1. Introduction

The 2017 Atlantic hurricane season (June – November 2017) was remembered for being especially, if not exceptionally, active, with 17 named storms, 10 hurricanes, and 6 major hurricanes sweeping across the Atlantic basin.

On 27 August 2017, a tropical storm formed in the Atlantic Ocean, just west of the Cape Verde islands, off the western coast of Africa. It rapidly intensified on its way west as it moved over warmer waters and a moister atmosphere. Within a space of 6 days, it became the strongest hurricane ever observed in the open Atlantic and it maintained its status of a category 5 hurricane for a period of 3 days [

1].

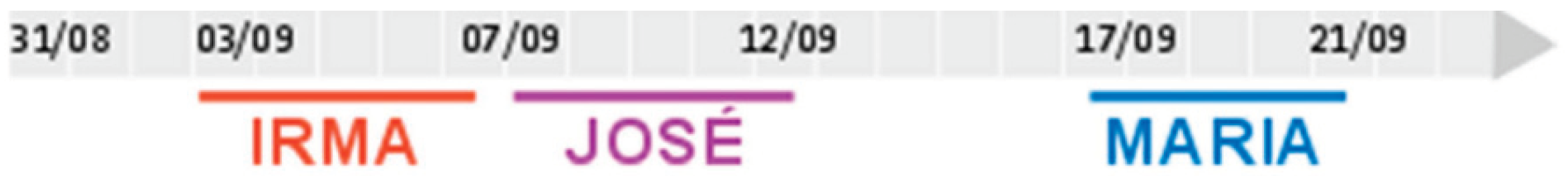

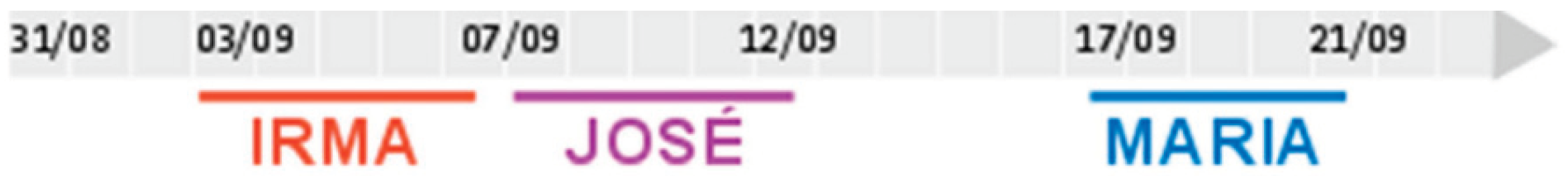

Three back-to-back hurricanes, Irma-José-Maria, all followed closely, storms which rapidly progressed to hurricane strength. September 2017 marked the first recorded instance of 2 category 5 hurricanes (Irma, Maria) making landfall in the same month.

Figure 1.

September 2017 major hurricanes islands in the

Figure 2. It was dubbed ‘Irmageddon‘[

3], by the press, referred to as a ‘nuclear hurricane’ by one government official [

4], and even qualified as the ‘hurricane of the century’ [

5]. It was considered the most powerful hurricane on record in the open Atlantic and one of the strongest landfalls ever recorded since the 1935 Labour Day hurricane. With winds of over 285km/hr [

6], it displaced hundreds of thousands of people, killing some and causing widespread destruction. Daniel Gibbs, the president of the local authority of St Martin, spoke of the destruction of 95% of the island [

7]. Irma destroyed airports, blocked ports, slowed commerce, shut down the island's essential tourism for months, which is the dominant source of revenue for the island, interrupted critical infrastructures for several weeks (transport, electricity, telecommunications, sanitation, schools, hospitals), left many homeless, and caused coastal flooding. It left undeniable physical, emotional, and psychological marks on local communities and onlookers worldwide [

8].

Figure 1.

September 2017 major hurricanes islands in the

Figure 2. It was dubbed ‘Irmageddon‘[

3], by the press, referred to as a ‘nuclear hurricane’ by one government official [

4], and even qualified as the ‘hurricane of the century’ [

5]. It was considered the most powerful hurricane on record in the open Atlantic and one of the strongest landfalls ever recorded since the 1935 Labour Day hurricane. With winds of over 285km/hr [

6], it displaced hundreds of thousands of people, killing some and causing widespread destruction. Daniel Gibbs, the president of the local authority of St Martin, spoke of the destruction of 95% of the island [

7]. Irma destroyed airports, blocked ports, slowed commerce, shut down the island's essential tourism for months, which is the dominant source of revenue for the island, interrupted critical infrastructures for several weeks (transport, electricity, telecommunications, sanitation, schools, hospitals), left many homeless, and caused coastal flooding. It left undeniable physical, emotional, and psychological marks on local communities and onlookers worldwide [

8].

The islands of Saint Martin and Saint Barthélémy (St Barth or St Bart) were the hardest hit. This natural disaster made such a substantial impact on public opinion due both to the intensity of the meteorological phenomena and to the emergency management response by the French authorities that a joint research call by the

Agence Nationale de Recherche (ANR) and the

ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur de la recherche et de l’innovation (MESRI) was issued: ‘

Ouragans 2017: Catastrophe, Risque et Résilience’ [

9]. The objective of this call, launched on 18 December 2017, just three months after the natural catastrophe, was twofold: (1) to build on knowledge of this type of extreme natural phenomena – tropical cyclones and (2) to understand its socio-environmental impact.

Four projects were funded in this call [

10], one of which APRIL -

Optimiser l’Anticipation et la Prise de décision en situation de crises extrêmes pour maintenir la RésILience de la société [

11]. Whilst these 4 projects were complementary, the APRIL project focused on how to optimize anticipation and decision-making in a context of uncertainty, i.e., during a major crisis. To address this double objective, an APRIL consortium [

12], was formed. It was comprised of four main multi-disciplinary partners from the public, academic and private sectors. The multi-disciplinarity was evident also as regards their skills in social and human sciences, earth and environmental sciences, crisis management, educational engineering, and neurosciences.

The team aimed to practice action-based research [

13], one that would produce a response to operational challenges and results conducive to the identification of recommendations as well as empower participants who would ultimately implement changes in their emergency-response action plans and strategies.

The aim of this paper is to share some of the findings of the APRIL research project. We will identify specificities and lessons learned from two territories which were heavily impacted by hurricane IRMA, the French overseas territories of St Martin and of St Barthélémy (St Barth), in the French West Indies.

We will endeavor to show how crisis management is linked to post-disaster recovery. Based on the study of the management of a major environmental disaster, hurricane IRMA, we will consider how post-disaster recovery has impacted, positively or negatively, crisis management strategies. The perspectives of local stakeholders from the islands of St Martin and St Barth will be shared. We will see how territories exposed to the same natural phenomenon have different outcomes, and some of the possible reasons why. This study identifies possible underlying causes to address governance reorganization with a view to optimizing crisis-decision making and managing rapid socioeconomic recovery.

2. Materials and Methods

The study of the 2017 cyclone crisis in the French Antilles allowed the APRIL project to better identify and understand the impact of decisions on territories. Two major questions were considered from the outset: (1) how to anticipate and (2) how optimize decision-making in a context of uncertainty.

We will see how crisis management strategies, or the lack thereof, can affect post-disaster recovery by considering the cases of the islands of St Martin and St Barth. These two territories were exposed to the same hurricane. The crisis was however handled and experienced somewhat differently on these two islands, and this was evident in the aftermath, in the recovery time, and in some of the local experiences shared.

We will identify potential risk factors (lack of information, communication breakdown, lack of confidence in public governance, financial vulnerability) and resilience factors (social participation, trust in local authorities) and examine how these can influence sustainable post-disaster recovery outcomes.

The APRIL research project was driven by three main guiding parameters. It strove to be:

1. Inclusive and applied. This was made possible through the involvement of crisis managers from the entire ORSEC [

14] chain-of-command levels: local, departmental, zonal, and national.

2. Contextualized by the significant involvement of local actors in identifying local experiences. This rendered the research conducted significantly more impactful, particularly at the local level (a large number of people were interviewed on the islands), but also fostered better understanding and sharing of local expectations, thus facilitating the implementation of changes.

3. Experimental and action based. The consortium is not exclusively academic. Our approach was validated by a steering committee, made up of civil security and crisis management professionals, so as to ensure that the research carried out in the APRIL project responded to operational issues and translated into the implementation of concrete measures. APRIL is a research-action project and therefore positions itself within an experimental development framework.

Our research methodology was based on an intensive and exhaustive data and information collection phase. Data and information were obtained via two main sources: (1) written (2) oral.

The written sources of information were based on a wide documentary data search carried out internally and externally to the ministry of Interior’s organization. Internally, information was collected from various databases: situational briefs, working papers, inter-ministerial reports on the crisis management of the IRMA hurricane, civil protection, and crisis management policy and ORSEC chain-of-command coordination documents [

15]. External sources of written information included scientific articles and articles in print and online (newspaper articles, social media).

The oral and primary source of data collection consisted of interviews. A total of 46 semi-directive and qualitative interviews were carried out with stakeholders who managed the Irma, José, and Maria hurricanes. The interviews were firstly conducted in mainland France from February 2019 onwards and were followed by a 3-week mission (35 days) [

16] in the French Antilles (Martinique, Guadeloupe, St Martin and St Barth).

A representative group of key stakeholders was identified through the careful analysis of a variety of printed pre-existing documents and interviews. Once a primary and hierarchical network of actors had been identified, secondary actors were selected based on a re-iterative approach obtained primarily through in-person interviews and firsthand discussions with the monitoring committee and on-site. This allowed for a thorough top-down and bottom-up identification process. All those directly and indirectly involved in crisis management were thus quickly identified and contacted.

St Martin and St Barth both possess the same legal status of French Overseas Collectivity [

17]. Both territories have been autonomous as regards matters of taxation, road transports, road systems, tourism, urbanization etc. since 2007. However, the French state remains competent as regards legal and commercial acts and regulations. Furthermore, these overseas collectivities islands are under the authority of the same

prefet appointed by the French government, who is under the authority of and works closely with the

prefet of Guadeloupe. The prefecture of St Martin is located in Marigot, with a local branch in Gustavia for Saint Barth. In times of crisis, both adhere to the ORSEC crisis response procedure.

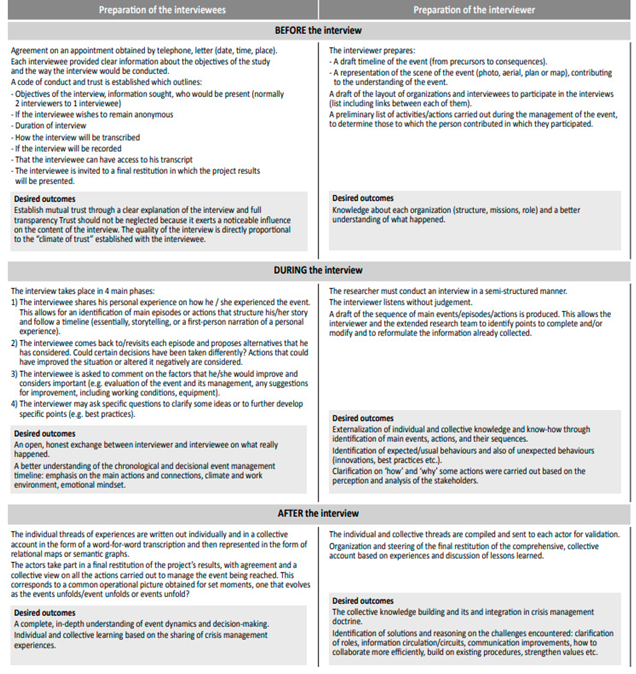

The interview process was meticulously prepared beforehand and proved essential in facilitating access to stakeholders and public authorities of the ORSEC chain of command. It also ensured the quality of the information gathered. A 3-tier approach was adopted: 1) Before the interview 2) During the interview 3) After the interview.

Table 1.

Interview data collection process.

Table 1.

Interview data collection process.

We were thus able to obtain a complete, detailed, and general panorama of the crisis dynamics based on 3 types of information:

- ➢

Event: information on the how the risk materialized.

- ➢

Actors and decisions: public and private civil protection actors involved in the hurricane Irma disaster and the individual and organizational behavior or response management were identified.

- ➢

Practical and implicit knowledge: individual perceptions and know-how were externalized or made explicit [

18].

Comprehensive information gathering, obtained from different oral sources, made it possible to achieve greater reliability of information and a more complete insight on the crisis and its management. The people interviewed were representative of their organizations, came from different hierarchical levels, environments, and cultures, and possessed varying levels of information [

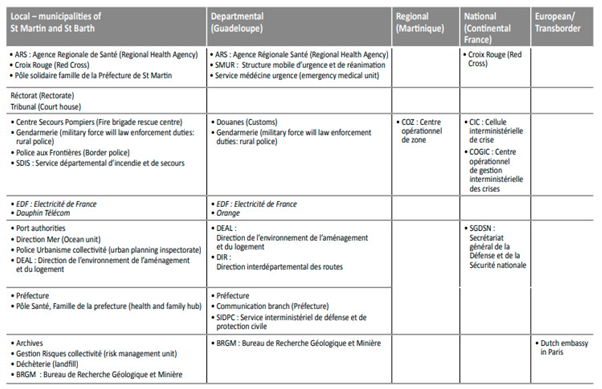

19]. The figure below shows the various organizations interviewed.

Table 2.

Actors interviewed.

Table 2.

Actors interviewed.

Our research was carried out over a period of 52 months, including a 5-week mission to Guadeloupe, Saint Martin and St Barth (between 11 March – 15 April 2019) which allowed for intensive onsite/field data collection. The mission was comprised of 3 scientists, 2 junior and 1 senior, from several fields (geography, urban planning, crisis management). Unfortunately, a second mission in April 2020 was cancelled due to the COVID-19 global pandemic outbreak. As a result, 46 interviews were carried out by the APRIL team with actors directly involved in the IRMA management effort at various administrative levels.

Our research allowed for an exhaustive and complete identification as well as formal representation/reconstruction of both the hurricane-related stages that unfolded and the associated decision-making. For the alert and response stages of the crisis management, we were able to identify: key moments in the spatial and temporal hurricane-evolution scales, stakeholder networks, type of information circulated and channels used, the actual civil security response strategies and operational actions, possible response strategies and their perceived outcomes, structural and technical adaptations, best practices, uncertainties and difficulties encountered as well as individual-level perceptions of the situation at hand.

3. Results

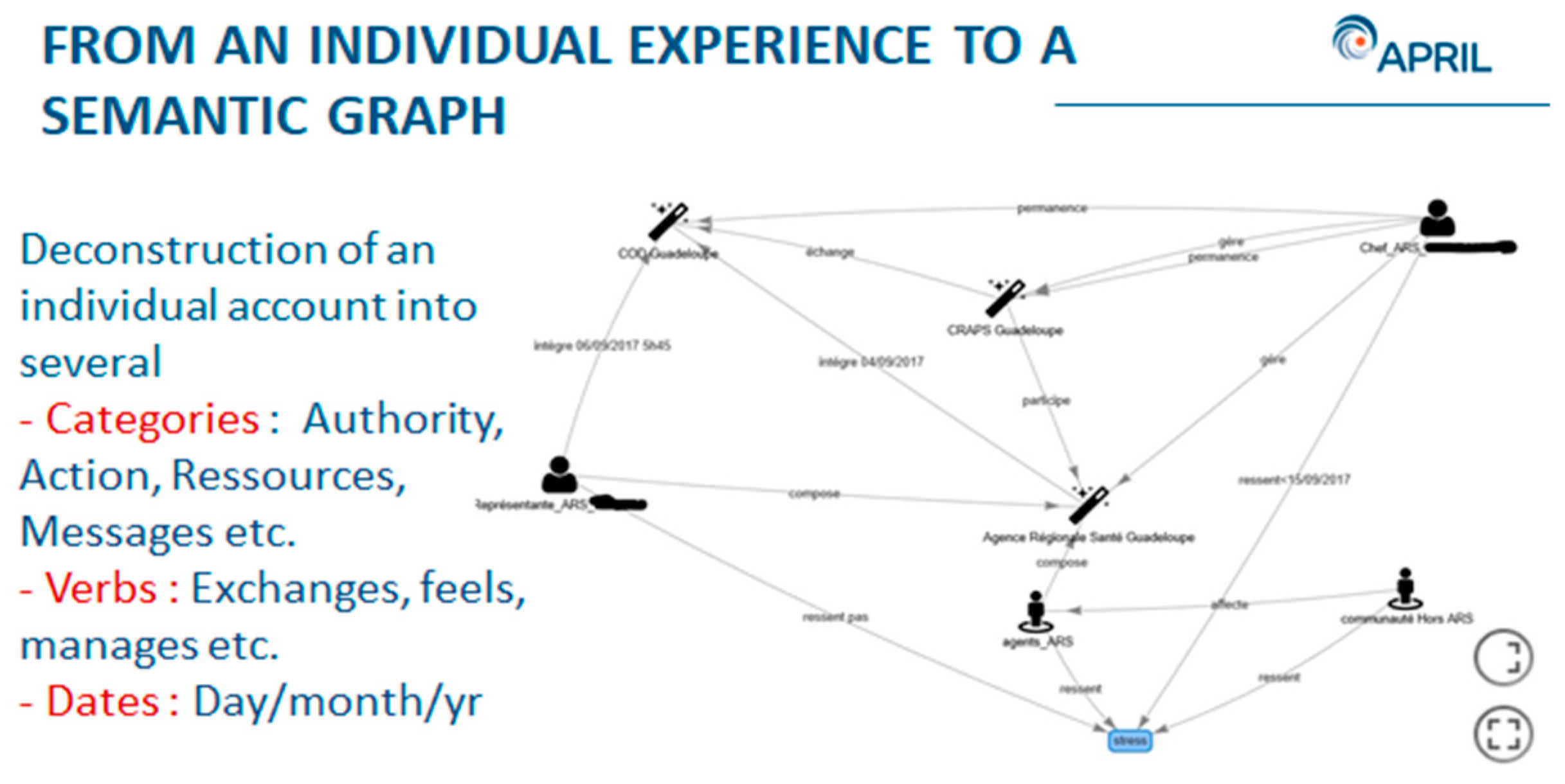

The bulk of information collected was transcribed textually and graphically using, firstly, semantic cartography or mapping. The collected data was formalized in the form of a semantic graph which structured the information into several categories and allowed for a visualization of interconnectivities.

Using individual semantic maps as a starting point, we were able to map or construct collective semantic graphs, to represent various moments in the Irma crisis management effort.

The activity of each actor within an organization allows for the identifaication of behaviors that (1) reveal the state of knowledge and, when analyzed, (2) build additional knowledge and skills [

20].

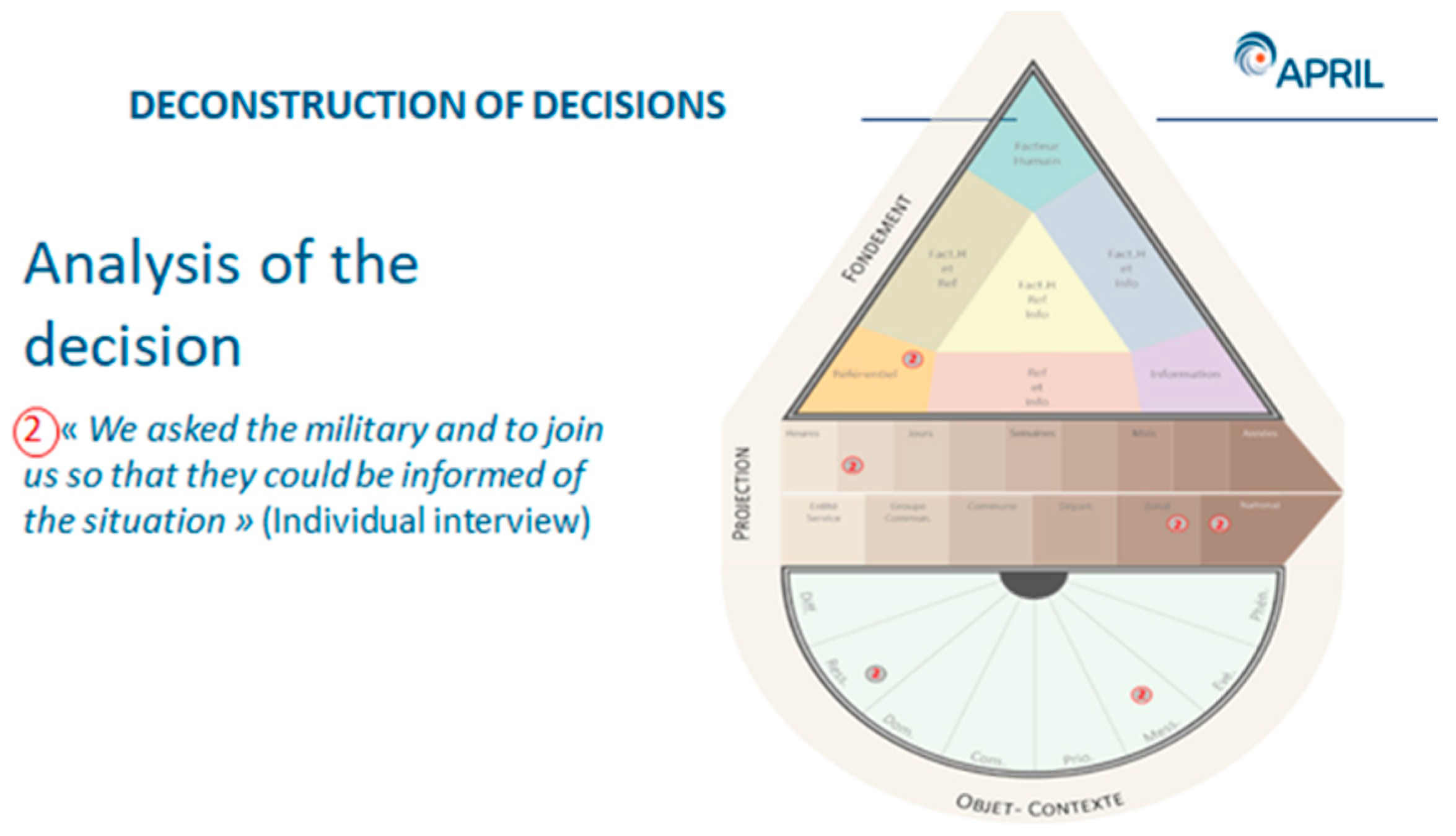

From these semantic graphs’ database, the APRIL team created a tool, available both in hard copy or electronic format, which is particularly useful during power shortages or complete blackouts, called ‘Reflexivité et analyse des décisions d’anticipation sous incertitude’, RADAR.

RADAR went one step further in that it built on the semantic maps to identify areas of uncertainty and the essential elements that govern the level of anticipation. RADAR identified four main parameters which influence the level of anticipation:

- ➢

Fundamental elements: 1) human factors (intuition, professional experience, level of stress etc.) 2) referential factors (plans, protocols etc.) 3) information available.

- ➢

Elements linked to the object and the context: anticipation can be linked to a message (press releases), resources (technical or logistics).

- ➢

Types of decisions: anticipation on the tactical, operational or strategic levels.

- ➢

Temporal projections: short, medium or long-term time scales.

Figure 3.

Deconstruction of decisions: a compass for anticipation.

Figure 3.

Deconstruction of decisions: a compass for anticipation.

RADAR would make it possible to identify and visualize areas where anticipation took place, predominantly or not, and which elements or factors were mostly present in the spatial scale (applicable to all levels of the ORSEC system) and temporal level of anticipation (short- (24-48 hours), medium- and long-term). Consequently, RADAR also makes it possible to optimize crisis management strategy coordination.

RADAR is a generic innovative tool developed by the APRIL consortium and enables the capitalization of knowledge of a crisis and compares and transfers it to another crisis situation, in order to optimally anticipate under uncertainty. This tool can be used in three different contexts, depending on the objective:

- ➢

RETEX [

21]: as a basis for a return on experience analysis, in a post-crisis setting. It permits the visualization of, for example, different types and networks of information.

- ➢

Debriefing: immediately after a real crisis or simulated crisis exercise. It would make it possible to grasp ‘how’ and ‘why’ decisions were implemented. This would allow for training on how to better anticipate.

- ➢

Crisis management: during a crisis, it would act as a compass allowing to gauge whether decision-makers are taking into account all areas in which anticipation is expected.

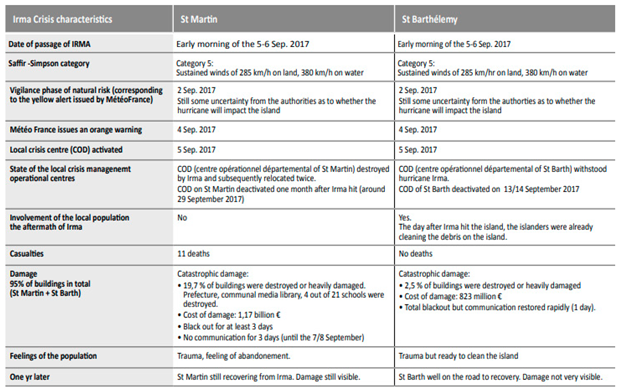

The table hereunder traces some of the significant impacts that this hurricane had on these islands.

Table 3.

Significant impacts of Irma and its management.

Table 3.

Significant impacts of Irma and its management.

Reconstruction progressed, but at different paces on the two islands. A year after Irma struck, more than 60% of badly damaged or destroyed buildings had been rebuilt by early July 2018 in Saint-Barthélémy. In Saint-Martin, where the destruction was significantly worse, the rate of reconstruction by the same period was inferior, with only 35% of buildings recovered. Two years later, the situation was still dire, with many buildings still to be rebuilt [

22]. Recovery from hurricane Irma has taken years in St Martin. Communities must be able to recover faster.

With hindsight, we may ask ourselves, why such a gap? It is possible to address this question based on the input provided by the actors interviewed within the context of this research project.

Our interviews identified broad and clear consensus regarding two main perceived challenges:

Difficulty obtaining information and communicating. The crisis was intensified by a loss of communication with the local levels (community of Saint-Martin and Saint-Barthélémy) during the first 3 days following the passage of Irma.

Lack of resources and shared coordination between ORSEC public actors to meet real, local needs and management of logistic flows. It was generally agreed that there was a need for better collaboration with local actors, such as local associations [

23], and even with the local fire-brigade, SDIS [

24], of Saint Martin. Crisis management is facilitated when there is 1) is familiarity with the territory, 2) awareness of local needs 3) fluidity of dialogue with the local population (in Creole, for example), and 4) an on-site presence. In fact, certain decisions could have been improved, better anticipated, more efficient and adapted to local needs had these four points been better understood. St Martin and St Barth both experienced the two main challenges mentioned hereinabove but St Barth crisis management addressed these issues faster and, consequently, its recovery was swifter than that of St Martin’s. In fact, the

Centre Opérationnel Départmental (COD) of St Barth was deactivated on 14 September 2017, whilst the COD of St Martin was deactivated on 29 September 2017, two weeks later.

Various factors explain the different speed and effectiveness of the interventions in St Martin and St Barth. These were specifically highlighted by the actors interviewed.

4. Discussion

Several factors were identified as having a large impact on the crisis management strategies deployed.

4.1.1. Difficult or insufficient communication

First and foremost, according to most of actors interviewed, the main reason for the delay in interventions was the difficulty or lack of communication. This was the main challenge encountered by both islands. Communication was hindered namely by:

- ➢

Technical issues: damage to the power grid, power outages and the time it took to repair the damage forced telecommunication providers to make use of fuel-based generators for many months.

- ➢

Damage to the radio antennas and aerial cables meant that the use of radio and of satellite telephones was unreliable due to the dense cloud cover from the hurricane, significantly impeding regular communication via satellite.

- ➢

Internet connection and external/off-island communications were interrupted due to major damage to submarine cables.

- ➢

Roads were damaged and rendered unpassable by debris.

- ➢

The geographical distance from the French continental territory worsened an already difficult situation. Already exposed to a degree of isolation due to their geographical remoteness from the mainland France/the metropole [

25] and to the time difference [

26], these two islands were completely cut off in terms of communication from France, other French territories in the French Antilles (Guadeloupe and Martinique) and from each other. Intra-island communication was also severely affected.

- ➢

The intensity and gravity of the hurricane was such that those who had crisis management roles elected to return home and check on their families first. They felt they had to make sure that their immediate family was safe first, to be able mentally to perform their duties. An interesting proposal was made by some of the interviewees, namely that the immediate families of crisis managers should be located in one single place, in close proximity to the crisis center. This measure would facilitate response and save precious time, a critical factor in crisis response.

- ➢

Weakened coordination between all ORSEC decision-making levels: COD – St-Martin and St Barth; COD - Guadeloupe; COZ – Martinique; COGIC and CIC-Paris. St Martin’s situation was somewhat more complex because the prefecture in St Martin was destroyed, and the local central decision-making hub rendered inoperable. The failure of telecommunication infrastructure made it very difficult for its authorities to communicate amongst themselves for a period of about 15 days. Difficulty in communication was also accentuated by different time zones. Indeed, situational briefs took place in the early hours of the morning (3am and 6am Antilles time), causing a delay in response (sending human resources, materials, etc.).

The difficulty in obtaining information and in relaying it in a timely fashion prevented the authorities of St Martin and St Barth from communicating essential information to its citizens quickly, substantially increasing the risk to public safety. It also contributed to rampant proliferation of rumors and hearsay.

In fact, the lack of communication during the first 3-4 days after Irma hit coincided with violence and an outbreak of intense pillaging and rumors [

27]. Indeed, in the immediate aftermath of hurricane Irma, St Martin was hit particularly hard by heavy looting. In light of these events, a 24-hour curfew was established and remained operational from 5 September 2017 to 6 October 2017, on St Martin (7 pm – 7 am), in order to curb disorder and prevent pillaging. Despite this measure, the island’s population felt isolated, anxious, and insecure [

28].

The local population’s trust in of the public authorities’ ability to manage the situation took a heavy blow. So much so that people left the island of St Martin to take refuge in mainland France or Guadeloupe [

29], and the media focused on various testimonials from the local population on how they felt they had been abandoned [

30].

In spite of all this, an effort was made to prepare and transmit a variety of written, verbal and visual statements containing information about the post-hurricane risks and the overall situation. Press releases, press conferences and a dedicated radio channel were used to communicate important information and updates, and, on 6 September 2017, a total of 200 gendarmes were also mobilized to keep local communities on the islands of St Martin and St Barth informed [

31].

St Barth seemed to relay information to its population in a more effective manner thanks to a dedicated communication unit which operated throughout the crisis management period, whereas the ability to maintain communication throughout the entirety of the Irma crisis was suboptimal in St Martin.

Regular communication is fundamental to maintain trust in the stewardship of public officials and in their ability to adequately manage a catastrophic crisis.

Furthermore, there is a constant need to reinforce external collaboration, that is between local, traditional media platforms or reporters (radio and print) and public officials. Reporting and news coverage could have facilitated an effective flow of communication to the local population. Reporters should be considered “friends and not foes” in such situations and can be invaluable channels to disseminate safety associated messages and essential information.

A strategy on how to effectively engage with the media, communicating during a crisis, must be prepared beforehand. What, how and when to communicate can be a very divisive topic and particularly so within a context of heavy uncertainty as management teams struggle under scrutiny. Moreover, there is an omnipresent threat of misinformation and disinformation.

Social media platforms and citizen journalism also mean that there is the risk of authorities learning about a certain issue or incident impacting their operations first on social media, instead of being duly informed through a clear and effective organizational network.

Also of note, is the risk that any ‘silence’ on the part of authorities, or “information gaps” may be filled by others. Notably, this occurred in the first few days of the Irma crisis.

Lastly, the risks of disinformation and manipulation of information are amplified in times of crisis. The need to prevent or contain this problem becomes more pressing with the passage of time.

Risk and crisis communication, therefore, require deliberate and prior, meticulous preparation. Regularly updated lists of press contacts, accurate fact sheets and background materials should be prepared beforehand. The tools, information and protocol agreed upon (who, when, and what needs to be communicated and through which channel) must be in place to be able to respond at a moment’s notice.

4.1.2. Risk culture

A second important factor was underlying risk culture. The weight and intensity of the workload of those involved in crisis management was tremendous. Irma struck the north of the Antilles arc on 5 and 6 September 2017, José passed extremely close on 9 September and Maria crossed the center of the Lesser Antilles on 18 and 19 September 2017. As a result, crisis management actors were physically exhausted. Despite the rapid succession of 3 major hurricanes, the actors carried out their missions to the best of their ability.

There was consensus among those interviewed as to the importance of memory, which helped them cope with the situation at hand. Their extensive memory of living and managing past hurricanes [

32] and their participation in a recent exercise,

Richter EU Caraibes 2017, was beneficial. In fact, RICHTER [

33] had allowed them to bolster their risk culture and better prepare for a natural catastrophe. They were able to rapidly identify which organizations to work with and were clear on each other’s roles and missions. Furthermore, working together had enabled them to update their contact lists and telephone directories and rapidly set up their crisis cells. In fact, it allowed each individual to improve, make necessary adjustments, develop skills and acquire the reflexes necessary to act quickly.

What is also of note, is that several new members of the prefecture of Guadeloupe, newly arrived in August 2017, sought at the start of their functions to familiarize themselves with the hurricane and territorial singularities and to strengthen team ties. This begs the question of whether members of emergency teams, including public officials who are dispatched to vulnerable overseas territories, should have some level of previous experience in the management of extreme phenomena and of distant territories.

4.1.3. Size of the islands

Thirdly, some point to the fact that the size of the islands might explain the differences in the speed and effectiveness of the response in the two municipalities.

Indeed, the French side of Saint Martin measures 53 km2 and according to the 2019 census, is populated by 32,489 inhabitants. St Barth, however, is smaller, with 21km2 and a total population of just less than 10 000 inhabitants, making it easier to reach the inhabitants.

4.1.4. Demographics

A fourth factor to take into consideration is demographics. Although these two islands are relatively close to each other, approximately 35- km distance apart, their socioeconomic status could not be more different.

They both rely on tourism as the primary source of income [

34]; however, their population makeup is different.

St Barth’s population combines (1) the descendants of the French settlers who populated the island from the 17

th century onwards (2), immigrants who come for the most part from Metropolitan France and other European countries, and (3) a wealthy, international, jet-setting class [

35]. St Martin’s does not include the latter and, in terms of immigration, has seen a large influx of immigrants/foreigners mostly from neighboring Caribbean countries [

36]. In fact, St Martin is a melting pot of more than 100 different nationalities [

37]. This has allowed for the English language to become one of the dominant languages on the islands. While it is difficult to quantify the exact proportion of immigrants to that of French citizens, the percentage of immigrants on the island is high, with an estimated 15,582 immigrants in 1990 (55% of the population of Saint-Martin), representing 60% of the active population.

St Martin has, since the 1960s, become an increasingly attractive territory in the Caribbean as it is considered a pathway into Europe, generating economic activity due in part to tax exemptions of the local economy and large investments in the tourism sector which benefits greatly from the island’s proximity to the Americas [

38]. The economic growth of the island has resulted in a rise in intra–Caribbean immigration to St Martin of poorer people in search of economic stability. Many of these are not massively insured and their living conditions are precarious. In fact, poverty is both a driver and a consequence of disaster and it exacerbates inequalities [

39].

The foreign population of St Barth, on the other hand, represents 13 % of the entire population, notably less than that of St Martin, and essentially originates from the European continent. Also, 21 % of the population is under 20, compared with 36 % in Saint-Martin, and 12.8 % of the population is over 60 years of age in St Barth (INSEE 2009) [

40].

St Barth’s population is wealthier, and looting did not take place on the island. The community came together immediately and worked quickly to clear the island of debris and rebuild. In fact, St Barth bounced back better and got back on its feet rapidly. Moreover, St Barth’s population proved to be more socioeconomically resilient than that of St Martin’s. In fact, poorer communities normally have less ability to cope with and recover from disaster impacts. The social, economic, linguistic, and cultural heterogeneity of the population should be taken into account by the national authorities in crisis management policies and strategies.

4.1.5. Post- traumatic psychological support

Lastly, public authorities should consider factors connected with physical vulnerability but also psychological, social and economic ones, which increase the susceptibility of an individual or a community to the impacts of these types of risks.

All those interviewed spoke of the severity of the hurricane and of the need to consider psychological trauma as a long-lasting consequence of crisis.

This trauma [

47] can be experienced by the population but of course also by first responders (firefighters, medical responders, police, civil protection). An interviewee on the island of St Martin stated that if Maria had impacted them directly like Irma, it would have been the end of them. Luckily, Maria passed just south of St Martin. Both the physical strain and emotional/mental toll on the first responders and on the inhabitants were enormous. Teams worked 24/7, day and night during the first week, after hurricane Irma impacted the islands. The islanders also found themselves in an extremely vulnerable state with damaged homes, no running or drinking water or electricity etc.

Communication flow is therefore essential as it enables the population and first responders to deal with anxiety whilst processing the situation. Of course, how an event affects an individual depends on many factors, including their characteristics, the type and characteristics of the event(s), developmental processes, the level of the trauma, and sociocultural factors, but also on the individual level of preparedness – knowledge about specific physical events and practical steps to take – can make a big difference in how the individual feels, copes and reacts.

Given the severity of the hurricane, most survivors will exhibit immediate reactions. Trauma survivors will typically resolve these reactions without severe long-term consequences. A small percentage will, however, display trauma-related stress disorders (emotional [

48] and physical disorders), which may also be triggered in a future event. This was experienced first-hand by those directly impacted by Irma, and the announcement of the imminent arrival of yet another powerful hurricane, such as Maria 10 days later, was met with much apprehension.

Children and adolescents may worry about future tropical storms. They may become overly dependent, have trouble sleeping, develop eating disorders and manifest physical symptoms (headaches, ulcers etc.)

Older adults may also require social support to reduce the effects of stress. These may stem from the fact that they are limited physically, reliant on medication, have had to be relocated, may have limited financial means and/or limited knowledge of the French language (non-fluent French speaking population).

Another category of persons at risk and which is often neglected are the first responders or front-line recovery workers. During the Irma hurricane, these individuals’ intense experiences and often prolonged separation from their families, contributed to significant mental and physical fatigue and stress.

Post-disaster psychosocial support has received increasing attention in disaster preparedness in the last two decades [

49]. In fact, a cross-national analysis of European countries found a strong association at the regional level between level of vulnerability and the inter-agency capacity to provide coordinated professional psychosocial support in response to disasters and major incidents [

50]. Many important gaps remain in our knowledge about effectiveness of psychological approaches in preventing mental health problems post-environmental crisis. Also, few studies have been carried out on children and on the investment case, or, in other words, whether the cost of implementing early interventions for large numbers of people affected, are offset by the benefits in terms of improved mental health and psychosocial wellbeing [

51].

These are some of the factors or specificities that local actors stressed and which they believe played a large part in the different management styles, or Irma experience, of the islands of St Martin and St Barth and the subsequent reconstruction timeline. These factors must be addressed to foster resilient individuals and build the foundations of strong sustainable communities.

5. Conclusion

Our research points to several factors at multiple levels that can strengthen crisis management and rapid post-disaster reconstruction.

Taking these into consideration and building on these will allow for adequate anticipatory action despite factors of vulnerability and uncertainty linked to the specificities of physical natural phenomena such as hurricanes (intensity, duration, path [

41] etc.) and a specific territory (insularity, distance, socio-cultural characteristics, impacts etc.).

In the light of the current debate on climate change, there is also growing concern that the human impact of these disasters will increase.

Climate change contributes to the increase of the ocean’s surface temperature which in turn may increase the risk of extreme weather conditions. Indeed, hotter oceans provide more energy for storms. While it remains to be seen whether the number of hurricanes will rise, scientists are certain that the intensity and severity of hurricanes will continue to increase. These trends will add to the growing costs and threats of hurricanes.

The average temperature of the world’s ocean surface has now hit an all-time high. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the global ocean heat content [

42] hit 21.1C in 2022, surpassing the previous record of 21C set in 2016 [

43].

In fact, recent research indicates that over the past 40 years, the prevalence of high-intensity cyclones has increased by around 15%. Scientists are certain that one of the consequences of climate change is an increase in the number and intensity of major hurricanes (category greater than 3) in the Pacific and Atlantic basins. There is talk of the emergence of super hurricanes all over the planet in the coming years (GIEC 2021) [

44].

Additionally, various studies warn that back-to-back hurricanes striking the same location within weeks could become common by 2100 [

45].

Low-lying coasts and small islands, such as in the French Antilles, are particularly vulnerable and will see increased vulnerability to hurricanes and ensuing a rise in induced coastal floods [

46].

The implications are obvious: the optimization of hurricane preparation and rapid response and recovery are critical.

It is imperative to anticipate, inform and prepare for natural disasters. Safeguarding people’s lives and livelihoods and limiting material damage largely depend on anticipatory capabilities and upstream preparation to ensure optimal responsiveness.

A robust disaster risk reduction strategy must anticipate and address risk drivers. Reducing exposure and vulnerability to a hazard, and developing efficient crisis preparedness, will contribute to rapid disaster recovery.

References

- Category 5 storms are among the strongest tropical cyclones that can form on earth and do not usually maintain that strength for periods longer than 1 day. Irma and Maris reached category 5 in their intensity and then weakened to category 4 and then regained strength once more attaining a category 5 status once again. Irma stayed at category 5 for 3 days and Maria for 1 day, 4 hours and 15 minutes. List of Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes - Wikipedia.

- https://www.gouvernement.fr/sites/default/files/contenu/piece-jointe/2018/09/dp_irma_-_bilan_1_an.pdf ; Gray, B., (2018). Supporting situational awareness during disasters: the case of hurricane Irma.

- https://www.miaminewtimes.com/news/irma-miamians-just-had-their-first-taste-of-hurricane-misery- 9668516; https://www.lesoir.be/112868/article/2017-09-07/irmageddon-louragan-la-une-de-la-pressefrancaise; https://www.facebook.com/Liberation/posts/10155585002297394/.

- SINT MAARTEN GOT IT WORSE! But St. Thomas Has No Electricity Only Satellite Phones Work on St. John And Footage of Hurricane Irma Over St. Croix - Virgin Islands Free Press (vifreepress.com).

- Irma was the strongest Atlantic hurricane since records were first kept, in 1851 (Hurricane Irma | The New Yorker).

- Detailed Meteorological Summary on Hurricane Irma (weather.gov).

- Irma : l'île de Saint-Martin "à 95 % détruite" (lepoint.fr).

- Hurricane Irma Skirts Puerto Rico, Leaves 1 Million Without Power (nbcnews.com) ; Death toll rises as 'apocalyptic' Irma wreaks havoc across Caribbean | Hurricane Irma | The Guardian ; C:\Users\Tony Gibbs\Documents\Now\PAHO\SintMaarten\2017\Report text and covers.wpd.

- https://anr.fr/fileadmin/documents/2017/ANR-CP-AAP-OURAGAN-18-decembre-2017.pdfhttps://anr.fr/fileadmin/documents/2017/ANR-CP-AAP-OURAGAN-18-decembre-2017.pdf.

- Colloque "OURAGANS 2017 : catastrophe, risque et résilience", les 21 et 22 novembre 2022 | ANR.

- Projet APRIL | IHEMI.

- Bureau de recherches géologiques et minières (BRGM), France's leading public institution for Earth Science applications for the management of surface and subsurface resources and risks : French geological survey | BRGM ; Institut des hautes études du ministère de l'Intérieur (IHEMI), provides training to senior public and private sector officials and conducts scientific research : Institut des hautes études du ministère de l'Intérieur - IHEMI ; Laboratoire techniques, territoires et sociétés (LATTS) of Gustave Eiffel University, specializing in the issues of the city, territories, space, production, today and in history ; École Française de l'Heuristique (EFH), a SME providing training and coaching for organisations with a view to reduce employee’s cognitive load : École Française de l'Heuristique (efh.fr).

- Lewin, K., Action research and minority problems, in G.W. Lewin (Ed.) Resolving Social Conflicts. New York: Harper & Row (1948).

- The ORSEC system is a French national emergency plan or civil security plan for all crisis response. It organizes under the authority of the maire (when one administrative commune is affected) and prefect (when various communes are impacted), the mobilization, the implementation and the coordination of the actions of any public and private authority involved in the general protection of the populations.

- French civil protection response organization is detailed in the ORSEC (organisation de la réponse de sécurité civil) plan, which identifies operational actors responsible for emergency response or intervention : emergency medical service (SAMU) ; the police ; the gendarmerie ; the interdepartmental fire and rescue service (SDIS) ; associations ; the communes ; EPCIs (intercommunity); the Departmental Council ; critical network operators ; companies.

- 11 March – 15 April 2019. The second wave of interviews programmed for a period of 21 days in April 2020 was cancelled due to the COVID 19 pandemic with the shutdown of borders and with the nonavailability of our interviewees who were swamped down with the management of this unprecedented global health crisis.

- Collectivité d’Outre – Mer (COM).

- Nonaka I., Takeuchi H., The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. Oxford University Press, p. 304, 1995.

- Middleton D., Talking work: Argument, Common Knowledge and improvisation in Multi-disciplinary Child Development Teams, chapter for Yrjo Engeström & David Middleton Cognition and Communication at Work, Cambridge University Press, p. 233-256, 1996.

- Gherardi S., The background and foundation for the practice-turn in organizational learning. Colloque ANVIE, 2006, p. 3, 2006.

- RETEX : retour d’expérience – experience feed-back, post-crisis.

- Daniel Gibbs, président de la collectivité de Saint-Martin, en garde à vue pour soupçons de favoritisme - Outre-mer la 1ère (francetvinfo.fr).

- For example to distribute water, food and goods.

- Service d’incendie et de secours (SDIS), local fire – brigade service who could have has a more substantial role in the crisis response.

- The geographical distance between France and (1) St Martin is approximately 6 674 km and (2) Saint-Barth, 6,669 km.

- St Martin and St Barth are situated in the Atlantic Standard Timezone (6 hours ahead of Paris time in the Summer and + 5 hours in the Winter).

- Irma : les trois intox qui ont été démenties après le passage de l'ouragan (francetvinfo.fr).

- Confronted with intense looting and gun shots heard in the night by many inhabitants of St Martin, many citizens barricaded themselves at home.

- According to our interview with the Police aux Frontières of St Martin more than 7000 islanders left St Martin in the days that followed Irma, to take refuge in Guadeloupe, Martinique and mainland France.

- Saint-Martin : « Les gens se sentent abandonnés » (la-croix.com).

- Ministère de l'Intérieur et des Outre-mer sur Twitter : "🔴#Cyclone #Irma🌀Dispositif de sécurisa° et d'info. de la population : 640 gendarmes en #Guadeloupe & 200 pr #SaintMartin et #SaintBarthélémy https://t.co/FuUkfccHXa" / Twitter.

- Even though many actors said that they felt quite overwhelmed with unexpected force of the Irma hurricane. However, previous hurricane experience did in a way prepare certain actors for this type of phenomena.

- Richter EU Caraibes 2017 training exercise took place between 21 - 25 March 2017 Microsoft Word - EU RICHTER CARAIBES 2017 dossier de presse (martinique.gouv.fr).

- Tourism accounts for 80% of the economy and this industry employs most of the inhabitants on the the island. The gross domestic product by sector in Saint Martin is 0.4% agriculture, 18.3% industry, and 81.3% tourism.

- https://www.iedom.fr/IMG/pdf/ne134_portrait_saint-barth_panorama_2010_version_anglaise.pdf.

- Benoit C., « Saint Martin : un nouveau droit des étrangers », Plein droit, 2007/3 (n° 74), p. 17-20. URL : https://www.cairn.info/revue-plein-droit-2007-3-page-17.htm. [CrossRef]

- Redon M., « Migrations et frontière : le cas de Saint-Martin », Études caribéennes, 8 décembre 2007. http://journals.openedition.org/etudescaribeennes/962. [CrossRef]

- Chardon J.P., Hartog T. 1995. Saint-Martin ou l’implacable logique touristique, Cahiers d’Outre-mer, n° 189, p. 21-34.

- Hallegatte, S., Vogt-Schilb, A., Rozenberg, J. et al. From Poverty to Disaster and Back: a Review of the Literature. EconDisCliCha 4, 223–247 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Évolution et structure de la population en 2009 − Recensement de la population – Résultats pour toutes les communes, départements, régions, intercommunalités... | Insee.

- The path can only be predicted 3-5 days in advance and can constantly change in function of atmospheric conditions.

- The amount of heat stored in the upper 2,000 meters of the ocean.

- 2022 was world’s 6th-warmest year on record | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (noaa.gov)).

- Summary for Policymakers (ipcc.ch).

- Xi, D., Lin, N. & Gori, A. Increasing sequential tropical cyclone hazards along the US East and Gulf coasts. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 258–265 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Biguenet, M., Chaumillon, E., Sabatier, P., Bastien, A., Geba, E., Arnaud, F., Coulombier, T., and Feuillet, N.: Hurricane Irma: an unprecedented event over the last 3700 years? Geomorphological changes and sedimentological record in Codrington Lagoon, Barbuda, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. preprint., in review, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Emotional distress, or post-traumatic stress disorder, will manifest itself with feelings that can range from shock, anxiety, depression, isolation, abandonment, trouble sleeping feeling of helplessness, increase in violence, before, during, and after major crisis events.

- Anxiety, anger, sadness, this is more so when the trauma occurs at a young age, as a child or a teen (van der Kolk BA, Roth S, Pelcovitz D, Sunday S, Spinazzola J. Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma. J Trauma Stress. 2005 Oct;18(5):389-99. PMID: 16281237). [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll S. E, Watson P, Bell C. C, Bryant R. A, Brymer M. J, Friedman M. J, et al. Five essential elements of immediate and mid-term mass trauma intervention: Empirical evidence. Psychiatry. 2007;70:283–315.

- https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.12113. [CrossRef]

- Dückers MLA, Thormar SB, Juen B, Ajdukovic D, Newlove-Eriksson L, Olff M. Measuring and modelling the quality of 40 post-disaster mental health and psychosocial support programmes. PLoS One. 2018 Feb 28;13(2):e0193285. PMID: 29489888; PMCID: PMC5830995. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).