Submitted:

03 July 2023

Posted:

04 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. State of art

2.1. Corporate reputation and reputation risk management

- 1)

- A number of factors outside the control of the company, such as competitor and customer behavior, market conditions, etc., affect the extent of harm.

- 2)

- Their chance of occurring is too complex to anticipate, leading to the evaluation becoming meaningless when the quantitative expression of risk is calculated. It is associated with human behavior, which makes it challenging to include in assessment models; t

- 3)

- There is no obvious owner of this risk, making it unclear whose role it is to ensure that it is being monitored.

2.2. Corporate’s reputation and CSR strategy

2.3. Patent rights and CSR strategy

- issues related to the reward of inventors - once the creator has put in a lot of effort, money, time, property, talent, etc., he deserves the appropriate reward, namely protection of his invention. This point of view has been advocated in many court decisions commenting on the risk taken by the inventor and his inability to recoup the money and time invested by making his invention freely available for production on the market.

- optimizing productivity models - Harold Demsetz (1967) argued many years ago that copyright and patent systems have an important role to play in enabling potential producers of intellectual products to know what consumers want and thus to direct productive efforts in directions most likely to enhance consumer welfare. Sales and licenses will ensure that goods get into the hands of people who want them and are able to pay for them. Only in the rare situations where transaction costs would prevent such voluntary exchanges could intellectual property owners be denied absolute control over the uses of their works, either through direct privilege (such as the fair use doctrine) or through a system of compulsory licensing.

- competing invention - its purpose is to eliminate or reduce the tendency of intellectual property rights to encourage duplicative or uncoordinated inventive activity. The basis for this approach was laid by a group of economists, led by Yoram Barzel (1997), who studied the ways in which competition among firms compounds the impact of the patent system on inventive activity.

3. Patent monopoly for corporate’s reputation of high-tech companies

3.1. Company benefits from patenting technologies

- market exclusivity: patents give high-tech businesses a period of exclusivity, usually 20 years from the date of filing, during which they can make use of their inventions without opposition. This exclusivity enables businesses to profit from the commercialization of their inventions, as well as to recoup their investment in R&D. Further strengthening the patent holder's position in the market, it acts as a barrier to entry for potential rivals.

- revenue generation: opportunities for licensing and monetization - high-tech companies frequently license their patented technologies to other businesses, enabling them to generate additional revenue streams. A business can authorize the use of its patented technology by third parties through licensing agreements in exchange for licensing fees or royalties.- Thus, patents can develop into priceless assets that support a business.

- strategic advantage: a strong patent portfolio can give high-tech companies a strategic advantage and give them more negotiating power. It demonstrates their technological know-how, strengthens their reputation as an innovator, and aids in luring investors and partners. Furthermore, companies can use patents as negotiating tools to obtain advantageous alliances, cross-licensing arrangements, or access to complementary technologies.

- protective mechanism: patents also serve as a protective mechanism in the high-tech sector, which is incredibly fast-paced and competitive. They serve to deter potential infringement allegations and legal actions brought by rivals. A company can create a protective shield with a robust patent portfolio, deterring competitors from filing lawsuits and possibly resulting in cross-licensing agreements that are advantageous to both parties.

- confidence in the potential investors: patents can provide potential investors with confidence in the value and potential of the company’s technologies, so it is easier to raise capital.

- perception of high quality: the perceived quality of an end product and the technological aspects of its components are frequently linked, especially when such features are patented. Patented technology elements frequently reflect unique solutions or improvements in a particular field. When these features are included in a product, they can help it stand out from the competition and suggest a higher degree of quality. Patented technologies are frequently associated with cutting-edge innovation, improved performance, and enhanced functionality, which can positively influence consumers' perceptions of the product's quality. Patented components or technologies may enable greater performance or enhanced functionality in the finished product. A patented technique in a smartphone camera, for example, can result in higher image quality, improved low-light performance, or advanced image stabilization. These outstanding performance attributes add to the product's perceived quality, since consumers value products that deliver excellent performance and effectively meet their needs.

- durability and reliability: patented technological elements can also add to an end product's durability and reliability. When components are patent-protected, it means they have undergone extensive research, development, and testing to assure their effectiveness and endurance. Because consumers want items that are built to last and work consistently over time, this assurance of longevity and reliability can improve the perceived quality of the product.

- better user experience: patented technology features can improve a product's overall user experience. They may provide user-friendly interfaces, seamless connectivity with other devices or platforms, or enhanced ease and usability. A product that provides a superior user experience is frequently seen as being of higher quality because it meets user expectations and makes their engagement with the product more joyful and efficient.

3.2. Corporate’s reputation through patents as reputation signals

3.3. Reputation risks from patenting

4. Business performance and CSR reporting of the high-tech companies

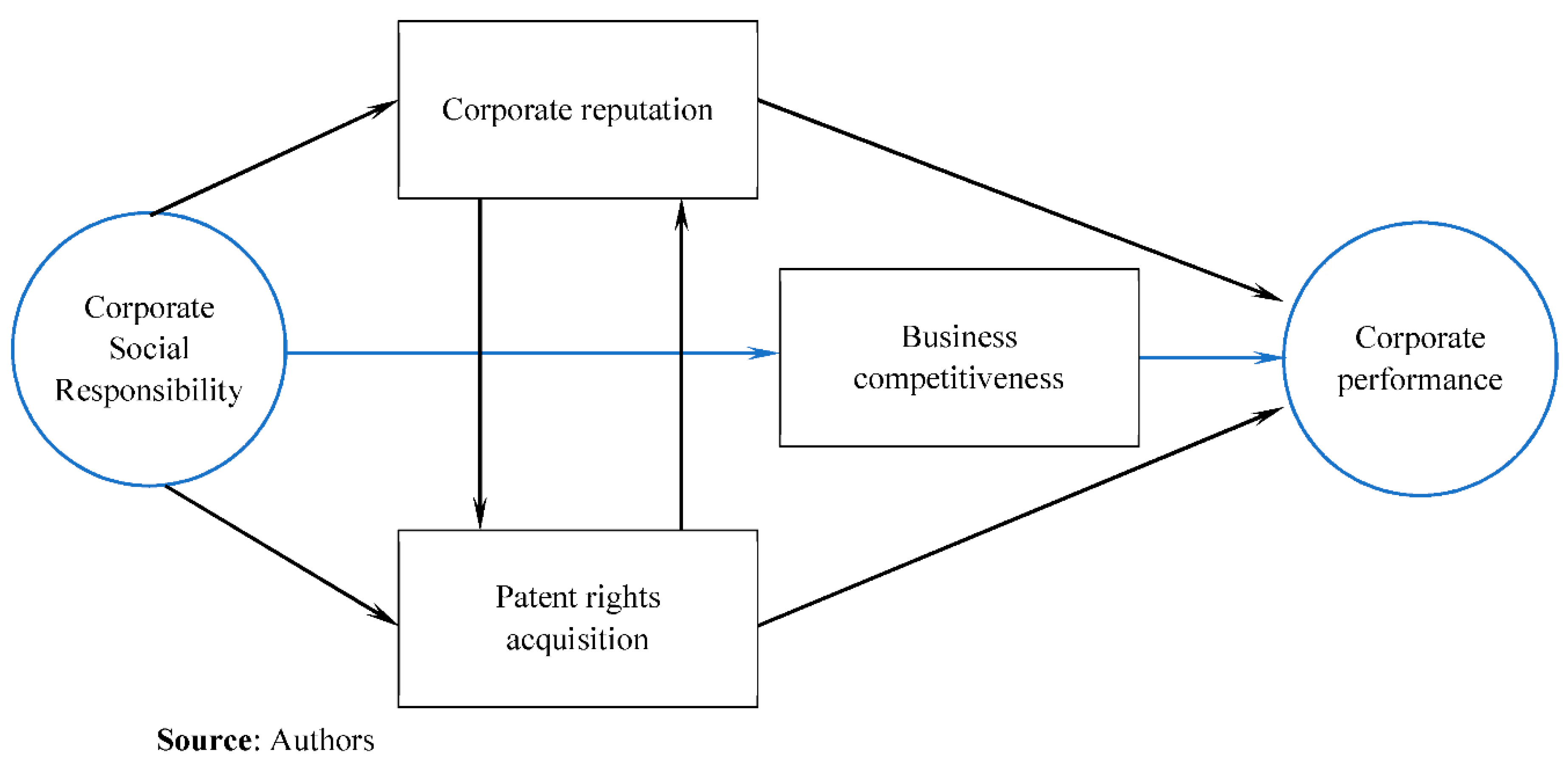

- CSR directly affects the Corporate performance and Business competitiveness (see. Bernal-Conesa, Briones-Peñalver, Nieves-Nieto, 2017, p.78). as Competitiveness mediates the relationship between the CSR strategies and performance of technological companies.

- CSR indirectly affects the Corporate performance via mediation of Corporate reputation (Mahmood and Bashir, 2020) and Corporate patenting (Barzel, 1997).

- Innovations, incl. business innovations, social innovations and ecological innovations;

- System for risk management;

- Technology development resource management and resource utilization.

- Social trust as good employer;

- Environment responsibility policy;

- Product/service quality.

- Own development of patents (as dummy variable);

- Number of patents’ acquisitions;

- The (average) innovation stage of the patents (between TRL 4 – TRL 9 stage)1

- Turnover;

- Production;

- Added value at factor costs.

5. Discussion and conclusions

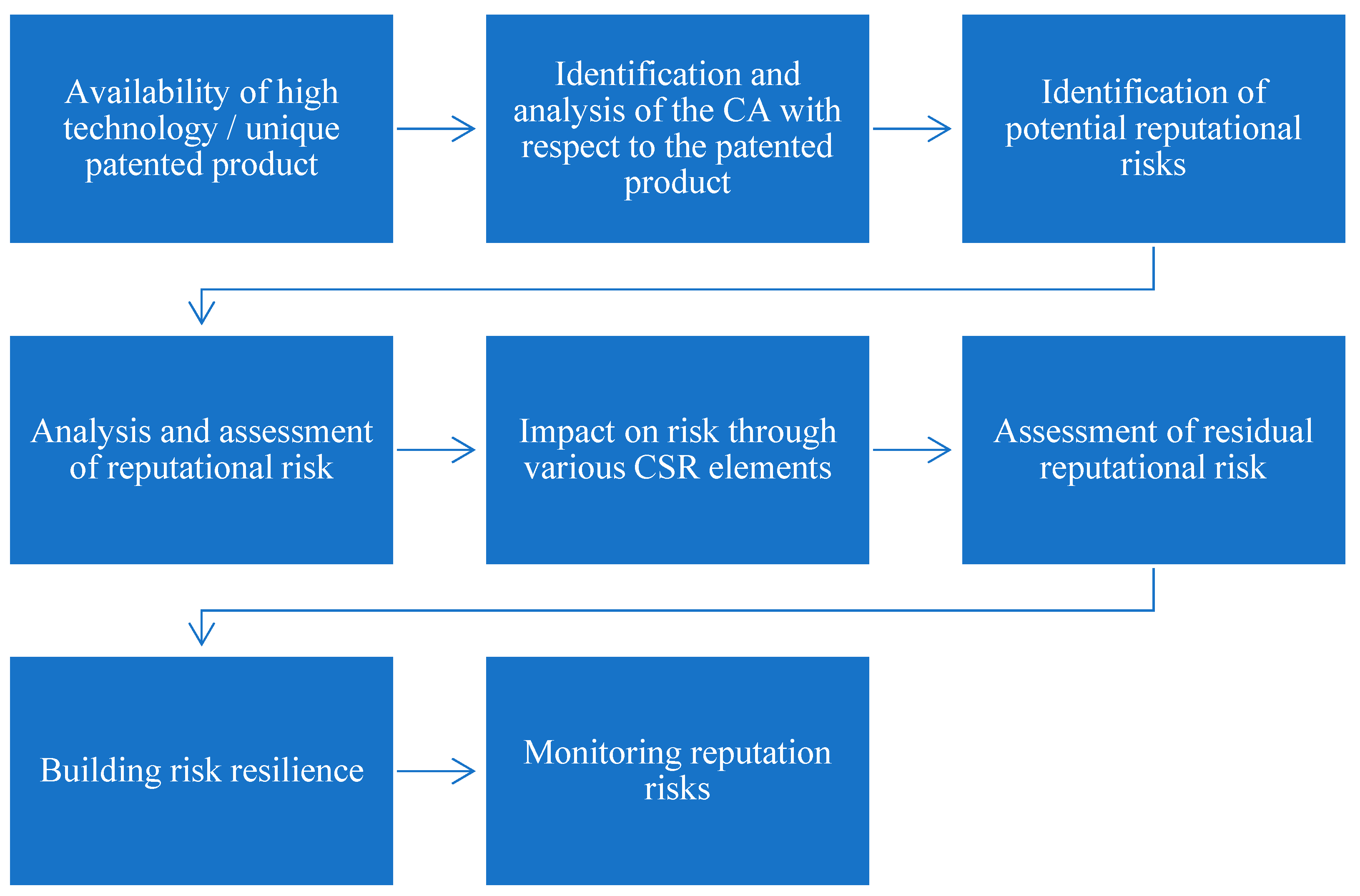

- 1)

- The availability of patentable, high-tech products. The process began when the high-tech company applied for a patent for a novel product;

- 2)

- Identifying and evaluating parties with an interest in the patented product. During this phase, it's important to identify any potential interested parties who have a direct or indirect connection to the patented technique or product and to give as much detail as you can about them. Their study should take into account a number of variables to demonstrate how the stakeholders’ expectations have changed as well as any potential threats to the high-tech company's reputation;

- 3)

- Determining any possible reputational hazards brought on by the interested parties. Reputational risk can be systematized, described, and categorised via early/preventive identification;

- 4)

- Reputational risk analysis and assessment call for a quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the risk, providing instructions for deciding on specific actions to take toward the many involved parties;

- 5)

- The effects of various CSR components on risk. Corporate social responsibility is a factor that affects how reputational risk is handled. Various social and ecological programs and/or activities have an effect on various stakeholder groups. Here, it's crucial to clarify the exact actions in light of the relevant groups. This is decided using the outcomes of the aforementioned stakeholder analysis. The corporate organization must consider the interests of the stakeholders throughout this period and prevent harm to them. The goal of the CSR risk management approach is to minimize negative effects and transform them into assets that will enhance the high-tech company's reputation;

- 6)

- An assessment of persistent reputational risk. Sometimes the threat cannot be totally eliminated, or the measures taken to do so have not been successful. This calls for more CSR effects to produce long-lasting positive trends;

- 7)

- The phase of "building sustainability" is when stakeholders link the CSR performance of the biotech company with certain social and environmental concerns. Their upkeep and expansion support the brand, uphold the image, and boost client satisfaction. It is essential to participate in active communication, conduct CSR events, and make public appearances;

- 8)

- Monitoring reputational risk – As a cyclical process, risk management calls for regular diagnosis and evaluation of all incidents that affect the firm both internally and externally. It is also necessary to conduct an ongoing review of organizational goals and any threats to those goals. During this risk management phase, the high-tech firm must take precautions to preserve the confidence of the general public and its clients and must take action to improve its reputation.

Acknowledgments

| 1 | Technology readiness levels |

References

- Asiaei, K., Bontis, N. (2019). Using a balanced scorecard to manage corporate social responsibility, Knowledge and Process Management, 26(4), 371–379. [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Sarkis, J. (2017). Improving green flexibility through advanced manufacturing technology investment: Modeling the decision process. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 188, 86–104. [CrossRef]

- Bălan D. A. (2020). Major Approaches to Measuring Corporate Reputation: An Extensive Literature Review, Revista de Științe Politice. Revue des Sciences Politiques 67/2020: pp.146-158. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1055606.

- Banjo, K.A., Aduloju, S.A., Ajemunigbohun, S.S. (2022). Environmental Risk, Reputational Risk, and Legal Risk as Determinants of the Performance of Manufacturing Companies in Nigeria. Annals of Spiru Haret University. Economic Series, 22(1), 489-502. [CrossRef]

- Barzel, Y. (1997). Economic Analysis of Property Rights. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. Print. Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions.

- Basel II Framework, ,2000, Proposed Enhancements to the Basel II Framework. Basel Committee on Banking Supervision Consultative Document. Bank for International Settlement.

- Beheshtifa, M., Korouki, A. (2013). Reputation: An Important Component of Corporations' Value, International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, Vol. 3, No. 7. [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Conesa J.A., Nieves-Nieto C., Briones-Peñalver A.J. (2016). CSR and technology companies: A study on its implementation, integration and effects on the competitiveness of companies, IC, 2016 – 12(5): 1529-1590 – Online ISSN: 1697-9818 – Print ISSN: 2014-3214. [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Conesa, Briones-Peñalver, Nieves-Nieto (2017). Impacts of the CSR strategies of technology companies on performance and competitiveness. Tourism & Management Studies, 13(4), 2017, 73-81. [CrossRef]

- Biolcheva P., Sterev N. (2023). INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS IN THE CIR--CULAR ECONOMY, VIth International Conference on Management and Strategic Decisions (ICGSM), 8-10 June 2023, Bourgas.

- Biolcheva, P. (2021). Upravlenie na Biznes Riska, UNWE, ISBN 978-619-232-524-4 (BG).

- Bocquet, R.; Le Bas, C.; Mothe, C.; Poussing, N. (2012). Are firms with different CSR profiles equally innovative? Empirical analysis with survey data, European Management Journal (2012). [CrossRef]

- Bozhinova, M., Nikolov, E. (2021), INTEGRATION OF NON-FINANCIAL REPORTING IN THE BULGARIAN MOST TRADED COMPANIES, International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference : SGEM; Sofia, Vol. 21, Iss. 5.1, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Briggs M. (2015), KFTC Recommends Fines Against Qualcomm, GLOBAL COMPETITION REVIEW (Nov. 18, 2015) http://globalcompetitionreview.com/news/article/39853/kftcrecommends-fines-against-qualcomm [https://perma.cc/9PAQ-GHLY];

- Chang, C.P. (2009). The relationships among corporate social responsibility, corporate image and economic performance of hightech industries in Taiwan. Quality and Quantity, 43(3), 417-429. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.C.; Lu, M.T.; Chen, M.J.; Huang, L.H. (2021). Evaluating the Application of CSR in the High-Tech Industry during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1715. [CrossRef]

- Circular Economy Finance Guidelines (2018), Amsterdam, circular-economy-finance-guidelines-secure-july-2018.pdf (rabobank.com).

- Creswell, J. (2013). Research design: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Demsetz, H. (1967). Toward a Theory of Property Rights. American Economic Review.

- European Commission (2014). Technology readiness levels (TRL); Extract from Part 19 - Commission Decision C(2014)4995, www.ec.europa.eu.

- European Commission (2023). Corporate social responsibility (CSR), available at: https://commission.europa.eu/business-economy-euro/doing-business-eu/corporate-social-responsibility-csr_en.

- Fombrum, C.J. (2012). The Building Blocks of Corporate Reputation: Definitions, Antecedents, Consequences. The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Reputation, Oxford University Press, 94-113. [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C., Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33(2), 233–258. [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D., Sánchez-Hernández, M. I. (2014). Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility for competitive success at a regional level. Journal of Cleaner Production, 72, 14-22. [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D., Valdez-Juárez, L., Castuera-Díaz, A. (2019), Corporate Social Responsibility as an Antecedent of Innovation, Reputation, Performance, and Competitive Success: A Multiple Mediation Analysis, Sustainability, 11, 5614. [CrossRef]

- George, J. et.al. (1999). Marketing in Technology-Intensive Markets: Toward a Conceptual Framework, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 63 (Special Issue), pp. 78-91. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh S., Sokol D. D. (2016). FRAND in India 5 (Univ. of Wis., Legal Studies Research Paper No. 1374, 2016) http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm? abstract_id=2718256&download=yes [https://perma.cc/QWU5-K5XM].

- Global Pharma Study (2023). Reputation Insights on the global pharmaceutical industry, 2023, available at https://www.groupcaliber.com/global-pharma-report-2023/.

- Grabinska, B.; Kedzior, D.;Kedzior, M., Grabinski, K. (2021). The Impact of CSR on the Capital Structure of High-Tech Companies in Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5467. [CrossRef]

- Guniganti P. (2015). KFTC Official: IP Rights Could be “a Monster”, GLOBAL COMPETITION REV. (May 19, 2015) (quoting Seong-Guen Kim, Director, International Cooperation Division, KFTC).

- Hao, J., He, F. (2022). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance and green innovation: Evidence from China, Finance Research Letters, vol.48. [CrossRef]

- He, K., Chen, W., Zhang, L. (2021). Senior management's academic experience and corporate green innovation, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol.166. [CrossRef]

- Henard, D., Dacin, P. (2010). Reputation for product innovation: Its impact on consumers. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 27(3), 321–335. [CrossRef]

- Hillenbrand, C.; Money, K. (2007). Corporate responsibility and corporate reputation: Two separate concepts or two Sides of the Same Coin?, Corporate Reputation Review 10(4):261-277. [CrossRef]

- Honey, G. (2009). A Short Guide to Reputation Risk. Gower Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-566-008995-4. рр. 38-59. [CrossRef]

- Hovenkamp, E. (2013). Predatory Patent Litigation: How Patent Assertion Entities Use Reputation to Monetize Bad Patents (August 5, 2013). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2308115. [CrossRef]

- Im, H. J., Liu J., Song, K. (2022). Does Doing Good Make Corporate Patents More Valuable? (May 24, 2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3549827. [CrossRef]

- ISO (2018). ISO 31000:2018 - Risk management — A practical guide.

- Japan Fair Trade Comm’n (2015), Guidelines for The Use of Intellectual Property Under the Antimonopoly Act Part 4(2)(iv) (2015).

- Jo, H.; Kim, H.; Park, K. (2015). Corporate environmental responsibility and firm performance in the financial services sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 257–284. [CrossRef]

- Kimmel L. (2015). Injunctive Relief for Infringement of FRAND-Assured Standard-Essential Patents: Japan and Canada Propose New Antitrust Guidance, CPI ANTITRUST CHRON., Oct. 2015, https://www.competitionpolicyinternational.com/assets/Uploads/KimmelOct-151.pdf [https://perma.cc/Z6PS-XL2Y].

- Kopeva, D., Sterev, N. and Blagoev, D. (2019). Corporate Social Responsibility in Bulgaria: Perspectives and Possibilities, Çalıyurt, KT (Ed.) New Approaches to CSR, Sustainability and Accountability, Volume I içinde (Ss. 141-158). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Mu, R., Hu, Sh., Wang, L. and Wang, S. (2018). Intellectual property protection, technological innovation and enterprise value—An empirical study on panel data of 80 advanced manufacturing SMEs. Cognitive Systems Research 52 (2018) 741-746. [CrossRef]

- Long, C. (2002). Patent Signals. The University of Chicago Law Review, 69(2), 625–679. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A., Bashir, J. (2020). How does corporate social responsibility transform brand reputation into brand equity? Economic and noneconomic perspectives of CSR, International Journal of Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Marín, L., Rubio, A., de Maya, S. R. (2012). Competitiveness as a Strategic Outcome of Corporate Social Responsibility: Competitiveness and CSR. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 19(6), 364-376. [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A., Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: a theory of the firm perspective. Acad Manag Rev. vol.26 pp. 117–127. [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, E. (2016). Global reporting Initiative and its implementation in Bulgarian and Ukrainian enterprise, Екoнoмічний вісник Дoнбасу № 4(46), 2016, UDC 657:005.34:338.24(497.2+477).

- Renfrow, J., 2023, Pharma reputation scores drop to pre-COVID levels as Haleon tops most respected, but it's a huge fall from grace for Pfizer and Moderna, available at: https://www.fiercepharma.com/marketing/pharma-reputation-scores-drop-pre-covid-levels-haleon-tops-most-respected-its-huge-fall.

- RepTrack (2022) Tech Reputation Report, available at: https://ri.reptrak.com/hubfs/_2022%20Tech%20Report/2022%20Tech%20report_X.pdf, accessed 25.06.2023.

- Reuber, A.R., Fischer, E. (2009). Signaling reputation in international online markets. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 3 (4), 369–386. [CrossRef]

- Ristuccia, H., Duchevet, M., Phaure, H. (2014). Risk Angles Reputation Risk, Deloitte, available at: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/Governance-Risk-Compliance/gx_grc_riskanglesreputationrisk.pdf.

- Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q. (2018). Environmental sustainability and production: Taking the road less travelled. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 743–759. [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374. [CrossRef]

- Stefanova, M., Petrova, V., Atanasov, A., Nikolov, E., Nikol, O., Kambourova, B. (2021), Corporate Transparency. Analytical report Bulgaria 2021, MPRA Paper No. 112363 (BG).

- Sterev, N. (2019). New Industrial Business Models: From Linear to Circular Economy Approach, Trakia Journal of Sciences, Vol. 17, Suppl. 1, pp 511-523, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sterew N., Ivanova V. (2019). From Sustainability to a Model of Circular Economy - the Example of Bulgaria, Proceedings of INTCESS 2019- 6th International Conference on Education and Social Sciences, 4-6 February 2019- Dubai, U.A.E., 150.pdf (ocerints.org).

- Suna, Y., Yanga, J., Baob, Q., Tuc, H., Lia, H. (2022). Unveiling the nexus between corporate social responsibility, industrial integration, economic growth and financial constraints under the node of firms sustainable performance, ECONOMIC RESEARCH-EKONOMSKA ISTRAŽIVANJA, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp.3788–3813. [CrossRef]

- Telford E. (2015). Is South Korea Practicing Protectionism?, THE HILL (Sept. 18, 2015) http://thehill.com/blogs/ congress-blog/foreign-policy/254045-is-south-korea-practicing-protectionism [https://perma.cc/2LJP-CZRV].

- U.S. Chamber of commerce (2014). Competing interests in china’s competition law enforcement: china’s anti-monopoly law application and the role of industrial policy 62–66 (2014) https://www.uschamber.com/sites/default/files/ aml_final_090814_final_locked.pdf [https://perma.cc/93N6-GBK8].

- U.S. Chamber of commerce (2015). Provisions on the prohibition of the abuse of intellectual property rights to eliminate or restrain competition, Art. 7 (2015), http://www.kangxin.com/en/index.php?optionid=927&auto_id=726 [https://perma.cc/C8DA-GHMD].

- Vilanova, M., Lozano, J. M., Arenas, D. (2009). Exploring the Nature of the Relationship Between CSR and Competitiveness. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(S1), 57-69. [CrossRef]

- Wæraas, A., Dahle, D. (2020), When reputation management is people management: Implications for employee voice, European Management Journal, Vol. 38, Iss, 2, pp. 277-287. [CrossRef]

| Relational Construct | Depending on the corporate's reputation, stakeholders' perspectives on it can vary. |

| Exception Attributed | A corporate’s reputation is based on the qualities that set it apart from other players in the market. |

| Perception Comparison | An corporate’s reputation is how the general public sees it. |

| Unintended Consequences | Reputation may be impacted by unanticipated events or third parties. |

| Track Record | Experience is the foundation upon which reputation is created, and with time |

| Emotional Appeal | Corporate’s reputation is based on trust |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).