1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancer is a group of cancers that can affect any part of the GI tract, such as esophageal, gastric, colorectal, anal, gall bladder, pancreatic, and liver [

1]. GI cancer is among the leading cause of death in the United States (U.S.) [

2]. GI cancer in the U.S. is projected to account for 34% of cancer incidence [

1]. The 5-year overall age-standardized relative GI cancer survival rate is rising due to improvements in early identification and treatment (42% between 1975 and 1990 to 94% between 2012 and 2018) in the U.S. in all combined cancer stages and GI cancer types [

2]. It is predicted that by 2050, there will be 350,000 GI cancer survivors living in the U.S. [

1,

2,

3].

As more GI cancer survivors live longer, health-related quality of life (HRQoL)[

3] becomes increasingly significant among this group. Many GI cancer survivors experience poor HRQoL [4-6]. Indeed, a growing number of GI cancer survivors, not only are living longer, but also are burdened with the risk of cancer recurrence, financial distress, the long-term symptom consequences of cancer per se, and its treatment [6-8]. The multiple burdens (e.g., physical challenges) in GI cancer survivors can significantly impact their HRQoL [2, 4-7, 9].

Of note, significant cancer survivorship disparities were observed across various social and behavioral determinants of health (SBDH) factors such as race, income status, or education levels, and health risk behaviors [10, 11]. Therefore, understanding the associations of SBDH factors with HRQoL of GI cancer survivors can inform targeted interventions to improve their overall well-being. However, identifying GI cancer survivors at a high risk of developing poor HRQoL is under-investigated [

12].

To our knowledge, while numerous studies have shown that SBDH have a significant impact on cancer survival and mortality rates [11, 13, 14], very few studies have examined SBDH risk factors of HRQoL in cancer survivors in the U.S. [

15]. For example, higher income was associated with better HRQoL, whereas lower educational status negatively impacted HRQoL among Hispanic/Latino-American cancer survivors in mixed cancer types [

16] or in breast cancer survivors [17, 18]. Burse et al. (2022) [

15] also examined the association between SBDH and HRQoL in cancer survivors with mixed cancer types in the U.S. Burse et al. found that current smoking was positively and significantly associated with poor physical HRQoL, but healthy eating (e.g., fruit and vegetable consumption), heavy alcohol consumption, and health care coverage were not associated with HRQoL after covariate adjustment. However, these studies [15-18] were limited in identifying the most significant SBDH risk factors of poor HRQoL, specific to GI cancer survivors.

Understanding the roles of SBDH on HRQoL among GI cancer survivors is crucial to gain insight into the specific social challenges and needs of this population. Lower socioeconomic status and poor lifestyle, including health risk behaviors, are associated with a higher risk of GI cancer, as well as higher mortality and recurrence rates in GI cancers [

17]. Poor diet (e.g., red meat, fast food consumption), sedentary lifestyles, and smoking status contribute to GI cancer development as well as poor disease prognosis [

19]. SBDH may play a role in not only the risk for GI cancer development but also hastening symptoms and poor HRQOL. Researchers have identified that poor SBDH were associated with severe and frequent GI and psychological symptoms [4-7], which contribute to the risk of poor physical and mental HRQoL in GI cancer survivors.

Marco et al. (2019)[

20] reported that cancer survivors with prostate, melanoma, gynecological, and urological cancers had higher HRQoL scores than those with colorectal cancer. Thus, HRQoL can differ by cancer type, thus, it is important to identify SBDH risk factors of HRQoL specific to GI cancer survivors instead of examining these relations in all combined cancer types [

20].

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the associations of SBDH with HRQoL among GI cancer survivors in the U.S. Our aims are to: (1) identify the most influential or significant risk factors of poor HRQoL outcomes (general, physical, and mental) including demographic and clinical characteristics, and SBDH (e.g., race, health risk behaviors, income, education, health care access, homeownership); and (2) to quantify the associations of SBDH with HRQoL after covariate adjustment among GI cancer survivors. Our focused SBDH as primary risk factors of poor HRQoL. Significant demographic and clinical characteristics related to HRQoL in Aim 1 were adjusted as covariates in Aim 2.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

A nationwide telephone survey known as the Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS) was launched by the CDC in 1984 [

21]. In all 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and three U.S. territories, BRFSS interviewers gather information on health-related behaviors, sociodemographic factors, the top preventable causes of death, and preventive health practices among non-institutionalized residents (18 years of age or older). The BRFSS conducts surveys over landlines or cellular telephones using a random digit dialing sampling technique. The validity and reliability of BRFSS data have been demonstrated [

21]. We conducted a secondary data analysis using publicly available BRFSS survey data. The institutional review board (IRB) waived approval for this study.

A cross-sectional study was conducted by combining BRFSS data in GI cancer survivors from 2014 to 2021 except for 2015 (due to no GI cancer data availability).

Survey questions about diet were asked only in the survey for the years 2017, 2019, and 2021. We merged surveys to examine diet (the surveys 2017, 2019, and 2021) as a risk factor for HRQoL. Individuals > 18 years old who self-reported a personal history of esophageal, stomach, colon, rectal, liver, and pancreatic cancers were included as adult GI cancer survivors in this study. We excluded individuals if they refused to respond to any of the survey questions or had missing responses or values of any of the included variables used in this study.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Primary Outcomes of Interest

CDC’s HRQoL-4 measure was used in this study. The CDC HRQoL-4 measure included self-reported general, physical, and mental health status and usual activity limitations by physical or mental health status [

16]. Our primary outcomes include all three items of the HRQoL-4 measure - general, physical, and mental health items. The following survey questions were used to measure each health status [

21]: for general health, “

Would you say that in general, your health is excellent, very good, good, fair or poor”; for physical health, “

Now thinking about your physical health, which includes physical illness and injury, for how many days during the past 30 days was your physical health not good?”; and for mental health, “

Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?” We used the cutoff for categorizing the primary outcomes validated by CDC [

22]. General health was dichotomized as “better” if answered as excellent, very good, or good versus “poor” if answered as fair or poor. Physical and mental health status were also dichotomized as “better” versus “poor.” Better physical health was defined as having 0 to 13 physically unhealthy days, while poor physical health was defined as having 14 or more such days. Similarly, mental health was defined as having 0 to 13 mentally unhealthy days, while poor mental health was defined as having 14 or more such days.

2.2.2. Correlates of HRQoL: Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

In the BRFSS data, we included age, sex, GI cancer types, and comorbidities as demographic and clinical characteristics as potential covariates.

2.2.3. Social and Behavioral Determinants of Health (SBDH)

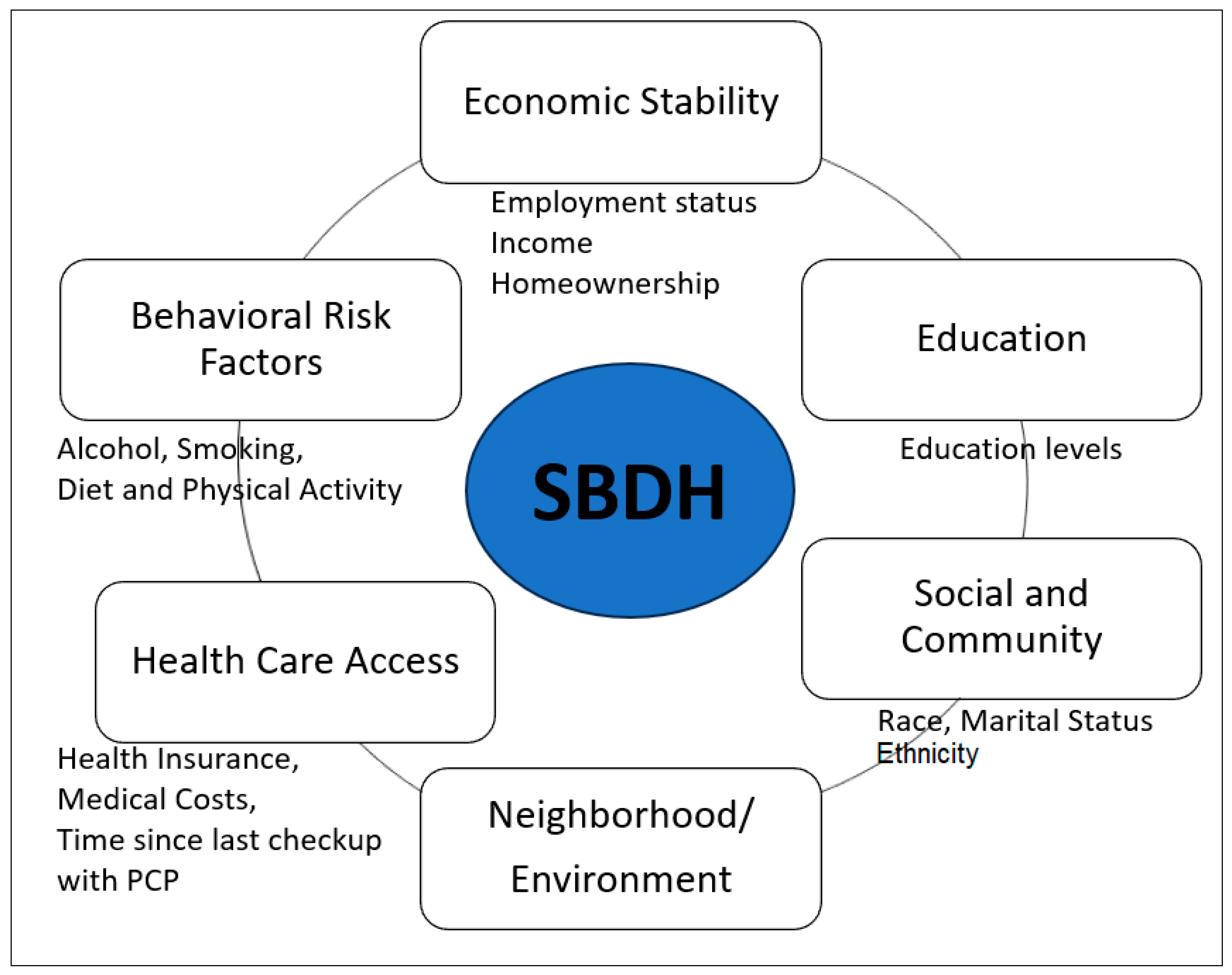

In our study, SBDH was measured as a risk factor for poor HRQoL, including social determinants of health (SDOH) and health risk behaviors. Healthy People 2030, a national health initiative [

23], sorts social determinants of health (SDOH) into five key areas of economic status, education, social and community context, healthcare access and quality, and neighborhood and built environment. To correspond BRFSS data to the SDOH in accordance with Healthy People 2030, we included social community context (race, ethnicity, and marital status), education, economic status (annual household income, employment status, homeownership – rent versus own home), and healthcare access (health care insurance coverage, time since the last health checkup, and concerns of medical costs limited the number of doctor visits). There were no available variables of BRFSS data that matched up with neighborhood and built environment area of the Healthy People 2030. In our study, we further included behavioral risk factors including diet, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and smoking status (

Figure 1). The diet variable (fruit and vegetable consumption per day) was grouped into two categories: “Less than one time per day” and “One or more times per day.” The BRFSS physical activity questions, “Adults who reported doing overall routine physical activity or exercise during the past 30 days other than their regular jobs? and no physical activity or exercise during the past 30 days,” were used for the current study. The BRFSS defined heavy drinking as having more than seven drinks per week for women and more than 14 drinks per week for men. Current smoking was considered a binary variable (either "yes" or "no") [

24]. None of the variables related to social and community context, quality of care, or environmental factors (e.g., zip code, pervert index, environmental safety, transportation) were available in the BRFSS dataset of GI cancer survivors.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The BRFSS is designed to obtain health-related information on the population of interest. i.e., the adult U.S. population residing in different states [

23]. Data weighting helps make sample data more representative of the population from which the data were collected. BRFSS data weights incorporate both population characteristics and BRFSS survey design. BRFSS weighting methodology consists of 1) design weight or factors, and 2) some method of adjusting the population’s demographics, such as ranking or interactive proportional fitting. The design weight accounts for the probability of selection and adjusts for nonresponse bias and non-coverage errors [

25]. Complex survey procedures with appropriate stratification and weighting of the data were applied to the study sample in our study.

The statistical analysis for this study involves a combination of descriptive statistics, univariate analysis, and logistic regression. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the main outcomes and participants’ characteristics. To examine the unadjusted correlated with HRQoL outcomes, the Chi-square test was used to analyze categorical independent variables, and the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used for continuous independent variables. Logistic regression was then used to estimate the odds ratios (O.R.s) and 95% confidence intervals (C.I.s) for the association between each HRQoL outcome and SBDH. We only included SBDH factors in the regression models if they were significantly associated with HRQoL outcomes. Correlation analyses between the independent variables and variance inflation factors (VIF) were calculated to assess multi-collinearity, if the VIF is greater than 5 for the current study [

26]. Stepwise eliminations were performed in multivariate regression models to select a parsimonious model while minimizing collinearity among variables [

27]. The survey years, demographic and clinical characteristics significantly associated with HRQoL were adjusted as covariates for the final regression model. Unadjusted and adjusted O.R.s and 95% C.I.s were reported for the final models. All statistical analyses are performed using R statistical software program. The level of significance for all analyses was set at p < 0.05 (two-sided).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

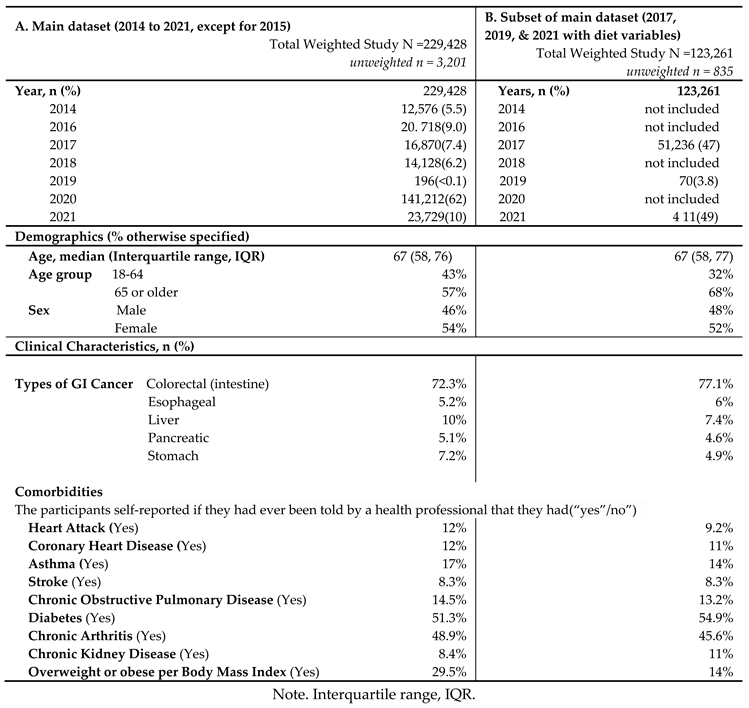

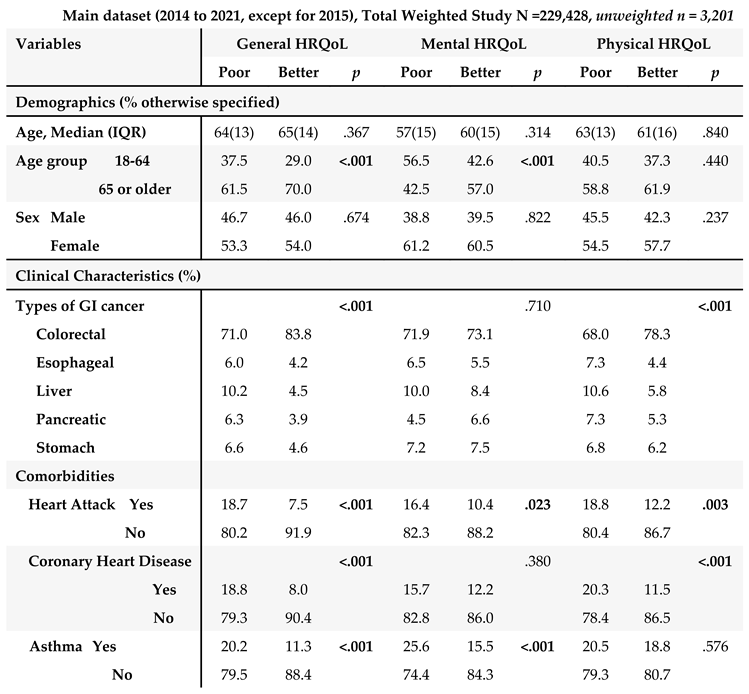

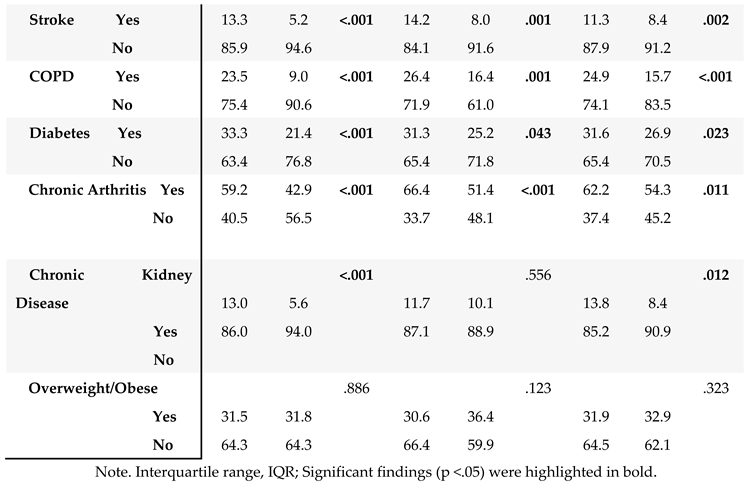

The unweighted population consisted of 3,201 GI cancer survivors (

Table 1). Weighting to the respective state populations, cancer survivors represented 229,428 adult GI cancer survivors in the combined dataset from 2014 to 2021 except for 2015 (

Table 1). The demographic and clinical characteristics are described in

Table 1.

In main dataset, about half of the GI cancer survivors were 65 years or older (57%) with a median age of 67 years old, and female (54%) (

Table 1A). Among GI cancer survivors, colorectal cancer was the most common cancer (72.3%), followed by liver cancer (10%), and stomach cancer (7.2%). In terms of comorbidities, diabetes (51.3%) was the most common chronic condition, followed by chronic arthritis (48.9%) among GI cancer survivors. In the subset of the main dataset combining 2017, 2019, and 2021 surveys with available diet variables (

Table 1B), similar results were found: Majority of GI cancer survivors were 65 years or older (68%), female (52%), and ever having been diagnosed with colorectal cancer (77.1%). Diabetes and chronic arthritis were the most common chronic conditions.

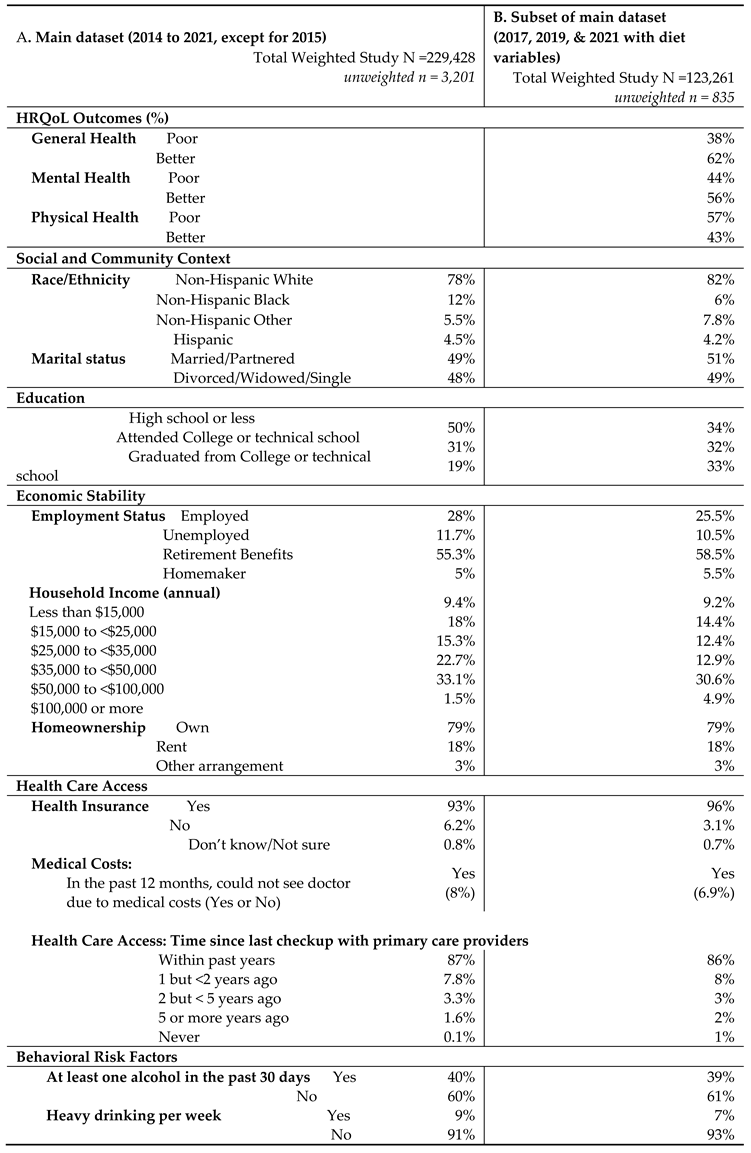

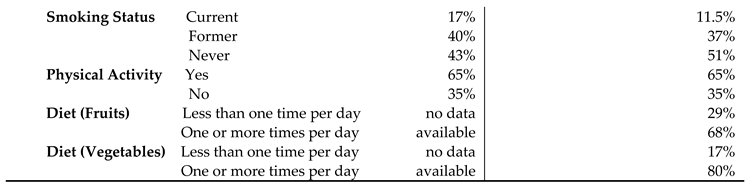

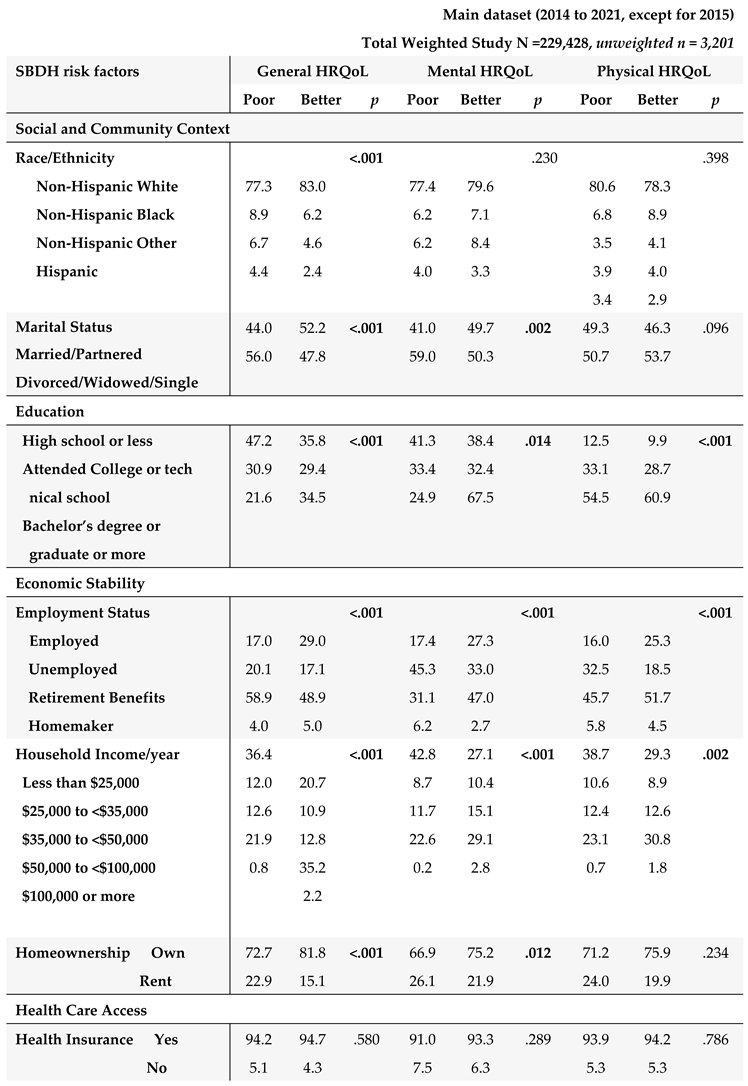

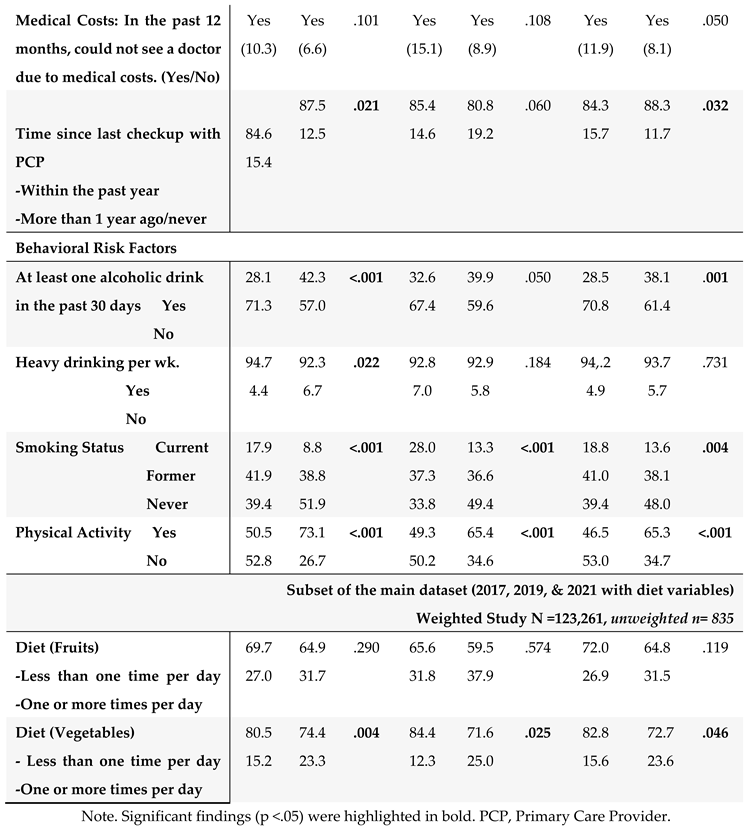

3.2. HRQoL Outcomes and SBDH

The HRQOL and SBDH factors are described in

Table 2. In the main BRFSS dataset, over half of GI cancer survivors reported better general (62%) and mental (56%) HRQoL, while 43% reported better physical HRQoL (

Table 2A). In main dataset, approximately half of GI cancer survivors were married or partnered (49%) and had at least a college education (50%). 78% of GI cancer survivors were non-Hispanic White. About 57.3% of the cancer survivors had an annual household income of at least

$35,000, and 93% had healthcare coverage. Most of the cancer survivors were on retirement benefits (55.3%), homeowners (79%), not heavy drinkers (91%), and not current smokers (83%). About 65% of GI cancer survivors reported routine physical activity or exercise over the last month. Similar results were found in the subset of BRFSS data combing 2017, 2019, and 2021. In this subset of BRFSS data (

Table 2B), the majority of participants have consumed fruits (68%) and vegetables (80%) one or more times per day.

3.3. Correlates of HRQoL: Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

We examined demographic and clinical characteristics with HRQoL to identify potential covariates for our primary analyses (i.e., SBDH and HRQoL) (

Table 3). Older age group, married/partnered, and no diagnosis of asthma were significantly associated with better general and mental HRQoL (

Ps <.001). Several chronic conditions were associated with poor HRQoL in all three HRQoL outcomes. Ever having been diagnosed with colorectal cancer (compared to other types of GI cancer such as liver and pancreatic cancers), no past medical history of coronary heart disease and chronic kidney disease were significantly associated with better general and physical HRQoL (

Ps <.05).

3.4. Potential Impact of SBDH on HRQoL

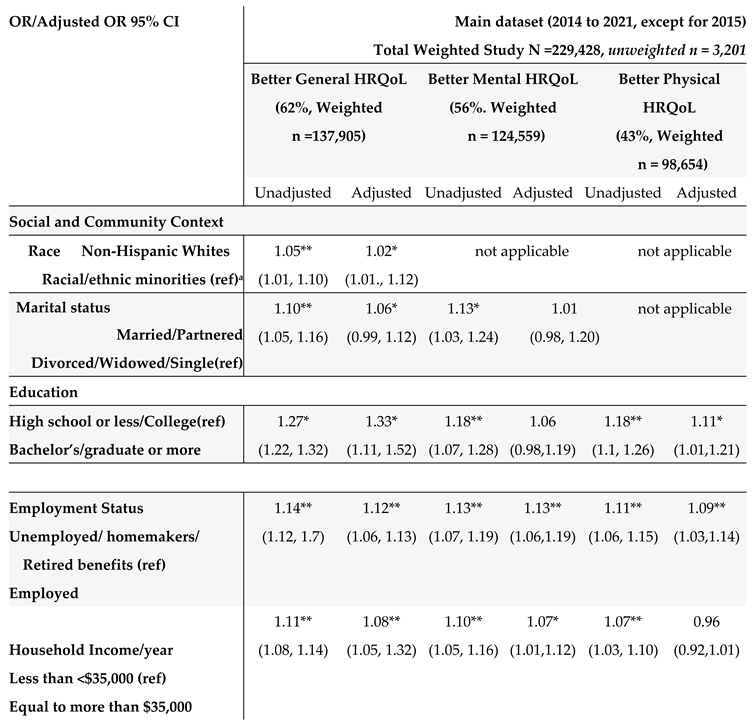

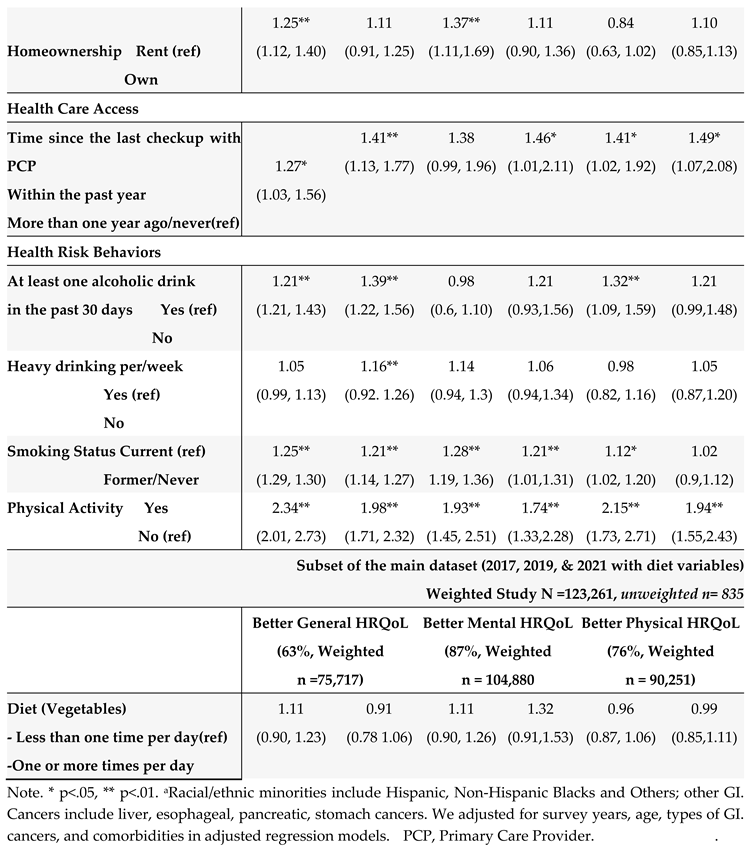

The associations of SBDH with HRQoL are described in

Table 4.

Given the significant correlates of SBDH with HRQoL (

Table 4), we further quantify the potential impact of SBDH on HRQoL using regression models. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (O.R.s) of each HRQoL outcome in relation to the SBDH are shown in

Table 5. In the unadjusted models, many SBDH factors significantly increased the risk of poor general, mental, and physical HRQoL (e.g., racial and ethnic minorities, non-married or partnered status, lower education and income levels, unemployment, home renters, more time since the last checkup, poor health behaviors- heavy alcohol drinking, current smoking, and lack of physical activity). However, daily fruit and vegetable consumption, health insurance, and medical costs were not significantly associated with HRQoL.

In the adjusted multivariate logistic models adjusting covariates (survey years, age, GI cancer types, and comorbidities) (

Table 5), among social determinants of health, non-Hispanic Whites (OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.10) and married/partnered status (OR = 1.10, 95% CI= 1.05 to 1.16), higher education levels (OR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.11, 1.52), being employed (OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.06, 1.13), higher income (OR = 1.08, 95% CI= 1.05, 1.32), and health care access within the past year since the last checkup with primary care provider (OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.13, 1.77), were associated with better general health HRQoL. Similar results were found for mental and physical HRQoL. Regarding behavioral determinants of health, lack of physical activity, alcohol consumption, and current smoking were significantly associated with poor HRQoL (all three outcomes). Among all SBDH in our study, physical activity participation was the most significant risk factor for better HRQoL (OR = 1.98 for general, OR =1.74 for mental, and OR = 1.94 for physical HRQOL), followed by better health care access (frequent health checkup) (OR = 1.41 for general, OR = 1.46, for mental, and OR = 1.49 for physical HRQOL).

4. Discussion

The current study marks the initial exploration of SBDH risk factors of HRQoL among U.S. adults with various GI cancer types, encompassing social and behavioral factors of SBDH. Our findings underscore the significant associations of poor HRQoL with many individual-level demographic and clinical characteristics, and SBDH in poor status, such as low economic stability, poor health care access, non-Hispanic Blacks, poor health risk behaviors, were significantly associated with poor general, mental, or physical HRQOL. Lack of physical activity and less health care access (i.e., less frequent health checkups) were the major SBDH factors of poor HRQoL in all three outcomes among GI cancer survivors.

Our study is one of the few studies examining the HRQoL in different GI cancer types. Our analyses showed significant evidence of GI cancer-type differences in HRQoL (general, and physical outcomes). Notably, GI cancer survivors diagnosed with esophageal, liver, pancreatic, and stomach cancers more likely reported poor general and physical HRQoL, compared to colorectal cancer survivors. One possibility is a higher cancer burden in certain GI cancer types compared to colorectal cancer. For example, liver and pancreatic cancers generally have a poor prognosis and are often diagnosed at advanced stages with high mortality rates [

11]. Furthermore, this can be due to the better prognosis of colorectal cancer compared to live or pancreatic cancer as the early screening and diagnosis of colorectal cancer are well established [

28]. Interestingly, the older adults (65 years or older) reported better general and mental HRQoL, but not physical HRQoL in our study. This could be due to the fact that older adults are capable of higher resilience and more capable of managing or resolving conflicts, despite socioeconomic status, and personal health conditions; or older adults in the retirement stage might have fewer responsibilities, dealing with more major life events, compared to those of younger adults (18-64 years old) [

29]. It is important to identify different risk factors that contribute to HRQoL between younger and older age groups, which can provide age-tailored cancer survivorship interventions.

In our study, non-Hispanic Black and other racial and ethnic groups (e.g., Asian, Native Hawaiian, and other Pacific Islander, Multiracial) had a higher prevalence of reporting poor general HRQoL at 22.7%, compared to 17% who reported better general HRQoL (p <.001). Similarly, in a large sample case-control, population-based study from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) study, non-Hispanic White cancer survivors had better HRQoL scores than Black cancer survivors and Hispanics in the U.S. [

30]. This might be due to the structural racism that exists in the U.S. including in the healthcare system, which could result in poor health care access, low health literacy, disparities in cancer survivorship care, disparities in treatment options and quality of care, disparities in cancer stages, comorbidity burden, socioeconomic status, insurance coverage, and lack of community resources and policy support [

30]. Consistent with previous research [15, 30], we observed that married/partnered, high-income status, high educational levels, owning a home, frequent health care access, and optimal health behaviors were associated with better HRQoL outcomes. Marital status, which is often used as a proxy of social support, was significantly related to better general and mental HRQoL [

31]. Future studies should explore the influence of structural racism and social support on HRQoL outcomes [

32].

In GI cancer survivors, we also showed that current engagement in physical activity was the most impactful factor related to better HRQoL outcomes after analyzing various risk factors in our study. Numerous studies have demonstrated significant associations between physical activity and better mental and physical HRQoL among cancer survivors [33, 34]. The mechanisms through which physical activity improves the HRQoL are unknown. One explanation could be symptoms such as fatigue and psychological distress acting as a mediator between physical activity and HRQoL in cancer survivors [5, 35, 36]. Other potential mechanisms that could explain the link between P.A. and HRQoL are systemic inflammation, the release of endorphins, or by blocking or diminishing external or internal forces that cause stress in cancer survivors [37-39]. We did not find a significant association between daily fruit and vegetable consumption and HRQoL in the adjusted models. It is possible that daily fruit and vegetable consumption may not be a sufficient measure for diet, or fully reflect the nutritional status (including diet quality and food groups), which is significantly associated with the risk of GI cancers and cancer survivorship [

40]. Other health risk behaviors including smoking status and alcohol habits were also associated with HRQoL. These health risk behaviors increase the risk of cancer recurrence, and poor disease progress in cancer survivors in the long term [

41].

These findings have important implications for clinical practice and public health interventions. Our findings suggest that lifestyle interventions (specifically targeting physical activity) and the screening and, prevention of health risk behaviors as well as the promotion of healthy behaviors must be an integral part of cancer survivorship care. For example, healthcare providers should emphasize the importance of physical activity and smoking cessation for GI cancer survivors and consider referral to functional or mental health rehabilitation for those with poor mental or physical HRQoL. Policymakers should consider supporting a community-based cancer survivorship program. The findings of our study could be leveraged to develop a machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (A.I.)-based predictive model of HRQoL. These models could incorporate data on demographics, clinical characteristics, and SBDH risk factors to identify patients at risk of poor HRQoL and inform personalized interventions to improve their HRQoL. Furthermore, these models could help identify factors most strongly associated with HRQoL, which could inform the development of more effective interventions.

The study strengths include utilizing the BRFSS data as a reliable data source, with national representation to increase the generalizability of the research findings [

25]. The BRFSS survey also used reliable and validated instruments within samples, which increases the consistency of the measures and generalizability and reduces data collection bias. Our study adds to the body of literature by identifying risk factors of poor HRQoL in three HRQoL outcomes with a primary focus on the roles of SBDH, specific to GI cancer survivors. There are limitations to our study. Our study is limited by the cross-sectional nature of the data, which limits our ability to establish causality. For example, whether poor SDOH status mediates the relationships between racial and ethnic minorities and poor HRQoL, or whether poor SDOH status increases the likelihood of developing chronic conditions, which, in turn, can negatively impact HRQoL. Self-reported HRQoL data may be subject to reporting bias. Symptoms (particularly fatigue, psychological distress, and GI symptoms), as well as dietary factors like, red meat consumption and the amount of fruits and vegetables consumed, have been found to be associated with HRQoL in GI cancer survivors. However, these variables were not examined in the current study. Additionally, other SBDH factors such as poverty level, neighborhood and environmental factors, and social support level data were not available in our study. This lack of inclusion limits the comprehensive understanding of the impact of these factors on the HRQoL of GI cancer survivors. We also could not adjust for cancer stages, or types of cancer treatments (e.g., radiation, chemotherapy, or surgery) associated with HRQoL in GI cancer survivors [

20].

5. Conclusions

Our findings provide valuable insights into the SBDH as well as demographic and clinical characteristics that may influence HRQoL among GI cancer survivors in the U.S. The results of our study highlight the important role of age, comorbidities, and type of GI cancers (non-colorectal cancer) on HRQoL. In addition, multiple SBDH including low economic stability, unemployment, poor health care access, smoking and alcohol health risk behaviors, and lack of physical activity contribute to poor HRQoL among GI cancer survivors. Thus, future studies are warranted to consider the comprehensive assessment of HRQoL and to develop and test tailored cancer survivorship interventions for GI cancer survivors at a high risk of developing poor HRQoL, particularly for underserved and racial and ethnic minority populations with social or economic disadvantages, and ML/AI approaches could be one strategy to help improve the HRQoL of this group of GI cancer survivors.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation was performed by Claire Han and reviewed by all authors. Claire Han (first author) and Fode Tounkara conducted primary data analyses. Claire Han wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors commented on previous versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have reviewed, discussed, and agreed to their individual contributions ahead of this time. Conceptualization: Claire Han, Fode Tounkara. Data curation, and analysis: Claire Han, Fode Tounkara. Methodology, Study Design, Writing Original Draft: Claire Han, Diane Von Ah, Natasha Burse, Fode Tounkara. Supervision: Claire Han, Diane Von Ah. Writing: review and editing: Claire Han, Diane Von Ah, Natasha Burse, Electra Paskett, Matthew Kalady, Ann Noonan

Funding

The work was original research that had not been published previously. Claire Han: Cancer Research Seed Grant from the Ohio State University College of Nursing and the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center. Natasha Burse was funded by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K00CA253762. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

For this current study, we used a secondary analysis of the BRFSS survey data that is publicly available. Thus, the institutional review board (IRB) waived approval for this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study from the original BRFSS surveys. In the BRFSS original study, written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey data and the questionnaires are publicly available to researchers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Arnold, M.; et al. , Global Burden of 5 Major Types of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Gastroenterology, 2020, 159, 335-349.e15. [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program Populations (1969-2020), 2022. www.seer.cancer.gov/popdata (accessed 2023-June-1).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health-related quality of life (HRQOL), 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/index.html (accessed 2023-May-23).

- Tantoy, I.Y.; et al. ., A Review of the Literature on Multiple Co-occurring Symptoms in Patients With Colorectal Cancer Who Received Chemotherapy Alone or Chemotherapy With Targeted Therapies. Cancer Nurs, 2016, 39(6), 437-445. [CrossRef]

- Han, C.J. ; G.S. Yang, and K. Syrjala, Symptom Experiences in Colorectal Cancer Survivors After Cancer Treatments: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs, 2020, 43, E132-e158. [CrossRef]

- Han, C.J.; et al. , Symptom Clusters in Patients With Gastrointestinal Cancers Using Different Dimensions of the Symptom Experience. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2019, 58(2), 224-234. [CrossRef]

- Han, C.J.; et al. , Stability of Symptom Clusters in Patients With Gastrointestinal Cancers Receiving Chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2019, 58, 989-1001.e10. [CrossRef]

- Firkins, J.; et al. , Quality of life in “chronic” cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. J Cancer Survive. 2020, 14, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sipaviciute, A.; et al. , Late gastrointestinal toxicity after radiotherapy for rectal cancer: a systematic review. Int J Colorectal Dis, 2020, 35(6), 977-983. [CrossRef]

- Ashktorab, H.; et al. , Racial Disparity in Gastrointestinal Cancer Risk. Gastroenterology, 2017, 153, 910-923. [CrossRef]

- Bui, A.; et al. , Racial and ethnic disparities in incidence and mortality for the five most common gastrointestinal cancers in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc, 2022, 114, 426-429. [CrossRef]

- LeMasters, T.; et al. , A population-based study comparing HRQoL among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors to propensity score matched controls, by cancer type, and gender. Psycho-Oncology, 2013, 22, 2270-2282. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.K. and A. Jemal, Socioeconomic and Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Cancer Mortality, Incidence, and Survival in the United States, 1950-2014: Over Six Decades of Changing Patterns and Widening Inequalities. J Environ Public Health, 2017, 2819372. [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, L.C.; et al. , Social determinants of health and cancer mortality in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort study. Cancer, 2022, 128, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burse, N.R.; et al. , Influence of social and behavioral determinants on health-related quality of life among cancer survivors in the USA. Support Care Cancer, 2022, 31, 67. [CrossRef]

- Santee, E.J.; et al. , Health Care Access and Health Behavior Quality of Life among Hispanic/Latino-American Cancer Survivors. App Res Qual Life, 2020, 15, 637-650. [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, S.S. ; Social determinants of breast cancer risk, stage, and survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2019, 177, 537-548. [CrossRef]

- Oberguggenberger, A.; et al. , Health Behavior and Quality of Life Outcome in Breast Cancer Survivors: Prevalence Rates and Predictors. Clin Breast Cancer, 2018, 18, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.W. and T.N.M. Hua, Impact of Lifestyle Behaviors on Cancer Risk and Prevention. J Lifestyle Med, 2021, 11, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Marco, D.J.T. and V.M. White, The impact of cancer type, treatment, and distress on health-related quality of life: cross-sectional findings from a study of Australian cancer patients. Support Care Cancer, 2019; 27, 3421–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierannunzi, C. ; S.S. Hu, and L. Balluz, A systematic review of publications assessing reliability and validity of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2004–2011. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2013, 13, 49. [CrossRef]

- 22. Casebeer AW, Antol DD, Hopson S, et al. Using the Healthy Days Measure to Assess Factors Associated with Poor Health-Related Quality of Life for Patients with Metastatic Breast, Lung, or Colorectal Cancer Enrolled in a Medicare Advantage Health Plan. Popul Health Manag, 2019; 22, 440–448. [CrossRef]

- 23. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Social determinants of health. Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health (accessed on 5 April 2023).

-

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Alcohol and Public Health. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/index.htm (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Iachan, R.; et al. , National weighting of data from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system (BRFSS). BMC Med Res Methodol, 2016; 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatcheva, K.P.; et al. Multicollinearity in regression analyses conducted in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology (Sunnyvale, Calif. 2016; 6, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.Z.I. and T. C. Turin, Variable selection strategies and its importance in clinical prediction modelling. Family medicine and community health, 2020, 8, e000262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoskins, B.; et al. , Screening strategy for gastrointestinal and hepatopancreatobiliary cancers in cystic fibrosis. World J Gastrointest Oncol, 2021, 13, 1121-1131. [CrossRef]

- MacLeod S, Musich S, Hawkins K, Alsgaard K, Wicker ER. The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2016, 37, 266–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, L.C.; et al. , The effects of cancer and racial disparities in health-related quality of life among older Americans: A case-control, population-based study. Cancer, 2015; 121, 1312–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Saenz de Tejada, M.; et al. , Association between social support, functional status, and change in health-related quality of life and changes in anxiety and depression in colorectal cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 2017; 26, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala, V.A.; et al. , Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer, 2021, 124, 315-332. 124. [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.M.; et al. , Physical activity, confidence and quality of life among cancer patient-carer dyads. Sports Med Open, 2021; 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.L.; et al. , Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2019, 51, 2375-2390. [CrossRef]

- Bouillet, T.; et al. , Role of physical activity and sport in oncology: scientific commission of the National Federation Sport and Cancer CAMI. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2015, 94, 74-86. [CrossRef]

- Serra MC, Ryan AS, Ortmeyer HK, Addison O, Goldberg AP. Resistance training reduces inflammation and fatigue and improves physical function in older breast cancer survivors. . Menopause, 2018; 25, 211–216. [CrossRef]

- LaVoy, E.C. ; C.P. Fagundes, and R. Dantzer, Exercise, inflammation, and fatigue in cancer survivors. Exerc Immunol Rev, 2016, 22, 82-93.

- Diggins, A.D.; et al. , Physical activity in Black breast cancer survivors: implications for quality of life and mood at baseline and 6-month follow-up. Psycho-Oncology, 2017; 26, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himbert, C.; et al. , Associations of Individual and Combined Physical Activity and Body Mass Index Groups with Proinflammatory Biomarkers among Colorectal Cancer Patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2022, 31, 2148-2156. 31. [CrossRef]

- Moazzen S, Cortes-Ibañez FO, van der Vegt B, Alizadeh BZ, de Bock GH. Diet quality indices and gastrointestinal cancer risk: results from the Lifelines study. Eur J Nutr, 2022, 61, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez V, Klainin-Yobas P. Health Promotion Among Cancer Patients: Innovative Interventions. 2021 Mar 12. In: Haugan G, Eriksson M, editors. Health Promotion in Health Care – Vital Theories and Research [Internet]. Cham (CH): Springer; 2021. Chapter 17. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).