1. Introduction

Humans use mental shortcuts (cognitive biases) to facilitate the decision-making process (Gilovich, 2002), and they are also susceptible to emotional biases (Shefrin & Statman, 1985). These biases are an inclination towards errors as they result in a deviation between an individual's subjective intentions and objective reality, an inevitable aspect of decision-making. The errors resulting from these deviations from traditional theories have garnered significant attention in behavioral finance research, particularly in the context of investment decisions (Bhattacharya et al., 2012). Numerous studies, such as Odean (1998); Garvey & Murphy (2004); Aspara & Hoffmann (2015); Koestner et al. (2017), have demonstrated that these errors stemming from biases can lead to substantial reductions in investment returns. However, many individuals are unaware of the influence biases have on their decision-making and find it challenging to control or avoid them consciously. In this study, we specifically focus on two biases—the disposition effect (an emotional bias) and anchoring bias (a cognitive bias)—and examine their impact on portfolio performance.

The disposition effect and anchoring bias are widely recognized as two highly influential and robust biases that significantly impact investors' decision-making. The disposition effect, initially described by Shefrin and Statman (1985), refers to the tendency of investors to hold onto losing securities for longer periods while selling winning securities too early. On the other hand, anchoring bias, as proposed by (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), refers to the tendency of individuals to rely on initial information, such as reference points, when assessing the value of gains and losses for decision making purposes. Several researchers, including Odean (1998), Weber & Camerer (1998b), Grinblatt & Keloharju (2001), Feng & Seasholes (2005), and Frazzini (2006), have demonstrated that investors rely heavily on anchors such as purchase price, past traded prices, and previous high/low prices when making investment decisions. However, these studies have not explicitly measured the effect of anchoring on investors' trading decisions. Consequently, the first purpose of this investigation is to determine the impact of the disposition effect and anchoring bias on the trading decisions made by our experimental subjects (Indian individual investors) in the simulated investment games.

The existing body of research on the disposition effect in laboratory asset markets has predominantly focused on simulated fictitious assets (Weber & Camerer, 1998; Chui, 2001; Da Costa et al., 2008; Rau, 2014; W. R. Prates et al., 2017). However, there is currently a lack of experimental studies specifically examining anchoring bias within a simulated financial asset market. Furthermore, these assets exhibit varied performance in different market conditions, such as bear, bull, volatile, and stable markets. Consequently, investors' beliefs, risk preferences, and trading decisions vary depending on the asset class and market volatility, thus influencing the behavioral biases observed. To address these research gaps and gain insights into behavioral biases within a more realistic laboratory setting, our second objective is to investigate these biases by having participants hold real assets with varying levels of market volatility in a simulated investment game. Additionally, we explore the influence of behavioral biases on investors' portfolio performance as our final objective.

This study employs a quasi-experimental design to establish a causal interpretation by ruling out reverse causality(Antonakis et al., 2014). It also offers a controlled environment that can help us better understand the emergence of decision biases. Our research design is inspired by Braga & Fávero, (2017) to develop investment games that simulate profit and loss scenarios across different market scenarios. Subjects are tasked with deciding whether to sell or hold securities from both stable and volatile asset markets, and contrast the impact of these decisions in volatile and stable market conditions within a simulated asset market. The main results of the study are threefold. Firstly, we observe the presence of the disposition effect and anchoring bias among individual investors in India. Second, market scenarios or volatility can influence the investors’ behavioral biases. The disposition effect was more prominent in volatile markets and the total market, while the anchoring bias was significant in stable and total markets. This indicates that different market conditions can shape and amplify behavioral biases. Last, Investors prone to the disposition effect tended to have lower portfolio performance, while those exhibiting anchoring bias demonstrated relatively better performance. Our research paper contributes to the nascent experimental literature on behavioral biases and investment decisions in several significant ways. Firstly, it provides valuable insights into how market volatility influences the level of individual-level behavioral biases in their trading decisions. Secondly, our study extends the current literature by examining the impact of behavioral biases on investors' portfolio performance. By investigating the relationship between biases and performance, we provide valuable insights into the practical implications of these biases in real-world investment scenarios. Furthermore, our study introduces a novel methodology for measuring anchoring bias in investors' trading decisions. The findings of our study can assist individual investors in recognizing their own behavioral biases, enabling them to make more informed trading decisions and ultimately improve their portfolio performance. The findings of this study have practical implications for financial institutions and regulatory government agencies that are involved in conducting similar experiments aimed at improving financial decision-making and investment behavior.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The second section provides a review of the literature and related hypotheses. The experiment design is described in

Section 3.

Section 4 reports the results,

Section 5 presents the reliability and validity of the study, and

Section 6 discusses the findings, and the final section concludes with research implications.

2. Literature Review

Our paper relates to investigations on the disposition effect, anchoring bias, and portfolio performance studies. Therefore, we examine the pertinent literature in these fields. We begin with experiments on the disposition effect, then proceed to anchoring bias, and conclude with studies on investment performance.

2.1. Disposition Effect

The term "disposition effect" was coined by Shefrin and Statman (1985). Investors in the stock market often make the mistake of selling a winning stock too soon and holding on to a losing stock for too long. Since its discovery by Shefrin and Statman (1985), the disposition effect has been confirmed in a wide range of experimental and real-world economic contexts. It has also been replicated for numerous countries and categories of investors, including professional and novice investors. We restrict our discussion to experimental studies on the disposition effect to conserve space.

There is substantial experimental evidence for the emergence of disposition effect. Weber & Camerer (1998a) conducted the first study through an experimental method to test the disposition effect using purchase price and the last price as a reference point. Subjects were asked if they could buy and sell six risky assets. The results revealed a disposition impact, with 40% of selling orders for losing and 60% for winning stocks. Chui, (2001) applied the setting of Weber & Camerer (1998)’s design with some modifications, such as the penalty for investors with low trading performance, testing belief in the mean reversion hypothesis, and checking psychological factors and the locus of control to explain the disposition effect. Chui found that belief in mean reversion does not affect the disposition effect and observed that internal locus of control has more pronounced disposition effects. Subsequently, studies establish the relationship between the disposition effect and investors' characteristics such as gender (Da Costa et al., 2008; Rau, 2014; Braga & Fávero, 2017; Cueva et al., 2019), experience (Dhar & Zhu, 2006; Da Costa et al., 2013) and various activities & interventions (Rau, 2015; Bulipopova et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2022).The aforementioned investigations into the disposition effect have primarily focused on countries like the United States, Europe, and parts of Asia, particularly China. These countries have well-developed financial markets and a higher level of financial literacy among investors. Emerging nations, such as India, have experienced rapid economic growth despite having less sophisticated financial markets and lower levels of financial literacy (Agarwalla et al., 2015). In addition, emerging markets such as India are more vulnerable to market volatility, mispricing, and potential market risks (Zahera & Bansal, 2018; Gutiérrez-Nieto, 2023). Hence, there is a need to examine the disposition effect in different market scenarios. Furthermore, previous research has shown that disposition affects younger, naive, and inexperienced investors more (Da Costa et al., 2013; Dhar & Zhu, 2006). In fact, India has a large, dynamic and young population with 65% of Indians under 35 years old. According to a Sequoia capital survey, 70% of new demat account holders are youthful, first-time investors. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct research on the disposition effect in emerging markets like India. Thus, the following is our initial hypothesis:

H1a: The disposition effect impacts the trading decision of Indian individual investors.

On average most experimental studies on the disposition effect are focused on fictitious assets whose price movements and magnitude are determined by stochastic processes with fixed probabilities. Most of the experimental studies have applied Weber & Camerer's design. This design is less realistic than simulated investment games based on historical prices. The latter design resembles a real-world investment decision-making process, enabling researchers to capture the complexities and dynamics of actual market movements, including volatility, trends, and correlations between different assets. But a few studies (Da Costa et al., 2013; Braga & Fávero, 2017; Guenther & Lordan, 2023) have devised an experiment based on simulated investment games. However, the effect of market volatility on disposition has not been investigated. Evidence shows that investors' risk preferences and beliefs change in response to market conditions (e.g., Odean, 1998; Kaustia, 2010; Ben-David & Hirshleifer, 2012). Previous studies have demonstrated that the disposition effect is not uniform and varies with market conditions. Researchers have found that investors are more risk-averse during bust periods, leading to a greater inclination to realize gains (Cheng et al., 2013; Bernard et al., 2021). Investors exhibit a more substantial disposition effect in response to extreme losses than moderate losses (Grinblatt & Keloharju, 2001). Moreover, according to a study by (J. S. Lee et al., 2013), investors are more likely to redeem their mutual fund units during bear markets than bull markets, reflecting a higher propensity to sell investments during periods of market decline. However, recent literature has not compared individual-level disposition effects across different market scenarios (volatile and stable markets). Our study tries to fill this gap by checking whether market volatility impacts the disposition effect.

H2a: Indian individual investors exhibit a stronger disposition effect in volatile market scenarios compared to stable market scenarios.

2.2. Anchoring

Anchoring bias was first identified by (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974) in their laboratory experiment as an anchoring and adjustment bias in which people tend to rely heavily on the first piece of information (anchor) they receive and adjust insufficiently to make final decisions. Anchoring bias has been extensively studied in every domain. In finance, there are two strands of literature related to anchoring bias. The first strand empirically examines the existence of anchoring bias in different financial asset markets. Studies (George & Hwang, 2004; Li & Yu, 2009; Li & Yu, 2012; and Hao et al., 2016) have found substantial evidence of anchoring bias in the stock market, with the 52-week high serving as a significant anchor. Proximity to the 52-week high has been shown to enhance the predictive power of past returns in forecasting future returns. In the art market, (Bian et al., 2021)discovered that past auction prices act as anchors for bidders and auctioneers, influencing decision-making processes. Anchoring bias has also been observed in other markets, such as the foreign exchange market (Westerhoff, 2003), money market (Campbell & Sharpe, 2009), and real estate market (Bucchianeri & Minson, 2013; (Chang et al., 2016)). While substantial evidence exists in these markets, the focus of our discussion will be limited to the literature on anchoring bias in the context of investment decision-making (a second strand of literature), as it aligns with the objective of our study.

The second strand of literature discusses how anchoring bias influences investment decisions. Experimental research on this phenomenon is scarce. Brooks (2011) found that investors attached to a firm's recent "high" will buy the stock when it falls because they think it's a bargain. (Goetzmann & Peles, 1997) found that mutual fund investors prefer high-performing funds. Studies also examined the effects of investors' gender and experience on anchoring bias. Professionals estimate long-term stock returns with less anchoring than undergraduates (Kaustia et al., 2008). Laryea & Owusu (2022) observed that female investors are more likely to be influenced by anchors than male investors. Most anchoring effect experiments are poorly designed. Given studies have been confined to queries like “What do you believe is the current return on the 91-day Treasury bill? (Clue: less than 5%); estimate the 20-year stock return? (Clue: 10% correct historical return). Investors face complex decisions when investing in financial markets, such as choosing between mutual funds, equities, or bonds, and deciding which specific investments to make, and when to buy and sell them? These decisions require significant time and intelligence. Research has shown that humans tend to use mental shortcuts when making complex decisions. In this study, we explore the impact of anchoring bias on minor yet significant investment decisions, specifically the decision to sell a security.

People always make decisions based on a comparison of alternatives across various dimensions. Consequently, all decisions are comparative in nature. Investors often rely on reference points to determine whether to sell a security. The most commonly used reference point is the purchase price of the financial asset. Various studies in behavioral finance have highlighted the importance of purchase price as a reference point, including the works of Shefrin and Statman (1985), Odean (1998), Weber and Camerer (1998), Grinblatt and Keloharju (2001), Feng and Seasholes (2005), Icf et al.(2004) and Li & Yu (2012). Some studies have also considered previous traded prices and past highest or lowest prices as reference points (Heath et al., 1999; Core & Guay, 2001). These studies focused on how reference points influence investors' decisions regarding winning and losing securities. However, no studies have directly examined the influence of anchoring bias on trading decisions in simulated asset markets. As a result, Hypothesis 4 is formulated to determine if anchoring bias affects investors' selling decisions.

H3a: Anchoring bias impacts the trading decisions of individual Indian investors.

Furthermore, as stated previously, there is substantial evidence of anchoring bias across various financial asset markets. Existing research, however, disregards the impact of anchoring bias on investors' decisions to trade securities in a distinct asset market characterized by varying market volatility. Consequently, the following two hypotheses examine the existence of anchoring bias in the stable market and the volatile market.

H4a: Indian individual investors exhibit a stronger anchoring bias in volatile market scenarios compared to stable market scenarios.

2.3. Behavioral Biases and Investment Performance

In behavioral finance, it has been asserted that biases are costly affairs as they influence investment decisions and subsequently impact investment performance. Empirical research on the disposition effect provides evidence of its detrimental effect on investment performance. For instance, Odean (1998) discovered that selling winning investments led to higher average excess returns in the following year than holding onto losing investments. Similarly, studies by (Wermers, 2005; Icf et al., 2004) found that managers of underperforming funds were reluctant to sell their losing stocks. Another study by (Choe & Eom, 2009)observed a negative relationship between the disposition effect and investment performance, indicating that investors prone to the disposition effect were more likely to experience inferior investment performance in the future. However, Locke and Mann (2005) found no immediate, measurable costs associated with this behaviour.

There is no direct evidence of anchoring bias's impact on investment performance. However, research suggests that anchoring can influence stock prices and investment decisions, as discussed in

Section 2.2. It is important to note that anchoring bias may not always be negative or irrational. It can arise when individuals make incorrect estimates based purely on an anchor or rely solely on it and disregard other pertinent information, resulting in complex decision-making. Scholars maintain that anchoring bias is not the consequence of human irrationality but rather a human resource rationality. They propose that the bias results from a rational trade-off between the time required for adjustment and the cost of the error caused by insufficient adjustment. As a result, the magnitude of anchoring bias can vary based on the cost associated with errors and time-related costs. Therefore, it is difficult to predict if investors who exhibit anchoring bias will necessarily have poor investment performance. The opposite scenario, in which investors who exhibit anchoring bias experience positive investment performance, is also plausible.

Many researchers have conducted empirical studies investigating the influence of behavioral biases on investment performance. However, the issue of endogeneity has become a significant concern in these investigations, posing a challenge to finance research. Endogeneity violates the assumption of exogeneity and makes it difficult to determine whether behavioral biases solely impact investment performance. To overcome this challenge, there is a need to study the impact of behavioral biases in a controlled experimental setting, where external factors can be controlled and the problem of endogeneity can be mitigated. In this study, we employ a quasi-experimental design, explained in detail in the methodology section. Quasi-experiments are considered one of the most effective approaches to control for endogeneity (Reeb et al., 2012).

Moreover, quasi-experiments can provide a strong basis for causally interpreting the results by ruling out reverse causality. Hence, we aim to investigate the impact of behavioral biases on investment performance in a laboratory setting. The following hypothesis is formulated to test the relationships:

H5a: Individuals who exhibit disposition effect in their investment decision-making have lower portfolio performance.

H6a: Individuals who exhibit anchoring bias in their investment decision-making have lower portfolio performance.

3. Experiment Design

3.1. Quasi-experimental Design

A quasi-experimental design allows participants to trade in a simulated market environment in an interactive setting to test the research hypotheses framed to examine the disposition effect and anchoring bias among Indian individual investors. The experiment represents stable markets and volatile investment markets. Trade movements of nifty indices, consumer durable, and pharma represented stable asset markets (stable market). Trade movements of cryptocurrencies, bitcoin, and Ethereum represented volatile investment trades (volatile markets). Market scenarios were created with historical price data (April 2014 to March 2020) of the selected assets.

Participants took part in a virtual quasi-experiment using the Zoom app, where they viewed trade charts of two assets simultaneously using PowerPoint animation. Each asset trade started with a base price of 100 and exhibited 5 successive trade sessions. The simultaneous exhibit of trade sessions is presented as four trade scenarios for each stable and volatile market segment. A total of 16 scenarios were designed with each exhibiting 5 trade sessions. Participants' choice of selling or holding an asset is the data for our study.

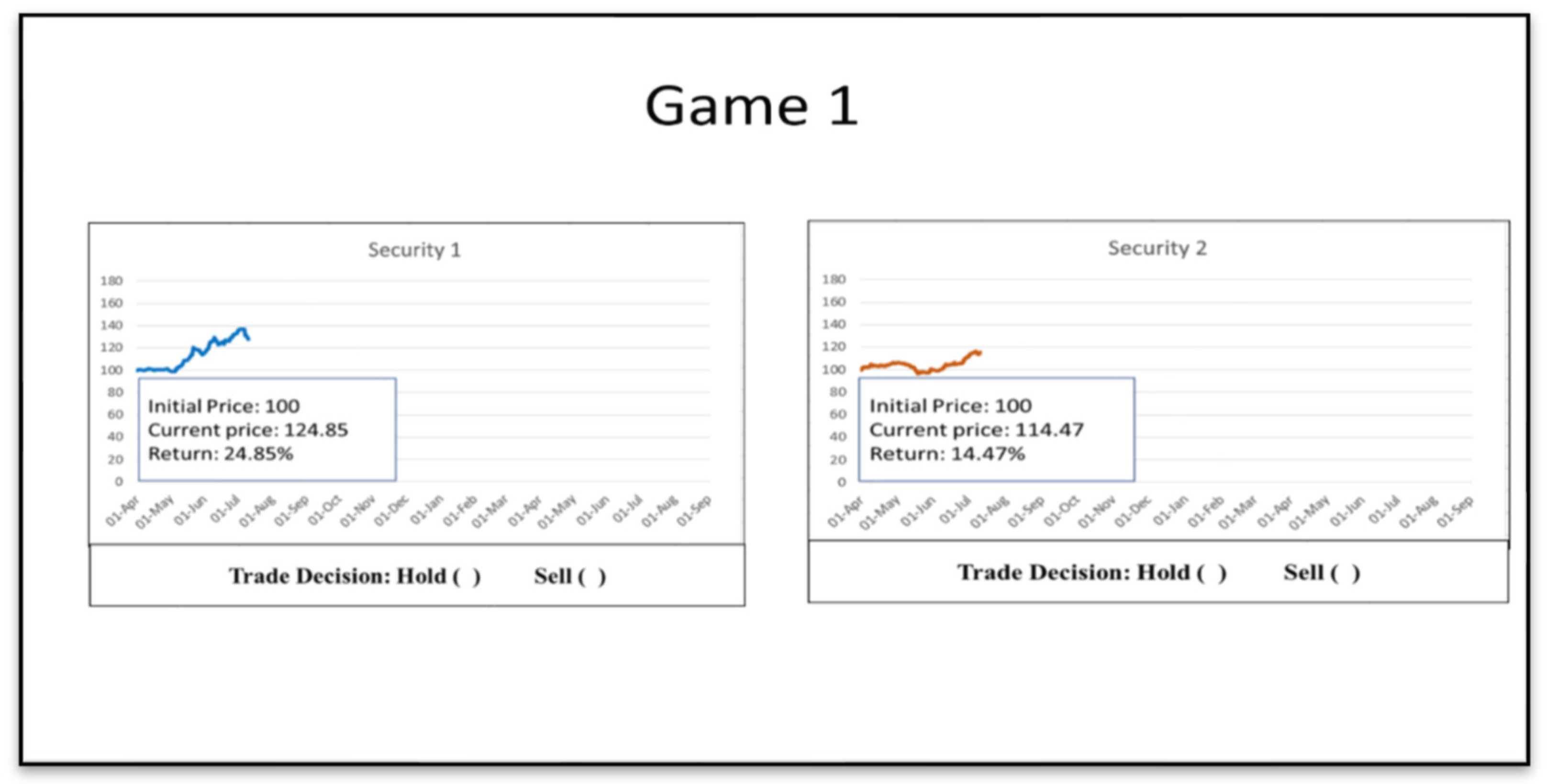

The first trade session (Game 1) in the stable market was designed more as an introduction to familiarize the experiment with the participants. Participants could sell the two assets displayed simultaneously in the games anytime during the trading session (1 to 5) (

Figure 1). Price charts of the two assets were unrelated. Each participant's experiment takes between 25 and 30 minutes to complete.

Participants also filled out a Google form with demographic information and self-established loss tolerance levels. A feedback form elicited the reasoning behind each trading decision.

We divided the games into profit and loss categories based on the final return. The initial price of each security was 100 rupees. We classify a game as a profit game if the price of the security at the fifth trading decision is greater than 100 and as a loss game if it is less than 100. Games are considered stable when price variation (standard deviation) falls below 20%; otherwise, they are considered volatile. Using this method, we classify games to depict the market's volatility and stability. The first table provides a summary of 16 investment games. The initial pair of games, G11 and G12, were used to familiarize subjects with the games. The games G21, G31, G41, G52, G61, and G81 were profitable, while the remaining games were losses. The games from G11 to G42 were classified under stable market category, as their average standard deviation in both profit and loss games was below 20%. On the other hand, the games from G51 to G82 were categorized as volatile asset market games, exhibiting higher volatility. These volatile games had average standard deviations of 127.86% in profit games and 42.31% in loss games (refer to

Table 1).

Convenience sampling method was chosen to ensure the participants' involvement in the experiment. One advantage of taking convenience sampling is getting subjects of diverse socio-demographic attributes.

Table 2 shows details of the subjects. Our subjects contain 14 males and 24 females, which accounts for 35% and 65% of the subject’s population, respectively. Among the subjects, 45% are low-income, while 55% are high-income category. Regarding "employment," 57.5% of the subjects are employed, while 42.5% are unemployed and are Ph.D. and master's degree students. In terms of experience, 28% of respondents have more than two years of stock market exposure, while 72% have less than two years of experience.

3.2. Measurement of Disposition effect.

We apply Odean's (1998) measure, known for its robustness in capturing market cycles and varied market scenarios. The presence of the disposition effect can be determined by calculating the difference between the proportion of gains realized (PGR)and proportion of losses realized (PLR) by an individual investor (i). The proportion of gains realized (PGRi) and proportion of losses realized (PLRi) are computed as

where RG

i (RL

i) is the number of trades by investor i with a realized gain (loss), and PG

i(PLi) is the number of potential trades for investor i with a gain (loss).

The extent of the disposition effect depends on the difference between PGR and PLR. This method corresponds to a series of actions. Each investor's market portfolio comprises stocks held for gains and those held for future trade. Finally, we calculate the PGR and PLR after analyzing the consequences of each selling decision. In this study, we modified the formula by including the time factor (early versus late) alongside realized gains, realized losses, and paper losses. If the subject sells the security in the first three trading decisions (1–3), the sales are considered early; otherwise, they are considered late. Thus, the new formula would be the difference between proportion of realized gains early (PRGE) and proportion of realized losses early (PGLE). The equations are stated below:

If PGREi is greater than PLREi (PGREi > PLREi), the disposition effect is present. If PGREi is equal to PLREi (Prey = PLREi), the disposition effect is absent. If PGREi is less than PLREi (PGREi < PLREi), the reverse disposition effect is verified.

In addition, we use a second metric to evaluate the robustness of the initial metric. We assess the average holding time to realise losses (AHTL) and the average holding time to realise gains (AHTG) based on the definition proposed by Shefrin and Statman (1985). The disposition effect occurs when investors hold onto losers for too long and sell winners too soon. In accordance with the specification, the disposition effect is computed by subtracting average holding time to realise losses (AHTL) from average holding time to realise gains (AHTG).

By employing these measures, we intend to assess the disposition effect comprehensively, considering both the comparison of early gains and losses and the average holding times for gains and losses.

3.3. Measurement of anchoring bias

Our study aims to detect anchoring bias by contrasting how people react to winning and losing in two games. The conventional belief is that because anchoring bias is anticipated to "draw people's estimates closer to the anchor," responses of individuals in the treatment group should be closer to the anchor than responses of individuals in the control group. Given the information provided, our experiment's treatment group and control group are interchangeable. The profit game's treatment is the previous high price, while the loss game's treatment is the previous low price.

Based on the work of (Kaustia et al., 2008), we develop a novel method for identifying anchoring bias in our research. In our experiment, participants simultaneously play a profit game and a loss game. We use the previous highest price as an anchor in the profit game because it may influence participants' selling decisions. Similarly, the previous low price is used as an anchor in the loss game because it may affect the selling decisions of participants. Prior research has demonstrated that price peaks and troughs are significant market anchors. On this premise, we hypothesize that investors' selling decisions in profit games will be influenced by the previous high price, prompting them to sell when the current price approaches it. There are two instances in which the selling price of the subject is closer to the anchor. It can either be nearer or higher than the anchor or nearer or lower than the anchor. We compute the Anchoring Index (AI) by subtracting relative difference of profit games (RDPGi) from relative difference of loss games (RDLGi) for investors to quantify anchoring bias.

The AI index may take on any value from - infinity to +infinity. If there is no anchoring bias in the investor's judgment, the value of AI will be 0. If the value of the AI is positive, indicating the investor is influenced more by the high price in the profit game than the low price in the loss game, and vice versa if the value of AI is negative. In conclusion, to determine anchoring bias, the AI index measures how much an investor's selling choice is influenced by reference points (previous high and low prices) in profit and loss situations.

3.4. Regression model to measure investor's portfolio performance

In this section, a simple ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model is developed in order to examine the impact of disposition effect (DE) and anchoring bias (AB) on the portfolio performance of individual investors (PP), that is,

Individual investors' portfolio performance (PPi) is the dependent variable. We measure portfolio performance by computing portfolio return and portfolio risk. The independent variables are the disposition effect (DE) and anchoring bias (AB). They are measured using the Eqs. (4) and (8). In addition, we include several socio-demographic variables as control variable which consist of gender (C

1), age (C

2), employment status (C

3), and experience (C

4). The control variables are assigning a value of 1if they are female, high-income earners, employed, and highly experienced, and a value of 0 if they fall in the opposite categories. We computed portfolio return (PR

i) and portfolio risk (PRRi) of each individual using the given formulas:

where,

Ws = weightage of each security (i.e., 0.25 for each security)

R

s = total return earned in each security (using the holding return formula)

where,

Ws = weightage of each security (i.e., 0.25 for each security)

RRs = probability of earning returns below the average offered by each security.

We estimate the aforementioned OLS regression equation six times. First, by employing portfolio return as a proxy for portfolio performance risk in stable, volatile, and total market, we expect behavioral biases to have a negative impact on portfolio return. Second, we estimate the equation using portfolio risk as ta volatile for portfolio performance. We anticipate that behavioral biases positively affect portfolio risk across three market scenarios, which means that subjects who exhibit behavioral biases have taken on more risk than those who do not.

4. Results and Findings

The results section begins with identifying behavioral biases (disposition effect and anchoring bias) across various market scenarios. The section concludes with findings from regression analyses that demonstrate the effect of behavioral biases on portfolio performance. All reported tests are based on one-sided p-values if not otherwise specified.

Table 3 shows disposition effect results from two methods across different market scenarios. Using statistical analyses, we examined the difference between PGRE and PLRE and the disposition effect difference between stable and volatile markets. We used two tests, one parametric (Welch's t-test) and non-parametric (Wilcoxon signed rank test) for the distribution of the effect. The disposition effect is present but insignificant in stable market, as the difference between PGRE and PLRE is positive (0.0083). However, DE is positive and significant for volatile market (0.30) and the total market (0.175) from both the statistics. Moreover, the DE in the volatile market (0.3) is considerably significantly higher than the DE in the stable market (0.0083) (t stats =2.225 at 5% sig. level; z stats= 3.313 at 1% sig. level). The results replicate using the alternative method (Average holding time period). The disposition effect is positive (0.0083), but the p-value is high (0.436). DE is positive, with a 1% and 5% significance level in the volatile market (0.13) and the overall market (0.07). The volatile market DE (0.13) is significantly higher than the stable market DE (0.0083) from both the statistics. Overall, the results indicate that different market scenarios or market conditions influence investors’ disposition effect.

Table 4 shows anchoring bias across asset markets. The stable market's mean relative difference of all profit games (MMRDPG) is -0.313. On average, subject sells securities below the previous trading highest price compared to the average pooled sample selling security against anchor. However, the positive value of MMRDLG (1.617) indicates that, on average, subject’s selling prices deviate above the previous low price in the loss games compared to the pooled sample. Thus, the Anchoring index calculated by subtracting MMRDPG from MMRDLG is -1.9307 (p = 0.00), indicating that subjects are more influenced by the previous lowest prices in loss games than by the previous highest prices in profit games. In the volatile market, the AI index is positive (0.3920) but not statistically significant, indicating that subjects are more anchored to the previous high prices in loss games than the previous low prices. Similarly, in the overall market, both MMRDPG and MMRDLG have positive values (0.412 and 1.015, respectively). Still, the value of the AI index is significantly negative (-0.603), showing subjects are more anchored to previous lowest prices in losing games than to previous high prices in winning games. The results indicate that investors exhibiting anchoring bias differs according to market scenarios.

Table 5 shows the coefficients from the regression of portfolio return on behavioral biases across asset markets. Negative and statistically significant coefficients (-0.048 for SM at 10% sig, -2.243 for VM at 1% sig, -1.184 for TM at 1%) imply that a stronger disposition effect is associated with lower portfolio return across each asset market. Positive coefficients (0.007 for SM, 0.1181 for VM, and 0.1812 for TM) indicate that a higher anchoring bias is associated with a higher portfolio return. However, this association is statistically significant only in TM at 5%. Moreover, the coefficients of control variables are not statistically significant, indicating that demographic attributes do not affect the impact of behavioral biases on portfolio performance. All the models are statistically significant and a good fit.

Additionally, we can see the effect of behavioral biases on portfolio risk in

Table 6. The results show positive and statistically significant coefficients (0.540 for VM at 1% sig and 0.313 for TM at 1%) that imply that a stronger disposition effect is associated with greater portfolio risk. Investors who exhibit the disposition effect have a higher portfolio risk than those who do not. However, negative coefficients (-0.001 for SM, -0.010 for VM, and -0.017 for TM) indicate that anchoring bias is lower with a higher portfolio risk, but this association is not statistically significant. Again, demographic variables are statistically insignificant in all markets. The overall model is statistically significant fits in the volatile and total market well.

5. Reliability and Validity of the study

5.1. Reliability

The experiment is designed to examine the trade decisions taken in profit and loss scenarios in different markets by comparing the average return percentage of paired games using paired t-test.

Table 7 shows that the asset returns of each market scenario in each game of the participants statistically were different, thus establishing the reliability of the experiment design. The first game is an introduction to familiarize the experiment that has not shown a significant difference in asset returns.

5.2. Validity

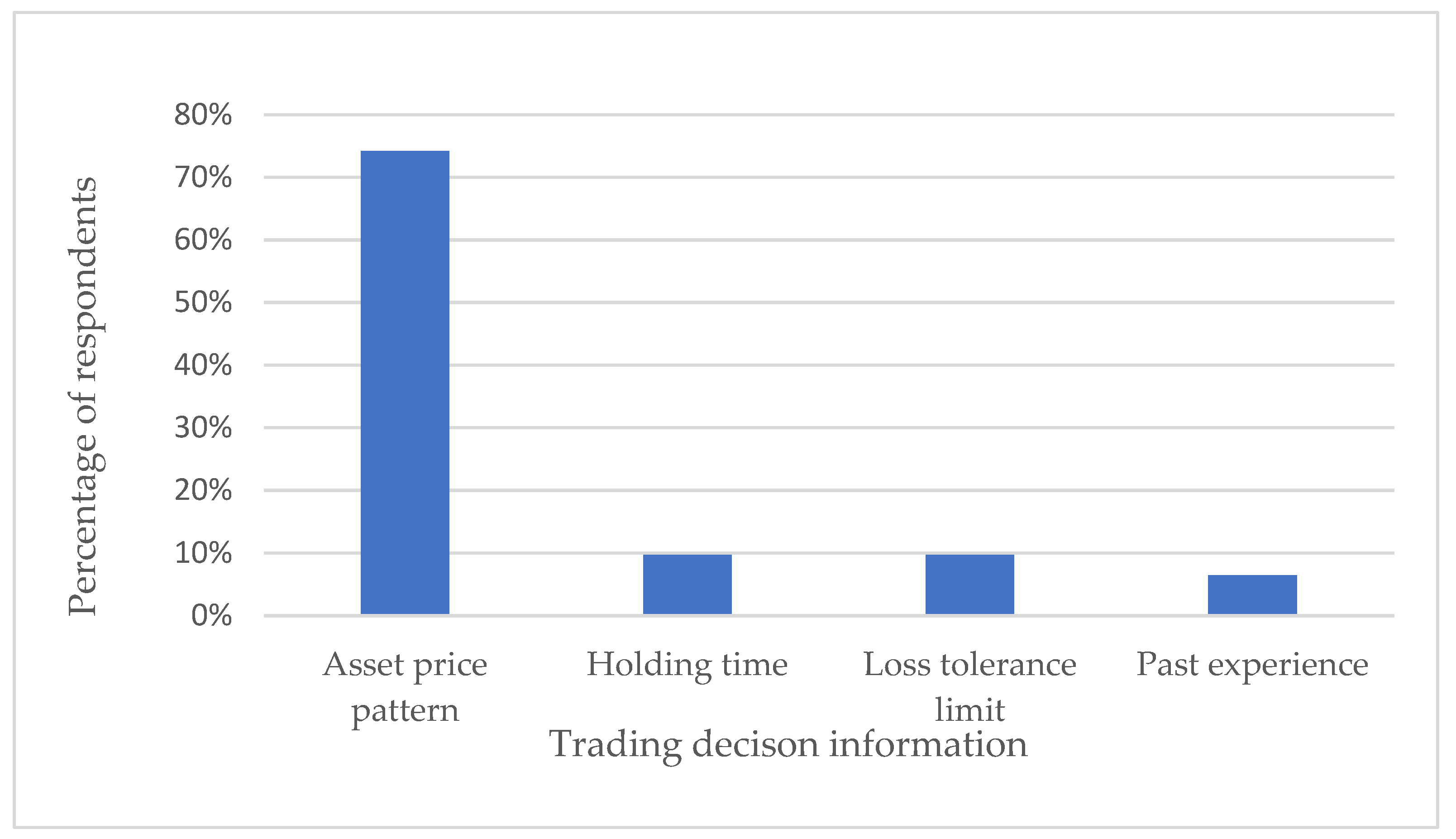

Figure 2 and

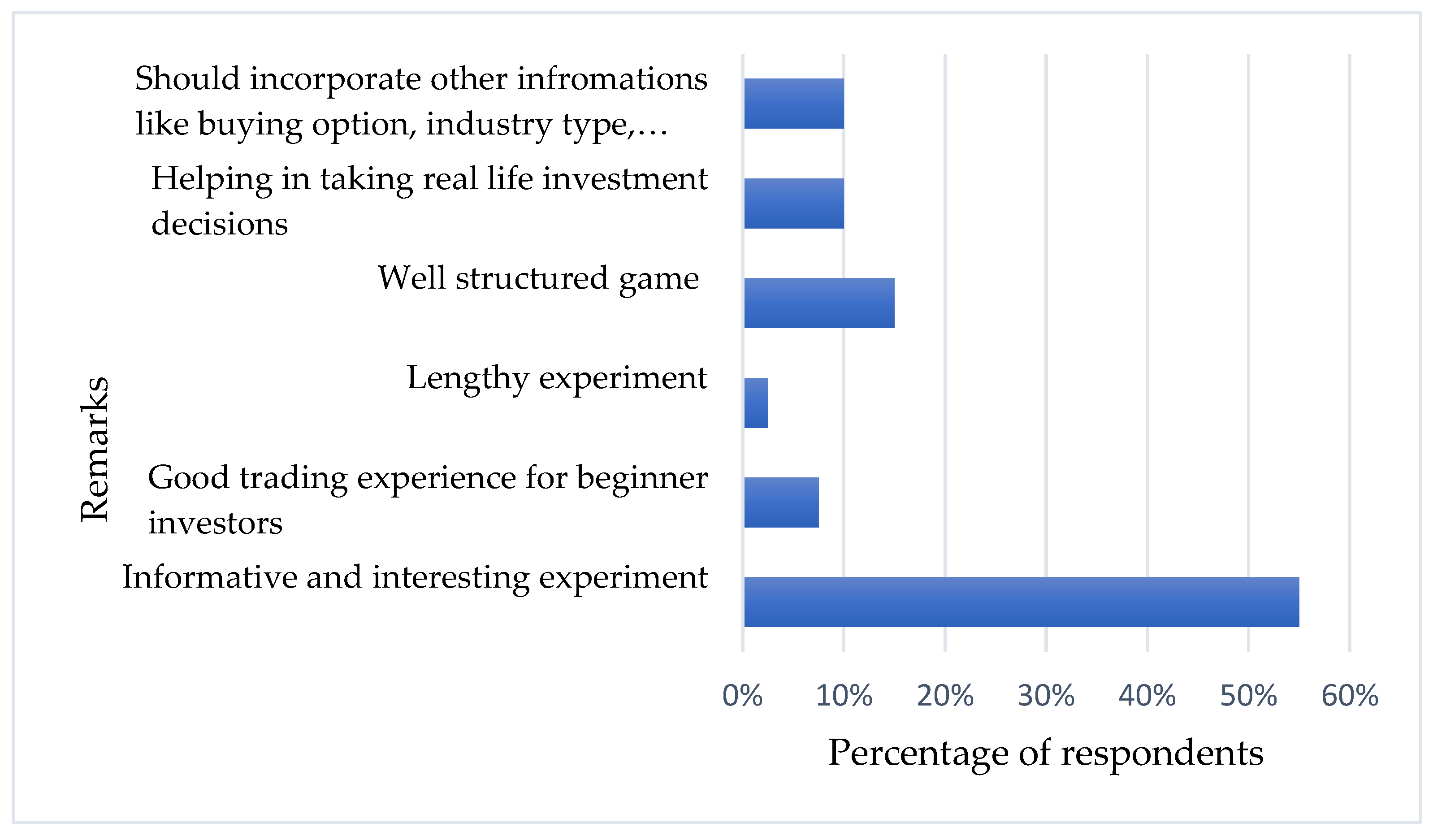

Figure 3 display the results of a feedback form that asks two questions: 1) What information did you use to make your decision? 2) Participants' final remarks about this experiment. Both questions were designed to be open-ended, allowing for a wide range of responses. The first question ensures that the answers were not random but was based on specific criteria by identifying the information base. The second question sought to assess the instrument's face validity. The responses of 40 participants were analyzed using thematic analysis. According to a thematic analysis of respondent responses (

Figure 2), 74% only used asset price pattern information (market price, return, and chart pattern) to trade, around 9 % used holding time, and another 9% considered their loss tolerance limit. The remaining 6% of respondents recalled their experience while making trade decisions. Furthermore, as shown in

Figure 3, 55% of participants said the experiment was informative and interesting, and 15% said it was well-structured, confirming the experiment's face validity. 10% of participants believe that additional information such as purchasing options, market information, and industry type should have been included in the experiment. In comparison, 10% believe this experiment helps make real-world investment decisions, and 7.5% believe it provides a good trading experience for novice investors. The remaining 2.5 percent believe that the experiment is lengthy.

6. Discussion

This section provides a summary and further discussion on the empirical results. The results from

Table 3 present that investors exhibiting disposition effect is highest in the volatile market, followed by the total and stable market. This finding is consistent when using an alternative method to measure the disposition effect, namely the average holding time period of winning and losing securities. There are several plausible explanations for this outcome. First, in volatile market, the frequency and magnitude of price fluctuations are higher, leading to increased opportunities for investors to experience losses. As a result, loss aversion is amplified in volatile markets, making investors more reluctant to realize losses and more inclined to hold on to losing positions. Second, volatile market is characterized by greater uncertainty and perceived risk. Investors may become more cautious and risk-averse during periods of market volatility, leading them to hold on to their existing losing positions. Third, volatile markets can evoke strong emotions, such as fear, anxiety, and panic, which can cloud investors' judgment and subsequently amplify the disposition effect. Lastly, the proxy used to represent stable markets in this study is likely more secure, regulated, and established compared to the volatile market (such as the cryptocurrency market), which has only been in existence for a relatively short period of time. Therefore, market volatility plays a significant role in shaping investors' trading decisions, as they tend to exhibit more rational behavior in stable markets compared to volatile markets, leaving them vulnerable to the disposition effect. Future research could explore the specific factors that have a stronger influence on the presence of the disposition effect in volatile markets compared to stable markets. Our findings contribute to the existing literature by demonstrating that the disposition effect is not uniform and can vary depending on market conditions(Cheng et al., 2013; Bernard et al., 2021). Furthermore, our research contributes to the emerging literature on disposition effect in volatile markets, particularly the cryptocurrency market (Haryanto et al., 2020; Schatzmann & Haslhofer, 2020)

The presence of anchoring bias is notably significant in stable and total markets, as demonstrated in

Table 4. The results indicate that investors are more influenced by the previous lowest price of losing securities rather than the previous highest price of winning securities. This finding suggests that investors tend to anchor their trading decisions to the lowest price levels they have encountered when dealing with losing securities. In volatile markets, investors are influenced more by the previous high price than the previous low price, but this difference is insignificant. Hence, the manifestation of anchoring bias varies depending on market volatility. One possible explanation for the presence of anchoring bias in stable markets, but not in volatile markets, is that stable markets tend to exhibit more predictable and consistent patterns compared to volatile markets. Investors often rely on these historical patterns and use them as anchors when making investment decisions. This reliance on past performance and established patterns can strengthen the anchoring bias, as investors may be hesitant to deviate from the prevailing trends or reference points. Moreover, investors' tendency to anchor their trading decisions to the lowest price levels they have encountered when dealing with losing securities, rather than the previous highest price levels in winning securities, can be attributed to loss aversion and regret aversion. By anchoring their decisions to the lowest price, investors can justify holding onto the security, believing that they will have an opportunity to sell at a more favorable price in the future. Another factor that may contribute to this behavior is mental accounting, as investors often mentally separate their losing and winning securities as distinct entities. This mental compartmentalization reinforces their attachment to the lowest price and influences their decision-making process. Our findings contribute to the existing empirical evidence that investors might anchor on previous high price or low or 52-week high or low when they make investment decisions (Hao et al., 2016; E. Lee & Piqueira, 2019; Bian et al., 2021).

Lastly, the results presented in

Table 5 and

Table 6 examine the impact of behavioral biases on investors' portfolio performance. We find that investors who exhibit the disposition effect tend to have lower portfolio returns and higher portfolio risk. These findings align with existing evidence from studies conducted by (Odean, 1998; Garvey & Murphy, 2004; Aspara & Hoffmann, 2015; Koestner et al., 2017; Choe & Eom, 2009aa ), which have all observed that the disposition effect is a costly behavioral bias. However, our results show the opposite outcome for anchoring bias. Investors who display anchoring bias have higher portfolio returns and lower portfolio risk. These results support the argument put forth by (Lieder et al., 2018; Rezaei, 2021; Laryea & Owusu, 2022) that making decisions based on a reference price may not always be negative or irrational. Furthermore, anchoring bias is not necessarily indicative of human irrationality but rather a result of rational considerations of time spent adjustment and the potential cost of error due to insufficient adjustment. In summary, our findings demonstrate that the disposition effect can be a costly bias for investors, leading to lower portfolio performance. On the other hand, anchoring bias does not necessarily have negative consequences and may even lead to improved portfolio performance. These results shed light on the nuanced nature of behavioral biases and their impact on investment outcomes.

7. Conclusion

The study aims to identify the two most ubiquitous biases in different market scenarios and assess their impact on investors' portfolio performance. To achieve this, a simulated investment game was designed using historical price data from various assets, including equity indices and cryptocurrencies. The main findings of the study are as follows: The presence of both the disposition effect and anchoring bias was observed among individual investors in India. Second, market scenarios or volatility can influence the investors’ behavioral biases. The disposition effect was more prominent in volatile markets and the total market, while the anchoring bias was significant in stable and total markets. This indicates that different market conditions can shape and amplify specific biases. Last, Investors prone to the disposition effect tended to have lower portfolio performance, while those exhibiting anchoring bias demonstrated relatively better performance. For future research, it would be interesting to expand the study by increasing the number of subjects and applying simulation trading to other types of assets that have negative price fluctuations or low positive fluctuations. This would allow for the examination of the role of diversifiers, hedges, or safe-haven assets in an investment portfolio. Also, future studies can investigate investors' behavioral biases in different market trends, such as bear and bull markets. The findings of this research can be valuable for individual investors who seek to understand the behavioral biases that may lead to mistakes in their investment decisions. Investors can minimize risks and improve their investment returns by being more aware of the psychological factors influencing their investment choices. This research may interest financial institutions and government agencies performing similar studies to improve financial decision-making and investment behaviour.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agarwalla, S. K., Barua, S. K., Jacob, J., & Varma, J. R. (2015). Financial Literacy among Working Young in Urban India. World Development, 67(2013), 101–109. [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J. , Bendahan, S., Jacquart, P., & Lalive, R. (2014). Causality and Endogeneity: Problems and Solutions. In The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations. Oxford University Press.

- Aspara, J., & Hoffmann, A. O. I. (2015). Selling losers and keeping winners: How (savings) goal dynamics predict a reversal of the disposition effect. Marketing Letters, 26(2), 201–211. [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, I. , & Hirshleifer, D. (2012). Are investors really reluctant to realize their losses? Trading responses to past returns and the disposition effect. Review of Financial Studies, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, S., Loos, B., & Weber, M. (2021). The Disposition Effect in Boom and Bust Markets. SSRN Electronic Journal, January. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, U., Holden, C. W., & Jacobsen, S. (2012). Penny wise, dollar foolish: Buy-sell imbalances on and around round numbers. Management Science, 58(2), 413–431. [CrossRef]

- Bian, T. Y., Huang, J., Zhe, S., & Zhang, M. (2021). Anchoring effects in the Chinese art market. Finance Research Letters, 43(April), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Braga, R., & Fávero, L. P. L. (2017). Disposition Effect and Tolerance to Losses in Stock Investment Decisions: An Experimental Study. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 18(3), 271–280. [CrossRef]

- Bucchianeri, G. W. , & Minson, J. A. (2013). A homeowner’s dilemma: Anchoring in residential real estate transactions. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. [CrossRef]

- Bulipopova, E., Zhdanov, V., & Simonov, A. (2014). Do investors hold that they know? Impact of familiarity bias on investor’s reluctance to realize losses: Experimental approach. Finance Research Letters, 11(4), 463–469. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S. D., & Sharpe, S. A. (2009). Anchoring bias in consensus forecasts and its effect on market prices. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 44(2), 369–390. 2. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q., Li, J., & Niu, X. (2022). Tempus fugit: The impact of time constraint on investor behavior. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 200, 67–81. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. C., Chao, C. H., & Yeh, J. H. (2016). The role of buy-side anchoring bias: Evidence from the real estate market. Pacific Basin Finance Journal, 38, 34–58. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T. Y., Lee, C. I., & Lin, C. H. (2013). An examination of the relationship between the disposition effect and gender, age, the traded security, and bull-bear market conditions. Journal of Empirical Finance, 21(1), 195–213. [CrossRef]

- Choe, H., & Eom, Y. (2009). The disposition effect and investment performance in the futures market. Journal of Futures Markets, 29(6), 496–522. 6. [CrossRef]

- Chui, P. M. W. (2001). An Experimental Study of the Disposition Effect: Evidence From Macau. Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets, 2(4), 216–222. [CrossRef]

- Core, J. E. , & Guay, W. R. (2001). Stock option plans for non-executive employees. Journal of Financial Economics. [CrossRef]

- Cueva, C., Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I., Ponti, G., & Tomás, J. (2019). An experimental analysis of the disposition effect: Who and when? Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics , 81(July 2018), 207–215. 20 July. [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, N., Goulart, M., Cupertino, C., Macedo, J., & Da Silva, S. (2013). The disposition effect and investor experience. Journal of Banking and Finance, 37(5), 1669–1675. [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, N., Mineto, C., & Da Silva, S. (2008). Disposition effect and gender. Applied Economics Letters, 15(6), 411–416. [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R., & Zhu, N. (2006). Up close and personal: Investor sophistication and the disposition effect. 2014, 52(5), 726–740. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L., & Seasholes, M. S. (2005). Do investor sophistication and trading experience eliminate behavioral biases in financial markets? Review of Finance, 9(3), 305–351. [CrossRef]

- Garvey, R., & Murphy, A. (2004). Are professional traders too slow to realize their losses? Financial Analysts Journal, 60(4), 35–43. [CrossRef]

- George, T. J., & Hwang, C. Y. (2004). The 52-week high and momentum investing. Journal of Finance, 59(5), 2145–2176. [CrossRef]

- Gilovich, T. (2002). Slovic, P., Finucane, M., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2002). The affect heuristic. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment, (pp. 397-420). New York: Cambridge University Press. In The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment (pp. 1–637). http://93.174.95.29/_ads/66B4EF6FB611C97C5F882DC6043AF384%0Apapers3://publication/uuid/87F4C429-EB48-4A34-92A1-2416CE041829.

- Goetzmann, W. N., & Peles, N. (1997). Cognitive dissonance and mutual fund investors. Journal of Financial Research, 20(2), 145–158. 20, 2, 145–158. [CrossRef]

- Grinblatt, M., & Keloharju, M. (2001). What makes investors trade? Journal of Finance, 56(2), 589–616. [CrossRef]

- Guenther, B., & Lordan, G. (2023). When the disposition effect proves to be rational: Experimental evidence from professional traders. Frontiers in Psychology, 14(February), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-nieto, B. (2021). A bibliometric analysis of the disposition effect : origins and future research avenues Cristina Ortiz Luis Vicente Department of Accounting and Finance and IEDIS Universidad de Zaragoza Gran Vía 2 , 50005 Zaragoza , Spain Acknowledgments : This work was . 0–26.

- Hao, Y. , Chu, H. H., Ho, K. Y., & Ko, K. C. (2016). The 52-week high and momentum in the Taiwan stock market: Anchoring or recency biases? International Review of Economics and Finance. [CrossRef]

- Haryanto, S., Subroto, A., & Ulpah, M. (2020). Disposition effect and herding behavior in the cryptocurrency market. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics, 47(1), 115–132. [CrossRef]

- Heath, C., Huddart, S., & Lang, M. (1999). Psychological factors and stock option exercise. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(2), 601–627. [CrossRef]

- Icf, Y., Paper, W., & Frazzini, A. (2004). THE DISPOSITION EFFECT AND UNDER- REACTION TO NEWS The Disposition Effect and Under-reaction to News. LXI(04), 2017–2046. [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 99–127. [CrossRef]

- Kaustia, M. (2010). Prospect theory and the disposition effect. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 45(3), 791–812. [CrossRef]

- Kaustia, M., Alho, E., & Puttonen, V. (2008). How much does expertise reduce behavioral biases? The case of anchoring effects in stock return estimates. Financial Management, 37(3), 391–412. [CrossRef]

- Koestner, M., Loos, B., Meyer, S., & Hackethal, A. (2017). Do individual investors learn from their mistakes? Journal of Business Economics, 87(5), 669–703. [CrossRef]

- Laryea, E., & Owusu, S. P. (2022). The impact of anchoring bias on investment decision-making: evidence from Ghana. Review of Behavioral Finance, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E., & Piqueira, N. (2019). Behavioral biases of informed traders: Evidence from insider trading on the 52-week high. Journal of Empirical Finance, 52(February), 56–75. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. S., Yen, P. H., & Chan, K. C. (2013). Market states and disposition effect: Evidence from Taiwan mutual fund investors. Applied Economics, 45(10), 1331–1342. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., & Yu, J. (2009). Psychological Anchors , Underreaction , Overreaction , and Asset Prices. 612–625.

- Li, J., & Yu, J. (2012). Investor attention, psychological anchors, and stock return predictability. Journal of Financial Economics, 104(2), 401–419. 104, 2, 401–419. [CrossRef]

- Odean, T. (1998). Are investors reluctant to realize their losses? The Journal of Finance, 53(5), 1775–1798. [CrossRef]

- Prates, W. R., da Costa, N. C. A., & Dorow, A. (2017). Risk Aversion, the Disposition Effect, and Group Decision Making: An Experimental Analysis. Managerial and Decision Economics, 38(7), 1033–1045. 1045. [CrossRef]

- Rau, H. A. (2014). The disposition effect and loss aversion: Do gender differences matter? Economics Letters, 123(1), 33–36. [CrossRef]

- Rau, H. A. (2015). The disposition effect in team investment decisions: Experimental evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance, 61, 272–282. [CrossRef]

- Reeb, D., Sakakibara, M., & Mahmood, I. P. (2012). From the editors: Endogeneity in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(3), 211–218. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. (2021). Anchoring bias in eliciting attribute weights and values in multi-attribute decision-making. Journal of Decision Systems, 30(1), 72–96. [CrossRef]

- Schatzmann, J. E., & Haslhofer, B. (2020). Bitcoin Trading is Irrational! An Analysis of the Disposition Effect in Bitcoin. http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.12415.

- Shefrin, H., & Statman, M. (1985). The Disposition to Sell Winners Too Early and Ride Losers Too Long: Theory and Evidence. The Journal of Finance, 40(3), 777–790. [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. [CrossRef]

- Weber, M., & Camerer, C. F. (1998a). The disposition effect in securities trading: An experimental analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 33(2), 167–184. [CrossRef]

- Weber, M., & Camerer, C. F. (1998b). The disposition effect in securities trading: An experimental analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 33(2), 167–184. [CrossRef]

- Wermers, R. R. (2005). Is Money Really “Smart”? New Evidence on the Relation Between Mutual Fund Flows, Manager Behavior, and Performance Persistence. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Westerhoff, F. (2003). Anchoring and Psychological Barriers in Foreign Exchange Markets. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 4(2), 65–70. [CrossRef]

- Zahera, S. A., & Bansal, R. (2018). Do investors exhibit behavioral biases in investment decision making? A systematic review. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 10(2), 210–251. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).