospital type of delivery (n, %) | p = 0.0001 | ||

| Public hospital | 1226 (54.2) | 1296 (44.4) | |

| Private hospital | 1036 (45.8) | 1624 (5.6) | |

| Characteristics | Caesarean section | |

|---|---|---|

| HR* (95% CI**) | p-value | |

| Age (below / over mean value) | 1.58 (1.25-1.91) | p = 0.0048 |

| Nationality (Greek / other) | 0.97 (0.34-1.67) | p= 0.5503 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (underweight or normal / overweight or obese) | 2.14 (1.91-2.40) | p = 0.0008 |

| Education level (below / over mean value) | 1.43 (0.88-1.99) | p = 0.1705 |

| Economic status (low or medium / high) | 1.31 (0.92-1.76) | p = 0.0387 |

| Smoking habits (No / Yes) | 1.72 (1.28-2.38) | p = 0.0412 |

| Parity (Nulliparity / Multiparity) | 1.20 (0.83-1.73) | p = 0.1433 |

| Gestational weigh gain (below / over mean value) | 1.26 (0.96-1.62) | p = 0.0094 |

| Preterm birth (No / Yes) | 1.84 (1.59-2.09) | p=0.0012 |

| Gestational diabetes (No / Yes) | 1.07 (0.23-2.04) | p = 0.8498 |

| Pregnancy induced hypertension (No / Yes) | 1.18 (0.69-1.85) | p = 0.2085 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding (No / Yes) | 0.44 (0.19-0.68) | p = 0.0002 |

| Type of hospital of delivery (public / private) | 2.05 (1.78-2.41) | p = 0.0021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).