Submitted:

29 June 2023

Posted:

30 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

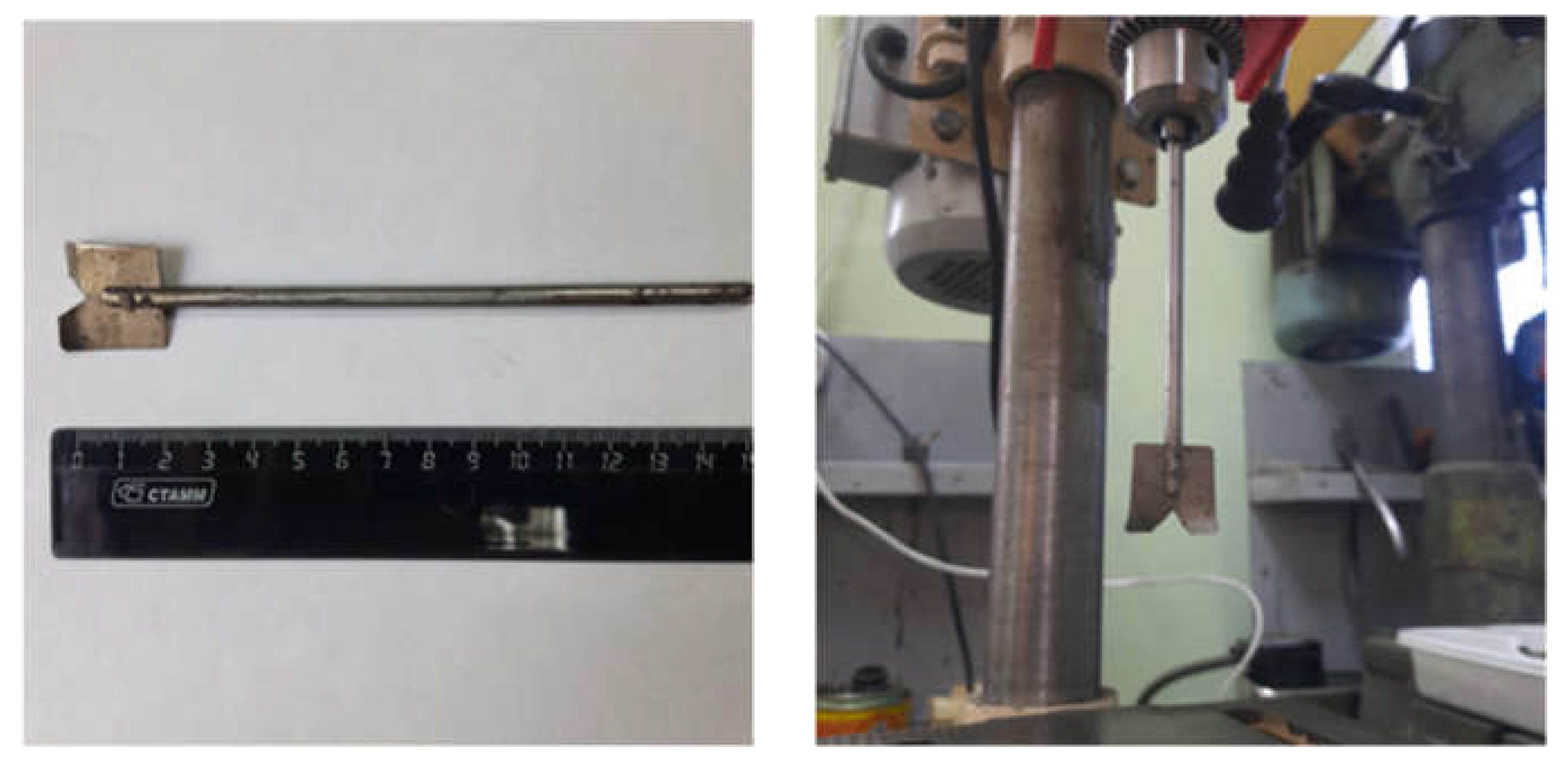

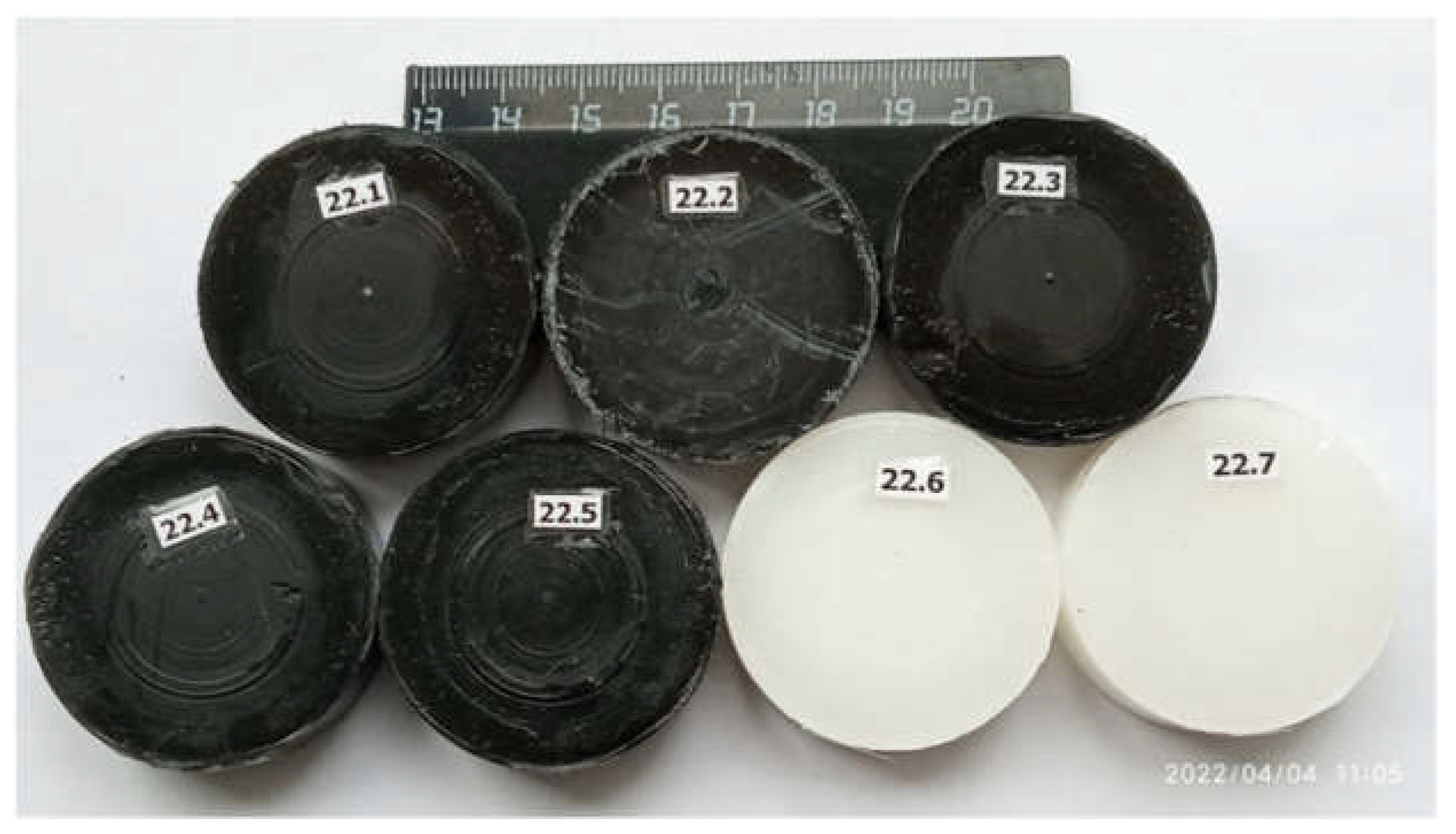

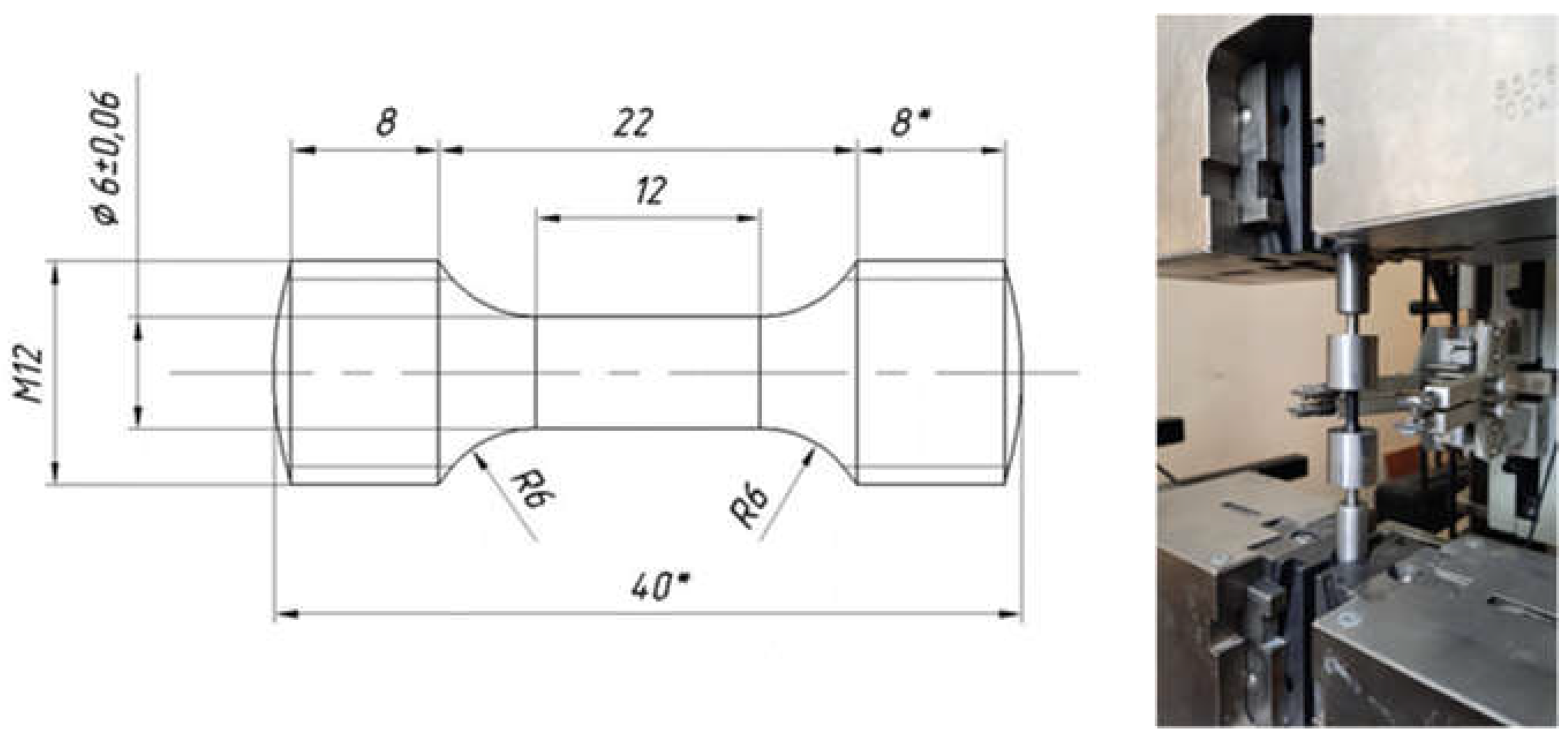

2. Materials and Methods

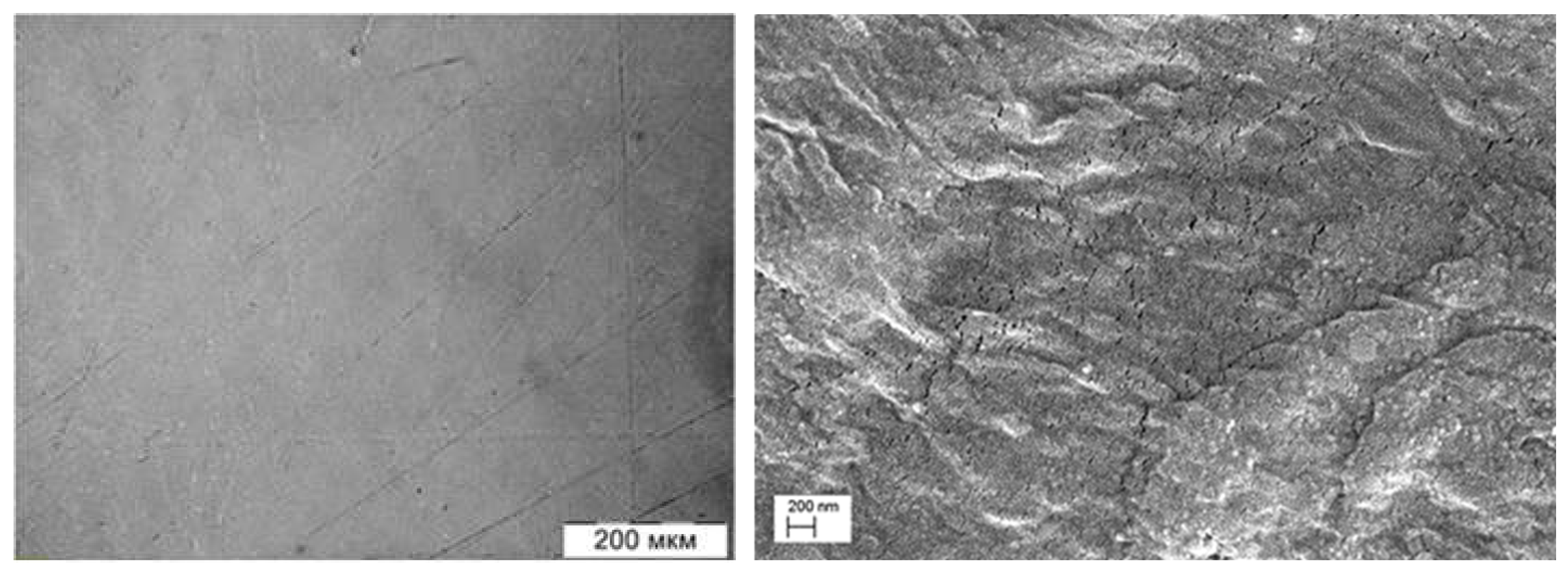

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kelly, J.M. Ultra-High Molecular Weight Polyethylene, J. Macromol. Sci., Polym. Rev. 2002, 42, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieraj, M.C.; Rimnac, C.M. Ultra high molecular weight polyethylene: Mechanics, morphology, and clinical behavior. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2009, 2, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, M.; Naqvi, R.A.; Abbas, N.; Khan, S.M.; Nawaz, S.; Hussain, A.; Zahra, N.; Khalid, M.W. Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight-Polyethylene (UHMWPE) as a Promising Polymer Material for Biomedical Applications: A Concise Review. Polymers 2020, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammarullah, M.I.; Afif, I.Y.; Maula, M.I.; Winarni, T.I.; Tauviqirrahman, M.; Jamari, J. Tresca stress evaluation of Metal-on-UHMWPE total hip arthroplasty during peak loading from normal walking activity. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 63, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentra, M.R.; Marques, M.F.V. Synthetic Polymeric Materials for Bone Replacement. J. Compos. Sci. 2020, 4, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Q.Md.Z.; Kowser, Md.A.; Chowdhurry, M.A.; Chani, M.T.S.; Alamry, K.A.; Hossain, N.; Rahman, M. Modeling Fracture Formation, Behavior and Mechanics of Polymeric Materials: A Biomedical Implant Perspective. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chricker, R.; Mustacchi, S.; Massarwa, E.; Eliasi, R.; Aboudi, J.; Haj-Ali, R. Ballistic Penetration Analysis of Soft Laminated Composites Using Sublaminate Mesoscale Modeling. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Z.; Cheng, X.; Fan, Q.; Wang, F.; Miao, C. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of the Effect of Projectile Nose Shape on the Deformation and Energy Dissipation Mechanisms of the Ultra-High Molecular Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE) Composite. Materials 2021, 14, 4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, K. Role of carbon nanotubes in the ballistic properties of boron carbide/carbon nanotube/ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene composite armor. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 4137–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtertser, A.A.; Zlobin, B.S.; Kiselev, V.V.; Shemelin, S.D.; Bukatnikov, P.A. Characteristics of Reinforced Ultra-High Molecular Weight Polyethylene during Its Ballistic Penetration. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 2020, 61, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauffres, D.; Lame, O.; Vigier, G.; Dore, F. Microstructural origin of physical and mechanical properties of ultra high molecular weight polyethylene processed by high velocity compaction. Polymer 2007, 48, 6374–6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlobin, B.S.; Shtertser, A.A.; Kiselev, V.V.; Shemelin, S.D.; Poluboyarov, V.A.; Zhdanok, A.A. Cyclic Impact Compaction of Ultra High Molecular Weight Polyethylene Powder. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 2017, 58, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlobin, B.S.; Shtertser, A.A.; Kiselev, V.V.; Shemelin, S.D. Impact Compaction of Ultra High Molecular Weight Polyethylene. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 894, 012091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtertser, A.; Zlobin, B.; Kiselev, V.; Shemelin, S.; Ukhina, A.; Dudina, D. Cyclic Impact Compaction of an Ultra High Molecular Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE) Powder and Properties of the Compacts. Materials 2022, 15(19), 6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chih, A.; Anson-Casaos, A.; Puertolas, J.A. Frictional and mechanical behaviour of graphene/UHMWPE composite coatings. Tribol. Int. 2017, 116, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yin, Z.; Li, H.; Gao, G.; Zhang, X. Friction and wear characteristics of ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) composites containing glass fibers and carbon fibers under dry and water-lubricated conditions. Wear 2017, 380–381, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panin, S.V.; Kornienko, L.A.; Alexenko, V.O.; Buslovich, D.G.; Bochkareva, S.A.; Lyukshin, B.A. Increasing Wear Resistance of UHMWPE by Loading Enforcing Carbon Fibers: Effect of Irreversible and Elastic Deformation, Friction Heating, and Filler Size. Materials 2020, 13, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Sinha, S.K. Wear performances and wear mechanism study of bulk UHMWPE composites with nacre and CNT fillers and PFPE overcoat. Wear 2013, 300, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S.L.; Gao, P.; Yang, X.G.; Yu, T.X. Toughening high performance ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene using multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Polymer 2003, 44, 5643–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, G.; Zhong, W.H.; Ren, X.; Wang, X.Q.; Yang, X.P. Structure, mechanical properties and friction behavior of UHMWPE/HDPE/carbon nanofibers. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2009, 115, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markevich, I.A.; Selyutin, G.E.; Drokin, N.A.; Selyutin, A.G. Electrical and Mechanical Properties of the High-Permittivity Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight Polyethylene-Based Composite Modified by Carbon Nanotubes. Tech. Phys. 2020, 65, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtertser, A.A.; Ulianitsky, V.Y.; Batraev, I.S.; Rybin, I.S. Production of Nanoscale Detonation Carbon using a Pulse Gas-Detonation Device. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2018, 44, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtertser, A.A.; Rybin, D.K.; Ulianitsky, V.Y.; Park, W.; Datekyu, M.; Wada, T.; Kato, H. Characterization of Nanoscale Detonation Carbon Produced in a Pulse Gas-Detonation Device. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2020, 101, 107553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlobin, B.S.; Kiselev, V.V.; Shtertser, A.A.; Shemelin, S.D. Method of producing metal-polymer sample based on UHMWPE and sample obtained using said method. RU Patent 2691789, 18 June 2019.

- Shtertser, A.A.; Ul’yanitskii, V.Yu.; Rybin, D.K.; Batraev, I.S. Detonation Decomposition of Acetylene at Atmospheric Pressure in the Presence of Small Additives of Oxygen. Combus. Explos. Shock Waves 2022, 58, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M-F.; Lourie, O.; Dyer, M.J.; Moloni, K.; Kelly, T.F.; Ruoff, R.S. Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Under Tensile Load. Science 2000, 287, 637–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poot, M.; van der Zant, H.S.J. Nanomechanical properties of few-layer graphene membranes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 063111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Powder Composition | Sample Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter, mm | Height, mm | Mass, g | Volume, cm3 | Density, g/cm3 |

|

| UHMWPE | 40.8 | 18.3 | 22.4 | 23.93 | 0.94 |

| UHMWPE+0.5 wt.% NDC | 40.6 | 17.9 | 21.9 | 23.17 | 0.95 |

| UHMWPE+0.5 wt.% SWCNTs | 40.7 | 19.6 | 24.3 | 25.50 | 0.95 |

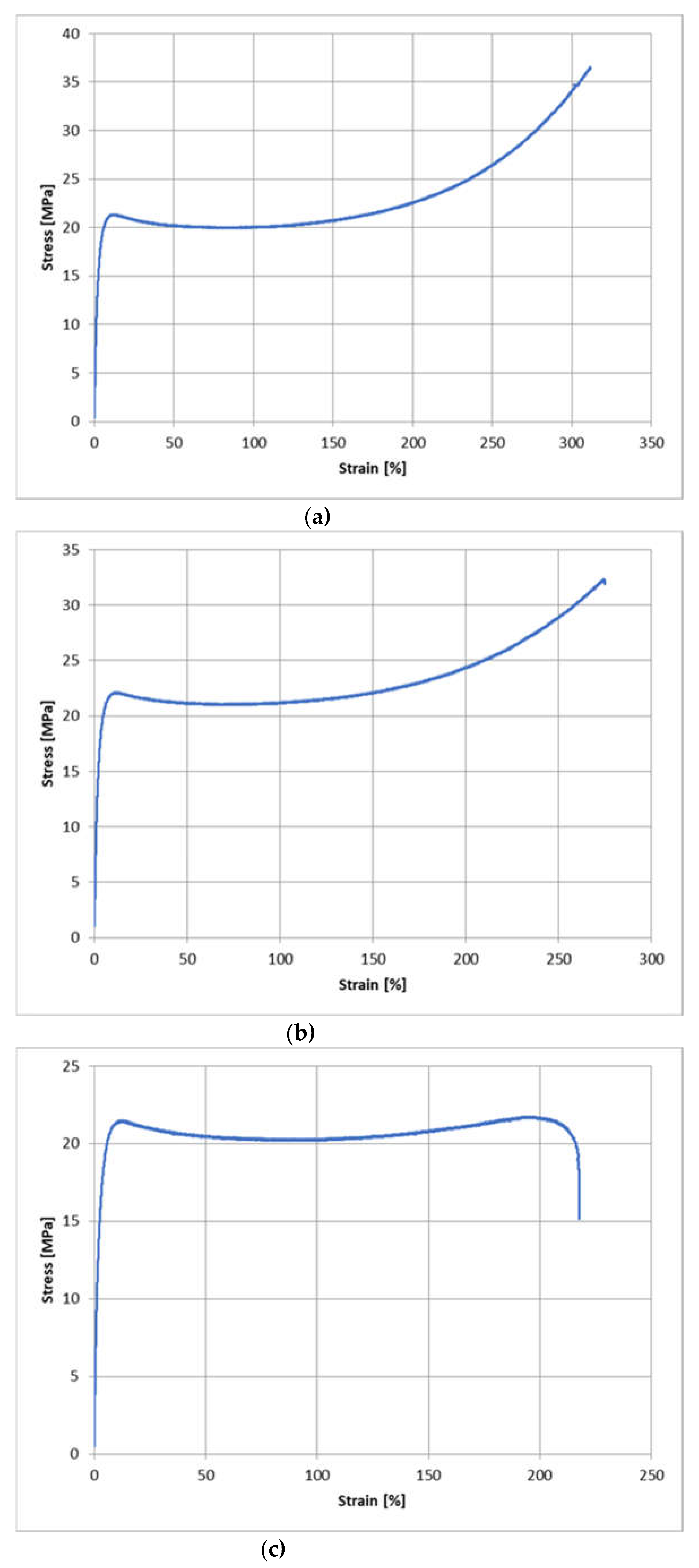

| Material | E, MPa | σ0.2, MPa | σm, MPa | δ, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UHMWPE | 776.2 | 12.2 | 36.6 | 312 |

| UHMWPE+0.5 wt.% NDC | 883.6 | 12.7 | 32.3 | 275 |

| UHMWPE+0.5 wt.% SWCNTs | 767.9 | 12.3 | 21.8 | 218 |

| Material | Wear, mm3 | Сoefficient of friction |

|---|---|---|

| UHMWPE | 0,052 ± 0,006 | 0,10 ± 0,01 |

| UHMWPE+0.5 wt.% NDC | 0,046 ± 0,005 | 0,09 ± 0,01 |

| UHMWPE+0.5 wt.% SWCNTs | 0,032 ± 0,004 | 0,08 ± 0,01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).