Submitted:

05 July 2023

Posted:

07 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study design

2.2. Surgical management

2.3. Statistical Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jehovah’s Witnesses. Why Don't Jehovah's Witnesses Accept Blood Transfusions? Available online:. Available online: https://www.jw.org/en/jehovahs-witnesses/faq/jehovahs-witnesses-why-no-blood-transfusions/ (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Chae, C.; Okocha, O.; Sweitzer, B. Preoperative considerations for Jehovah's Witness patients: a clinical guide. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2020, 33, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharman, C.D.; Burger, D.; Shatzel, J.J.; Kim, E.; DeLoughery, T.G. Treatment of individuals who cannot receive blood products for religious or other reasons. Am J Hematol 2017, 92, 1370–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, T.; Ralph, C. Perioperative Jehovah's Witnesses: a review. Br J Anaesth 2015, 115, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmers, P.A.; Speer, A.J. Clinical strategies in the medical care of Jehovah's Witnesses. Am J Med 2006, 119, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlikova, B.; van Dijk, J.P. Jehovah's Witnesses and Their Compliance with Regulations on Smoking and Blood Treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambault, A.L.; Brown, L.J.; Mellor, S.; Harky, A. Outcomes of cardiac surgery in Jehovah's Witness patients: A review. Perfusion 2021, 36, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, P. Treating Jehovah's Witnesses. Br J Perioper Nurs 2004, 14, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraca, R.J.; Wanamaker, K.M.; Bailey, S.H.; McGregor, W.E.; Benckart, D.H.; Maher, T.D.; Magovern, G.J., Jr. Strategies and outcomes of cardiac surgery in Jehovah's Witnesses. J Card Surg 2011, 26, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, E.P.; DeSimone, R.A. Transfusion support and alternatives for Jehovah's Witness patients. Curr Opin Hematol 2019, 26, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düsseldorf, K.E.d.U. Handlungsempfehlungen für die Behandlung von Zeugen Jehovas bei Bluttransfusionen. Available online: https://www.uniklinik-duesseldorf.de/fileadmin/Ausbildung_und_Karriere/KEK/Handlungsempfehlungen_fuer_den_Umgang_mit_Jehovas_Zeugen_Patienten_bei_geplanter_oder_unvorhergesehener_Bluttransfusion.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Jehovah’s Witnesses. How Many of Jehovah’s Witnesses Are There Worldwide? Available online:. Available online: https://www.jw.org/en/jehovahs-witnesses/faq/how-many-jw/ (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Müller, H.; Ratschiller, T.; Schimetta, W.; Meier, J.; Gombotz, H.; Zierer, A. Open Heart Surgery in Jehovah's Witnesses: A Propensity Score Analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 2020, 109, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauthy, P.; Pierrakos, C.; Chebli, L.; Tortora, R. Long-term survival and quality of life in Jehovah's witnesses after cardiac surgery: a case control study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2019, 19, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinakis, S.; Van der Linden, P.; Tortora, R.; Massaut, J.; Pierrakos, C.; Wauthy, P. Outcomes from cardiac surgery in Jehovah's witness patients: experience over twenty-one years. J Cardiothorac Surg 2016, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmert, M.Y.; Salzberg, S.P.; Theusinger, O.M.; Felix, C.; Plass, A.; Hoerstrup, S.P.; Falk, V.; Gruenenfelder, J. How good patient blood management leads to excellent outcomes in Jehovah's witness patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011, 12, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boer, C.; Meesters, M.I.; Milojevic, M.; Benedetto, U.; Bolliger, D.; von Heymann, C.; Jeppsson, A.; Koster, A.; Osnabrugge, R.L.; Ranucci, M.; et al. 2017 EACTS/EACTA Guidelines on patient blood management for adult cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2018, 32, 88–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.; Lee, M.; Kang, Y.; Cho, S.H. Patient blood management when blood is not an option: a report of two cases. Ann Palliat Med 2022, 11, 2768–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shander, A.; Goodnough, L.T. Management of anemia in patients who decline blood transfusion. Am J Hematol 2018, 93, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Ota, T.; Uriel, N.; Asfaw, Z.; Onsager, D.; Lonchyna, V.A.; Jeevanandam, V. Cardiovascular surgery in Jehovah's Witness patients: The role of preoperative optimization. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015, 150, 976–983.e971-973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Tempe, D.K. Anemia and Patient Blood Management in Cardiac Surgery-Literature Review and Current Evidence. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2018, 32, 2726–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanni, G.; Vitolo, M.; Imberti, J.F.; Girolami, D.; Bonini, N.; Valenti, A.C.; Cimato, P.; Boriani, G. Short and long-term outcomes after cardiac surgery in Jehovah's Witnesses patients: a case-control study. Intern Emerg Med 2022. [CrossRef]

- Jassar, A.S.; Ford, P.A.; Haber, H.L.; Isidro, A.; Swain, J.D.; Bavaria, J.E.; Bridges, C.R. Cardiac surgery in Jehovah's Witness patients: ten-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2012, 93, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamou, S.C.; White, T.; Barnett, S.; Boyce, S.W.; Corso, P.J.; Lefrak, E.A. Comparisons of cardiac surgery outcomes in Jehovah's versus Non-Jehovah's Witnesses. Am J Cardiol 2006, 98, 1223–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasques, F.; Kinnunen, E.M.; Pol, M.; Mariscalco, G.; Onorati, F.; Biancari, F. Outcome of Jehovah's Witnesses after adult cardiac surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Transfusion 2016, 56, 2146–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, B.; Jack, R.K.; Mullany, D.; Fraser, J. Comparison of outcome in Jehovah's Witness patients in cardiac surgery: an Australian experience. Heart Lung Circ 2010, 19, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlot, E.A.; Verwijmeren, L.; van de Garde, E.M.W.; Kloppenburg, G.T.L.; van Dongen, E.P.A.; Noordzij, P.G. Intra-operative red blood cell transfusion and mortality after cardiac surgery. BMC Anesthesiol 2019, 19, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenith, T.; Sharples, L.; Gerrard, C.; Valchanov, K.; Vuylsteke, A. Survival and length of stay following blood transfusion in octogenarians following cardiac surgery. Anaesthesia 2010, 65, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, K.A.; Acker, M.A.; Chang, H.; Bagiella, E.; Smith, P.K.; Iribarne, A.; Kron, I.L.; Lackner, P.; Argenziano, M.; Ascheim, D.D.; et al. Blood transfusion and infection after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2013, 95, 2194–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrainwala, Z.S.; Grega, M.A.; Hogue, C.W.; Baumgartner, W.A.; Selnes, O.A.; McKhann, G.M.; Gottesman, R.F. Intraoperative hemoglobin levels and transfusion independently predict stroke after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg 2011, 91, 1113–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, T.; Koch, C.G.; Xu, M.; Li, L.; Mihaljevic, T.; Figueroa, P.; Blackstone, E.H. Platelet transfusion in cardiac surgery does not confer increased risk for adverse morbid outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg 2008, 86, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.M.; Sikorski, R.A.; Konig, G.; Tsilimigras, D.I.; Hartmann, J.; Popovsky, M.A.; Pawlik, T.M.; Waters, J.H. Clinical Utility of Autologous Salvaged Blood: a Review. J Gastrointest Surg 2020, 24, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, M.F.; Hofmann, A.; Towler, S.; Trentino, K.M.; Burrows, S.A.; Swain, S.G.; Hamdorf, J.; Gallagher, T.; Koay, A.; Geelhoed, G.C.; et al. Improved outcomes and reduced costs associated with a health-system-wide patient blood management program: a retrospective observational study in four major adult tertiary-care hospitals. Transfusion 2017, 57, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazer, C.D.; Whitlock, R.P.; Fergusson, D.A.; Hall, J.; Belley-Cote, E.; Connolly, K.; Khanykin, B.; Gregory, A.J.; de Médicis, É.; McGuinness, S.; et al. Restrictive or Liberal Red-Cell Transfusion for Cardiac Surgery. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 2133–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, M.; Kromah, F.; Cooper, C. Blood transfusion and alternatives in Jehovah's Witness patients. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2021, 34, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| JW n=32 |

NW n>20,000 |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | years | 68.1 ± 9.4 | 67.6 ± 10.0 | 0.786 |

| Gender | male | 53.1% (17) | 72.4% (17571) | 0.015 |

| Height | cm | 169 ± 9 | 171 ± 9 | 0.200 |

| Weight | kg | 76 ± 14 | 83 ± 16 | 0.011 |

| BMI | kg/m2 | 26.43 ± 4.73 | 28.50 ± 4.82 | 0.005 |

| BSA | m2 | 1.88 ± 0.21 | 1.81 ± 0.59 | 0.510 |

| log ES | % | 10.25 ± 14.89 | 10.50 ± 14.79 | 0.293 |

| Emergency | 9.4% (3) | 9.2% (2236) | 0.976 | |

| Redo | 6.7% (2) | 4.4% (1072) | 0.549 |

| JW n=32 |

NW n=64 |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | years | 68.1 ± 9.4 | 67.4 ± 9.6 | 0.735 |

| Gender | male | 53.1% (17) | 57.8% (37) | 0.663 |

| Height | cm | 168 ± 9 | 168 ± 12 | 0.995 |

| Weight | kg | 76 ± 14 | 77 ± 15 | 0.772 |

| BMI | kg/m2 | 26.84 ± 4.79 | 27.16 ± 4.59 | 0.746 |

| BSA | m2 | 1.86 ± 0.19 | 1.87 ± 0.23 | 0.811 |

| log ES | % | 10.18 ± 14.91 | 8.07 ± 10.92 | 0.214 |

| ES II | % | 7.59 ± 15.97 | 5.30 ± 11.24 | 0.087 |

| LVEF preop | % | 56 ± 11 | 57 ± 11 | 0.749 |

| Emergency | 9.4% (3) | 6.3% (4) | 0.579 | |

| Redo surgery | 6.3% (2) | 7.8% (5) | 0.781 | |

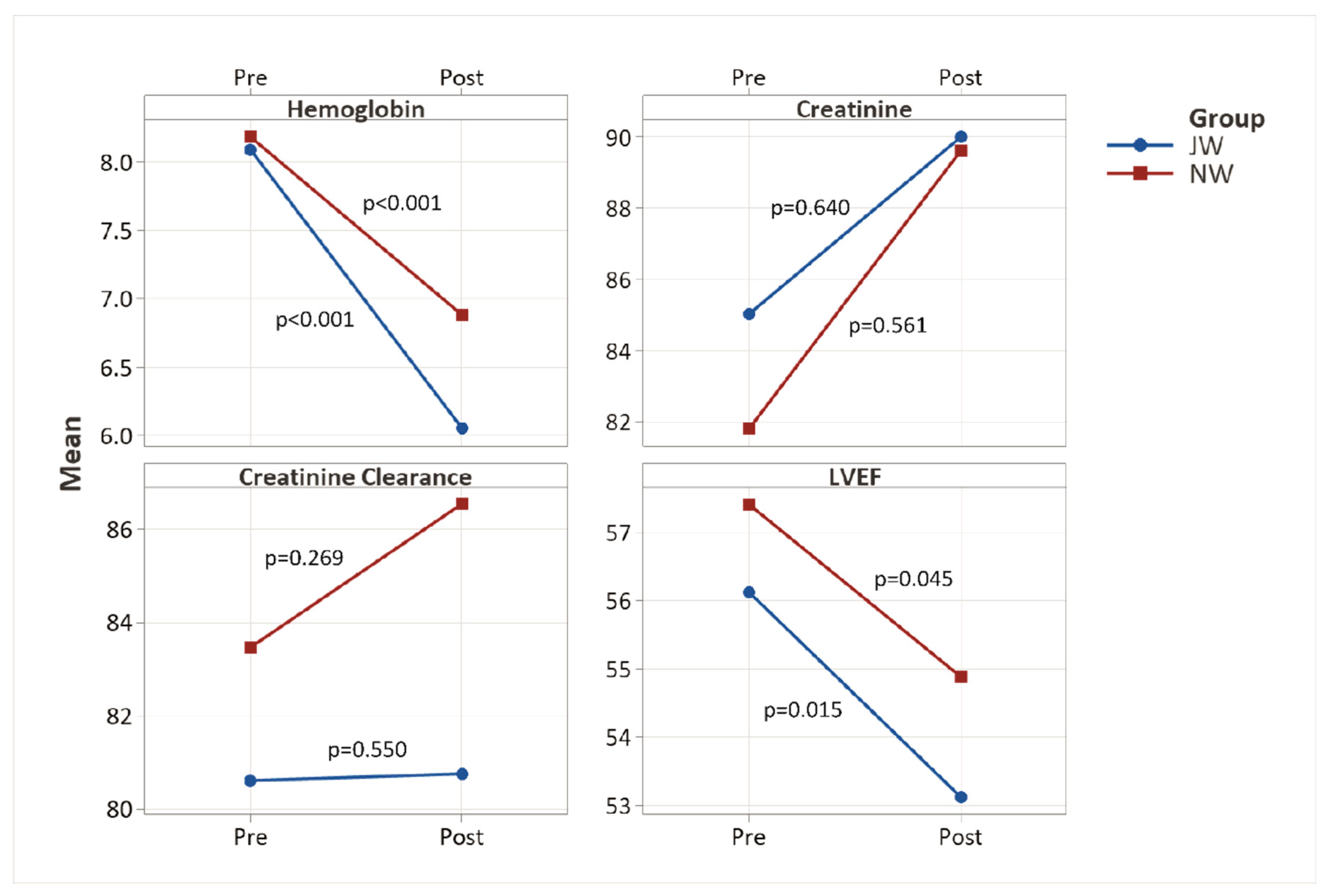

| Hemoglobin | mmol/l | 8.09 ± 0.99 | 8.18 ± 1.06 | 0.683 |

| g/dl | 13.04 ± 1.60 | 13.18 ± 1.71 | ||

| Hematocrit | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 0.645 | |

| Creatinine | µmol/l | 85.0 ± 21.6 | 81.8 ± 18.6 | 0.452 |

| Crea Clearance | ml/min | 80.6 ± 39.7 | 83.5 ± 31.9 | 0.499 |

| Endocarditis | 12.5% (4) | 3.1% (2) | 0.074 | |

| Malignant disease | 3.1% (1) | 4.7% (3) | 0.718 | |

| Arterial hypertension | 59.4% (19) | 78.1% (50) | 0.054 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 50.0% (16) | 46.9% (30) | 0.773 | |

| Smoking history | 3.1% (1) | 14.1% (9) | 0.098 | |

| NIDDM | 12.5% (4) | 25.0% (16) | 0.155 | |

| IDDM | 9.4% (3) | 9.4% (6) | 1.000 | |

| Stroke | 3.1% (1) | 1.6% (1) | 0.613 | |

| PVD | 6.3% (2) | 10.9% (7) | 0.458 | |

| CVD | 3.1% (1) | 3.1% (2) | 1.000 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 9.4% (3) | 25.0% (16) | 0.070 | |

| COPD | 9.4% (3) | 9.4% (6) | 1.000 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 25.0% (8) | 10.9% (7) | 0.074 | |

| Pacemaker | 3.1% (1) | 6.3% (4) | 0.516 |

| JW n=32 |

NW n=64 |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative EPO | 34.4% (11) | 0.0% (0) | 0.006 | |

| Valve surgery | 56.3% (18) | 48.4% (31) | 0.470 | |

| CABG | 56.3% (18) | 67.2% (43) | 0.294 | |

| Ascending aorta | 15.6% (5) | 4.7% (3) | 0.068 | |

| Aortic arch | 6.3% (2) | 1.6% (1) | 0.213 | |

| Other cardiac procedures | 9.4% (3) | 10.9% (7) | 0.813 | |

| Temperature | °C | 34.1 ± 3.3 | 34.3 ± 3.0 | 0.444 |

| Duration of surgery | min | 226 ± 74 | 227 ± 88 | 0.661 |

| ECC time | min | 132 ± 64 | 124 ± 60 | 0.341 |

| Clamp time | min | 81 ± 40 | 73 ± 32 | 0.159 |

| Total length of stay | hours | 20.8 ± 10.1 | 18.4 ± 8.2 | 0.343 |

| ICU length of stay | hours | 4.0 ± 6.5 | 3.0 ± 6.5 | 0.252 |

| Postop length of stay | hours | 16.4 ± 8.4 | 14.7 ± 7.5 | 0.351 |

| JW n=32 |

NW n=64 |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF postop | % | 53 ± 11 | 55 ± 11 | 0.521 |

| Hemoglobin | mmol/l | 6.05 ± 1.00 | 6.88 ± 0.87 | <0.001 |

| g/dl | 9.75 ± 1.61 | 11.09 ± 1.40 | ||

| Hematocrit | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 0.33 ± 0.04 | <0.001 | |

| Creatinine | µmol/l | 90.0 ± 41.3 | 89.6 ± 70.7 | 0.614 |

| Crea Clearance | ml/min | 80.8 ± 34.6 | 86.5 ± 38.2 | 0.603 |

| Red blood cell administration | units | 0.1 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 3.1 | <0.001 |

| Platelet administration | units | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.018 |

| Postoperative EPO | 15.6% (5) | 0.0% (0) | 0.001 | |

| Rethoracotomy (bleeding, tamponade) | 6.3% (2) | 6.3% (4) | 1.000 | |

| Pericardiocentesis | 6.3% (2) | 1.6% (1) | 0.213 | |

| New onset atrial fibrillation | 12.5% (4) | 21.9% (14) | 0.267 | |

| New pacemaker | 6.3% (2) | 0.0% (0) | 0.043 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.0% (0) | 1.6% (1) | 0.477 | |

| Wound healing disorders | 6.3% (2) | 7.8% (5) | 0.781 | |

| New onset dialysis | 9.4% (3) | 3.1% (2) | 0.194 | |

| Pneumonia | 6.3% (2) | 0.0% (0) | 0.043 | |

| Tracheostomy | 6.3% (2) | 3.1% (2) | 0.470 | |

| Septicemia | 0.0% (0) | 3.1% (2) | 0.312 | |

| Stroke | 0.0% (0) | 1.6% (1) | 0.477 | |

| Delirium | 18.8% (6) | 20.3% (13) | 0.856 | |

| Early Mortality | 6.3% (2) | 4.7% (3) | 0.745 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).