1. Introduction

To promote public health, the quality of care and patient safety, it is essential for healthcare systems to have the capacity to exhibit resilient performance in both everyday practice and major crises, such as a pandemic. Operationalizing resilience in complex healthcare systems has been on the global agenda for decades. However, the elucidation of ways of improving the prerequisites for resilient performance is still a work in progress [

1,

2]. From a complexity perspective, the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) had a tremendous impact on societies and stress-tested the resilience of healthcare systems [

1,

3].

To provide care for the surge of patients suffering from a contagious disease that in many cases required critical care, healthcare organizations, teams and individuals struggled with their initially limited knowledge of the disease and insufficient human and material resources [

4,

5]. To adapt and develop the required capacity, intensive care units (ICUs) in particular were forced to extreme escalation of beds [

6,

7]. Understanding the response of intensive care to the surge that occurred during the pandemic can provide insights that can be used to design strategies to enhance resilient performance in healthcare.

Resilience requires the ‘potentials’ for resilient performance to exist within the system, i.e., the capacity to act in specific ways under certain conditions [

8]. Resilience in healthcare can be defined as ‘the capacity to adapt to challenges and changes at different levels of the system to maintain high-quality care’ [

2], a definition which also supports our understanding of resilience as a phenomenon. The healthcare context is a complex adaptive system (CAS), and as such, it constantly interacts with the environment and includes many different actors and interacting systems at different levels [

9]. One characteristic of a CAS is its self-organizing nature, which, due to its flexibility and adaptability, enables the system to remain stable despite challenges. However, changing dynamics and disruptions also have the potential to destabilize the system [

10,

11,

12]. Individuals and teams within a CAS perceive, act, react, communicate, adapt, learn and self-organize over time [

10]. The microlevel, such as that of a care department, sometimes operates at different temporalities than the mesolevel (such as a healthcare organization) or the macrolevel (i.e., national and international society), thus raising challenges for the ability to anticipate and understand a larger view of the system [

8].

Healthcare is characterized by the tensions between demand and capacity and between work-as-imagined and work-as-done [

13]. Different types of adaptation to overcome misalignments are performed at different temporal and spatial scales [

13,

14], e.g., at different levels of the system and at different times. However, such adaptations are not normative, as their outcome can be both positive and negative and can vary across the system and across time [

13]. Adaptive behaviors can be expedient locally in the short term but produce complex and unintended outcomes elsewhere and at a later point [

15,

16]. Expedient adaptations are dependent on the adaptive capacity of the organization, but the individual´s adaptations in the context of daily work are not always equivalent to building adaptive capacity within the system itself [

16,

17]. To understand how adaptations can support resilient performance at the micro-meso-macrolevels, the complexity of the healthcare system must be considered [

9,

16].

Intensive care is a complex technology and resource-intense operation that requires high staff density as well as specialist competencies ranging across several professions [

18,

19]. Prepandemic ICU capacity, the pandemic surge response and the outcomes of intensive care patients varied widely across countries and regions [

5,

6,

7]. Internationally, during the pandemic, deficits in staff and material resources as well as a higher variation in standards of care delivery in the ICU were reported [

5,

6,

19]. In Sweden, overall ICU capacity more than doubled during the first wave of the pandemic [

7], and some regions witnessed up to a fivefold increase [

20]; in addition, Sweden reported lower mortality rates than many other countries [

7]. However, staff reported a strained situation [

21], patients were exposed to adverse events [

22], and the effects of the pandemic are still being explored. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a plethora of publications regarding

what was done to meet the surge of critically ill patients. However, given the extreme strain to which ICUs were exposed, our understanding of

how the escalating process occurred is still insufficiently detailed. To prepare healthcare more effectively for both future crises and standard situations, further understanding of resilient performance in ICUs is necessary [

5,

23].

Resilient performance requires the potential to anticipate, monitor, respond and learn [

8]. In terms of surge capacity in times of a mass event, such as a pandemic or other disasters, resilience is largely related to the prerequisites for the adaptive capacity of various system components, which are commonly referred to as the four Ss (

space, stuff, staff and

system) [

23,

24]. Reflecting on the need for knowledge during the current pandemic, Salluh et al. [

23] suggested adding a fifth S to represent

science. However, resilient healthcare is an emerging research area and to improve our understanding of this topic and promote theoretical development in this field, a contextual understanding based on empirical data is necessary [

25,

26,

27]. A dynamic situation such as the pandemic [

3], highlights the need for a resilient healthcare system [

1]. As our knowledge of how adaptive capacity can be unfolded in practice exhibits certain gaps, exploration of the underlying dynamics of work-as-done that were operative during the pandemic is of interest and importance for both academics and the healthcare community [

2]. Given the unprecedented escalation in capacity, intensive care during the pandemic provides an excellent study context to explore how healthcare, as a CAS, managed the escalation process based on resilient performance at different levels of the system.

The main aim of this study was to explain the escalation process of intensive care during the first wave of the pandemic from a microlevel perspective, including expressions of resilient performance, intervening conditions at the micro-meso-macrolevels and short- and long-term consequences. A secondary aim was to provide clinical recommendations for the different levels of the system regarding how to optimize the prerequisites for resilient performance in intensive care. This research is expected to contribute to the tasks of operationalizing resilience and enhancing resilient performance in both standard situations and future crises in ICUs and other healthcare settings.

3. Results

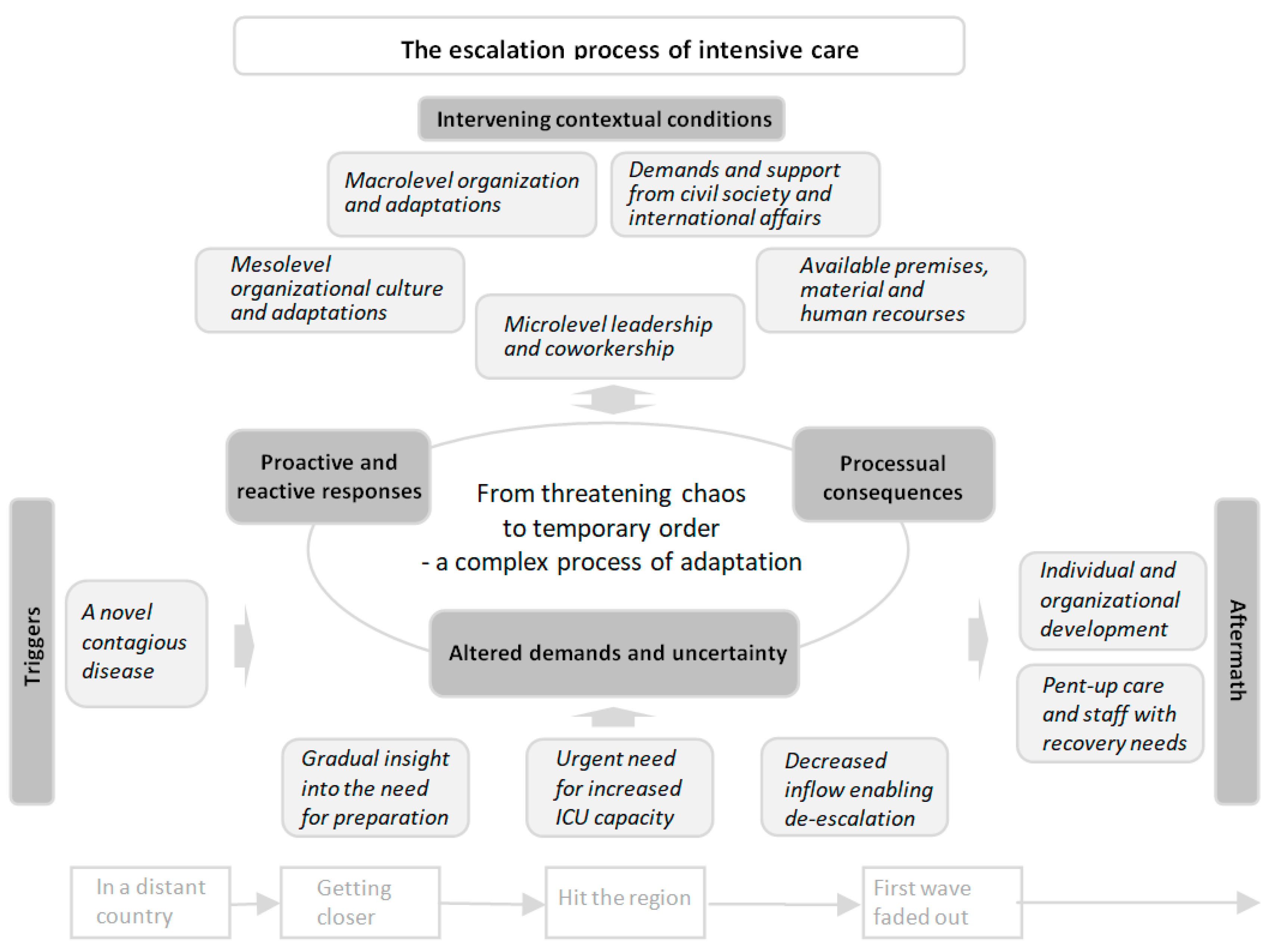

Based on the process of analyzing the participants’ stories, an overall conceptual model of the escalation process of intensive care (EPIC) emerged, and clinical recommendations regarding how to optimize the prerequisites for resilient performance were identified.

The EPIC model includes six main categories and 24 subcategories (see

Table 2); the central phenomenon, which is conceptualized as

from threatening chaos to temporary order through a complex process of adaptation, is the core category that links all categories. The model is visualized in a timeline extending from the emergence of the new disease until the first wave of contagion faded away (see

Figure 1). The complex process of adaptation was iterative, and the different components included in this process interacted continuously. The

triggers of the escalation process created

altered demands and uncertainty, which emerged as the main concern in the process and generated

proactive and reactive responses. The response led to

processual consequences that further altered the demands and forced additional responses in an ongoing and iterative process of adaptation. All categories in the model were interrelated and affected by

intervening contextual conditions at different levels of the system. The process of adaptation continued until the contagion faded away and the

aftermath was discernible, which facilitated a successive transition

from threatening chaos to temporary order. This transition is exemplified by the following extract from an assistant nurse’s narrative:

The first 4 weeks were chaos and a war zone; it was very noisy, and you had no control… Every day, every hour, you thought – I hope nothing goes wrong; I hope no patient dies on my shift… We learned a lot during this time, to be innovative and find different solutions; we were all like MacGyver! (#65).

Below, all main categories of the EPIC model are presented as subheadings with subcategories written in

bolditalics in the text, although they are occasionally written in abbreviated or grammatically modified form to facilitate reading. The 41 clinical recommendations made for different levels of the system regarding how to optimize the prerequisites for resilient performance in intensive care are compiled in

Table 3.

3.1. Triggers

The triggers of the escalation process included four subcategories of causal conditions that contributed to uncertainty and altered demands and started the process of adaptation.

Overall, the novelty of the contagious disease entailed that relevant actors lacked experience and scientific evidence regarding its transmission, treatment and prognosis. This situation led to uncertainty regarding infection control measures and appropriate care strategies as well as difficulty in understanding the threat and the extent of the situation. The unforeseen progress of the pandemic significantly affected intensive care. Initially, at the end of 2019, the disease was delimited and far away; it was thus perceived as ‘of no concern of us’. In early 2020, when reports of cases were drawing closer, the mental state of the staff shifted from ‘if’ to ‘when’ a patient with COVID-19 would arrive to the setting. This situation led to gradual insightsinto the need for preparation, which started to alter the demands on the ICU and the individuals involved, as expressed by one interviewed physician:

There was news about COVID-19, and we started to wake up a little when we saw that it could affect Sweden as well. At first it was pretty obvious that this was probably not as dangerous as it looked. Then, it quite quickly changed to "this could really happen to us". Then, it happened very quickly and it hit us. We escalated intensive care at the last minute, I would say (#28).

The gravity of the situation was initially underestimated, and calculations regarding the disease’s progress, including its potential effects on healthcare, were soon surpassed in March 2020, when the pandemic arrived in the regions substantially earlier and with greater severity than predicted. Additionally, the patients needed more advanced care than anticipated. Hence, an urgent needfor increased ICU capacity arose, which led to significantly altered demands. Eventually, in June 2020, after several intense months, the inflow decreased, and de-escalation was enabled, which once again altered the demands faced by the ICU organization and the individuals involved.

3.2. Altered Demands and Uncertainty

Altered demands and uncertainty, which emerged as the participants’ main concern, included four subcategories. The concern was apparent throughout the escalation process but was most significant when the urgent need for increased ICU capacity occurred and the demand-capacity imbalance in several domains led to a threatening chaos, which is exemplified by the following statement from a registered nurse:

I remember that everything happened at a breakneck speed, and no day was the same. Every day, there were new directives, new solutions, new personnel, new devices, new machines and new patients (#52).

Rapidly altered care conditions was related to the rapidly altered patient inflow and frequently altered care recommendations based on gradually obtained insights into the disease. Additionally, adaptations performed in response to the altered demands further affected the conditions at the front lines. Alongside the circumstances described in all other subcategories, these factors were perceived to increase strain and to impede the ability to manage intensive care in the ordinary manner, although the surge of patients with the same diagnosis and the decreasing inflow of other patients facilitated the standardization of care and the introduction of temporary staff.

Extensive needsfor room and infection control were related to the increased quantity of contagious patients in need of intensive care. The need for infection control required rapid diagnosis, personal protective equipment (PPE) and isolated premises to an extent that had not previously been experienced. This situation led to challenges in intensive care since the test capacity for COVID-19 was delimited, the availability of and experience with PPE was scant, and ordinary ICU premises were too small for large-scale capacity escalation.

Demand-capacity imbalance regarding material and human resources were related to the increased need resulting from the escalation of ICU beds and to the scant availability of resources. The imbalance led to threatening and actual deficiencies in medical technology equipment (beds and mattresses, mechanical ventilators, inhalators, oxygen dispensers, airway suction devices, infusion pumps, vital function monitors, etc.), consumables (material for mechanical ventilators and infusion pumps, syringes and needles, bed linen and diapers, PPE, etc.) and pharmaceuticals (sedatives, inotropes, nutrition, etc.). Specialist competencies related to essential professions were not sufficiently available to meet the staff density requirements for intensive care. The emergency entailed that the ordinary—rigorous and slow—process of recruitment was insufficient, and there was no time for the ordinary introduction of temporary staff, which further increased the demands on ordinary staff. Additionally, the utilization of unfamiliar equipment, consumables, pharmaceuticals and PPE led to uncertainty. Subsequently, when the inflow of patients with COVID-19 decreased, staff capacity exceeded demand, which also generated frustration.

Increased demandson governance, collaboration and communication were related to operational commitment and the challenges -described above. The operational commitment was aimed at providing intensive care to all patients in need of this level of care, including during the pandemic. This task entailed an increased need for an overview, rapid decision making, planning and coordination of resources in collaboration with the whole healthcare organization. Frequent alterations and increased integration within the ICU organization and across different levels of the system as well as the strain on front-line patient care entailed an increased need for information dissemination and staff support.

High information flow, a lack of time and limited access to computers hindered front-line information uptake. Hence, the regular management structure and regular communication and support structure were insufficient, which forced adaptations and led to both proactive and reactive responses.

3.3. Proactive and Reactive Responses

The proactive and reactive responses included six subcategories including adaptations that were continually made both at the ICU management level and in front-line patient care throughout the whole escalation process. This situation was explained by one interviewed physician who served in ICU crisis management as follows:

We had to lay the rails while driving, and it turned out well. As good as it gets when you do that, of course. But there were a lot of decisions that were very ad hoc. It was just like this, "okay, now we'll do this," "well, no, we'll do it like this instead," and we barely had time to keep a log of all the changes we made (#38).

Preparing and planning to the best of one’s ability was indicated by some structural adaptations that were proactively planned and coordinated. For example, prepandemic measures were taken by individuals as well as the ICU organization to prepare for eventual cases of COVID-19 in the regions, including the escalation/de-escalation plans based on different scenarios. However, due to altered demands, it was necessarily to adjust plans continuously, and a large proportion of the adaptations were reactive, intuitive, ad hoc solutions driven by an immediate need. For example, an initial decision to store emergency equipment outside the isolated COVID ICU was adjusted when an unexpected event occurred and the equipment was quickly relocated inside the ICU.

Additionally, the initially rapid progress of the situation entailed limited foresight with regard to planned adaptations, sometimes on an hourly basis. As time progressed, insights and experience increased, and more proactive adaptations became possible, especially during de-escalation.

Reorganizing the management and information structure was performed as a response to the altered demands on governance, collaboration and communication. The decision structure was adjusted by establishing an ICU crisis management group. This group performed needs and capacity planning, monitored the current situation, and tried to compensate for deficiencies; however, it was inherently required to establish priorities regarding how to use existing human and material resources. The ICU management also initiated actions at a higher level of the system, guiding decisions at the mesolevel, facilitating collaboration among departments, and the overall prioritization and redistribution of resources within the region and to some extent also nationally.

A structure for seeking and compiling up-to-date experiences with and evidence regarding the disease and progress of the pandemic was developed. Additionally, the management established strategies for disseminating information to front-line staff through e-mail newsletters and daily meetings. This information included the progress of the pandemic, reorganizations, and new directions and guidelines. These information channels were complemented with strategically placed updated notes. Additionally, a considerable amount of information was disseminated among staff members informally by the “jungle drum” to supplement the formal information.

Prioritizing and reorganizing patient flow was performed to mitigate the strain on ICUs and concentrate the available resources to address the most urgent need. Resource availability for intensive care was increased by deprioritizing nonimperative care and other activities. Admission to the ICU was restricted to patients who were in need of invasive mechanical ventilation. Rapid computed tomography scans for possible COVID-19 cases were organized to speed up diagnosis. Standardized criteria, including scores for fragility and comorbidity, were developed and used to determine whether the individual patient would benefit from invasive ventilation. When patient inflow peaked, ICU capacity in other regions was utilized. In one region, an operational leadership level was established to coordinate around-the-clock patient flow in and out of the ICUs as well as among hospitals in the region and eventual transportation to other regions.

Restructuring and compensating premises and material resources started during preparation and continued throughout the escalation process. Eligible premises were adapted to meet the needs of infection control, and temporary ICUs were established in large premises that were normally used for surgery and postoperative care. Equipment, consumables and pharmaceuticals were redistributed from other parts of the healthcare organization and coordinated by designated staff. Emergency procurement was performed, and substitute equipment, trademarks and treatments were utilized. For example, simple beds without pressure relieving functions, outmoded mechanical ventilators and ventilators that were made only for short-term anesthesia were utilized. The lack of injection pumps for precise individualized distribution and the low availability of regular sedatives entailed that the ordinary regimen was substituted with pharmaceuticals that did not require pumps. The staff also prioritized patients in terms of the urgency of their need for advanced equipment, relocated material and performed trade-offs in patient care, including by stretching the margins of safety for consumables by extending use time and reusing disposables. Additionally, PPE trademarks without regular quality certificates were used.

Redistributing staff and adjusting roles were responses to demand-capacity imbalances in terms of human resources. The first response was utilizing overtime and adapting the working schedules of ordinary ICU staff and managers. When this approach turned out to be insufficient, staff from other parts of the organization were redistributed to supplement the ICU. Additionally, rental staff and staff with ICU competency from other regions were engaged. The urgency of the situation entailed that staffing was prioritized over qualitative introduction, and ordinary recruitment procedures and competence requirements were bypassed. To compensate for deficiencies in terms of ICU competence, the staff-patient ratio was increased, thereby substituting staff quality with staff quantity. Unlike the ordinary organization, according to which physicians were on call during evenings and nights, physicians were allocated to the ICU around the clock, and their role was restricted to inside affaires in the ICU. Task-shifting was performed by engaging external assisting staff (physicians in training, counselors, pharmacists, other healthcare professionals and janitors, etc.) to handle contact with the patients’ families, keep patient records, handle administration and serve supplies.

The roles and responsibilities of ordinary ICU staff were extended to include caring for several patients, coordinating care inside the ICU and simultaneously supervising temporary staff. The lack of a proper introduction was compensated by “learn by doing”, collaboration and collegial support when utilizing unfamiliar equipment, pharmaceuticals and PPE, consciously making trade-offs regarding safety measures and taking into account risks with the goal of providing care.

Alterations and trade-offs in patient care were a response to the conditions at the front lines. Limited knowledge of COVID-19 was managed by drawing on evidence concerning similar diseases. Due to infection control and integrity issues in the large temporary ICUs, visiting restrictions were implemented, a daily routine for calling families was established, and visitors were allowed only for dying patients. To increase efficiency, care in the ICU was reorganized to be more propulsive, with tests and treatments being performed around the clock regardless of night rest for the patients. Procedures, routines and treatments were streamlined and standardized, although they were frequently modified due to altered recommendations and situations of deficiency. Staff counteracted chaos by remaining one step ahead, planning and coordinating activities within the ICU. To address emergencies and enhance patient safety, checklists and boxes for intubation were prepared.

Alternative techniques and treatments were used to compensate for deficiencies. For example, the insufficient calculation of fluid balance was compensated with frequent echocardiography, and invasive mechanical ventilation was applied more frequently due to the lack of high flow oxygen equipment. Communication issues due to noisy environments and the use of PPE were mitigated with the use of simplified language and increased use of body language. Staff continually established priorities among patients and tried to distribute resources to the patients with the most urgent need. As described by a statement made by a registered nurse,

There were a lot of changes in my way of working that I, as an ICU nurse, had to make or completely let go of to be able to handle the situation. ... I had the feeling that patient safety was lower than in the case of regular ICU care even though we all did the best we could for the patients to survive and receive relatively safe care (#47).

However, the diluted competency and heavy workload forced the prioritization of essential life-saving measures, which entailed trade-offs with regard to ordinary care activities, deprioritized administration, such as documentation, reporting adverse events, ensuring the flow of updated information, and a decreased focus on personal wellbeing.

3.4. Intervening Contextual Conditions

Intervening contextual conditions at different levels of the system included five subcategories that, in addition to the triggers, affected the whole process of adaptation.

Microlevel leadership and coworkership associated with great commitment and responsibility among front-line staff and ICU management was perceived to be the main enabler of the escalation of intensive care capacity. One manager’s narrative expressed this situation as follows:

I could sense a tremendous loyalty within the organization that made the impossible possible. I’m really impressed with how quickly the organization was put together; the employees just fixed it! (#23).

The crisis led to a joint focus on managing the situation. Preexisting routines and clinical operation protocols provided a solid base for performance, and competent ordinary staff facilitated the supervision of temporary staff. The professionals also noted that they were used to manage emergencies and collaborate in temporary teams, thus facilitating adaptation, flexibility, innovative solutions and collegial support. The continuity of coworkers and responsiveness to individuals’ different competences were perceived to facilitate collaboration. A nonhierarchical team climate promoted bottom-up initiatives but also led to difficulties with regard to articulating and accepting a chain of command, which sometimes aggravated distinct decisions.

Available premises as well as material and human resources affected the demand-capacity balance and the ability to adapt. Large premises with access to oxygen and compressed air as well as the possibility of isolation facilitated the establishment of temporary ICUs with large cohorts. An existing patient record system that enabled information access from a distance facilitated rapid assessment and provided an overview of the situation. Although partly mitigated by mechanical ventilators drawn from a national crisis stockpile and eventually borrowed military PPE, scarce spare medical equipment, shortages in crisis stockpiles of pharmaceuticals and consumables, and increasing global needs also limited the availability of material resources. The availability of human resources was limited by the prepandemic staffing situation at the border with regard to ordinary operational commitment and a national lack of intensive care competency that limited the availability of rental staff.

Mesolevel organizational culture and adaptations affected the possible ways in which ICU management could manage the situation. The organizational culture implied a trusting mesolevel leadership. This situation allowed ICU management to exercise great autonomy at the microlevel and facilitated prompt actions. Regional crisis management was established. However, the response at the mesolevel and macrolevel was initially perceived as insufficient, which caused actions to be taken at the microlevel. As described in a narrative related by one manager,

In general, you can say that the response in our region was driven by the operational level. It was mainly ideas and initiatives from the Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care and the Department of Infectious Diseases that created the action plans that formed the basis of the region's way of facing the pandemic. Many decisions were made locally, anchored with partners and realized before senior management was informed of what was happening. From my side, there is both a frustration that the management did not act and a relief that what we said at the operational level was listened to (#68).

Collaboration among departments and hospitals in the region was facilitated by a sense of emergency. The general desire to contribute caused ordinary bureaucracy and economic constraints to be set aside, which enabled people to develop rapid solutions to emerging issues such as the reorganization of premises and resources. The redistribution of staff was facilitated by prioritizations sanctioned at the mesolevel, which led to the suspension of nonimperative care and other commitments. Stricter ICU admission criteria were adopted by new intermediate units to care for patients who were in need of advanced care without mechanical ventilation. Additionally, early discharge from the ICU was facilitated by new step-down units for rehabilitation. ICU management was also provided with administrative support from the HR and IT departments. Practical support was provided by the infection control department, pharmacists, and the service department to support supply and cleaning. Mental health support and economic compensation for staff working with COVID-19 were also provided; these measures were appreciated but perceived to be insufficient.

Macrolevel organization and adaptations also affected intensive care. Directives regarding restrictions, PPE and ethical priorities were provided by national authorities. Dissemination of the knowledge that had been obtained was facilitated by professional associations and informal networks via social media and e-mail groups. Before the pandemic, there was no national coordination of intensive care, which impeded the provision of initial support. As one physician concluded during an interview,

It was quite late that the door to other hospitals was opened among our intensive care units in the country… If you have had a different mindset, that we are together in this, Sweden is ONE intensive care clinic… Then, I think, we would have managed better (#28).

As a result of diverse national disease dissemination and informal contacts, the transportation of patients to less strained regions became possible, and burdened regions could be supported through the provision of voluntary intensive care competencies by regions with fewer COVID-19 cases. Over time, national ICU capacity was monitored, and transportation was coordinated and organized. This assistance was appreciated, although a lack of understanding of local qualifications sometimes aggravated the optimal choice of supporting ICU.

Demands and support from civil society and international affairs that affected intensive care included the inflow of patients as well as support from trade unions, spiritual leaders, family and friends, media reports and support from the public. For example, the media reported the staff members as heroes, and the public organized food distribution to staff, all of which strengthened their fighting spirit. However, family demands and worries sometimes added to the perceived strain, and some restrictions in society also aggravated the possibility of commuting to work using public transportation. Additionally, international affairs affected the ICU. For example, competition and barriers to transportation and export obstructed purchases of essential equipment and consumables. On the other hand, lessons learned and evidence found in other countries were disseminated and utilized.

3.5. Processual Consequences

In the process of adaptation that occurred during the escalation, three subcategories of consequences emerged as a result of the adaptations implemented. This situation was described by a registered nurse in a narrative as follows:

It was terrible! The room was not adapted for ICU care. I had never been to the ward and didn’t know the premises; the staff who would help were not used to intensive care, so I had to supervise them as well, even though I had two really ill ICU patients… This day was absolutely not safe for the patients! (#45).

In turn, the processual consequences further altered the corresponding demands and forced additional adaptations. The subcategories were interrelated, as working conditions affected quality of care and patient safety and vice versa, and both aspects were affected by and contributed to managing commitment and learning. One interviewed physician described this situation as follows:

It’s been an incredible journey that you were not prepared for. But that it worked, sort of. It's really cool (#26).

Managing commitment and learningover time was indicated by the provision of intensive care to all patients in need of this care. Despite the threatening chaos, it was possible to provide a basic level of intensive care, and it was never necessary to implement the emergency ethical priority directive from the National Board of Health and Welfare. When the operational leadership of intensive care was transferred to a regional coordinator, a helicopter perspective was created; patient flow and overall care directives were perceived as efficient, while a lack of these functions led to disorganization and fluctuating care. Escalation plans facilitated proactive adaptations, although the rapidly altered demands also resulted in limited foresight and ad hoc solutions. The reorganization of ICU management and regional crisis management was considered to be successful because it enabled overall control and because alterations and measures could be rapidly developed and implemented.

The compilation of unambiguous information and daily meetings with the management facilitated compliance with alterations, while inconsistent information and lack of meetings led to insecurity. Large cohorts facilitated the optimal distribution of knowledge and competence, unlike in ordinary ICUs. Hence, intensive care competence was successively disseminated to other professionals, the experience of temporary staff members increased, roles were settled, and patient care became routine. Over time, knowledge of the disease also increased, which led to improved treatment and less insecurity. Demand-capacity imbalances were mitigated by increased resources, the decreasing inflow of patients and organizational learning.

Diluted competence, impaired quality of care and patient safety were related to demand-capacity imbalances and forced trade-offs. The lack of ICU competency on the part of temporary staff entailed that, under the supervision of a few ordinary staff members, patients received care from staff without specialist competence. This diluted competence, high workload and strained staff limited time with patients and partly forced preventive care to be set aside, which was perceived to dehumanize the patients. The provision of care based on evidence concerning other diseases and insufficient forums for the exchange of experiences led to some disagreements regarding treatment strategies. Overall, this situation led to difficulties in making appropriate individual plans for patients, which affected the continuity and quality of care.

Substitute pharmaceuticals and equipment entailed unnecessary deep sedation and partly suboptimal ventilation, which prolonged the time spent on mechanical ventilation. This situation was perceived to put further strain on the ICU capacity and to affect patient outcome negatively. The staff was forced to manage medical equipment for which they were not trained, and stretched margins of consumables also led to risks to patient safety. Initially, PPE with long sleeves and crowded premises led to the dissemination of hospital-acquired infections. Less frequent position changes and suboptimal mattresses led to pressure ulcers that were typically avoidable. The prioritization of patients with COVID-19 who were in need of invasive mechanical ventilation was also perceived to impact care quality for other patients negatively. One physician described this situation in a narrative as follows:

What has been tough is that we have not had general ICU beds, which I think has meant that patients with higher monitoring needs have ended up in a regular ward or that we have had to transport unstable patients unnecessarily (#35).

The transportation of critically ill patients exposed them to increased risks. On the other hand, the professionals noted that without those trade-offs, some patients would have been rejected from intensive care with even more catastrophic consequences for patient safety.

Impaired work environment and working conditions were related to high demands in relation to control in the situation on the part of both management and staff. Temporary large ICUs were utilized without safety inspections. These premises were physically stressful environments that feature high levels of noise, heat and crowding. A suboptimal design created difficulties in reaching medical equipment and material. On the other hand, the large cohort enabled resource allocation and the surveillance of patients as well as collegial support and the dissemination of knowledge.

Continuously changing demands and adaptations, work schedules that were changed at short notice, new colleagues, and altered roles and responsibilities were perceived as stressful and contributed to staff feeling like game pieces. PPE entailed both security and physical discomfort and impaired people’s ability to interact and communicate with patients and colleagues. The deficiency of PPE, the use of replacement products and frequently altered recommendations created distrust and concern with being sick and disseminating that sickness to loved ones. The redistribution of staff placed administrative burdens on first-line managers, which limited their ability to support staff. Overall, impaired working conditions affected the social lives and wellbeing of both staff and managers.

3.6. Aftermath

As the first wave of COVID-19 faded away, the aftermath of the escalation process was discernible, as described by two subcategories. This ambiguous experience was summarized in a narrative by a registered nurse as follows:

It's like an experience that I would have liked to have avoided in a way, but now that it's here, I don’t want to be without it…How we did in March-April, we didn't do at all in May-June. We did it differently, treated differently; we learned a lot… At that time, you were so up to it in some way, high on adrenaline or what should I say. Then, when you got a vacation, which we actually got for the summer, the air went out of you. And the air hasn't really returned yet… So, there are thoughts about both the present and the future and how people will cope (#80).

Individual and organizational development was indicated by many of the involved staff, who perceived personal development and noted that they were proud of what had been accomplished. Compared to the prepandemic situation, the value of external staff, such as physiotherapists, clinical pharmacists and cleaners, was perceived to have increased, and previous organizational barriers were overcome. Additionally, the adaptations that the crisis necessitated also entailed the rapid and successful implementation of improvements and efficiency increases that had been discussed but not implemented before the pandemic. Some type of measures that had previously rarely been performed, such as prone position, became routine and performed with less concern.

After the first pandemic wave, knowledge of the future development and prognosis of the pandemic was still scarce, but lessons had been learned regarding the dissemination, treatments and prognosis of the disease. The establishment of local stock-piles of consumables and pharmaceuticals was initiated. Insights into necessary considerations, including those related to crisis management and information dissemination, were obtained. Compared to the prepandemic level, preparedness for the outbreak of potential diseases was perceived to have improved. The pandemic was also perceived to elicit a general focus on and understanding of the importance of intensive care, which facilitated recruitment and led to the allocation of resources for permanently increased ICU capacity.

Pent-up care and staff with recovery needs were indicated by the tremendous backlogs that resulted from the postponement of nonimperative care. Hence, many patients were waiting to undergo surgery, assessments and other treatments, which caused the staff to worry. The adaptations implemented to manage the escalation of intensive care were also accomplished at the expense of exhausted and sometimes traumatized staff. Despite the need for recovery, they were required to manage the pent-up care needs for other groups of patients, which left them no time for relaxation. Additionally, uncertainty regarding eventual new outbreaks of the disease and disappointing staff policies regarding redistribution, schedules, support and financial compensation impaired their faith in the future.