1. Introduction

Zucchini (

Cucurbita pepo L.), a highly polymorphic vegetable crop [

1], is an economically important crop in the Cucurbitaceae plant family and growing worldwide [

2]. Seed-producing zucchini (three to four hundred seeds per fruit) is widely cropped in China and the production area is about 87,000 ha [

3] and more than 200,000 ha (unpublished data) in Inner Mongolia and in China, respectively (

Figure 1a,b), since the health benefits and economic value of zucchini seeds have received increasing attention. Recent studies of fungal diseases in Cucurbitaceae include fruit rot of melon caused by

F. asiaticum [

4], the difference in the host range between

F. oxysoporum f. sp.

radicis-

cucumerinum (Forc) and

F.

oxysporum f. sp.

melonis (Fom) [

5], the five species of Fusarium causing fruit rot in melons in Brazil [

6].

F.

solani f. sp.

cucurbitae has a host specificity for cucurbits and caused an outbreak of Fusarium foot and fruit rot of pumpkin within the United States [

7]. The pathogen has also been reported as a new fungal disease affecting cucurbits production in Almerίa province of Spain [

8] and in Arkansas [

9]. However, there are few researches about the occurrence of the disease caused by Fusarium spp. in zucchini in China. Here we reported a fruit rot observed in seed-producing zucchini in Inner Mongolia, China and the pathogen was identified as

F.

solani f. sp.

cucurbitae.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples Collection

In August 2021, symptoms of fruit rot like in seed-producing zucchini where the fruit was in contact with the soil were observed on commercial cultivar Jindi 1 in fields in Wuyuan region in Inner Mongolia, including dry, dark grey, spongy lesions (4 to 5 cm diameter) with a light brown halo (

Figure 1c–f). The incidence of infected fruits was ranged from 10 to 30%. Six infected fruits were collected from three fields for pathogens isolation and identification.

2.2. Isolation and Purification of the pathogens

Lesions were cut out from infected fruit samples and the materials were then surface disinfected by 2% NaClO and 75% ethanol for 30 s, respectively, followed by two minute rinses in sterile water. Fruit materials were then dried on sterile filter paper before being placed on potato dextrose agar (PDA) and incubated at 25℃ in the dark. 5 days later, grey white mycelium was observed then purified cultures were obtained using the single spore method.

2.3. Morphological and Molecular Identification

Morphological characteristics were observed by culturing the two representative isolates (Fx-1a、Fx-1b) on PDA at 25℃ in the dark for 5 days. Microscopy of spore morphology of the isolates were performed by using a Nikon ECLIPSE NI-U compound microscope fitted with a Nikon Y-TV55 digital camera. For the total DNA extraction, isolates were cultured in Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB) at 25℃ on a shaker at 150 rpm for 5 days. Genomic DNA was extracted using the

EasyPure@ Genomic DNA Kit (TransGen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR amplifications of the isolates were performed for part of the translation (

TEF1-α) using the primers EF1 and EF2 and the second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (

RPB2) using the primers 5f2 and 7cr under the PCR reaction conditions described previous [

8]. The amplicons were Sanger sequenced at BGI Tech Solutions (Beijing Liuhe) CO., LIMITED, China.

TEF1-α and

RPB2 gene sequences selected from NCBI and the Fusarium database [

10] were analyzed and combined in Geneious and aligned by Clustal W and analyzed using maximum likelihood with bootstrap method (=1000) in MEGA 11.0.

2.4. Pathogenicity Assay

To evaluate the pathogenicity of the isolate on zucchini fruits, two tests were conducted independently. Fruits were washed under running water, disinfected with 75% ethanol for 3 times and six wounds (approximately 1-2 mm deep) were made with a sterile 5-mm-diameter cork borer in the fruit surface. Four mycelial plugs (5 mm) cut from the margin of 8-day-old culture on PDA plate were placed mycelium side down into the wounds and two plain PDA plugs were inoculated as controls [

8,

11]. For testing if the isolate is pathogenic to the zucchini plant [

8], zucchini seedling at the first true leaf stage grown in a pot (10.5 cm×8.8 cm) was inoculated with a soil drench [

12]. A 10-days-old colonized PDA petri plate (9 cm) of the isolate was scraped and diluted in 30 ml distilled water. Inoculum (10

6 CFU/mL) at 4 ml per plant was injected in the soil around the stem without wounding the plants. Six replicates were inoculated (one plant per pot) as a treated group and four uninoculated seedlings served as controls. Fruits and plants were kept at 22 to 24°C in a moisty chamber (16 h light/8 h dark, approximately 70%).

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Identification

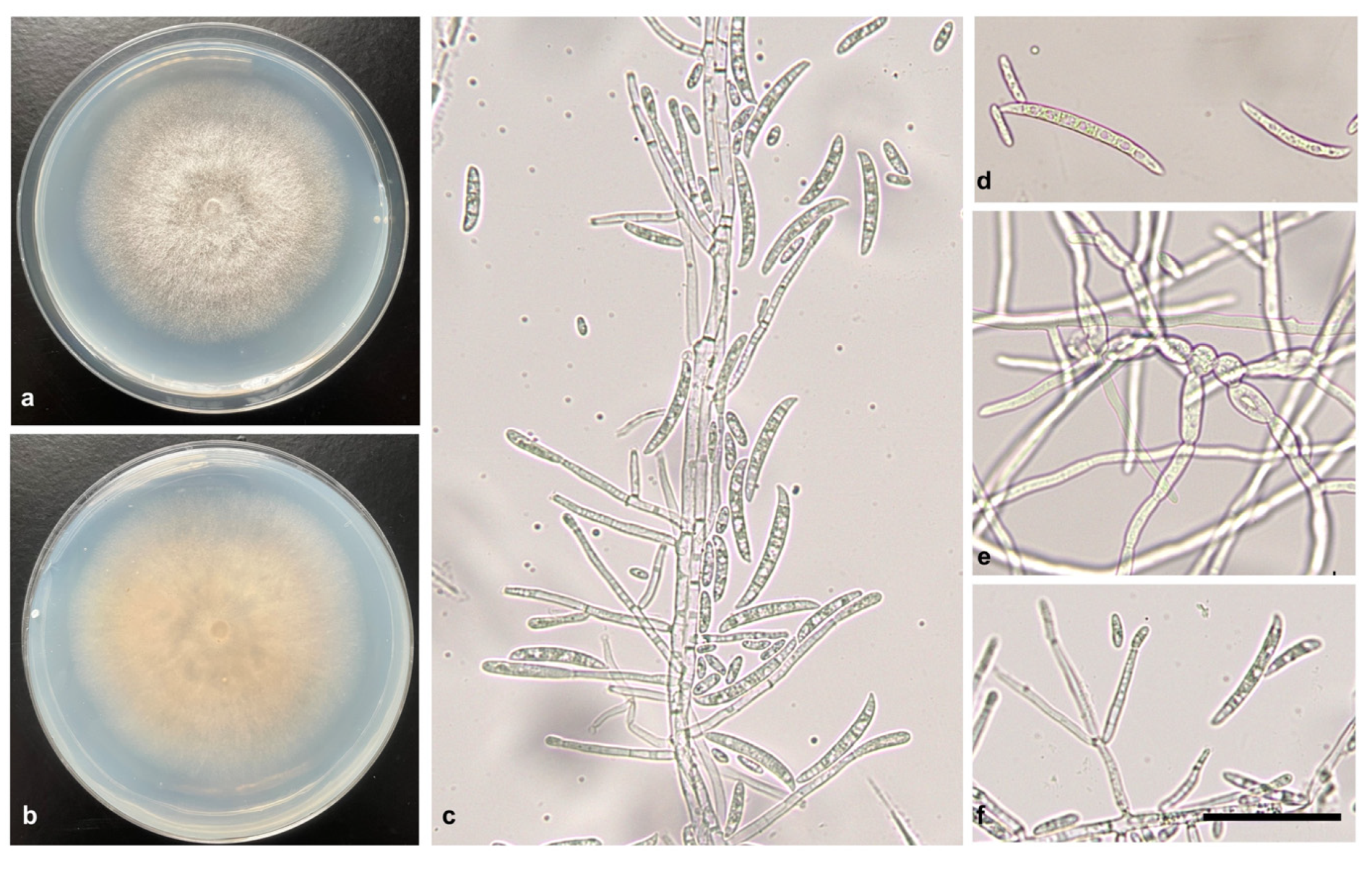

Colony surface of isolations consisted in white and cottony with white to straw aerial mycelium (

Figure 2a,b) and sporulation was abundant with microconidia (7.1 × 2.4 to 19.1 × 3.6 μm) and macroconidia (40.5 × 4.8 to 67.0 × 6.0 μm) formed from conidiophores (

Figure 2c,d,f). Intercalary chlamydospores were produced on conidial hyphae (

Figure 2e). Ten Isolates from symptomatic fruits were consistently identified as Fusarium species based on the morphological characters [

13] in potato dextrose agar (PDA).

3.2. Molecular Identification

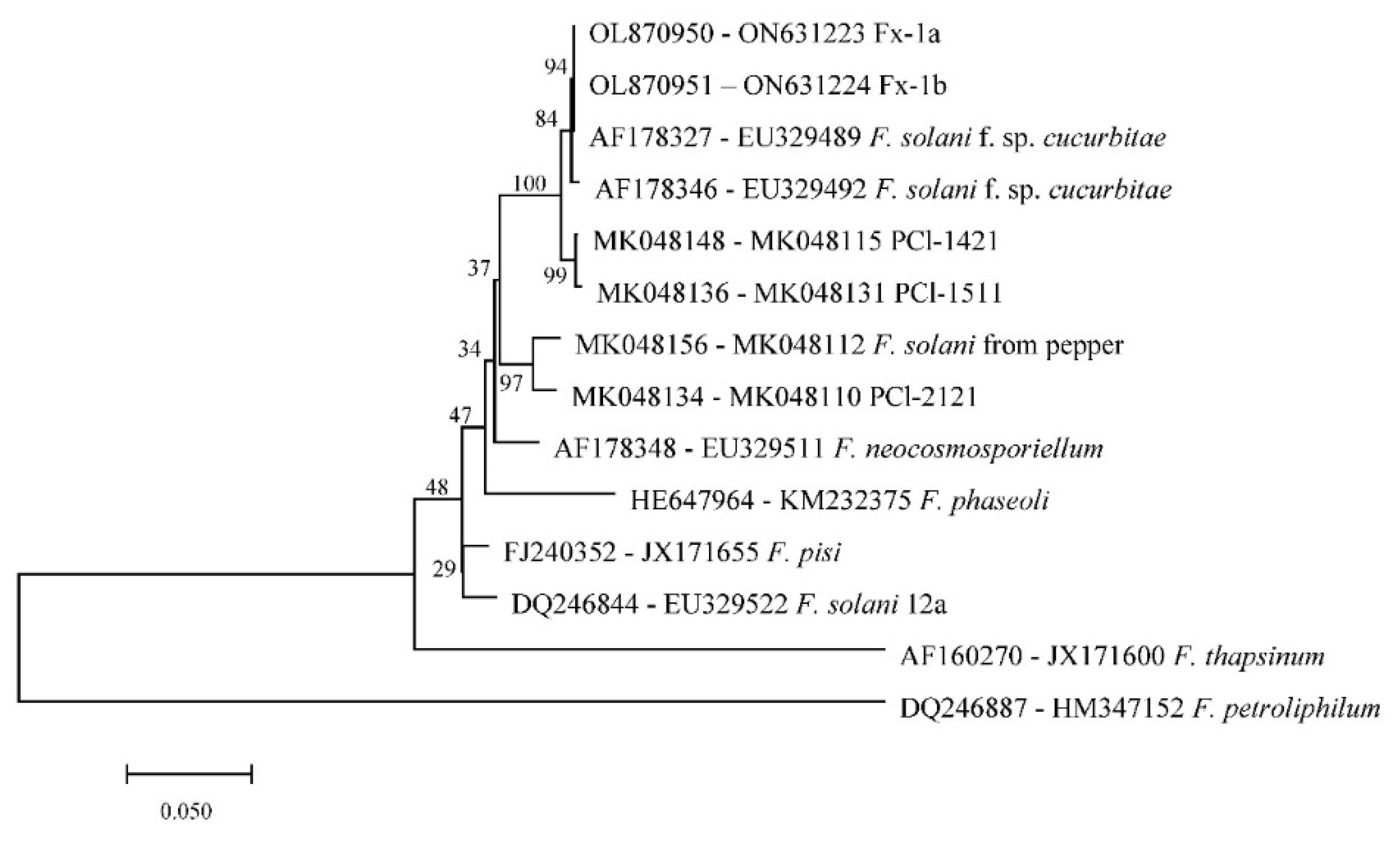

The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, the translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene (TEF-1α) and the RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (RPB2) were amplified and sequenced, and had 100% identity homology with those of F. solani, e.g., MT032588 (ITS), KF372878 (TEF-1α) and OK595060 (RPB2) in the NCBI GenBank database, respectively. Phylogenetic tree (

Figure 3) was constructed by concatenating TEF-1α and RPB2 gene and exhibited the two isolates in this study clustered together with the F. solani f. sp. cucurbitae sequences (AF178327 and EU329489). Accession numbers of the genes sequenced in this study were provided in supplementary materials.

3.3. Pathogenicity Determination

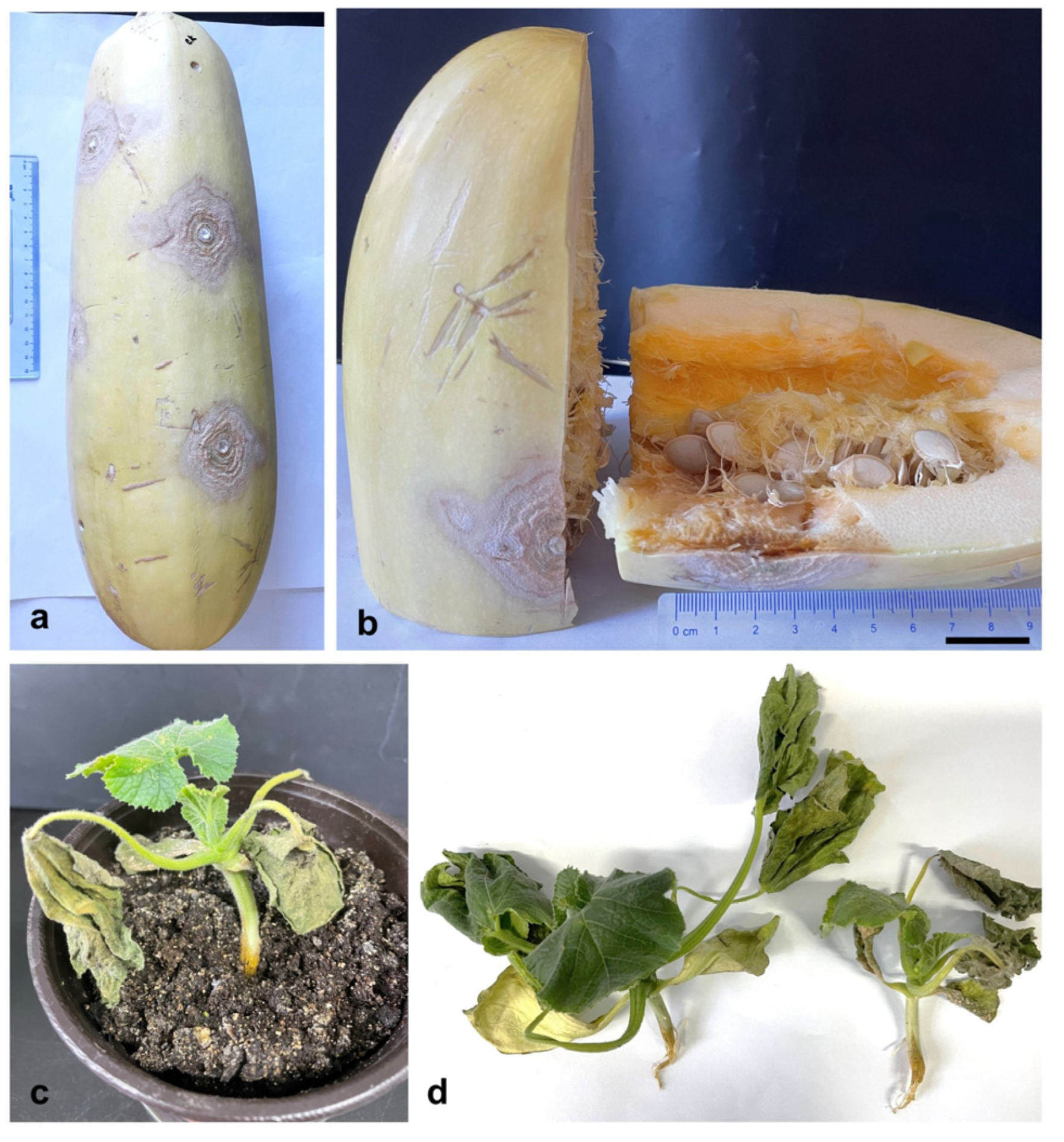

After 9 days post inoculation, lesions over 3 cm in diameter were produced on the fruits (

Figure 4a,b), which were similar to those in naturally infected fruits. All plants inoculated exhibited brown, water-soaked rot at the base of the stem with chlorosis and wilting at 12 dpi (

Figure 4c,d), whereas the negative-controls remained asymptomatic. The colonies reisolated from the inoculated fruits and plants were morphologically identical to the original isolate, thus fulfilling Koch’s postulates.

4. Discussion

Fusarium species are soilborne fungal pathogens that cause severe economic damage in different agricultural production [

14]. Nevertheless, Fusarium can survive in seed but does not affect the germination or viability of the seed [

15].

F. solani f. sp.

cucurbitae was firstly demonstrated spreading by seed transmission in 1961 [

16] and a further study provided that seed infestation and infection occurs once the lesion on the fruit rind extends to the margin of the seed cavity [

15]. In the present study, the lesions on the infected zucchini fruit were developing inside the fruit both in fields and in pathogenicity assays, implying the disease might affect the seed cavity or cause the seeds infection, which will be addressed in future studies. Therefore, pathogen-free seed is recommended for seed producers and zucchini growers to reduce potential pathogens.

The diseases caused by viral pathogen and

Phytophthora capsici Leonian of zucchini in China get increasing concerns due to the visible symptoms and yield loss [

3,

17,

18]. However, the fruit rot reported in this study commonly occur on where the fruit in contact with the soil, which is easily ignored by farmers at the beginning. Based on the results of the present study, it was provided more information on the diagnosis and identification of the fruit rot of seed producing zucchini. Moreover, this study demonstrated that the isolate of

F. solani f. sp.

cucurbitae was also pathogenic to the zucchini seedlings as previously reported for this pathogen, a causal agent of Fusarium crown and root rot [

19], but disease symptoms of root were not obvious in the fields where the fruit rot were found in Wuyuan regions, Inner Mongolia (data not shown). It was indicated that the pathogen could be a potential threaten to zucchini plants once the weather conditions are appropriate.

In summary, this is the first report of fruit rot of zucchini caused by F. solani f. sp. cucurbitae in Inner Mongolia, China.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Z. and Y.Y.; methodology, Y.Y. and H.S.; software, Y.Y and C. J.; validation, Zq. L. and Zn. L.; formal analysis, Zq.L. and Zq. L.; investigation, Q.Z.; resources, Q.Z. and C. J.; data curation, Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y. and H.S.; writing—review and editing, Zn.L and Zq. L.; visualization, Y.Y and C. J.; supervision, Zn.L., Q.Z. and Zi. L.; project administration, Y.Y. and C.J.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Inner Mongolia Agricultural and Animal Husbandry Youth Innovation Fund Project (2022QNJJN10) and Inner Mongolia Research Foundation for Introducing Talented Scholars.

Data Availability Statement

The sequence data of TEF1-α and ITS genes in the isolates have been submitted to GenBank databases under accession numbers OL870950, OL870951, OL871487 and OL871488, which are accessible on 31 January 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abd-Elkader, D.Y. , Mohamed, A. A., Feleafel, M.N., Al-Huqail, A.A., Salem, M.Z.M., Ali, H.M., and Hassan, H.S., Photosynthetic pigments and biochemical response of zucchini (Cucurbita pepo L.) to plant-derived extracts, microbial, and potassium silicate as biostimulants under greenhouse conditions. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 879545. [Google Scholar]

- Djitro, N. , Roach, R. , Mann, R., Rodoni, B., and Gambley, C., Characterization of Pseudomonas syringae Isolated from Systemic Infection of Zucchini in Australia. Plant Disease 2022, 106, 541–548. [Google Scholar]

- Jianying, Y. , Xuefeng, W. , Hongli, Z., Zhengnan, L., and Mingmin, Z., Identidication of viral pathogen of zucchini in Inner Mongolia. Journal of Northwest A&F University (Nat. Sci. Ed) 2021, 49, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, F. , Zang, Q. , Ding, W., Ma, E., Huang, Y., and Wang, Y., First report of fruit rot of melon caused by Fusarium asiaticum in China. Plant Disease 2021, 105, 1225. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. , Fokkens, L. , and Rep, M., A single gene in Fusarium oxysporum limits host range. Mol Plant Pathol 2021, 22, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida Nogueira, G. , Costa Conrado, V. S., Luiz de Almeida Freires, A., Ferreira de Souza, J.J., Figueiredo, F.R.A., Barroso, K.A., Medeiros Araújo, M.B., Nascimento, L.V., de Lima, J.S.S., Neto, F.B., da Silva, W.L., and Ambrósio, M.M.d.Q., Aggressivity of different Fusarium Species causing fruit rot in melons in Brazil. Plant Disease 2023, 107, 886–892. [Google Scholar]

- Elmer, W.H. , Covert, S.F., and O’Donnell, K., Investigation of an outbreak of Fusarium foot and fruit rot of pumpkin within the United States. Plant Disease 91, 1142-1146.

- Pérez-Hernández, A. , Rocha, L.O., Porcel-Rodríguez, E., Summerell, B.A., Liew, E.C.Y., and Gómez-Vázquez, J.M., Pathogenic, morphological, and phylogenetic characterization of Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae isolates from cucurbits in Almería Province, Spain. Plant Disease 2020, 104, 1465–1476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Castroagudin, V.L. , Correll, J.C., and Cartwright, R.D., First report of fruit rot of pumpkin caused by Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae in Arkansas. Plant Disease 2009, 93, 669–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Cruz, T.J. , Whitaker, B. K., Proctor, R.H., Broders, K., Laraba, I., Kim, H.-S., Brown, D.W., O’Donnell, K., Estrada-Rodríguez, T.L., Lee, Y.-H., Cheong, K., Wallace, E.C., McGee, C.T., Kang, S., and Geiser, D.M., FUSARIUM-ID v.3.0: An updated,downloadable resource for Fusarium species identification. Plant Disease 2022, 106, 1610–1616. [Google Scholar]

- Vitale, S. , Maccaroni, M., and Belisario, A., First report of zucchini collapse by Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae race 1 and Plectosporium tabacinum in Italy. Plant Disease 2007, 91, 325–325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gómez, J. , Guerra-Sanz, J.M., Sánchez-Guerrero, M.C., Serrano, Y., and Melero-Vara, J.M., Crown rot of zucchini squash caused by Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae in Almería Province, Spain. Plant Disease 2008, 92, 1137–1137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Hernández, A. , Etiology, epidemiology and control of Fusarium crown and foot rot of zucchini caused by Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae. 2020.

- Leonce, D. , Fusarium soilborne pathogen, in Fusarium, M. Seyed Mahyar, Editor. 2021, IntechOpen: Rijeka. p. Ch. 3.

- Mehl, H.L. and Epstein, L., Identification of Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae race 1 and race 2 with PCR and production of disease-free pumpkin seeds. Plant Disease 2007, 91, 1288–1292. [Google Scholar]

- Toussoun, T.A. and Snyder, W.C., The pathogenicity, distribution, and control of two races of Fusarium (Hypomyces) solani f. cucurbitae. Phytopathology 1961, 51, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S. , Ping, W., Ke, X., and Zhaoxin, W., Virus identificaion and evaluation of disinfection effect of seed-used pumpkin (Cucurbita peop L.) in Inner Mongolia. Journal of Northwest A&F Universith (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 51, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jie, L. , Xun, W. , Dao-long, D., Jie, L., Xi, Z., Xiao-juan, L., Xiao-dan, W., and Zhu-gang, L., The occurrence of Phytophthora blight,pathogenicity identification of isolates, germplasm resistance evaluation of seed-used pumpkin in Heilongjiang province. ACTA PHYTOPATHOLOGICA SINICA 2021, 51, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Hernandez, A. , Porcel-Rodriguez, E., and Gomez-Vazquez, J., Survival of Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae and fungicide application, soil solarization, and biosolarization for control of crown and foot rot of zucchini squash. Plant Dis 2017, 101, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).