Submitted:

01 July 2023

Posted:

04 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

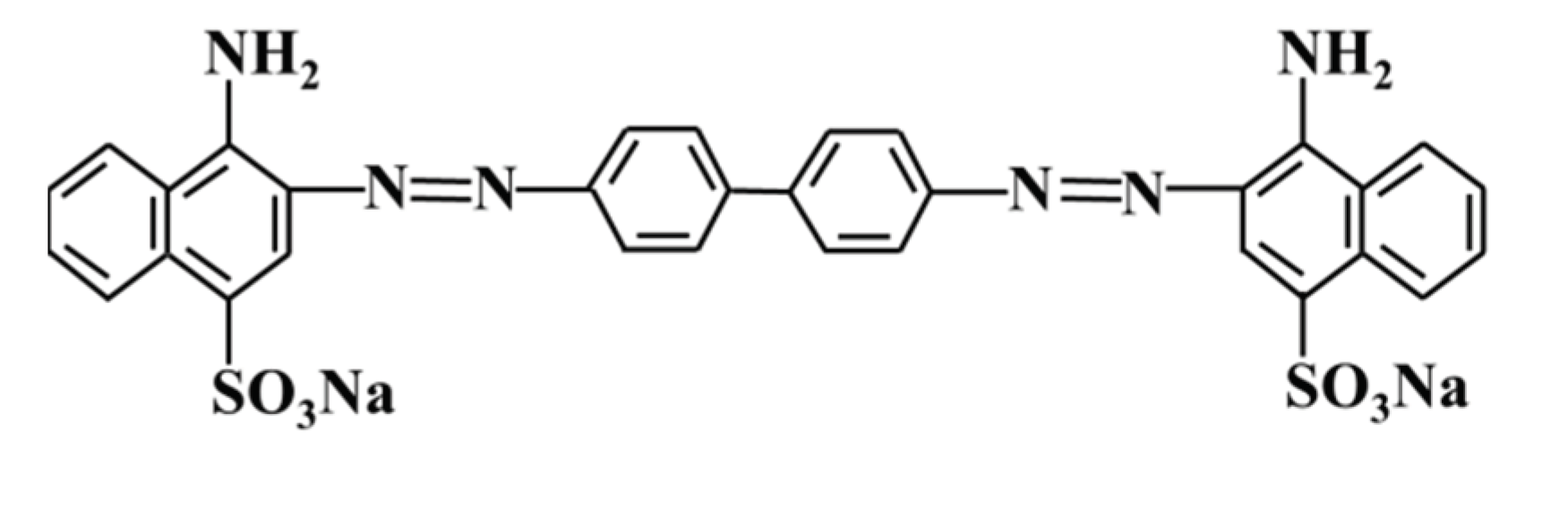

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental procedure

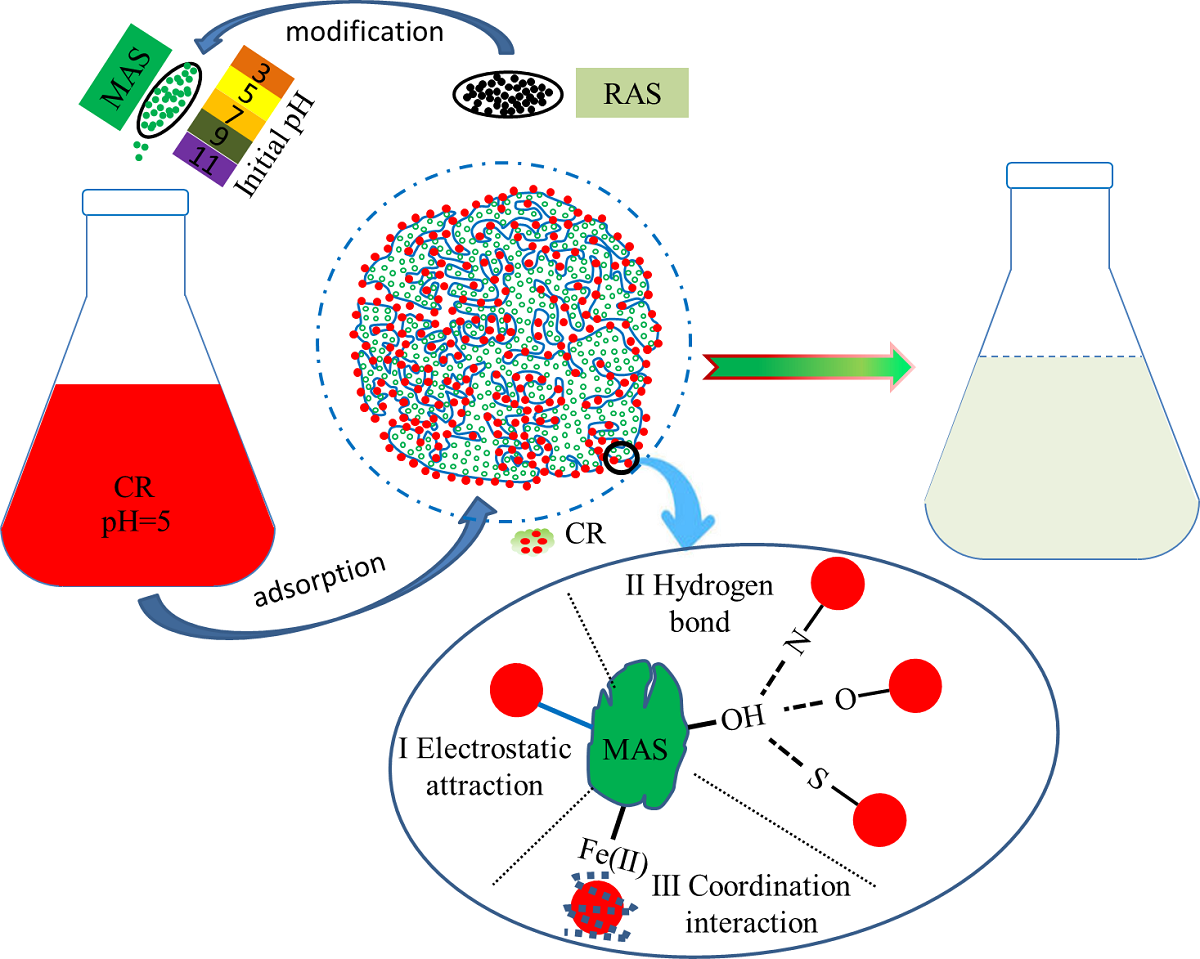

2.2.1. Preparation of MAS

2.2.2. MAS adsorption experiment on CR

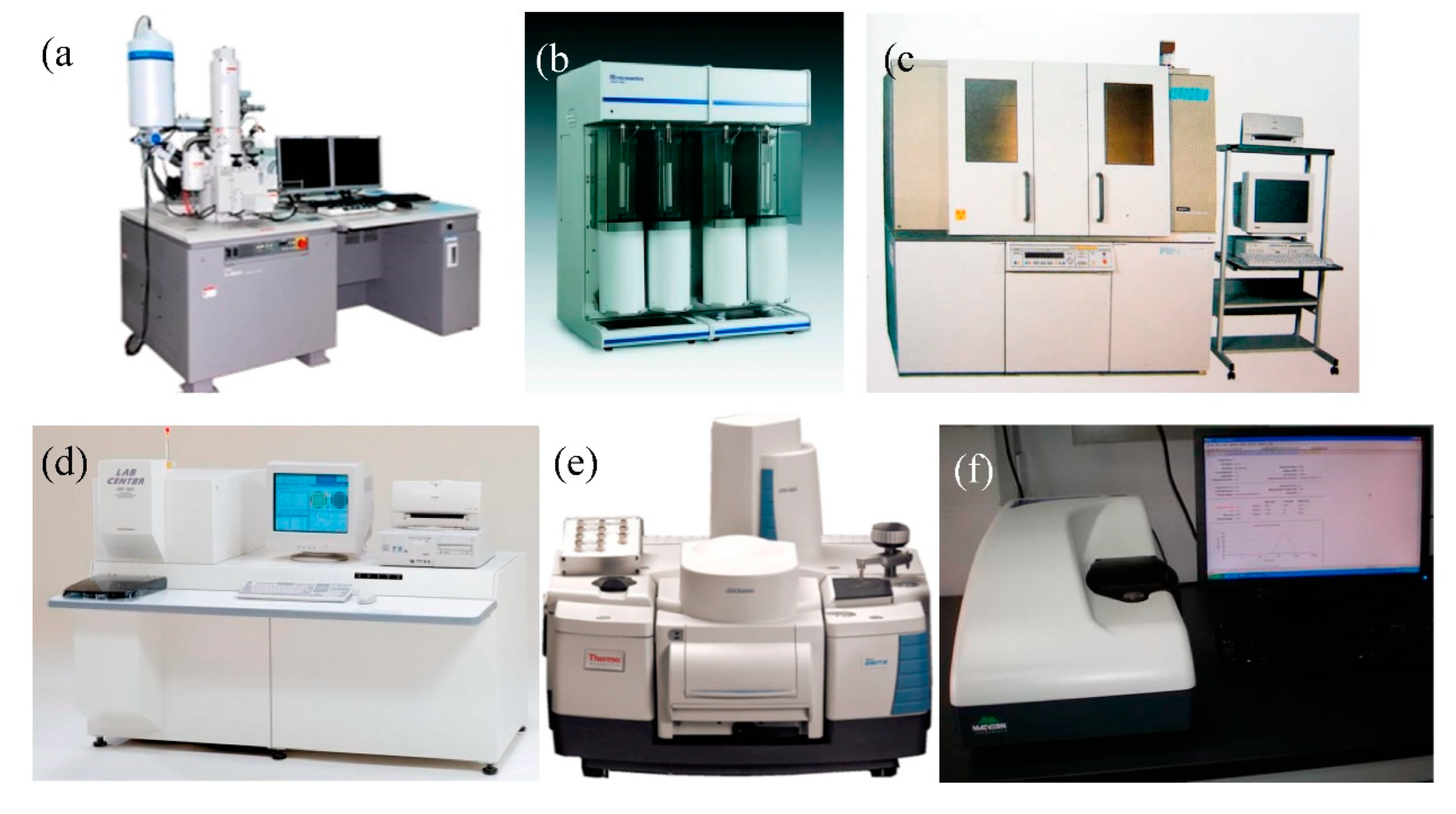

2.2.3. Characterization methods

Material characterization

Adsorption performance

3. Results and discussion

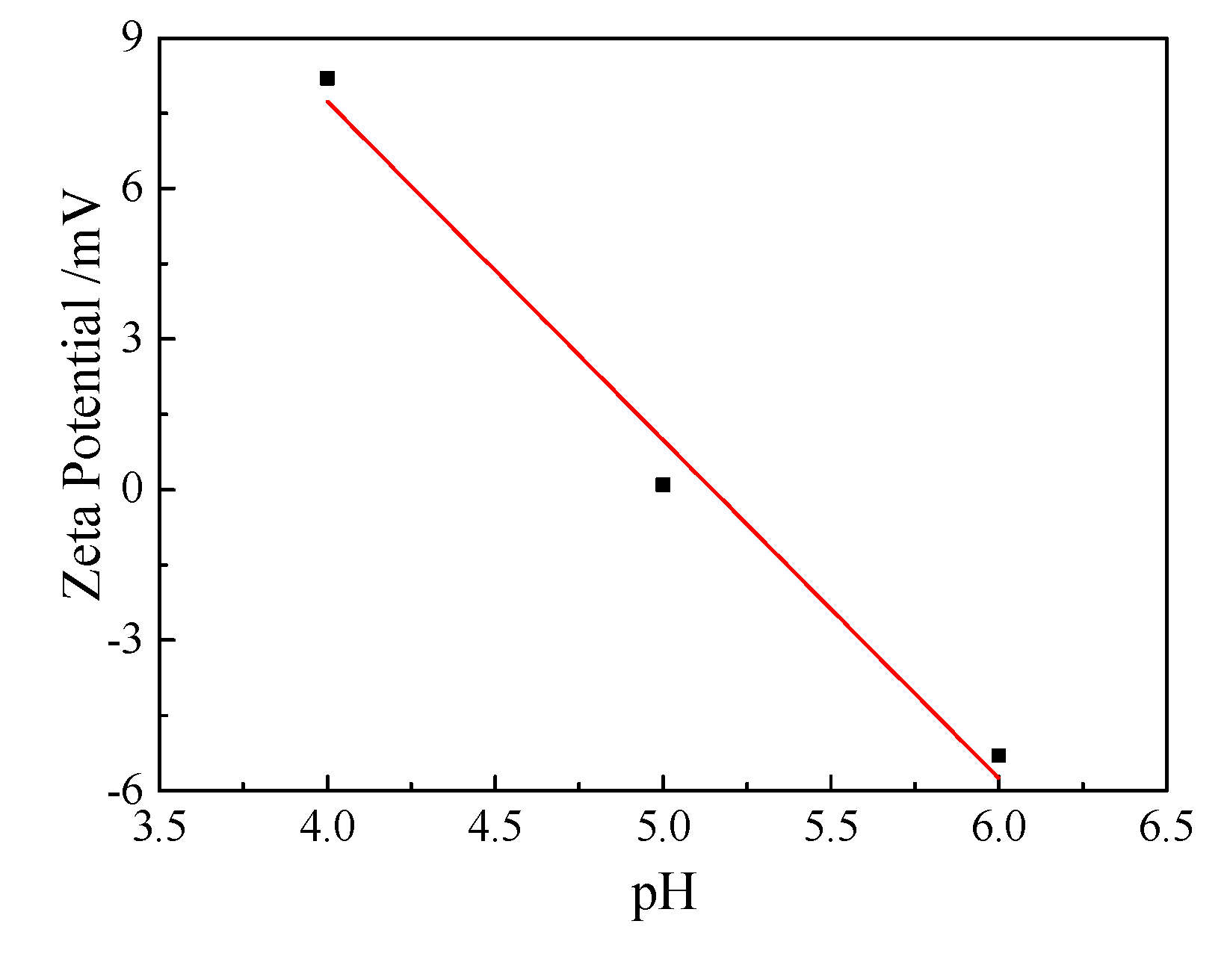

3.1. Factors affecting the adsorption performance of MAS for CR

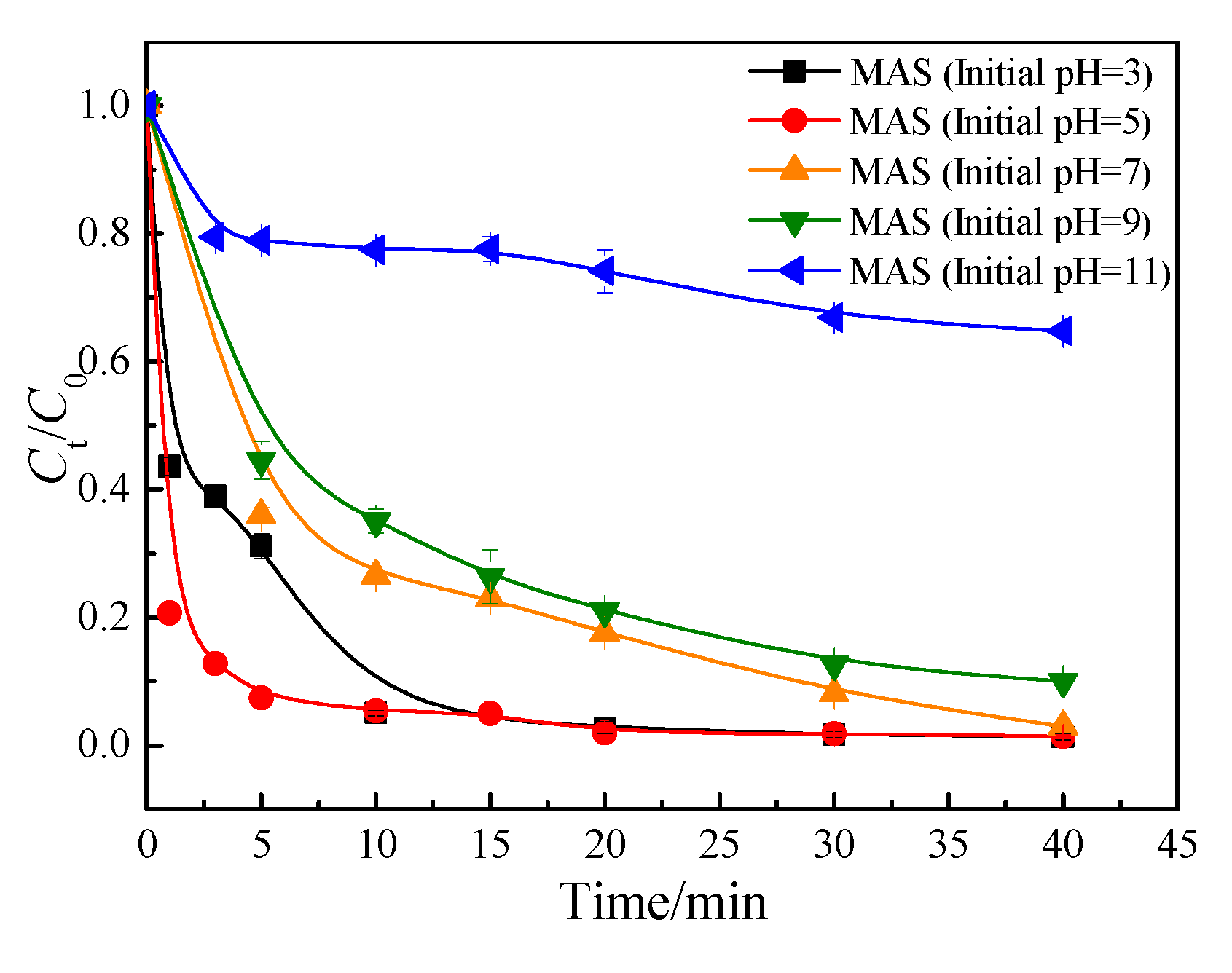

3.1.1. Initial pH

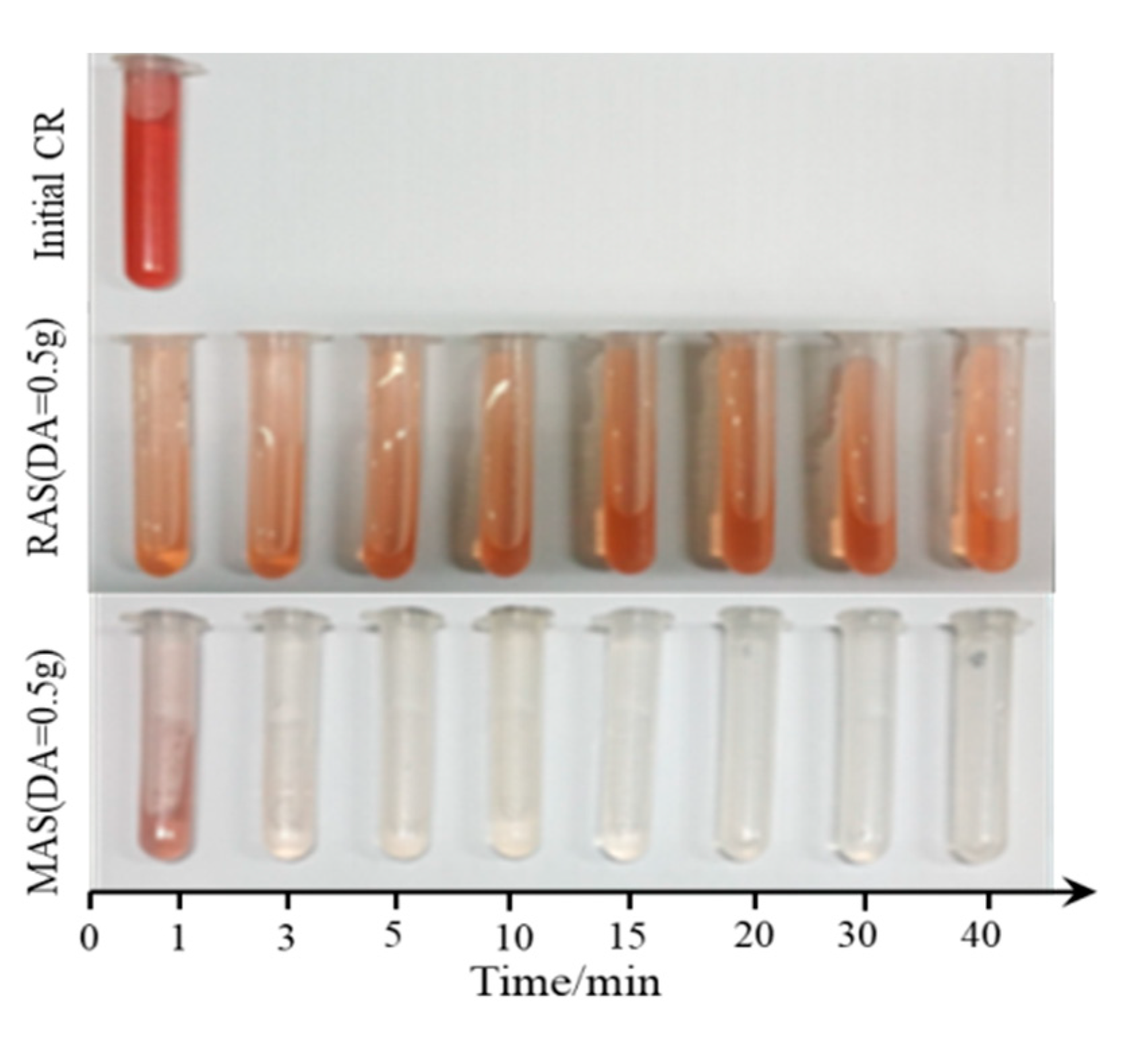

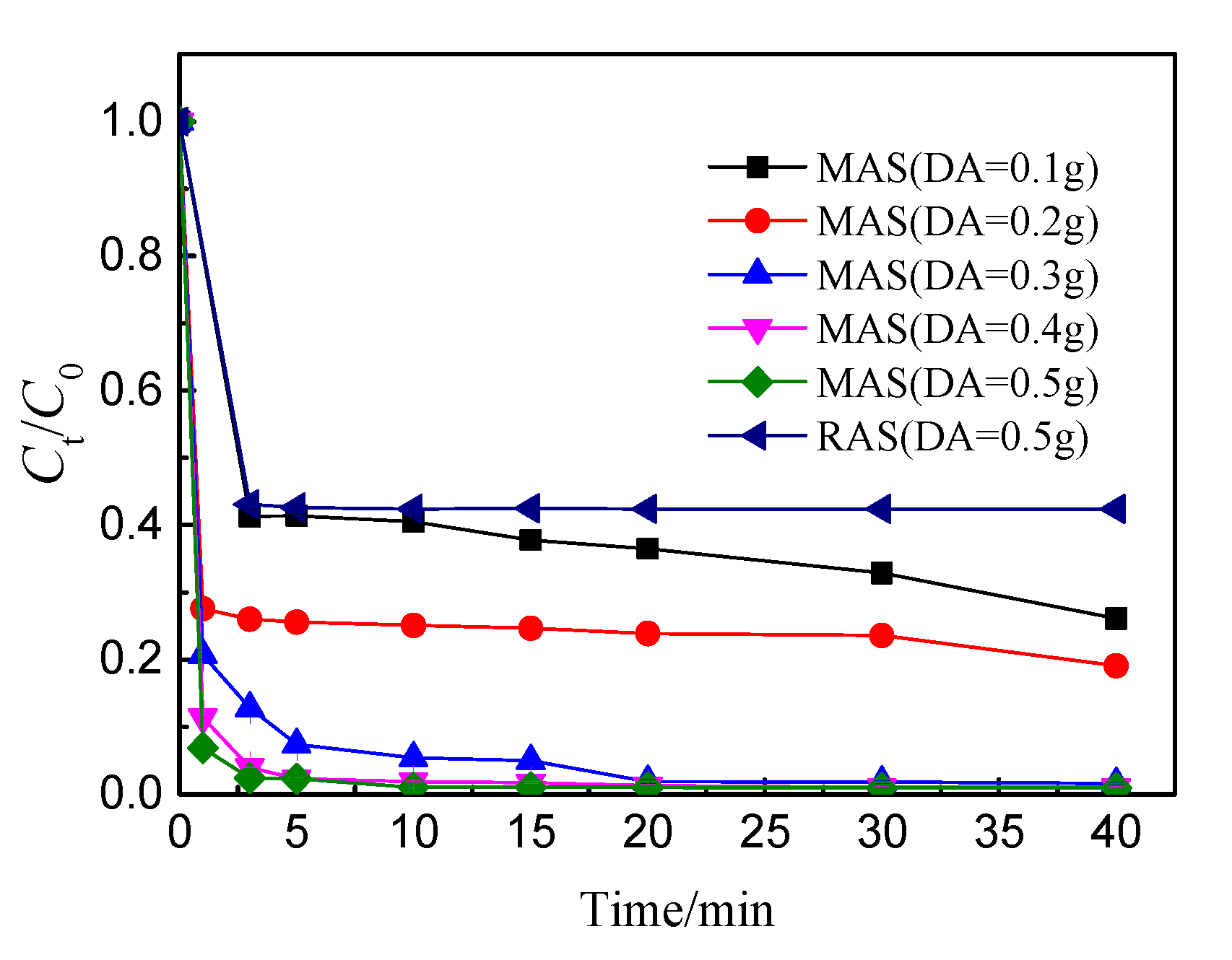

3.1.2. Dosage

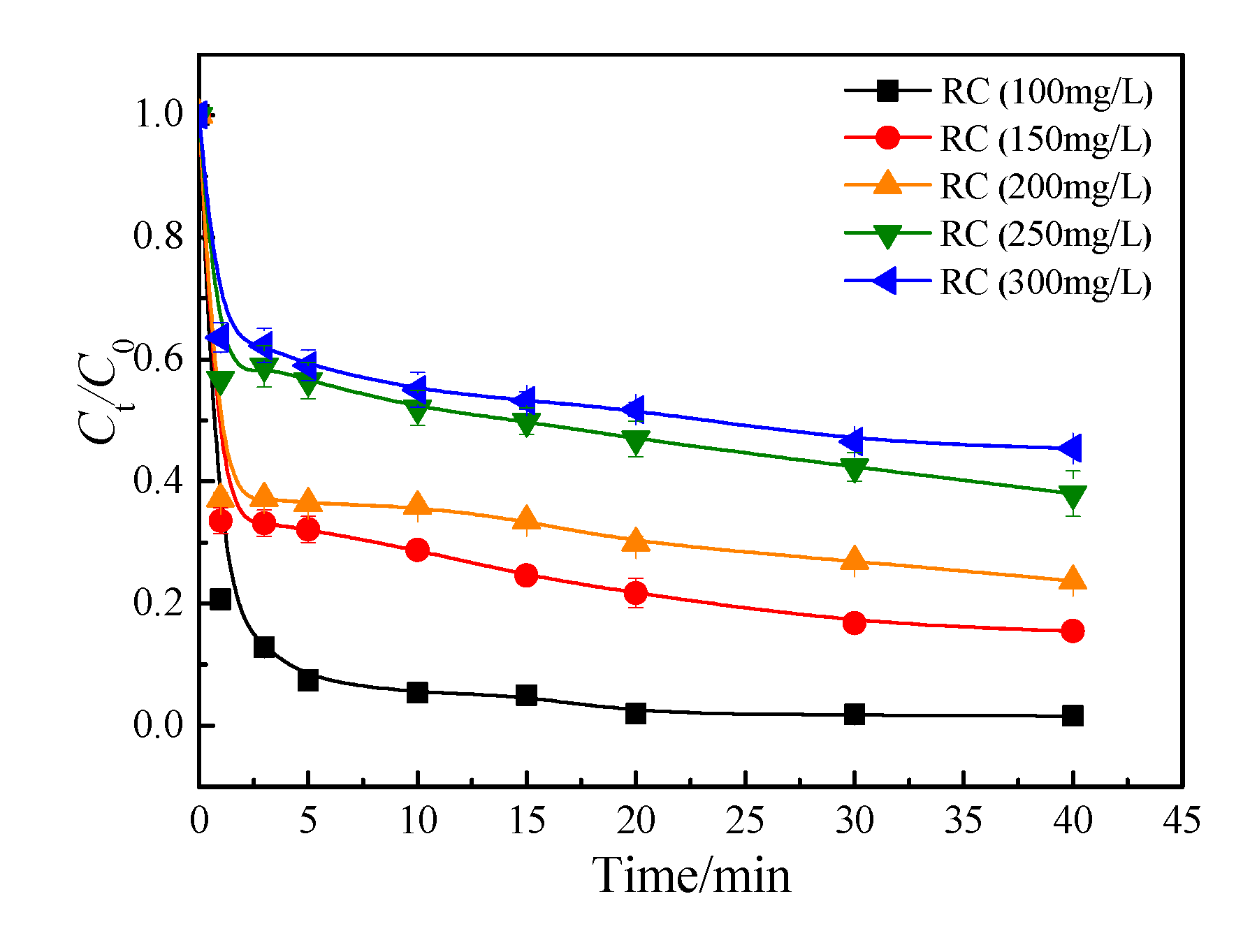

3.1.3. Initial concentration

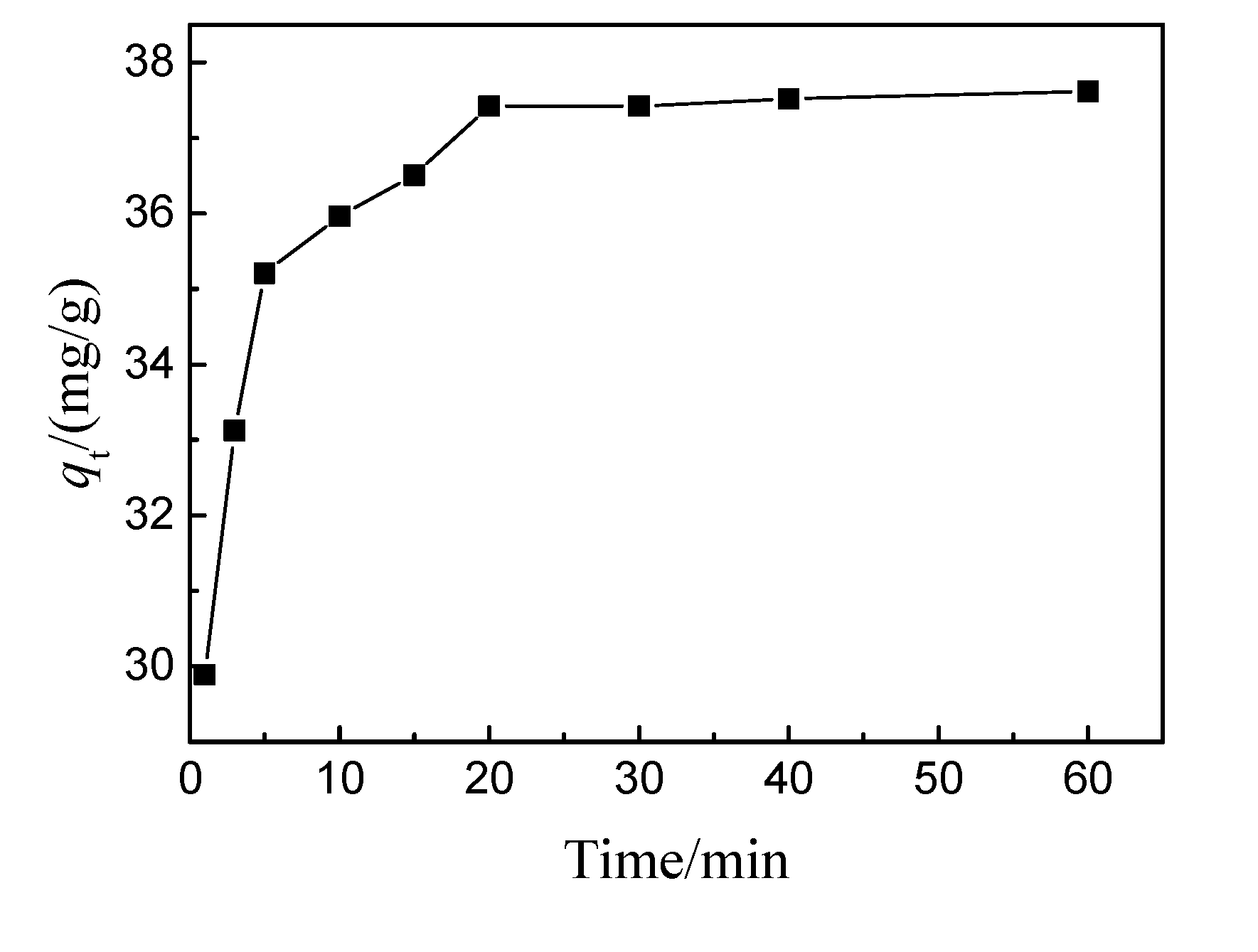

3.1.4. Adsorption kinetics

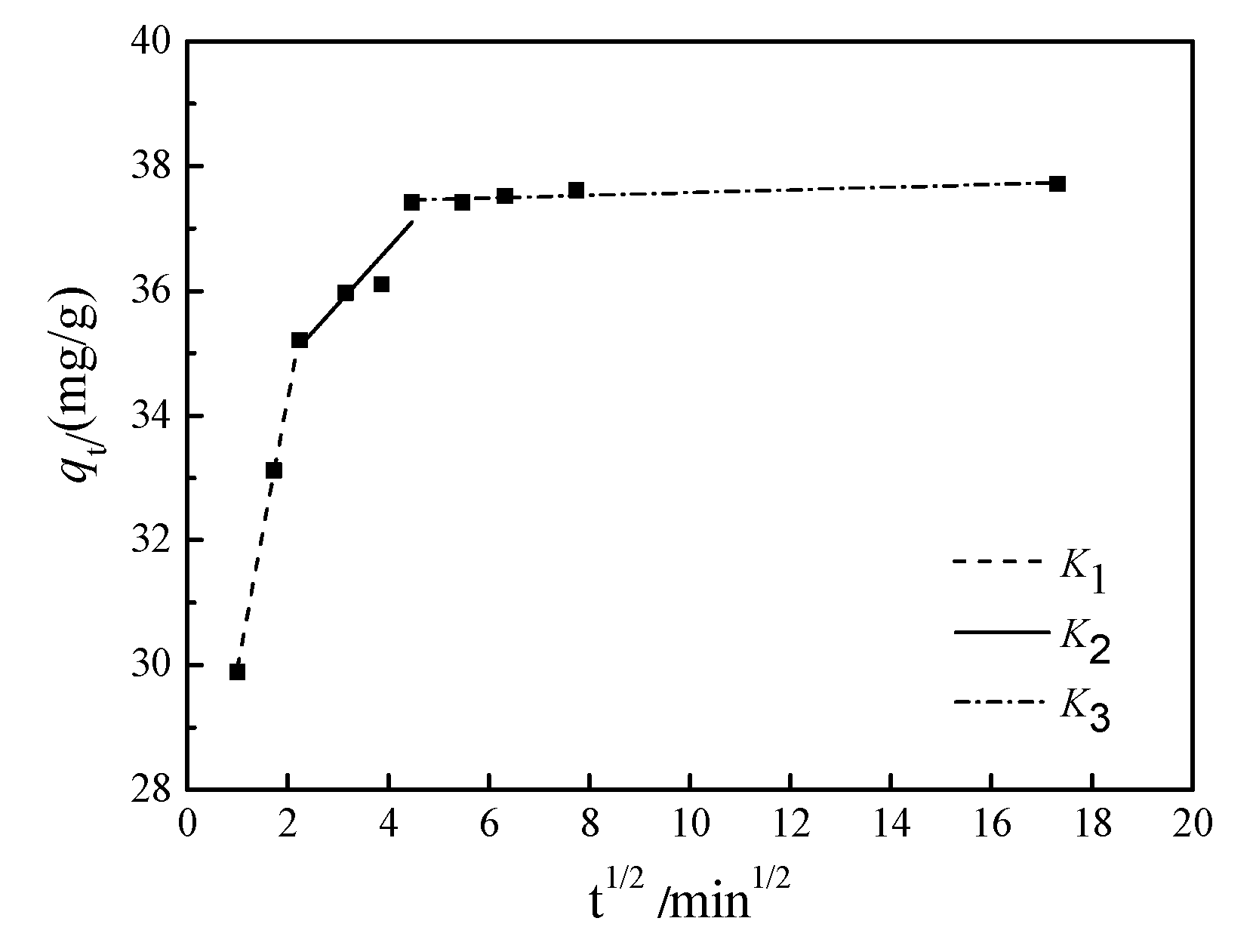

3.1.4. Analysis of internal diffusion mechanism of adsorption

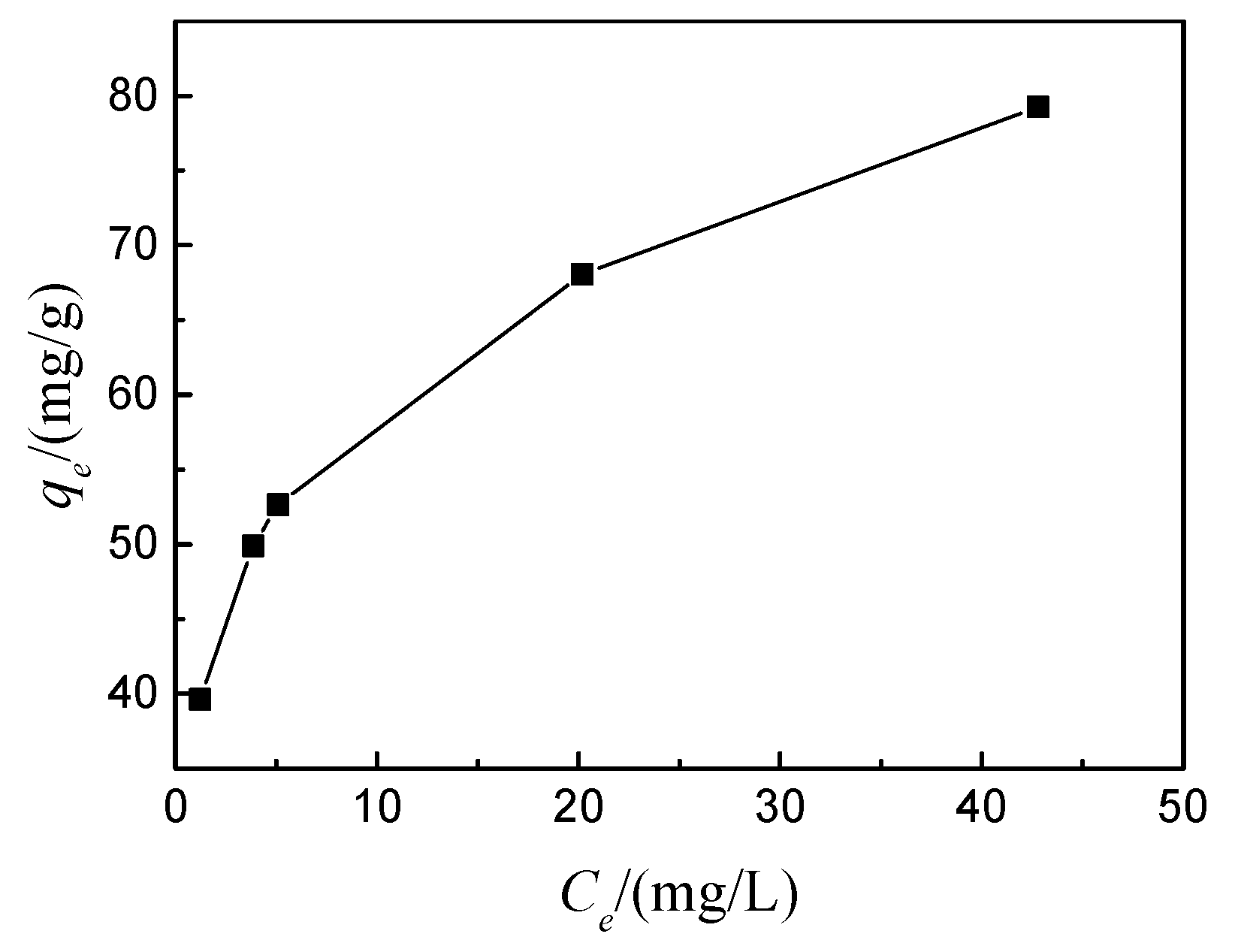

3.1.5. Adsorption isotherm

3.2. MAS characterization analysis

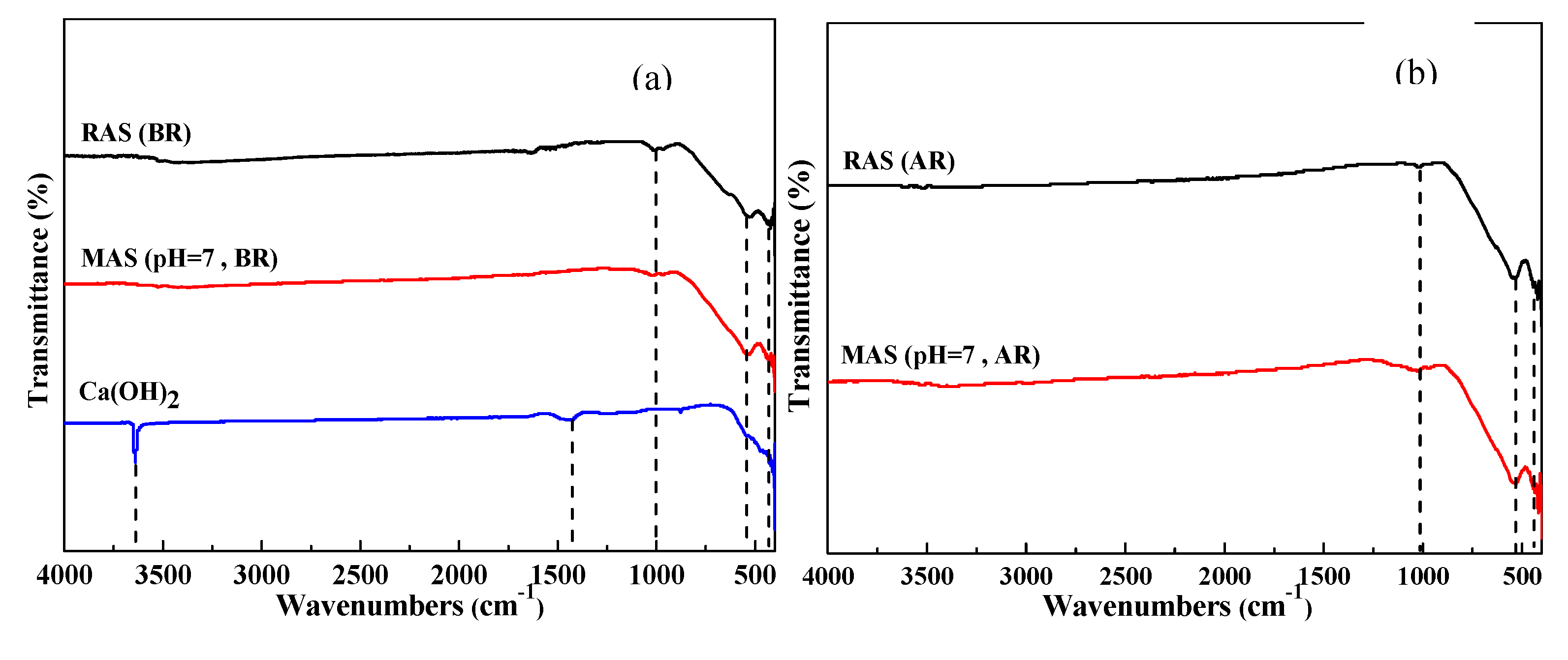

3.2.1. FTIR analysis

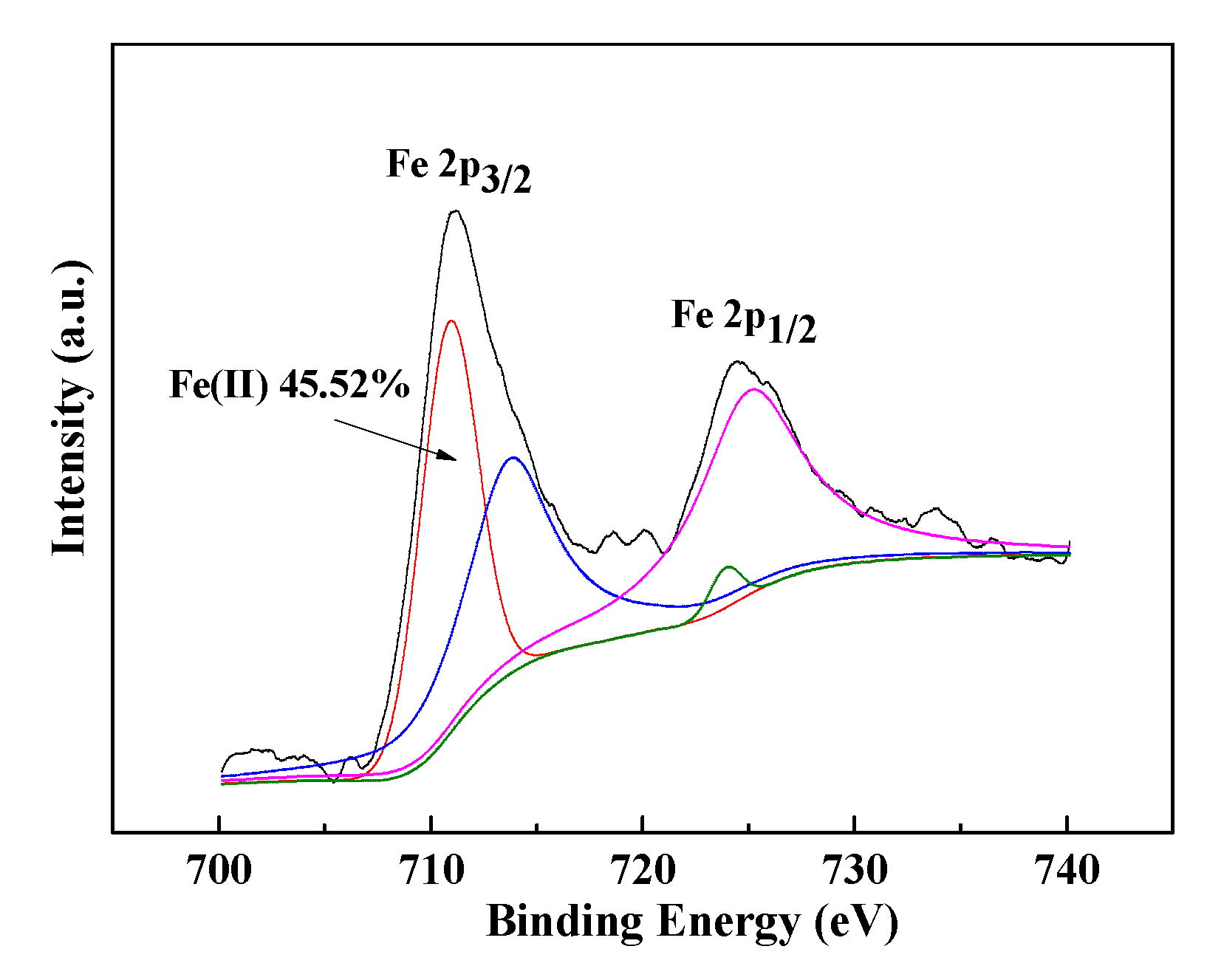

3.2.2. XPS analysis

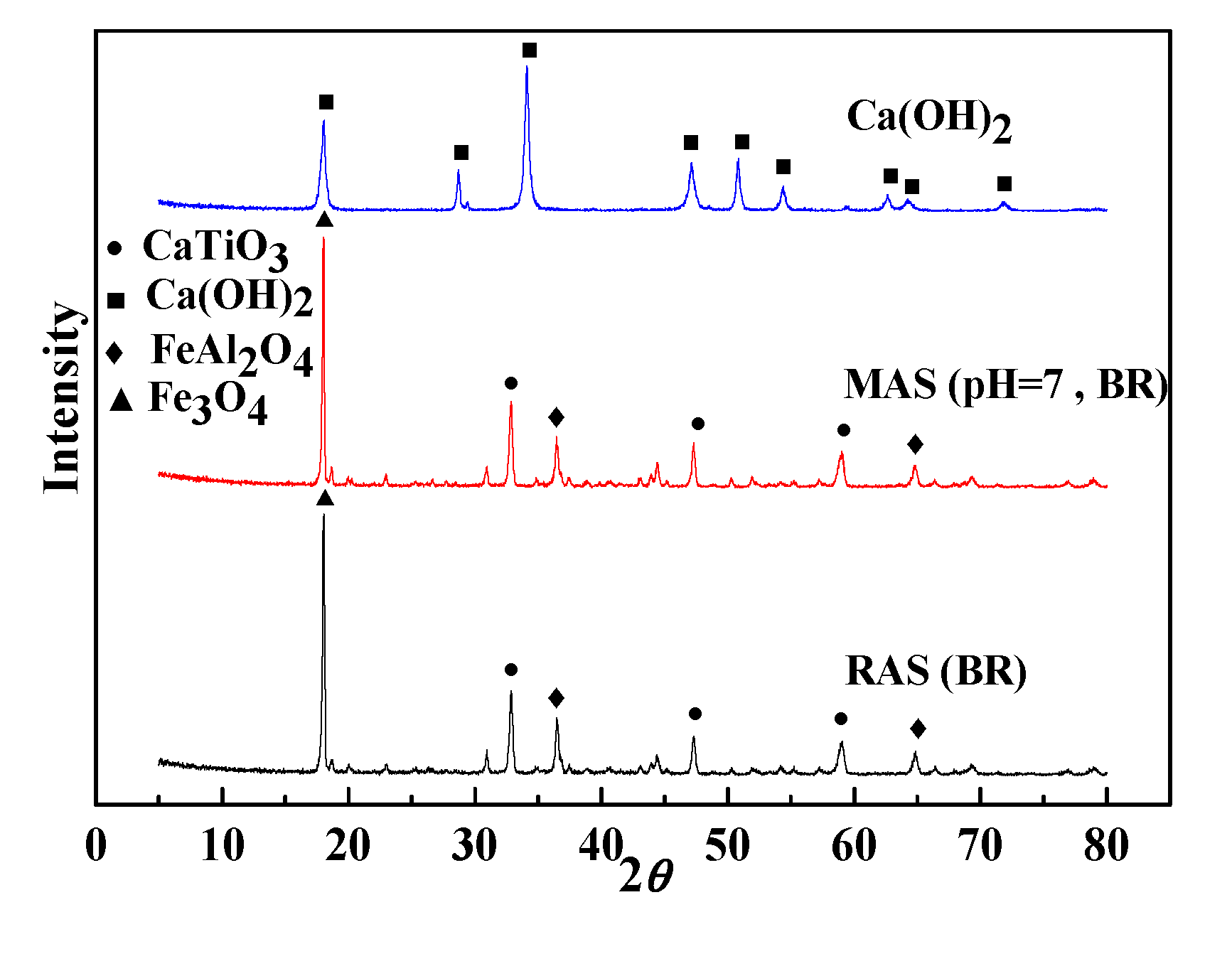

3.2.3. XRD analysis

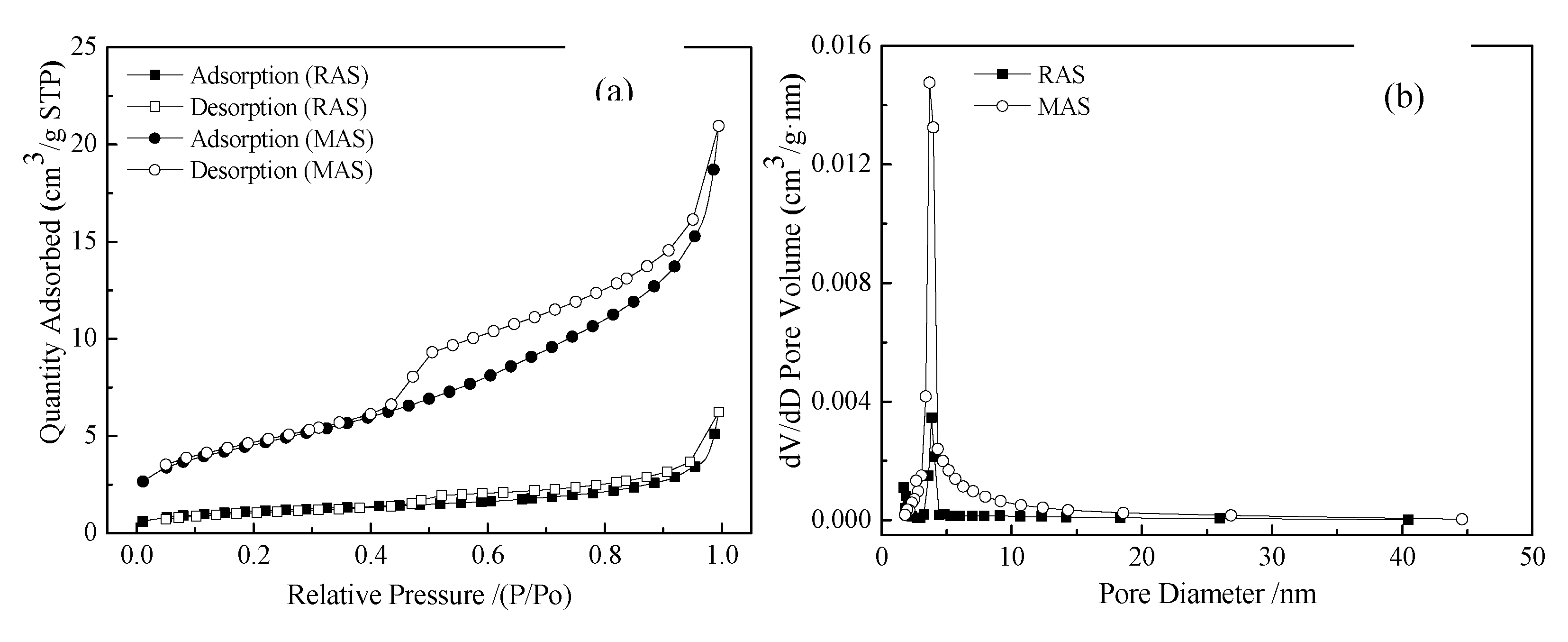

3.2.4. BET analysis

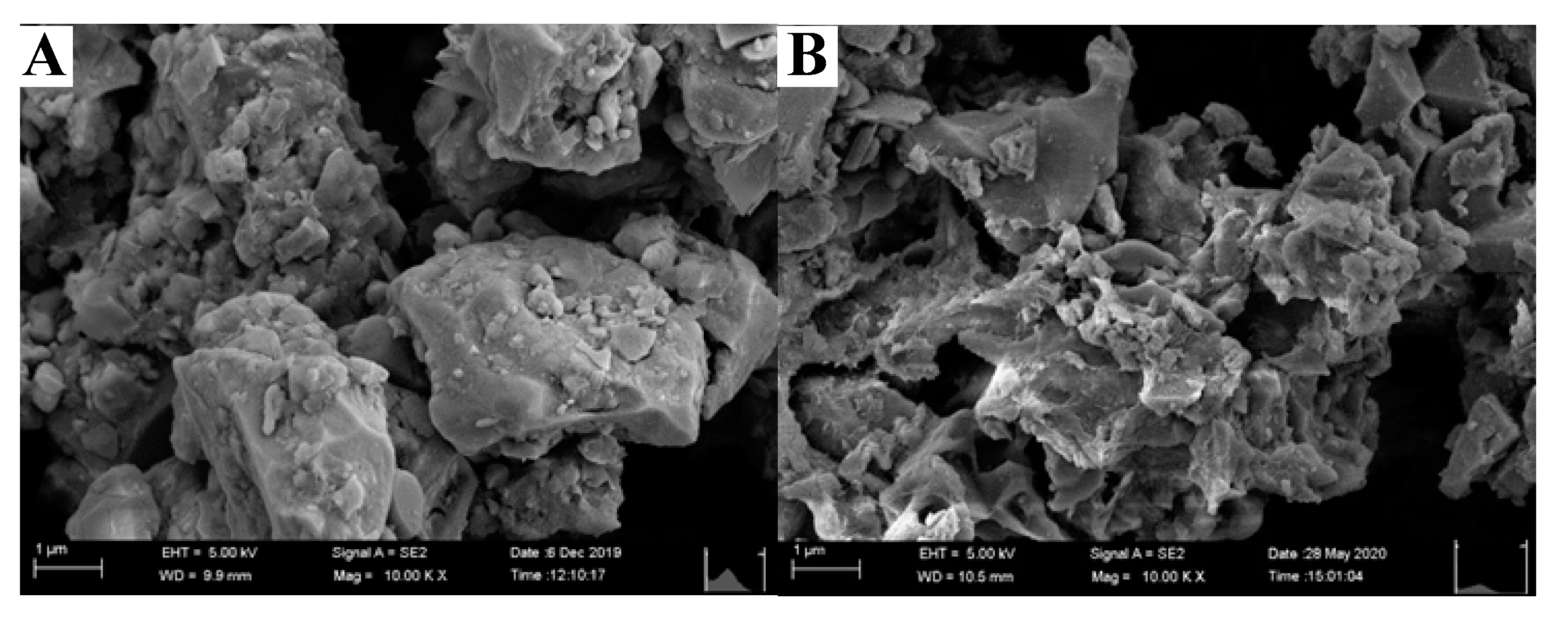

3.2.5. SEM analysis

4. Conclusion

- 1)

- MAS exhibits excellent adsorption behavior for CR. At 25 °C, with an MAS dosage of 0.3g, initial concentration of CR of 100 mg/L, initial pH of 5, and adsorption time of 40 min, the removal rate of CR is 98.41%.

- 2)

- The adsorption behavior of MAS for CR conforms to second-order kinetics, and the adsorption isotherm follows the Freundlich isotherm model. In the Weber-Morris internal diffusion equation, K1>K2>K3, indicating that the adsorption rate is determined by the interaction of membrane diffusion and internal diffusion, and in the membrane diffusion process, the fastest adsorption rate is the fastest.

- 3)

- FTIR and XRD analysis show that the main chemical constituents of MAS are calcium titanium oxide, iron aluminum oxide and iron trioxide with good chemical stability, and XPS analysis confirms that the Fe (II) reaches 45.52%.

- 4)

- After the modification by the hydrothermal treatment of Ca (OH) 2, MAS shows higher porosity and a larger specific surface area. The pore volume and specific surface area of MAS were 3.48 and 3.91 times higher than the value before modification, contributing to its rougher surface and looser pore structure.

Acknowledgments

References

- Shabana, N. , Arjun, A. M., Ankitha, M. & Rsheed, P., A. 2023 Nb2CTx@MoS2 composite as a highly efficient catalyst for the degradation of organic dyes. Catalysis Communications. 173: 106566. [CrossRef]

- Shabnam, R. , Miah, M. A. J., Sharafat, M. K., Alam, M. A., Islam, H. M. T. & Ahmad, H. 2019 Cumulative effect of hydrophobic PLMA and surface epoxide groups in composite polymer particles on adsorption behavior of congo red and direct red-75. Arabian Journal of Chemistry. 12(8), 4989-4999. [CrossRef]

- Alsamhary, K. , Al-enazi, N. M., Alhomaidi, E. & Alwakeel, S. 2022 Spirulina platensis mediated biosynthesis of Cuo Nps and photocatalytic degradation of toxic azo dye Congo red and kinetic studies. Environmental Research. 207, 112172. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. , Deng, B. W., YU, L. Z., Cui, E., Xiang, Z. & Lu, W. 2020 Degradation of azo dyes Congo red by MnBi alloy powders: Performance, kinetics and mechanism. Materials Chemistry and Physics. 251, 123096.

- Sathishkumar, K. , Alsahi, M. S., Sanganyado, E., Devanesan,S., Arulprakash, A. & Rajasekar, A. 2019 Sequential electrochemical oxidation and bio-treatment of the azo dye congo red and textile effluent. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 200, 111655. [CrossRef]

- Munagapati, V. S. , Wen, H., Gollakota, A., Wen, J., Shu, C., Lin, K. A., Tian, Z., Wen, J., Reddy, G. M. & Zyryanov, G. 2022 Magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles loaded papaya (Carica papaya L.) seed powder as an effective and recyclable adsorbent material for the separation of anionic azo dye (Congo Red) from liquid phase: Evaluation of adsorption properties. Journal of Molecular Liquids. 345, 118255. [CrossRef]

- Shen, H. , Liu, B., Shi, Z, Zhao, S., Zhang, J. & Zhang, S. 2021 Reduction for heavy metals in pickling sludge with aluminum nitride in secondary aluminum dross by pyrometallurgy, followed by glass ceramics manufacture. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 418, 126331.

- Shen, H. , Liu, B., Ekberg, C. & Zhang, S. 2021 Harmless disposal and resource utilization for secondary aluminum dross: A review. Science of The Total Environment. 760, 143968. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. , Shen, X., Shao, H., Ning, L., Shi, Y., Han, Q.,Chen, J., Liu, Y. & Zhai, Y. 2022 Facile and template-free fabrication of hollow spherical AlOOH and Al2O3 from the waste aluminum residue: Growth mechanism and fast removal of Congo red. Journal of Solid State Chemistry. 316, 123627. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, E. P. , Silva, T. S., Carvalho, C. M., Selvasembian, R., Chaukura, N., Oliveira, L. M. T. M. & Meneghetti, S. P. 2021 Efficient adsorption of dyes by γ-alumina synthesized from aluminum wastes: Kinetics, isotherms, thermodynamics and toxicity assessment. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. 9(5), 106198.

- Wu, Z. , Yuan, X., Zhong, H., Wang, H., Jiang, L.,Zeng, G. Wang, H., Liu, Z. & Li, Y. 2017 Highly efficient adsorption of Congo red in single and binary water with cationic dyes by reduced graphene oxide decorated NH2-MIL-68(Al). Journal of Molecular Liquids. 247, 215-229. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , Yang, L., Qin, Y., Chen, Z., Wang, T., Wei, S. & Wang, C. 2023 Highly effective removal of methylene blue from wastewater by modified hydroxyl groups materials: Adsorption performance and mechanisms. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 656, 130290. [CrossRef]

- Amalina, F. , Abdrazak, A. S., Krishnan, S., Zularisam, A. W. & Nasrullah, M. 2022 A review of eco-sustainable techniques for the removal of Rhodamine B dye utilizing biomass residue adsorbents. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C. 128, 103267. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. , Yang, Y., Qu, G., Ren, Y., Wang, Z., Ning, P., Wu, F. & Chen, X. 2022 Reuse of secondary aluminum ash: Study on removal of fluoride from industrial wastewater by mesoporous alumina modified with citric acid. Environmental Technology & Innovation. 28, 102868. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q. , Moggridge, G. D., D’agostino, C. 2016 Adsorption of pyridine from aqueous solutions by polymeric adsorbents MN 200 and MN 500. Part 2: Kinetics and diffusion analysis. Chemical Engineering Journal. 306, 1223-1233.

- Guo, X. , Wang, J. 2019 Comparison of linearization methods for modeling the Langmuir adsorption isotherm. Journal of Molecular Liquids. 296, 111850. [CrossRef]

- Ezzati, R. 2020 Derivation of Pseudo-First-Order, Pseudo-Second-Order and Modified Pseudo-First-Order rate equations from Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms for adsorption. Chemical Engineering Journal. 392, 123705. [CrossRef]

- Azha S., F. , Sellaoui, L., Engku Yunus, E. H., Yee, C. J., Bonilla-Petriciolet, A.,Ben, L. A. & Ismail, S. 2019 Iron-modified composite adsorbent coating for azo dye removal and its regeneration by photo-Fenton process: Synthesis, characterization and adsorption mechanism interpretation. Chemical Engineering Journal. 361, 31-40.

- Wang, L. , Yu, Y., Yao, W. 2017 Preparation of nanocrystalline Fe3O4 and study on their adsorption performance for Congo red. Inorganic Chemicals Industry. 49(4), 37-40.

| Adsorbent | qe/(mg·g-1) | Lagergren first-order dynamics | Secondary dynamics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k1/(L·min-1) | qe.c/(mg·g-1) | R2 | k2/(g·mg-1·min-1) | qe.c/(mg·g-1) | R2 | |||

| MAS | 37.713 | 0.0608 | 22.342 | 0.788 | 0.0611 | 37.893 | 0.999 | |

| Weber-Morris internal diffusion model parameters | K1/mg‧g-1‧min-0.5 | R2 | K2/mg‧g-1‧min-0.5 | R2 | K3/mg‧g-1‧min-0.5 | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitting value | 4.315 | 1.00 | 0.893 | 0.808 | 0.022 | 0.725 |

| Adsorbent | Langmuir isotherm parameters | Freundlich isotherm parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q0/mg‧g-1 | b/L‧mg-1 | R2 | K/L‧mg-1 | n | R2 | |

| MAS | 10.41 | 60.04 | 0.874 | 38.24 | 5.16 | 0.999 |

| Material | Specific surface area m2;‧g-1 |

Pore size nm |

Pore volume cm3;‧g-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAS | 4.1820 | 10.1113 | 0.009529 |

| MAS | 16.3308 | 7.0081 | 0.033162 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).