Submitted:

07 July 2023

Posted:

10 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Genomic Data Sets

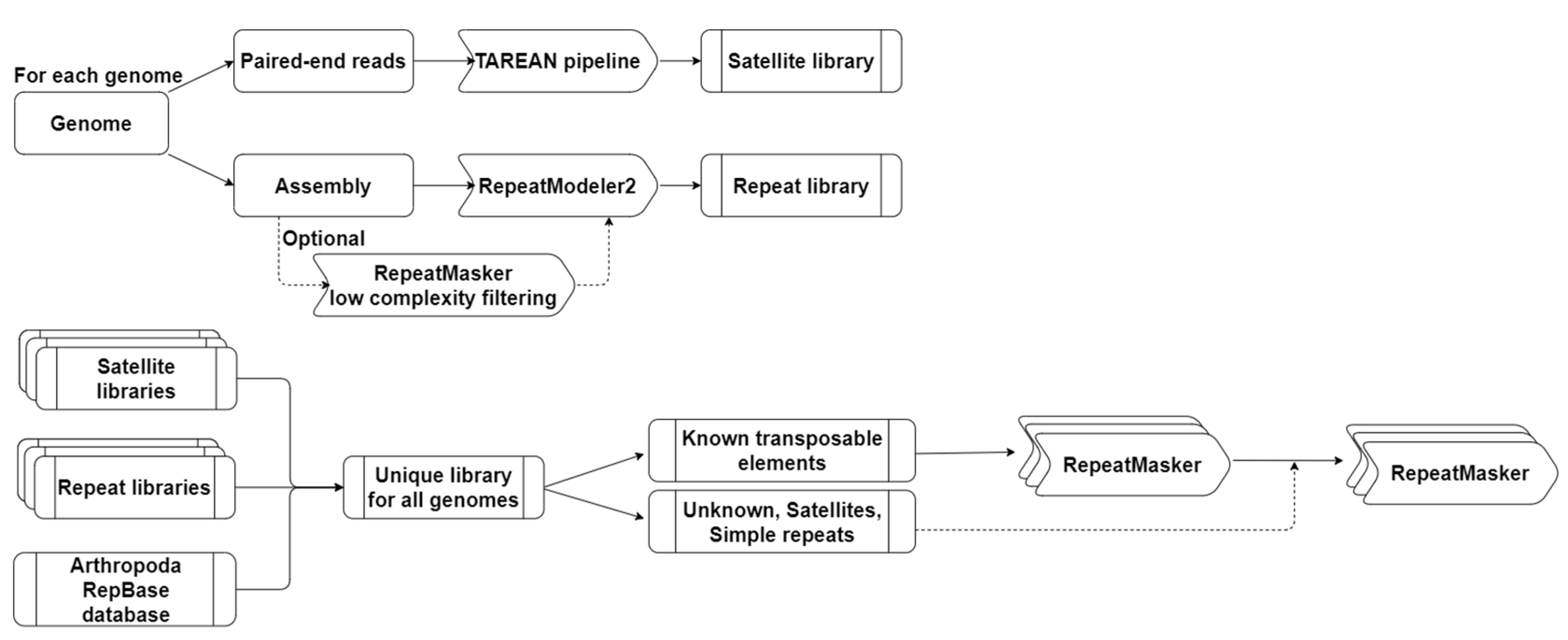

2.2. Identification and Annotation of Repetitive Elements

2.2.1. Identification of Satellite DNA Families

2.2.2. Construction of a Common Library of Repetitive Elements

| Suborder/ Infraorder | Species | Assembly Access ID | Assembly Size (Mb) | BUSCO Completeness (%) | Paired-End Illumina Reads SRA Access ID | Estimate Genome Size (Mb) | Estimate Genome Size Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dendrobranchiata | Penaeus chinensis | GCF019202785.1 | 1 466 | 90.7 | SRR13452153 | 2 660 | [48] |

| Penaeus indicus | GCA018983055.1 | 1 936 | 88.5 | SRR12969543 | 2 810 | [49] | |

| Penaeus japonicus | GCF017312705.1 | 1 705 | 96.6 | DRR278744 | 2 170 | [49] | |

| Penaeus monodon | GCF015228065.1 | 2 394 | 83.9 | SRR11278066 | 2 200 | [49] | |

| Penaeus vannamei | GCF003789085.1 | 1 664 | 84.8 | SRR13661692 | 2 270 | [49] | |

| Caridea | Caridina multidentata | GCA002091895.1 | 1 949 | 25.2 | DRR054559 | 3 230 | [50] |

| Macrobrachium nipponense | GCA015104395.1 | 1 985 | 41 | SRR9026393 | 4 600 | [51] | |

| Achelata | Panulirus ornatus | GCA018397875.1 | 1 926 | 70 | SSR13822589 | 3 230 | [52] |

| Astacidea | Procambarus virginalis | GCA020271785.1 | 3 701 | 67 | SRR12901906 | 3 500 | [53] |

| Procambarus clarkii | GCF020424385.1 | 2 735 | 94.3 | SRR14457195 | 8 500 | [54] | |

| Cherax destructor | GCA009830355.1 | 3 337 | 81.7 | SRR10467055 | 4 500 | [55] | |

| Cherax quadricarinatus | GCA009761615.1 | 3 237 | 69.9 | SRR10484712 | 5 000 | [56] | |

| Homarus americanus | GCF018991925.1 | 2 292 | 93 | SRR12699166 | 7 700 | [57] | |

| Anomura | Paralithodes camtschaticus | GCA018397895.1 | 3 810 | 44.2 | SRR13805857 | 7 290 | [52] |

| Paralithodes platypus | GCA013283005.1 | 4 805 | 71.7 | SRR1145749 | 5 490 | [58] | |

| Birgus latro | GCA018397915.1 | 2 959 | 57.7 | SRR13816158 | 6 220 | [52] | |

| Brachyura | Chionoecetes opilio | GCA016584305.1 | 2 003 | 91 | SRR11278230 | 1 655 | |

| Eriocheir sinensis | GCA013436485.1 | 1 272 | 92.6 | SRR11971329 | 2 230 | [59] | |

| Portunus trituberculatus | GCF017591435.1 | 1 005 | 93.5 | SRR9964028 | 2 250 | [59] | |

| Callinectes sapidus | GCA020233015.1 | 998 | 90.4 | SRR15834103 | 2 290 | [60] | |

| Other crustaceans | Amphibalanus Amphitrite (Cirripedia) | GCA019059575.1 | 808 | 93.9 | SRR9595623 | 481 | [61] |

| Armadillidium vulgare (Isopoda) | GCA004104545.1 | 1 725 | 84.5 | SRR8156178 | 1 660 | [62] | |

| Daphnia magna(Phyllopoda) | GCA020631705.2 | 161 | 98.6 | SRR15012074 | 238 | [63] | |

| Darwinula stevensoni (Podocopida) | GCA905338385.1 | 382 | 90.3 | SRR8695251 | 437 | [64] | |

| Eurytemora affinis(Copepoda) | GCA000591075.2 | 389 | 91 | SRR2452640 | 616 | [65] | |

| Hyalella Azteca(Amphipoda) | GCA000764305.4 | 551 | 93.8 | SRR1556043 | 1 050 | [66] |

2.2.3. Identification of Repetitive Elements

2.2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Construction of Repetitive Elements reference

3.2. Annotation of Repetitive Elements in Decapoda Genomes

3.3. Proportion of Repetitive Elements in Decapoda Genomes

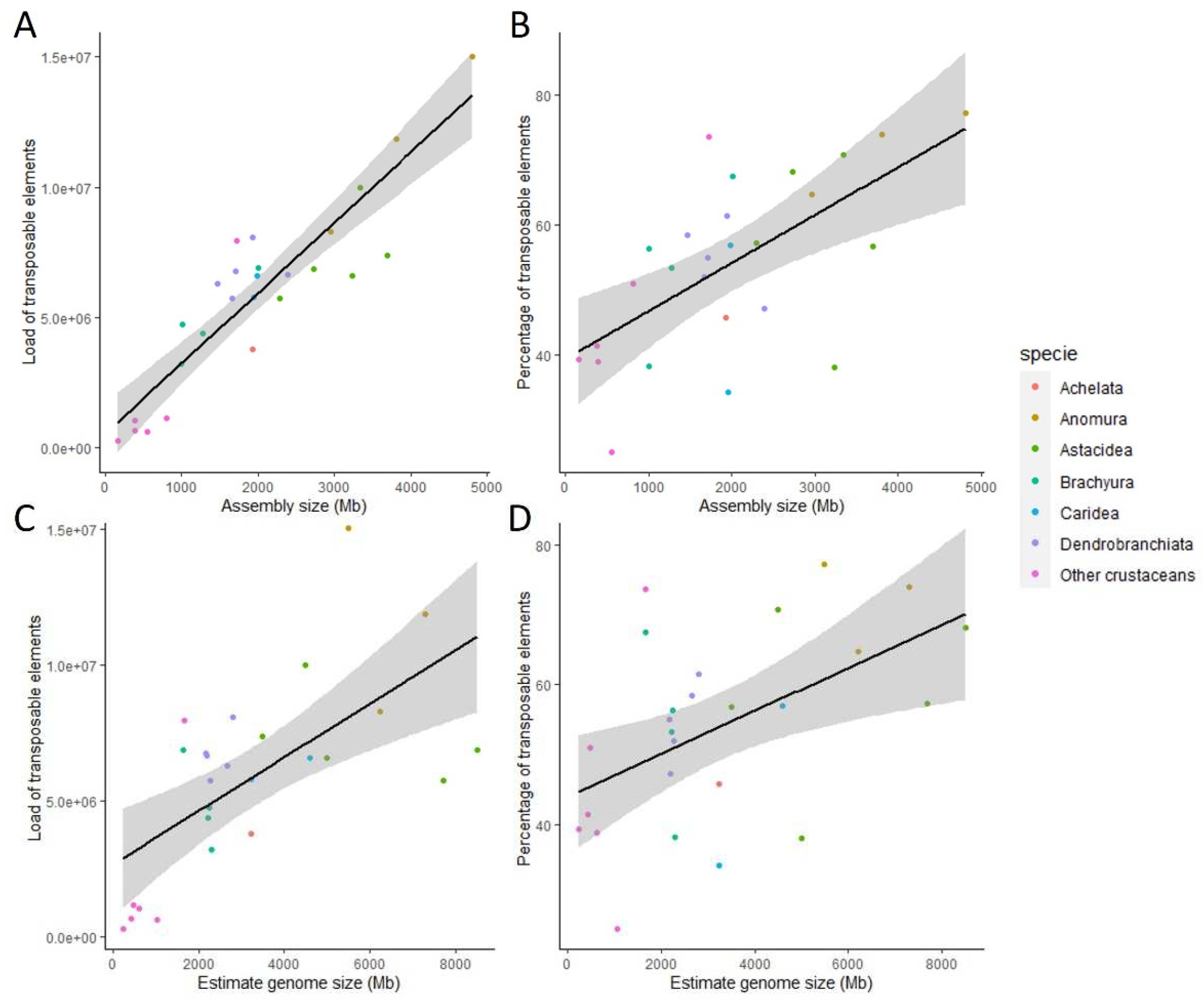

3.4. Correlation between Genome Size and Repetitive Elements

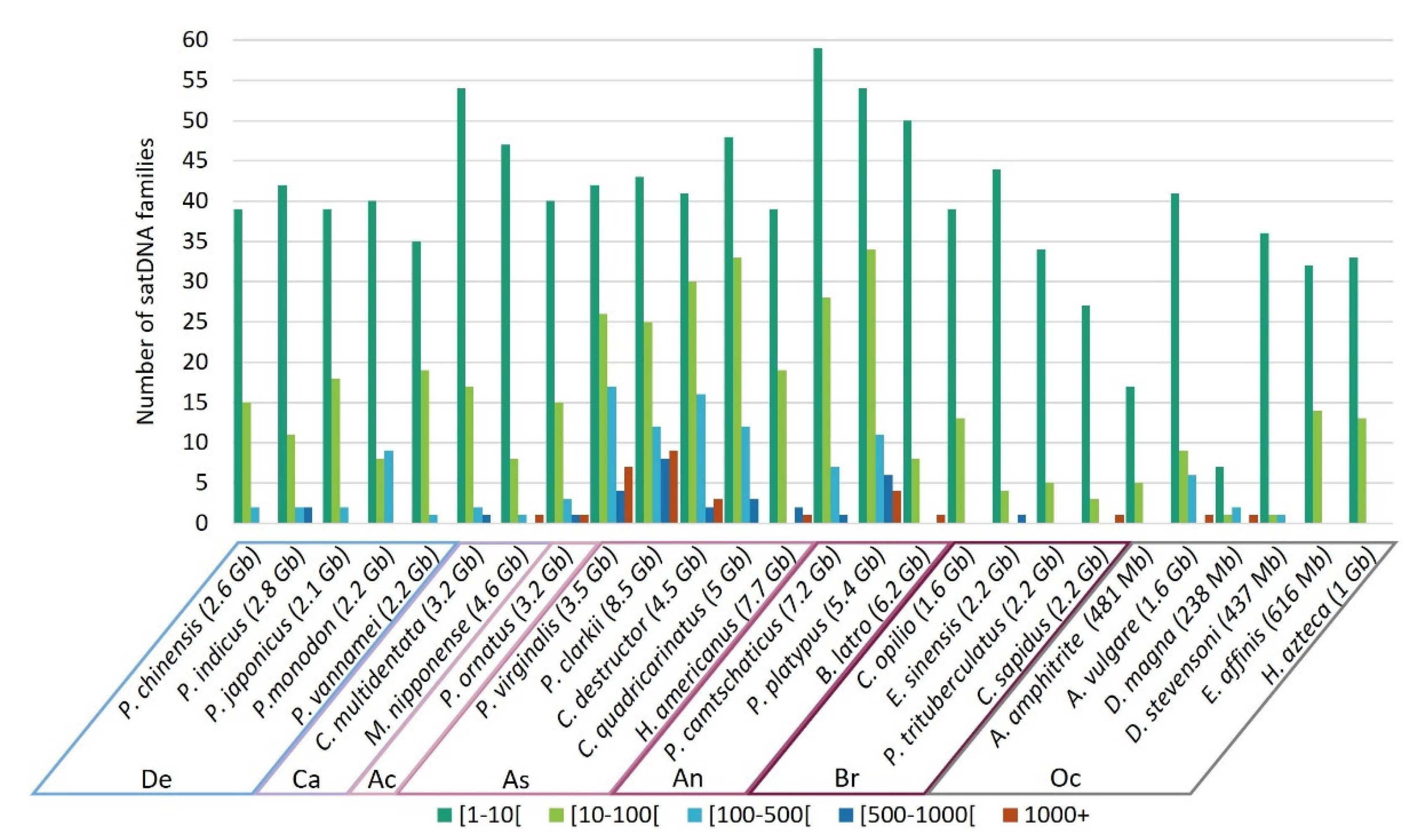

3.5. Frequency of satDNA Families Occurrence

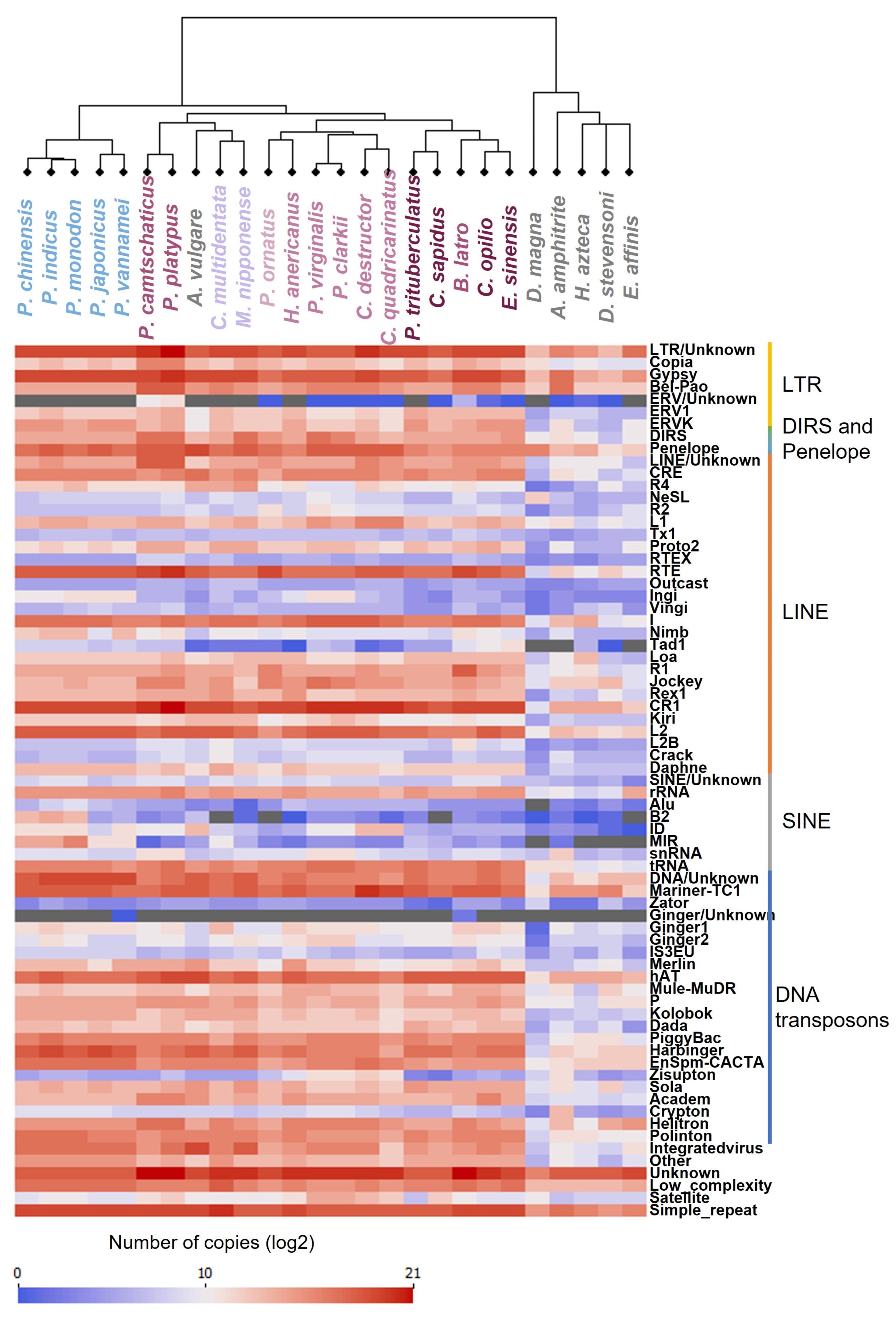

3.6. Diversity of Repetitive Elements

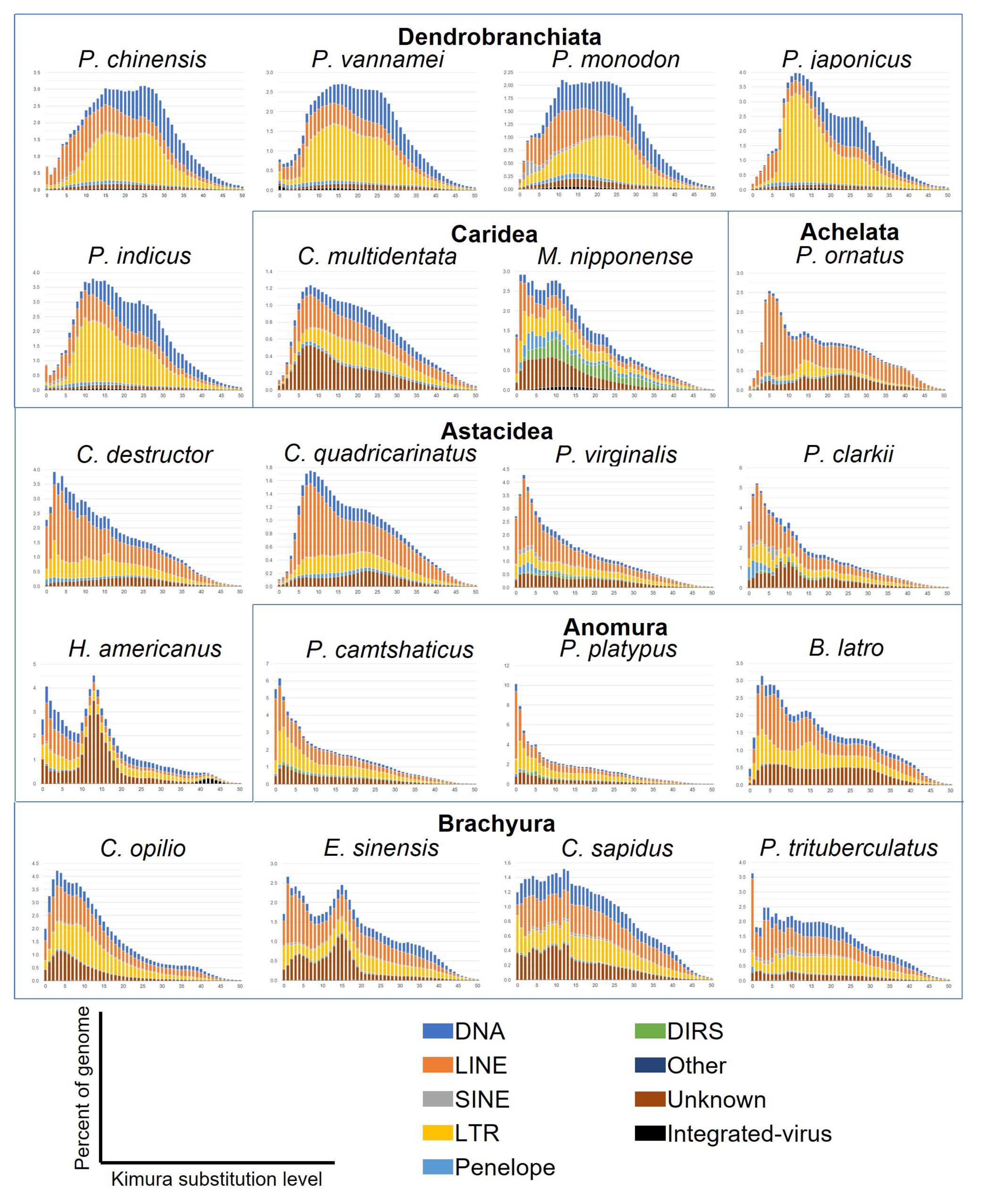

3.7. Sequence Divergence Distribution of Transposable Elements

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Grave S, Pentcheff ND, Ahyong ST, Chan T-Y, Crandall KA, Dworschak PC, et al. A Classification of Living and Fossil Genera of Decapod Crustaceans. 2009.

- Reynolds J, Souty-Grosset C, Richardson A. Ecological Roles of Crayfish in Freshwater and Terrestrial Habitats. Freshw Crayfish. 2013;19:197–218.

- Souty-Grosset C, Holdich DDM, Noël PY, Reynolds J, Haffner P. Atlas of crayfish in Europe. 2006. /paper/Atlas-of-crayfish-in-Europe.-Souty-Grosset-Holdich/148876f73785f0a4f00c2d17069a618b85250bcf. Accessed 2 Jun 2020.

- Wolfe JM, Breinholt JW, Crandall KA, Lemmon AR, Lemmon EM, Timm LE, et al. A phylogenomic framework, evolutionary timeline and genomic resources for comparative studies of decapod crustaceans. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2019;286:20190079. [CrossRef]

- Boštjančić LL, Bonassin L, Anušić L, Lovrenčić L, Besendorfer V, Maguire I, et al. The Pontastacus leptodactylus (Astacidae) Repeatome Provides Insight Into Genome Evolution and Reveals Remarkable Diversity of Satellite DNA. Front Genet. 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Lécher P, Defaye D, Noel P. Chromosomes and nuclear DNA of Crustacea. Invertebr Reprod Dev. 1995;27:85–114. [CrossRef]

- González-Tizón AM, Rojo V, Menini E, Torrecilla Z, Martínez-Lage A. Karyological Analysis of the Shrimp Palaemon Serratus (Decapoda: Palaemonidae). J Crustac Biol. 2013;33:843–8. [CrossRef]

- NIIYAMA H. On the Unprecedentedly Large Number of Chromosomes of the Crayfish, Astacus trowbridgii Stimpson. Annot Zool Jpn. 1962.

- Crandall K, De Grave S. An updated classification of the freshwater crayfishes (Decapoda: Astacidea) of the world, with a complete species list. J Crustac Biol. 2017;37.

- Gregory, TR. CHAPTER 1 - Genome Size Evolution in Animals. In: Gregory TR, editor. The Evolution of the Genome. Burlington: Academic Press; 2005. p. 3–87.

- Tørresen OK, Star B, Mier P, Andrade-Navarro MA, Bateman A, Jarnot P, et al. Tandem repeats lead to sequence assembly errors and impose multi-level challenges for genome and protein databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:10994–1006. [CrossRef]

- Treangen TJ, Salzberg SL. Repetitive DNA and next-generation sequencing: computational challenges and solutions. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:36–46. [CrossRef]

- Pop, M. Genome assembly reborn: recent computational challenges. Brief Bioinform. 2009;10:354–66. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro JA, Sternberg R von. Why repetitive DNA is essential to genome function. Biol Rev. 2005;80:227–50.

- Jurka J, Kapitonov VV, Kohany O, Jurka MV. Repetitive Sequences in Complex Genomes: Structure and Evolution. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2007;8:241–59.

- Garrido-Ramos, MA. Satellite DNA: An Evolving Topic. Genes. 2017;8:230. [CrossRef]

- Macas J, Neumann P, Navrátilová A. Repetitive DNA in the pea (Pisum sativum L.) genome: comprehensive characterization using 454 sequencing and comparison to soybean and Medicago truncatula. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:427. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ruano FJ, López-León MD, Cabrero J, Camacho JPM. High-throughput analysis of the satellitome illuminates satellite DNA evolution. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28333. [CrossRef]

- Mravinac B, Plohl M, Ugarković Ð. Preservation and High Sequence Conservation of Satellite DNAs Suggest Functional Constraints. J Mol Evol. 2005;61:542–50. [CrossRef]

- Miga, KH. Completing the human genome: the progress and challenge of satellite DNA assembly. Chromosome Res Int J Mol Supramol Evol Asp Chromosome Biol. 2015;23:421–6. [CrossRef]

- Plohl M, Luchetti A, Meštrović N, Mantovani B. Satellite DNAs between selfishness and functionality: Structure, genomics and evolution of tandem repeats in centromeric (hetero)chromatin. Gene. 2008;409:72–82. [CrossRef]

- Plohl M, Meštrović N, Mravinac B. Satellite DNA Evolution. Repetitive DNA. 2012;7:126–52. [CrossRef]

- Pezer Ž, Brajković J, Feliciello I, Ugarković Đ. Satellite DNA-Mediated Effects on Genome Regulation. In: Genome Dynamics. 2012. p. 153–69. [CrossRef]

- Biscotti MA, Canapa A, Forconi M, Olmo E, Barucca M. Transcription of tandemly repetitive DNA: functional roles. Chromosome Res. 2015;23:463–77. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, BIESIOT P, SKINNER D. Toward an Understanding of Satellite DNA Function in Crustacea. Integr Comp Biol. 1999;39. [CrossRef]

- Bourque G, Burns KH, Gehring M, Gorbunova V, Seluanov A, Hammell M, et al. Ten things you should know about transposable elements. Genome Biol. 2018;19:199. [CrossRef]

- Bennetzen JL, Wang H. The Contributions of Transposable Elements to the Structure, Function, and Evolution of Plant Genomes. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2014;65:505–30. [CrossRef]

- Deininger PL, Moran JV, Batzer MA, Kazazian HH. Mobile elements and mammalian genome evolution. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:651–8. [CrossRef]

- Craig NL, Lambowitz A, Gragie R, Gellert M. Mobile DNA II. ASM Press; 2002.

- Kim Y-J, Lee J, Han K. Transposable Elements: No More “Junk DNA.” Genomics Inform. 2012;10:226–33. [CrossRef]

- Barrón MG, Fiston-Lavier A-S, Petrov DA, González J. Population Genomics of Transposable Elements in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet. 2014;48:561–81. [CrossRef]

- Burns KH, Boeke JD. Human Transposon Tectonics. Cell. 2012;149:740–52. [CrossRef]

- Lanciano S, Mirouze M. Transposable elements: all mobile, all different, some stress responsive, some adaptive? Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2018;49:106–14. [CrossRef]

- Slotkin RK, Martienssen R. Transposable elements and the epigenetic regulation of the genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:272–85. [CrossRef]

- Wicker T, Sabot F, Hua-Van A, Bennetzen JL, Capy P, Chalhoub B, et al. A unified classification system for eukaryotic transposable elements. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:973–82. [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, L. All Quiet on the TE Front? The Role of Chromatin in Transposable Element Silencing. Cells. 2022;11:2501. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, KK. Structural and sequence diversity of eukaryotic transposable elements. Genes Genet Syst. 2019;94:233–52. [CrossRef]

- Flynn JM, Hubley R, Goubert C, Rosen J, Clark AG, Feschotte C, et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117:9451–7. [CrossRef]

- Smit, AFA, Hubley, R & Green, P. RepeatMasker Open-4.0. http://www.repeatmasker.org. 2013-2015.

- Bao Z, Eddy SR. Automated De Novo Identification of Repeat Sequence Families in Sequenced Genomes. Genome Res. 2002;12:1269–76. [CrossRef]

- Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21 suppl_1:i351–8. [CrossRef]

- Ou S, Jiang N. LTR_retriever: A Highly Accurate and Sensitive Program for Identification of Long Terminal Repeat Retrotransposons1[OPEN]. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:1410–22. [CrossRef]

- Flutre T, Duprat E, Feuillet C, Quesneville H. Considering Transposable Element Diversification in De Novo Annotation Approaches. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16526. [CrossRef]

- Novák P, Neumann P, Pech J, Steinhaisl J, Macas J. RepeatExplorer: a Galaxy-based web server for genome-wide characterization of eukaryotic repetitive elements from next-generation sequence reads. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:792–3. [CrossRef]

- Chikhi R, Medvedev P. Informed and automated k-mer size selection for genome assembly. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:31–7. [CrossRef]

- Novák P, Ávila Robledillo L, Koblížková A, Vrbová I, Neumann P, Macas J. TAREAN: a computational tool for identification and characterization of satellite DNA from unassembled short reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:e111. [CrossRef]

- Bao W, Kojima KK, Kohany O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mob DNA. 2015;6:11. [CrossRef]

- Demsˇar J, Curk T, Erjavec A, Demsar J, Curk T, Erjave A, et al. Orange: Data Mining Toolbox in Python. :5.

- Silva BSML, Picorelli ACR, Kuhn GCS. In Silico Identification and Characterization of Satellite DNAs in 23 Drosophila Species from the Montium Group. Genes. 2023;14:300. [CrossRef]

- Pita S, Panzera F, Mora P, Vela J, Cuadrado Á, Sánchez A, et al. Comparative repeatome analysis on Triatoma infestans Andean and Non-Andean lineages, main vector of Chagas disease. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:e0181635. [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Gimenez OM, Koelman J, Palmada-Flores M, Bradford TM, Jones KK, Cooper SJB, et al. Comparative analysis of morabine grasshopper genomes reveals highly abundant transposable elements and rapidly proliferating satellite DNA repeats. BMC Biol. 2020;18:199. [CrossRef]

- Utsunomia R, Silva DMZ de A, Ruiz-Ruano FJ, Goes CAG, Melo S, Ramos LP, et al. Satellitome landscape analysis of Megaleporinus macrocephalus (Teleostei, Anostomidae) reveals intense accumulation of satellite sequences on the heteromorphic sex chromosome. Sci Rep. 2019;9:5856. [CrossRef]

- Sproul JS, Hotaling S, Heckenhauer J, Powell A, Larracuente AM, Kelley JL, et al. Repetitive elements in the era of biodiversity genomics: insights from 600+ insect genomes. preprint. Genomics; 2022.

- Logsdon GA, Vollger MR, Eichler EE. Long-read human genome sequencing and its applications. Nat Rev Genet. 2020;21:597–614. [CrossRef]

- Paajanen P, Kettleborough G, López-Girona E, Giolai M, Heavens D, Baker D, et al. A critical comparison of technologies for a plant genome sequencing project. GigaScience. 2019;8:giy163. [CrossRef]

- Kawato S, Nishitsuji K, Arimoto A, Hisata K, Kawamitsu M, Nozaki R, et al. Genome and transcriptome assemblies of the kuruma shrimp, Marsupenaeus japonicus. G3 GenesGenomesGenetics. 2021;11:jkab268. [CrossRef]

- Jin S, Bian C, Jiang S, Han K, Xiong Y, Zhang W, et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of the oriental river prawn, Macrobrachium nipponense. GigaScience. 2021;10:giaa160. [CrossRef]

- Veldsman WP, Ma KY, Hui JHL, Chan TF, Baeza JA, Qin J, et al. Comparative genomics of the coconut crab and other decapod crustaceans: exploring the molecular basis of terrestrial adaptation. BMC Genomics. 2021;22:1–15. [CrossRef]

- Gutekunst J, Andriantsoa R, Falckenhayn C, Hanna K, Stein W, Rasamy J, et al. Clonal genome evolution and rapid invasive spread of the marbled crayfish. Nat Ecol Evol. 2018;2:567–73. [CrossRef]

- Austin CM, Croft LJ, Grandjean F, Gan HM. The NGS Magic Pudding: A Nanopore-Led Long-Read Genome Assembly for the Commercial Australian Freshwater Crayfish, Cherax destructor. Front Genet. 2022;12. [CrossRef]

- Tan MH, Gan HM, Lee YP, Grandjean F, Croft LJ, Austin CM. A Giant Genome for a Giant Crayfish (Cherax quadricarinatus) With Insights Into cox1 Pseudogenes in Decapod Genomes. Front Genet. 2020;11. [CrossRef]

- Polinski JM, Zimin AV, Clark KF, Kohn AB, Sadowski N, Timp W, et al. The American lobster genome reveals insights on longevity, neural, and immune adaptations. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabe8290. [CrossRef]

- Xu Z, Gao T, Xu Y, Li X, Li J, Lin H, et al. A chromosome-level reference genome of red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii provides insights into the gene families regarding growth or development in crustaceans. Genomics. 2021;113:3274–84. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Ren X, Liu P, Li J, Lv J, Wang J, et al. High-quality genome assembly of Chinese shrimp (Fenneropenaeus chinensis) suggests genome contraction and adaptation to the environment. preprint. Preprints; 2021.

- Katneni VK, Shekhar MS, Jangam AK, Krishnan K, Prabhudas SK, Kaikkolante N, et al. A Superior Contiguous Whole Genome Assembly for Shrimp (Penaeus indicus). Front Mar Sci. 2022;8. [CrossRef]

- Uengwetwanit T, Pootakham W, Nookaew I, Sonthirod C, Angthong P, Sittikankaew K, et al. A chromosome-level assembly of the black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) genome facilitates the identification of growth-associated genes. Mol Ecol Resour. 2021;21:1620–40. [CrossRef]

- Yuan J, Zhang X, Li F, Xiang J. Genome Sequencing and Assembly Strategies and a Comparative Analysis of the Genomic Characteristics in Penaeid Shrimp Species. Front Genet. 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Yuan J, Sun Y, Li S, Gao Y, Yu Y, et al. Penaeid shrimp genome provides insights into benthic adaptation and frequent molting. Nat Commun. 2019;10:356. [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Ge S, Bhandari S, Fan C, Jiao Y, Gai C, et al. Genome characterization and comparative analysis among three swimming crab species. Front Mar Sci. 2022;9. [CrossRef]

- Tang B, Zhang D, Li H, Jiang S, Zhang H, Xuan F, et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly reveals the unique genome evolution of the swimming crab (Portunus trituberculatus). GigaScience. 2020;9:giz161. [CrossRef]

- Bachvaroff TR, McDonald RC, Plough LV, Chung JS. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus. G3 GenesGenomesGenetics. 2021;11:jkab212. [CrossRef]

- Tang B, Wang Z, Liu Q, Wang Z, Ren Y, Guo H, et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Paralithodes platypus provides insights into evolution and adaptation of king crabs. Mol Ecol Resour. 2021;21:511–25. [CrossRef]

- Tang B, Wang Z, Liu Q, Zhang H, Jiang S, Li X, et al. High-Quality Genome Assembly of Eriocheir japonica sinensis Reveals Its Unique Genome Evolution. Front Genet. 2020;10. [CrossRef]

- Petersen M, Armisén D, Gibbs RA, Hering L, Khila A, Mayer G, et al. Diversity and evolution of the transposable element repertoire in arthropods with particular reference to insects. BMC Ecol Evol. 2019;19:11. [CrossRef]

- Wu C, Lu J. Diversification of Transposable Elements in Arthropods and Its Impact on Genome Evolution. Genes. 2019;10:338. [CrossRef]

- Shao C, Sun S, Liu K, Wang J, Li S, Liu Q, et al. The enormous repetitive Antarctic krill genome reveals environmental adaptations and population insights. Cell. 2023;186:1279-1294.e19. [CrossRef]

- Lyon, MF. Do LINEs have a role in X-chromosome inactivation? J Biomed Biotechnol. 2006;2006:59746.

- Dodsworth S, Chase MW, Kelly LJ, Leitch IJ, Macas J, Novák P, et al. Genomic Repeat Abundances Contain Phylogenetic Signal. Syst Biol. 2015;64:112–26. [CrossRef]

- Dodsworth S, Jang T-S, Struebig M, Chase MW, Weiss-Schneeweiss H, Leitch AR. Genome-wide repeat dynamics reflect phylogenetic distance in closely related allotetraploid Nicotiana (Solanaceae). Plant Syst Evol. 2017;303:1013–20. [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, Swergold GD, Seldin MF. Examination of sequence homology between human chromosome 20 and the mouse genome: intense conservation of many genomic elements. Hum Genet. 2003;113:60–70. [CrossRef]

- Silva JC, Shabalina SA, Harris DG, Spouge JL, Kondrashovi AS. Conserved fragments of transposable elements in intergenic regions: evidence for widespread recruitment of MIR- and L2-derived sequences within the mouse and human genomes. Genet Res. 2003;82:1–18. [CrossRef]

- Vitales D, Garcia S, Dodsworth S. Reconstructing phylogenetic relationships based on repeat sequence similarities. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2020;147:106766. [CrossRef]

- Bao W, Tang KFJ, Alcivar-Warren A. The Complete Genome of an Endogenous Nimavirus (Nimav-1_LVa) From the Pacific Whiteleg Shrimp Penaeus (Litopenaeus) Vannamei. Genes. 2020;11:94. [CrossRef]

- Sotero-Caio CG, Platt RN II, Suh A, Ray DA. Evolution and Diversity of Transposable Elements in Vertebrate Genomes. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9:161–77. [CrossRef]

| Suborder/ infraorder | Species | Ab Initio satDNA Families Identified | Number of Families Annotated Using RMo Species Specific and Repbase as Library for Each Species | Number of Families Annotated Using Merged Libraries of RMo and Tp Libraries for All Species and Repbase | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMo | Tp | All RE Families | Percentage of Unknown | Satdna Only | All RE Families | Percentage of Unknown | satDNA Only | ||

| Dendrobranchiata | Penaeus chinensis | 1 | 7 | 7547 | 12.38% | 24 | 22702 | 3.44% | 56 |

| Penaeus indicus | 1 | 2 | 8252 | 7.72% | 30 | 24237 | 3.40% | 57 | |

| Penaeus japonicus | 3 | 5 | 7693 | 7.25% | 29 | 22611 | 3.61% | 59 | |

| Penaeus monodon | 0 | 4 | 8647 | 9.28% | 28 | 25183 | 3.57% | 57 | |

| Penaeus vannamei | 0 | 3 | 7621 | 8.85% | 30 | 23240 | 3.49% | 55 | |

| Caridea | Caridina multidentata | 1 | 6 | 11104 | 11.93% | 38 | 28065 | 11% | 74 |

| Macrobrachium nipponense | 2 | 0 | 10455 | 19.68% | 38 | 26021 | 13.42% | 57 | |

| Achelata | Panulirus ornatus | 1 | 6 | 8850 | 21.13% | 35 | 25995 | 8.12% | 60 |

| Astacidea | Procambarus virginalis | 1 | 31 | 9213 | 28.26% | 33 | 26483 | 9.95% | 96 |

| Procambarus clarkii | 2 | 39 | 8838 | 22.52% | 34 | 26051 | 13.67% | 97 | |

| Cherax destructor | 4 | 24 | 10391 | 14.10% | 40 | 29970 | 6.88% | 92 | |

| Cherax quadricarinatus | 1 | 43 | 10411 | 14.33% | 35 | 26966 | 4.99% | 96 | |

| Homarus americanus | 1 | 2 | 9557 | 24.16% | 35 | 27873 | 17.29% | 61 | |

| Anomura | Paralithodes camtschaticus | 2 | 19 | 11431 | 24.95% | 33 | 30169 | 14.36% | 95 |

| Paralithodes platypus | 0 | 36 | 11332 | 32.76% | 34 | 31798 | 13.27% | 109 | |

| Birgus latro | 1 | 2 | 11053 | 25.48% | 37 | 31207 | 16.30% | 59 | |

| Brachyura | Chionoecetes opilio | 0 | 0 | 10400 | 22.89% | 29 | 26561 | 12.26% | 52 |

| Eriocheir sinensis | 1 | 0 | 8486 | 20.74% | 29 | 23937 | 11.82% | 49 | |

| Portunus trituberculatus | 0 | 0 | 7399 | 12.28% | 20 | 21070 | 6.42% | 39 | |

| Callinectes sapidus | 0 | 2 | 6911 | 13.68% | 188 | 19041 | 8.68% | 31 | |

| Other crustaceans | Amphibalanus Amphitrite (Cirripedia) | 1 | 1 | 6717 | 27.06% | 14 | 11969 | 14.90% | 22 |

| Armadillidium vulgare (Isopoda) | 0 | 13 | 9431 | 17.40% | 27 | 19098 | 11.91% | 47 | |

| Daphnia magna(Phyllopoda) | 2 | 3 | 3643 | 17.90% | 10 | 6805 | 14.63% | 11 | |

| Darwinula stevensoni (Podocopida) | 1 | 2 | 9762 | 25.59% | 22 | 17339 | 23.89% | 38 | |

| Eurytemora affinis(Copepoda) | 1 | 8 | 6069 | 33.37% | 32 | 13334 | 24.15% | 46 | |

| Hyalella Azteca(Amphipoda) | 1 | 10 | 6851 | 16.21% | 28 | 14424 | 13.69% | 46 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).