1. Introduction

According to recent literature, a significant proportion of young females and males worldwide suffer from eating disorders (EDs), with trends increasing over time [

1,

2,

3] .EDs that fulfill DSM-5 diagnostic criteria [

4], such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, are only a part of a broader spectrum of eating disturbances [

5]. Disordered eating behaviours (DEBs) refer to abnormal eating behaviours that do not meet the criteria for diagnosis of ED, such as restrictive dieting and other extreme weight-control methods [

6]. Prevalence of DEBs is higher than the prevalence of EDs according to studies in different countries and in different populations [

3,

7,

8,

9].

Adolescence is considered a high-risk period for the development of EDs and DEBs [

10]. A recent systematic review of 32 studies including 63181 participants indicated that 22% of children and adolescents present DEBs, with elevated prevalence among girls, older adolescents and those with higher body mass index [

11]. The consequences of these behaviours are serious, as adolescence is marked by major changes in body composition, metabolic and hormonal function, organ maturation, and nutritional deposit formation, all of which may have an impact on future health [

12]. Moreover, many of the dietary habits that are learned during adolescence persist throughout adult life, thus it is very likely for an adolescent with DEBs to continue suffering from DEBs or even progressing in the development of EDs in his/her adulthood [

13].

Risk factors for the development of EDs and DEBs during adolescence are multiple and include genetics, physiology, developmental issues, social influences, family characteristics and personality traits [

14]. It has been indicated that the family can play a role in the development and maintenance of eating disorders; however family factors should not be considered as the exclusive or even the primary mechanisms that underlie risk, as EDs are multifactorial diseases [

15].

An association between parenting styles and DEBs of adolescents has been reported. Specifically, a recent review indicated that adverse parenting styles, characterized by high demandingness, low responsiveness and high levels of control are directly and indirectly linked with greater risk of DEBs’ development in adolescents [

16]. Negative parental comments relative to weight and body shape have also been studied. A recent Australian study found that perceived negative comments from parents are linked to poorer adolescent mental health and disordered eating behaviours [

17]. Associations have also been found between young adults’ DEBs and negative weight and body shape comments by the parents, parental encourangement to lose weight and parental messages about the importance of being thin [

18,

19,

20]. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that families should promote a positive body image among adolescents and they should not talk about weight or encourage adolescents to diet, in order to prevent the development of eating disorders [

21]. Nevertheless, the percentage of adolescents that report parental comments regarding weight or eating behaviours seems to be high, ranging from 12% to 76% [

22].

Moreover, adolescents’ dietary habits are influenced by their parents’ attitudes and practices, even if the former seem to demand autonomy in their nutrition [

23]. Parents may have a significant impact on adolescents' eating behaviors, as they act as models of good or bad dietary habits [

24]. According to Balantekin et al (2019), children copy their parents’ eating behaviours, meaning that if parents engange in restrictive diets or other unhealthy weight-control methods, their offspring can mimic them feeling that this is the right way to control their weight. Thus, parents can play a significant role in shaping their childrens’ disordered eating behaviours [

25]. Although a significant number of studies has examined the correlation between parental present or past eating disorder symptoms and adolescents’ DEBs [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31], specific parental eating habits have not been studied to great depth. An older study in New Zealand found an association between fathers’ and daughters’ dieting [

32], while an observational study on pre-adolescents found that girls whose mothers were dieting during the study period were significantly more likely to diet before the age of 11 [

33].

The present article aims to review the existing literature on the relationship between parental dieting practices, either reported by the parents or as perceived by their adolescents offspring, and disordered eating behaviours of adolescents. Specifically, the current review tries to explore if dieting, used by the parents as a weight-control method, has been studied as a specific behaviour that may be linked to the DEBs of adolescents. The review has focused only on the population of adolescents, as they are considered more vulnerable regarding the development of DEBs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

Three different databases (PubMeD/MEDLINE® (US National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA), Scopus (Elsevier, Netherlands) and Google Scholar (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA) were used for the electronic search of international literature, in order to track studies published from January 2000 until May 2023. In order to search for studies relevant to the topic of the review, the terms shown in

Table 1 were combined.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

In order to be included in the current review, articles should meet the criteria shown in

Table 2, while articles meeting the exclusion criteria were excluded from the review. All article abstracts were screened by three authors (I.K., S.S. and A.M.P.) working in a blinded fashion. The articles that didn’t comply with the inclusion criteria were removed. Any controversies were dealt with consensus in a meeting, in which the abstracts were reviewed.

3. Results

3.1. Eligible Studies

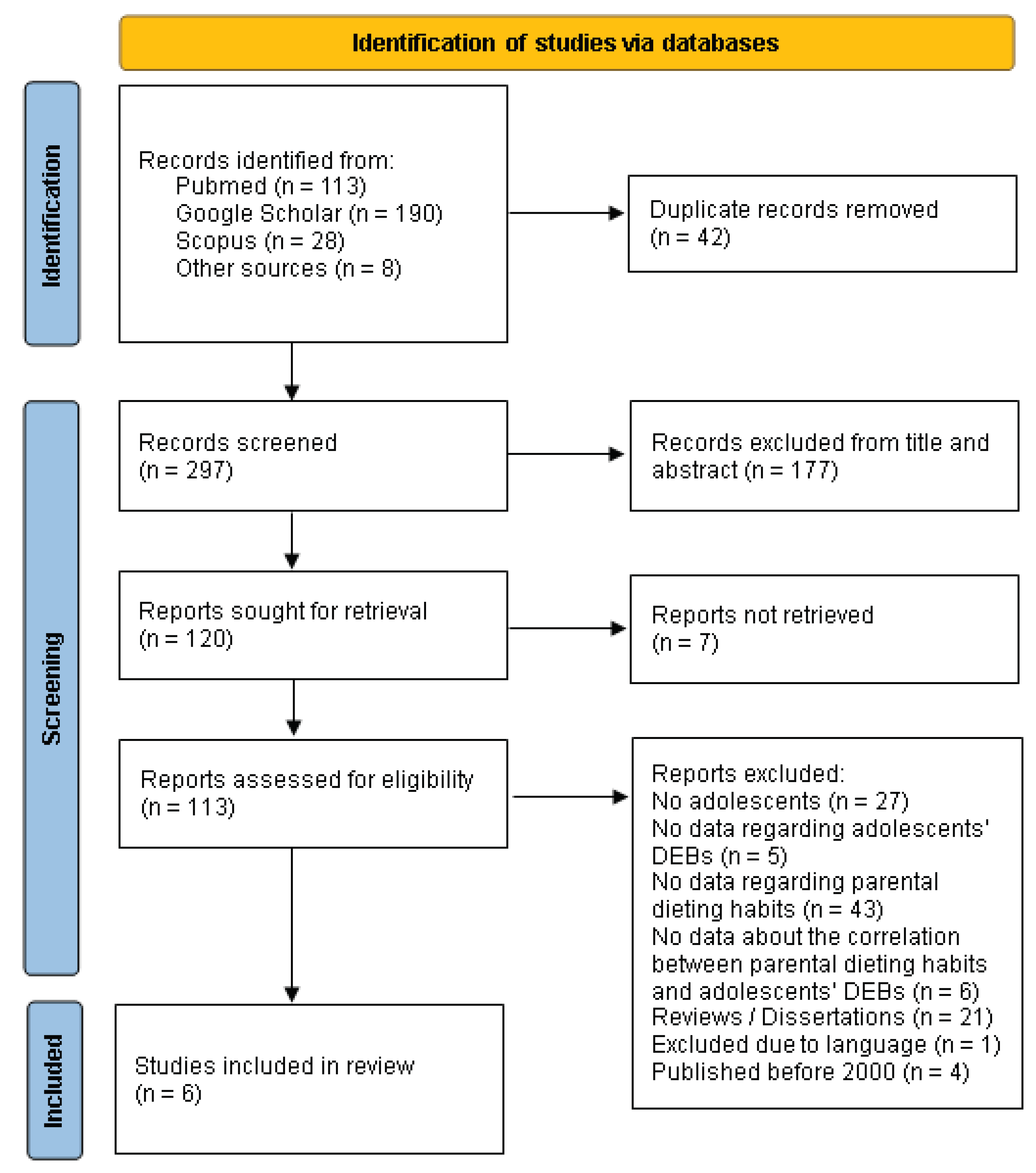

The initial database search retrieved 339 abstracts, of which 113 were retrieved from Pubmed, 190 from Google Scholar and 28 from Scopus, while 8 abstracts were found from other sources. After removing 42 duplicated articles, those remaining were screened and 177 articles were rejected based on their title and abstract, while 7 articles were not retrieved in full text. Subsequently, 113 full articles were evaluated for eligibility according to the inclusion criteria. One hundred and seven articles were excluded for various reasons according to the exclusion criteria. Therefore, 6 articles were selected for inclusion in the current review. The flow chart describing the sequential steps for selecting studies according to PRISMA 2020 [

34], is presented in

Figure 1.

3.2. Characteristics of Eligible Studies and Population

Four of the eligible studies were conducted in USA [

35,

36,

37,

38], 1 in Argentina [

39] and 1 in Greece [

40]. Three of the studies were cross-sectional [

36,

37,

40], while 1 study had case-control design [

39] and 2 had prospective cohort design [

35,

38]. The sample size of the studies ranged from 45 participants to 810 participants. In 3 studies, the participants were the adolescents that also provided data regarding their parents [

36,

38,

40]. In 2 studies only parents answered the questionnaires, as data regarding adolescents’ DEBs were obtained from clinicians [

35,

39], while in 1 study data were obtained by both the adolescents and their parents [

37]. In the majority of the studies both boys and girls took part, however the percentage of girls was higher, and 2 studies included only teenage girls [

36,

39]. Accordingly, in 3 studies only mothers were included [

37,

38,

39], while in 3 other studies both mothers and fathers took part [

35,

36,

40]. Regarding the adolescents’ DEBs, they were reported by psychiatric evaluation in 2 studies [

35,

39], by the EAT-26 screening tool in 1 study [

40] and by a questionnaire specifically designed for the studies in 3 of them [

36,

37,

38]. Finally, regarding parental dieting, 2 studies collected data using questionnaires answered by the parents themselves [

35,

39], in 3 studies parental dieting was reported as perceived by the adolescents [

36,

38,

40], and in 1 study, data regarding parental dieting was obtained by both the adolescents and their parents [

37].

3.3. Correlations between parental dieting and adolescents’ disordered eating behaviours

The main characteristics and findings of the 6 eligible studies are presented in

Table 3. The majority of the studies found a positive correlation between parental dieting and adolescents’ DEBs, but with many different aspects being examined. Bilali et al (2010) in a cross-sectional study on a sample of 540 adolescent students found an association between adolescent eating disorder and the perceived dieting of their parents. In this study 52% of adolescent boys and girls reported parental dieting, while DEBs were found in the 16.7% of the participants. According to the findings, teenagers who had a family member who was dieting were more likely to have disordered eating attitudes than those who did not. It was hypothesized that the presence of a dieting family member may signal greater worries about eating, dieting, and body image in adolescents [

40].

Similar results were found by Neumark-Sztainer et al (2010), where 75% of the adolescent girls reported maternal and approximately 40% paternal dieting. It was found that maternal dieting was related to unhealthy or extreme weight control behaviours on behalf of the adolescent, while paternal dieting was unrelated. When maternal and paternal contributions to teen problematic dietary behaviour were examined in combination, paternal influence was found irrelevant when the maternal influence was also taken into consideration. It is worth mentioning that parents talking about their own weight were also found to have negative effects on the adolescents’ dietary behaviour [

36].

Accordingly, Keery et al (2006) on a sample of 810 adolescent boys and girls and their mothers found that there is a positive association between maternal and child dietary concerns. This study evaluated maternal dieting as it was perceived by adolescents and also as it was reported by the mothers. An interesting finding was that the aforementioned positive association was significant only when maternal dieting as perceived by the adolescents was taken into account. On the other hand, self-reported maternal dieting revealed no significant correlation with either boys’ or girls’ reports of weight concerns or weight control behaviours. The results could indicate that the difference of perception between child and mother needs to be taken into consideration. The importance of proper communication between mothers and adolescents regarding the latter’s dietary choices and practices also emerges [

37].

Interesting findings have been reported by 2 studies that examined dieting as a characteristic of parents whose adolescents were admitted to ED clinics. Garcia de Amusquibar et al (2003) examined specific features between the mothers of adolescent patients who underwent ED consultation and those of a control group of mothers of healthy adolescents. One of the characteristics that was studied was dieting that was reported during the interview of the mother and also assessed by the mother’s score on the dieting scale of EAT-26 questionnaire. Similar maternal dieting percentages were found in the two groups, as 68% of the first group and 70% of the second one reported dieting at some point. Accordingly, 16% of the mothers of ED adolescents and 13.3% of the control group mothers had a high score in EAT-26 dieting scale. The aforementioned differences were not statistically significant [

39].

In a recent study, Duck et al (2023) examined the link between the outcomes of inpatient treatment for 45 adolescents with restrictive eating disorders and their parents’ dieting attitudes. One-third of parents reported that they were dieting at that time, while it was found that adolescents whose parents reported dieting, gained weight at a slower rate and had lower median body mass index percentiles at discharge, compared to adolescents whose parents were not dieting. Additionally, teens whose parents stated that their spouse was currently dieting had lower median body mass index percentiles at discharge. According to the researchers one explanation for the slower weight gain in those children is that dieting parents may have imparted on to them ideas about how important being slim is and anxieties about being overweight [

35].

Finally, Haynos et al (2016) prospectively evaluated the factors that contribute in the development of DEBs in a cohort of 243 adolescents that had reported dieting but not disordered restrictive eating in the initiation of the study. Mother’s dieting was one of the factors that predicted adolescent engagement in disordered eating 5 years later, indicating a positive correlation between child-reported maternal dieting and initiation of DEBs by the adolescent [

38].

4. Discussion

The scope of the present review is to present the available literature regarding the association between parental dieting and adolescents’ engagement in disordered eating begaviours. A significant finding of this review is that the study of this association is very scarce. Only 6 studies fullfiled the criteria to be included in the review, as the majority of the studies among adolescents with DEBs have not examined dieting as a specific parental behaviour. All but one of the included studies indicated a positive, but not strong, association between parental dieting and adolescents’ DEBs, although many details regarding this association should be discussed. First of all, it seems that there is a difference regarding the perspective of dieting as it is perceived by the adolescents and as it is reported by the parents, as indicated by Keery et al (2006) [

37]. Moreover, three more studies that found positive correlations used child-reported parental dieting as a factor [

36,

38,

40]. Therefore, it seems that the different perceptions should be taken into account in future studies, while the communication between parents and adolescents on dieting practices and the ideal of being thin should be further examined.

Another significant finding of the review is that mothers’ dieting behaviours have a significant influence on their adolescent children’s behaviours, but fathers’ behaviours are less studied. One study that examined both maternal and paternal dieting found that only mothers’ habits influenced adolescents’ DEBs, while no association was found with fathers’ habits [

36]. Furthermore, 2 more studies found a positive link with maternal dieting [

37,

38]. Even in the studies where both mothers and fathers participated, the percentage of mothers was significantly higher [

35,

36]. Dixon et al (1996), almost 30 years ago, indicated that paternal dieting predicted adolescent daughters’ DEBs [

32]. Dixon et al (2010), in a later study also found associations between fathers’ perception of the importance of women being slim and keeping control of their dietary intake and their adolescent daughters’ DEBs [

42]. Moreover, paternal dissatissfaction about his own weight, as well as paternal comments on daughter’s weight have been associated with daughters’ weight dissatisfaction [

43]. Finally, fathers’ influence in the developments of DEBs has also been studied regarding the relationship with their daughters. Paternal rejection and overprotection were found to predict aspects of eating psychopathology in their daughters [

44].

It is worth mentioning that one study showed that parental dieting is a factor that may negatively influence inpatient treatment outcomes for EDs, as it has been linked to a slower rate of weight gain [

35]. Even though there are not enough studies explaining how parental dieting may influence EDs treatment outcomes, it is advised that parents whose children are treated for EDs should follow a balanced diet and avoid any weight loss methods [

45]. Moreover, this findings bring out the necessity to include parents in the ED treatment protocols. ED health professionals should evaluate and advise parents regarding their own nutrition, as this may affect their children’s response to treatment.

Additionally, it should be discussed that, during the articles selection process, it was revealed that a significant number of studies has examined the association of parental eating disorder, that occurred in the past or it currently exists, and the development of adolescents’ DEBs. Many studies revealed that co-occuring eating disorder behaviours in parents are associated with greater adolescent eating disorder behaviours [

28,

30,

46,

47,

48]. Even the history of parental EDs acts as a risk factor for the development of DEBs in adolescents, especially when maternal past disordered eating is taken into account [

26,

27,

29,

39].

The main limitations of the current review emerge from the small number of included studies. Research regarding family risk factors for adolescents’ ED in the last 2 decades has focused on the direct influence of parents, such as the encouragement of children to diet and the comments for children's weight and body shape. Indirect influence has been studied, but mainly regarding the total disordered eating behaviours of the parents, such as their current or past eating disorder by using questionnaires that do not evaluate dieting separately [

25]. Moreover, a significant limitation is that there was no common method to obtain information regarding parental dieting. Some studies retrieved this information directly from the parents, while others included the perception of adolescents regarding their parent’s dieting behaviour. Additionally, the studies that examined parental dieting used only simple questions such as “Are you dieting currently?” and no validated questionnaires were used. Finally, as it has been previously discussed, parents that participate in these studies are mainly mothers, therefore more studies regarding the fathers’ role are needed.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, specific behaviours, such as frequent engagement of parents on weight-loss diets has not been thoroughly examined. According to the authors’ everyday clinical experience with adolescents with EDs and DEBs, many parents act as models of disordered eating behaviours for their children, and even if this is not the main risk factor for developing an ED, it could be considered as an important one. Therefore, we suggest the design of future studies regarding the association of specific parental dietary behaviours, such as dieting, and the development of DEBs in their children.

Mothers and fathers of adolescents should be informed and educated on the importance of avoiding unhealthy weight-control practices, including restrictive diets, in order to prevent the development of DEBs among their children. At the same time, they should be informed relatively to all the types of communication and influences that may increase the risk for their children to develop DEBs. For example, it has been indicated that weight-related conversations in the house are associated to unhealthy weight control behaviours by the adolescents, while when parents engage in healthful eating conversations, adolescents are less likely to practice unhealthy dietary behaviours [

49].

Parents who wish to prevent disordered eating by their children should focus on their own modeling healthy behaviours, i.e. abstaining from dieting and trying to follow a healthy balanced nutrition providing a variety of healthy food options, without restrictions and weight-related conversations. As the American Academy of Pediatrics indicates, in order to prevent weight related problems in adolescence, dieting should be discouraged, a positive body image should be promoted, families should be encouraged to implement healthy eating and physical activity behaviours, families should have frequent meals together and parents should avoid talking about weight but instead talk about healthy eating and being active to stay healthy [

21].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K. and T.V.; methodology, I.K.; investigation, I.K., S.S. and A.M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K., S.S. and A.M.P.; writing—review and editing, I.K., S.S., A.M.P., E.Z. and T.V.; visualization, I.K.; supervision, T.V.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr Spyros Tsevas for his contribution during the English editing of the manuscript

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Silén, Y.; Keski-Rahkonen, A. Worldwide Prevalence of DSM-5 Eating Disorders among Young People. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2022, 35, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galmiche, M.; Déchelotte, P.; Lambert, G.; Tavolacci, M.P. Prevalence of Eating Disorders over the 2000-2018 Period: A Systematic Literature Review. Am J Clin Nutr 2019, 109, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P.; Aouad, P.; Le, A.; Marks, P.; Maloney, D.; Barakat, S.; Boakes, R.; Brennan, L.; Bryant, E.; Byrne, S.; et al. Epidemiology of Eating Disorders: Population, Prevalence, Disease Burden and Quality of Life Informing Public Policy in Australia—a Rapid Review. Journal of Eating Disorders 2023, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8. [Google Scholar]

- Shisslak, C.M.; Crago, M.; Estes, L.S. The Spectrum of Eating Disturbances. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1995, 18, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stice, E.; Ng, J.; Shaw, H. Risk Factors and Prodromal Eating Pathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2010, 51, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancine, R.P.; Gusfa, D.W.; Moshrefi, A.; Kennedy, S.F. Prevalence of Disordered Eating in Athletes Categorized by Emphasis on Leanness and Activity Type - a Systematic Review. J Eat Disord 2020, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.B.; Blashill, A.J.; Calzo, J.P. Prevalence of Disordered Eating and Associations With Sex, Pubertal Maturation, and Weight in Children in the US. JAMA Pediatrics 2022, 176, 1039–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littleton, H.L.; Ollendick, T. Negative Body Image and Disordered Eating Behavior in Children and Adolescents: What Places Youth at Risk and How Can These Problems Be Prevented? Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2003, 6, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klump, K.L. Puberty as a Critical Risk Period for Eating Disorders: A Review of Human and Animal Studies. Horm Behav 2013, 64, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.F.; García-Hermoso, A.; Smith, L.; Firth, J.; Trott, M.; Mesas, A.E.; Jiménez-López, E.; Gutiérrez-Espinoza, H.; Tárraga-López, P.J.; Victoria-Montesinos, D. Global Proportion of Disordered Eating in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatrics 2023, 177, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Afifi, R.A.; Bearinger, L.H.; Blakemore, S.-J.; Dick, B.; Ezeh, A.C.; Patton, G.C. Adolescence: A Foundation for Future Health. The Lancet 2012, 379, 1630–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Wall, M.; Larson, N.I.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Loth, K. Dieting and Disordered Eating Behaviors from Adolescence to Young Adulthood: Findings from a 10-Year Longitudinal Study. J Am Diet Assoc 2011, 111, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, S.; McLean, S.A.; Bryant, E.; Le, A.; Marks, P.; Aouad, P.; Barakat, S.; Boakes, R.; Brennan, L.; Bryant, E.; et al. Risk Factors for Eating Disorders: Findings from a Rapid Review. J Eat Disord 2023, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- le Grange, D.; Lock, J.; Loeb, K.; Nicholls, D. Academy for Eating Disorders Position Paper: The Role of the Family in Eating Disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2010, 43, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampshire, C.; Mahoney, B.; Davis, S.K. Parenting Styles and Disordered Eating Among Youths: A Rapid Scoping Review. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahill, L.M.; Morrison, N.M.V.; Mannan, H.; Mitchison, D.; Touyz, S.; Bussey, K.; Trompeter, N.; Hay, P. Exploring Associations between Positive and Negative Valanced Parental Comments about Adolescents’ Bodies and Eating and Eating Problems: A Community Study. Journal of Eating Disorders 2022, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez, C.D. de L.; Santoncini, C.U. Parental Negative Weight/Shape Comments and Their Association with Disordered Eating Behaviors: A Systematic Review. Revista mexicana de trastornos alimentarios 2019, 10, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraczinskas, M.; Fisak, B.; Barnes, R.D. The Relation between Parental Influence, Body Image, and Eating Behaviors in a Nonclinical Female Sample. Body Image 2012, 9, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, M.E.; Berge, J.M.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Associations between Hurtful Weight-Related Comments by Family and Significant Other and the Development of Disordered Eating Behaviors in Young Adults. J Behav Med 2012, 35, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, N.H.; Schneider, M.; Wood, C. Preventing Obesity and Eating Disorders in Adolescents. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahill, L.; Mitchison, D.; Morrison, N.M.V.; Touyz, S.; Bussey, K.; Trompeter, N.; Lonergan, A.; Hay, P. Prevalence of Parental Comments on Weight/Shape/Eating amongst Sons and Daughters in an Adolescent Sample. Nutrients 2021, 13, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.S.N.; Chen, J.Y.; Ng, M.Y.C.; Yeung, M.H.Y.; Bedford, L.E.; Lam, C.L.K. How Does the Family Influence Adolescent Eating Habits in Terms of Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices? A Global Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, R.; Chabrol, H. Parental Attitudes, Body Image Disturbance and Disordered Eating amongst Adolescents and Young Adults: A Review. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2009, 17, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balantekin, K.N. The Influence of Parental Dieting Behavior on Child Dieting Behavior and Weight Status. Curr Obes Rep 2019, 8, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.L.; Gibson, L.Y.; McLean, N.J.; Davis, E.A.; Byrne, S.M. Maternal and Family Factors and Child Eating Pathology: Risk and Protective Relationships. J Eat Disord 2014, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bould, H.; Sovio, U.; Koupil, I.; Dalman, C.; Micali, N.; Lewis, G.; Magnusson, C. Do Eating Disorders in Parents Predict Eating Disorders in Children? Evidence from a Swedish Cohort. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2015, 132, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canals, J.; Sancho, C.; Arija, M.V. Influence of Parent’s Eating Attitudes on Eating Disorders in School Adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009, 18, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micali, N.; De Stavola, B.; Ploubidis, G.B.; Simonoff, E.; Treasure, J. The Effects of Maternal Eating Disorders on Offspring Childhood and Early Adolescent Psychiatric Disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2014, 47, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerberg, J.; Edlund, B.; Ghaderi, A. A 2-Year Longitudinal Study of Eating Attitudes, BMI, Perfectionism, Asceticism and Family Climate in Adolescent Girls and Their Parents. Eat Weight Disord 2008, 13, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziobrowski, H.N.; Sonneville, K.R.; Eddy, K.T.; Crosby, R.D.; Micali, N.; Horton, N.J.; Field, A.E. Maternal Eating Disorders and Eating Disorder Treatment Among Girls in the Growing Up Today Study. Journal of Adolescent Health 2019, 65, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.; Adair, V.; O’Connor, S. Parental Influences on the Dieting Beliefs and Behaviors of Adolescent Females in New Zealand. J Adolesc Health 1996, 19, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffman, D.L.; Balantekin, K.N.; Savage, J.S. Using Propensity Score Methods To Assess Causal Effects of Mothers’ Dieting Behavior on Daughters’ Early Dieting Behavior. Child Obes 2016, 12, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duck, S.A.; Guarda, A.S.; Schreyer, C.C. Parental Dieting Impacts Inpatient Treatment Outcomes for Adolescents with Restrictive Eating Disorders. European Eating Disorders Review 2023. [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Bauer, K.W.; Friend, S.; Hannan, P.J.; Story, M.; Berge, J.M. Family Weight Talk and Dieting: How Much Do They Matter for Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating Behaviors in Adolescent Girls? J Adolesc Health 2010, 47, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keery, H.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Boutelle, K.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M. Relationships between Maternal and Adolescent Weight-Related Behaviors and Concerns: The Role of Perception. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2006, 61, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynos, A.F.; Watts, A.W.; Loth, K.A.; Pearson, C.M.; Neumark-Stzainer, D. Factors Predicting an Escalation of Restrictive Eating During Adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health 2016, 59, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Amusquibar, A.M.; De Simone, C.J. Some Features of Mothers of Patients with Eating Disorders. Eat Weight Disord 2003, 8, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilali, A.; Galanis, P.; Velonakis, E.; Katostaras, T. Factors Associated with Abnormal Eating Attitudes among Greek Adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav 2010, 42, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Amusquibar. Some Features of Mothers of Patients with Eating Disorders.Pdf.

- DIXON, R.S.; GILL, J.M.W.; ADAIR, V.A. Exploring Paternal Influences on the Dieting Behaviors of Adolescent Girls. Eating Disorders 2003, 11, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keel, P.K.; Heatherton, T.F.; Harnden, J.L.; Hornig, C.D. Mothers, Fathers, and Daughters: Dieting and Disordered Eating. Eating Disorders 1997, 5, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horesh, N.; Sommerfeld, E.; Wolf, M.; Zubery, E.; Zalsman, G. Father–Daughter Relationship and the Severity of Eating Disorders. European Psychiatry 2015, 30, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS UK Advice for Parents – Eating Disorders. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/feelings-symptoms-behaviours/behaviours/eating-disorders/advice-for-parents/ (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- Boswell, R.G.; Lydecker, J.A. Double Trouble? Associations of Parental Substance Use and Eating Behaviors with Pediatric Disordered Eating. Addict Behav 2021, 123, 107089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, M.D.G.; Pina, J.A.L.; Ortuño, A.I.T.; Durán, A.L.; Trives, J.J.R. Parental Eating Disorders Symptoms in Different Clinical Diagnoses. Psicothema 2018, 30, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linville, D.; Stice, E.; Gau, J.; O’Neil, M. Predictive Effects of Mother and Peer Influences on Increases in Adolescent Eating Disorder Risk Factors and Symptoms: A 3-Year Longitudinal Study. Int J Eat Disord 2011, 44, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berge, J.M.; MacLehose, R.; Loth, K.A.; Eisenberg, M.; Bucchianeri, M.M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Parent Conversations about Healthful Eating and Weight: Associations with Adolescent Disordered Eating Behaviors. JAMA Pediatr 2013, 167, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).