Submitted:

29 June 2023

Posted:

04 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

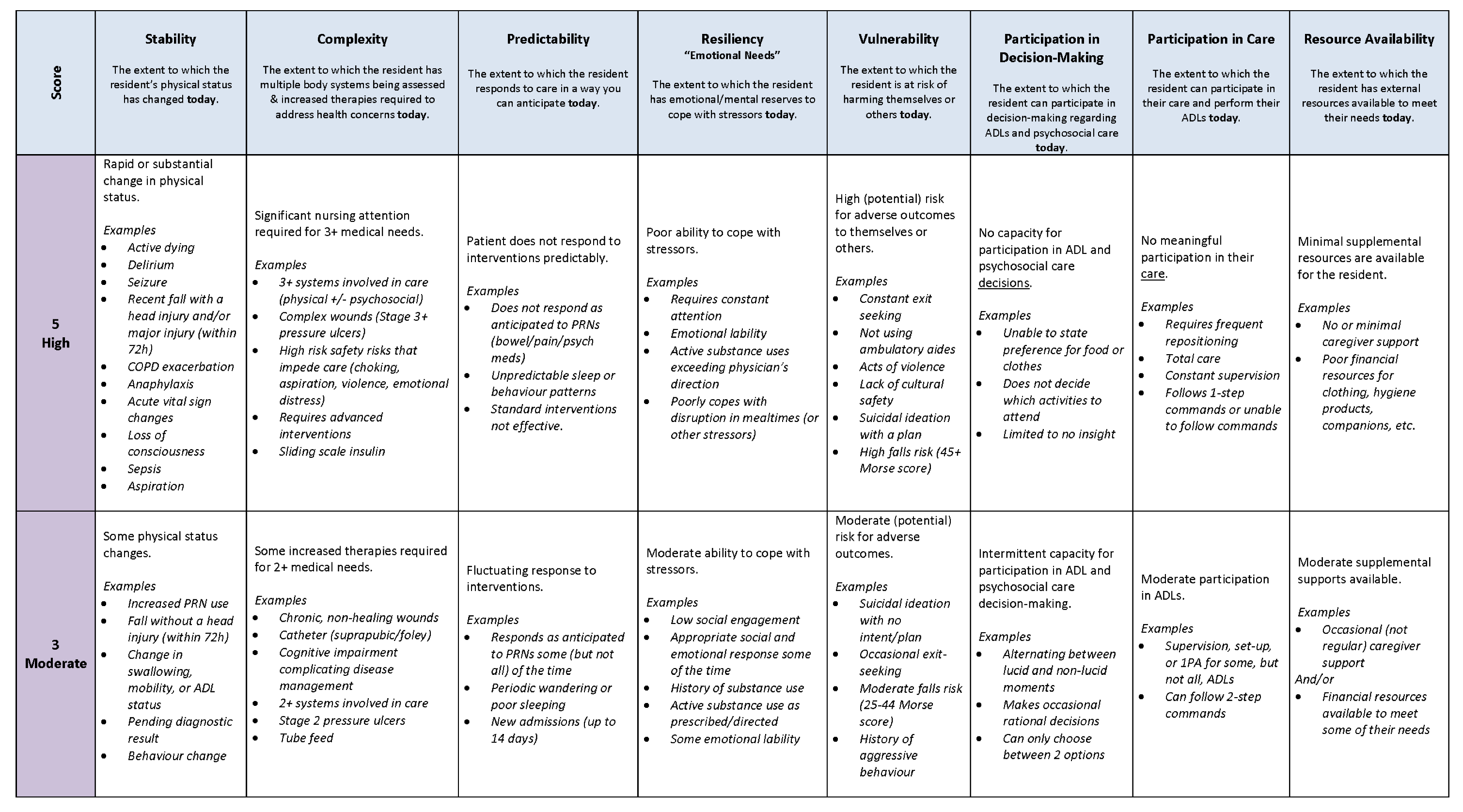

2.1. The Synergy Tool Intervention

2.2. Intervention Implementation

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Quantitative Methods

2.4.1. Sample and Data Collection

2.4.2. Data Analysis

2.5. Qualitative Methods

2.5.1. Sample and Data Collection

2.5.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Study

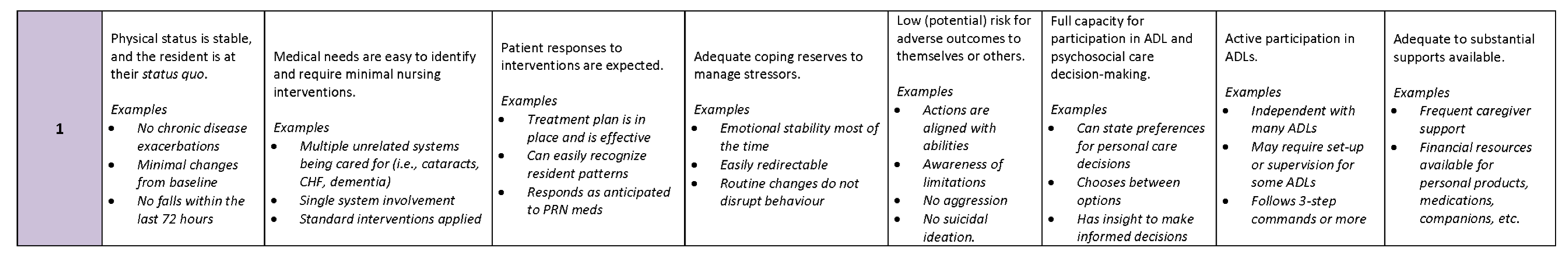

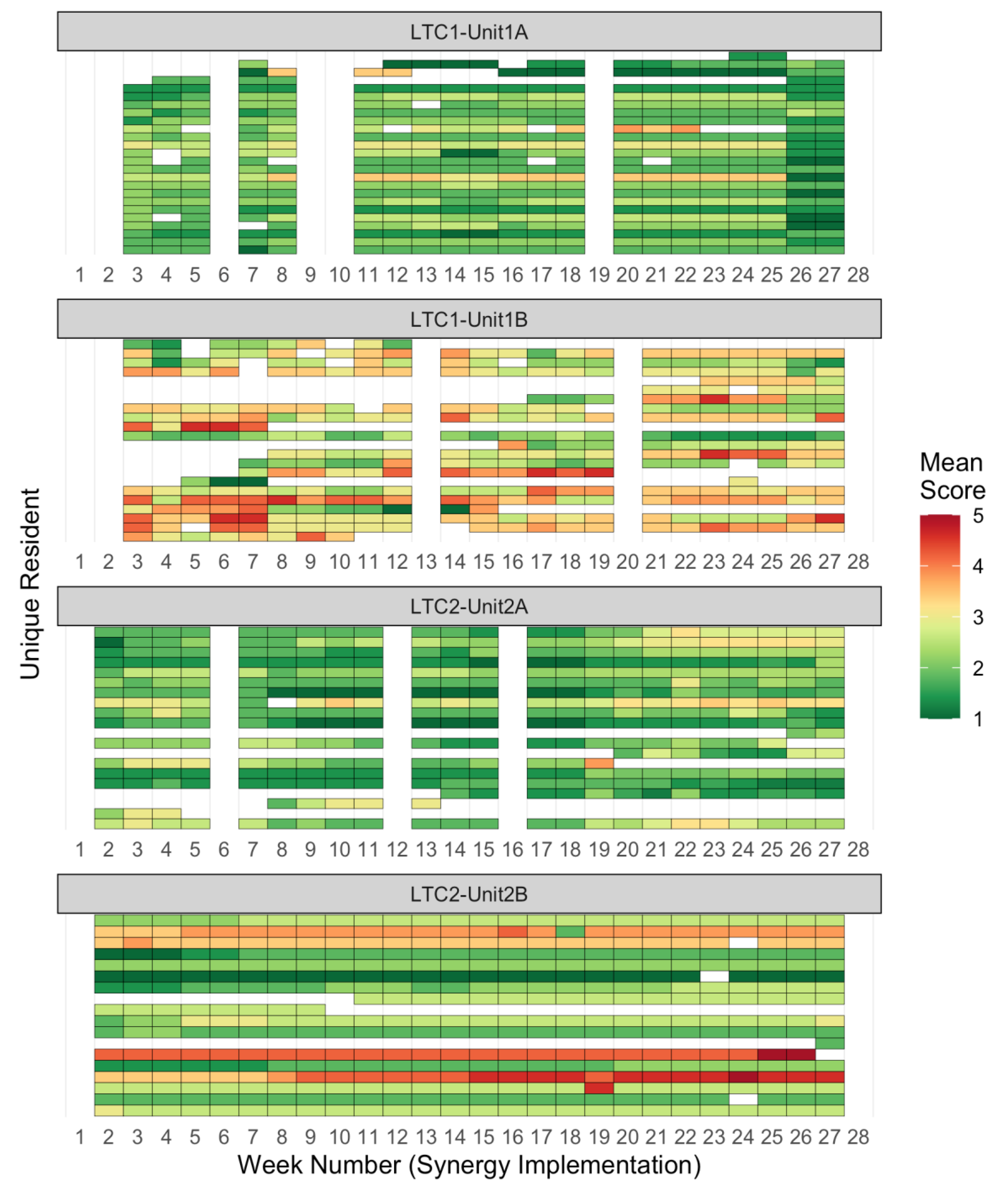

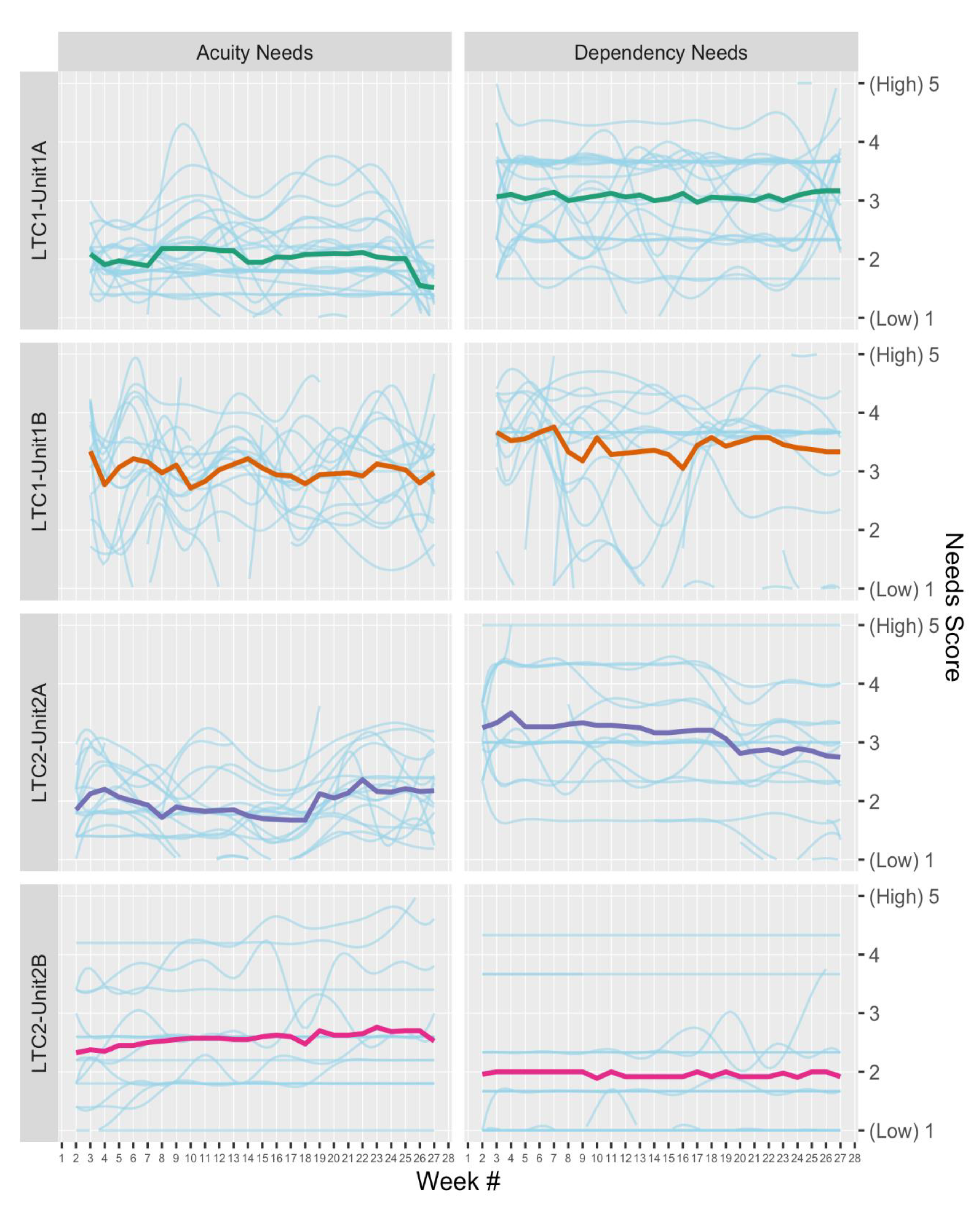

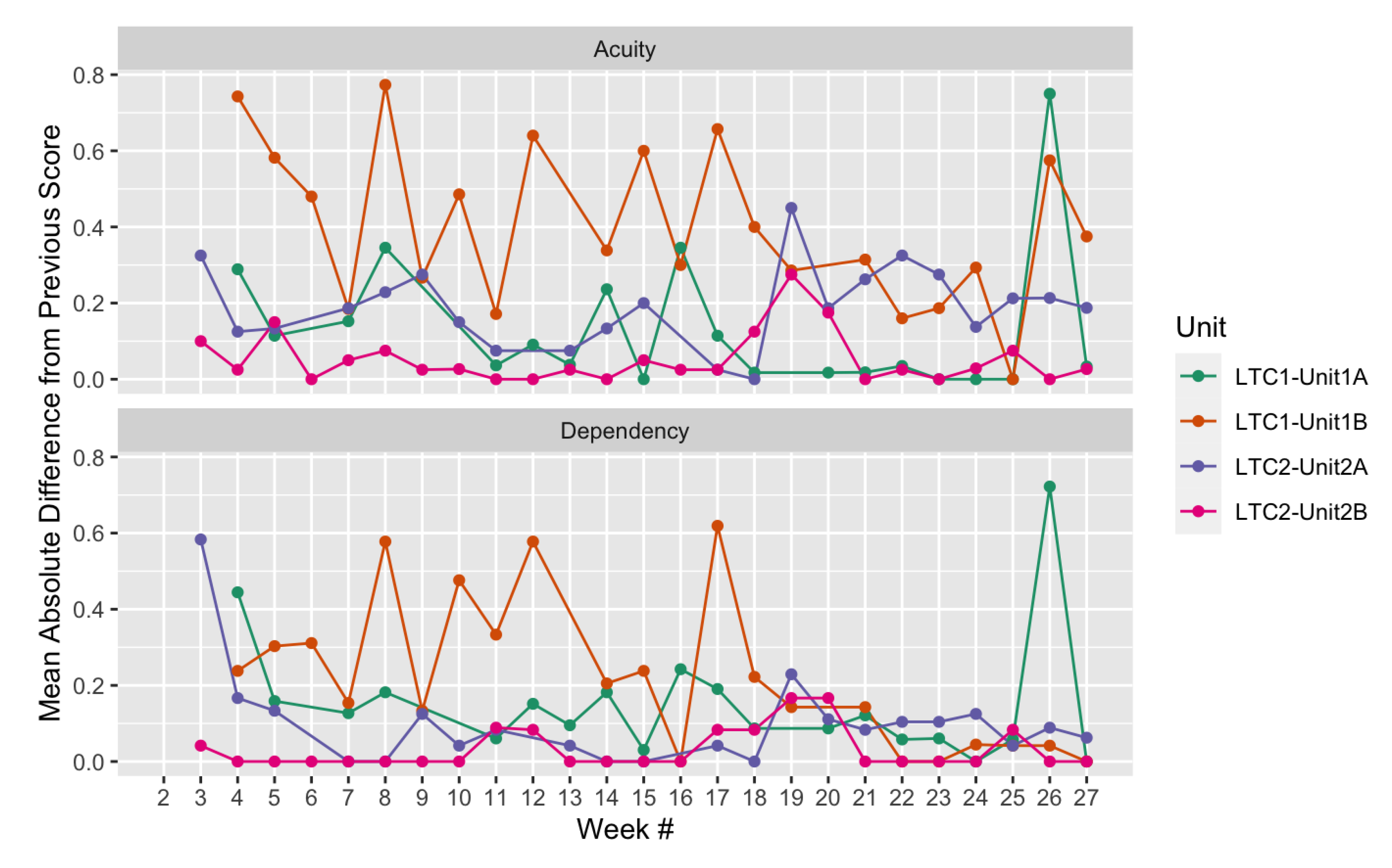

3.1.1. Synergy Scores

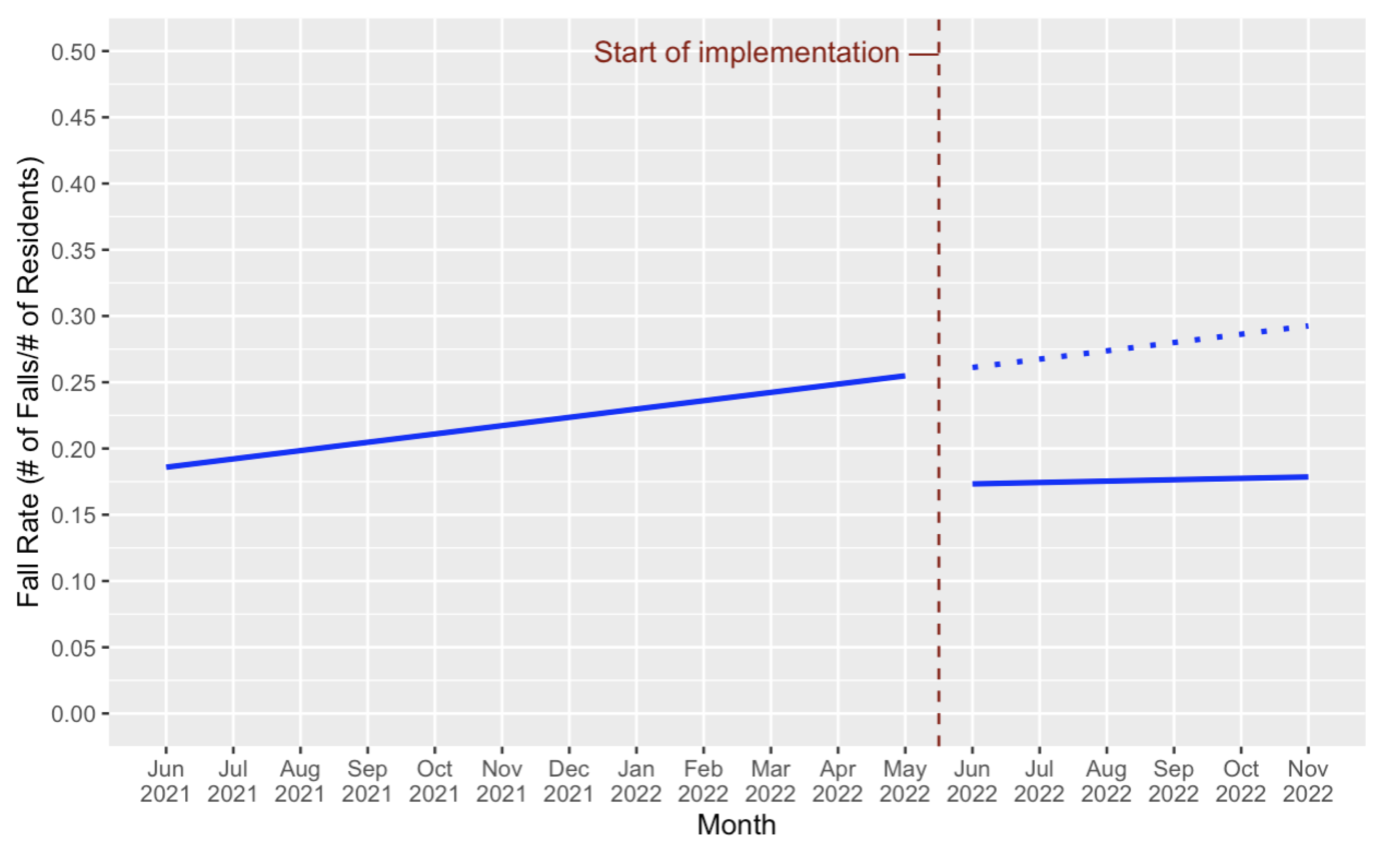

3.1.2. Administrative Resident Falls Data

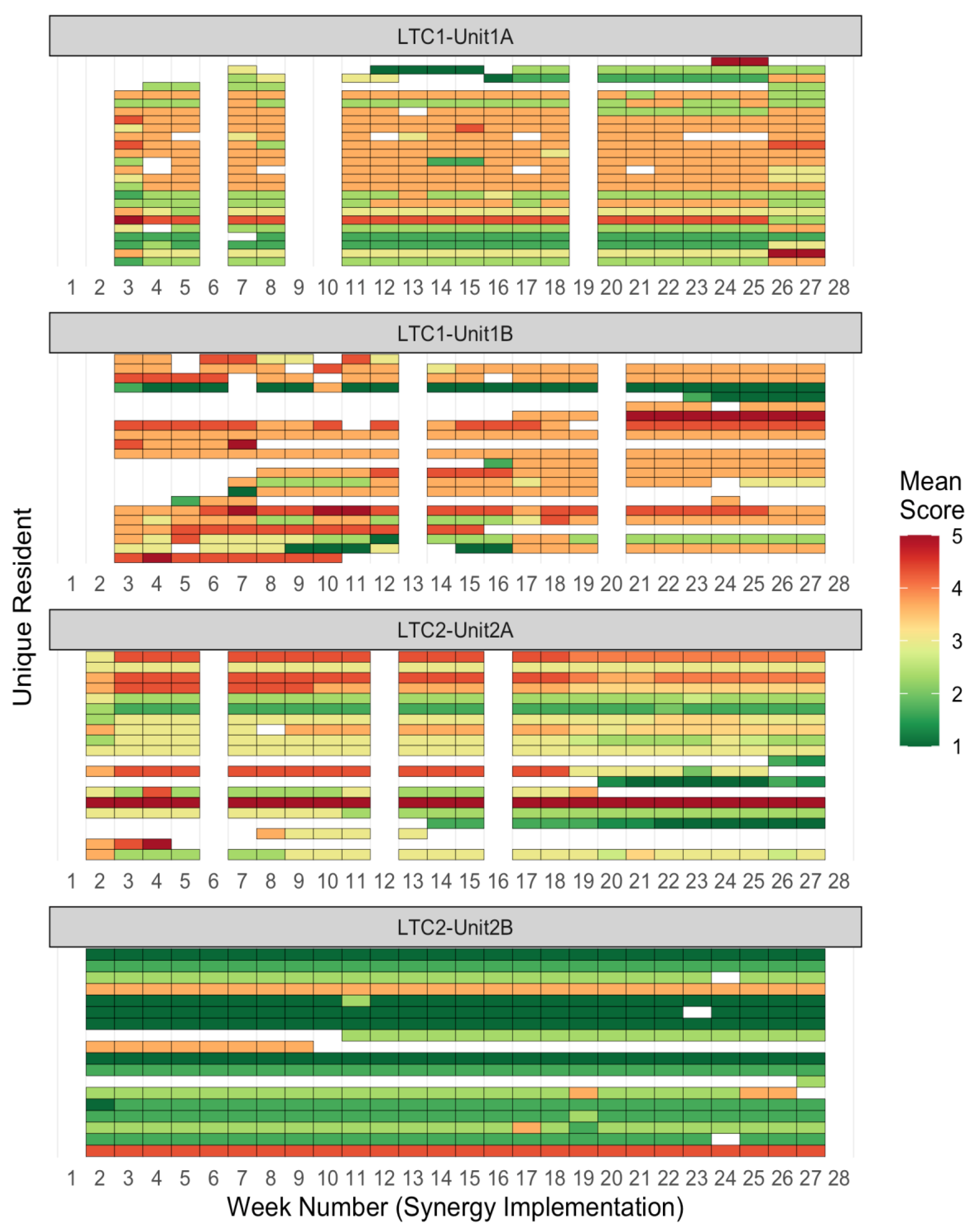

3.1.3. Economic Evaluation

3.2. Qualitative Study

3.2.1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

3.2.2. Positive Impacts Themes

3.2.2.1. Improved Care Delivery

3.2.2.2. Better Communication

3.2.2.3. Improved Resident-Family-Staff Relationships

3.2.3. Negative Structural Themes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Resident assessment tool scoring guidelines for Long-term Care

References

- Hung, L.; Yang, S.C.; Guo, E.; Sakamoto, M.; Mann, J.; Dunn, S.; Horne, N. Staff Experience of a Canadian Long-Term Care Home during a COVID-19 Outbreak: A Qualitative Study. BMC Nurs 2022, 21, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havaei, F.; Abughori, I.; Mao, Y.; Staempfli, S.; Ma, A.; MacPhee, M.; Phinney, A.; Keselman, D.; Tisdelle, L.; Galazka, D.; et al. The Impact of Pandemic Management Strategies on Staff Mental Health, Work Behaviours, and Resident Care in One Long-Term Care Facility in British Columbia: A Mixed Method Study. Journal of Long Term Care 2022, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, C.H.; Kang, S.; Eom, K.-Y.; Wee, C.W.; Song, Y.S.; Park, N.H.; Kim, J.-W.; et al. Image-Guided versus Conventional Brachytherapy for Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer: Experience of Single Institution with the Same Practitioner and Time Period. Cancer Res Treat 2023, 55, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, A.; Resnick, B.; Galik, E. The Quality of Interactions between Staff and Residents with Cognitive Impairment in Nursing Homes. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2020, 35, 153331751986325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overlap Associates PSW Perspectives on the Staffing Challenge in Long-Term Care ; 2021.

- Thirsk, L.M.; Stahlke, S.; Perry, B.; Gordon, B. #Morethanavisitor: Experiences of COVID-19 Visitor Restrictions in Canadian Long-term Care Facilities. Fam Relat 2022, 71, 1408–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, R.; Annaloro, C.; Arrigoni, C.; Ghizzardi, G.; Dellafiore, F.; Magon, A.; Maga, G.; Nania, T.; Pittella, F.; Villa, G. Burnout and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Frontline Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Published in 2020. Acta Biomed 2021, 92, e2021428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havaei, F.; MacPhee, M.; Keselman, D.; Staempfli, S. Leading a Long-Term Care Facility through the COVID-19 Crisis: Successes, Barriers and Lessons Learned. Healthc Q 2021, 23, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, J.; Chan, S.M.; Drance, E.; Globerman, J.; Hulko, W.; O’Connor, D.; Perry, J.; Stern, L.; Ho, L. Verbal and Nonverbal Indicators of Quality of Communication between Care Staff and Residents in Ethnoculturally and Linguistically Diverse Long-Term Care Settings. J Cross Cult Gerontol 2015, 30, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGilton, K.S.; Chu, C.H.; Shaw, A.C.; Wong, R.; Ploeg, J. Outcomes Related to Effective Nurse Supervision in Long-Term Care Homes: An Integrative Review. J Nurs Manag 2016, 24, 1007–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerberg, M. Appropriateness of Minimum Nurse Staffing Ratios in Nursing Homes: Report to Congress: Phase II Final: Volume I; 2001.

- Office of the Senior’s Advocate British Columbia. British Columbia Long-Term Care Facilities Quick Facts Directory: 2020 Summary Report. ; 2020;

- Ontario Long-Term Care Staffing Study Advisory Group Long-Term Care Staffing Study; 2020;

- Seetharaman, K.; Chaudhury, H.; Kary, M.; Stewart, J.; Lindsay, B.; Hudson, M. Best Practices in Dementia Care: A Review of the Grey Literature on Guidelines for Staffing and Physical Environment in Long-Term Care. Can J Aging 2022, 41, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo-Olivo, S.; Craig, R.; Corabian, P.; Guo, B.; Souri, S.; Tjosvold, L. Nursing Staff Time and Care Quality in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2020, 60, e200–e217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, N.; Cheung, H.; Hoszka, V. Briefing Report: Investigating Real Registered Nurse Staffing Levels in Ontario’s Long-Term Care Homes; 2021.

- McGregor, M.J.; Murphy, J.M.; Poss, J.W.; McGrail, K.M.; Kuramoto, L.; Huang, H.-C.; Bryan, S. 24/7 Registered Nurse Staffing Coverage in Saskatchewan Nursing Homes and Acute Hospital Use. Can J Aging 2015, 34, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poss, J.; McGrail, K.; McGregor, M.J.; Ronald, L.A. Long-Term Care Facility Ownership and Acute Hospital Service Use in British Columbia, Canada: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020, 21, 1490–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, C.; Ross, L.; Chapman, S.; Halifax, E.; Spurlock, B.; Bakerjian, D. Nurse Staffing and Coronavirus Infections in California Nursing Homes. Policy Polit Nurs Pract 2020, 21, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havaei, F.; MacPhee, M.; Ma, A.; Wong, V.W.; Li, C.; Cheung, I.; Scigliano, L.; Taylor, A. Implementation of the Synergy Tool: A Potential Intervention to Relieve Health Care Worker Burnout. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 20, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordon, C.; Lounsbury, J.; Palmer, D.; Shoemaker, C. Applying the Synergy Model to Inform the Nursing Model of Care in an Inpatient and an Ambulatory Care Setting: The Experience of Two Urban Cancer Institutions, Hamilton Health Sciences and Grand River Regional Cancer Centre. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal 2021, 31, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.I.J.; MacPhee, M.; Udod, S.; Berry, L.; Perchie, G.; Conway, A. Surveys Conducted Pre- and Post-implementation of a Synergy Tool: Giving Voice to Emergency Teams. J Nurs Manag 2021, 29, 1771–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nania, T.; Barello, S.; Caruso, R.; Graffigna, G.; Stievano, A.; Pittella, F.; Dellafiore, F. The State of the Evidence about the Synergy Model for Patient Care. Int Nurs Rev 2021, 68, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellafiore, F.; Caruso, R.; Nania, T.; Pittella, F.; Fiorini, T.; Caruso, M.P.; Zaffino, G.; Stievano, A.; Arrigoni, C. Does the Synergy Model Implementation Improve the Transition from In-Hospital to Primary Care? The Experience from an Italian Cardiac Surgery Unit, Perspectives, and Future Implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 5624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udod, S.; MacPhee, M.; Wagner, J.I.J.; Berry, L.; Perchie, G.; Conway, A. Nurse Perspectives in the Emergency Department: The Synergy Tool in Workload Management and Work Engagement. J Nurs Manag 2021, 29, 1763–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhee, M.; Wagner, J.; Udod, S.; Berry, L.; Perchie, G.; Conway, A. Using the Synergy Tool to Determine Regina Emergency Department Staffing Needs. Can J Nurs Leadersh 2020, 33, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swickard, S.; Swickard, W.; Reimer, A.; Lindell, D.; Winkelman, C. Adaptation of the AACN Synergy Model for Patient Care to Critical Care Transport. Crit Care Nurse 2014, 34, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, E.; Principi, E.; Cordon, C.; Amenudzie, Y.; Kotwa, K.; Holt, S.; MacPhee, M. The Synergy Tool: Making Important Quality Gains within One Healthcare Organization. Adm Sci 2017, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordon, C.P.; Baxter, P.; Collerman, A.; Krull, K.; Aiello, C.; Lounsbury, J.; MacPhee, M.; Udod, S.; Alvarado, K.; Dietrich, T.; et al. Implementing the Synergy Model: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Nurs Rep 2022, 12, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Saville, C.; Ball, J.; Jones, J.; Pattison, N.; Monks, T. Nursing Workload, Nurse Staffing Methodologies and Tools: A Systematic Scoping Review and Discussion. Int J Nurs Stud 2020, 103, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauskopf, J.A.; Paul, J.E.; Grant, D.M.; Stergachis, A. The Role of Cost-Consequence Analysis in Healthcare Decision-Making. Pharmacoeconomics 1998, 13, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A.M.; Wilkinson, T. Economic Evaluation of Healthcare Interventions: Old and New Directions: Table 1. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 2016, 32, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhee, M.; Havaei, F.; Fitzgerald, B.; Budz, B.; Waller, D.; Li, C.; Johannesen, D.; Larmet, J. Care Team Design: Generic; Vancouver, 2018; G: Team Design, 2018.

- Harrison, R.L.; Reilly, T.M.; Creswell, J.W. Methodological Rigor in Mixed Methods: An Application in Management Studies. J Mix Methods Res 2020, 14, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.; Friendly, M. The History of the Cluster Heat Map. Am Stat 2009, 63, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team BS: B-Spline Basis for Polynomial Splines. Available online: https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/splines/versions/3.6.2/topics/bs (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- Bradshaw, C.; Atkinson, S.; Doody, O. Employing a Qualitative Description Approach in Health Care Research. Glob Qual Nurs Res 2017, 4, 233339361774228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Sefcik, J.S.; Bradway, C. Characteristics of Qualitative Descriptive Studies: A Systematic Review. Res Nurs Health 2017, 40, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A. The Use of Triangulation in Social Sciences Research: Can Qualitative and Quantitative Methods Be Combined? Journal of Comparative Social Work 2009, 4, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual Health Res 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conference Board of Canada Sizing up the Challenge: Meeting the Demand for Long-Term Care in Canada; 2017.

- Job Bank BC Wages: Health Care Aide in British Columbia. Available online: https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/marketreport/wages-occupation/18329/BC (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Job Bank BC Wages: Licensed Practical Nurse (L.P.N.) in British Columbia . Available online: https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/marketreport/wages-occupation/4383/BC (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Job Bank BC Wages: Registered Nurse (R.N.) in British Columbia. Available online: https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/marketreport/wages-occupation/993/BC (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Tchouaket, É.; Kilpatrick, K.; Jabbour, M. Effectiveness for Introducing Nurse Practitioners in Six Long-Term Care Facilities in Québec, Canada: A Cost-Savings Analysis. Nurs Outlook 2020, 68, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada Consumer Price Index, Annual Average, Not Seasonally Adjusted Available online:. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1810000501&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.2&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2015&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2022&referencePeriods=20150101%2C20220101 (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Brownie, S.; Nancarrow, S. Effects of Person-Centered Care on Residents and Staff in Aged-Care Facilities: A Systematic Review. Clin Interv Aging 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Porock, D. Resident Outcomes of Person-Centered Care in Long-Term Care: A Narrative Review of Interventional Research. Int J Nurs Stud 2014, 51, 1395–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Frampton, S. Resident-Centered Care in 10 U.S. Nursing Homes: Residents’ Perspectives. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 2017, 49, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirdes, J.P.; Poss, J.W.; Caldarelli, H.; Fries, B.E.; Morris, J.N.; Teare, G.F.; Reidel, K.; Jutan, N. An Evaluation of Data Quality in Canada’s Continuing Care Reporting System (CCRS): Secondary Analyses of Ontario Data Submitted between 1996 and 2011. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, H.; Daly, T.J.; Choiniere, J.A. Policies and Practices: The Case of RAI-MDS in Canadian Long-Term Care Homes. Journal of Canadian Studies 2017, 50, 348–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Seniors Advocate BC Survey BC Seniors. Available online: https://surveybcseniors.org/ (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Kosse, N.M.; de Groot, M.H.; Vuillerme, N.; Hortobágyi, T.; Lamoth, C.J.C. Factors Related to the High Fall Rate in Long-Term Care Residents with Dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2015, 27, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Taylor, K.; McDaniel, Y.; Dyer, C.B. The Role of an Acute Care for the Elderly Unit in Achieving Hospital Quality Indicators While Caring for Frail Hospitalized Elders. Popul Health Manag 2012, 15, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.D.; Balatbat, C.; Corbridge, S.; Dopp, A.L.; Fried, J.; Harter, R.; Landefeld, S.; Martin, C.Y.; Opelka, F.; Sandy, L.; et al. Implementing Optimal Team-Based Care to Reduce Clinician Burnout. NAM Perspectives 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berta, W.; Laporte, A.; Deber, R.; Baumann, A.; Gamble, B. The Evolving Role of Health Care Aides in the Long-Term Care and Home and Community Care Sectors in Canada. Hum Resour Health 2013, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beeber, A.S.; Zimmerman, S.; Madeline Mitchell, C.; Reed, D. Staffing and Service Availability in Assisted Living: The Importance of Nurse Delegation Policies. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018, 66, 2158–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgeault, I.L.; Atanackovic, J.; Rashid, A.; Parpia, R. Relations between Immigrant Care Workers and Older Persons in Home and Long-Term Care. Can J Aging 2010, 29, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, A. Strategies for Overcoming Language Barriers in Healthcare. Nurs Manage 2018, 49, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cost component | Description | Estimate Breakdown | Cost Estimate |

| Training workshop | Release time for staff to participate in training, using the average of median hourly rates for care aides[42], LPNs/RPNs1 [43], and RNs[44] ($33/h), factoring in an approx. benefit of 25%, and training 4 scorers per 15-bed unit. |

$33/h × 1.25 (benefits) × 4 hours × 4 scorers/unit × 10 units |

$6600 |

| Honoraria ($100 per person) for two family/resident representatives, to provide insight for minor refinement of indicators during training |

$100/person × 2 reps. |

$200 | |

| Facilitation costs, for two expert facilitators ($60/h) |

$60/h × 4 hours × 2 facilitators |

$480 | |

| Post-workshop support | Weekly office hours held by one facilitator in the month following the workshop, to address scoring questions |

$60/h × 30 minutes/wk. × 3 weeks |

$90 |

| Scoring time | Costs for staff to score residents on a weekly basis during implementation; Synergy Tool scoring requires approximately one minute of time per resident |

$33/h × 1.25 (benefits) × 1 minute/week × 150 residents × 26 weeks |

$2681.25 |

| Total cost of six-month implementation (150-bed LTC home) | $10,051.265 | ||

| Cost per resident for a six-month implementation | $67.01 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).