1. Introduction

Water immersion is the leading cause of hospitalized non-fatal drownings [

1] and unintentional deaths among children 1–4 years [

2]. The United Nations recently recognized drowning as a global burden of mortality, especially among children, and made an urgent plea to researchers to develop research programs and strategies to understand and prevent drowning. They also recommended the adoption of drowning prevention actions proposed by the World Health Organization [

3]. Both the World Health Organization [

4] and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) [

5] recommend teaching children basic swimming skills as one of several multifactorial actions to prevent drowning. However, the scientific literature does not yet support the effectiveness of swimming programs for the prevention of drowning among children younger than 2 years of age [

6].

Although teaching swimming competencies can reduce the odds of drowning among children 2-4 years of age, infants younger than 2 years of age cannot intentionally control their breathing in order to survive in the water for long periods of time [

6]. In addition to young children’s inability to exit the water by themselves, another possible reason for the overrepresentation of young children in drowning statistics is that when infants become mobile, they are too young to perceive the risks imposed by bodies of water and, therefore, their risk of falling into the water increases [

7].

The AAP initially advised that children should only start swimming programs after the age of 3 years; first because no evidence existed to determine if swimming programs for very young children would impact the likelihood of drowning and, second, because enrolling babies in swimming programs could develop a false sense of security in caregivers and a consequent reduction of proper supervision [

8,

9]. They also expressed concern that baby swimming programs could “reduce a child’s fear of water and unwittingly encourage the child to enter the water without supervision” [

10] (p179). In light of a case-control study showing that swimming lessons did not increase the risk of drowning in 1-4 year-olds [

11], the AAP subsequently changed the recommendation [

10]. They softened their stance stating that swimming programs could be beneficial to children of all ages, including babies, provided other layers of protection against drowning (e.g., constant and capable supervision, effective pool barriers) were in place. Nevertheless, the AAP [

10] made clear that swimming lessons do not promote ‘drown-proofing’ skills in young children. Videos on the internet and anecdotal reports of infants saving themselves from drowning by turning to float on their backs require scientific validation [

12].

A lingering concern is that parents might overestimate their babies’ swimming skills and neglect responsibility for close supervision because their children are enrolled in swimming programs [

8,

9]. Indeed, Morrongiello and colleagues [

13] reported that parents’ judgment of their young children’s swimming skills tends to be poor, even when they are enrolled in swimming programs, and they underestimate their need for supervision. Yet, parents’ overestimation did not increase as their children accumulated swimming lessons. Interestingly, Borioni and colleagues [

14] recently showed that a 10-week swimming intervention for infants provided some positive benefits in terms of general motor development (i.e., gross, fine and total motor skills). Unfortunately, however, this study did not consider the impact that the swimming lessons had on the infant’s behavior around water. To our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated how swimming lessons influence young children’s perception of the risk of entering the water and their resulting behavior around water bodies.

In line with the ecological approach, pioneered by J. J. Gibson [

16] and E. J. Gibson [

17], Burnay and colleagues recently established a novel ecological line of research on infants’ risk perception and behavior that can address some of the aforementioned questions and potentially contribute to the prevention of pediatric drowning (see Burnay et al. [

15]). By understanding the dynamic relationship between infants’ perceptual-motor development and experiences and aquatic environments, we can better understand infants’ adaptive behavior around bodies of water that can lead to drowning incidents.

The ecological approach was first used to investigate infants’ relationship with bodies of water when Burnay and colleagues tested infants’ avoidance behavior on a Water Cliff apparatus (i.e., drop-off leading into the water) and on a Water Slope apparatus (i.e., ramp leading into the water). Focusing on the role of locomotor experience on infants’ perception and action around these risky environments, Burnay and colleagues reported that when infants first start crawling, they tend to fall into the water in the cliff scenario [

18,

19], but after weeks of crawling experience they start to perceive the danger and avoid these falls [

18,

19], even when they start walking [

20]. Burnay and colleagues also showed that when the entrance to a body of water is smooth and gradual, with a slope instead of a drop-off leading into the water, infants’ tendency to venture into deep water increases considerably, but is not linked to locomotor development or experience [

21]. The different findings on the water cliff and the water slope relative to the contribution made by locomotor experience to avoidance behavior highlights the importance of context as a regulator of behavior. They also have important implications for our understanding of drowning in young children and how to prevent it because they suggest young children might be at much greater risk for drowning when they can enter a body of water via a slope than a drop off. Finally, the findings raise the interesting possibility that other experiences that influence young children’s tendency to venture into a body of water might have different effects depending on the nature of the access to the body of water.

The prior work by Burnay and colleagues has established the effect of locomotor experience and the type of access to bodies of water on infants’ perception and action around water. The aim of the present article is to examine to what degree infants’ participation in baby swimming programs influences their perception and behavior around ramps and drop-offs leading into the water. Specifically, this article reports the effect that the number of swimming sessions has on infants’ avoidance of venturing into deep water through ramps and drop-offs and, consequently, on their potential to engage in drowning incidents on these different types of accesses to the water. From an ecological perspective, we predicted that infants who had more swimming lessons would have a greater appreciation of the different actions possible in water and on land. Using the language of ecological psychology, we predicted that infants with more swimming experience would have learned that solid surfaces afford safe locomotion whereas bodies of water do not (at least not for unskilled swimmers). Consequently, we expected to see greater avoidance of the water in the cliff and slope scenarios in infants who had attended more swimming lessons.

4. Discussion

The effectiveness of baby swimming programs on the swimming skills and propensity for drowning in children younger than 2-years of age is not well established in the literature [

6]. Researchers have debated whether baby swimming programs make infants safer around bodies of water by teaching them potential survival skills when they fall into the water or whether they make them less safe by giving them or their caregivers a false sense of confidence around bodies of water. Evidence exists for both sides of the debate. Instead of focusing on the effect of swimming programs on infants’ behavior in the water (i.e., swimming competency or survival skills), the present study investigated the impact of baby swimming programs on infants’ behavior when they approach the water, their perception of the risk and their tendency to venture into the water. Previous studies have shown that locomotor experience influences infants’ avoidance of falling into the water [

18,

19,

20] but has no effect on infants’ avoidance when the water can be entered via a slope [

21]. These prior results did not identify the influence of other factors, such as experience in baby swimming programs, on water avoidance. However, they did foreshadow the current findings by showing that a particular type of experience made a significant contribution to infant’s avoidance behavior in one context, when the infant could access the water via a drop-off, but made no contribution to avoidance behavior in another context, when the infant could access the water via a slope.

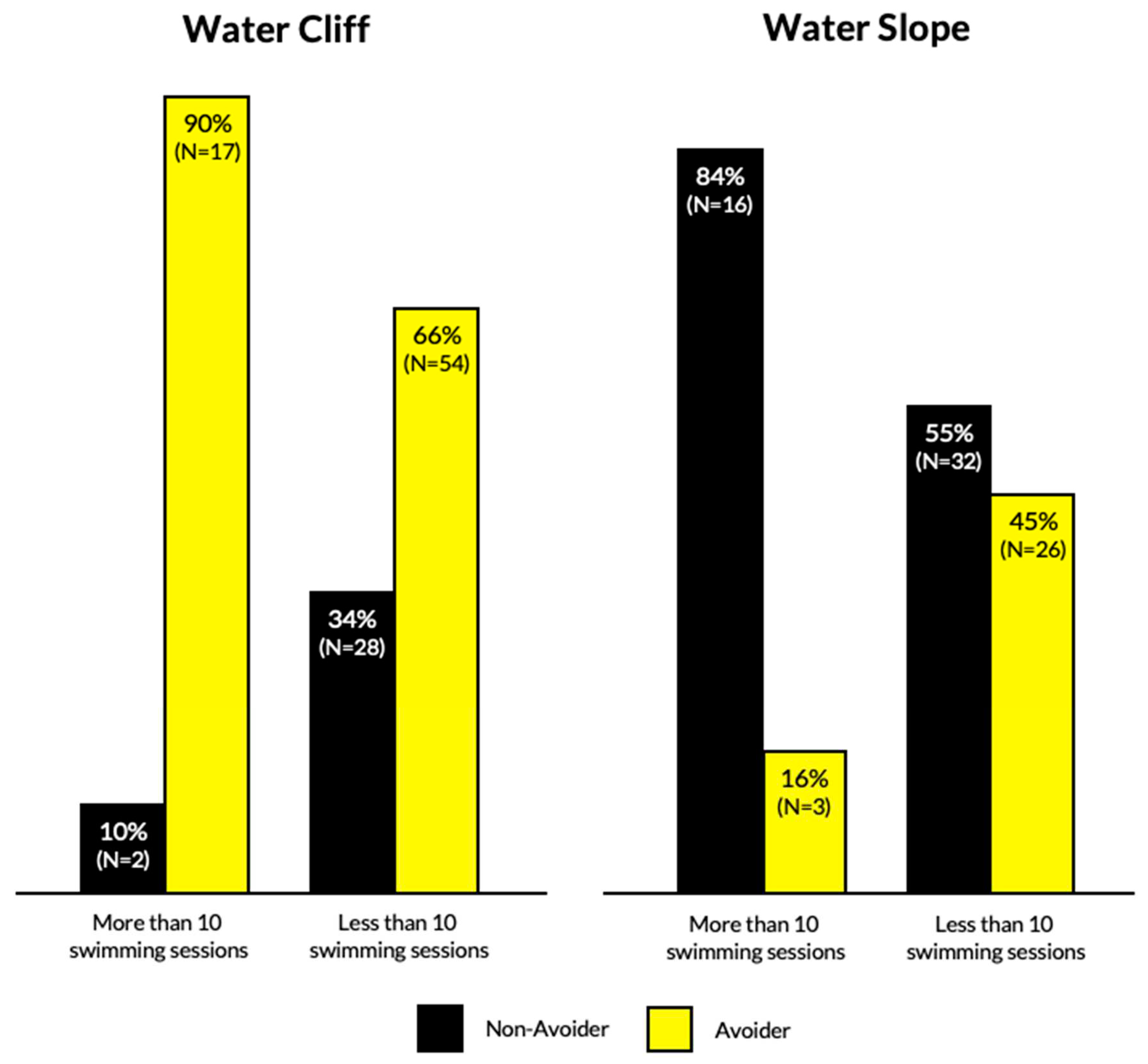

The present analyses of the impact of baby swimming programs on infants’ perception and action around bodies of water showed no effect of the total number of swimming sessions attended on infants’ avoidance of drop-offs (WC) or slopes (WS) leading into the water. When comparing infants that attended more or less than ten swimming sessions, we found a marginal effect on infants’ avoidance on the WC (p = 0.052) and a significant effect was observed on infants’ avoidance of the WS (p = 0.030). These findings were supported by a significant interaction between the type of entrance to the water and the number of swimming sessions attended on infants’ avoidance behavior. Of the infants who attended more than ten swimming sessions, 90% avoided the WC whereas only 38% avoided the WS. These data appear to support the assumption that baby swimming programs have a positive impact on infants’ perception and action around drop-offs leading into the water but an opposite effect when a sloped surface offers access to the water.

A possible explanation for these results is the potential differences in the perception of the affordances (i.e., possibilities for behavior, see Gibson [

22]) in the two scenarios. As previously established in the literature, a drop-off does not afford safe locomotion and locomotor experience teaches infants to avoid drop-offs [

23], whether they lead into the water or not [

15]. It appears that the experience in baby swimming programs can enhance this perception of the risk of falling into the water acquired through locomotor experience. Perhaps the swimming lessons enhance the salience of the distress associated with a sudden plunge into the water or the swimming lessons highlighted the differences between the affordances provided by solid surfaces and water—one affords safe locomotion and the other does not—when an abrupt transition separates land and water. On the other hand, a shallow slope affords safe locomotion [

24], and infants tend to locomote down one even when it leads into the water [

21]. Infants might have much greater difficulty differentiating the affordances provided by solid surfaces and water when the two merge into each other gradually, as with a slope leading into deep water. Young children and even adults have a difficult time discriminating affordances when the boundary conditions between affordances are subtle [

25]. Another possibility is that perhaps infants perceive water as a medium that affords exploration and play when they have attended ten or more swimming sessions and can immerse themselves into it gradually or under their own volition. The perception of the affordances for exploration and play might overwhelm the perception of the affordance for safe locomotion.

As initially proposed by the AAP [

8], the current findings suggest that baby swimming programs may increase the risk of drowning among young children, but not in our opinion because they offer caregivers a false sense of security and overconfidence of their babies’ swimming skills, an argument later dismissed by Morrongiello et al. [

13] Instead, we suggest that experience in baby swimming programs may offer infants’ a false sense of confidence and security to explore the aquatic environment that leads them to risk going deeper and deeper into the water only when the access is smooth, gradual and affords playful interaction. However, the same baby swimming programs may promote a safer approach to the water if the entrance is sudden and less enticing.

Nevertheless, these initial results need to be interpreted with caution and cannot be extrapolated to the general population due to limitations. Infants tested on the WC were from Lisbon, Portugal, and infants tested on the WS were from Dunedin, New Zealand. These differences suggest at least two potentially profitable lines of future research to help untangle the factors contributing to the current findings. First, researchers could explore whether variations in attitudes towards risk taking or child rearing increase risk aversion in Portuguese infants and decrease risk aversion in infants from New Zealand to confirm or rule out a cultural explanation for the current findings. Cultural differences in child rearing deserve serious attention given prior research showing disparities exist in drowning mortality rates in some countries as a function of race and ethnicity [

26]. Children identified as racial and ethnic minorities have a much greater likelihood of dying from drowning than other children [

26,

27]. The World Health Organization calls for further investigation on the contribution of swimming experience and ability in the water to the disparities observed in the risk of drowning among racial and ethnic groups, recognizing that these contributing factors are poorly understood and mainly speculative [

7]. It remains plausible that cultural differences in risk taking or encouragements given to children during child rearing make a contribution to drowning fatality rates.

The second potentially profitable line of future research to help untangle the factors contributing to the current findings involves determining whether the content of baby swimming programs differ in Portugal and New Zealand. Differences might exist in the locations baby swimming programs take place (e.g., open water vs. pool, deep pool vs. shallow pool, pool with vs. pool without sloped accesses), strategies taught to enter and exit the water, if the methodologies encompass drowning safe rules, whether infants experience complete submersion, and the age at which lessons begin, to name a few. Such differences could in turn explain differences in risk aversion between the two groups of infants. Of course, the combination of cultural differences in attitudes toward risk taking in young children combined with differences in the content of baby swimming programs could together explain differences in risk aversion between the two groups of infants in the current study better than either factor alone.