Submitted:

28 June 2023

Posted:

29 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Different concepts of Model

2.1. Model:

2.2. Model:

2.3 Model:

2.4 Model:

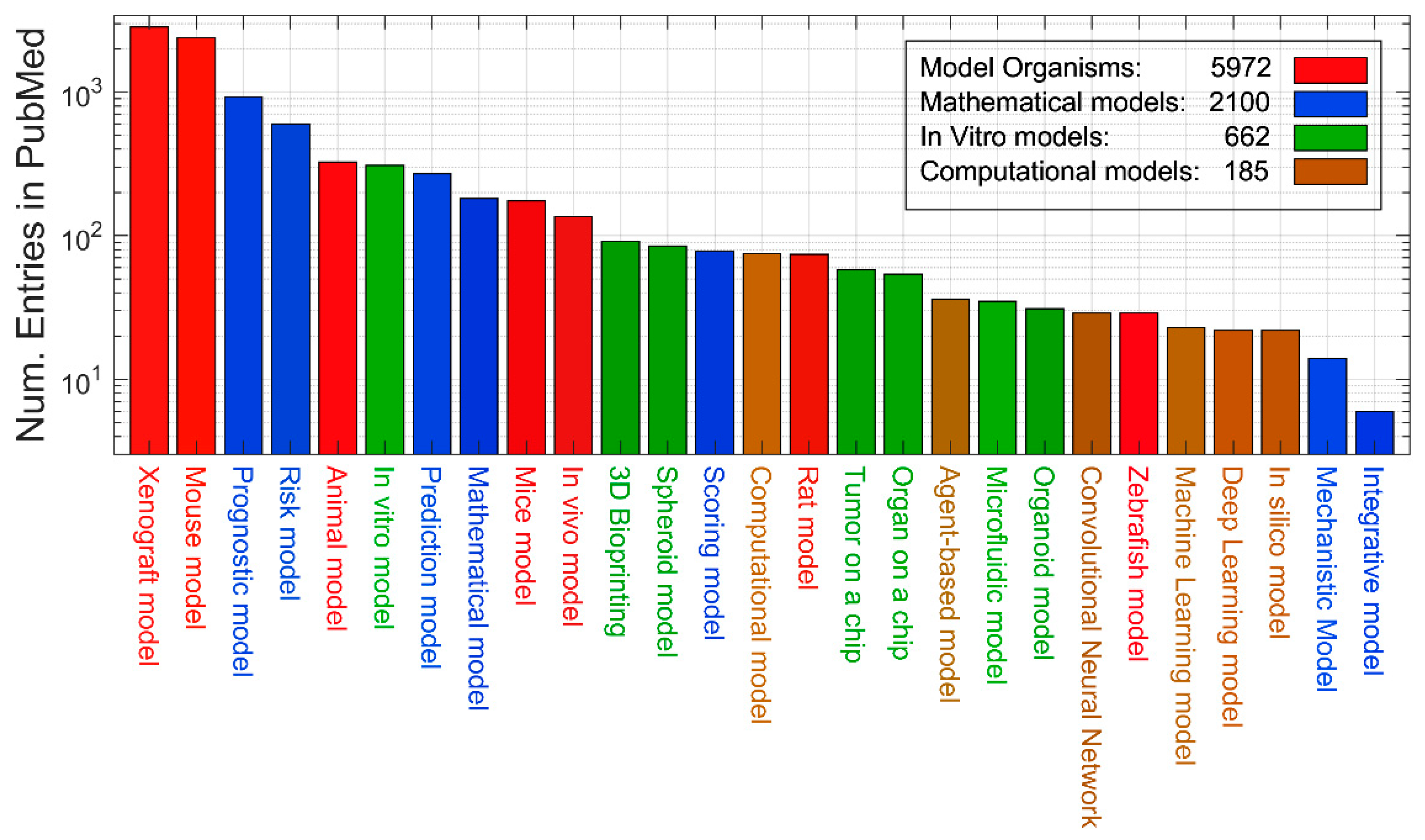

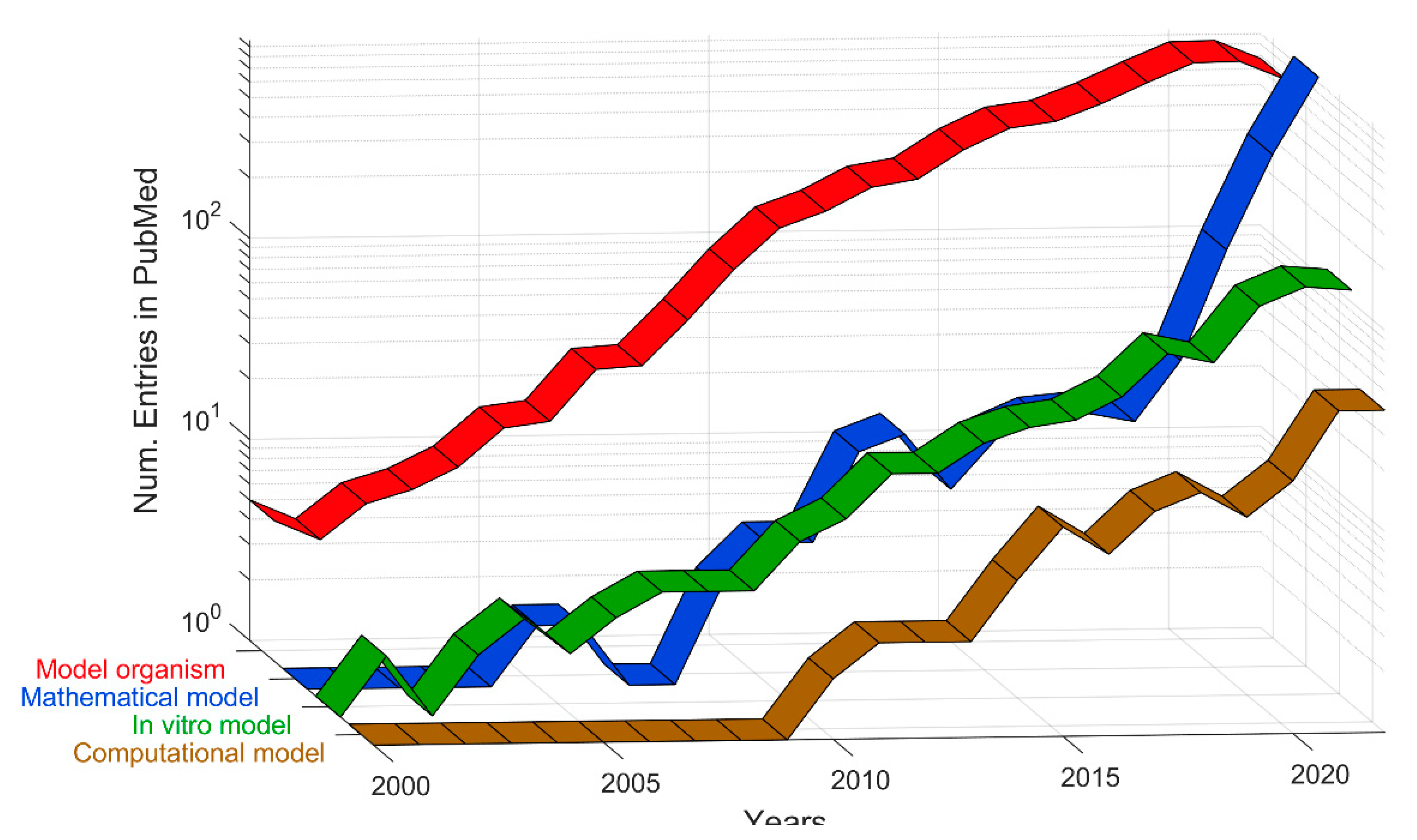

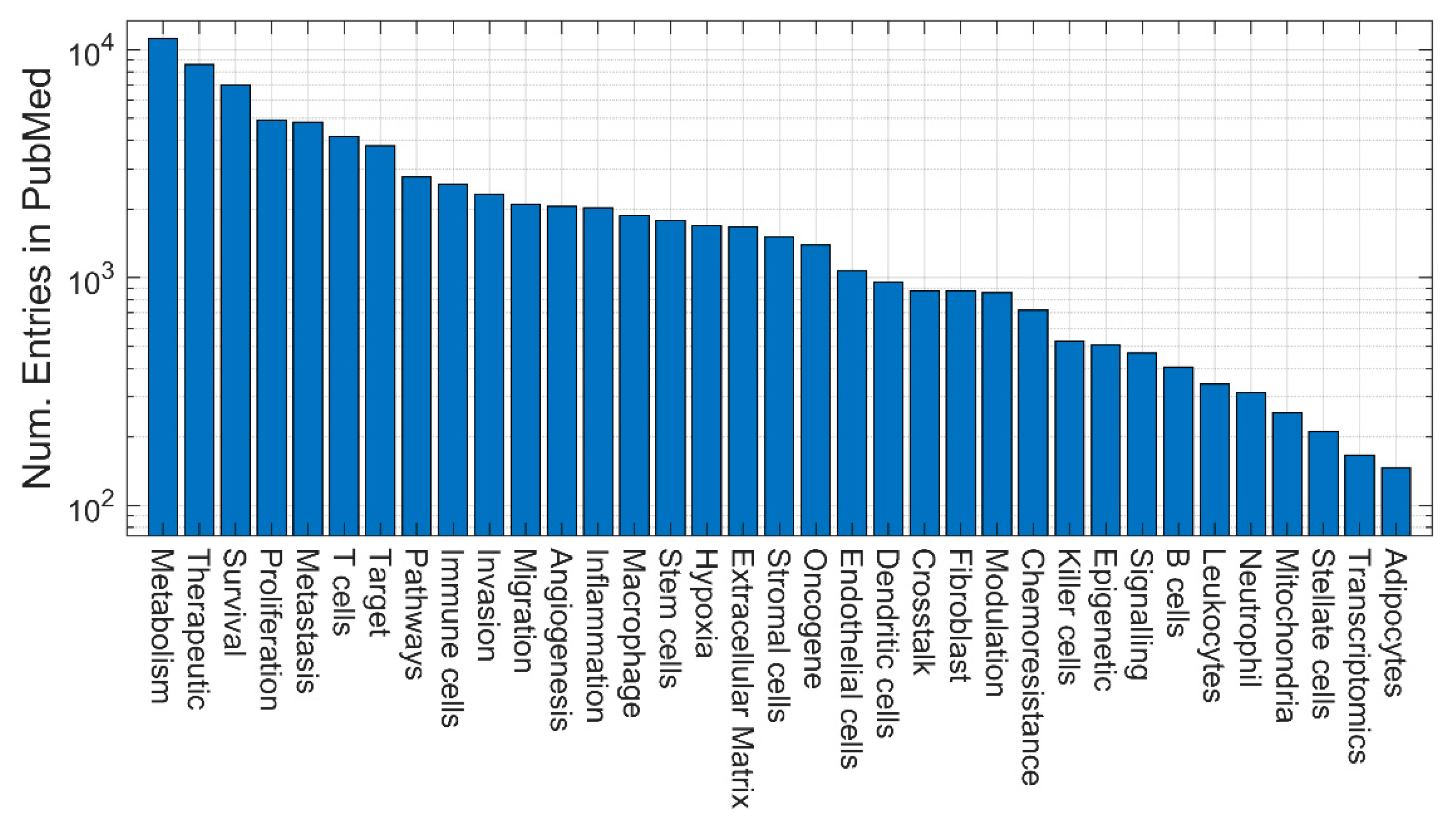

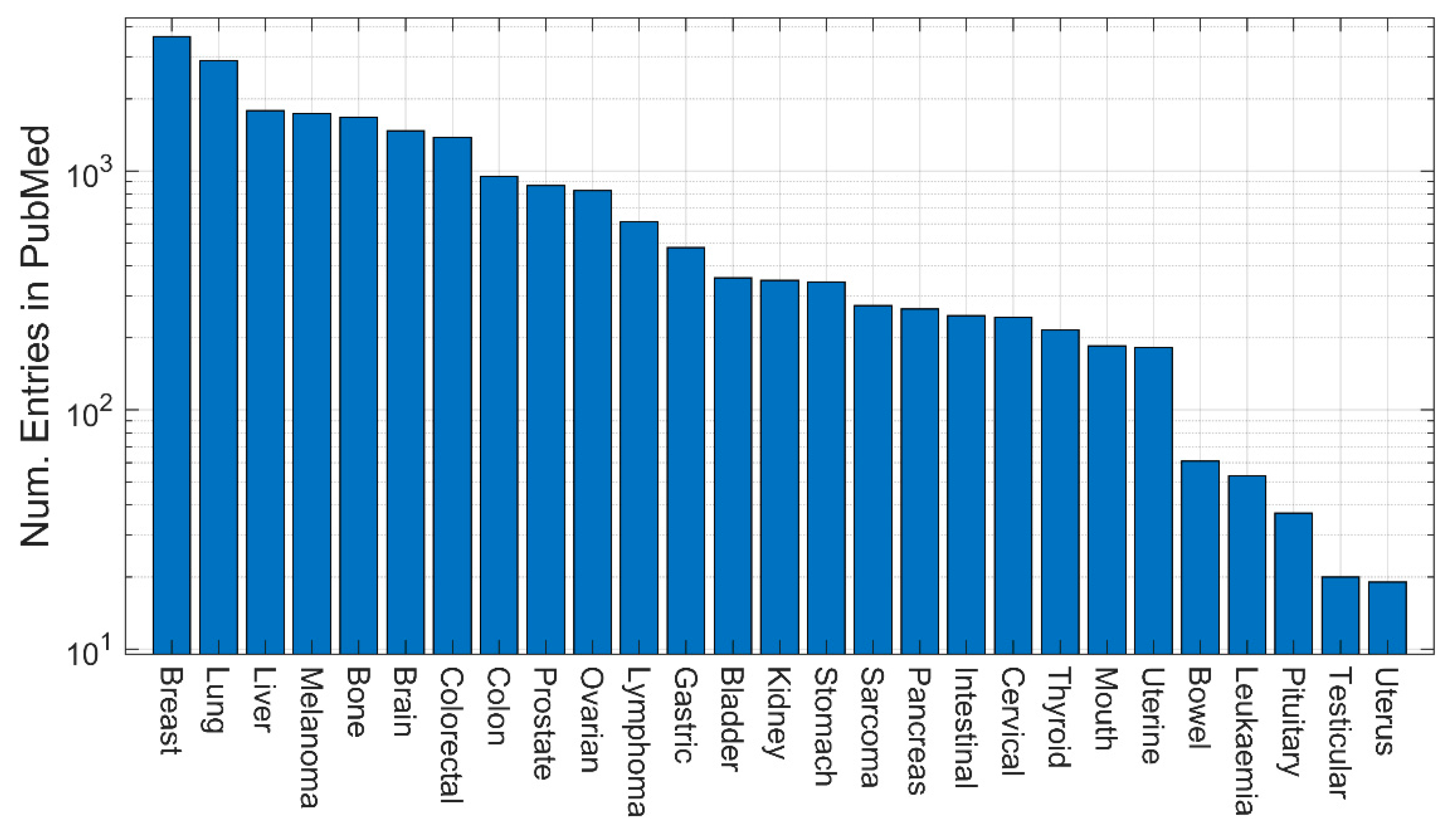

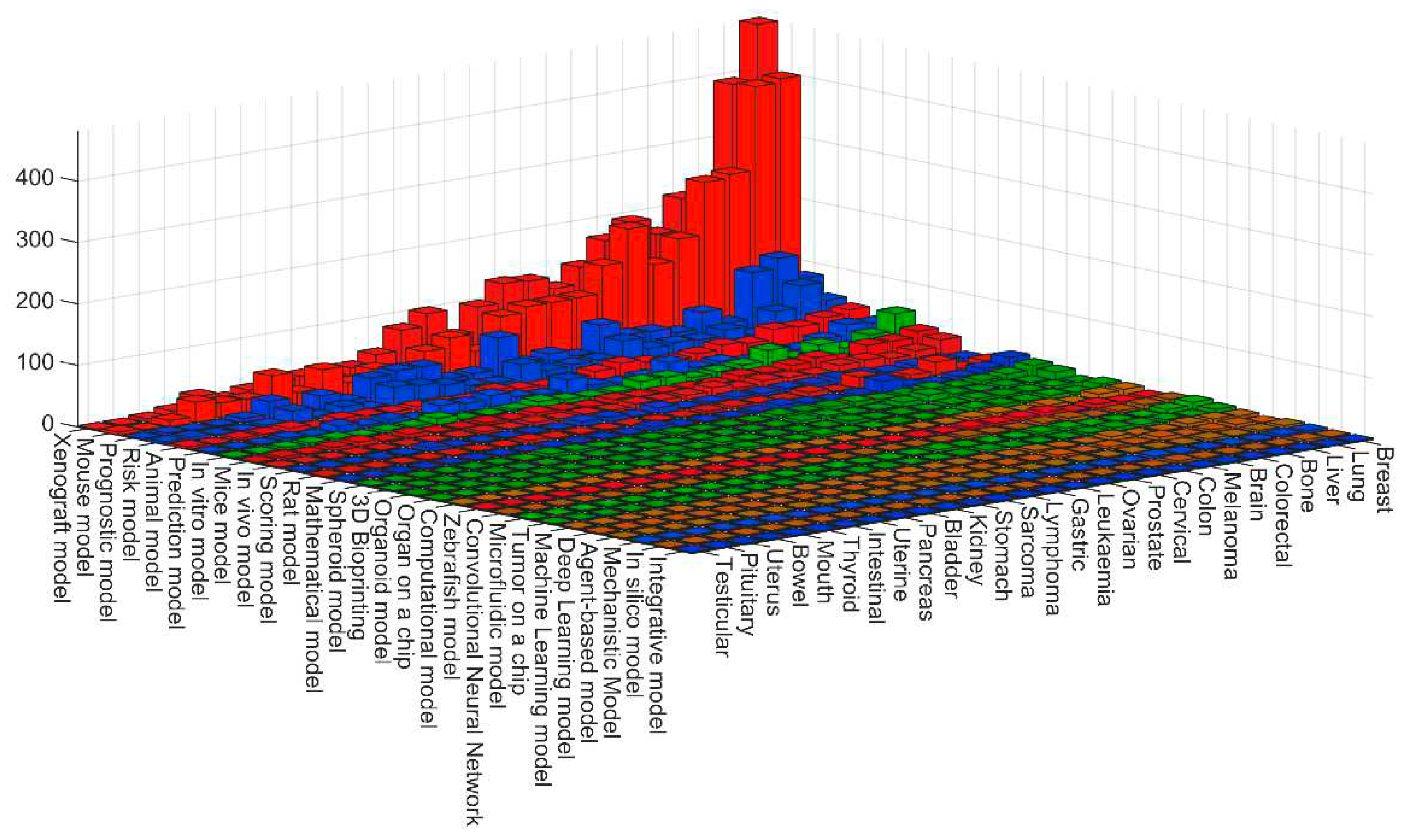

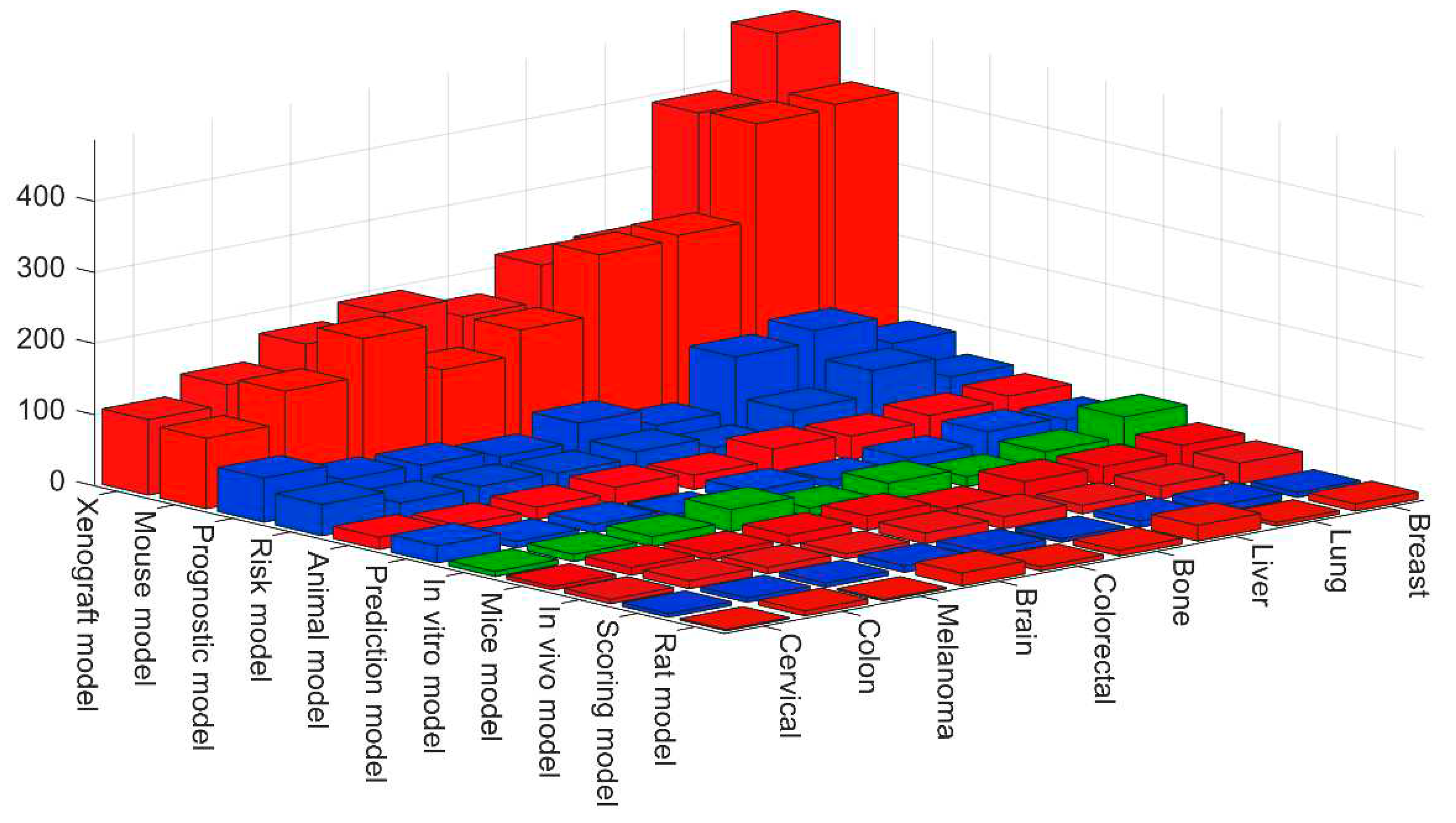

3. Quantitative evaluation of the presence of different models in Medline

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- L. Laplane, D. Duluc, A. Bikfalvi, N. Larmonier, and T. Pradeu, “Beyond the tumour microenvironment,” International Journal of Cancer, vol. 145, no. 10, pp. 2611–2618, 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. R. Balkwill, M. Capasso, and T. Hagemann, “The tumor microenvironment at a glance,” Journal of Cell Science, vol. 125, no. 23, pp. 5591–5596, Dec. 2012. [CrossRef]

- N. M. Anderson and M. C. Simon, “The tumor microenvironment,” Current Biology, vol. 30, no. 16, pp. R921–R925, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xiao and D. Yu, “Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer,” Pharmacol Ther, vol. 221, p. 107753, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Paget, “THE DISTRIBUTION OF SECONDARY GROWTHS IN CANCER OF THE BREAST.,” The Lancet, vol. 133, no. 3421, pp. 571–573, Mar. 1889. [CrossRef]

- M. Akhtar, A. Haider, S. Rashid, and A. D. M. H. Al-Nabet, “Paget’s ‘Seed and Soil’ Theory of Cancer Metastasis: An Idea Whose Time has Come,” Advances in Anatomic Pathology, vol. 26, no. 1, p. 69, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Li et al., “Targeting of tumour-infiltrating macrophages via CCL2/CCR2 signalling as a therapeutic strategy against hepatocellular carcinoma,” Gut, vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 157–167, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. García-Marín et al., “CD8+ Tumour-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Tumour Microenvironment Immune Types as Biomarkers for Immunotherapy in Sinonasal Intestinal-Type Adenocarcinoma,” Vaccines (Basel), vol. 8, no. 2, p. 202, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. a. C. Versluis et al., “The prognostic benefit of tumour-infiltrating Natural Killer cells in endometrial cancer is dependent on concurrent overexpression of Human Leucocyte Antigen-E in the tumour microenvironment,” Eur J Cancer, vol. 86, pp. 285–295, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Ahmed, A. Ghoshal, S. Jones, I. Ellis, and M. Islam, “Head and Neck Cancer Metastasis and the Effect of the Local Soluble Factors, from the Microenvironment, on Signalling Pathways: Is It All about the Akt?,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 12, no. 8, p. 2093, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Akimoto, R. Maruyama, H. Takamaru, T. Ochiya, and K. Takenaga, “Soluble IL-33 receptor sST2 inhibits colorectal cancer malignant growth by modifying the tumour microenvironment,” Nat Commun, vol. 7, p. 13589, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Kupsa, J. Vanek, P. Zak, L. Jebavy, and J. M. Horacek, “Serum levels of selected cytokines and soluble adhesion molecules in acute myeloid leukemia: Soluble receptor for interleukin-2 predicts overall survival,” Cytokine, vol. 128, p. 155005, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Walker, E. Mojares, and A. Del Río Hernández, “Role of Extracellular Matrix in Development and Cancer Progression,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 19, no. 10, p. 3028, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Kolesnikoff, C.-H. Chen, and M. S. Samuel, “Interrelationships between the extracellular matrix and the immune microenvironment that govern epithelial tumour progression,” Clin Sci (Lond), vol. 136, no. 5, pp. 361–377, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Karlsson and H. Nyström, “The extracellular matrix in colorectal cancer and its metastatic settling - Alterations and biological implications,” Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, vol. 175, p. 103712, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. K. Tee et al., “Nanoparticles’ interactions with vasculature in diseases,” Chem Soc Rev, vol. 48, no. 21, pp. 5381–5407, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. H. E. Baker et al., “Targeting the tumour vasculature: exploitation of low oxygenation and sensitivity to NOS inhibition by treatment with a hypoxic cytotoxin,” PLoS One, vol. 8, no. 10, p. e76832, 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Maman and I. P. Witz, “A history of exploring cancer in context,” Nat Rev Cancer, vol. 18, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Leonelli and R. A. Ankeny, “What makes a model organism?,” Endeavour, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 209–212, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Z. D. Blount, “The unexhausted potential of E. coli,” Elife, vol. 4, p. e05826, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Nielsen, “Yeast Systems Biology: Model Organism and Cell Factory,” Biotechnol J, vol. 14, no. 9, p. e1800421, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Renshaw and N. S. Trede, “A model 450 million years in the making: zebrafish and vertebrate immunity,” Dis Model Mech, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 38–47, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- V. Paschall and K. Liu, “An Orthotopic Mouse Model of Spontaneous Breast Cancer Metastasis,” J Vis Exp, no. 114, p. 54040, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- W. Lodge et al., “Tumor-derived MMPs regulate cachexia in a Drosophila cancer model,” Dev Cell, vol. 56, no. 18, pp. 2664-2680.e6, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Vanhooren and C. Libert, “The mouse as a model organism in aging research: usefulness, pitfalls and possibilities,” Ageing Res Rev, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 8–21, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Trammell and A. G. Goodman, “Emerging Mechanisms of Insulin-Mediated Antiviral Immunity in Drosophila melanogaster,” Front Immunol, vol. 10, p. 2973, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Fields and M. Johnston, “Whither Model Organism Research?,” Science, vol. 307, no. 5717, pp. 1885–1886, Mar. 2005. [CrossRef]

- G. Yao et al., “Astragalin attenuates depression-like behaviors and memory deficits and promotes M2 microglia polarization by regulating IL-4R/JAK1/STAT6 signaling pathway in a murine model of perimenopausal depression,” Psychopharmacology (Berl), vol. 239, no. 8, pp. 2421–2443, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Foss et al., “PET/CT imaging of CSF1R in a mouse model of tuberculosis,” Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, vol. 49, no. 12, pp. 4088–4096, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Nong et al., “Single dose of synthetic microRNA-199a or microRNA-149 mimic does not improve cardiac function in a murine model of myocardial infarction,” Mol Cell Biochem, vol. 476, no. 11, pp. 4093–4106, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Stiedl, B. Grabner, K. Zboray, E. Bogner, and E. Casanova, “Modeling cancer using genetically engineered mice,” Methods Mol Biol, vol. 1267, pp. 3–18, 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Entenberg, M. H. Oktay, and J. S. Condeelis, “Intravital imaging to study cancer progression and metastasis,” Nat Rev Cancer, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 25–42, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Thamavit, N. Bhamarapravati, S. Sahaphong, S. Vajrasthira, and S. Angsubhakorn, “Effects of Dimethylnitrosamine on Induction of Cholagiocarcinoma in Opisthorchis viverrini-infected Syrian Golden Hamsters1,” Cancer Research, vol. 38, no. 12, pp. 4634–4639, Dec. 1978.

- R. A. Crallan, N. T. Georgopoulos, and J. Southgate, “Experimental models of human bladder carcinogenesis,” Carcinogenesis, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 374–381, Mar. 2006. [CrossRef]

- M.-B. Hu et al., “Differential expressions of integrin-linked kinase, β-parvin and cofilin 1 in high-fat diet induced prostate cancer progression in a transgenic mouse model,” Oncol Lett, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 4945–4952, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Asgharpour et al., “A diet-induced animal model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular cancer,” J Hepatol, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 579–588, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, X. Liu, L. Gao, and Y. Liu, “Xenograft Mouse Model of Human Uveal Melanoma,” Bio Protoc, vol. 7, no. 21, p. e2594, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- 3A. Fantozzi and G. Christofori, “Mouse models of breast cancer metastasis,” Breast Cancer Research, vol. 8, no. 4, p. 212, 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. Yang, J. J. Zhang, and X.-Y. Huang, “Mouse models for tumor metastasis,” Methods Mol Biol, vol. 928, pp. 221–228, 2012. [CrossRef]

- E. E. Patton et al., “Melanoma models for the next generation of therapies,” Cancer Cell, vol. 39, no. 5, pp. 610–631, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Piskovatska, O. Strilbytska, A. Koliada, A. Vaiserman, and O. Lushchak, “Health Benefits of Anti-aging Drugs,” Subcell Biochem, vol. 91, pp. 339–392, 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Loeuillard, S. R. Fischbach, G. J. Gores, and S. Rizvi, “Animal models of cholangiocarcinoma,” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease, vol. 1865, no. 5, pp. 982–992, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Seok et al., “Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 110, no. 9, pp. 3507–3512, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. B. van der Worp et al., “Can Animal Models of Disease Reliably Inform Human Studies?,” PLOS Medicine, vol. 7, no. 3, p. e1000245, Mar. 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. Chung, D. Nasralla, and A. Quaglia, “Understanding the Immunoenvironment of Primary Liver Cancer: A Histopathology Perspective,” J Hepatocell Carcinoma, vol. 9, pp. 1149–1169, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Lendvai et al., “Cholangiocarcinoma: Classification, Histopathology and Molecular Carcinogenesis,” Pathol Oncol Res, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 3–15, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Mungenast et al., “Next-Generation Digital Histopathology of the Tumor Microenvironment,” Genes, vol. 12, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Jia et al., “Multiplex immunohistochemistry defines the tumor immune microenvironment and immunotherapeutic outcome in CLDN18.2-positive gastric cancer,” BMC Med, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 223, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Ahn et al., “Plasmablastic Lymphomas: Characterization of Tumor Microenvironment Using CD163 and PD-1 Immunohistochemistry,” Ann Clin Lab Sci, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 213–218, Mar. 2020.

- H. D. Papenfuss, J. F. Gross, M. Intaglietta, and F. A. Treese, “A transparent access chamber for the rat dorsal skin fold,” Microvasc Res, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 311–318, Nov. 1979. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Lunt, C. Gray, C. C. Reyes-Aldasoro, S. J. Matcher, and G. M. Tozer, “Application of intravital microscopy in studies of tumor microcirculation,” J Biomed Opt, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 011113, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Akerman et al., “Influence of soluble or matrix-bound isoforms of vascular endothelial growth factor-A on tumor response to vascular-targeted strategies,” Int J Cancer, vol. 133, no. 11, pp. 2563–2576, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. C. Reyes-Aldasoro et al., “Estimation of apparent tumor vascular permeability from multiphoton fluorescence microscopic images of P22 rat sarcomas in vivo,” Microcirculation, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 65–79, Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Prasad et al., “Optical and magnetic resonance imaging approaches for investigating the tumour microenvironment: state-of-the-art review and future trends,” Nanotechnology, vol. 32, no. 6, p. 062001, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Matsuo, S. Matsumoto, J. B. Mitchell, M. C. Krishna, and K. Camphausen, “Magnetic resonance imaging of the tumor microenvironment in radiotherapy: perfusion, hypoxia, and metabolism,” Semin Radiat Oncol, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 210–217, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. Zinnhardt et al., “Imaging of the glioma microenvironment by TSPO PET,” Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 174–185, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. M. L. Lilburn and A. M. Groves, “The role of PET in imaging of the tumour microenvironment and response to immunotherapy,” Clin Radiol, vol. 76, no. 10, p. 784.e1-784.e15, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Lambert, “COMPARATIVE STUDIES UPON CANCER CELLS AND NORMAL CELLS : II. THE CHARACTER OF GROWTH IN VITRO WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO CELL DIVISION,” J Exp Med, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 499–510, May 1913. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Eichorn, K. V. Huffman, J. J. Oleson, S. L. Halliday, and J. H. Williams, “A Comparison of in Vivo and in Vitro Tests for Antineoplastic Activity of Eight Compounds,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 58, no. 7, pp. 1172–1182, 1954. [CrossRef]

- D. Tuveson and H. Clevers, “Cancer modeling meets human organoid technology,” Science, vol. 364, no. 6444, pp. 952–955, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Baker, S. Shabir, and J. Southgate, “Biomimetic Urothelial Tissue Models for the in Vitro Evaluation of Barrier Physiology and Bladder Drug Efficacy,” Mol. Pharmaceutics, vol. 11, no. 7, pp. 1964–1970, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Pound and M. Ritskes-Hoitinga, “Is it possible to overcome issues of external validity in preclinical animal research? Why most animal models are bound to fail,” Journal of Translational Medicine, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 304, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Musa, D. Ouaret, and W. F. Bodmer, “In Vitro Analyses of Interactions Between Colonic Myofibroblasts and Colorectal Cancer Cells for Anticancer Study,” Anticancer Res, vol. 40, no. 11, pp. 6063–6073, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Alhussan et al., “Potential of Gold Nanoparticle in Current Radiotherapy Using a Co-Culture Model of Cancer Cells and Cancer Associated Fibroblast Cells,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 15, p. 3586, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Hamilton et al., “Mimicking the tumour microenvironment: three different co-culture systems induce a similar phenotype but distinct proliferative signals in primary chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells,” Br J Haematol, vol. 158, no. 5, pp. 589–599, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Xu and F. M. Richards, “Development of In Vitro Co-Culture Model in Anti-Cancer Drug Development Cascade,” Comb Chem High Throughput Screen, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 451–457, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Curtis et al., “Fibroblasts Mobilize Tumor Cell Glycogen to Promote Proliferation and Metastasis,” Cell Metab, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 141-155.e9, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Erdogan et al., “Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote directional cancer cell migration by aligning fibronectin,” J Cell Biol, vol. 216, no. 11, pp. 3799–3816, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Kanthou et al., “Tumour cells expressing single VEGF isoforms display distinct growth, survival and migration characteristics,” PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 8, p. e104015, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Wen et al., “Cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF)-derived IL32 promotes breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis via integrin β3-p38 MAPK signalling,” Cancer Lett, vol. 442, pp. 320–332, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Kikuchi, D. Koyama, H. Y. Mukai, and Y. Furukawa, “Suitable drug combination with bortezomib for multiple myeloma under stroma-free conditions and in contact with fibronectin or bone marrow stromal cells,” Int J Hematol, vol. 99, no. 6, pp. 726–736, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Lunt et al., “Vascular effects dominate solid tumor response to treatment with combretastatin A-4-phosphate,” Int J Cancer, vol. 129, no. 8, pp. 1979–1989, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Kapałczyńska et al., “2D and 3D cell cultures – a comparison of different types of cancer cell cultures,” Arch Med Sci, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 910–919, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Ellem, E. M. De-Juan-Pardo, and G. P. Risbridger, “In vitro modeling of the prostate cancer microenvironment,” Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, vol. 79–80, pp. 214–221, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Huerta-Reyes and A. Aguilar-Rojas, “Three-dimensional models to study breast cancer (Review),” Int J Oncol, vol. 58, no. 3, pp. 331–343, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Bär, B. Biersack, and R. Schobert, “3D cell cultures, as a surrogate for animal models, enhance the diagnostic value of preclinical in vitro investigations by adding information on the tumour microenvironment: a comparative study of new dual-mode HDAC inhibitors,” Invest New Drugs, vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 953–961, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Kunz-Schughart, M. Kreutz, and R. Knuechel, “Multicellular spheroids: a three-dimensional in vitro culture system to study tumour biology,” Int J Exp Pathol, vol. 79, no. 1, pp. 1–23, Feb. 1998. [CrossRef]

- S. Gunti, A. T. K. Hoke, K. P. Vu, and N. R. London, “Organoid and Spheroid Tumor Models: Techniques and Applications,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 13, no. 4, p. 874, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Xia, W.-L. Du, X.-Y. Chen, and Y.-N. Zhang, “Organoid models of the tumor microenvironment and their applications,” J Cell Mol Med, vol. 25, no. 13, pp. 5829–5841, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Rizzo et al., “A pH-sensor scaffold for mapping spatiotemporal gradients in three-dimensional in vitro tumour models,” Biosens Bioelectron, vol. 212, p. 114401, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Mazzoleni, D. Di Lorenzo, and N. Steimberg, “Modelling tissues in 3D: the next future of pharmaco-toxicology and food research?,” Genes Nutr, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 13–22, Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- L. Neufeld, E. Yeini, S. Pozzi, and R. Satchi-Fainaro, “3D bioprinted cancer models: from basic biology to drug development,” Nat Rev Cancer, vol. 22, no. 12, Art. no. 12, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Leek, D. R. Grimes, A. L. Harris, and A. McIntyre, “Methods: Using Three-Dimensional Culture (Spheroids) as an In Vitro Model of Tumour Hypoxia,” Adv Exp Med Biol, vol. 899, pp. 167–196, 2016. [CrossRef]

- I. Manini et al., “Role of Microenvironment in Glioma Invasion: What We Learned from In Vitro Models,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 147, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H.-F. Tsai, A. Trubelja, A. Q. Shen, and G. Bao, “Tumour-on-a-chip: microfluidic models of tumour morphology, growth and microenvironment,” J R Soc Interface, vol. 14, no. 131, p. 20170137, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Nolan, O. M. T. Pearce, H. R. C. Screen, M. M. Knight, and S. W. Verbruggen, “Organ-on-a-Chip and Microfluidic Platforms for Oncology in the UK,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 3, p. 635, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Ozcelikkale, H.-R. Moon, M. Linnes, and B. Han, “In vitro microfluidic models of tumor microenvironment to screen transport of drugs and nanoparticles,” Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol, vol. 9, no. 5, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Kundu, D. Caballero, C. M. Abreu, R. L. Reis, and S. C. Kundu, “The Tumor Microenvironment: An Introduction to the Development of Microfluidic Devices,” Adv Exp Med Biol, vol. 1379, pp. 115–138, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Byrne, “Dissecting cancer through mathematics: from the cell to the animal model,” Nat Rev Cancer, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 221–230, Mar. 2010. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Altrock, L. L. Liu, and F. Michor, “The mathematics of cancer: integrating quantitative models,” Nat Rev Cancer, vol. 15, no. 12, pp. 730–745, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. R. Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population: Or, A View of Its Past and Present Effects on Human Happiness. J. Johnson, 1807.

- P. Armitage and R. Doll, “The Age Distribution of Cancer and a Multi-stage Theory of Carcinogenesis,” Br J Cancer, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Mar. 1954.

- T. G. Clark, M. J. Bradburn, S. B. Love, and D. G. Altman, “Survival Analysis Part I: Basic concepts and first analyses,” Br J Cancer, vol. 89, no. 2, pp. 232–238, Jul. 2003. [CrossRef]

- J. Fan and Z. Yu, “A univariate model of calcium release in the dyadic cleft of cardiac myocytes,” Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, vol. 2009, pp. 4499–4503, 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. Bradburn, T. G. Clark, S. B. Love, and D. G. Altman, “Survival Analysis Part II: Multivariate data analysis – an introduction to concepts and methods,” Br J Cancer, vol. 89, no. 3, pp. 431–436, Aug. 2003. [CrossRef]

- K. Azuma et al., “Clinical significance of plasma-free amino acids and tryptophan metabolites in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving PD-1 inhibitor: a pilot cohort study for developing a prognostic multivariate model,” J Immunother Cancer, vol. 10, no. 5, p. e004420, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Beckman, I. Kareva, and F. R. Adler, “How Should Cancer Models Be Constructed?,” Cancer Control, vol. 27, no. 1, p. 1073274820962008, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Anderson and V. Quaranta, “Integrative mathematical oncology,” Nat Rev Cancer, vol. 8, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- L. Curtin, A. Hawkins-Daarud, A. B. Porter, K. G. van der Zee, M. R. Owen, and K. R. Swanson, “A Mechanistic Investigation into Ischemia-Driven Distal Recurrence of Glioblastoma,” Bull Math Biol, vol. 82, no. 11, p. 143, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. R. Menon and M. Fujita, “A state of stochastic cancer stemness through the CDK1-SOX2 axis,” Oncotarget, vol. 10, no. 27, pp. 2583–2585, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Kumar, G. M. Cramer, S. A. Z. Dahaj, B. Sundaram, J. P. Celli, and R. V. Kulkarni, “Stochastic modeling of phenotypic switching and chemoresistance in cancer cell populations,” Sci Rep, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 10845, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Gommes, T. Louis, I. Bourgot, A. Noël, S. Blacher, and E. Maquoi, “Remodelling of the fibre-aggregate structure of collagen gels by cancer-associated fibroblasts: A time-resolved grey-tone image analysis based on stochastic modelling,” Front Immunol, vol. 13, p. 988502, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Morales and L. Soto-Ortiz, “Modeling Macrophage Polarization and Its Effect on Cancer Treatment Success,” Open J Immunol, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 36–80, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Blaszczak and P. Swietach, “What do cellular responses to acidity tell us about cancer?,” Cancer Metastasis Rev, vol. 40, no. 4, pp. 1159–1176, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Belfatto et al., “Comparison between model-predicted tumor oxygenation dynamics and vascular-/flow-related Doppler indices,” Med Phys, vol. 44, no. 5, pp. 2011–2019, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Possenti et al., “A Mesoscale Computational Model for Microvascular Oxygen Transfer,” Ann Biomed Eng, vol. 49, no. 12, pp. 3356–3373, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Zhang, L. X. Xu, G. A. Sandison, and J. Zhang, “A microscale model for prediction of breast cancer cell damage during cryosurgery,” Cryobiology, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 143–154, Oct. 2003. [CrossRef]

- D. Noble, “Modeling the heart--from genes to cells to the whole organ,” Science, vol. 295, no. 5560, pp. 1678–1682, Mar. 2002. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, Y. Cai, Q. Chen, and Z. Li, “Multiscale modeling of solid stress and tumor cell invasion in response to dynamic mechanical microenvironment,” Biomech Model Mechanobiol, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 577–590, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Sadhukhan, P. K. Mishra, S. K. Basu, and J. K. Mandal, “A multi-scale agent-based model for avascular tumour growth,” Biosystems, vol. 206, p. 104450, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, J. D. Butner, R. Kerketta, V. Cristini, and T. S. Deisboeck, “Simulating cancer growth with multiscale agent-based modeling,” Seminars in Cancer Biology, vol. 30, pp. 70–78, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. Gerlee, E. Kim, and A. R. A. Anderson, “Bridging scales in cancer progression: Mapping genotype to phenotype using neural networks,” Seminars in Cancer Biology, vol. 30, pp. 30–41, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Wijeratne et al., “Multiscale modelling of solid tumour growth: the effect of collagen micromechanics,” Biomech Model Mechanobiol, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 1079–1090, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. Kumar, J. Li, and C. Surulescu, “Multiscale modeling of glioma pseudopalisades: contributions from the tumor microenvironment,” J Math Biol, vol. 82, no. 6, p. 49, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. G. Powathil, M. Swat, and M. A. J. Chaplain, “Systems oncology: towards patient-specific treatment regimes informed by multiscale mathematical modelling,” Semin. Cancer Biol., vol. 30, pp. 13–20, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Nikmaneshi and B. Firoozabadi, “Investigation of cancer response to chemotherapy: a hybrid multi-scale mathematical and computational model of the tumor microenvironment,” Biomech Model Mechanobiol, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 1233–1249, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Peng, D. Trucu, P. Lin, A. Thompson, and M. A. J. Chaplain, “A Multiscale Mathematical Model of Tumour Invasive Growth,” Bull Math Biol, vol. 79, no. 3, pp. 389–429, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Chowkwale, G. J. Mahler, P. Huang, and B. T. Murray, “A multiscale in silico model of endothelial to mesenchymal transformation in a tumor microenvironment,” J Theor Biol, vol. 480, pp. 229–240, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Pourhasanzade and S. H. Sabzpoushan, “A New Mathematical Model for Controlling Tumor Growth Based on Microenvironment Acidity and Oxygen Concentration,” Biomed Res Int, vol. 2021, p. 8886050, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. H. W. J. ten Tusscher, D. Noble, P. J. Noble, and A. V. Panfilov, “A model for human ventricular tissue,” Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, vol. 286, no. 4, pp. H1573-1589, Apr. 2004. [CrossRef]

- K.-A. Norton, C. Gong, S. Jamalian, and A. S. Popel, “Multiscale Agent-Based and Hybrid Modeling of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment,” Processes (Basel), vol. 7, no. 1, p. 37, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Walker and J. Southgate, “The virtual cell--a candidate co-ordinator for ‘middle-out’ modelling of biological systems,” Brief Bioinform, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 450–461, Jul. 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. Walker, S. Wood, J. Southgate, M. Holcombe, and R. Smallwood, “An integrated agent-mathematical model of the effect of intercellular signalling via the epidermal growth factor receptor on cell proliferation,” J Theor Biol, vol. 242, no. 3, pp. 774–789, Oct. 2006. [CrossRef]

- A. Rojas-Domínguez, R. Arroyo-Duarte, F. Rincón-Vieyra, and M. Alvarado-Mentado, “Modeling cancer immunoediting in tumor microenvironment with system characterization through the ising-model Hamiltonian,” BMC Bioinformatics, vol. 23, p. 200, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Rahbar et al., “Agent-based Modeling of Tumor and Immune System Interactions in Combinational Therapy with Low-dose 5-fluorouracil and Dendritic Cell Vaccine in Melanoma B16F10,” Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 151–166, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Cesaro et al., “MAST: a hybrid Multi-Agent Spatio-Temporal model of tumor microenvironment informed using a data-driven approach,” Bioinform Adv, vol. 2, no. 1, p. vbac092, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Tylutki, S. Polak, and B. Wiśniowska, “Top-down, Bottom-up and Middle-out Strategies for Drug Cardiac Safety Assessment via Modeling and Simulations,” Curr Pharmacol Rep, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 171–177, 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. Tsirvouli, V. Touré, B. Niederdorfer, M. Vázquez, Å. Flobak, and M. Kuiper, “A Middle-Out Modeling Strategy to Extend a Colon Cancer Logical Model Improves Drug Synergy Predictions in Epithelial-Derived Cancer Cell Lines,” Front Mol Biosci, vol. 7, p. 502573, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Sugano, “Lost in modelling and simulation?,” ADMET DMPK, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 75–109, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Secomb and A. R. Pries, “The microcirculation: physiology at the mesoscale,” J Physiol, vol. 589, no. Pt 5, pp. 1047–1052, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Korolev, J. B. Xavier, and J. Gore, “Turning ecology and evolution against cancer,” Nat Rev Cancer, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 371–380, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Dujon et al., “Identifying key questions in the ecology and evolution of cancer,” Evol Appl, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 877–892, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Bukkuri et al., “Modeling cancer’s ecological and evolutionary dynamics,” Med Oncol, vol. 40, no. 4, p. 109, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Morris et al., “Identifying the spatial and temporal dynamics of molecularly-distinct glioblastoma sub-populations,” Math Biosci Eng, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 4905–4941, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Antal and P. L. Krapivsky, “Exact solution of a two-type branching process: models of tumor progression,” J. Stat. Mech., vol. 2011, no. 08, p. P08018, Aug. 2011. [CrossRef]

- I. Bozic et al., “Accumulation of driver and passenger mutations during tumor progression,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 107, no. 43, pp. 18545–18550, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- D. Lewin, B. Avignon, A. Tovaglieri, L. Cabon, N. Gjorevski, and L. G. Hutchinson, “An in silico Model of T Cell Infiltration Dynamics Based on an Advanced in vitro System to Enhance Preclinical Decision Making in Cancer Immunotherapy,” Front Pharmacol, vol. 13, p. 837261, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Curtin, A. Hawkins-Daarud, K. G. van der Zee, K. R. Swanson, and M. R. Owen, “Speed Switch in Glioblastoma Growth Rate due to Enhanced Hypoxia-Induced Migration,” Bull Math Biol, vol. 82, no. 3, p. 43, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. de Melo Quintela, S. Hervas-Raluy, J. M. Garcia-Aznar, D. Walker, K. Y. Wertheim, and M. Viceconti, “A theoretical analysis of the scale separation in a model to predict solid tumour growth,” J Theor Biol, vol. 547, p. 111173, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Anderson, “A Hybrid Multiscale Model of Solid Tumour Growth and Invasion: Evolution and the Microenvironment,” in Single-Cell-Based Models in Biology and Medicine, A. R. A. Anderson, M. A. J. Chaplain, and K. A. Rejniak, Eds., in Mathematics and Biosciences in Interaction. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2007, pp. 3–28. [CrossRef]

- M. a. J. Chaplain, S. R. McDougall, and A. R. A. Anderson, “Mathematical modeling of tumor-induced angiogenesis,” Annu Rev Biomed Eng, vol. 8, pp. 233–257, 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Chaplain, S. M. Giles, B. D. Sleeman, and R. J. Jarvis, “A mathematical analysis of a model for tumour angiogenesis,” J Math Biol, vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 744–770, 1995. [CrossRef]

- H. Enderling, M. A. J. Chaplain, A. R. A. Anderson, and J. S. Vaidya, “A mathematical model of breast cancer development, local treatment and recurrence,” J Theor Biol, vol. 246, no. 2, pp. 245–259, May 2007. [CrossRef]

- I. Ramis-Conde, M. A. J. Chaplain, A. R. A. Anderson, and D. Drasdo, “Multi-scale modelling of cancer cell intravasation: the role of cadherins in metastasis,” Phys Biol, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 016008, Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- B. D. Sleeman and H. R. Nimmo, “Fluid transport in vascularized tumours and metastasis,” IMA J Math Appl Med Biol, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 53–63, Mar. 1998.

- M. R. Owen, H. M. Byrne, and C. E. Lewis, “Mathematical modelling of the use of macrophages as vehicles for drug delivery to hypoxic tumour sites,” J Theor Biol, vol. 226, no. 4, pp. 377–391, Feb. 2004. [CrossRef]

- T. D. Lewin, H. M. Byrne, P. K. Maini, J. J. Caudell, E. G. Moros, and H. Enderling, “The importance of dead material within a tumour on the dynamics in response to radiotherapy,” Phys Med Biol, vol. 65, no. 1, p. 015007, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Italia, K. Y. Wertheim, S. Taschner-Mandl, D. Walker, and F. Dercole, “Mathematical Model of Clonal Evolution Proposes a Personalised Multi-Modal Therapy for High-Risk Neuroblastoma,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 7, p. 1986, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Araujo, L. M. Cook, C. C. Lynch, and D. Basanta, “An integrated computational model of the bone microenvironment in bone-metastatic prostate cancer,” Cancer Res, vol. 74, no. 9, pp. 2391–2401, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Clarke and J. Fisher, “Executable cancer models: successes and challenges,” Nat Rev Cancer, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 343–354, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- I. Myung, Y. Tang, and M. A. Pitt, “Chapter 11 Evaluation and Comparison of Computational Models,” in Methods in Enzymology, in Computer Methods, Part A, vol. 454. Academic Press, 2009, pp. 287–304. [CrossRef]

- B. Goldstein, J. R. Faeder, and W. S. Hlavacek, “Mathematical and computational models of immune-receptor signalling,” Nat Rev Immunol, vol. 4, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jun. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ji, K. Yan, W. Li, H. Hu, and X. Zhu, “Mathematical and Computational Modeling in Complex Biological Systems,” BioMed Research International, vol. 2017, p. e5958321, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Konstorum, A. T. Vella, A. J. Adler, and R. C. Laubenbacher, “Addressing current challenges in cancer immunotherapy with mathematical and computational modelling,” Journal of The Royal Society Interface, vol. 14, no. 131, p. 20170150, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. Garcia, S. Bonhoeffer, and F. Fu, “Cancer-induced immunosuppression can enable effectiveness of immunotherapy through bistability generation: A mathematical and computational examination,” J Theor Biol, vol. 492, p. 110185, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Vega, M. Carretero, R. D. M. Travasso, and L. L. Bonilla, “Notch signaling and taxis mechanisms regulate early stage angiogenesis: A mathematical and computational model,” PLoS Comput Biol, vol. 16, no. 1, p. e1006919, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. West, M. Robertson-Tessi, and A. R. A. Anderson, “Agent-based methods facilitate integrative science in cancer,” Trends Cell Biol, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 300–311, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Metzcar, Y. Wang, R. Heiland, and P. Macklin, “A Review of Cell-Based Computational Modeling in Cancer Biology,” JCO Clin Cancer Inform, vol. 3, pp. 1–13, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Homeyer et al., “Automated quantification of steatosis: agreement with stereological point counting,” Diagnostic Pathology, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 80, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Dawood, K. Branson, N. M. Rajpoot, and F. ul A. A. Minhas, “All You Need is Color: Image Based Spatial Gene Expression Prediction Using Neural Stain Learning,” in Machine Learning and Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases, M. Kamp, I. Koprinska, A. Bibal, T. Bouadi, B. Frénay, L. Galárraga, J. Oramas, L. Adilova, G. Graça, et al., Eds., in Communications in Computer and Information Science. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021, pp. 437–450. [CrossRef]

- A. Ortega-Ruiz, C. Karabağ, V. G. Garduño, and C. C. Reyes-Aldasoro, “Morphological Estimation of Cellularity on Neo-Adjuvant Treated Breast Cancer Histological Images,” Journal of Imaging, vol. 6, no. 10, p. 101, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Serin, M. Erturkler, and M. Gul, “A novel overlapped nuclei splitting algorithm for histopathological images,” Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, vol. 151, pp. 57–70, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. W. Sullivan, S. Ghosh, I. T. Ocal, R. L. Camp, D. L. Rimm, and G. G. Chung, “Microvessel area using automated image analysis is reproducible and is associated with prognosis in breast cancer,” Human Pathology, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 156–165, Feb. 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. S. Patlak, R. G. Blasberg, and J. D. Fenstermacher, “Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data,” J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–7, Mar. 1983. [CrossRef]

- C. C. Reyes-Aldasoro, S. Akerman, and G. M. Tozer, “Measuring the velocity of fluorescently labelled red blood cells with a keyhole tracking algorithm,” J Microsc, vol. 229, no. Pt 1, pp. 162–173, Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yuan, “Spatial Heterogeneity in the Tumor Microenvironment,” Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, vol. 6, no. 8, p. a026583, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. McCULLOCH and W. Pitts, “The statistical organization of nervous activity,” Biometrics, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 91–99, Jun. 1948.

- P. beim Graben and J. Wright, “From McCulloch-Pitts neurons toward biology,” Bull Math Biol, vol. 73, no. 2, pp. 261–265, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- K. Simonyan and A. Zisserman, “Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition.” arXiv, Apr. 10, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and G. E. Hinton, “ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks,” Commun. ACM, vol. 60, no. 6, pp. 84–90, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- O. Ronneberger, P. Fischer, and T. Brox, “U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation,” arXiv:1505.04597 [cs], May 2015, Accessed: Mar. 25, 2021. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1505.04597.

- C. Szegedy et al., “Going deeper with convolutions,” in 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Jun. 2015, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Y. LeCun, Y. Bengio, and G. Hinton, “Deep learning,” Nature, vol. 521, no. 7553, Art. no. 7553, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- N. Kriegeskorte and T. Golan, “Neural network models and deep learning,” Current Biology, vol. 29, no. 7, pp. R231–R236, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Kuntz et al., “Gastrointestinal cancer classification and prognostication from histology using deep learning: Systematic review,” Eur J Cancer, vol. 155, pp. 200–215, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Davri et al., “Deep Learning on Histopathological Images for Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis: A Systematic Review,” Diagnostics, vol. 12, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Tran, O. Kondrashova, A. Bradley, E. D. Williams, J. V. Pearson, and N. Waddell, “Deep learning in cancer diagnosis, prognosis and treatment selection,” Genome Med, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 152, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Bhinder, C. Gilvary, N. S. Madhukar, and O. Elemento, “Artificial Intelligence in Cancer Research and Precision Medicine,” Cancer Discov, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 900–915, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu and D. Lin, “A Review of Artificial Intelligence in Precise Assessment of Programmed Cell Death-ligand 1 and Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocytes in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer,” Adv Anat Pathol, vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 439–445, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Thakur, H. Yoon, and Y. Chong, “Current Trends of Artificial Intelligence for Colorectal Cancer Pathology Image Analysis: A Systematic Review,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 12, no. 7, p. 1884, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. E. Bejnordi et al., “Using deep convolutional neural networks to identify and classify tumor-associated stroma in diagnostic breast biopsies,” Modern Pathology, vol. 31, no. 10, pp. 1502–1512, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Pantanowitz et al., “An artificial intelligence algorithm for prostate cancer diagnosis in whole slide images of core needle biopsies: a blinded clinical validation and deployment study,” The Lancet Digital Health, vol. 2, no. 8, pp. e407–e416, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. N. Kather et al., “Predicting survival from colorectal cancer histology slides using deep learning: A retrospective multicenter study,” PLOS Medicine, vol. 16, no. 1, p. e1002730, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Shaban et al., “A digital score of tumour-associated stroma infiltrating lymphocytes predicts survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma,” J Pathol, vol. 256, no. 2, pp. 174–185, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Huang, Z. Liu, L. van der Maaten, and K. Q. Weinberger, “Densely Connected Convolutional Networks.” arXiv, Jan. 28, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. C. Reyes-Aldasoro, “The proportion of cancer-related entries in PubMed has increased considerably; is cancer truly ‘The Emperor of All Maladies’?,” PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 3, p. e0173671, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Sung et al., “Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries,” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 209–249, 2021. [CrossRef]

| Definition | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Model organism | Animal model. Mouse model. Mice model. Rat model. Zebrafish model. Xenograft model. In vivo model |

| In vitro model | In vitro model. Tumor on a chip. Microfluidic model. 3D Bioprinting. 3D model. Organoid model. Spheroid model. Organ on a chip. |

| Mathematical model | Mechanistic Model. Scoring model. Prediction model. Risk model. Integrative model. Mathematical model. Prognostic model. |

| Computational model | In silico model. Computational model. Deep Learning model. Machine Learning model. Convolutional Neural Network. Agent-based model |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).