1. Introduction

Uncontrolled growth of the cells manifests in malignant growth or cancer. Cancerous cells can invade other tissues and divide uncontrollably. Surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy and radiation therapy alone are in combination the main therapeutic options for this illness. The goal of radiotherapy is to deliver the highest radiation dose (tumor lethal dose-TLD) to the tumor target volume without exceeding the tolerance (tissue tolerance dose TTD) of normal healthy tissue in the vicinity of the tumor or target volume [

1]. In the last decade, the field of radiotherapy has undergone a series of developments with newer treatment delivery techniques, which enable to delivery of highly conformal, individually shaped radiation dose distributions with accuracy. This leads to a considerable reduction of radiation dose to the critical organs of the patient. Reliable and accurate quality assurance tools are required to achieve this [

2,

3]. The objective of the thesis is to design and develop a dosimetric tool (anthropomorphic heterogeneous female pelvic phantom) for PSQA of the radiotherapy process. The old dosimetric concept is based on the hypothesis that the human body is considered as a water equivalent density and interaction of radiation with a human body in the therapeutic range is of same as water. Therefore, water-equivalent phantoms have been used for routine as well as patient-specific dosimetry verifications. But the human body is not homogeneous, which consists of organs, bone, soft tissues, air etc. and their electron density is completely different to each other's. The commercially available phantoms are homogeneous which cannot represent the actual human body and also not delivered actual doses in patient treatments. So, develop an anthropomorphic heterogeneous pelvic phantom which should exactly represent the actual human body. Studies ensured that the phantom shall be constructed which is realistic in size and shape [

4,

5,

6]. It is also suitable for the assessment of accurate delivery of treatment doses and also improves dosimetry in the clinical fields. The phantom can be used in the experimental stimulation process, reducing the uncertainty during patient set-up and dosimetry instruments made in India.

Also, the high-end radiation therapy technique requires an accurate pre-treatment patient-specific quality assurance (PSQA) before the execution of patient treatment [

7,

8]. Two crucial factors must be considered in the evaluation of any radiotherapy plan or treatment procedures: a precise environment that can replicate radiation interaction with real biological tissue and a precise pre-treatment plan verification system [

9,

10]. Phantoms, which have been in use since the inspection of radiotherapy, are those substitutes that conform to the real-body scenario. Although considering that the majority of the human body consists of water, physical phantoms that are made of water or solid water equivalent materials have mostly been used for the PSQA [

11,

12]. These phantoms were used because of their cost effectiveness, universal availability, uniform density of 1 gm/cc and simpler designs. In contrast, knowing that apart from water, the human body consists of bones, soft tissues, air cavities, etc. of varied densities. Anthropomorphic phantoms now a day used in the practices of PSQA for the more pragmatic conformal and congruent representation of the human body [

13,

14] in every aspect of the anatomical variation. The objective of this research is to create a novel type of phantom and test if it accurately represents cervical cancer patients so that it may be utilized as a stand-in for patient-specific quality assurance (PSQA) in cervical cancer patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phantom Design

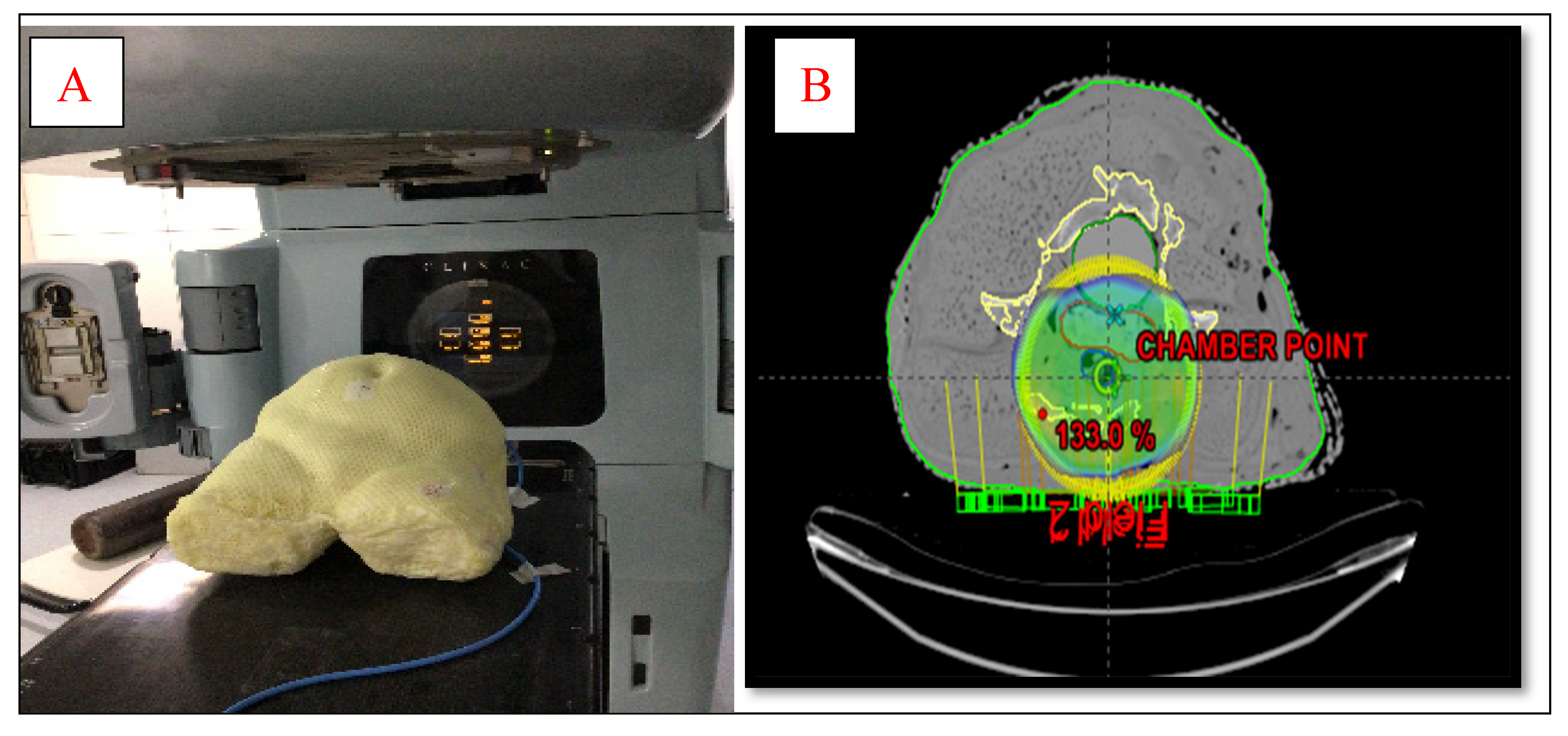

To design an anthropomorphic heterogeneous female pelvic phantom, average dimensions of pelvic regions of 50 adult female patients were taken which is shown in

Figure 1 (A). Materials used for the designing of the AHFP phantom are chosen such that it replicates the radiological characteristics of the tissues involved, which have been made of paraffin wax, water, gauge, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and polymerized siloxanes. The internal organs such as the uterus were made of polymerized siloxanes with wax, the bladder was made of a balloon filled with 250 ml water and the rectum was made of cylindrical PVC hollow pipe filled with gauge and paraffin wax. A cavity was prepared at approximately the uterus area in the phantom, and for that purpose, a 0.60cc ion chamber (PTW, Freiburg, Germany) was kept at the same position to make the cavity of dimensions equal to the ion chamber. Three reference points were created by placing the three fiducial lead markers on the two bilateral points and one anterior point on the phantom's surface in the same cross-sectional plane. To determine how accurately the finished phantom product represents a real patient, the AHFP phantom was scanned with a CT scanner (Toshiba Alexion 16 multi-slice CT scanner) at120 kVp and250 mAs, and a slice thickness of 2 mm. The CT images were transferred to the Eclipse treatment planning system (version 11.0.31) (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, USA). The CT images of the phantom were compared to CT images of randomly selected cervical cancer patients with similar scanning parameters (120kVp, 250mAs, and 2 mm slice thickness).

Table 1. Shows the mean and standard deviation of the CT number in Hounsfield units (HU) for

patient and phantom CT images. The relative electron density of the materials was calculated by

given formulas in (i) & (ii); (Thomas, 2014) [15].

| Pe = HU/1000+1 HU< 100 |

(1) |

| Pe = HU/1950+1 HU≥ 100 |

(2) |

where pe is the relative electron density of the materials.

2.2. Phantom Validation

Patient-specific absolute dosimetry

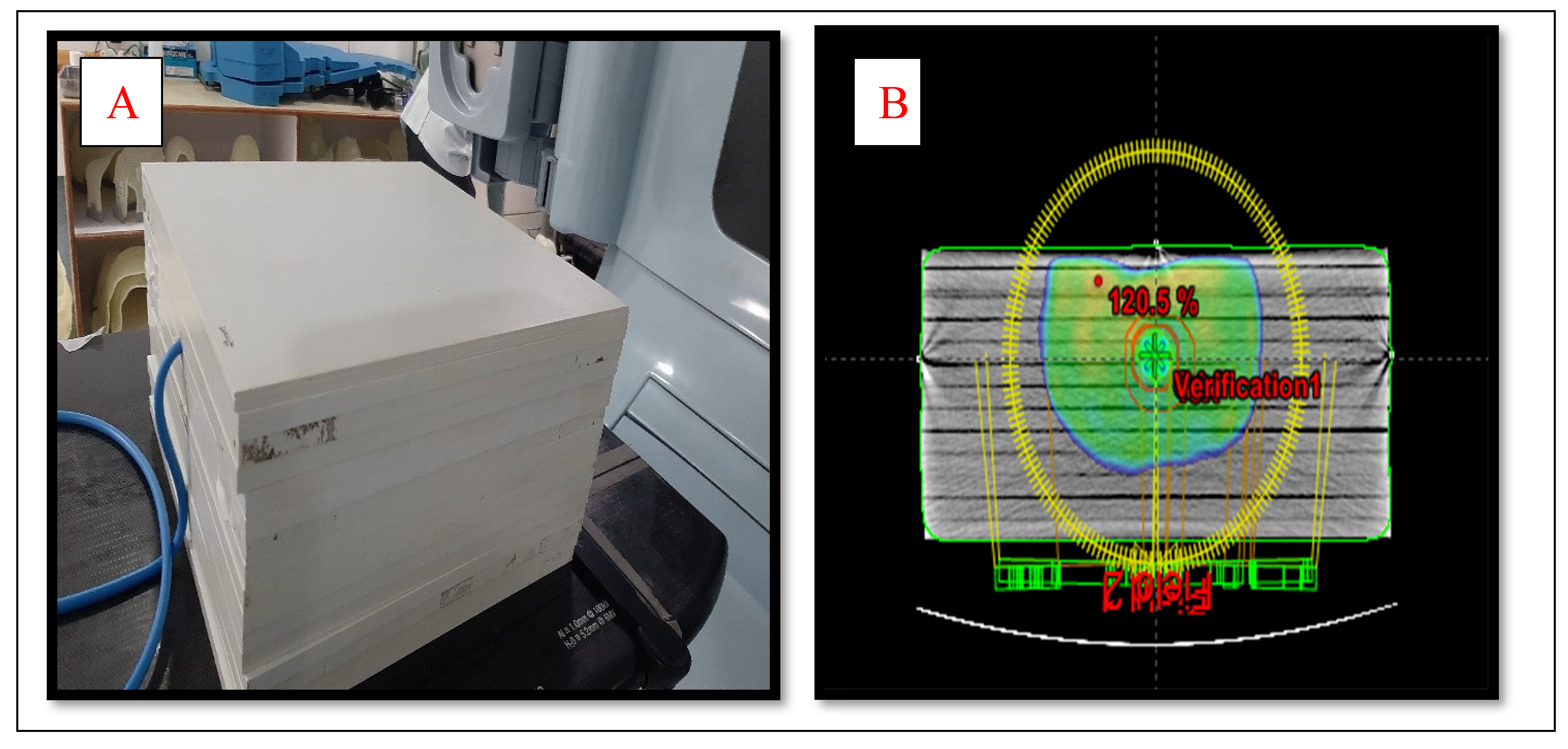

Two kinds of phantoms were chosen for the patient-specific absolute dosimetry of the completed RapidArc treatment plans. The first one was a homogeneous " Water–equivalent RW3 solid phantom"(PTW Freiburg¸ Freiburg¸ Germany)as shown in

Figure 2(A)¸ each slab of which was made of polystyrene with the effective atomic number 5.74. The second phantom was the AHFP phantom as shown in

Figure 1(A). The density of the internal organs of this AHFP phantom was equivalent to that of the human pelvis. The CT of phantoms was done on a Toshiba Alexion 16 multi-slice CT scanner with a slice thickness of 2 mm for planning purposes. The CT images were imported on Eclipse (version 11.0.31) TPS (Varian Medical Systems¸ Palo Alto, USA) and RapidArc plans already done for patient treatment were exported on both phantoms which are seen in

Figure 1(B) & 2 (B).

Thirty cervical cancer patients who underwent RapidArc therapy were chosen, ranging in age from 37 to 70 (Average 53.5) years were selected randomly for the study. Dual arcs were used for all the RapidArc plans. Since dual arc can improve PTV coverage, enhance the modulation factor during optimization, and spare the OARs compared to single arc. The first arc was clockwise rotation with a gantry angle of 181° to 179° and a collimation angle of 30°. The second arc had a collimation angle of 330° and an anticlockwise rotation with gantry angles of 179° to 181°. All the selected plans were done with 6MV photon beam¸ and field arrangement was done in such a way that all fields were coplanar with couch angle 0°. A Dose volume optimizer (DVO) was used for plan optimization and an anisotropic analytical algorithm (AAA) version 11.30.1 with a grid size of 0.25 cm was used for dose calculation. All the plans were delivered and the dose for each plan was measured using a PTW UNIDOSE electrometer connected with a 0.6cc ionization chamber (IBA Dosimetry Germany), which was fixed in phantoms.

The percentage (%) variation between the measured dose on linear accelerator and the planned dose on TPS was calculated by the following formula; Percentage of variation = (measured dose at Linac – TPS planned dose)/ TPS planneddose×100

The planned dose on TPS and measured dose from the machine of Slab Phantom and AHFP phantom were compared and represented in

Table 1 and

Table 2 respectively.

3. Results

Overall, there is good agreement between the measured CT number (HU) and relative electron density (RED) of the AHFP phantom and the patient groups. Table (1) displays the findings of the comparison between measured CT numbers from a sample of patients from our institution who were selected at random and the CT numbers of the phantom. Hence it was observed that AHFP fabricated for this study matched both the qualitative and quantitate aspects of the CT evaluation.

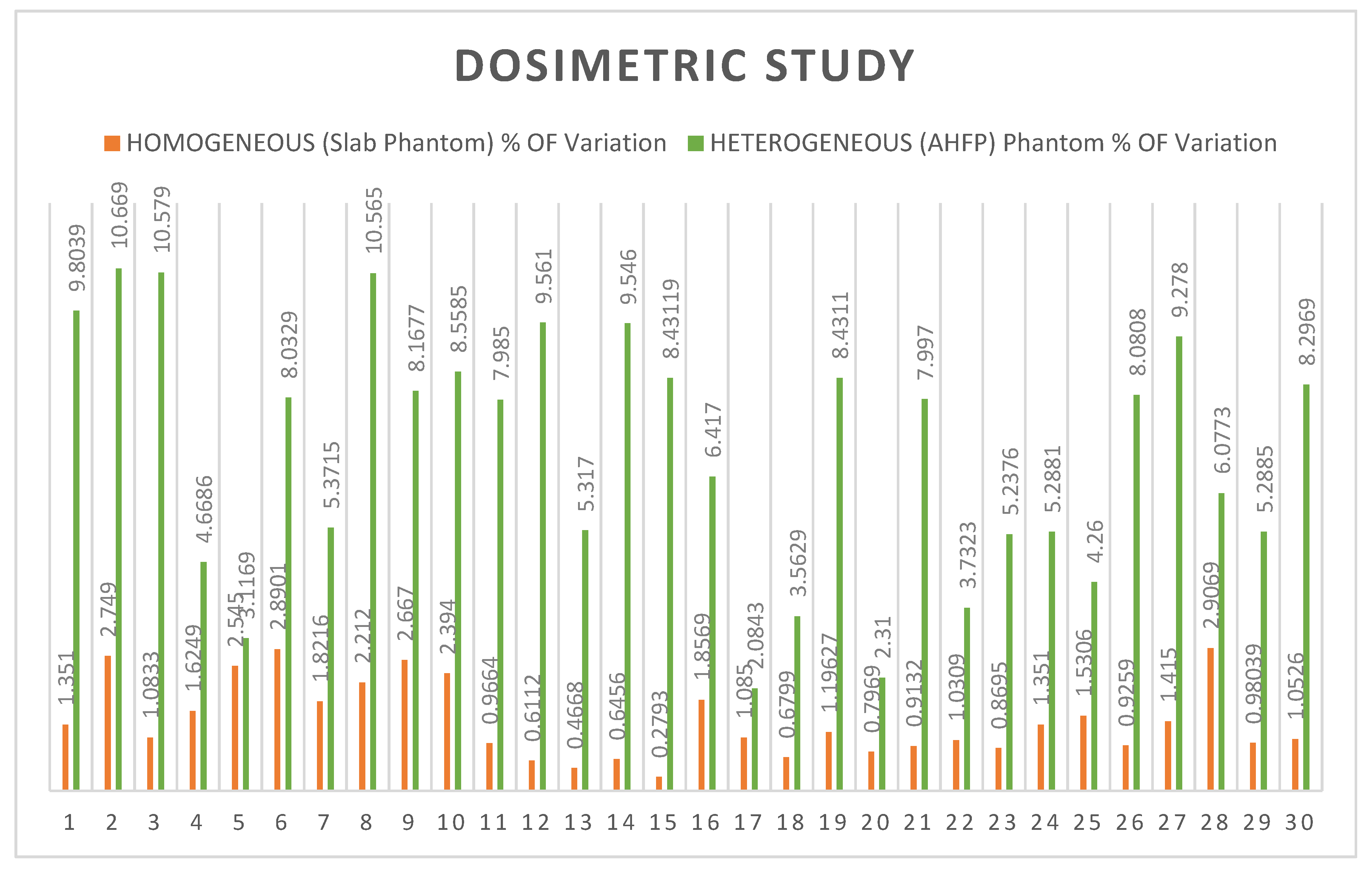

In the case of slab phantom, the mean percentage variations between planned and measured doses of all rapid arc QA plans were as 1.4299 and standard deviation 0.768 (t=0.00508, ρ= 0.497982) The result is not significant at p < .05 and shown in

Table 2. For the AHFP phantom, the mean percentage variations between planned and measured doses of all rapid arc QA plans were 6.890 and the standard deviation was 2.565 (t= 3.21604, ρ= 0.001063 <0.05), the outcome is significant and shown in

Table 3. The comparative study of the percentage of variation between homogeneous slab phantom and AHFP phantom is given in

Table 3. The t-value is -11.17016 and the p-value is < .00001. The result is significant at p < .05 and their graphical representation is shown in

Figure 3.

4. Discussion

During the research, it was discovered that the HU (CT number) and relative electron density values of our locally manufactured AHFP phantom are quite similar to those of a human female pelvis, which is tabulated in

Table 1. A variety of techniques have been created to compare sets of planned and measured radiation dose distributions in radiotherapy dosimetry. Here, we compare the homogeneous slab phantom and AHFP phantom's measured dose on Linac (Clinac iX medical linear accelerator Varian Medical System, Palo Alto, USA) and planned dose on eclipse planning system (Version 11.0.31) (Varian Medical System, Palo Alto, USA). In the case of homogenous slab phantom, there is less than a 3% difference in percentage between planned and measured doses with a standard deviation of 0.7682 (t=0.00508, p= .497982. The result is not significant at p< 0.05). The deviations of planned and measured value of dose in the AHFP phantom were found as 10.67% (maximum value), 2.31% (minimum value) and 6.89% (average value) with standard deviation 2.565 (t=3.21604, p=0.001063). The result is significant at p<0.05). Also, the percentage of variation between homogeneous slab phantoms with AHFP phantom, the t-value is -11.17016. The p-value is < .00001. The result is significant at p<0.05. We can see that the outcomes differ significantly due to the influence of heterogeneous media in

Figure 3.

The human body is made up of various densities, such as fat, bones, air cavities, and tissue. The amount of radiation dose deposited at the interface of two mediums varies significantly due to the difference in electron densities of the two media. Because bones have a larger density than soft tissue, they produce more secondary electrons [

17,

18]. As a result, the dosage at the bone-soft tissue interface is higher. A similar phenomenon occurs at the interface of all two metals with different densities. Heterogeneity is one of the hardest problems that dose calculation algorithms must solve. The TPS currently use newer and more precise algorithms that, like AAA, apply the heterogeneity adjustment factor when calculating dose [

19,

20,

21,

22]. The patient-specific absolute dosimetry should be carried out using a heterogeneous phantom that mimics the density of the human body to confirm the correctness of the dose computed by these algorithms in the instance of each patient. (O. Gurjar et al., 2014) study on radiation dosimetry for a contemporary radiotherapy approach employing a real tissue phantom [

23]. With IMRT (head phantom) and IMRT (tissue phantom), the mean percentage deviation between planned and measured doses were found to be 2.36 (SD: 0.77), and 3.31 (SD: 0.78) correspondingly. Although the percentage variation in the case of the head phantom was within the tolerance limit (3%), it was nonetheless larger than the outcomes obtained utilizing phantoms that were readily available in the marketplace [

24,

25,

26,

27]. And the majority of tissue phantom cases had percentage variations that exceeded the tolerance level.

5. Conclusion

This study concludes that the materials and design of the phantom were found to be appropriate for the advanced radiotherapy dosimetry study; the phantom was simple to use, and there were no problems with transportation. AHFP phantom results were found to have higher dose variability thenthe slab homogeneous phantom. The algorithm AAA does not calculate doses in the heterogeneous medium as accurately as it calculates in the homogeneous medium. Therefore, patient-specific absolute dosimetry should be performed using a heterogeneous phantom that closely resembles the actual human body in terms of both density and design.

Funding

The authors declare that, this study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- FM Khan, The Physics of Radiation Therapy, fourth ed., Philadelphia, Wolters Kluwer, 2012.

- American Association of Physicists in Medicine Radiation Therapy Committee Task Group 53, Quality assurance for clinical radiotherapy treatment planning, Med. Phys. 25, (1998) 1773–1829.

- American Association of Physicists in Medicine Radiation Therapy Committee Task Group 40, Comprehensive QA for Radiation Oncology, Report of the AAPM Radiation Therapy Committee Task Group 40, Med.Phys.21, (1994) 581–618.

- Absorbed dose determination in external beam radiotherapy: An international code of practice for dosimetry based on absorbed dose to water. IAEA¸ Vienna¸ 2000.

- The ICRU Report 83, prescribing, recording, and reporting photon beam intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), Cancer/Radiotherapy, (2011)15(6-7), 555–559.

- International Commission on Radiation Units and measurements ICRU), Tissue substitutes in radiation dosimetry and measurement. Report No. 44. Bethesda, MD, USA, (1998).

- Bagdare P, Dubey S, Ghosh SK, et al. Analysis of gamma index using in-house developed heterogeneous thorax phantom. Int J Radiol RadiatTher. 2021; 8(1):9-11.

- Svenesson, GK. Quality assurance in radiation therapy: physical effort. IntJRadiatOncolBiolPhys.1984; 0(1):23-29.

- Brahme A, Chavaudra J, Landberg T, et al. Accuracy requirements and quality assurance of external beam therapy with photons and electrons.ActaOncol.1988;1(1):1-76.

- Manikandan A, Sekaran SC, Sarkar B, et al. A homogeneous water-equivalent anthropomorphic phantom for dosimetric verification of radiotherapy plans.JMedPhys.2018; 43(2):100–105.

- Letourneau D, Publicover J, Kozelka J, et al. Novel dosimetric phantom for quality assurance of volumetric modulated arc therapy Med Phys.2009;36(5):1813–1821.

- Gurjar OP, Mishra SP. A comparative study on patient–specific absolute dosimetry using slab phantom, acrylic body phantom, and goat headphantom.IntJCancerTherOncol.2015; 3(2):1–5.

- Yasui K, Toshito T, Omachi C, et al. Dosimetric verificationof IMPTusing a commercial heterogeneous phantom. J ApplClin Med Phys.2019; 20(2):114–120.

- Chen MW, Deng XW, Huang SM, et al. Application ofamorphoussilicon electronic portal imaging device (a–SiEPID) to dosimetry qualityassuranceofradiationtherapy.AiZheng.2007;26(11):1272–1275.

- Thomas, S. J. (2014). Relative electron density calibration of CT scanners for radiotherapy treatment planning. 72(AUG.), 781–786.

- Litzenberg, D. W. , Amro, H., Prisciandaro, J. I., Acosta, E., Gallagher, I., & Roberts, D. A. (2011). Dosimetric impact of density variations in Solid Water 457 water-equivalent slabs. Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics, 12(3), 231–247.

- Nakao, M. , Ozawa, S., Miura, H., Yamada, K., Habara, K., Hayata, M., Kusaba, H., Kawahara, D., Miki, K., Nakashima, T., Ochi, Y., Tsuda, S., Seido, M., Morimoto, Y., Kawakubo, A., Nozaki, H., & Nagata, Y. (2020). Development of a CT number calibration audit phantom in photon radiation therapy: A pilot study. Medical Physics, 47(4), 1509–1522.

- Schaly, B. , Varchena, V., Au, P., & Pang, G. (2009). Evaluation of an anthropomorphic male pelvic phantom for image-guided radiotherapy. Reports in Medical Imaging, 2, 69–78.

- Shrotriya, D. , Yadav, R. S., Srivastava, R. N. L., & Verma, T. R. (2018). Design and development of an indigenous in-house tissue-equivalent female pelvic phantom for radiological dosimetric applications. Iranian Journal of Medical Physics, 15(3), 200–205.

- Singh, S., Raina, P., & Gurjar, O. P. (2020). Dosimetric Study of an Indigenous and Heterogeneous Pelvic Phantom for Radiotherapy Quality Assurance. Iranian Journal of Medical Physics, 17(2), 120–125. 2.

- Singh, V. P. , & Badiger, N. (2014). Effective atomic numbers of some tissue substitutes by different methods: A comparative study. Journal of Medical Physics, 39(1), 24.

- Srivastava, R. P. , & De Wagter, C. (2019). Clinical experience using Delta 4 phantom for pretreatment patient-specific quality assurance in modern radiotherapy. Journal of Radiotherapy in Practice, 18(2), 210–214.

- Gurjar, O., Mishra, S., Bhandari, V., Pathak, P., Patel, P., & Shrivastav, G. (2014). Radiation dose verification using real tissue phantom in modern radiotherapy techniques. Journal of Medical Physics, 39(1), 44.

- Yasui, K., Toshito, T., Omachi, C., Hayashi, K., Kinou, H., Katsurada, M., Hayashi, N., & Ogino, H. (2019). Dosimetric verification of IMPT using a commercial heterogeneous phantom. Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics, 20(2), 114–120.

- Zain, N. E. M., Jais, U., Abdullah, R., Abdullah, R., & Rahman, W. N. W. A. (2019). Dosimetric Characterization of Customized PLA Phantom for Radiotherapy. Jurnal Sains Nuklear Malaysia, 31(2), 1–6.

- Zhang, F., Zhang, H., Zhao, H., He, Z., Shi, L., He, Y., Ju, N., Rong, Y., &Qiu, J. (2019). Design and fabrication of a personalized anthropomorphic phantom using 3D printing and tissue equivalent materials. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery, 9(1), 9400–9100.

- HillR, Kuncic Z, Baldock C. The water equivalence of solid phantoms for low energy photon beams. MedPhys. 2010; 37(8):4355–4363.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).