Submitted:

30 June 2023

Posted:

03 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

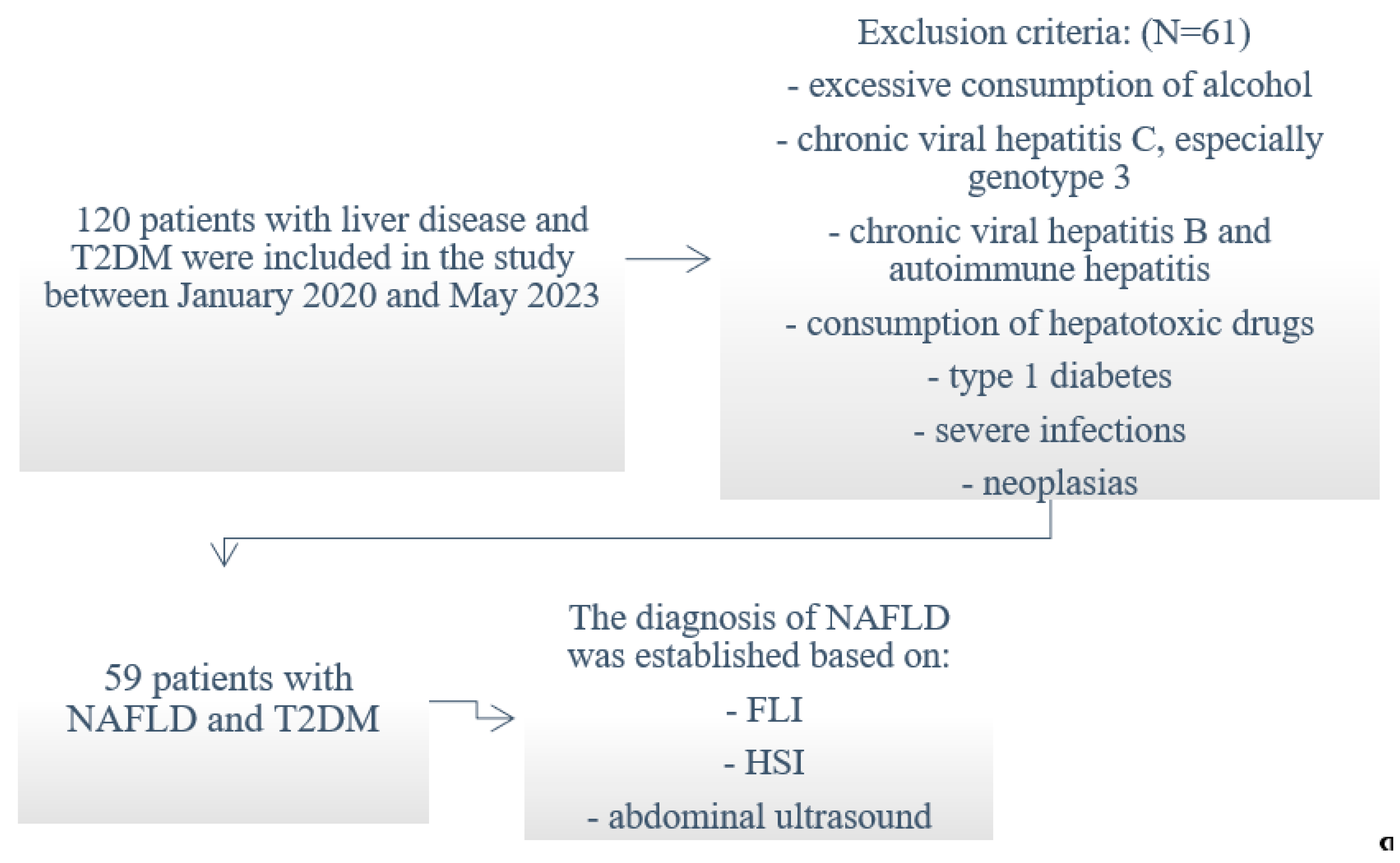

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of patients

2.2. Clinical parameters

2.4. Statistical analysis

2.5. Ethical considerations

3. Results

3.1. Study composition

3.2. The biochemical study

3.3. The hematological study

3.5. Study of inflammatory parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kosmalski, M.; Ziółkowska, S.; Czarny, P.; Szemraj, J.; Pietras, T. The Coexistence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiers, J.; Brindley, J.H. ; Li W; Alazawi Q. What’s new in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? Frontline Gastroenterology 2022, 13, e102–e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, C.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arias-Loste, M.T.; et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States for the period 2016-2030. J Hepatol 2018, 69, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalasani, N.; Younossi, Z.; Lavine, J.E. ; Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, Harrison SA, Brunt EM, Sanyal AJ. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases . Hepatology 2017, 67, 328–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Wong, R.; Fraysse, J.; Shreay, S.; Li, S.; Harrison, S.; Gordon, S.C. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease progression rates to cirrhosis and progression of cirrhosis to decompensation and mortality: a real-world analysis of Medicare data. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020, 51, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.T.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, C.; Corey, K.E.; Chung, R. T; Loomba R; Benjamin EJ. Hepatic Fibrosis Associates With Multiple Cardiometabolic Disease Risk Factors: The Framingham Heart Study. Hepatology 2021, 73, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, G.P.; De La Cerda, I.; Pan, J.; Fallon, M.B. ; Beretta L; Loomba R; Lee M; McCormick J.B; Fisher-Hoch S.P. Elevated Glycated Hemoglobin Is Associated With Liver Fibrosis, as Assessed by Elastography, in a Population-Based Study of Mexican Americans. Hepatology Communications 2020, 4, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caussy, C.; Aubin, A.; Loomba, R. The Relationship Between Type 2 Diabetes, NAFLD, and Cardiovascular Risk. Current Diabetes Reports 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarghamravanbakhsh, P.; Frenkel, M.; Poretsky, L. Metabolic causes and consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism Open 2021, 12, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caussy, C.; Soni, M.; Cui, J.; Bettencourt, R.; Schork, N.; Chen, C.H; Ikhwan, M.A; Bassirian, S.; Cepin, S.; et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with cirrhosis increases the familial risk for advanced fibrosis. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2017, 127, 2697–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheodoridi, M.; Cholongitas, E. Diagnosis of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): Current Concepts 2019, 24, 4574–4586. [CrossRef]

- Manousou, P.; Kalambokis, G.; Grillo, F.; Watkins, J.; Xirouchakis, E.; Pleguezuelo, M.; Leandro, G.; Arvaniti, V.; Germani, G.; Patch, D.; Calvaruso, V.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Dhillon, A.P.; Burroughs, A.K. Serum ferritin is a discriminant marker for both fibrosis and inflammation in histologically proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Liver Int 2011, 31, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedogni, G.; Miglioli, L.; Masutti, F.; et al. Incidence and natural course of fatty liver in the general population: the Dionysos study. Hepatology 2007, 46, 1387–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieckowska, A.; McCullough, A.J.; Feldstein, A.E. Noninvasive diagnosis and monitoring of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: present and future. Hepatology 2007, 46, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslam, M.; George, J. Reply to: correspondence regarding “A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement.”. Journal of Hepatology 2020, 73, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, F.; Shubrook, J.H.; Adams, L.A.; Pfotenhauer, K.; Wai-Sun Wong, V.; Wright, E.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Harrison, S.A.; Loomba, R.; Mantzoros, C.S.; et al. Clinical Care Pathway for the Risk Stratification and Management of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1657–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinou, E.; Pericleous, M.; Stefanova, I.; Kaur, V.; Angelidi, A.M. Diagnostic Modalities of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: From Biochemical Biomarkers to Multi-Omics Non-Invasive Approaches. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, S.; Cabrera, D.; Arrese, M.; Feldstein, A.E. Triggering and resolution of inflammation in NASH. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 15, 349–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanovic Alempijevic, T.; Stojkovic Lalosevic, M.; Dumic, I.; Jocic, N.; Pavlovic Markovic, A.; Dragasevic, S.; Jovicic, I.; Lukic, S.; Popovic, D.; Milosavljevic, T. Diagnostic Accuracy of Platelet Count and Platelet Indices in Noninvasive Assessment of Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Patients. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2017, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.F.; Chien, L.W. Predictive Role of Neutrophil-Percentage-to-Albumin Ratio (NPAR) in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Advanced Liver Fibrosis in Nondiabetic US Adults: Evidence from NHANES 2017–2018. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Huang, D.; Ma, H.; Qian, C.; You, H. ; Bu L; Qu S. High-Sensitive CRP Correlates With the Severity of Liver Steatosis and Fibrosis in Obese Patients With Metabolic Dysfunction Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Z.; Cai, J.J.; Yu, Y.; She, Z.G.; Li, H. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: An Update on the Diagnosis. Gene Expr 2019, 19, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis - 2021 update. J Hepatol 2021, 75, 659–689. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.H.; Cai, J.J.; She, Z.G.; Li, H.L. Noninvasive evaluation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Current evidence and practice. World J Gastroenterol 2019, 25, 1307–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatty Liver Index (FLI) MD App Avaiable on https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/10001/fatty-liver-index#nextsteps.

- Bedogni, G.; Bellentani, S.; Miglioli, L.; Masutti, F.; Passalacqua, M.; Castiglione, A.; Tiribelli, C. The Fatty Liver Index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterology 2006, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepatic Steatosis Index (HSI) MD App Avaiable on https://www.mdapp.co/hepatic-steatosis-index-hsicalculator- 357 (Assessed on 23.06.2023).

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, C.H.; Yang, J.I.; Kim, W.; Kim, Y.J.; Yoon, J.H.; Cho, S.H.; Sung, M.W.; Lee, H.S. Hepatic steatosis index: a simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis 2010, 42, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, A.; Pereira, S.E.; Saboya, C.J.; Ramalho, A. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Relationship with Metabolic Syndrome in Class III Obesity Individuals. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 839253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.Y.; Fang, T.J.; Hung, W.W.; Tsai, H.J.; Tsai, Y.C. The Determinants of Liver Fibrosis in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomonaco, R.; Bril, F.; Portillo-Sanchez, P.; Ortiz-Lopez, C.; Orsak, B.; Biernacki, D.; Lo, M.; Suman, A.; Weber, M.; Cusi, K. Metabolic Impact of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Obese Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, N.; Wang, B.; Lu, Y. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes: an observational and Mendelian randomization study. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardo, A.; Ballestri, S.; Guaraldi, G.; Nascimbeni, F.; Romagnoli, D.; Zona, S.; Targher, G. Fatty liver is associated with an increased risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease - Evidence from three different disease models: NAFLD, HCV and HIV. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 9674–9693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.S.; Drocas, A.I.; Osman, A.; Firu, D.M.; Padureanu, V.; Marginean, C.M.; Pirvu, D.C.; Mitrut, R.; Margaritescu, D.N.; Radu, A.; et al. The Extent of Insulin Resistance in Patients That Cleared Viral Hepatitis C Infection and the Role of Pre-Existent Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis. Reports 2022, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazick, J.; Donithan, M.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Kleiner, D.; Brunt, E.M. ; Wilson L,; Doo E.; Lavine J.; Tonascia J.; Loomba R. Clinical Model for NASH and Advanced Fibrosis in Adult Patients With Diabetes and NAFLD: Guidelines for Referral in NAFLD. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Sng, W.K.; Hui-Min Quah, J.; Liu, J.; Chong, B.Y.; et al. Clinical spectrum of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with diabetes mellitus. PloS One 2020, 15, e0236977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julián, MT.; Pera, G.; Soldevila, B.; Caballería, L.; Julve, J.; Puig-Jové, C.; Morillas, R.; Torán, P.; Expósito, C.; Puig-Domingo, M.; Castelblanco, E.; Franch-Nadal, J.; Cusi, K.; Mauricio, D.; Alonso, N. Atherogenic dyslipidemia, but not hyperglycemia, is an independent factor associated with liver fibrosis in subjects with type 2 diabetes and NAFLD: a population-based study. European Journal of Endocrinology 2021, 184, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.; Lang, S.; Goeser, T.; Demir, M.; Steffen, H.M.; Kasper, F. Management of Dyslipidemia in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Current Atherosclerosis Reports 2022, 24, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashanth, M.; Ganesh, H.K.; Vimal, M.V.; John, M.; Bandgar, T.; et al. Prevalence of Nonalcoholic fatty Liver Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Japi 2009, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman A.N; Fadem, S.Z. Reassessment of albumin as a nutritional marker in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2010, 21, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofrad, P.; Contos, M.J.; Haque, M.; et al. Clinical and histologic spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with normal ALT values. Hepatolog 2003, 37, 1286–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Bhattarai, B.; Kafle, P.; Khalid, M.; Jonnadula, S.K.; Lamicchane, J.; Kanth, R.; Gayam, V. Elevated Liver Enzymes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cureus 2018, 10, e3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, HE. Elevated Liver Function Tests in Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Diabetes 2005, 23, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N.; Bhatt, N.P.; Neopane, P.; Dahal, S.; Regmi, P.; Khanal, M.; Shrestha, R. Hepatic involvement with elevated liver enzymes in Nepalese subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Biochem Res Rev 2017, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, S.; Paolicchi, A.; Corti, A.; Maellaro, E.; Pompella, A. Prooxidant reactions promoted by soluble and cell-bound g-glutamyltransferase activity. Methods Enzymol 2005, 401, 484–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunutsor, S.K. Gamma-glutamyltransferase-friend or foe within? Liver Int 2016, 36, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.W.; Huang, M.S.; Shyu, Y.C.; Chien, R.N. Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase elevation is associated with metabolic syndrome, hepatic steatosis, and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A community-based cross-sectional study. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2021, 37, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.H.; Lee, B.; Choi, D.H.; Jung, S.H.; Kim, B.Y.; Kim, C.H.; Kang, S.K.; Mok, J.O. Association of grade of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and glycated albumin to glycated hemoglobin ratio in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2017, 125, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, N.K.; Kahraman, C.; Kocak, F.E.; Cosgun, S.; Sanal, B.; Korkmaz, M.; Bayham, Z.; Zeren, S. Predictive value of neutrophiltolymphocyte ratio in the severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among type 2 diabetes patients. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2016, 79, 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Kapici, O.B.; Abus, S.; Ayhan, S.; Karaagac, M.; Sirik, M. Investigation of hemogram and biochemistry parameters in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Medicine Science | International Medical Journal 2023, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; He, X.; Hao, J.; Shen, A.; Zhao, H.; Chen, S.; Ren, L. Factors Associated with Liver Fibrosis in Chinese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. International Journal of General Medicine 2023, 16, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanovic, A.T.; Stojkovic, L.M.; Dumic, I.; Jocic, N.; Pavlovic Markovic, A.; Dragasevic, S.; Jovicic, I.; Lukic, S.; Popovic, D.; Milosavljevic, T. Diagnostic Accuracy of Platelet Count and Platelet Indices in Noninvasive Assessment of Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Patients. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2017, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingle, S.J.; Ma, G.R.S.; Goodfellow, M.; Moir, J.A.; White, S.A. NARCA: A novel prognostic scoring system using neutrophil albumin ratio and Ca19-9 to predict overall survival in palliative pancreatic cancer. J. Surg. Oncol 2018, 118, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, D.; Cheng, B.; Ying, B.; Gong, Y. The Neutrophil Percentage-to-Albumin Ratio Is Associated with All-Cause Mortality in Critically Ill Patients with Acute Kidney Injury. Biomed Res Int 2020, 18, 5687672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Li, D.; Cheng, B.; Ying, B.; Wang, B. Increased neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio is associated with all-cause mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Epidemiol Infect 2020, 148, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjot, T.; Moolla, A.; Cobbold, J.F.; Hodson, L.; Tomlinson, J.W. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Adults: Current Concepts in Etiology, Outcomes, and Management. Endocr. Rev 2020, 41, 66–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosen, SH.; Demir, M.; Kunstein, A.; Jördens, M.; Qvarskhava, N.; Luedde, M.; Luedde, T.; Roderburg, C.; Kostev, K. Variables associated with increased incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2021, 9, e002243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okdahl, T.; Wegeberg, AM.; Pociot, F.; Brock, B.; Størling, J.; Brock, C. Low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes: A crosssectional study from a Danish diabetes outpatient clinic. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e062188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, G.; Ding, J.; Shen, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y. Association between serum ferritin and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among middle-aged and elderly Chinese with normal weight. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2019, 28, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Apekey, T.A.; Walley, J.; Kain, K. Ferritin levels and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective evidence. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews 2013, 29, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, R.F.; El Bendary, A.S.; Ezzat, S.E.; Mohamed, W.S. Serum ferritin level, microalbuminuria and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2diabetic patients. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome 2019, 13, 2226–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.X.; Pan, B.J.; Zhao, P.P.; Wang, L.T.; Liu, J.F.; Fu, S.B. Serum ferritin is crrelated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in middle-aged and older patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr Connect 2021, 29, 10, 1560–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, R.; Pisano, G.; Fargion, S. Role of serum uric acid and ferritin in the development and progression of NAFLD. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachinidis, A.; Doumas, M.; Imprialos, K.; Stavropoulos, K.; Katsimardou, A.; Athyros, V.G. Dysmetabolic iron overload in metabolic syndrome. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2020, 26, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Choi, J.S.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, W.H.; Park, S.I.; Song, J. Effect of excess iron on oxidative stress and gluconeogenesis through hepcidin during mitochondrial dysfunction. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2015, 26, 1414–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Kim, B.I.; Yun, J.W.; Kim, J.W.; Park, D.I.; Cho, Y.K.; Sung, I.K.; Park, C.Y.; Sohn, CI.; Jeon, W.K.; et al. Insulin resistance and C-reactive protein as independent risk factors for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in non-obese Asian men. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2004, 19, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.; Hui, A.Y.; Tsang, S.W.; Chan, J.L.; Tse, A.M.; Chan, K.F.; So, W.Y.; Cheng, A.Y.; Ng, W.F.; Wong, G.L.; et al. Metabolic and adipokine profile of Chinese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2006, 4, 1154–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Cardellini, M.; Hoyles, L.; Latorre, J.; Davato, F.; Moreno-Navarrete, J.M.; Arnoriaga-Rodríguez, M.; Serino, M.; Abbott, J.; Barton R., H.; et al. Iron status influences non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obesity through the gut microbiome. Microbiome 20219, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haukeland, J.W.; Damås, J.K.; Konopski, Z.; Løberg, E.M.; Haaland, T.; Goverud, I.; Torjesen, P.A.; Birkeland, K.; Bjøro, K. ; Aukrust P: Systemic inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is characterized by elevated levels of CCL2. J Hepatol 2006, 44, 1167–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, M.; Mawatari, H.; Fujita, K.; Iida, H.; Yonemitsu, K.; Kato, S.; Takahashi, H.; Kirikoshi, H.; Inamori, M.; Nozaki, Y.; Abe, Y.; Kubota, K.; Saito, S.; Iwasaki, T.; Terauchi, Y.; Togo, S.; Maeyama, S. ; Nakajima A: High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is an independent clinical feature of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and also of the severity of fibrosis in NASH. J Gastroenterol 2007, 42, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, A.; Arrese, M.; Soza, A.; Morales, A.; Baudrand, R.; Pérez-Ayuso, RM.; González, R.; Alvarez, M.; Hernández, V.; García-Zattera, MJ.; Otarola, F.; Medina, B.; Rigotti, A.; Miquel, JF.; Marshall, G.; Nervi, F. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with obesity, insulin resistance and increased serum levels of C-reactive protein in Hispanics. Liver Int 2009, 29, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, PC.; Shiesh, SC.; Wu, TJ. Serum C-reactive protein as a marker for wellness assessment. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2006, 36, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Oruc, N.; Ozutemiz, O.; Yuce, G.; et al. Serum procalcitonin and CRP levels in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a case control study. BMC Gastroenterol 2009, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndumele, C.E.; Nasir, K.; Conceiçao, R.D.; Carvalho, J.A.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Santos, R.D. Hepatic steatosis, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome are independently and additively associated with increased systemic inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2011 31, 1927-1932. [CrossRef]

- Viallon, A.; Zeni, F.; Pouzet, V.; Lambert, C.; Quenet, S.; Aubert, G.; Guyomarch, S.; Tardy, B.; Bertrand, J.C. Serum and ascitic procalcitonin levels in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: diagnostic value and relationship to pro-inflammatory cytokines. Intensive Care Med 2000, 26, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandona, P.; Nix, D.; Wilson, MF.; Aljada, A.; Love, J.; Assicot, M.; Bohuon, C. Procalcitonin increase after endotoxin injection in normal subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994, 79:1605-1608.

| Parameter | Incidence and Mean Value in Patients with NAFLD and T2DM | Incidence and Mean Value in Patients with HS and T2DM | Incidence and Mean Value in Patients with NASH and T2DM | Statistical Significance p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (number) | 25/59 (42.37%) | 21/44 (47.27%) | 4/15 (26.66%) | 0.07 |

| Men (number) | 34/59 (57.62%) | 23/44 (52.27%) | 11/15 (73.33%) | 0.15 |

| Age (years) | 61.52±10.07 | 62.20±0.70 | 59.53±10.06 | 0.38 |

| The environment of urban origin (number) | 36/59 (61.01%) | 25/44 (56.81%) | 11/15 (73.33%) | 0.26 |

| The rural environment of origin (number) | 23/59 (38.89%) | 19/44 (43.18%) | 4/15 (26.66%) | 0.29 |

| T2DM | 59/59 (100%) | 44/44 (100%) | 15/15 (100%) | - |

| Hypertension | 53/59 (89.83%) | 39/44 (88.63%) | 14/15 (93.33%) | 0.61 |

| Obesity | 54/59 (91.52%) | 41/44 (93.18%) | 13/15 (86.66%) | 0.44 |

| Dyslipidemia | 47/59 (79.66%) | 36/44 (81.81%) | 11/15 (73.33%) | 0.48 |

| MS | 56/59 (94.91%) | 42/44 (95.45%) | 14/15 (93.33 %) | 0.75 |

| FLI | 77.76±22.42 | 74.40±22.62 | 88.93±10.59 | 0.04 ⃰ |

| HSI | 46.58±8,71 | 45.31±7.91 | 50.39±10.17 | 0.05⃰ |

| US-LLL_diameter (cm) | 7.54±1.14 | 7.38±1.83 | 8±1.37 | 0.07 |

| US-RHL_diamater (cm) | 14.3±1.95 | 14.05±2.03 | 15.02±1.48 | 0.09 |

| US-PV_diameter (cm) | 1.084±0.108 | 1.072±00.7 | 1.12±0.104 | 0.15 |

| US-Spleen_diameter (cm) | 10.35±1.09 | 10.21±1 | 10.7±1.22 | 0.09 |

| Parameter | Incidence and mean value in patients with NAFLD and T2DM |

Incidence and mean value in patients with HS and T2DM | Incidence and mean value in patients with NASH and T2DM |

Statistical significance p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

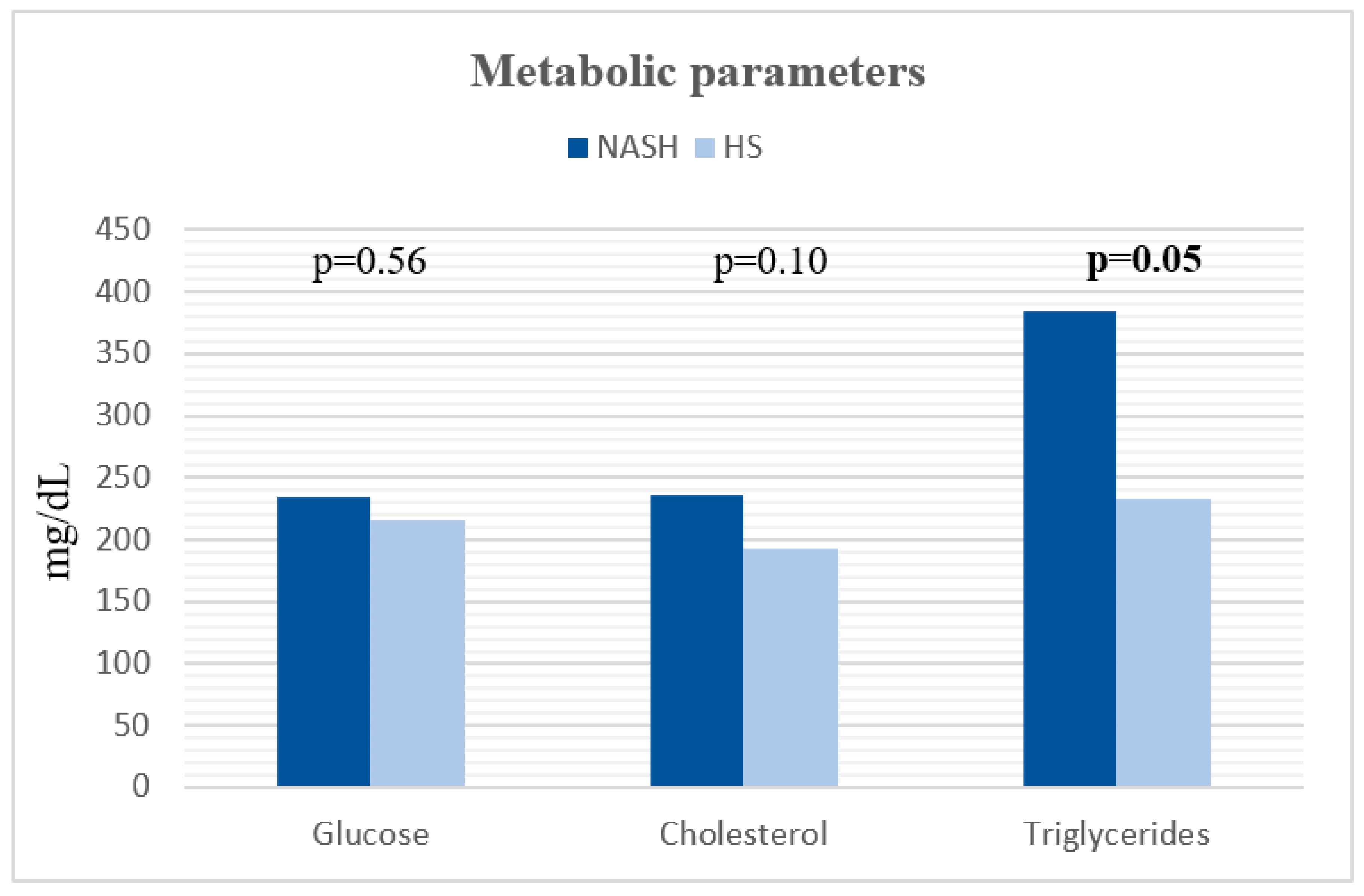

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 220.74±103.61 | 216.11±107.59 | 234.33±89.56 | 0.56 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.34±1.97 | 8.26±2.74 | 8.57±1.67 | 0.60 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 204.40±88.62 | 193.59±16.26 | 235.73±145.13 | 0.10 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 271.30±290.061 | 232.79±14.14 | 384.26±450.90 | 0.05 ⃰ |

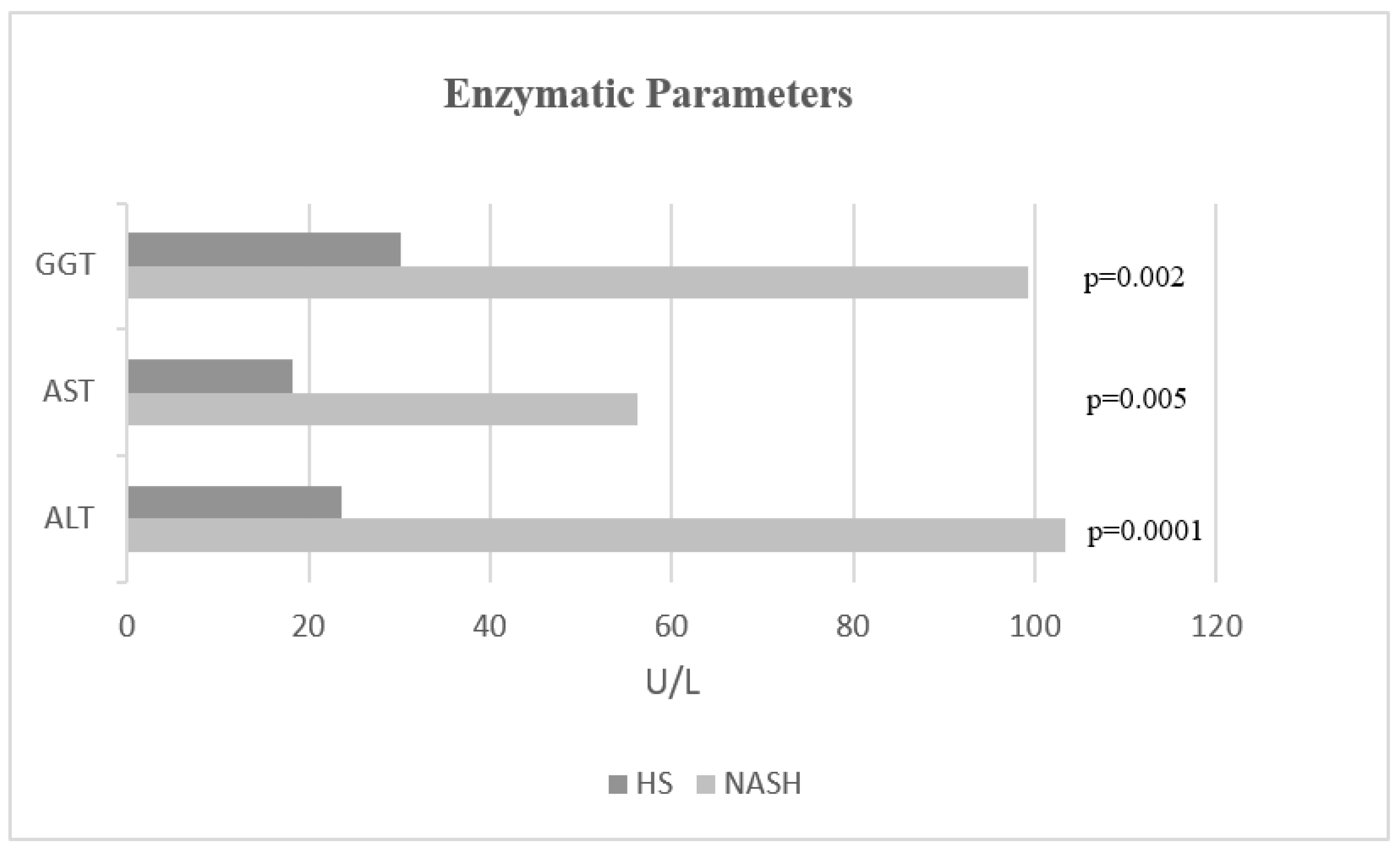

| ALT (U/L) | 43.89±44.39 | 23.61±9.19 | 103.4±54.26 | 0.0001* |

| AST (U/L) | 28.33±23.64 | 18.18±5.11 | 56.26±32.80 | 0.005* |

| GGT (U/L) | 47.74±47.58 | 30.15±21.21 | 99.33±70.17 | 0.002⃰ |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.48±0.60 | 4.66±0.44 | 4.42±0.35 | 0.19 |

| Parameter | Incidence and Mean Value in Patients with NAFLD and T2DM | Incidence and Mean Value in Patients with HS and T2DM | Incidence and Mean Value in Patients with NASH and T2DM | Statistical Significance p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.35±1.58 | 13.09±1.64 | 14.1±1.27 | 0.03 ⃰ |

| WBC (no/mm3) | 7901±1893 | 8066±1945 | 7415±1635 | 0.25 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 59.37±7.88 | 59.67±0.94 | 58.46±6.13 | 0.62 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 29.16±8.13 | 28.65±4.10 | 30.65±6.96 | 0.42 |

| Monocytes (%) | 6.17±1.38 | 5.99±1.72 | 6.72±1.47 | 0.07 |

| Platelets (no/mm3) | 245502±62489 | 251992±91923 | 226666±77524 | 0.45 |

| MLR | 0.22±0.07 | 0.21±0.07 | 0.23±0.07 | 0.62 |

| NLR | 2.37±0.93 | 2.31±0.97 | 2.53±0.80 | 0.45 |

| PDW (%) | 41.19±14.37 | 41.98±12.62 | 38.87±18.36 | 0.47 |

| MPV (fL) | 9.86±1.03 | 9.92±0.92 | 9.68±1.28 | 0.44 |

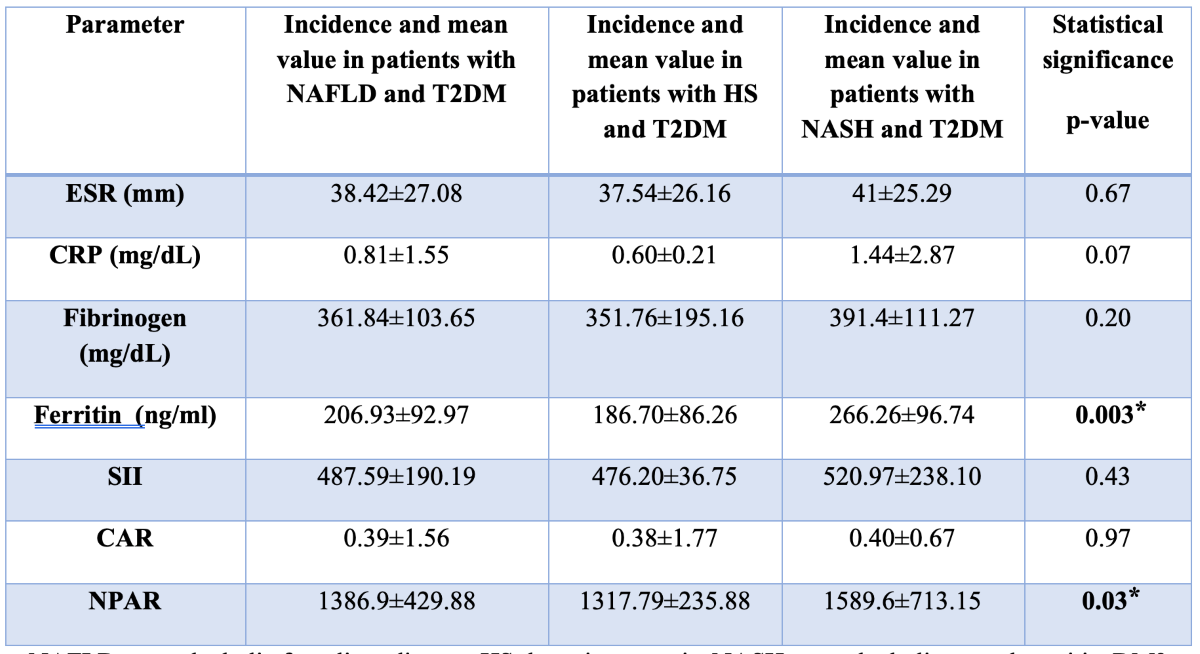

| Parameter | Incidence and mean value in patients with NAFLD and T2DM | Incidence and mean value in patients with HS and T2DM | Incidence and mean value in patients with NASH and T2DM | Statistical significance p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESR (mm) | 38.42±27.08 | 37.54±26.16 | 41±25.29 | 0.67 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.81±1.55 | 0.60±0.21 | 1.44±2.87 | 0.07 |

| Fg (mg/dL) | 361.84±103.65 | 351.76±195.16 | 391.4±111.27 | 0.20 |

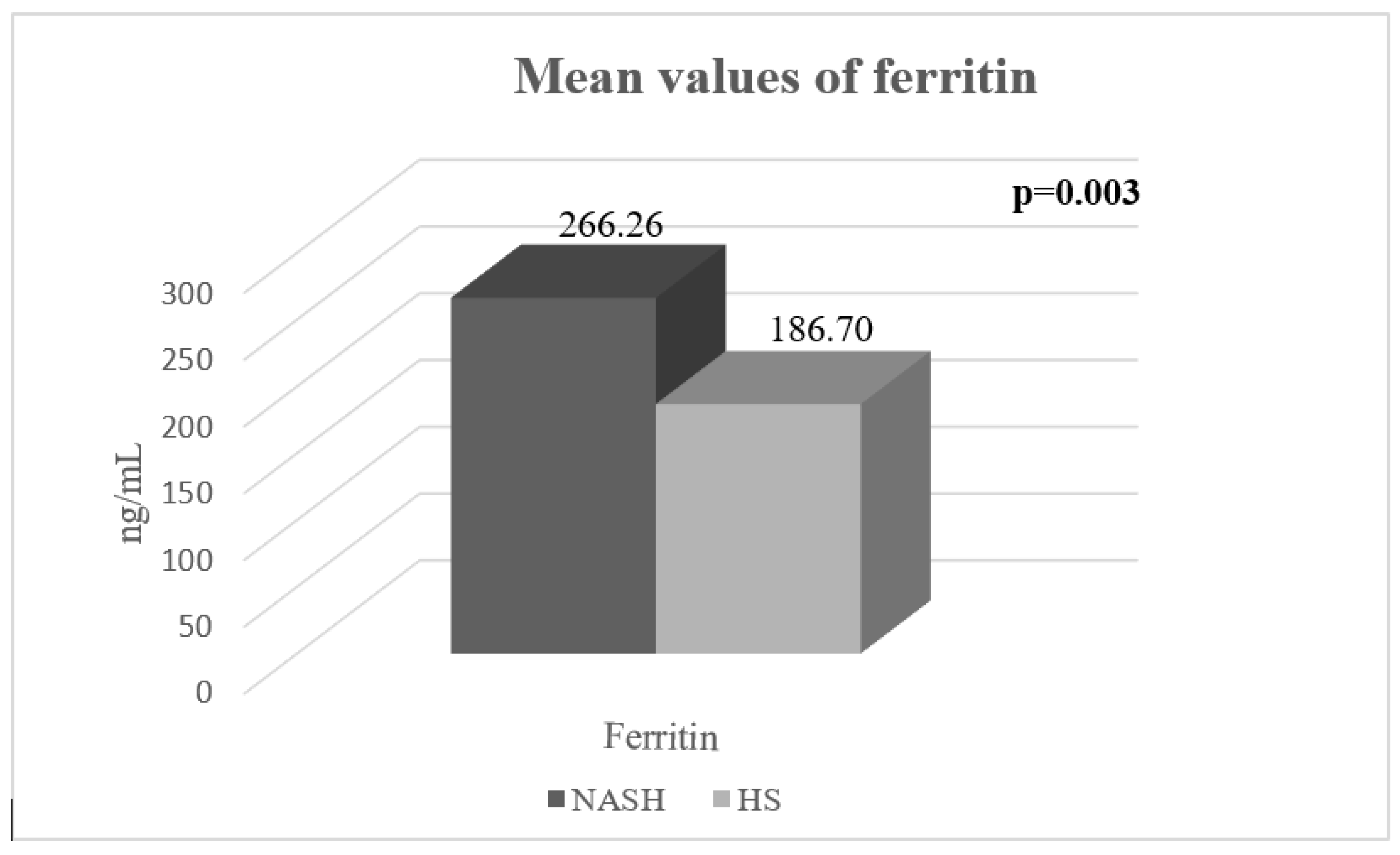

| SF (ng/ml) | 206.93±92.97 | 186.70±86.26 | 266.26±96.74 | 0.003 ⃰ |

| SII | 487.59±190.19 | 476.20±36.75 | 520.97±238.10 | 0.43 |

| CAR | 0.39±1.56 | 0.38±1.77 | 0.40±0.67 | 0.97 |

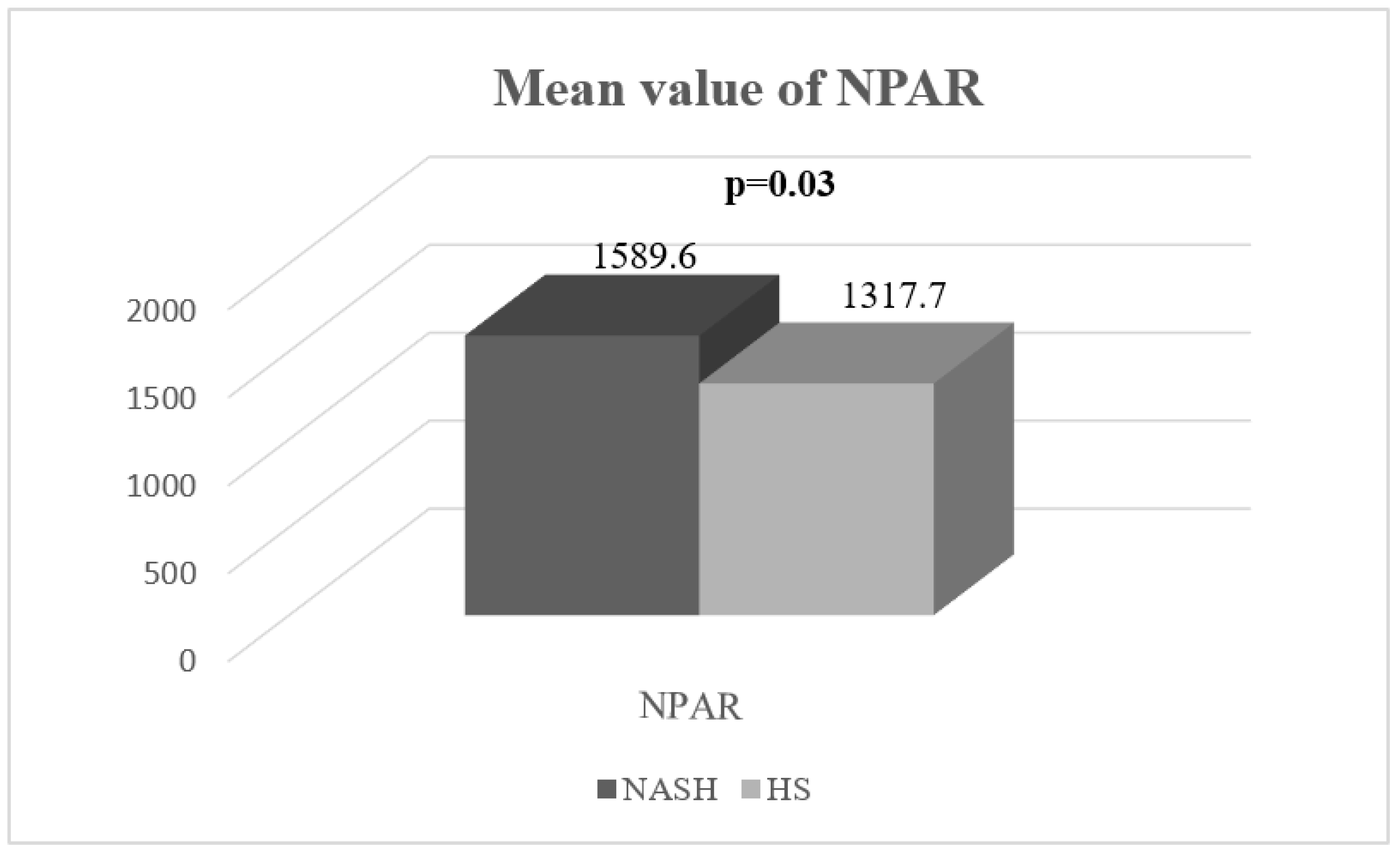

| NPAR | 1386.9±429.88 | 1317.79±235.88 | 1589.6±713.15 | 0.03 ⃰ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).