Submitted:

29 June 2023

Posted:

29 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Problems associated with current models

3. Results

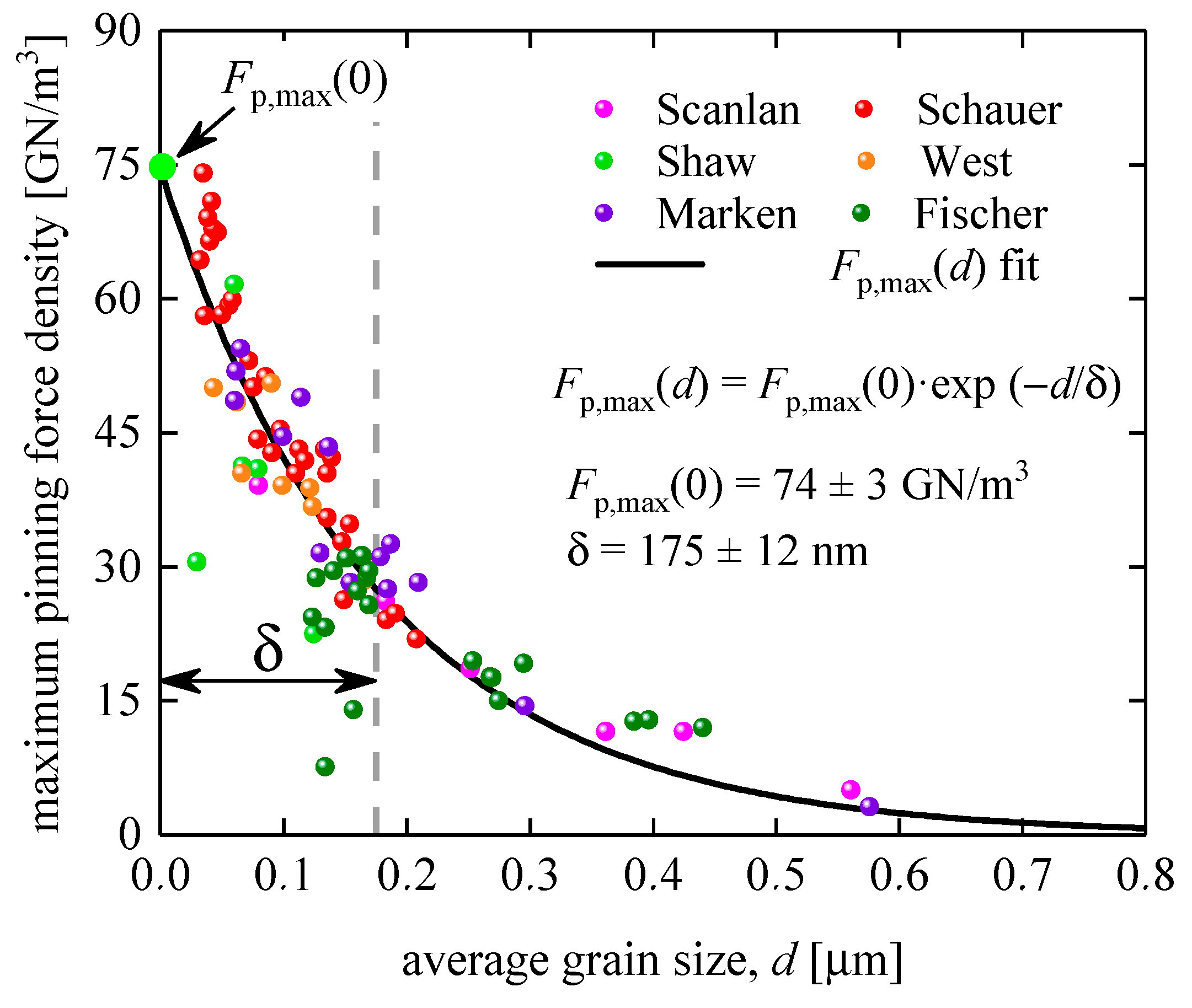

3.1. Bronze technology samples

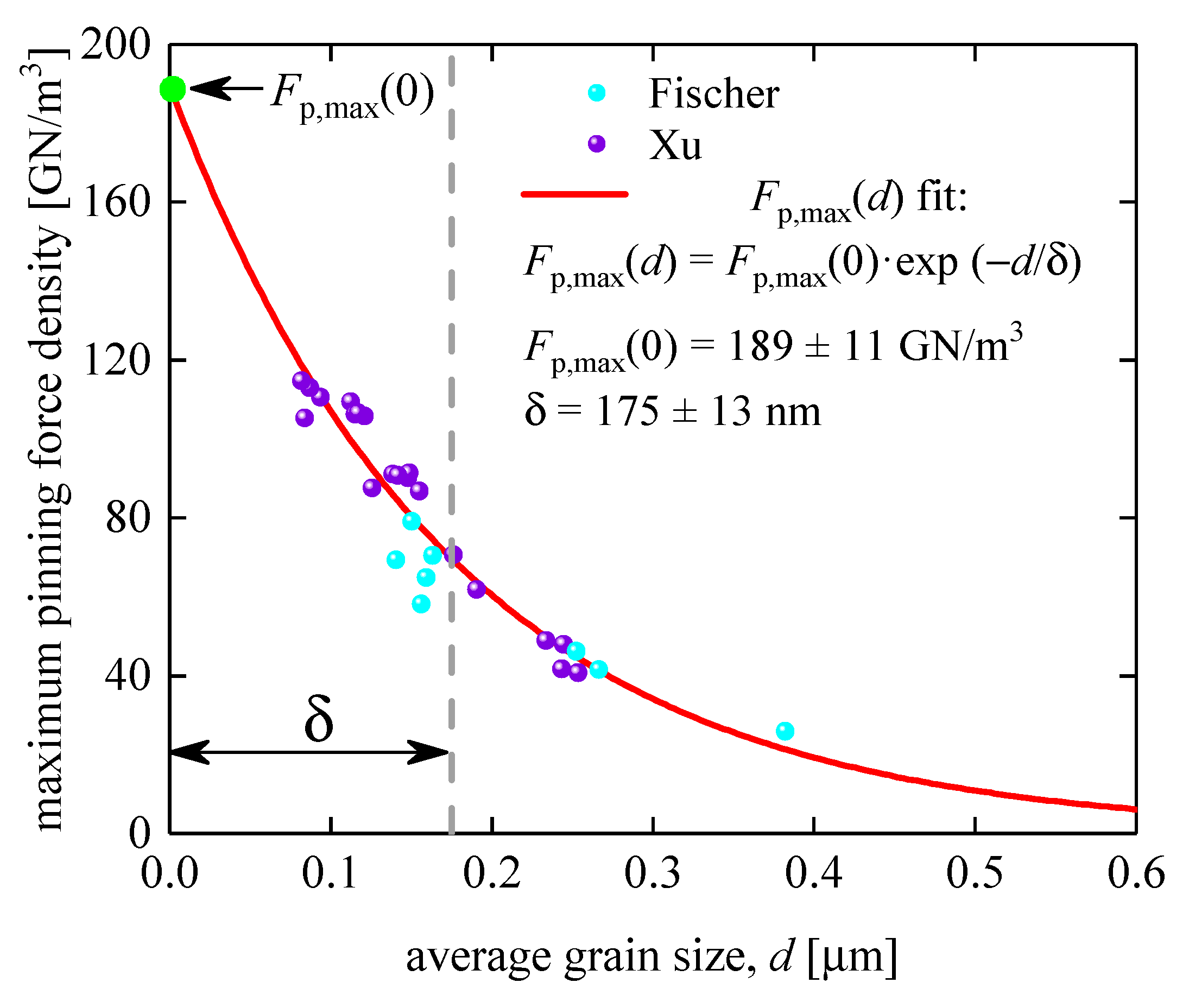

3.2. Powder-in-tube technology samples

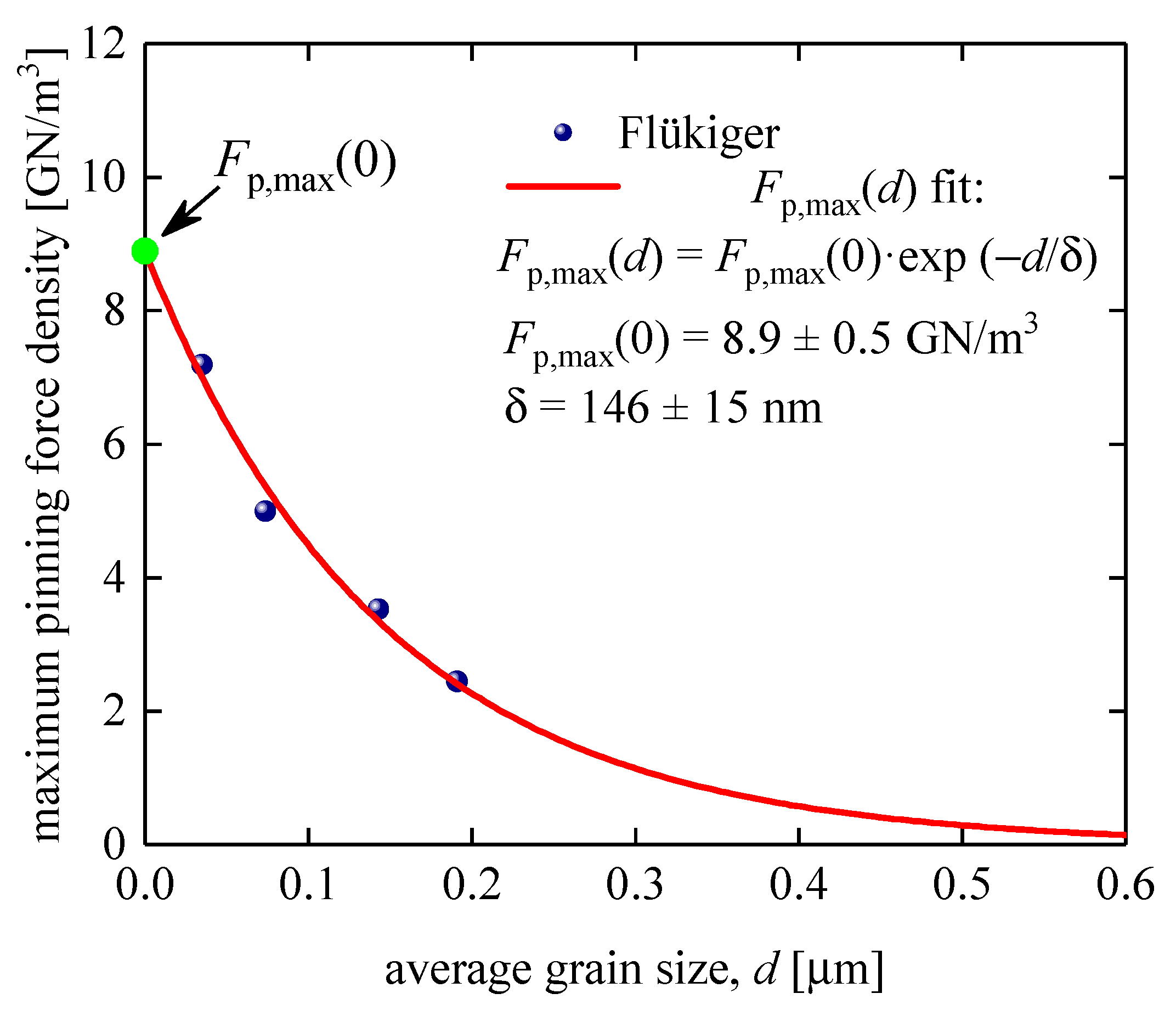

3.3. Samples fabricated by Flükiger et al by bronze technology [38]

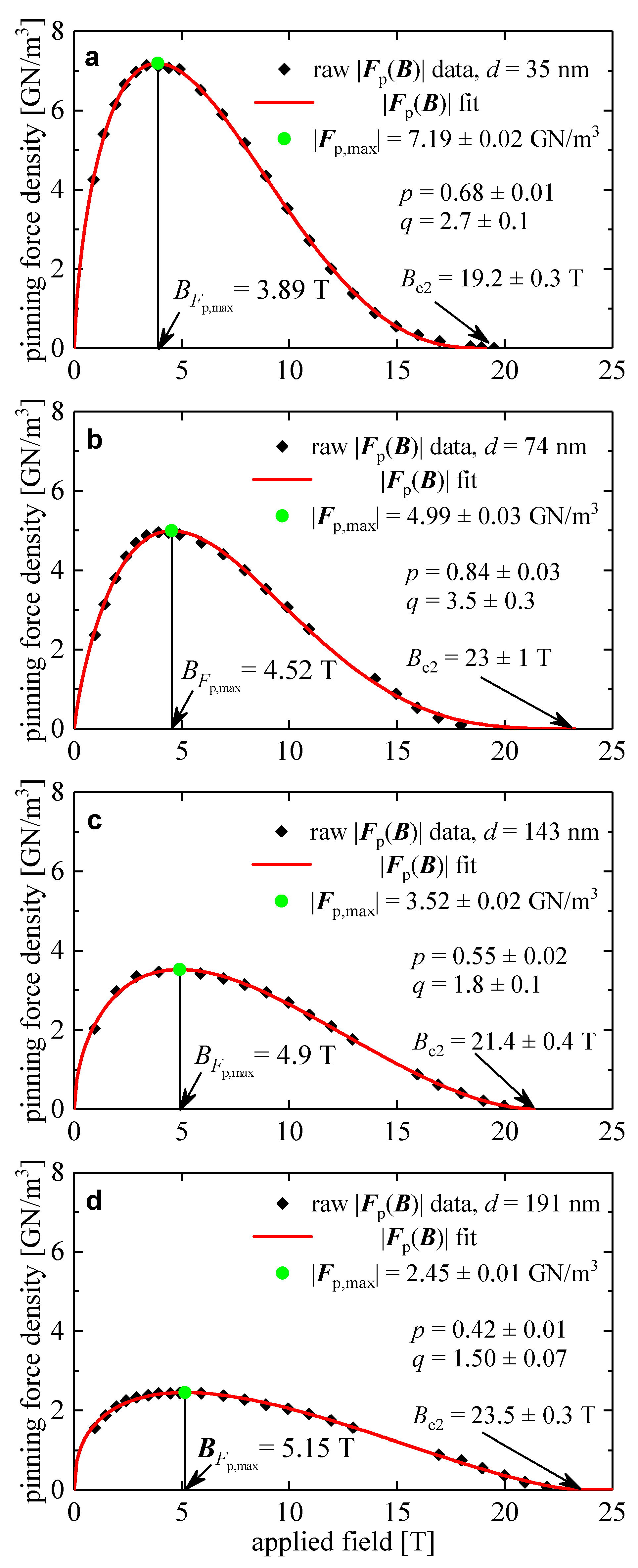

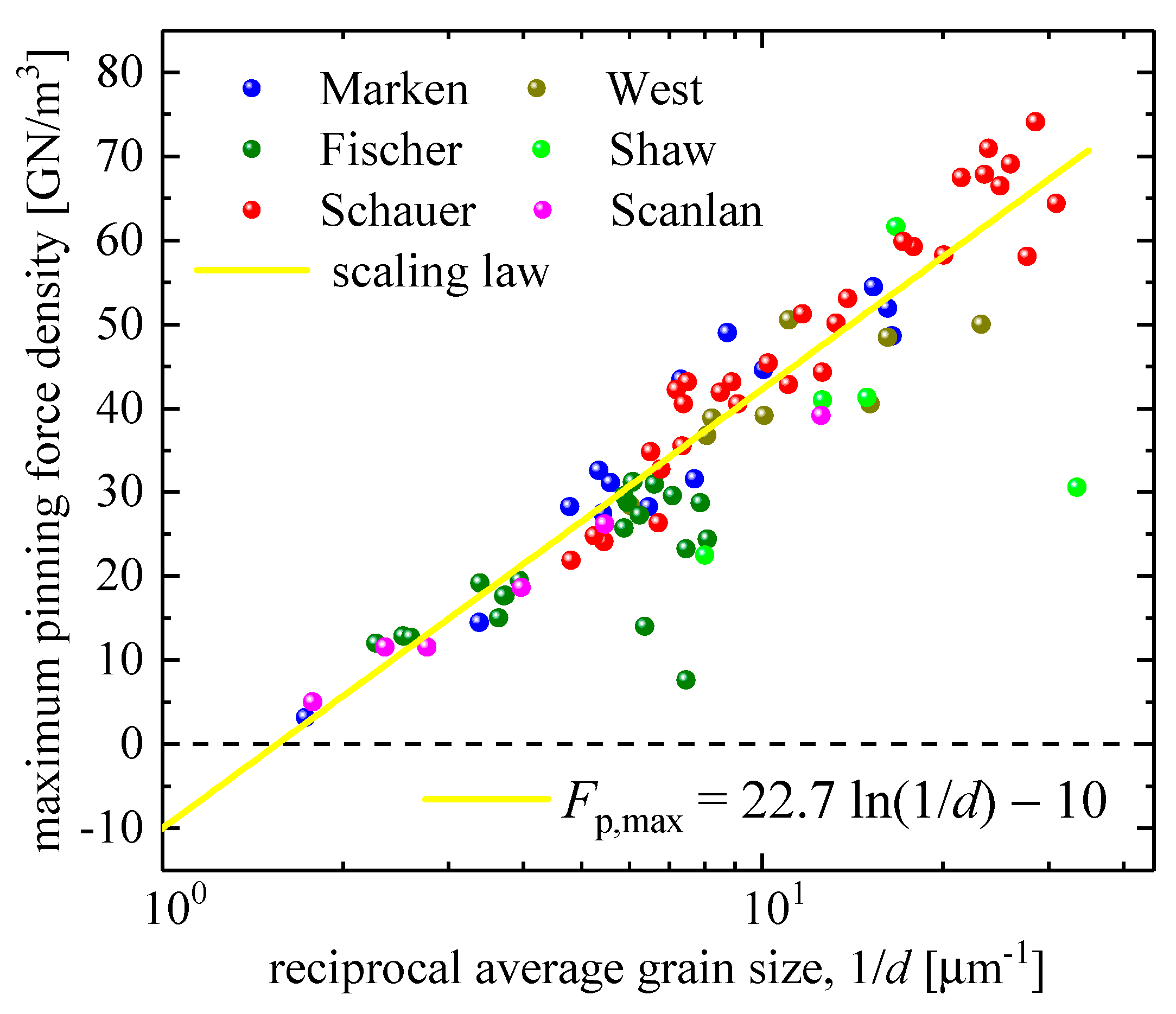

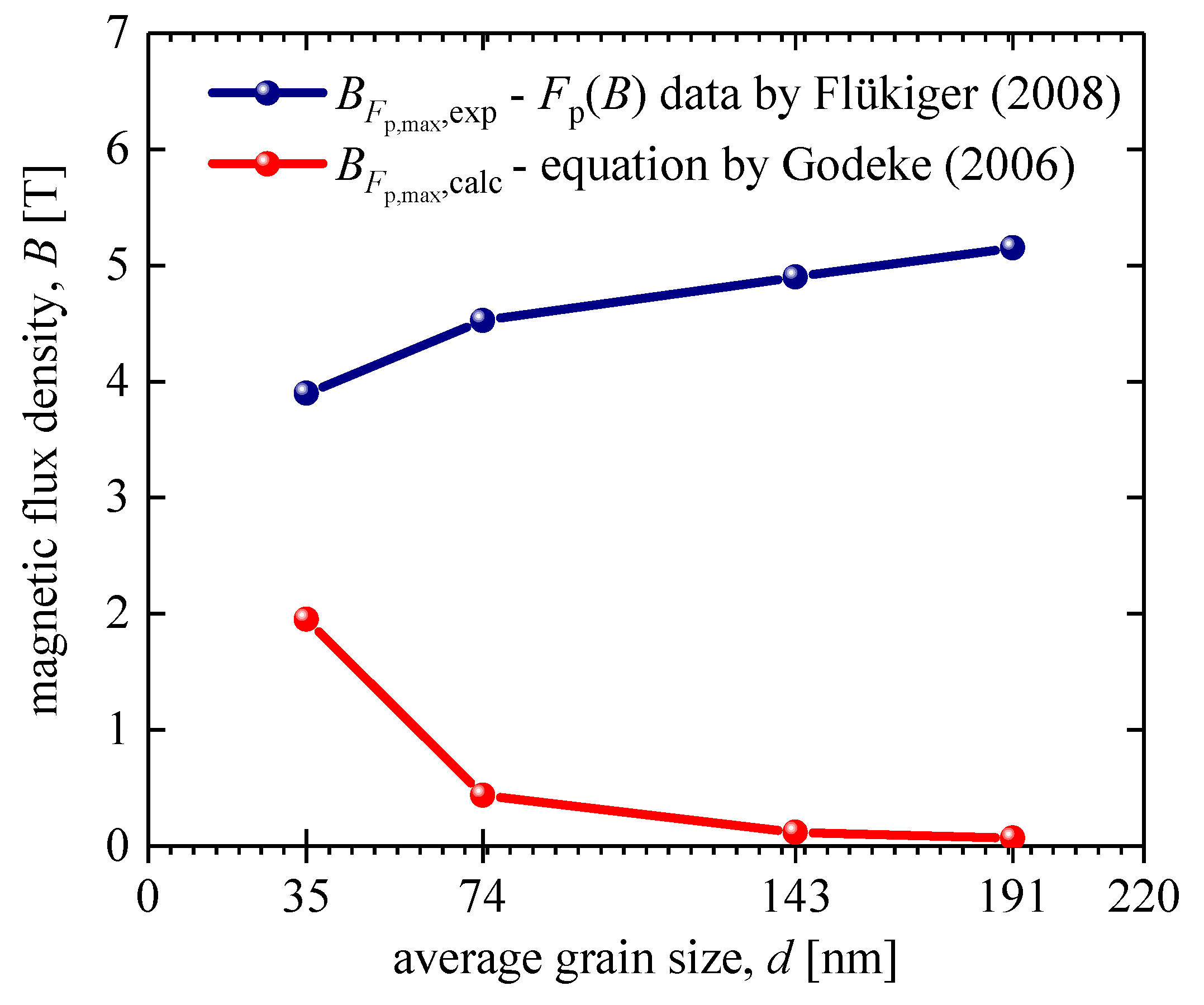

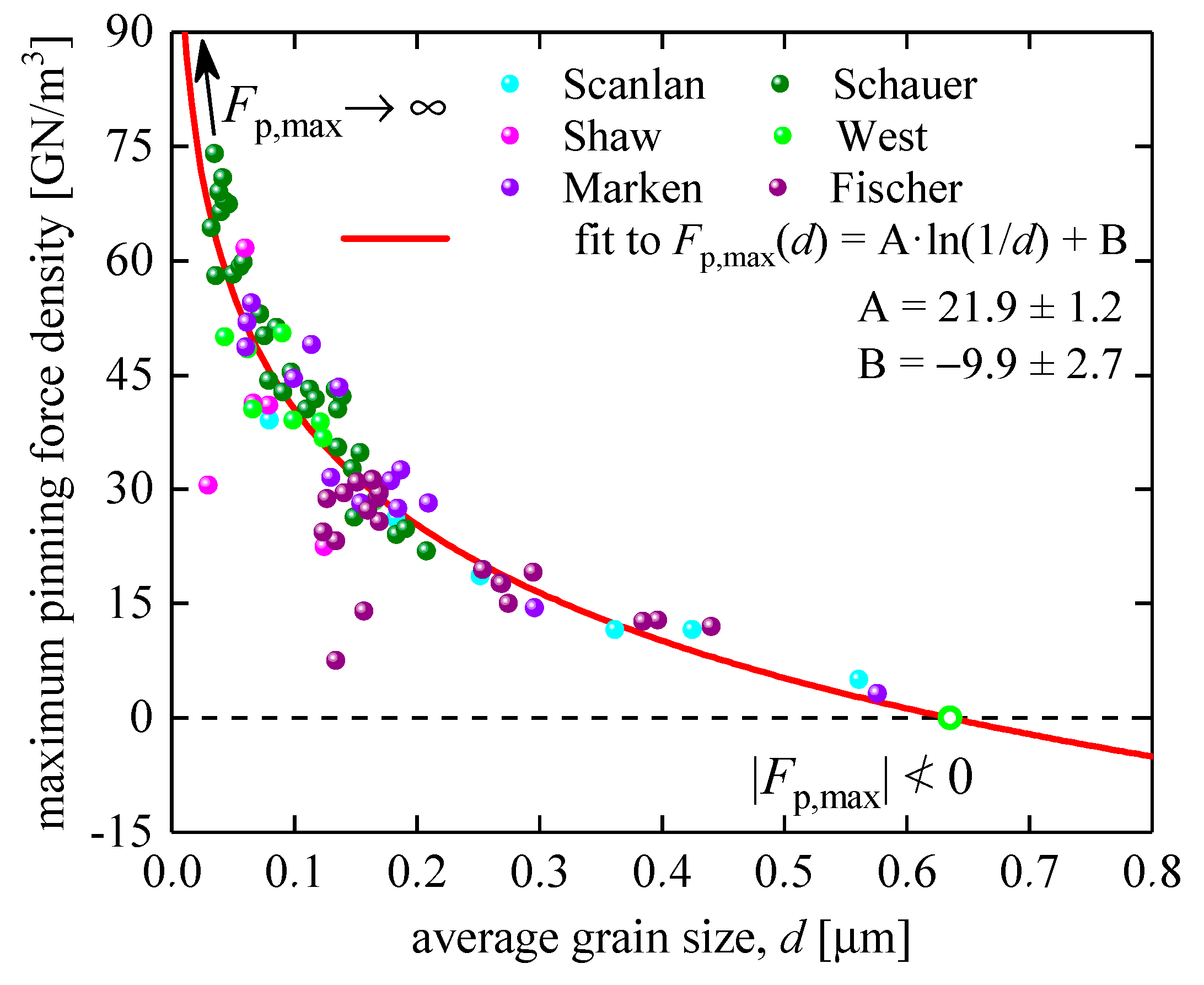

4. Discussion

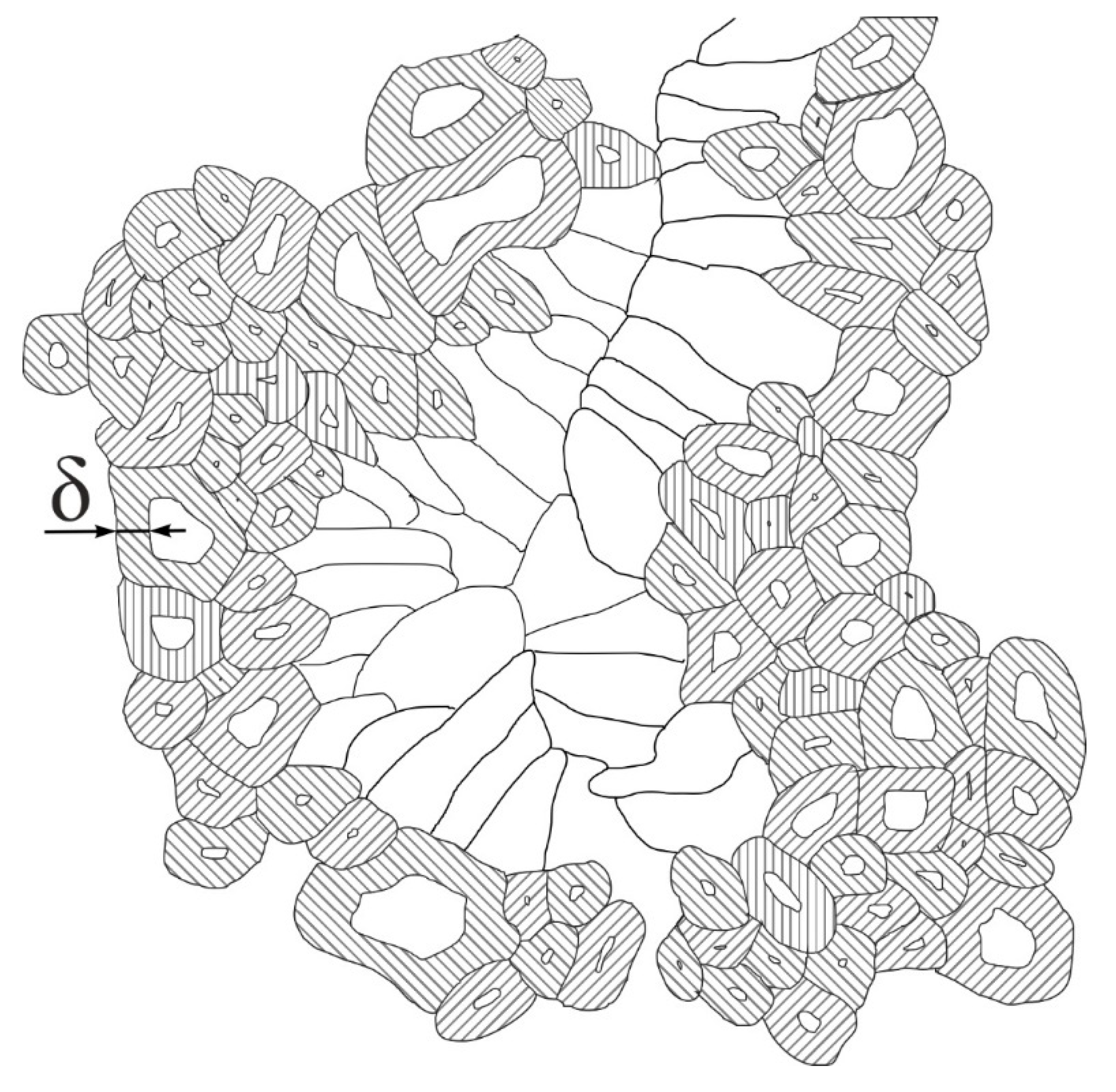

4.1. Exponential dependence of the vs grain size at

4.2. Exponential dependence of the vs grain size at

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rossi, L.; Bottura, L. Superconducting Magnets for Particle Accelerators. Rev. Accel. Sci. Technol. 2012, 05, 51–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronza, V.I.; Lelekhov, S.A.; Stepanov, B.; Bruzzone, P.; Kaverin, D.S.; Shutov, K.A.; Vysotsky, V.S. Test Results of RF ITER TF Conductors in the SULTAN Test Facility. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2014, 24, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosio, G. Nb3Sn High Field Magnets for the High Luminosity LHC Upgrade Project. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2015, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracin, P.; Ambrosio, G.; Anerella, M.; Borgnolutti, F.; Bossert, R.; Cheng, D.; Dietderich, D.R.; Felice, H.; Ghosh, A.; Godeke, A.; et al. Magnet Design of the 150 Mm Aperture Low-β Quadrupoles for the High Luminosity LHC. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2014, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karppinen, M.; Andreev, N.; Apollinari, G.; Auchmann, B.; Barzi, E.; Bossert, R.; Kashikhin, V. V.; Nobrega, A.; Novitski, I.; Rossi, L.; et al. Design of 11 T Twin-Aperture Nb3Sn Dipole Demonstrator Magnet for LHC Upgrades. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2012, 22, 4901504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrell, J.A.; Zhang, Y.; Field, M.B.; Meinesz, M.; Huang, Y.; Miao, H.; Hong, S.; Cheggour, N.; Goodrich, L. Internal Tin Nb3Sn Conductors Engineered for Fusion and Particle Accelerator Applications. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2009, 19, 2573–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballarino, A.; Bottura, L. Targets for R&D on Nb3Sn Conductor for High Energy Physics. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2015, 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelekhov, S.A.; Krasil’nikov, A. V.; Kuteev, B. V.; Kovalev, I.A.; Ivanov, D.P.; Ryazanov, A.I.; Surin, M.I.; Shavkin, S. V.; Vysotsky, V.S.; Potanina, L. V.; et al. Further Developments of Fusion-Enabling System in Russia: Suggestions on Superconductors and Current Leads for DEMO-FNS Reactor. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2018, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.J.; Larbalestier, D.C. Microstructural Factors Important for the Development of High Critical Current Density Nb3Sn Strand. Cryogenics 2008, 48, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanabria, C.; Field, M.; Lee, P.J.; Miao, H.; Parrell, J.; Larbalestier, D.C. Controlling Cu–Sn Mixing so as to Enable Higher Critical Current Densities in RRP® Nb3Sn Wires. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2018, 31, 064001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, C.; Tarantini, C.; Sung, Z.H.; Lee, P.J.; Sailer, B.; Thoener, M.; Schlenga, K.; Ballarino, A.; Bottura, L.; Bordini, B.; et al. Evaluation of Critical Current Density and Residual Resistance Ratio Limits in Powder in Tube Nb3Sn Conductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2016, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pong, I.; Hopkins, S.C.; Fu, X.; Glowacki, B.A.; Elliott, J.A.; Baldini, A. Microstructure Development in Nb3Sn(Ti) Internal Tin Superconducting Wire. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 3522–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sumption, M.; Wan, F.; Peng, X.; Rochester, J.; Choi, E.S. Significant Reduction in the Low-Field Magnetization of Nb3Sn Superconducting Strands Using the Internal Oxidation APC Approach. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2023, 36, 085008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Peng, X.; Wan, F.; Rochester, J.; Bradford, G.; Jaroszynski, J.; Sumption, M. APC Nb3Sn Superconductors Based on Internal Oxidation of Nb–Ta–Hf Alloys. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2023, 36, 035012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, S.; Baumgartner, T.; Löffler, S.; Stöger-Pollach, M.; Hopkins, S.C.; Ballarino, A.; Eisterer, M.; Bernardi, J. Analysis of Inhomogeneities in Nb3Sn Wires by Combined SEM and SHPM and Their Impact on Jc and Tc. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2023, 36, 045008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatore, C.; Bagni, T.; Ferradas-Troitino, J.; Bordini, B.; Ballarino, A. Degradation of Ic Due to Residual Stress in High-Performance Nb3Sn Wires Submitted to Compressive Transverse Force. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2023, 36, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, J.; Ortino, M.; Xu, X.; Peng, X.; Sumption, M. The Roles of Grain Boundary Refinement and Nano-Precipitates in Flux Pinning of APC Nb3Sn. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2021, 31, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryagina, I.; Popova, E.; Patrakov, E.; Valova-Zaharevskaya, E. Structure of Superconducting Layers in Bronze-Processed and Internal-Tin Nb3Sn-Based Wires of Various Designs. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 121, 233901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryagina, I.L.; Popova, E.N.; Patrakov, E.I.; Valova-Zaharevskaya, E.G. Effect of Nb3Sn Layer Structure and Morphology on Critical Current Density of Multifilamentary Superconductors. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 440, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, E.N.; Deryagina, I.L. Optimization of the Microstructure of Nb3Sn Layers in Superconducting Composites. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2018, 119, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryagina, I.; Popova, E.; Patrakov, E. Effect of Diameter of Nb3Sn-Based Internal-Tin Wires on the Structure of Superconducting Layers. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2022, 32, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottura, L.; Godeke, A. Superconducting Materials and Conductors: Fabrication and Limiting Parameters. Rev. Accel. Sci. Technol. 2012, 05, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uglietti, D.; Abacherli, V.; Cantoni, M.; Flukiger, R. Grain Growth, Morphology, and Composition Profiles in Industrial Nb3Sn Wires. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2007, 17, 2615–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banno, N. Low-Temperature Superconductors: Nb3Sn, Nb3Al, and NbTi. Superconductivity 2023, 6, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abächerli, V.; Uglietti, D.; Seeber, B.; Flükiger, R. (Nb,Ta,Ti)3Sn Multifilamentary Wires Using Osprey Bronze with High Tin Content and NbTa/NbTi Composite Filaments. Phys. C Supercond. 2002, 372–376, 1325–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abächerli, V.; Uglietti, D.; Lezza, P.; Seeber, B.; Flükiger, R.; Cantoni, M.; Buffat, P.A. The Influence of Ti Doping Methods on the High Field Performance of (Nb, Ta, Ti)3Sn Multifilamentary Wires Using Osprey Bronze. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2005, 15, 3482–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godeke, A.; Haken, B. ten; Kate, H.H.J. ten; Larbalestier, D.C. A General Scaling Relation for the Critical Current Density in Nb3Sn. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2006, 19, R100–R116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.J.; Squitieri, A.A.; Larbalestier, D.C. Nb3Sn: Macrostructure, Microstructure, and Property Comparisons for Bronze and Internal Sn Process Strands. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2000, 10, 979–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pong, I.; Oberli, L.-R.; Bottura, L. Cu Diffusion in Nb3Sn Internal Tin Superconductors during Heat Treatment. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2013, 26, 105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godeke, A. Advances in Nb3Sn Performance. In Proceedings of the Workshop Accelerator Magnet Superconductors, Design and Optimization; CERN: Geneva, Switzerland, 19–23 May 2008; pp. 24–27.

- Barzi, E.; Bossert, R.; Caspi, S.; Dietderich, D.R.; Ferracin, P.; Ghosh, A.; Turrioni, D. RRP Nb3Sn Strand Studies for LARP. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2007, 17, 2607–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godeke, A.; den Ouden, A.; Nijhuis, A.; ten Kate, H.H.J. State of the Art Powder-in-Tube Niobium–Tin Superconductors. Cryogenics 2008, 48, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, C.D.; Lee, P.J.; Larbalestier, D.C. Measurements of the Microstructural, Microchemical and Transition Temperature Gradients of A15 Layers in a High-Performance Nb3Sn Powder-in-Tube Superconducting Strand. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2006, 19, S27–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantoni, M.; Scheuerlein, C.; Pfirter, P.-Y.; Borman, F. de; Rossen, J.; Arnau, G.; Oberli, L.; Lee, P. Sn Concentration Gradients in Powder-in-Tube Superconductors. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2010, 234, 022005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, E.J. Scaling Laws for Flux Pinning in Hard Superconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 1973, 44, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew-Hughes, D. Flux Pinning Mechanisms in Type II Superconductors. Philos. Mag. 1974, 30, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekin, J.W. Experimental Techniques for Low-Temperature Measurements; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Flükiger, R.; Senatore, C.; Cesaretti, M.; Buta, F.; Uglietti, D.; Seeber, B. Optimization of Nb3Sn and MgB2 Wires. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2008, 21, 054015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, L.E.; Baumgartner, T.; Eisterer, M.; Speller, S.C.; Moody, M.P.; Grovenor, C.R.M. Understanding the Nanoscale Chemistry of As-Received and Fast Neutron Irradiated Nb3Sn RRP® Wires Using Atom Probe Tomography. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2023, 36, 085006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.M. Investigation of the Relationships between Superconducting Properties and Nb3Sn Reaction Conditions in Powder-in-Tube Nb3Sn Conductors, Master Thesis, University of Winsconsin-Madison, 2002.

- Godeke, A. A Review of the Properties of Nb3Sn and Their Variation with A15 Composition, Morphology and Strain State. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2006, 19, R68–R80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marken, K.R. Characterization Studies of Bronze-Process Filamentary Nb3Sn Composites, PhD Thesis, Wisconsin Univ., Madison, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- West, A.W.; Rawlings, R.D. A Transmission Electron Microscopy Investigation of Filamentary Superconducting Composites. J. Mater. Sci. 1977, 12, 1862–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, B.J. Grain Size and Film Thickness of Nb3Sn Formed by Solid-State Diffusion in the Range 650–800 °C. J. Appl. Phys. 1976, 47, 2143–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauer, W.; Schelb, W. Improvement of Nb3Sn High Field Critical Current by a Two-Stage Reaction. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1981, 17, 374–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, R.M.; Fietz, W.A.; Koch, E.F. Flux Pinning Centers in Superconducting Nb3Sn. J. Appl. Phys. 1975, 46, 2244–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkham, M. Introduction to Superconductivity, 2nd ed.; Dover Publications: Mineola, New York, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L.N.; Schrieffer, J.R. Theory of Superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 1957, 108, 1175–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittel, C. Introduction to Solid State Physics, 8th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, E.H. The Vortex Lattice in Type-II Superconductors: Ideal or Distorted, in Bulk and Films. Phys. Status Solidi B 2011, 248, 2305–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talantsev, E.F. The Electron–Phonon Coupling Constant and the Debye Temperature in Polyhydrides of Thorium, Hexadeuteride of Yttrium, and Metallic Hydrogen Phase III. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 130, 195901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talantsev, E.F.; Tallon, J.L. Universal Self-Field Critical Current for Thin-Film Superconductors. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paturi, P.; Huhtinen, H. Roles of Electron Mean Free Path and Flux Pinning in Optimizing the Critical Current in YBCO Superconductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2022, 35, 065007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, C.P.; Farach, H.; Creswick, R.; Prozorov, R. Superconductivity, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Godeke, A. Performance Boundaries in Nb3Sn Superconductors, PhD Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Sumption, M.D.; Peng, X. Internally Oxidized Nb3Sn Strands with Fine Grain Size and High Critical Current Density. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 1346–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talantsev, E.F. New Scaling Laws for Pinning Force Density in Superconductors. Condensed Matter 2022, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantini, C.; Kametani, F.; Balachandran, S.; Heald, S. M.; Wheatley, L.; Grovenor, C. R. M.; Moody, M. P.; Su, Y.-F.; Lee, P.J.; Larbalestier, D. C. Origin of the enhanced Nb3Sn performance by combined Hf and Ta doping. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 17845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).