INTRODUCTION

Influenza is an acute viral respiratory disease, highly contagious, transmitted through droplets and associated with both seasonal antigenic drifts and shifts with risk of global pandemics. The virus emerges from zoonotic reservoirs in aquatic birds and bats, and human transmission usually is derived from poultry or porcine prior infection (1).

The main factors associated with higher morbidity and mortality from influenza are age (< 5 years old, > 65 years old); pregnancy, immunodeficiency, medical co-morbidities, and genetic susceptibility (1).

Pregnant women are at increased risk of influenza-associated complications and are identified as a priority group for seasonal and pandemic flu vaccination. Recent seasonal influenza epidemics have shown that pregnant women had a meaningfully higher risk of hospitalization compared with non-pregnant women. (2). The highest hospitalization rates occur during the third trimester of pregnancy, at which time pregnant women are 3-4 times more likely to be hospitalized with a cardiopulmonary illness during influenza season compared with postpartum women (3,4).

Transplacental transmission of the 2009 AH1N1 virus was alleged in some cases, but definitive evidence was not available (5). However, reports from the AH1N1 pandemic indicate that influenza during pregnancy increases the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. A study of 256 women who were hospitalized in the United Kingdom with 2009 AH1N1 virus infection during pregnancy evidenced a significantly increased perinatal mortality rate (39 per 1000 total births [95% CI, 19 – 71] among women with prenatal influenza), compared with 7 per 1000 (95% CI, 3–13) among the comparison group without 2009 H1N1. Risk factors for preterm delivery were third-trimester infection, admission to an intensive care unit, and secondary pneumonia that accompanied 2009 H1N1 (6). Several studies have reported similar results (7). Vaccination of pregnant women confers protection to both the women against severe disease (8), and to the newborns thru transplacental antibodies during pregnancy (9), as well as after delivery via breastfeeding (10).

Despite the great efforts to increase the coverage of maternal immunization against influenza, this proves difficult. Copious published data have described the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine; nevertheless, it still is not reaching the desired coverage rates in pregnant women anywhere globally. Several factors contribute to this. Lack of proper knowledge regarding the disease and the vaccine may be one of the primary contributors to this problem.

In Mexico, influenza vaccination in pregnancy is a priority, and it is of free access to all pregnant women that wish to acquire it. However, as a free vaccine for public settings its availability is limited (11). Nonetheless, national data regarding influenza vaccination rates, influenza-related complications and deaths during pregnancy is not publicly available.

The Mexican prenatal and obstetric care falls under the care of the Obstetricians (OBGYNs) and Family Physicians (FPs), they oversee the follow up of the pregnancy. The national official Mexican norm (NOM-007-SSA) promotes that all pregnant women of low risk receive a minimum of 5 prenatal consultations and a maximum of 8 consultations (12,13).

During prenatal care, the providers of obstetric care must take a complete immunization history, but many women do not recall nor have a record of their lifetime vaccinations. Ideally, the woman should have her complete and updated vaccination schedule before pregnancy, and this would avoid the concern about doing it during pregnancy.

We hypothesized that Mexican healthcare providers (HCP) for pregnant women (OBGYNs and FPs) are not aware of Influenza complications during pregnancy (and for the newborn) neither the benefits of influenza vaccination in this high-risk group.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional study to evaluate the knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes of Mexican healthcare providers (OBGYNs and FPs), on influenza disease, seasonal influenza immunization of pregnant women, and their current recommendation, through a survey. We focused on these HCPs as they are traditionally the ones in charge of the maternity care in Mexico, and as recommended by the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS) (14).

Survey Design and Delivery

We used the Google Survey® platform to create, send, and collect our questions and responses. The collection of responses occurred over two months (February-March 2020). The survey design was composed of 32 questions divided into four sections. Section one included demographic characteristics of the population. All answers were of multiple choice. Section two included 11 questions on knowledge about seasonal influenza disease, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, vaccination, and impact on pregnant women. Answers were Yes, No, or I do not know.

Sections three and four included a Likert scale questionnaire (15) around beliefs and attitudes related to seasonal influenza vaccination in the pregnant population. We used both multiple-choice (Yes, No, Unknown), and open questions.

We had support from the College of Gynecology and Obstetrics of Tijuana, AC, Mexico (Colegio de Ginecología y Obstetricia de Tijuana), and the Family Medicine Specialty Association of Baja California, AC, Mexico (Asociación de Especialistas en Medicina Familiar de Baja California, AC). They distributed our survey among their current members and colleagues in other states of the country on condition of confidentiality. Both medical societies sent the survey through email to all members between February and March 2020, and only the responses obtained during that period were considered for this study.

We used Microsoft Excel® to conduct the descriptive-qualitative analysis. We tabulated and analyzed all data by gender, medical specialty, years of experience, and place of work. An Odds Ratio (OR) analysis was conducted for each question to determine statistically significant differences among the responses of the OBGYNs and FPs.

RESULTS

A total of 206 HCP participated in the survey, 98 (47.6%) OBGYNs and 108 (52.4%) FPs; 131 (63.6%) of respondents were female and 75 (36.4%) males. With respect to geography, most 134/206 (65.4%) were from the northern state of Baja California, followed by Mexico City with 20 (9.3%); 52 responders (25.3%) came from other states covering the north, center, and south of Mexico.

Data regarding their primary medical practice institution showed that 76 (37%) work predominantly for the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS), 69 (34%) in the Private Sector (PS), and 31 (15%) in the Secretary of Health (SSa) Sector

Most respondents had 1-5 (115/206; 56%), 6-10 (29/206; 14%), and (62/206; 30%) years of work experience. The average number of pregnant women seen on a daily based was 12 (range: 5-20), resulting in a total of 2,472 daily pregnancy consultations among our study population. Considering this is a study-related to seasonal influenza immunization, we asked all participants if they received their seasonal flu vaccination. The results showed that 83% of FPs and 66% of OBGYNs were immunised prior to the flu season.

All responses to the survey questions can be found in

Table 1. Here we highlight the most important findings. 199 (96.6%) of our participants knew about seasonal influenza and its cause. Nevertheless, only 151 (73.3%) correctly identified the different types of influenza viruses that cause seasonal epidemics and outbreaks in humans; 20.4% responded that in their opinion the clinical picture of influenza disease is like a common cold, rarely severe, and does not cause death; 99% identified correctly the high-risk groups for influenza complications; and 10.1% stated that they were not aware that infection – mostly milder - could occur even if vaccinated.

Most participants (180/206; 86.4%) answered correctly that PCR is the standard tool to confirm influenza infection. With respect to treatment 150 (72.8%) had the correct answer, and 56 (27.2%) didn’t. As for preventive measures, 197 (95.6%) of them correctly respond that vaccination is the best way to prevent infection and disease.

152 (73.8%) of our population study agrees that pregnant women are more frequently hospitalized due to influenza when compared with non-pregnant women whilst 17% disagreed and 9.2% did not know. Moreover, 100 (48.5%) acknowledged that adverse effects due influenza infection can affect the fetus but 106 (51.5%) considered this to be false or not knowing about it. 45 (22%) believed that contracting influenza disease and its complications are exclusive for pregnant women with concomitant comorbidities, such as diabetes, obesity, hypertension, autoimmune diseases, among others.

As for the appropriate time to vaccinate a pregnant woman, 117 (56.8%) replied that vaccination can occur any time during pregnancy; 49 (23.8%) replied that could take place during the 2nd trimester, 27 (13.1%), 1st trimester, and 13 (6.3%), the 3rd trimester, respectively.

In the beliefs section, more than half (61%) responded that they either strongly disagree, disagree, or didn’t know that pregnancy alone is not a risk factor for developing influenza complications; but 39% reported the opposite. Only 22% agreed that influenza disease in a pregnant woman confers a health or developmental risk to the fetus, and a minority (6%) believed that “influenza vaccine is NOT safe and can cause influenza infection”.

More than half (66%) reported having treated a pregnant woman with influenza and believed that seasonal influenza disease can be harmful in this population. Conversely, the remaining 34% replied not to have contact somehow with these cases and responded to ignore the severity of the disease in this population. 198 (96.1%) considered that immunization against influenza during pregnancy is a safe and effective preventive intervention.

62 (30%) physicians believed that influenza vaccination only conferred protection to the mother, but not to the fetus, and this assumption was equivalent between OBGYNs (32.3%) and FP (31.3%). In addition, 33 (16%) did not know whether influenza vaccination protected both the mother and the baby, a mistaken assumption found higher in FP (21.6%) than in OBGYNs (12.74%).

When responding to their actual clinical practices, 98.1% recommend influenza vaccination during pregnancy. 79.6% responded that they always (56.8%), or very often (22.8%) checked the vaccination status of their patients. As for the appropriate time during pregnancy when they feel comfortable recommending the influenza vaccination, 89.3% considered that this could be either in the first or second trimester (44.2%, and 45.1%, respectively). The remaining 10.7% preferred the third trimester for vaccination.

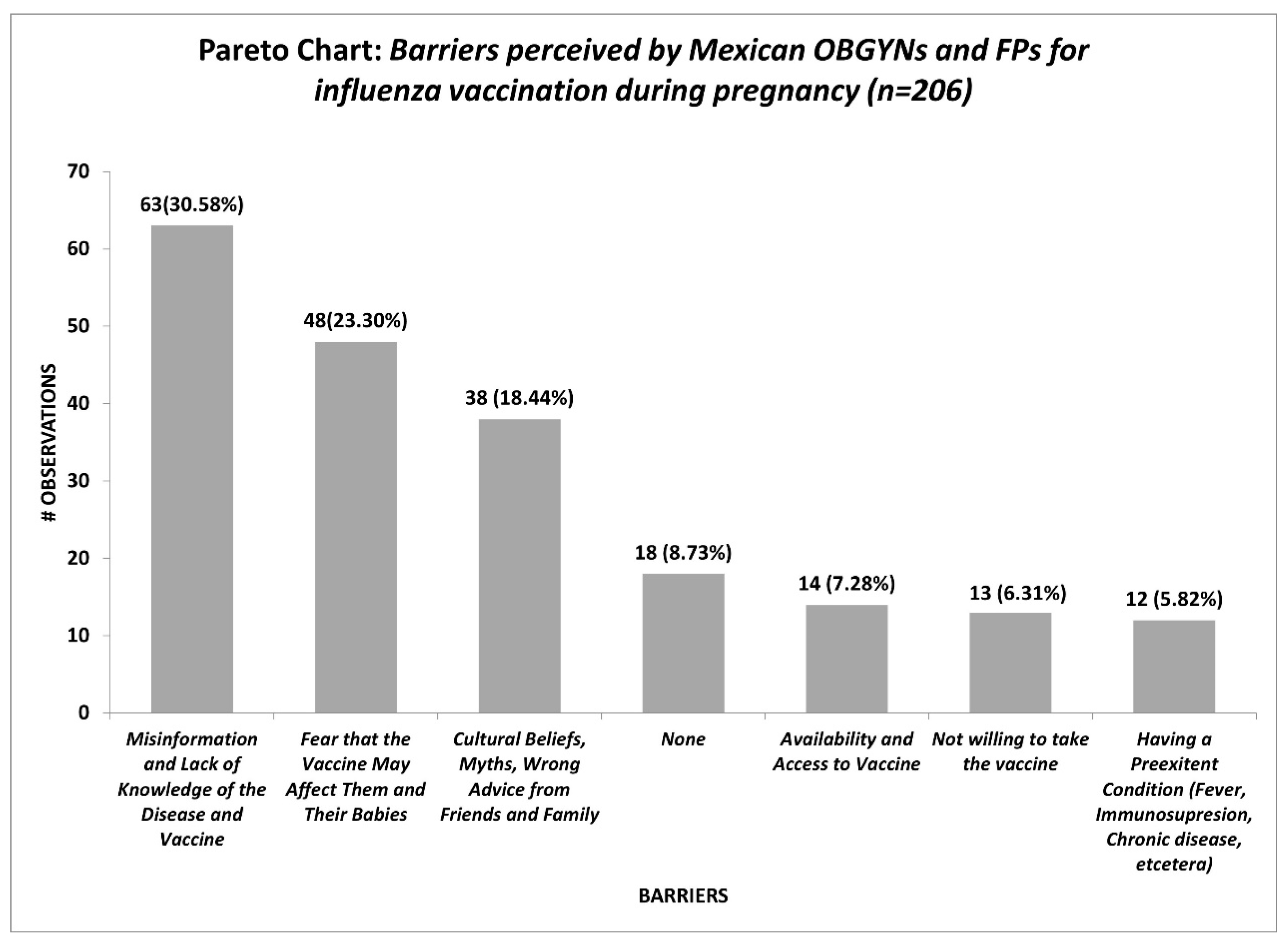

The reported barriers by OBGYNs and FPs concerning influenza vaccination during pregnancy are shown in Figure 1. Misinformation and lack of knowledge of the disease and vaccine (30.58%), fear that the vaccine may affect them and their babies (23.3%), and cultural beliefs, myths, wrong advice from friends and family (18.44%) represent the most significant barriers by the medical providers.

An interesting fact was that when comparing individual vaccination by medical specialty, we found that by only looking to the raw data FPs tend to get more vaccinated against influenza than the OBGYNs, nevertheless, when calculating the OR the results withdraw a non-statistically significant difference among both groups (OR=1.25, 95% CI [0.82-1.91], P-value [0.28]). And no other statistically significant differences were found among both groups.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first investigating the knowledge, beliefs, and practices associated with influenza vaccination during pregnancy in a group of maternity care providers in Mexico. OBGYNs and FPs are the cornerstones for healthcare in pregnant women in Mexico, and they play an essential role in the current recommendation and implementation of all preventive measures in pregnancy, especially in vaccine uptake.

Even though influenza vaccination in pregnant women has been implemented since 2004 in Mexico, it was not until 2009 after the Influenza AH1N1 pandemic that more significant efforts were made to recommend its use in this high-risk population actively (16, 17). Nevertheless, despite these efforts, influenza vaccine coverage among the pregnant population remains unknown in Mexico. Reports on national coverage suggest that influenza vaccine coverage is as low as 56.5% for the whole population (18).

In our study, the majority (98.1%) of the surveyed HCPs were aware and supportive of the current recommendations for influenza vaccination for pregnant women. The above discovery is consistent with the results of other studies from the USA and Europe showing high rates of recommendation during pregnancy by physicians (19–21). Nevertheless, in those same studies, they found that influenza vaccine vaccination among these medical providers was only of 75% despite their recommendation.

The overall knowledge about influenza illness and vaccines was somehow high (79.46%) among both populations. Areas of opportunitie for education are impact of influenza infection on the fetus (51.5% incorrect); safety of vaccination in pregnancy (42.8% incorrect); timing of vaccination during pregnancy (43.2% incorrect); pregnancy is a risk factor for being hospitalized due to influenza complications (26.2% incorrect).

Based on these knowledge gaps our responders might be recommending influenza vaccination with varying levels of clarity and conviction. Comparable findings have been reported in previous studies that describe that other prenatal care providers have fluctuating levels of knowledge about influenza vaccination during pregnancy (22-25). The latter is noteworthy, as increased levels of knowledge are linked with higher rates of influenza vaccination in pregnant women (26).

We also noted that the reported knowledge was being contradicted in some areas in the beliefs section. For example, whilst 99% of the HCP answered knowing the high-risk groups, yet, in the beliefs section, 48% reported not considering pregnancy as a high-risk factor, and 22% believe that complications due to influenza among pregnant women only occur in those who have chronic conditions, such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiac disorders, among others.

Although the increased risk of severe complications and mortality of influenza infection during pregnancy is well documented, for both the expectant mother and the fetus (27), this remains a critical gap of knowledge in our responders since 22% replied believing that no risk was conferred to the fetus when the mother gets influenza. We assume this gap of knowledge might be linked with the fact that only 34% acknowledged never treating a pregnant woman with influenza, and for that, they doubt the severity of this disease in this population. Esposito et al (28) reported similar outcomes, where 40.6% of the OBGYNs acknowledge not considering influenza as a potentially severe disease.

Another discrepancy noted was the vaccination timing during pregnancy: 58.6% reported in the knowledge section that any time is appropriate to do so but75.8% answered the same question correctly in the beliefs section. The biggest difference came from answers related to knowledge vs. beliefs regarding protection induced by vaccination: 30% believed that the vaccine only confers protection to the mother but not to the baby. Yet, 96.1% responded in the beliefs section that the vaccine is an effective measure to prevent influenza, reduces the risk of hospitalization (92.8%), and that it is safe and effective (94%) for both the mother and the newborn. These results reflect a clear dealignment between what physicians know and believe when it comes to influenza vaccination during pregnancy, highlighting that knowledge by its own will not always drives clinical practices.

Variability in the responses makes us infer that our study population does not possess a clear understanding of the safety profile of the influenza vaccine nor the impact of the severity of influenza disease in the pregnant population. They pose a good theoretical knowledge; however, when implementing that knowledge into their daily practices, their practice is not in line with what they know. Efforts are needed to align their knowledge with their beliefs and practices, as this denotes a barrier in proper recommendations. The main reported barriers from the HCP perspective regarding the uptake of influenza vaccine in their pregnant populations were misinformation and lack of knowledge of both the disease and the vaccine 63/206 (30.58%), followed by the expressed fear from pregnant to their HCP that the vaccine may affect them and their babies 48/206 (23.3%). Added to the fact that social-cultural beliefs, myths, and wrong advice from friends and family have a strong influence on them for accepting the immunization.

Initially, we were expecting that the main barrier was that the pregnant woman did not want the vaccine, however, this potential barrier to vaccination was reported by 13/206 (6.31%) of our respondents.

Similar findings were reported by Maisa et al. (29) were information and knowledge was the primary barrier, followed by the influence of others, the acceptance and trust in both the HCP and vaccine, the fear and distrust, the responsibility for the baby, and lastly access to vaccination.

As a final point to this, perceived barriers are essential to be identified since, as HCP or even as patients, we often think that access to care and willingness are the main barriers when they are the opposite; they just represent the tip of the iceberg. Conducting an appropriate root cause analysis of this problem by using the different tools for continuous process improvement is something that should be compulsorily promoted.

Our study has limitations: the geographic distribution of responders is not representative of the HCP population distribution in Mexico, it is a small sample; and selection bias cannot be excluded as there was no control on whom the Societies contacted and who not. Future studies need to consider expanding the scope to include more HCP from different states and medical institutions. The distribution of medical specialties and gender was not representative of the current situation in Mexico either.

Based on an estimated 2,472 daily pregnancy consultations among our responders which is a strength of this study, we gathered and report here valuable information on where to direct the efforts to improve vaccine uptake in pregnant women since our HCP have a vast area of opportunity to reach a high number of patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results highlight an evident discrepancy in knowledge vs. beliefs regarding influenza disease and vaccination during pregnancy between physicians in care of pregnant women.

These findings underline that knowledge alone it is not sufficient to make proper recommendations for influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Hence, understanding drivers of beliefs and attitudes will be essential to ensure a more effective way to educate HCP resulting in an improved clinical practice and recommendations from OBGYNs and FP to all pregnant women, potentially leading to an enhanced influenza vaccine uptake in pregnancy.

Factual information alone does not always result in the maintenance of long-term health behavior changes, therefore, continued monitoring and evaluation of all programs directed to HCP with more information about influenza vaccination will be essential in creating long-term changes.

Funding

This study did not receive any external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical considerations

Considering that this study was an online only survey, we implemented “Implied Consent”, in which by choosing “I accept to participate in the survey”, the following was stated: “Your willingness to return the completed questionnaire indicates your consent to participate in this study” (

https://www.research.psu.edu/orp). In addition, based on Article 17, first paragraph, of the current Mexican Regulation for Health Research (REGLAMENTO DE LA LEY GENERAL DE SALUD EN MATERIA DE INVESTIGACION PARA LA SALUD) updated in 2014, anonymous surveys are considered of no risk (

https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/regley/Reg_LGS_MIS.pdf).

References

- Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. The Lancet. 2017 Aug:390(10095):697–708. [CrossRef]

- Polyzos KA, Konstantelias AA, Pitsa CE, Falagas ME. Maternal Influenza Vaccination and Risk for Congenital Malformations: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Nov;126(5):1075–84. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ. Influenza and Pregnancy: No Time for Complacency. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan;133(1):23–6. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Uyeki TM. Effects of influenza on pregnant women and infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Sep;207(3):S3–8. [CrossRef]

- Laibl VR, Sheffield JS. Influenza and Pneumonia in Pregnancy. Clin Perinatol. 2005 Sep;32(3):727–38. [CrossRef]

- Gozde Kanmaz H, Erdeve O, Suna Oğz S, Uras N, Çelen Ş, Korukluoglu G, et al. Placental Transmission of Novel Pandemic Influenza a Virus. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2011 Aug 30;30(5):280–5. [CrossRef]

- Valvi C, Kulkarni R, Kinikar A, Khadse S. 2009H1N1 Infection in a 1-day-old neonate. Indian J Med Sci. 2010 Dec;64(12):549–52. [CrossRef]

- Kachikis A, Englund JA. Maternal immunization: Optimizing protection for the mother and infant. J Infect. 2016 Jul;72:S83–90. [CrossRef]

- Maertens K, Caboré RN, Huygen K, Vermeiren S, Hens N, Van Damme P, et al. Pertussis vaccination during pregnancy in Belgium: Follow-up of infants until 1 month after the fourth infant pertussis vaccination at 15 months of age. Vaccine. 2016 Jun;34(31):3613–9. [CrossRef]

- Maertens K, De Schutter S, Braeckman T, Baerts L, Van Damme P, De Meester I, et al. Breastfeeding after maternal immunisation during pregnancy: Providing immunological protection to the newborn: A review. Vaccine. 2014 Apr;32(16):1786–92. [CrossRef]

- Vacunacion en la embarazada – Mexico Gobierno General – Guia de reference rapida. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/http://www.cenetec-difusion.com/CMGPC/IMSS-580-12/RR.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Thompson MG, Kwong JC, Regan AK, Katz MA, Drews SJ, Azziz-Baumgartner E, et al. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Influenza-associated Hospitalizations During Pregnancy: A Multi-country Retrospective Test Negative Design Study, 2010–2016. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Apr 24;68(9):1444–53. [CrossRef]

- McMillan M, Porritt K, Kralik D, Costi L, Marshall H. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy: a systematic review of fetal death, spontaneous abortion, and congenital malformation safety outcomes. Vaccine. 2015 Apr 27;33(18):2108–17. [CrossRef]

- Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Likert-Scale (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Guia Practica Clinica, Control prenatalcon atención centrada en la paciente. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.imss.gob.mx/sites/all/statics/guiasclinicas/028GER.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Hurtado-Ochoterena CA, Matias-Juan NA. Historia de la vacunación en Mexico. Vac Hoy Rev Mex Puer Pediatr. 2005 Nov; 13:74.

- Kuri-Morales PA, Díaz del Castillo-Flores G, Castañeda-Prado A, Pacheco-Montes SR. Clinical-epidemiological profile of deaths from influenza with a history of timely vaccination, Mexico 2010-2018. Gac Mexico. 2020 Feb 24;155(5):3722. [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Valdivia B, Mendoza-Alvarado LR, Palma-Coca O, Hernández-Ávila M, Téllez-Rojo Solís MM. Encuesta Nacional de Cobertura de Vacunación (influenza, neumococo y tétanos) en adultos mayores de 60 años en México. Salud Pública México. 2012 Feb;54(1):39–46.

- Maertens K, Braeckman T, Top G, Van Damme P, Leuridan E. Maternal pertussis and influenza immunization coverage and attitude of health care workers towards these recommendations in Flanders, Belgium. Vaccine. 2016 Nov 11;34(47):5785–91. [CrossRef]

- Vishram B, Letley L, Hoek AJV, Silverton L, Donovan H, Adams C, et al. Vaccination in pregnancy: Attitudes of nurses, midwives and health visitors in England. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2018 Jan 2;14(1):179–88. [CrossRef]

- Arao RF, Rosenberg KD, McWeeney S, Hedberg K. Influenza Vaccination of Pregnant Women: Attitudes and Behaviors of Oregon Physician Prenatal Care Providers. Matern Child Health J. 2015 Apr 1;19(4):783–9. [CrossRef]

- Tong S, Zhu X, Li Y, Shi M, Zhang J, Bourgeois M, et al. New World Bats Harbor Diverse Influenza A Viruses. Subbarao K, editor. PLoS Pathog. 2013 Oct 10;9(10):e1003657. [CrossRef]

- Broughton DE, Beigi RH, Switzer GE, Raker CA, Anderson BL. Obstetric health care workers’ attitudes and beliefs regarding influenza vaccination in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Nov;114(5):981–7. [CrossRef]

- Lu AB, Halim AA, Dendle C, Kotsanas D, Giles ML, Wallace EM, et al. Influenza vaccination uptake amongst pregnant women and maternal care providers is suboptimal. Vaccine. 2012 Jun 8;30(27):4055–9. [CrossRef]

- Kissin DM, Power ML, Kahn EB, Williams JL, Jamieson DJ, MacFarlane K, et al. Attitudes and practices of obstetrician-gynecologists regarding influenza vaccination in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Nov;118(5):1074–80. [CrossRef]

- Eppes C, Wu A, Cameron KA, Garcia P, Grobman W. Does obstetrician knowledge regarding influenza increase HINI vaccine acceptance among their pregnant patients? Vaccine. 2012 Aug;30(39):5782–4. [CrossRef]

- Omer SB, Bednarczyk R, Madhi SA, Klugman KP. Benefits to mother and child of influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2012 Jan;8(1):130–7. [CrossRef]

- Esposito S, Tremolati E, Bellasio M, Chiarelli G, Marchisio P, Tiso B, et al. Attitudes and knowledge regarding influenza vaccination among hospital health workers caring for women and children. Vaccine. 2007 Jul;25(29):5283–9. [CrossRef]

- Maisa A, Milligan S, Quinn A, Boulter D, Johnston J, Treanor C, et al. Vaccination against pertussis and influenza in pregnancy: a qualitative study of barriers and facilitators. Public Health. 2018 Sep;162:111–7. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices of HCPs regarding Influenza vaccination during Pregnancy, in Mexico.

Table 1.

Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices of HCPs regarding Influenza vaccination during Pregnancy, in Mexico.

| Questions |

Responses |

All |

(%) |

| Knowledge Section |

| Seasonal influenza disease is an acute respiratory infection caused by the influenza virus, which circulates throughout the world? |

True

False

I do not know |

199

5

2 |

(96.6)

(2.4)

(1) |

| There are 4 types of seasonal influenza viruses, A, B, C, and D. But only type A and B viruses are responsible for seasonal outbreaks and epidemics of the disease. |

True

False

I do not know |

151

31

24 |

(73.3)

(15)

(11.7) |

| The clinical picture of Influenza disease is like the common flu, is rarely severe, and does not cause any death. |

True

False

I do not know |

164

42

0 |

(79.6

(20.4)

(0) |

| All age groups can be affected by seasonal influenza. However, there are higher risk groups that develop the disease and its complications. Such are: Children under 5 years of age, pregnant women, older adults, individuals with chronic diseases. |

True

False

I do not know |

204

1

1 |

(99)

(0.5)

(0.5) |

| The onset of seasonal influenza symptoms may occur suddenly or progress more slowly, and patients who received the vaccine may have milder symptoms. |

True

False

I do not know |

185

13

8 |

(89.8)

(6.3)

(3.9) |

| The standard criterion for confirming influenza virus infection remains a polymerase chain reaction with reverse transcription (PCR) or viral culture of nasopharyngeal or throat secretions. |

True

False

I do not know |

178

15

13 |

(86.4)

(7.3)

(6.3) |

| Antiviral medications for seasonal influenza include oseltamivir, zanamivir, and baloxavir marboxil. |

True

False

I do not know |

150

37

19 |

(72.8)

(18)

(9.2) |

| The most effective way to prevent infection and disease is through annual vaccination against the Influenza virus of all individuals at risk. |

True

False

I do not know |

197

9

0 |

(95.6)

(4.4)

(0) |

| Pregnant women tend to be frequently hospitalized due to the development of more severe illness and development of complications, and they can even die due to seasonal influenza, than women who are not pregnant. |

True

False

I do not know |

152

35

19 |

(73.8)

(17)

(9.2) |

| Some of the adverse effects of influenza infection in the fetus are the restriction of fetal growth, fetal distress, neural tube defects, preterm birth, increased fetal mortality. |

True

False

I do not know |

100

55

51 |

(48.5)

(26.7)

(24.8) |

| When is the best time to vaccinate pregnant women against seasonal influenza? |

Any Trimester

1st

2nd

3rd

|

117

49

27

13 |

(56.8)

(23.8)

(13.1)

(6.3) |

| Beliefs Section |

| Pregnancy per se is NOT a risk factor for developing influenza disease and its complications. |

Strongly Agree

Agree

Neutral

Disagree

Strongly disagree |

47

34

18

43

64 |

(22.8)

(16.5)

(8.7)

(20.9)

(31.1) |

| Influenza disease does NOT confer any health or developmental risk to the fetus. |

Strongly Agree

Agree

Neutral

Disagree

Strongly disagree |

14

17

15

82

78 |

(6.8)

(8.3)

(7.3)

(39.8)

(37.9) |

| The influenza vaccine is NOT safe and can cause influenza infection. |

Strongly Agree

Agree

Neutral

Disagree

Strongly disagree |

1

1

11

63

130 |

(0.5)

(0.5)

(5.3)

(30.6)

(63.1) |

| I have never treated a pregnant patient with influenza, so doubt the severity of this disease in this population. |

Strongly Agree

Agree

Neutral

Disagree

Strongly disagree |

16

27

27

55

81 |

(7.8)

(13.1)

(13.1)

(26.7)

(39.3) |

| Do you consider that vaccination against the influenza virus in pregnant women is a SAFE and EFFECTIVE practice to prevent the disease? |

Strongly Agree

Agree

Neutral

Disagree

Strongly disagree |

155

43

5

2

1 |

(75.2)

(20.9)

(2.4)

(1.0)

(0.5) |

| Only pregnant women with chronic degenerative diseases (DM, HBP, Lupus, etcetera.) are prone to contracting Influenza disease and its complications. |

Strongly Agree

Agree

Neutral

Disagree

Strongly disagree |

22

19

4

66

95 |

(10.7)

(9.2)

(1.9)

(32)

(46.1) |

| Influenza vaccination in pregnant women only gives protection to the mother, but not to the baby. |

Strongly Agree

Agree

Neutral

Disagree

Strongly disagree |

22

19

4

66

95 |

(10.7)

(9.2)

(1.9)

(32)

(46.1) |

| Pregnant women who were vaccinated against influenza reduce their risk of being hospitalized due to complications. |

Strongly Agree

Agree

Neutral

Disagree

Strongly disagree |

133

58

4

7

4 |

(64.6)

(28.2)

(1.9)

(3.4)

(1.9) |

| The Influenza vaccine can be applied in pregnant women during any trimester of pregnancy. |

Strongly Agree

Agree

Neutral

Disagree

Strongly disagree |

113

43

13

25

12 |

(54.9)

(20.9)

(6.3)

(12.1)

(5.8) |

| Practices Section |

| Do you recommend and promote influenza vaccination during pregnancy? |

Yes

No |

202

4 |

(98.1)

(1.9) |

| Do you offer influenza vaccination among all your patients regardless of their pregnancy status (pregnant or not pregnant)? |

Yes

No |

177

29 |

(85.9)

(14.1) |

| Usually during which pregnancy trimester do you promote or apply influenza vaccination? |

1st

2nd

3rd

|

91

93

22 |

(44.2)

(45.1)

(10.7) |

| Do you check the immunization status of all your patients? |

Always

Very often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never |

117

47

26

5

11 |

(56.8)

(22.8)

(12.6)

(2.4)

(5.3) |

| Would you be interested in learning more about the benefits of influenza vaccination during pregnancy? |

Yes

No |

198

8 |

(96.1)

(3.9) |

| What challenges or barriers do you consider play a role in influenza vaccine uptake during pregnancy? |

Open question |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).