1. Introduction

Childhood and adolescence are developmental stages in which health habits and the regulation of emotional well-being are essential for an appropriate balance of mental health [

1,

2]. Health habits in children and adolescents are considered the set of learned behaviors that provide physical, cognitive and emotional wellbeing to the individual once they become habits [

3]. Some authors therefore have suggested that these health habits are closely related to emotional regulation, which is understood as the higher cognitive mechanisms and processes mainly executive, which we activate whenever an emotional response arises [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Previous studies state sleep as one of the main indicators in health habits and its association with cognitive-emotional variables [

8,

9]. Sleep habits seem to play an important role in the proper maturation of the brain during childhood and early adolescence [

10], and several studies have stated the relevance of the connection between the modulation of some cognitive processes and sleep disturbances [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. These cognitive processes take part of the executive functions (EF), which can be influenced by changes in sleep habits, causing some attentional and memory difficulties, mood fluctuations, behavioral problems and decreased school performance in youngsters [

16]. Moreover, upon the outbreak of the COVID19 pandemic, the number of children and adolescents presenting emotional and behavioral problems has significantly increased [

17]. These emotional and behavioral problems in youngsters tend to appear since they are six years old and they are associated with difficulties in emotion regulation strategies [

18].

Emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility are also the dimensions of the EF that have been most commonly related to sleep [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Impairments in executive functions are related to emotional and behavioral problems, and this may contribute towards the maintenance of emotional disorders [

26].

Additionally, previous investigations demonstrate the association of sleep disturbances and dimensions of EF, such as emotional regulation [

27,

28,

29] and cognitive flexibility [

30,

31] with the anxiety [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. According to recent research, all these associations may be explained due to the fact that executive disorders appear to be triggers of anxiety [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Thus, as previously mentioned, anxiety can potentially impact on the sleep habits of children and adolescents [

41,

42].

Many recent researchers have focused their interest on exploring how sleep problems negatively influence emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility [

43,

44]. Some of them have fixed their attention on investigating the bidirectional correlation between sleep habits and emotional regulation [

43,

44], whereas others have observed the influence of emotional regulation on health habits such as sleep [

45,

46]. We hypothesized that the alteration of the processes and functions of the executive system may be a predictor of sleep habits, and anxiety as a mediator of this relationship. Given the aforementioned, the current study aimed: (1) to analyze the correlations among sleep habits, anxiety and executive functioning, including its dimensions (emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility), (2) to determine the influence of emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility on sleep habits; and (3) explore the mediating role of anxiety between executive functioning and sleep habits.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study population and design

The present research was a cross-sectional correlational and explicative study. The sample consisted of the initial sample was comprised of 953 children and adolescents, of which 953 (512 males and 441 females) finally participated, with ages between 6 and 18 years (M = 10.85; DT = 3.29). The sample was recruited after sending telematic questionnaires, residing in Spain. The collaboration of the legal guardians was required, with them answering the questionnaires in relation to children’s information. Of these, 804 were females and 149 males, aged between 19 and 68 years (M = 43.30; DT = 6.70). All the legal guardians were aware of the different phases and characteristics of the study, signed the informed consent and completed the questionnaire. In the case of people over 18, they could sign the informed consent and complete the questionnaire themselves. Those who did not fully complete the questionnaire or did not provide the informed consent were excluded from the study. The nationality of the respondents was mostly Spanish (95.9%). The relationship that these people have with the child or adolescent in 84.6% is maternal, in 12.9% paternal, in 1.5% of siblings and the rest with percentages of 1%, other relationships such as grandparents, uncles, neighbors’ and/or guardians.

2.2. Instruments

Recipients rated their children’s anxiety using the Spanish version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) test [

47,

48]. This test also demonstrated adequate psychometric properties [

49]. The STAIC was composed of 40 items which are equally divided in two main dimensions: trait and state anxiety. The state anxiety scale tried to clarify “how the child feels at a given moment”. The trait anxiety scale measured “how the child feels in general,” exploring relatively stable differences in propensity to anxiety. Parents answered the questionnaire with their children’s information for the current study. Original items were modified by including “Your child…” at the beginning of each item. For instance: “your child feels calm”, “your child feels restless”. Response options were 7-point Likert scales, in which 1 = “strongly disagree” and 7 = “strongly agree”. For this study, the reliability of the instrument was adequate, presenting values of α=0.894 for trait anxiety; and α=0.907 for state anxiety.

BEARS was used as a brief sleep habits disturbances screening test with 9 items [

50]. This test was completed by parents/guardians answering questions such as “their child seems to be tired or drowsy” or “their child wakes up several times during the night”. Each item had 7 response options, in which 1 = totally disagree and 7 = totally agree. Regarding the reliability and internal consistency, the scale presented a Cronbach alpha's coefficient of 0.732 [

51].

The BRIEF-2 (parent-report form) test was used to assess executive behavior [

52]. It consisted of nine scales made up of 63 items with three possible response options (always, sometimes or never). From these domains, ten items of the emotional regulation subscale were selected, which included emotional control and cognitive flexibility as dimensions. It was decided to carry out a brief screening selecting these items of the parent version since they were directly related to the objectives of the present study. Six of these items of emotional control, and four items of cognitive flexibility were used. For the present sample, these items showed adequate reliability through Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients: α=0.902, ω=0.901 for the emotional regulation subscale, α=0.877, ω=0.881 for emotional control, and α=0.832, ω=0.830 for cognitive flexibility

2.3. Procedure

The current study was authorized by the ethics committee of the University of Alicante. Families were informed about the objectives of the study and researchers indicated that participation was completely confidential, anonymous, and voluntary. Parents who agreed to participate in the study were sent a link to the evaluation protocol configured on the Google Form platform. Participation in the study was requested through social media groups, using a snowball sampling strategy. To protect the confidentiality and anonymity of the data, codes were assigned to identify the participants following a pseudonymization process. The research was conducted following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the European Union of Good Clinical Practice Standards.

2.4. Data analysis plan

Preliminary analyses. Prior to conducting the primary statistical analyses in line with the study’s aims, descriptive statistics (i.e., means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis) of participants’ trait/state anxiety, sleep habits, executive functions, emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility. To examine bivariate correlations among trait/state anxiety, sleep habits, executive functions, emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility, a correlation matrix was created. According to Hernández-Lalinde et al. [

53], the interpretation of the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) was: 0.00 < r < 0.10 for null correlations; 0.11 < r < 0.30 for weak correlations; 0.31 < r < 0.50 for moderate correlations; and 0.51 < r < 1.00 for strong correlations.

Hierarchical regression analyses. Four hierarchical regressions were run to examine the role of trait/state anxiety, and executive functions variables as predictors of sleep habits disturbances. In Model 1, trait anxiety was included as predictor. Model 2 included trait and state anxiety as predictors. Model 3 then included trait and state anxiety, and cognitive rigidity. And Model 4 included trait/state anxiety, cognitive rigidity, and emotional regulation as predictors.

Mediational models.

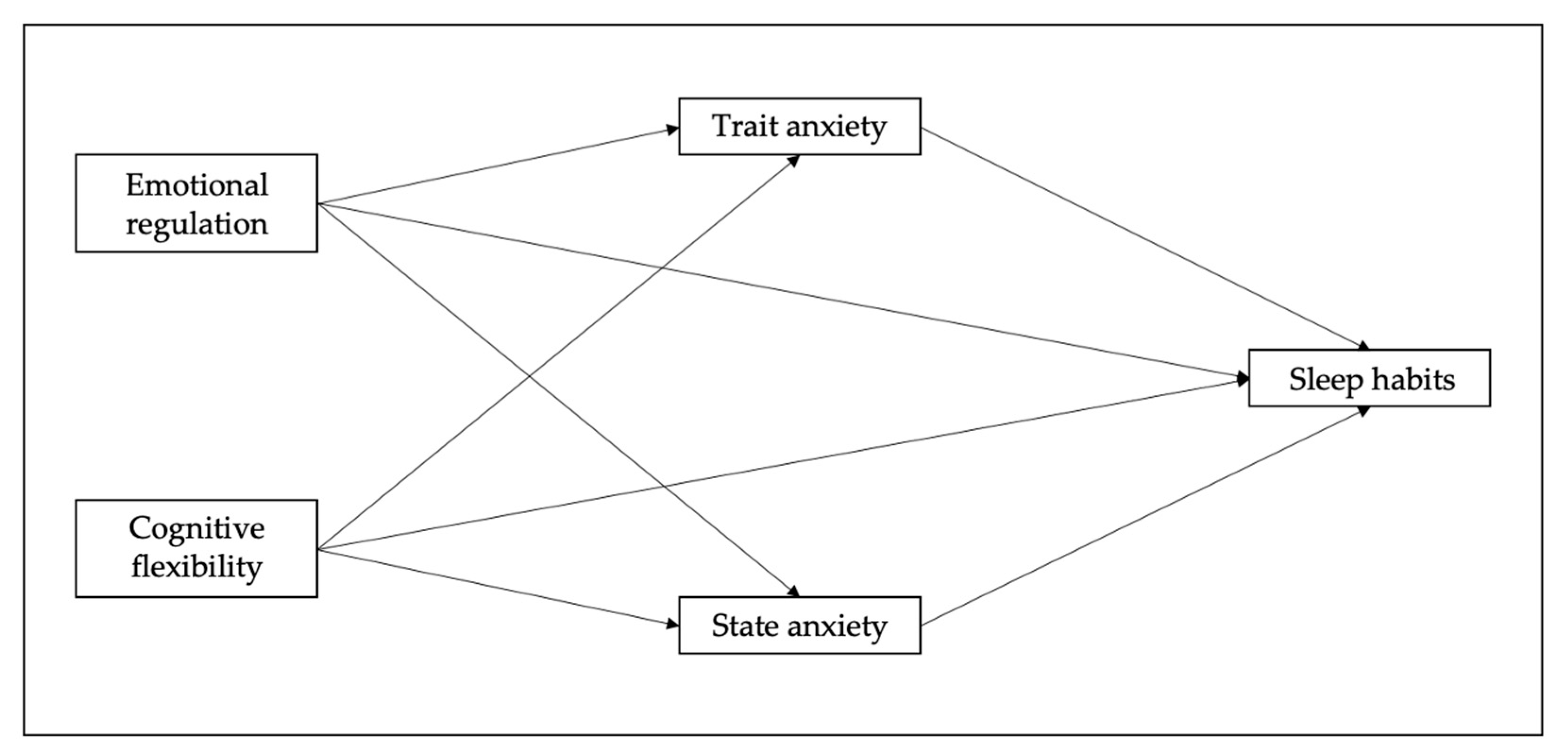

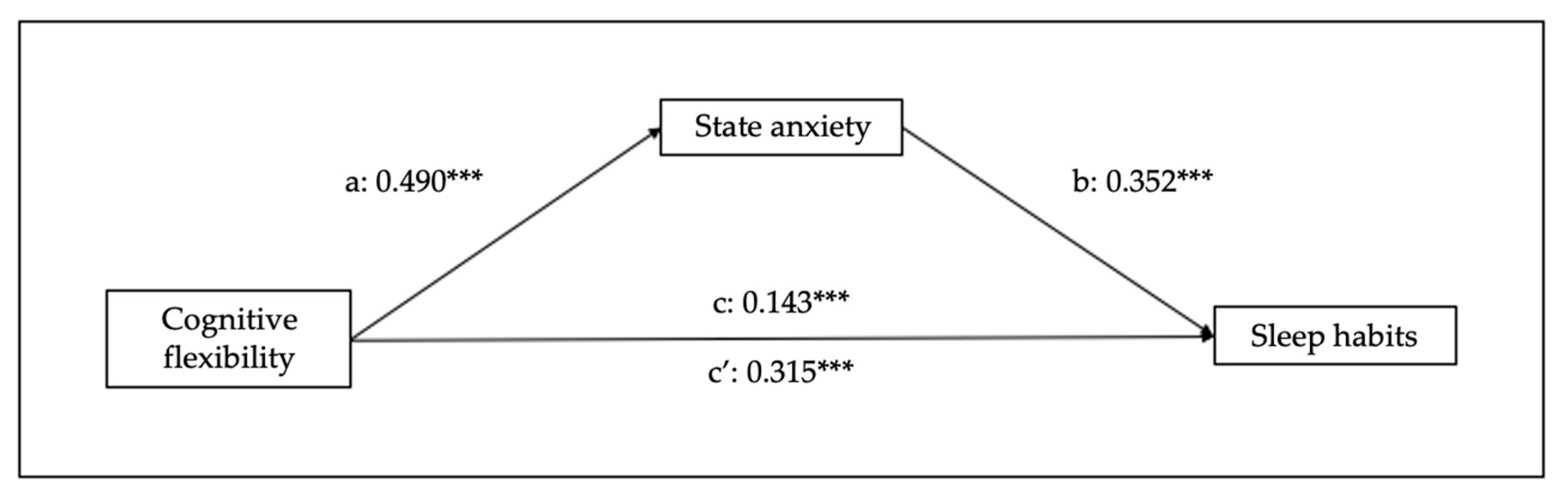

Figure 1 shows four mediational models, which were developed using the PROCESS macro [

54] to examine the direct and indirect effects of emotional regulation, cognitive flexibility on sleep habits, using 5,000 bootstrap samples. Bootstrapping is a non-parametric method for assessing indirect effects [

55,

56]. Bootstrapping provides the most powerful and reasonable method of obtaining confidence limits for specific indirect effects under most conditions [

57]. In the first two models, emotional regulation (model 1) and cognitive flexibility (model 2) were specified to lead to trait anxiety which was then specified to lead sleep habits. In the other two models, emotional regulation (model 3) and cognitive flexibility (model 4) were specified to lead to state anxiety which was then specified to lead sleep habits.

Analyses were performed using SPSS version 28.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and correlation analysis between trait and state anxiety, executive functions and sleep disturbances.

Table 1 shows the descriptive analysis results and the relationship among the study variables. Specifically, both state and trait anxiety demonstrate a positive, moderate and significant correlation with sleep habits disturbances. Moreover, state and trait anxiety are importantly associated with executive dysfunctions, especially, with emotional dysregulation and cognitive rigidity. Sleep habits disturbances have also pointed out positive, moderate and significant correlations with the executive dysfunctions global index, emotional dysregulation and cognitive rigidity (

Table 1).

3.2. State/trait anxiety, and executive dysfunctions as predictors of sleep habits disturbances.

Table 2 shows the regression models in which trait/state anxiety, emotional dysregulation, and cognitive rigidity are considered as predictors of sleep habits disturbances. Although cognitive rigidity appears to be a significant predictor of sleep habits disturbances, that variable is not significant when emotional dysregulation is introduced in the regression model. Trait/state anxiety remains as a significant predictor of sleep habits disturbances in all models.

3.3. The mediating role of the anxiety between executive functions and sleep disturbances.

Four mediational models were built to explore the mediation effects of anxiety in the relationship between executive functioning dimensions (emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility) and sleep habits, controlling children’s age, parents’ marital status, and parents’ educational level. Emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility have been entered in the model as independent variables, trait/state anxiety as mediators, and sleep habits have been evaluated as a dependent variable.

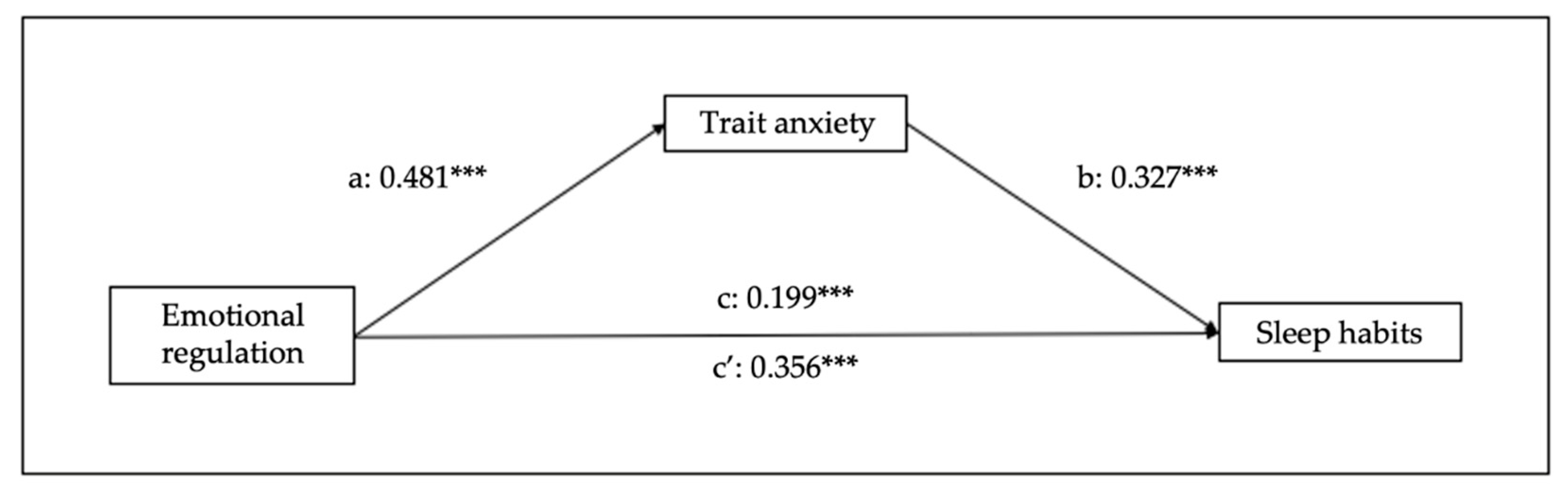

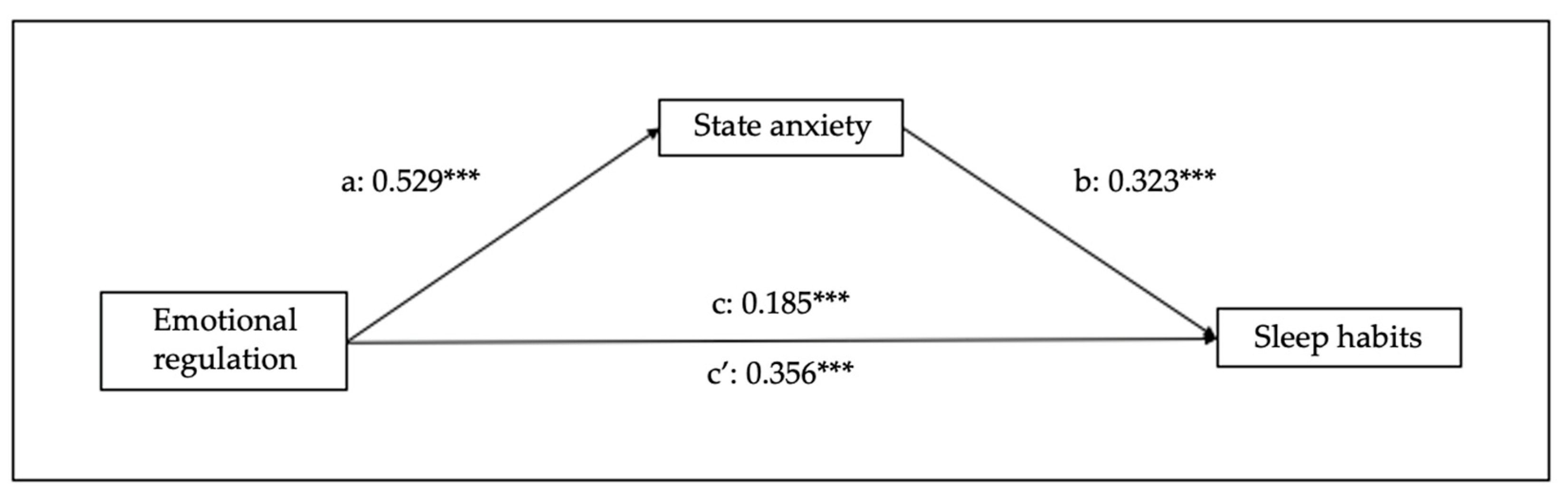

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show the mediational effects of trait/state anxiety, in which emotional regulation predicts sleep habits (B=0.143, SE=0.013, 95% CI [0.03-0.08], p<0.001), trait anxiety (B=0.481, SE=0.021, 95% CI [0.32-0.40], p<0.001), and state anxiety (B=0.529, SE=0.024, 95% CI [0.41-0.51], p<0.001). Regarding the mediation variables, sleep habits are predicted by trait (B=0.224, SE=0.019, 95% CI [0.07-0.15], p<0.001) and state (B=0.199, SE=0.017, 95% CI [0.05-0.12], p<0.001) anxiety. Moreover, the analyses of the indirect effect of trait and state anxiety show significant mediations (indirect effect of trait anxiety: B=0.107, SE=0.019, 95% CI [0.07-0.15], p<0.001); indirect effect of state anxiety: B=0.106, SE=0.021, 95% CI [0.07-0.15], p<0.001).

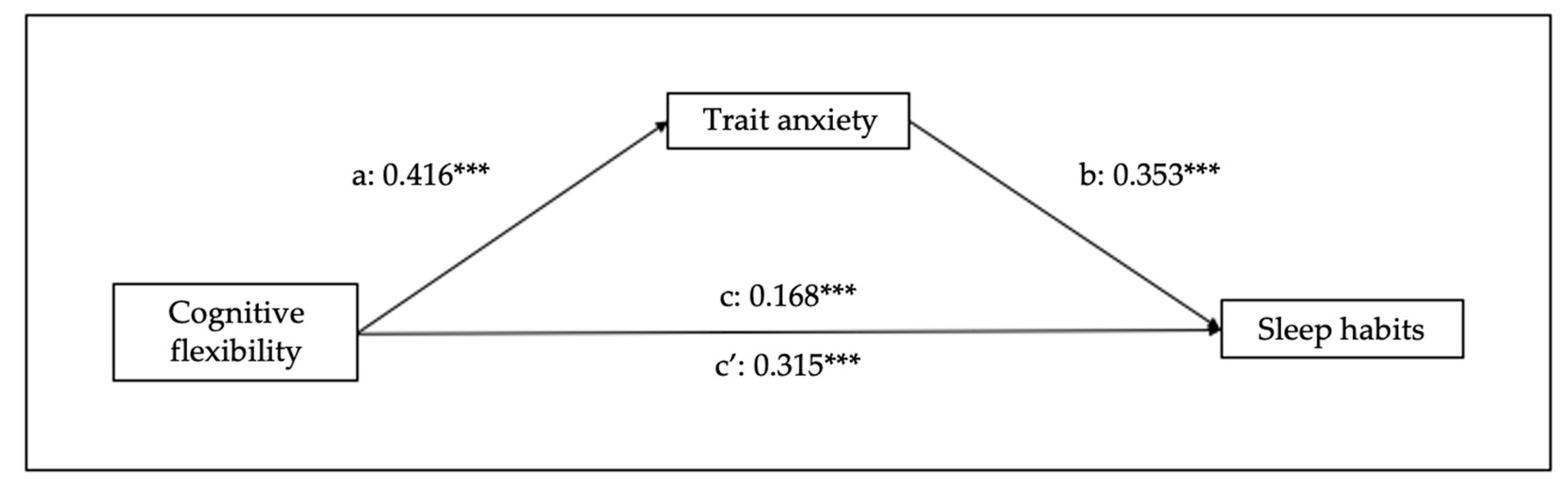

Finally, in relation to the other mediational models, cognitive flexibility predicts sleep habits (B=0.190, SE=0.019, 95% CI [0.15-0.23], p<0.001), trait anxiety (B=0.473, SE=0.037, 95% CI [0.40-0.54], p<0.001), and state anxiety (B=0.668, SE=0.041, 95% CI[0.59-0.75], p<0.001). Regarding the mediation variables, sleep habits are predicted by trait (B=0.213, SE=0.015, 95% CI [0.18-0.24], p<0.001) and state (B=0.178, SE=0.013, 95% CI [0.15-0.20], p<0.001) anxiety. Moreover, the analysis of the indirect effect of trait and state anxiety show significant mediations (indirect effect of trait anxiety: B=0.082, SE=0.01, 95% CI [0.06-0.10], p<0.001); indirect effect of state anxiety: B=0.096, SE=0.012, 95% CI [0.07-0.12], p<0.001) (see

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

Sleep and executive functions are influenced by child development factors. Several researchers have assessed the effect of sleep on EF, especially, the management of emotions. However, there is a scarce number of studies focusing on the impact of emotional regulation on sleep habits. The present study aimed to analyze the influence of EF (emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility) on the sleep habits, considering the mediating role of trait/state anxiety in children and adolescents through the parents’ perception. We therefore set the following objectives: (1) analyzing the relationship among sleep habits, trait/state anxiety, and EF (emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility); (2) exploring the influence of the trait/state anxiety, the emotional regulation and the cognitive flexibility on the sleep habits; and (3) examining the mediating role of state/trait anxiety in the relationship between the EF (emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility) and sleep habits.

In respect of the relationship among the variables measured, findings revealed moderate-strong and positive correlations. That is, the higher trait/state anxiety, the higher sleep habits disturbances and alterations in EF. These results are consistent with previous research studies, in which they highlighted that the increasing level of anxiety could be related to the appearance of sleep habits disturbances [

41,

42,

58]. It is known for a long time the relationship between these two variables. In fact, some studies have suggested that anxiety and sleep are strictly related and affect each other in a two-way manner [

59]. Moreover, other recent studies have stated the direct association of the levels of anxiety with alterations in emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Further, based on the results of previous scientific studies, sleep habits disturbances seem to be linked to a higher level of difficulty in controlling EF, especially, emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility [

20,

21,

22,

60].

Regarding the findings observed of the multiple regressions created, trait/state anxiety appear to be significant in all models. This is coherent with other investigations, in which they identified anxiety as a predictor of the fluctuation of sleep habits in children and adolescents [

41,

61]. Moreover, emotional regulation also showed an influence on sleep habits. As a matter of fact, recent literature has suggested further consideration of the management of emotions to fully understand sleep habits [

22,

44]. Furthermore, the results have demonstrated the importance of the mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between EF (emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility) and sleep habits. These findings are also consistent with other research studies, in which anxiety has played an essential role in this relationship measured [

34,

35]. Previous studies from different countries have supported the association between sleep and emotional problems in children [

62]. It has been also indicated that children may present different sleep problems associated with emotional problems [

63,

64].

5. Strength, limitations, and future research

The current study's findings could help the scientific and clinical community further understand the need to examine the mechanisms associated with the relationship between emotional regulation and sleep habits. These results also allow professionals and the rest of society to identify and prevent sleep disturbances related to maladaptive emotional strategies. However, although this research comprises a great sample of participants and rich data analysis, which let us explain the performance of the variables measured, it is not without limitations that we are aware of. This study was carried out from the perspective of parents. As the questionnaires were sent via social networks to parents, despite parental observation being known as one the most reliable methods to assess children’s behaviors, that could be a reason for some biases for the results [

65,

66]. Measures are vulnerable to recall bias and findings should be therefore interpreted with caution.

In regard to the BEARS, although it is a suitable data source for sleep habits, which contains some validated measures, it does not include all the dimensions we would have liked to explore. For example, information on sleep quality, such as subjective sleep quality or possible pharmacological treatments for altered sleep quality were not available. This could differentiate the sleep habits and quality.

As for the future research lines, it is essential to carry out investigations in which children are the direct participants. This could avoid some difficulties in exploring their behavior and parents’ biases. Additionally, analyzing the similarities and differences between sex or age groups would provide the scientific community with interesting data about the manifestation of the variables measured between males and females, and also across the age. Further, another crucial issue to deal with is to explore other protection and vulnerability factors of the sleep habits through a latent variable analysis, in which other psychosocial factors could be considered to better understand children and adolescents’ behavior.

6. Conclusions

The present study sheds light on the significance of employing effective emotional regulation strategies and managing anxiety in order to promote healthy sleep habits. It is evident that higher levels of anxiety are associated with increased disruptions in the sleep patterns of children and adolescents, with anxiety and emotional regulation emerging as influential factors, as reported by parents. Furthermore, emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility can be considered protective factors for overall health habits, including sleep. In light of these findings, it is imperative for healthcare professionals to prioritize the identification and evaluation of potential sleep-related issues in children and adolescents. This is particularly crucial as anxiety-inducing environments, such as school, family, and work settings, can have detrimental effects on sleep habits and executive functioning. Therefore, it becomes essential to enhance the utilization of emotional and cognitive strategies to facilitate the regulation of sleep habits effectively.

It is important to recognize that the promotion of adequate sleep habits is a multidimensional task that requires a comprehensive approach. By addressing emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility, professionals can help individuals develop the necessary skills to regulate their sleep patterns more effectively. This includes the identification of triggers that may disrupt sleep, the implementation of relaxation techniques, and the establishment of consistent bedtime routines. Additionally, providing education and support to parents and caregivers is vital in ensuring a conducive sleep environment and reinforcing positive sleep habits.

By integrating emotional and cognitive strategies into sleep interventions, the overall well-being and executive performance of children and adolescents can be significantly improved. The recognition of the intricate relationship between emotions, anxiety, and sleep habits underscores the need for a holistic approach that considers the interplay of various factors. Ultimately, fostering healthy sleep habits early on can have long-lasting benefits, contributing to optimal development and overall quality of life.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, B.C.-L., R.L.-C. and I.N.-S.; methodology, B.C.-L., R.L.-C. and I.N.-S.; formal analysis, B.C.-L.; investigation, B.C.-L., J.C.V., R.L.-C. and I.N.-S.; data curation, B.C.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, B.C.-L., J.C.V., R.L.-C. and I.N.-S.; writing—review and editing, B.C.-L., R.J.-R., R.L.-C. and I.N.-S.; supervision, R.L.-C. and I.N.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee and Vice-Rectorate for Research and Knowledge Transfer of the University of Alicante (UA-2020-05-12).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The availability of data must be personally requested to the corresponding author at ignasi.navarro@ua.es

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hamilton, K.; van Dongen, A.; Hagger, M.S. An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior for Parent-for-Child Health Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. Health Psychology 2020, 39, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da-Silva-Domingues, H.; del-Pino-Casado, R.; Palomino-Moral, P.Á.; López Martínez, C.; Moreno-Cámara, S.; Frías-Osuna, A. Relationship between Sense of Coherence and Health-Related Behaviours in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelman, C.; Kudzma, E.C. Health Promotion Throughout the Life Span, 2021 10th Edition. Available online: https://evolve.elsevier.com/cs/product/9780323761406?role=student.

- Mitler, M.; Dement, W.; Dinges, D. Sleep Medicine, Public Policy, and Public Health (2000). In Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine; 2000; pp. 580–588. ISBN 978-0-7216-7670-8. [Google Scholar]

- Luyster, F.S.; Strollo, P.J., Jr.; Zee, P.C.; Walsh, J.K. Sleep: A Health Imperative. Sleep 2012, 35, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandner, M.A. Sleep, Health, and Society. Sleep Medicine Clinics 2017, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramar, K.; Malhotra, R.K.; Carden, K.A.; Martin, J.L.; Abbasi-Feinberg, F.; Aurora, R.N.; Kapur, V.K.; Olson, E.J.; Rosen, C.L.; Rowley, J.A.; et al. Sleep Is Essential to Health: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Position Statement. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2021, 17, 2115–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, R.; Cole, R.; Ejikeme, C.; Orstad, S.L.; Porten, S.; Salter, C.A.; Sanchez Nolasco, T.; Vieira, D.; Loeb, S. Systematic Review of Sleep and Sleep Disorders among Prostate Cancer Patients and Caregivers: A Call to Action for Using Validated Sleep Assessments during Prostate Cancer Care. Sleep Medicine 2022, 94, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, J.S.; Cartwright, R.; Vernooij, R.W.M.; Aoki, Y.; Agarwal, A.; Mangera, A.; Markland, A.D.; Tsui, J.F.; Santti, H.; Griebling, T.L.; et al. The Impact of Nocturia on Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Urology 2020, 203, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F. Sleep and Early Brain Development. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 2020, 75, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Y.; Horne, J.A. Sleep Deprivation Affects Speech. Oxford Academic, 1997. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article/20/10/871/2725969 (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Randazzo, A.C.; Muehlbach, M.J.; Schweitzer, P.K.; Walsh, J.K. Cognitive Function Following Acute Sleep Restriction in Children Ages 10-14. Sleep 1998, 21, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Engleman, H.; Joffe, D. Neuropsychological Function in Obstructive Sleep Apnoea. Sleep Medicine Reviews 1999, 3, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.; Harrison, Y. Frontal Lobe Function, Sleep Loss and Fragmented Sleep. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2001, 5, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzur, A.; Pace-Schott, E.F.; Hobson, J.A. The Prefrontal Cortex in Sleep. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2002, 6, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, A.M.; Kivisto, L.R.; Deasley, S.; Casey, J.E. Executive Functioning Rating Scale as a Screening Tool for ADHD: Independent Validation of the BDEFS-CA. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2021. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1087054719869834.

- Fernandes, B.; Wright, M.; Essau, C.A. The Role of Emotion Regulation and Executive Functioning in the Intervention Outcome of Children with Emotional and Behavioural Problems. Children 2023, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldao, A.; Gee, D.G.; De Los Reyes, A.; Seager, I. Emotion Regulation as a Transdiagnostic Factor in the Development of Internalizing and Externalizing Psychopathology: Current and Future Directions. Dev Psychopathol 2016, 28, 927–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, R.C.; Ebesutani, C.; Olatunji, B.O. Linking Sleep Disturbance and Maladaptive Repetitive Thought: The Role of Executive Function. Cogn Ther Res 2016, 40, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, R.; Cassoff, J. The Interplay Between Sleep and Emotion Regulation: Conceptual Framework Empirical Evidence and Future Directions. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2014, 16, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairholme, C.P.; Manber, R. Sleep, Emotions, and Emotion Regulation. In Sleep and Affect; Elsevier, 2015; pp. 45–61. ISBN 978-0-12-417188-6. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, C.A.; Alfano, C.A. Sleep and Emotion Regulation: An Organizing, Integrative Review. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2017, 31, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaso, C. C.; Johnson, A. B.; Nelson, T. D. Effect of Sleep Deprivation and Restriction on Mood, Emotion, and Emotion Regulation: Three Meta-Analyses in One. Sleep 2021, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, L.K.; Cain, S.W.; Chang, A.-M.; Saxena, R.; Czeisler, C.A.; Anderson, C. Impaired Cognitive Flexibility during Sleep Deprivation among Carriers of the Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Val66Met Allele. Behavioural Brain Research 2018, 338, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honn, K.A.; Hinson, J.M.; Whitney, P.; Van Dongen, H.P.A. Cognitive Flexibility: A Distinct Element of Performance Impairment Due to Sleep Deprivation. Accident Analysis & Prevention 2019, 126, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, S.L.; Heller, W.; Miller, G.A. The Structure of Executive Dysfunction in Depression and Anxiety. J Affect Disord 2021, 279, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cisler, J.M.; Olatunji, B.O.; Feldner, M.T.; Forsyth, J.P. Emotion Regulation and the Anxiety Disorders: An Integrative Review. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2010, 32, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cisler, J.M.; Olatunji, B.O. Emotion Regulation and Anxiety Disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2012, 14, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, J.Ö.; Naumann, E.; Holmes, E.A.; Tuschen-Caffier, B.; Samson, A.C. Emotion Regulation Strategies in Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review. J Youth Adolescence 2017, 46, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Moghaddam, B. Impact of Anxiety on Prefrontal Cortex Encoding of Cognitive Flexibility. Neuroscience 2017, 345, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Lin, Y. Anxiety and Depression Aggravate Impulsiveness: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Cognitive Flexibility. Psychology, Health & Medicine 2020, 25, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, P. K.; Roberts, R. M.; Harris, J. K. Systematic Review Assessing Bidirectionality between Sleep Disturbances, Anxiety, and Depression. Sleep 2013, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, A.; Gunstad, J. Poor Sleep Quality Diminishes Cognitive Functioning Independent of Depression and Anxiety in Healthy Young Adults. The Clinical Neuropsychologist 2012, 26, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Soria, I.; Real-Fernández, M.; Juárez-Ruiz de Mier, R.; Costa-López, B.; Sánchez, M.; Lavigne, R. Consequences of Confinement Due to COVID-19 in Spain on Anxiety, Sleep and Executive Functioning of Children and Adolescents with ADHD. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavigne-Cerván, R.; Costa-López, B.; Juárez-Ruiz de Mier, R.; Real-Fernández, M.; Sánchez-Muñoz de León, M.; Navarro-Soria, I. Consequences of COVID-19 Confinement on Anxiety, Sleep and Executive Functions of Children and Adolescents in Spain. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Carbonell, L.; Meurling, I.J.; Wassermann, D.; Gnoni, V.; Leschziner, G.; Weighall, A.; Ellis, J.; Durrant, S.; Hare, A.; Steier, J.; et al. Impact of the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic on Sleep. Journal of Thoracic Disease 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, G. N.; Bezerra, A. G.; Tufik, S.; Andersen, M. L. Effects of Acute Sleep Deprivation on State Anxiety Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sleep 2016, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmer, A.J.; Gotlib, I.H. Switching and Backward Inhibition in Major Depressive Disorder: The Role of Rumination. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2012, 121, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredemeier, K.; Warren, S.L.; Berenbaum, H.; Miller, G.A.; Heller, W. Executive Function Deficits Associated with Current and Past Major Depressive Symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders 2016, 204, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madian, N.; Bredemeier, K.; Heller, W.; Miller, G. A.; Warren, S. L. Repetitive Negative Thought and Executive Dysfunction: An Interactive Pathway to Emotional Distress. Cognitive Therapy and Research 2019, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staner, L. Sleep and Anxiety Disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2003, 5, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, W.J.; Wilkerson, A.K.; Boyd, S.J.; Dewey, D.; Mesa, F.; Bunnell, B.E. A Review of Sleep Disturbance in Children and Adolescents with Anxiety. Journal of Sleep Research 2018, 27, e12635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, M.; Sheppes, G.; Sadeh, A. Sleep and Emotions: Bidirectional Links and Underlying Mechanisms. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2013, 89, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandekerckhove, M.; Wang, Y.; Vandekerckhove, M.; Wang, Y. Emotion, Emotion Regulation and Sleep: An Intimate Relationship. AIMSN 2018, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellappa, S.L.; Aeschbach, D. Sleep and Anxiety: From Mechanisms to Interventions. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2022, 61, 101583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sheikh, M.; Buckhalt, J.A. Vagal Regulation and Emotional Intensity Predict Children’s Sleep Problems. Developmental Psychobiology 2005, 46, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D. STAI: cuestionario de ansiedad estado-rasgo : manual / C.D. Spielberger, R.L. Gorsuch, R.E. Lushene; (Psicología aplicada. Serie menor; 6a ed.; TEA: Madrid, 2002; ISBN 978-84-7174-724-2. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Seisdedos Cubero, N.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.E. Cuestionario de ansiedad estado-rasgo: manual; TEA Ediciones, 1982; ISBN 978-84-7174-129-5. [Google Scholar]

- Guillén Riquelme, A.; Buela Casal, G. Actualización psicométrica y funcionamiento diferencial de los ítems en el State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Psicothema 2011, 23, 510–515. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, J.A.; Dalzell, V. Use of the “BEARS” Sleep Screening Tool in a Pediatric Residents’ Continuity Clinic: A Pilot Study. Sleep Med 2005, 6, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Vélez, R.; Huertas Zamora, L.; Correa Bautista, J.E.; Cárdenas Calderón, E.G. Confiabilidad y validez del cuestionario de trastornos de sueño BEARS en niños y adolescentes escolares de Bogotá, D.C., Colombia: Estudio FUPRECOL. Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación, 2018; 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, G.A.; Isquith, P.K.; Guy, S.C.; Kenworthy, L. Evaluación Conductual de la Función Ejecutiva. TEA Ediciones 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Lalinde, J.; Espinosa-Castro, J.-F.; Penaloza-Tarazona, M.-E.; Díaz-Camargo, É.; Bautista-Sandoval, M.; Riaño-Garzón, M.E.; Lizarazo, O.M.C.; Chaparro-Suárez, Y.K.; Álvarez, D.G.; Bermúdez-Pirela, V. Sobre El Uso Adecuado Del Coeficiente de Correlación de Pearson: Verificación de Supuestos Mediante Un Ejemplo Aplicado a Las Ciencias de La Salud. Archivos Venezolanos de Farmacología y Terapéutica 2018, 37, 552–561. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: Third Edition: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford publications 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behavior Research Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, K.H.; Waters, W.F.; Binks, P.G.; Anderson, T. Generalized Anxiety and Sleep Architecture: A Polysomnographic Investigation. Sleep 1997, 20, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearick-Silva, L.E.; Richter, S.A.; Viola, T.W.; Nunes, M.L. ; COVID-19 Sleep Research Group Sleep Quality among Parents and Their Children during COVID-19 Pandemic. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2022, 98, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, R.; Nielsen, T. Nightmares, Bad Dreams, and Emotion Dysregulation: A Review and New Neurocognitive Model of Dreaming. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2009, 18, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maqbali, M.; Al Sinani, M.; Al-Lenjawi, B. Prevalence of Stress, Depression, Anxiety and Sleep Disturbance among Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2021, 141, 110343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindell, J. A.; Sadeh, A.; Kwon, R.; Goh, D. Y. Cross-Cultural Differences in the Sleep of Preschool Children. Sleep Medicine 2013, 14, 1283–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Takahashi, M.; Wu, R.; Liu, Z.; Adachi, M.; Saito, M.; Nakamura, K.; Jiang, F. Association between Sleep Disturbances and Emotional/Behavioral Problems in Chinese and Japanese Preschoolers. Behavioral Sleep Medicine 2020, 18, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilter Bahadur, E.; Zengin Akkus, P.; Coskun, A.N.; Karabulut, E.; Ozmert, E.N. Sleep and Social–Emotional Problems in Preschool-Age Children with Developmental Delay. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 2022, 20, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.E.; Perkins, K.A.; Dai, Y.G.; Fein, D.A. Comparison of Parent Report and Direct Assessment of Child Skills in Toddlers. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 2017, 41–42, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo-Huertas, J.; Schafer, G. Agreement and Reliability of Parental Reports and Direct Screening of Developmental Outcomes in Toddlers at Risk. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).