Submitted:

05 July 2023

Posted:

06 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Procedures

2.3. Data Groups for Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Supplement Type and Prevalence

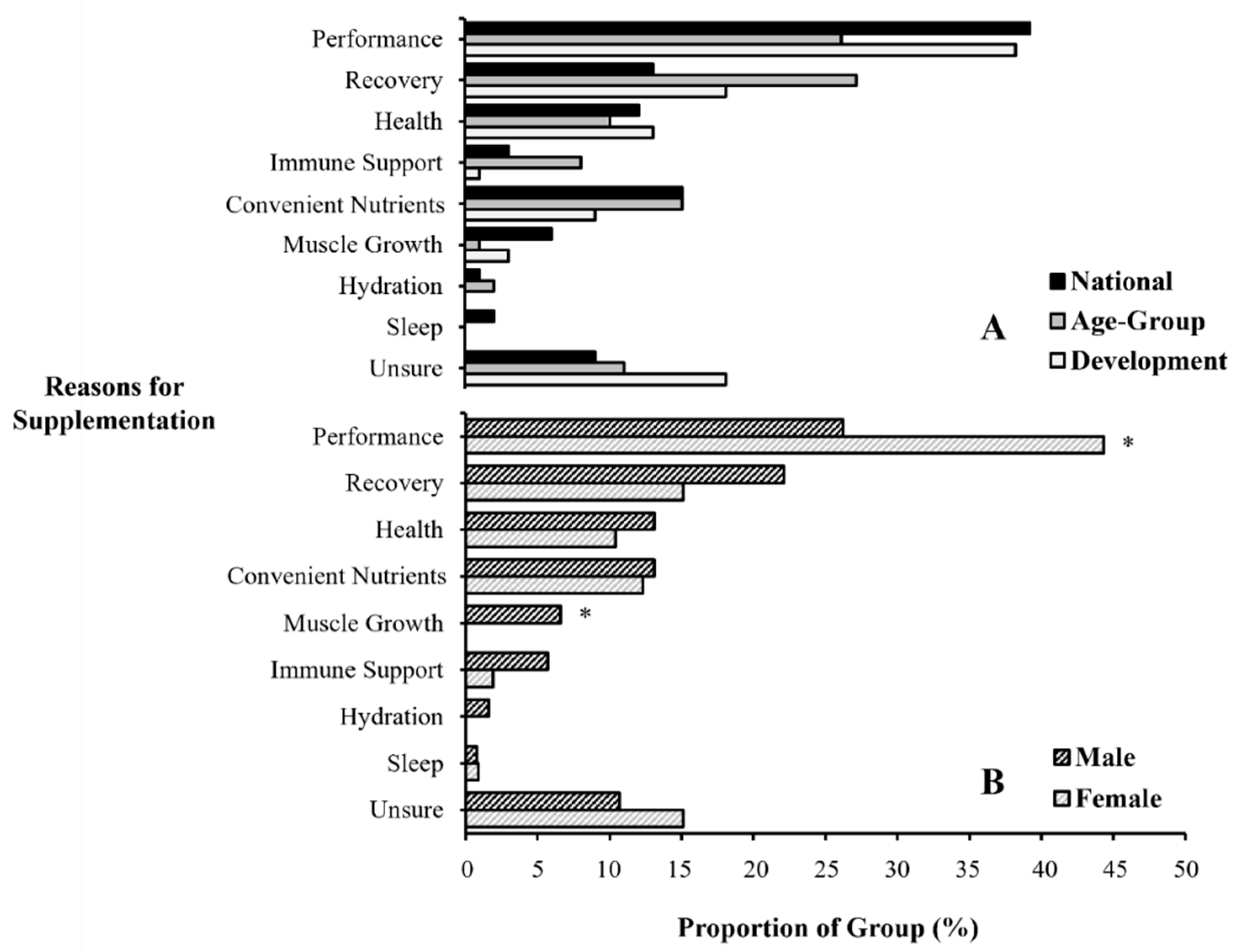

3.3. Reasons for Supplement Use

3.4. Information Sources

3.5. Supplement Frequency

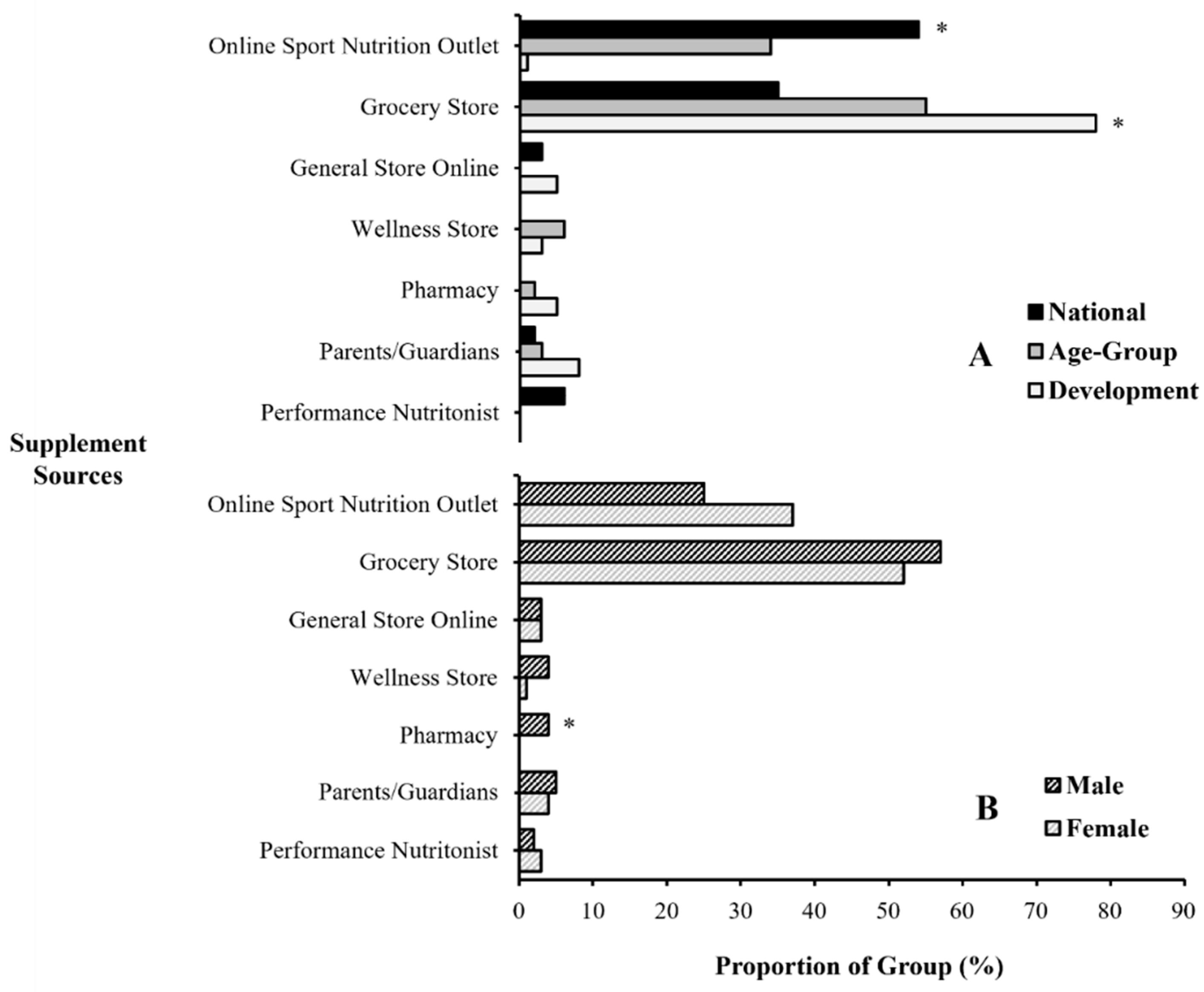

3.6. Supplement Sources

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maughan, R.J.; Burke, L.M.; Dvorak, J.; Larson-Meyer, D.E.; Peeling, P.; Phillips, S.M.; et al. IOC consensus statement: dietary supplements and the high-performance athlete. Br J Sports Med 2018, 52, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garthe, I.; Maughan, R.J. Athletes and supplements: prevalence and perspectives. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2018, 28, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winterstein, A.P.; Storrs, C.M. ; Herbal supplements: considerations for the athletic trainer. J Athl Train 2001, 36, 425–432. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, G.; Slater, G; Burke, L. M. Supplement use of elite Australian swimmers. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2016, 26, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettler, S; Lehner, G; Morgan, G. Widespread supplement intake and use of poor quality information in elite adolescent Swiss athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2022, 32, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulery, J.A.; Melton, B.F.; Bland, H.; Riggs, A.J. Associations between health status, training level, motivations for exercise, and supplement use among recreational runners. J Diet Suppl 2022, 19, 640–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, B; Kazlauskas, R. Medication use in athletes selected for doping control at the Sydney Olympics (2000). Clin J Sport Med 2003, 13, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Johnson, K; Pipe, A. L. The use of dietary supplements and medications by Canadian athletes at the Atlanta and Sydney Olympic Games. Clin J Sport Med 2006, 16, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylis, A.; Cameron-Smith, D.; Burke, L.M. Inadvertent doping through supplement use by athletes: assessment and management of the risk in Australia. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2001, 11, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.; Slater, G.; Burke, L.M. Changes in the supplementation practices of elite Australian swimmers over 11 years. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2016, 26, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanov, P.; Đorđić, V.; Obradović, B.; Barak, O.; Pezo, L.; Marić, A.; et al. Prevalence, knowledge and attitudes towards using sports supplements among young athletes. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2019, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, B.; Veiga, S.; Sánchez-Oliver, A.J.; Domínguez, R.; Morencos, E. Analysis of sport supplement consumption by competitive swimmers according to sex and competitive level. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dascombe, B.J.; Karunaratna, M.; Cartoon, J.; Fergie, B.; Goodman, C. Nutritional supplementation habits and perceptions of elite athletes within a state-based sporting institute. J Sci Med Sport 2010, 13, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berning, J.R.; Troup, J.P.; VanHandel, P.J.; Daniels, J.; Daniels, N. The nutritional habits of young adolescent swimmers. Int J Sport Nutr 1991, 1, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, A.C.; Ward, K.D.; Mirza, B.; Slawson, D.L.; McClanahan, B.S.; Vukadinovich, C. Comparison of nutritional intake in US adolescent swimmers and non-athletes. Health 2012, 4, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.; Pasquarelli, B.N.; Romaguera, D.; Arasa, C.; Tauler, P.; Aguiló, A. Anthropometric characteristics and nutritional profile of young amateur swimmers. J Strength Cond Res 2011, 25, 1126–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, J.A.; Wiens, K.P.; Erdman, K.A. Dietary intakes and supplement use in pre-adolescent and adolescent Canadian athletes. Nutrients 2016, 8, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petróczi, A.; Naughton, D.P.; Pearce, G.; Bailey, R.; Bloodworth, A.; McNamee, M. Nutritional supplement use by elite young UK athletes: fallacies of advice regarding efficacy. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2008, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, G.L.; Kasper, A.M.; Walsh, N.P.; Maughan, R.J. "Food first but not always food only": recommendations for using dietary supplements in sport. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2022, 32, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derave, W.; Tipton, K.D. Dietary supplements for aquatic sports. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2014, 24, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbrow, B.; McCormack, J.; Burke, L.M.; Cox, G.R.; Fallon, K.; Hislop, M.; et al. Sports Dietitians Australia position statement: sports nutrition for the adolescent athlete. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2014, 24, 570–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Oliver, A.J. Suplementación nutricional en la actividad físico-deportiva: análisis de la calidad del suplemento proteico consumido. Universidad de Granada 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Alfageme, R.; Domínguez, R.; Sanchez-Oliver, A.J.; Tapia-Castillo, P.; Martínez-Sanz, J.M.; Sospedra, I. Analysis of the consumption of sports supplements in open water swimmers according to the competitive level. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foo, W.L.; Faghy, M.A.; Sparks, A.; Newbury, J.W.; Gough, L.A. The effects of a nutrition education intervention on sports nutrition knowledge during a competitive season in highly trained adolescent swimmers. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Akoglu, H. User's guide to correlation coefficients. Turk J Emerg Med 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simič, V.; Mohorko, N. Nutritional strategies of Slovenian national junior swimming team. Ann Kinesiol 2018, 9, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.; Boyd, K.T.; Burke, L.M.; Koivisto, A. Nutrition for swimming. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2014, 24, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, H.; Koehler, K.; Geyer, H.; Kleiner, J.; Mester, J.; Schanzer, W. Dietary supplement use among elite young German athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2009, 19, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, K.; Erdman, K.A.; Stadnyk, M.; Parnell, J.A. Dietary supplement usage, motivation, and education in young, Canadian athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2014, 24, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | National (n = 11) |

Age-group (n = 13) |

Development (n = 20) |

Males (n = 21) |

Females (n = 23) |

Combined (n = 44) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20 ± 2 | 15 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 | 16 ± 3 | 15 ± 3 | 15 ± 3 |

| Years competitive | 9 ± 2*# | 5 ± 1* | 3 ± 1 | 5 ± 3 | 5 ± 3 | 5 ± 3 |

| Weekly training sessions | 6.9 ± 1.2* | 6.2 ± 0.8* | 5.7 ± 0.5 | 6.0 ± 0.7 | 6.3 ± 1.1 | 6.2 ± 0.9 |

| Weekly training hours | 17.6 ± 3.2* | 15.8 ± 2.4* | 12.3 ± 1.2 | 14.4 ± 2.3 | 14.9 ± 3.8 | 14.6 ± 3.1 |

| WA points | 698 ± 59*# | 622 ± 67* | 483 ± 69 | 555 ± 123 | 598 ± 99 | 578 ± 112 |

| Category / Individual Supplements | Overall (n = 44) |

National (n = 11) |

Age-group (n = 13) |

Development (n = 20) |

Males (n = 21) |

Females (n = 23) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (supplements) | 5.2 ± 2.9 | 8.1 ± 3.4 ab | 4.8 ± 2.0 | 3.9 ± 1.7 | 5.9 ± 2.7 | 4.6 ± 2.9 |

| Sports (supplements) | 2.5 ± 1.0*# | 2.7 ± 1.7 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 0.8† | 2.2 ± 1.0 |

| Dextrose/maltodextrin (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| Electrolytes (%) | 18 | 18 | 38 | 5 | 29 | 9 |

| Liquid meals (%) | 9 | 18 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 17‡ |

| Protein bars (%) | 43 | 36 | 54 | 40 | 57 | 30 |

| Protein-enhanced food (%) | 45 | 45 | 46 | 45 | 62‡ | 30 |

| Protein powder (%)† | 45 | 82 | 54 | 20 | 52 | 39 |

| Sports bars (%) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| Sports drinks (%)† | 68 | 27 | 62 | 95 | 67 | 70 |

| Sports gels (%) | 18 | 9 | 8 | 30 | 19 | 17 |

| Ergogenic (supplements) | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 2.4 ± 1.4 ab | 0.5 ± 0.5b | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 1.7 | 0.9 ± 1.2 |

| Beetroot juice (%) | 5 | 9 | 8 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Beta-alanine (%)† | 14 | 45 | 8 | 0 | 14 | 13 |

| Caffeine anhydrous (%)† | 30 | 82 | 23 | 5 | 14 | 43‡ |

| Caffeine drinks/gels (%)† | 9 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 9 |

| Citrulline malate (%) | 2 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Creatine monohydrate (%)† | 16 | 55 | 8 | 0 | 19 | 13 |

| Sodium bicarbonate (%)† | 9 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 9 |

| Health (supplements) | 1.8 ± 1.6* | 3.0 ± 1.3ab | 1.7 ± 1.8 | 1.3 ± 1.3 | 2.2 ± 1.4 | 1.5 ± 1.7 |

| Ginger (%) | 2 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Iron (%) | 20 | 27 | 15 | 20 | 24 | 17 |

| Magnesium (%)† | 5 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Melatonin (%) | 2 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Multi-vitamin (%) | 41 | 36 | 31 | 50 | 62‡ | 22 |

| Omega-3 fatty acids (%)† | 20 | 55 | 0 | 15 | 19 | 22 |

| Probiotics (%) | 20 | 9 | 38 | 15 | 24 | 17 |

| Vitamin C (%) | 18 | 27 | 31 | 5 | 24 | 13 |

| Vitamin D3 (%)† | 39 | 73 | 38 | 20 | 38 | 39 |

| Zinc (%)† | 11 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 13 |

| Information source | Overall (n = 228) |

National (n = 89) |

Age-group (n = 62) |

Development (n = 77) |

Males (n = 122) |

Females (n = 106) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance nutritionist (%)* | 33 | 51 | 50 | 0 | 20 | 48# |

| Swim coach (%)* | 6 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 5 |

| Parent/guardian (%)* | 42 | 16 | 40 | 74 | 50# | 33 |

| NGB (%) | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Medical doctor (%) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Other coach (%) | 4 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 6# | 1 |

| Teammate (%) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Friends and siblings (%) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Media (%)* | 3 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| Self-Research (%) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).