1. Introduction

In China, the use of cemented aeolian sand-fly ash backfill (CAFB) material to improve the surface subsidence and environmental damage caused by coal mining is in its embryonic stage(Zhou et al., 2020). Yushen mining area, located in the hinterland of the famous Yushenfu-Dongsheng coalfield, known as one of the world’s seven big coalfield, has hundreds of coal mines of various sizes distributed in the Yushen mining area, which are located in the Maowusu Desert and have harsh geological conditions. It can reduce the damage to the surface environment caused by large-scale coal mining, which conveys the large amount of covering aeolian sand on the surface to the mining area through pipeline pressurized(Bian et al., 2009; Chandel et al., 2009; Horiuchi, 2000; Sivakugan et al., 2015, 2006; Szczepanska and Twardowska, 1999; Zha et al., 2011). CAFB material is usually considered to be a high-density, non-segregating mixture containing 68%-75% solids. Hydraulic binder such as cement, in amounts of 8-12% of the total CAFB material, is an integral part of any CAFB material, which gradually adds additional bonding and mechanical strength during the maintenance process, where increasing the solids content of the CAFB mix is more economical than increasing the amount of binder, which accounts for 75-80% of the cost of the filling operation(Ferraris et al., 2001; Williams et al., 1999). Typically, fresh CAFB is transported by gravity or by a pipeline pumping system to the downhole mining area. However, in the process of transportation, CAFB with very low water/ash ratio (W/A) may cause huge frictional resistance and pipeline blockage due to its rheological properties changing with the hydration age. The use of a single aggregate aeolian sand in the CAFB slurry will cause large bleeding in the underground mining aera, worsening the underground operating environment, and the loss of the cement, fly ash and water mixed slurry will be reduced the strength of the filling body, the author innovatively proposes the high concentration filling cementing material CAFB, which is prepared by mixing aeolian sand, coal gangue, cement, fly ash and water in a certain ratio, studying the influence of coal gangue dosage and hydration time on the rheology of CAFB slurry, optimizing the material ratio, reducing the frictional resistance of slurry in the pipe, realizing efficient transportation, and improving the underground operating environment and improving the strength of the filling body(Klein and Simon, 2006). The yield stress and viscosity are the key rheological parameters for evaluating the CAFB material transport capacity in the design of pipeline reticulation systems. The yield stress is typically realized as the effect of conditions of mutual attraction between individual particles, which can aggregate to form suspensions, which interact to form a continuous three-dimensional mesh structure extending throughout the volume. On this basis, the yield stress is related to the strength of the coherent network structure as the force needed to break down the structure, especially the network bonds or the breaking of the connecting bonds of the structural flow units. There have been many studies of the analysis of colloidal stability and solid particle surface properties under yield stress conditions. Many experimental methods have also been used to study the effect of particle concentration, size, particle size distribution, shape, surface activity, etc. on the yield stress values of various suspension systems (Kaushal et al., 2005; Kumar et al., 2003). The yield stress is the critical shear stress that causes irreversible plastic deformation and allows the fluid to flow in the pipe. The yield stress must be in the optimum range to allow laminar transport of CAFB materials in the pipeline, (velocity range 0.1 m/s to 1.5 m/s) without solids settling (Yang et al., 2019). The viscosity is the frictional resistance of two layers of concentrated fluid in the flow state. It is well known that the rheology of CAFB is influenced by various factors such as solid concentration, cement type and its dosage, chemical additives and their dosage, particle size distribution, water chemistry and temperature. In addition, the microstructure of CAFB gradually changes during its transport due to the evolution of cement hydration products. CAFB is considered as a non-Newtonian fluid because the shear stress at any point along the pipe cross-section during flow depends on the shear rate and time; therefore, the time-dependent rheology of CAFB is an issue of interest (Panchal et al., 2018). The water-reducing effect of plasticizer is mainly realized through the surface-active role of plasticizer (Ferraris et al., 2001; Klein and Simon, 2006; Williams et al., 1999). Plasticizer in the solid-liquid interface to produce adsorption, reduce surface tension, improve the surface wetting state of cement particles, fly ash particles and gangue particles, so that the mixture dispersion of thermodynamic instability is reduced, so as to obtain relative stability(Kaushal et al., 2005; Kumar et al., 2003; Panchal et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019). Plasticizer produces directional adsorption on the surface between the particles, so that the surface of the particles with the same charge, electrostatic repulsion, which destroys the flocculation-like structure between the particles, so that the particles are dispersed. For mines filled with CAFB material, the key to successful pipeline transport lies in the rheological properties of the filled slurry, which is ultimately determined by the particle gradation. A reasonable material gradation should be selected to ensure uniform gradation, slow down the settling of aggregate particles to block the pipeline, and ensure that the slurry has good fluidity and stability with low overflow water over a period of time. In order to study the influence of the particle size gradation and hydration time of aeolian sand and coal gangue aggregate in different ratios on the rheological characteristics of the filling slurry, this paper elaborates the intrinsic connection between the rheological indicators of the filling slurry and the particle gradation parameters through rheological tests, so as to provide reference for the ratio test of aggregate, crushing and screening as well as the research of long-distance pumping and pressure conveying technology(Wu et al., 2018, 2017, 2015a, 2015b).

2. Rheological model

2.1. Rheological parameters analysis

Yield stress and viscosity are the two basic parameters to characterize the rheology of a slurry. The yield stress can be divided into dynamic yield stress and static yield stress. The mass fraction of the slurry with yield stress is related to the content of fine particles, the smaller the particle size or the higher the content, the lower the mass fraction of the slurry with yield stress. Viscosity reflects the size of the internal friction angle of the slurry flow itself, which is the macroscopic expression of the microscopic action of fluid molecules. The slurry viscosity is related to the particle size, distribution, mass fraction of solid particles, energy exchange between solid and liquid particles and other factors and related to the hydration reaction of cement and the generation rate of products of volcanic ash reaction(Conte and Chaouche, 2019).

2.2. The rheological model

The flow state of the material in different positions in the pipe can be roughly divided into “structural flow”, “laminar flow” and “turbulent flow” according to the flow velocity, and the transmission characteristics are different from the two-phase flow movement law. When the mass fraction of slurry reaches a certain level, the slurry becomes very viscous and the transmission characteristics change greatly along the pipeline, and the slurry moves in a “plunger” shape. Domestic and foreign researchers have confirmed that the Reynolds number of pipeline transporting high mass fraction (paste) slurry is much lower than the Reynolds number from laminar flow to turbulent flow, and the rheological model of high mass fraction slurry is suitable to use H-B model, whose rheological characteristic curve is shown in

Figure 1:

where

is the shear stress, Pa;

is the shear rate, s

-1,

is the viscosity, Pa

.s;

is the initial yield stress, Pa; n is the fluidity index. When n = 1,

= 0, it is a Newtonian body; when n = 1,

0, it is the Bingham body; when n > 1, it is the swelling body; when n < 1, it is pseudoplastic body

(Rubio-Hernández 2018).

3. The properties and characteristics of materials

The following details the characteristics of the materials used in this study, such as aeolian sand, coal gangue, cement, fly ash and chemical admixture.

3.1. Aeolian sand

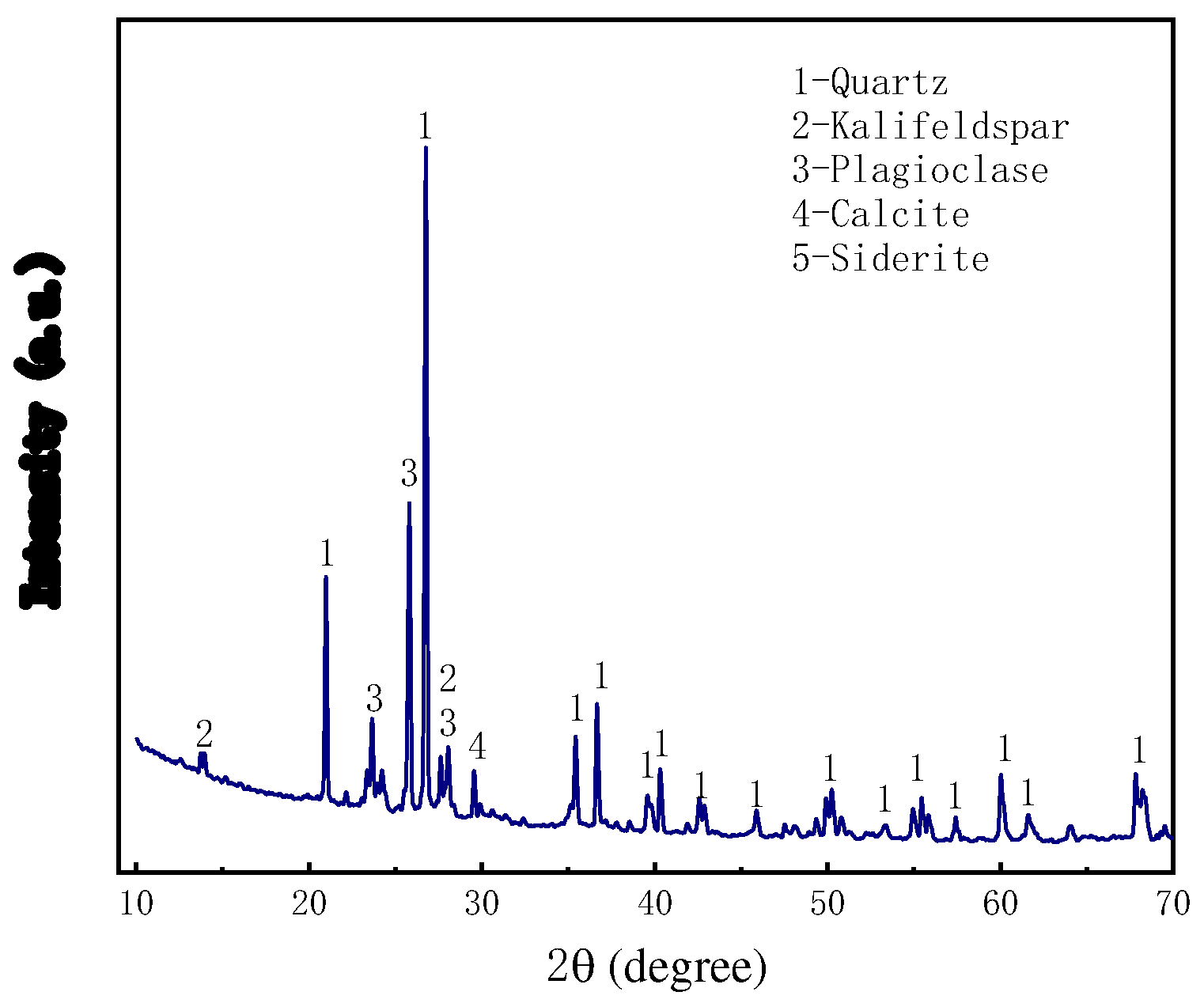

The samples were collected from near the Shiyaodian coal mine in Shenmu, Yulin, Shaanxi, China. The mineralogical analysis of the aeolian sand was carried out using an X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectrometer (Japan Rigaku SmartLab), as shown in

Figure 2. The particle size analysis was performed using a particle size analyzer (NKT5200-HF), which showed that the particle size of the aeolian sand was mainly distributed between 100 μm and 300 μm in Figure 6. The chemical composition of the aeolian sand was analyzed by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer, as shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Coal gangue

The coal gangue samples were collected from Shenmu Shiyaodian coal mine, Yulin, Shaanxi, China, and the coal gangue was crushed below 3 mm by mechanical processing, and the particle size analysis was carried out using a particle size analyzer (NKT5200-HF), and the results showed that 50% of the coal gangue was less than 500 μm in size in Figure 7. The mineralogical analysis of the coal gangue was carried out using an X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectrometer (Japan Rigaku SmartLab), as shown in

Figure 3, and the chemical composition of the coal gangue was analyzed using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer, as shown in

Table 2.

3.3. Fly ash

Fly ash samples were collected from the Shenmu Guohua Power Plant in Yulin, Shaanxi, China, and particle size analysis was performed using a particle size analyzer (NKT5200-HF), which showed that the fly ash particle size mainly ranged from 0 μm to 300 μm in Figure 8. The mineralogical analysis of the fly ash was carried out using an X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectrometer (Japan Rigaku SmartLab), as shown in

Figure 4 and the chemical composition of fly ash was analyzed using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy, as shown in

Table 3.

3.4. Cement

The cement was ordinary Portland cement 425# (P.O. 42.5), the bulk density is 3100 kg/m

3,and the initial and final setting time are 165 min and 231 min respectively, and the compressive strengths at 3d and 28d are 18.4 MPa and 46.4 MPa respectively, and the particle size analysis was performed using a particle size analyzer (NKT5200-HF), and the results showed that the cement particle size mainly below 100 μm in Figure 9. The mineralogical analysis of the cement was carried out using an X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectrometer (Japan Rigaku SmartLab), as shown in

Figure 5 and the chemical composition of the cement was analyzed using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer, as shown in

Table 4.

3.5. Chemical admixture

Master Glenium 7500 (Master G), a product of the chemical company, Badische Andilin und Soda Fabrik (BASF), was used as the plasticizer in the CAFB mix. It is a full range water reducing admixture generally used for workability improvements and early strength achievement. It meets the ASTM requirements for high range water reducing admixtures.

Figure 2.

X-ray diffractogram of aeolian sand

Figure 2.

X-ray diffractogram of aeolian sand

Figure 3.

X-ray diffractogram of coal gangue

Figure 3.

X-ray diffractogram of coal gangue

Figure 4.

X-ray diffractogram of fly ash

Figure 4.

X-ray diffractogram of fly ash

Figure 5.

X-ray diffractogram of cement

Figure 5.

X-ray diffractogram of cement

Figure 6.

particle size distribution of aeolian sand

Figure 6.

particle size distribution of aeolian sand

Figure 7.

particle size distribution of coal gangue

Figure 7.

particle size distribution of coal gangue

Figure 8.

particle size distribution of fly ash

Figure 8.

particle size distribution of fly ash

Figure 9.

particle size distribution of cement

Figure 9.

particle size distribution of cement

4. Instructions for rheometer and vane spindle

The rheological behavior of CAFB is measured using the RheolabQC rheometer (Anton paar RheolabQC, Germany) with a four-blade sensor

(Dzuy & Boger 1985). The geometry of the vane sensor corresponds to a cylinder with a diameter of 22 mm and a height of 40 mm. The rheometer can be operated in a controlled shear stress or shear rate mode. The rheometer has shear rate from 1

10

-3 s

-1 to 4

10

3 s

-1, shear stress from 0.5 Pa to 3

10

4 Pa, depending on the measurement system, and viscosity from 1 Pa

.s to 1

10

9 Pa

.s. The accuracy of the rheometer is 0.1%. The rheometer works on the principle of searle. The vane spindle has an aspect ratio (height/diameter) of 1.8. The geometry of the blade spindle effectively eliminates any wall slip effects, suppressing any significant interference with the sample that may result during the immersion of the blade into the sample prior to any measurement, thus allowing the paste to yield under the static conditions of the material itself. It will be very important that the suspension is thixotropic in nature. In the phenomenon of wall slip, an extremely thin film of low concentration solid lubricant is formed in the material near the rotating surface of a concentric cylindrical or conical plate rheometer. As a result, the shear stress and viscosity in the film are much lower relative to the remaining dense concentrated material, and therefore the true rheological behavior of the concentrated material may not be captured. Therefore, the vane is best suited for the thixotropic behavior of highly concentrated suspensions. It is important to note that the depth of the CAFB suspension and the diameter of the sample container (beaker or cup) should be at least twice the length and diameter of the vane to minimize the effects caused by rigid boundaries. For satisfactory measurements with the vane spindle, following criteria are followed as per:

,

,

, and

(

Figure 7). The submerged depth of vane is described by the distances

and

, while H is the height of vane blades as shown in

Figure 10. Here, the diameters of the vane spindle and the sample container are calculated respectively.

Figure 10.

Dimensions of four bladed vane and sample container.

Figure 10.

Dimensions of four bladed vane and sample container.

5. Specimen preparation and experimental methods

The CAFB’s ingredients i.e., solid concentration

Cw%, aeolian sand dosage

Bw%, coal gangue dosage

Dw%, fly ash dosage

Ew%, cement dosage

Fw%, plasticizer dosage

SP(%) and water content

Gw% which are used insubsequent sections of this paper are calculated from the following equations(Eq.(2a) to Eq.(2g)):

where M

water is mass of water in the paste fill; M

dry-solid is mass of aeolian sand, coal sand, Portland cement, and fly ash. M

aeolian-sand is mass of aeolian sand, M

cement is mass of Portland cement, M

coal-gangue is mass of coal gangue, M

fly-ash is mass of fly ash and M

sp is mass of plasticizer. The amount of aeolian sand and coal gangue are varied to prepare different mix composition as shown in

Table 5.

Table 5.

CAFB mixture proportions.

Table 5.

CAFB mixture proportions.

| CAFB code |

1# |

2# |

3# |

4# |

5# |

6# |

7# |

|

77.5 |

77.5 |

77.5 |

77.5 |

77.5 |

77.5 |

77.5 |

|

46 |

43 |

40 |

37 |

34 |

40 |

40 |

|

5 |

8 |

11 |

14 |

17 |

11 |

11 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.05 |

0.1 |

|

17.5 |

17.5 |

17.5 |

17.5 |

17.5 |

17.5 |

17.5 |

|

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

|

22.5 |

22.5 |

22.5 |

22.5 |

22.5 |

22.5 |

22.5 |

Table 6.

Characteristic index of particle size gradation of CAFB.

Table 6.

Characteristic index of particle size gradation of CAFB.

| CAFB code |

d10/μm |

d30/μm |

d60/μm |

d90/μm |

d50/μm |

| 1# |

53.771 |

80.586 |

179.465 |

361.146 |

138.018 |

| 2# |

51.263 |

78.586 |

207.453 |

449.321 |

151.538 |

| 3# |

48.755 |

76.587 |

235.442 |

533.496 |

165.059 |

| 4# |

46.247 |

74.587 |

263.43 |

617.671 |

178.579 |

| 5# |

43.74 |

72.594 |

291.507 |

702.089 |

192.149 |

5.1. Vane test to determine yield stress and viscosity

In the following, the procedural steps for developing a slurry material for rheological evaluation are outlined.

Step 1. Initial mixing: The air-dried coal gangue are thoroughly mixed with certain proportion of aeolian sand, cement, and fly ash using spatula in a mixing container. Then specified amount of tap water followed by a certain proportion of SP is added and homogenized thor-oughly using the electrich and blender at high shear (+1000rpm) for 5min.

Step 2. Final mixing: The slurry was then loaded into a 500 mL beaker, and finally the container loaded with the slurry was assembled with the rheometer for subsequent rheological tests, with a four-blade rotor gradually entering the middle of the beaker and inserted with the slurry sample undisturbed for 30 seconds to allow the mixed slurry to reach its structural balance and at least partially recover its initial structure and strain state.

Step 3. Determination of yield stress and viscosity: For each sample, rheological curves describing the correlation between shear stress and shear rate were obtained experimentally. The rheological parameters describing the rheological properties of the slurry included yield stress and viscosity. The yield stress is the stress value at which the material just starts to yield to a state transition, and the shear rate of the rheological curve is from 0.01s-1 to 150s-1 with an interval of 0.05s-1. The Herschel-bulker rheological model was used to fit the measured rheological curves. In the fitted curves, the intersection of the shear stress curve with the longitudinal coordinate (longitudinal intercept) is the yield stress, the viscosity is the slope of the fitted curve, and the viscosity is the ratio of shear stress to shear rate (Dzuy and Boger, 1983; Yang et al., 2014).

Step 4. The above process was repeated for samples from the same batch of slurry to obtain different parameters i.e., 3 min, 30 min, 60 min after sample preparation. the hydration age was chosen to cover a wide range of transport times encountered during the slurry backfill tests. The shear test was performed using a controlled shear rate by placing the rotor in a 500 mL beaker for rheological testing, rotating it at a variable shear rate, dispensing the slurry several times and taking the average value for multiple measurements to eliminate experimental errors, and recording the corresponding shear stress and viscosity in real time. The test is repeated three times for each slurry sample to ensure reproducible results.

5.2. Microstructural analysis

To gain a more in-depth understanding of the effects of different factors on the cement hydration process in CAFB, microstructure analyses, including thermal analyses thermogravimetry (TG) and differential thermogravimetry (DTG), were conducted on the prepared cement fly ash paste (CFP) samples of the CAFB. The CFPs were prepared at a water / binder ratio of 1, cured at room temperature for 1 h and 2 h, respectively. Before testing was carried out, the specimens were dried in an oven-dried at 45°C until a constant mass was attained.

The thermal analyses were carried out by using a simultaneous thermogravimetric analyzer and differential scanning calorimeter (SDT) from TA Discovery TGA 550. The dried samples were placed on a plate and heated under an inert nitrogen atmosphere at a rate of 10℃/min from room temperature to 800℃.

5.3. Zeta potential test

Zeta potentials of CAFB samples treated with a different dosage of the plasticizer were measured using Malvern Zetasizer Nano series. The device measures the electrophoretic mobility of suspended particles based on phase analysis light scattering (PALS). The zeta potential of the particles is evaluated using the Henry equation.

5.4. Monitoring program

To gain additional insight into the reaction mechanisms responsible for the rheological behavior of the CAFB with varying composition, a 5TE sensor was used to monitor the electrical conductivity (EC), while an MPS-6 sensor was used for suction. Each sensor was placed at the middle of a cylindrical plastic container of 10 cm diameter by 20 cm height filled with the CAFB and readings recorded from the time of cast until 2 h.

5.5. Scanning electron microscopy tests

The parts of the dried CAFB specimens were cut into small rectangular specimens (10 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm) with a naturally formed surface. The specimens were placed in a holder with its natural surface facing upwards. The base of the specimens was attached to the holder using conductive adhesive or glue. Finally, micrographs of the prepared SEM specimens were captured using a ZEISS Gemini SEM 300 scanning electron micro-scope with magnifications between 100x and 5000x.

6. Results and discussion

CAFB material is added with different proportions of samples of aeolian sand and coal gangue, along with the growth of hydration time, the rheological parameters yield stress and viscosity of the slurry are measured, and the influence of particle gradation of the slurry and the rheological parameters of the slurry are counted by linear regression method to explore the best combination of material gradation, and reduce the resistance loss of the material in the process of pipeline conveying, and establish the corresponding basis.

6.1. Fitting and analysis of rheological parameters

The linear regression analysis of the experimental results was performed to obtain the indicators of the rheological properties of the slurry under different conditions by Eq. (1), as shown in

Table 7. From

Table 7, it can be concluded that with the extension of the resting time of the slurry, the values of the parameters reflecting the rheological characteristics of the slurry change inconsistently, the initial shear stress of 1#, 2#, 4# and 5# of slurry all increase first and then decrease, and the viscosity of 1#, 3#, 4# and 5# of slurry all increase first and then decrease; with the same resting time, the rheological characteristics of the slurry composed of different materials are different. In the resting time of 30 min, the initial shear stress of 4# and 5# of slurry is larger than the other three groups of slurry. The initial shear stress of 4# and 5# slurry is greater than the other three groups of slurry because the particle gradation of 4# and 5# of slurry is similar, and the volume fraction of fine particles contained in the unit volume is greater, and the rheological model of the slurry is changing as the time grows, the hydration reaction inside the slurry continues, and the number of flocculent network gel products with resistance to mechanical damage is increasing, and the strength is increasing. Comparing the rheological indexes of the characterized slurry in

Table 7, it can be concluded that 1#, 2#, 3#, 4# and 5# of slurry are in swelling body after 3 min of resting, and their rheological indexes are greater than 1. 3# and 4# of slurry are in Bingham body after 30 min of resting, and their rheological indexes are basically close to 1. 1# and 5# of slurry are in pseudoplastic body after 60 min of resting, and their rheological indexes are less than 1.

6.2. The influence of the amount of coal gangue added on the rheological properties of the slurry

From

Figure 11, the relationship between shear stress and shear rate is different from different grades of slurry at different shear rate. The rheological characteristic curves of 3#, 4# and 5 # of slurry are basically the same, and the rheological characteristic curves of 1# and 2# of slurry are basically the same with similar basic laws. With shear rate from 10 to 60, the rheological curves of slurry are pseudoplastic body; with shear rate from 60 to 100, the rheological curves of slurry are Bingham body; with shear rate from 100 to 150, the rheological curves of slurry are pseudoplastic body with a certain yield stress; with the increasing shear rate, the shear stress is also increasing, but the particle gradation of the slurry is not consistent, resulting in the increase of the shear stress of the slurry from 1# to 5# is not the same degree, and the initial shear stress is not the same with the increase of the mass fraction of the unit volume in the slurry, and the initial shear stress of the slurry is also increasing with the increase of the unit volume mass fraction in the slurry, which is basically consistent with the particle size gradation. From 1# to 5# slurry, the viscosity is in the unstable stage, transition stage, stable stage, and the value is decreasing, and the stable stage is basically below 10 Pa

.s. From

Table 6, the median particle size of 1# to 5# slurry are 138.018 μm, 151.538 μm, 165.059 μm, 178.579 μm and 192.149 μm respectively, and the distribution of the particle size of coal gangue can be seen that 50% of the coal gangue is below 500 μm, and the particle size of the aeolian sand is mainly between 100 and 300 μm, from the slurry Proportional distribution, it can be seen that from 1# to 5# slurry, the proportion of aeolian sand is in the decline, but the proportion of coal gangue is in the rise. The mass fraction of unit volume is in the increase, so the median particle size of 1# slurry to 5# slurry is also increasing, and D

10 particle size value is in becoming smaller, and D

90 particle size value is in becoming larger, which indicates that the particle size distribution of the material is more uniform, but, with the increase of coal gangue the initial shear stress of the slurry is getting bigger and bigger, the reasonable particle gradation should not only ensure that the slurry has good rheology, but also make the yield stress of slurry to be in a reasonable range, so that the pipeline’s conveying resistance runs in a reasonable range and reduce the energy loss.

Figure 11.

Distribution diagram of shear stress, viscosity and shear rate after standing for 60 minutes.

Figure 11.

Distribution diagram of shear stress, viscosity and shear rate after standing for 60 minutes.

Figure 12.

Distribution diagram of shear stress, viscosity and shear rate after standing for 30 minutes.

Figure 12.

Distribution diagram of shear stress, viscosity and shear rate after standing for 30 minutes.

Figure 13.

Distribution diagram of shear stress, viscosity and shear rate after standing for 3 minutes.

Figure 13.

Distribution diagram of shear stress, viscosity and shear rate after standing for 3 minutes.

6.3. Correlation between rheological parameters and gradation

If there is a certain correlation between the rheological parameter X

1 and the particle gradation parameter X

2 for different slurries, the correlation is expressed by the following equation.

From the principle of least squares, the correlation coefficient r between the parameters X1 and X2 can be derived. In general, when r< 0.4, there is no or weak correlation between the variables; when 0.4< r < 0.6, there is moderate correlation between the variables; when 0.6 < r < 0.8, there is strong correlation (significant correlation) between the variables; and when 0.8 < r < 1.0, there is very strong correlation between the variables.

The linear regression results between the different parameters were obtained by least squares calculation of the parameters in

Table 6 and

Table 7 according to the correlation equation. The correlations between the viscosity and yield stress of the slurry at 3, 30 and 60 min of standing are shown in

Table 6 and the particle grading parameters are shown in

Table 7, respectively. From

Table 8, it can be concluded that the correlation coefficients of yield stress and D

10, D

30, D

50, D

60 and D

90 of particle size after 3 min of standing are of above 0.98, which indicates that there is a strong correlation between them, because the mass fraction of the slurry with yield stress is related to the content of fine particles, and the smaller the particle size or the higher the content, the lower the mass fraction of the slurry with yield stress. with the growth of coal gangue particle content, 1#, 2#, 3#, 4# and 5# of mixed slurry fine particles are increasing, and the proportion of coarse particles is also increasing, which shows that there is a strong correlation between the yield stress of the slurry and the slurry particle size. with the slurry in the rest 3min, the correlation coefficient of viscosity and D

10, D

30, D

50, D

60 and D

90 of particle size is of above 0.75. This shows that there is a strong correlation between the two, which indicates that there is also a strong correlation between the particle gradation and the viscosity of the slurry.

From

Table 9, it can be derived from the slurry after 30 min resting, the correlation coefficients of yield stress and D

10, D

30, D

50, D

60 and D

90 of particle size is of above 0.86 or more, which indicates that there is a strong correlation between the two, because the mass fraction of the slurry with yield stress is related to the content of fine particles, the smaller the particle size or the higher the content, the slurry mass fraction of yield stress is lower. with the growth of coal gangue particle content, 1#, 2#, 3#, 4# and 5# of mixed slurry fine particles are increasing, the proportion of coarse particles is also increasing, which shows that there is a strong correlation between the yield stress of the slurry and the slurry particle size. With the slurry in the resting 30 min, the coefficient of correlation between viscosity and D

10, D

30, D

50, D

60 and D

90 of particle size reached 0.20, indicating that there is no correlation between them.

From

Table 10, it can be derived from the slurry in the rest 60min, the correlation coefficient of initial yield stress and D

10, D

30, D

50, D

60 and D

90 of particle size are about 0.93 or more, indicating that there is a strong correlation between the two, because the mass fraction of the slurry with yield stress is related to the content of fine particles, the smaller the particle size or the higher the content, the slurry mass fraction of yield stress is lower. with the growth of coal gangue particle content, 1#, 2#, 3#, 4# and 5# of mixed slurry, fine particles are increasing, the proportion of coarse particles is also increasing, which shows that there is a strong correlation between the yield stress of the slurry and the slurry particle size. with the slurry in the resting 60min, the correlation coefficient of viscosity and D

10, D

30, D

50, D

60 and D

90 of particle size are of 0.39 or more, indicating a weak correlation between the two.

From

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10, it can be concluded that the initial shear stress of the slurry basically follows a very strong correlation (3min-30min-60min) with the slurry resting time, and on the contrary, the viscosity of the slurry basically follows a strong correlation (3min)- no correlation (30min)-weak correlation (60 min). Under the same conditions, the particle sizes of D

10, D

30, D

50, D

60 and D

90 have a great influence on the relationship with the initial shear stress of the slurry, and at 3min, the viscosity of each particle size with the slurry has a greater influence.

6.4. Time-dependent evolution of the rheological properties of CAFB with the ratio of aeolian sand / coal gangue

The variation of the yield stress between 0h and 1h for different types of slurry 1#-5# is shown in

Figure 14.

It shows that the age of maintenance has a great influence on the yield stress value of 1#-5# slurry in

Figure 14, in which the yield stress value of 1# slurry increases from 415.16 Pa at 0h to 611.65 Pa at 0.5h; this is mainly because the hydration reaction of cement in the slurry increases with time and the hydration products keep increasing, which causes the yield stress value of the slurry to become largely. It leads to an increase in the frictional resistance between the fly ash particles and gangue particles of CAFB, which enlargements the yield stress (Haiqiang et al., 2016). Furthermore, more hydration products will greatly increase the cohesion among cement particles, fly ash particles and gangue particles, resulting in an increase in yield stress (Klein and Simon, 2006).During the period of 0.5h-1h, the yield stress values of 1#, 4# and 5# slurry were significantly reduced from 611.65 Pa, 779.76 Pa and 919.08 Pa to 410.89 Pa, 725.24 Pa and 705.04 Pa. The reason for this is that the increase of cement hydration products C-S-H, CH, ettringite wrapped in aeolian sand and coal gangue surface, and fill the pores therein, greatly reducing the yield stress of CAFB.

The TG/DTG analysis results experimentally support the increase in hydration products due to longer maintenance period in

Figure 15. It shows the results of TG/DTG analysis of the slurry of CAFB samples for 1 hour and 2 hours. The DTG curve shows two main internal heat peaks, which are related to the rapid weight loss and the main phase transition. The first internal heat peak appeared at 102.92 °C, which the weight loss appeared between 114 °C and 116 °C, and the weight change was 0.430 % within 1 hour. However, the first internal heat peak appeared at 51.36 °C, which the weight loss appeared between 48.13 °C and 81.91 °C, and the weight change was 0.997 % within 2 hours, which was reasons for the dehydration of hydration products, such as C-S-H, carbo aluminates, ettringite, and gypsum (Zhou and Glasser, 2001). In fact, previous studies have also concluded that the decomposition of gypsum and ettringite and the dehydration of some carbo aluminate hydrates occur in the temperature range of 60-200 °C. Two internal heat peaks were found at 637.09 °C, which the weight loss was found between 585.76 °C and 658.12 °C, and the weight change was 6.552 % within 1 hour. However, two internal heat peaks were found at 620.26 °C, which the weight loss was found between 575.44 °C and 639 °C. Comparing the TG/DTG diagrams of the slurry cured for 1 hour and 2 hours, the latter has more weight loss or higher peaks in the temperature range of 60-200 °C. It indicates that the CAFB maintained for a long time will have more cement hydration products (C-S-H, ettringite, etc.) than the samples maintained for a shorter time. It is obtained that the maintenance period on cement hydration process is consistent with the previous conclusion (Phan et al., 2006).

6.5. Time-dependent evolution of the rheological properties of CAFB with plasticizer

Viscosity and yield stress were used to study the rheology of fresh CAFB made with different ratios of plasticizer. At the early stages of preparation, the viscosity of CAFB without addition was a lot higher than that with addition of 0.05 % and 0.1 % as shown in

Figure 17. With moderate additions of 0.05 %, the viscosity decreased from 0.148 Pa·s to about 0.04 Pa·s at 0 h, and this tendency continued for the rest of the maintenance period. Similarly, it shows the development of yield stress in the first 1 hour of mixing in

Figure 16. Likewise, the adding of the plasticizer led to a proportionate reduction in the yield stress of CAFB. In the maintenance period of 1 hour, the yield stress decreased more obviously. The yield stress of 0.05 % admixture content decreased from 652 Pa to 234 Pa, and the yield stress of 0.1 % admixture content decreased to 215 Pa. The increased fluidity observed from the 0.05 % and 0.1 % admixture content may be related to the dispersion effect of plasticizer. It can be seen from that the Zeta potential of CAFB with and without the mixture supports this point in

Figure 18. The zeta potential of CAFB containing 0.05 % mixture was about −10 mV, while the untreated sample was −3.5 mV. This indicates that the repulsion between particles is much higher in the presence of plasticizers. Another explanation for the change in CAFB fluidity caused by the adding of plasticizers is its effect on cement hydration. Due to the increase of repulsive force among cement particles, fly ash particles and gangue particles, less hydration by-products are produced, and the viscosity of CAFB decreases with the decrease of solid content. In addition, the EC monitoring results support the conclusion that the plasticizer postpones the hydration reaction in

Figure 19. The EC of CAFB containing 0.1 % plasticizer was obviously lower than that containing 0 % CAFB. Therefore, the mobility of ions is higher in CAFB without dopants.

It can also be seen that the yield stress of CAFB samples increase smoothly with the maintenance period owing to the hydration process of cement and the surface absorption of poorly crystalline C-S-H gels in

Figure 16. Once the cement is in contact with water, the chemical reaction usually begins (Cui and Fall, 2015). In addition, it can be seen by electron microscope scan that CAFB with maintenance age of 3 d can clearly see C-S-H, CH, ettringite filling around the aeolian sand and coal gangue, which affects the fluidity of CAFB slurry, as shown in

Figure 20.

7. Conclusion

The time-dependent rheological properties of fresh CAFB treated with the Master Glenium plasticizer and cured under different ratio of aeolian sand / coal gangue were studied in this paper. Plasticizer dosages of 0, 0.05, and 0.1% of the total CAFB weight were used. Additional tests such as thermal analysis and zeta potential analysis were conducted to understand the reasons behind the nature of the results observed. The major conclusions based on the results obtained are summarized below.

3#, 4# and 5# slurry flow index change pattern is basically the same, the index n which characterizes the flow property is greater than 1 after 3 min resting, belongs to swelling body; n is close to 1 after 30min resting, belongs to Bingham body; n is less than 1 after 60 min resting, belongs to pseudoplastic body; 1# and 2# slurry in 3-30min flow index is greater than 1, belongs to swelling body, After 60min of resting, the flow pattern of slurry changes n is less than 1, which belongs to pseudoplastic body.

With the increase of shear rate and shear time, the viscosity first gradually decreases and then stabilizes, i.e., the rheological properties of the slurry have the characteristic of “shear thinning”; the rheological properties of the slurry process is the comprehensive embodiment of a variety of model composite properties, with the increase of shear rate, the rheological curve of the slurry shows an upward convex shape, showing a pseudoplastic body-Bingham body-Pseudoplastic body(swelling body).

According to 2# and 3# mixed material, it will be grading configuration aeolian sand, coal gangue, fly ash filling slurry, to ensure long-distance pipeline conveying process slurry flow stability, to ensure smooth pipeline transport.

Curing time (0h-0.5h) results in a higher yield stress of the CAFB. It is because a longer curing time is associated with greater degree of cement hydration products. Curing time (0.5h-1h) results in a lower yield stress of the CAFB. Is is because more hydration products is associated with an decrease in the aeolian sand inter particle frictional resistance of the CAFB.

Addition of plasticizer to the CAFB significantly reduces the yield stress and viscosity of CAFB. An addition of 0.05% of the admixture results in over 65% reduction in yield stress at the time of preparation as well as after 1 h. A similar reduction was observed in the improvement of viscosity. The marginal reduction upon increasing the admixture to 0.1% is much less, indicating that an optimum percentage is around 0.05.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and writing the original draft: Zhijun Zheng Data curation: Junyu Jin Xiaolong Wang Writing, review, and editing: Baogui Yang.

Funding

The authors are very grateful to the School of China University of Mining and Technology (Beijing) and their supervisor, Baogui Yang, for their guidance, sampling assistance, encouragement, and continued participation in this work. This work was supported by the Filled Mining Laboratory Research Center of China University of Mining and Technology (Beijing).

Compliance of ethical standards

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- Bian, Z., Dong, J., Lei, S., Leng, H., Mu, S., Wang, H., 2009. The impact of disposal and treatment of coal mining wastes on environment and farmland. Environ Geol 58, 625–634. [CrossRef]

- Chandel, S., Singh, S.N., Seshadri, V., 2009. Deposition characteristics of coal ash slurries at higher concentrations. Advanced Powder Technology 20, 383–389. [CrossRef]

- Conte, T., Chaouche, M., 2019. Parallel superposition rheology of cement pastes. Cement and Concrete Composites 104, 103393. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L., Fall, M., 2015. A coupled thermo–hydro-mechanical–chemical model for underground cemented tailings backfill. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 50, 396–414. [CrossRef]

- Dzuy, N.Q., Boger, D.V., 1983. Yield Stress Measurement for Concentrated Suspensions. Journal of Rheology 27, 321–349. [CrossRef]

- Ferraris, C.F., Obla, K.H., Hill, R., 2001. The influence of mineral admixtures on the rheology of cement paste and concrete. Cement and Concrete Research 31, 245–255. [CrossRef]

- Haiqiang, J., Fall, M., Cui, L., 2016. Yield stress of cemented paste backfill in sub-zero environments: Experimental results. Minerals Engineering 92, 141–150. [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, S., 2000. Effective use of fly ash slurry as fill material. Journal of Hazardous Materials 76, 301–337. [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, D.R., Sato, K., Toyota, T., Funatsu, K., Tomita, Y., 2005. Effect of particle size distribution on pressure drop and concentration profile in pipeline flow of highly concentrated slurry. International Journal of Multiphase Flow 31, 809–823. [CrossRef]

- Klein, K., Simon, D., 2006. Effect of specimen composition on the strength development in cemented paste backfill. Can. Geotech. J. 43, 310–324. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, U., Mishra, R., Singh, S.N., Seshadri, V., 2003. Effect of particle gradation on flow characteristics of ash disposal pipelines. Powder Technology 132, 39–51. [CrossRef]

- Panchal, S., Deb, D., Sreenivas, T., 2018. Variability in rheology of cemented paste backfill with hydration age, binder and superplasticizer dosages. Advanced Powder Technology 29, 2211–2220. [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.H., Chaouche, M., Moranville, M., 2006. Influence of organic admixtures on the rheological behaviour of cement pastes. Cement and Concrete Research 36, 1807–1813. [CrossRef]

- Sivakugan, N., Rankine, R.M., Rankine, K.J., Rankine, K.S., 2006. Geotechnical considerations in mine backfilling in Australia. Journal of Cleaner Production 14, 1168–1175. [CrossRef]

- Sivakugan, N., Veenstra, R., Naguleswaran, N., 2015. Underground Mine Backfilling in Australia Using Paste Fills and Hydraulic Fills. Int. J. of Geosynth. and Ground Eng. 1, 18. [CrossRef]

- Szczepanska, J., Twardowska, I., 1999. Distribution and environmental impact of coal-mining wastes in Upper Silesia, Poland. Environmental Geology 38, 249–258. [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.A., Saak, A.W., Jennings, H.M., 1999. The influence of mixing on the rheology of fresh cement paste. Cement and Concrete Research 29, 1491–1496. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D., Deng, T., Zhao, R., 2018. A coupled THMC modeling application of cemented coal gangue-fly ash backfill. Construction and Building Materials 158, 326–336. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D., Hou, Y., Deng, T., Chen, Y., Zhao, X., 2017. Thermal, hydraulic and mechanical performances of cemented coal gangue-fly ash backfill. International Journal of Mineral Processing 162, 12–18. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D., Yang, B., Liu, Y., 2015a. Pressure drop in loop pipe flow of fresh cemented coal gangue–fly ash slurry: Experiment and simulation. Advanced Powder Technology 26, 920–927. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D., Yang, B., Liu, Y., 2015b. Transportability and pressure drop of fresh cemented coal gangue-fly ash backfill (CGFB) slurry in pipe loop. Powder Technology 284, 218–224. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Yang, B., Yu, M., 2019. Pressure Study on Pipe Transportation Associated with Cemented Coal Gangue Fly-Ash Backfill Slurry. Applied Sciences 9, 512. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W., Yu, G., Tan, S.K., Wang, H., 2014. Rheological properties of dense natural cohesive sediments subject to shear loadings. International Journal of Sediment Research 29, 454–470. [CrossRef]

- Zha, J., Guo, G., Feng, W., Wang, Q., 2011. Mining subsidence control by solid backfilling under buildings. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 21, s670–s674. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N., Zhang, J., Ouyang, S., Deng, X., Dong, C., Du, E., 2020. Feasibility study and performance optimization of sand-based cemented paste backfill materials. Journal of Cleaner Production 259, 120798. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q., Glasser, F.P., 2001. Thermal stability and decomposition mechanisms of ettringite at <120°C. Cement and Concrete Research 31, 1333–1339. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).