1. Introduction

The overall objective of this project was to develop and implement a collaboration model for general practitioners (GP) and hospital cardiologists that allows evaluation of frail elderly patients to timely diagnose atrial fibrillation (AF) at less of a burden for the patient.

The prevalence of AF in Denmark is 0.4–1.0% [

1], increasing with age [

1,

2] and causing important morbidity, especially in the elderly [

3]. Palpitations, dizziness, and fatigue are symptoms of AF, but approximately 30% have no symptoms [

4,

5,

6]. Patients with little or no symptoms of AF pose a diagnostic challenge, especially among frail elderly patients, as they have a particularly high risk of stroke [

7,

8], which can be prevented with timely anticoagulant medication [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The decision to use oral anticoagulation must be balanced with the concomitant risk of bleeding [

14,

21].

In the conventional diagnostic workup on patients suspected to have AF paroxysms, the GP refers the patients to the hospital cardiologists for evaluation, including heart rhythm monitoring. Patients are requested to meet at the outpatients clinic several times before the diagnosis is confirmed or rejected and treatment might be initiated. This is cumbersome, especially for patients who are physically or mentally frail, who often need help for transportation. These patients tend not be referred or terminate the diagnostic workup prematurely, still suffering the risk of subsequent stroke due to possible non-diagnosed AF. The REAFEL-study (REAching the Frail ELderly) was designed to simplify the workup process for diagnosis and management of AF, reducing the physical meetings at the hospital. In REAFEL, GPs can use a simple continuous cardiac rhythm monitoring (Holter) device, receive support from cardiologists to interpret the results and to guide decisions on need for referral to the cardiologist and choice of adequate anticoagulation therapy. In this assessment, the dialogue between the cardiologist and the GP can be of crucial importance in making the correct decision, as the GP often knows the patient’s risk of bleeding and preferences of treatment. Additionally, in REAFEL patients could have video consultations with the cardiologist in cooperation with their GP.

2. Materials and Methods

After an initial phase to develop the CardioShare model for AF diagnosis and management, the model was evaluated with a cluster-randomization. Subsequently, the implementation potential was evaluated in an escalation test. The Danish company Cortrium ApS (Copenhagen, Denmark) provided C3+ sensors which are compact three-channel (Holter) sensors that can be connected to conventional electrodes and are easy to manage without special skills.

The trial is registered in

www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04162548) and meets the criteria for a Pragmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary (PRECIS) as follows [

22,

23]:

(1) Patients evaluated in the project are the same as those evaluated in conventional practice. (2) Patient inclusion happens in connection with an ordinary consultation. (3) The healthcare staff treating the patients in the project (GPs, and cardiologists) are the same as those treating patients routinely. (4) The resources used in the project (GPs, cardiologists, and nurses at the outpatient department, who evaluated the Holter monitor recordings) are the same as those conducting evaluations in the conventional process at the outpatient department. (5) The proposed CardioShare model is intended to be as flexible as the conventional outpatient diagnostic evaluation. (6) Follow-up of patients is the same as for conventional evaluation, except that study patients were asked to participate in study specific interviews. (7) The primary outcome is clinically relevant for the usual patient-evaluation process. In this project primary outcome is the time spent from deciding to monitor the heart rhythm until adequate treatment is initiated based on conclusive diagnosis. (8) All the data collected in the project have been analyzed as part of the primary outcome.

The cluster-randomization study was conducted from February 2020 to December 2021. Nine GP clinics were gradually included as clusters and randomized 1:1 to use a C3+ sensor for heart rhythm monitoring and deciding whether to refer the patient to the cardiologist (control group) or to use C3+ sensor for managing the patient guided remotely by a cardiologist, i.e. using the CardioShare model (intervention group). Inclusion of the clinics was based on outreach meetings and networking. Each clinic was randomized as a cluster and managed all patients from the clinic according to the allocated randomization. All Holter reports were evaluated and approved by the hospital’s cardiologists, who could review recordings on demand.

Observation parameters recorded were: (1) CardioShare: number of days from GP’s first message to a cardiologist to results and recommendations sent to GP by a cardiologist, (2) non-CardioShare: number of days from initiation of recording to results and recommendations sent to GP by a cardiologist. To standardize our statistics, all delayed cases as well as those with more than one Holter recording have not been considered. Our results were compared to a cohort of patients (n=117) who attended the outpatient department at Bispebjerg-Frederiksberg Hospital throughout January 2019 for initiation of Holter monitoring as reference for usual care, measuring: the number of days from date of referral to results and recommendations given to patient and/or sent to the patient’s GP (whichever was earliest).

Inclusion criteria. We encouraged GPs to include patients they considered frail elderly but inclusion was liberal to explore other patient groups relevant from a primary care perspective.

To define “frailty” we used a modified version of the simple criteria described for the age group at the greatest risk of stroke from AF (

Table 1) [

25,

26,

27]. The basic indications for referral were classified according to

Table 2.

Exclusion criteria. Patients younger than 18 years, and patients who did not provide written informed consent were excluded from the project. Likewise, patients with suspicion of severe arrhythmia who needed to be referred to a cardiologist and who could attend the outpatient department were excluded.

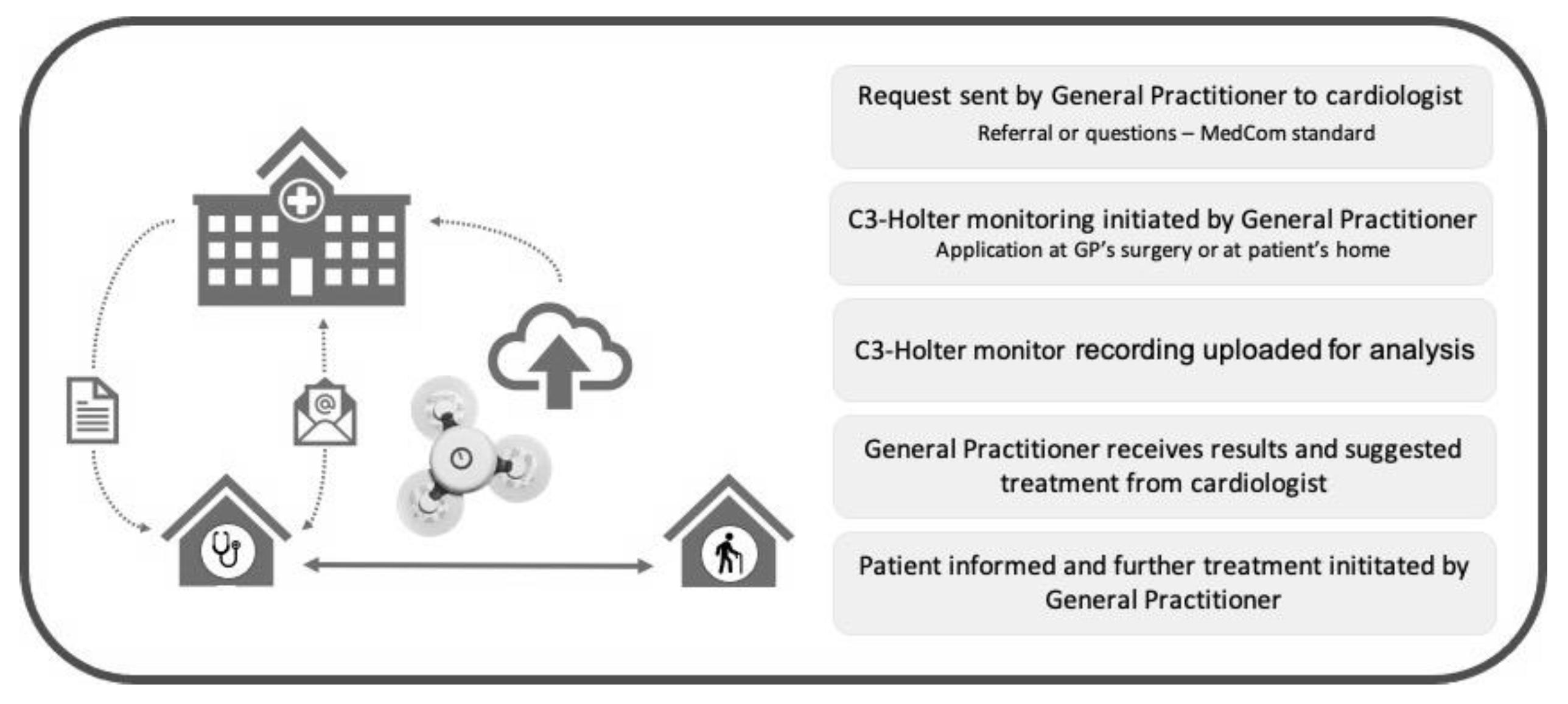

2.1. The CardioShare Model

To receive remote support by cardiologists, GPs used the national platform for cross-sector communication MedCom (

www.medcom.dk/standarder). The cardiologist confirmed the indication for monitoring or asked for further information before the GP initiated Holter monitoring. Length of monitoring varied from one to seven days, according to the cardiologist’s advice. Subsequently, all recordings were uploaded to a cloud-based analysis platform provided by Cortrium. The cardiologist received a notification from Cortrium when recordings had been analyzed and a report was available, then forwarded the report to the GP along with advice on how to manage the patient according to the findings. The GP informed the patients if further evaluation or treatment at the cardiology department was recommended. With patient consent, the GP would then send a message to the cardiologist, who could schedule an appointments with the patient without additional referral. The GP could ask the cardiologist to communicate directly with the patient by means of video or phone consultation.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the process.

The procedure for monitoring was the same for GPs in the control group, but they initiated monitoring as they deemed indicated, and solely decided patient management, including whether to refer the patient to a cardiologist for further evaluation. In the control group, the monitoring reports from the cloud-based analysis platform were sent to the GPs without advice on patient management.

2.2. Patient Reported Experiences

To explore participation patients’ experiences of the diagnostic process, all patients who completed a Holter monitor recording have been contacted by phone and asked to answer a short survey. When patients did not complete the survey, we recorded the reason as: no contact data available in the patient’s electronic journal, the patient did not answer the phone after at least three attempts, the patient did not want to participate, the patient did not understand the survey’s questions due language issues or impaired cognitive function.

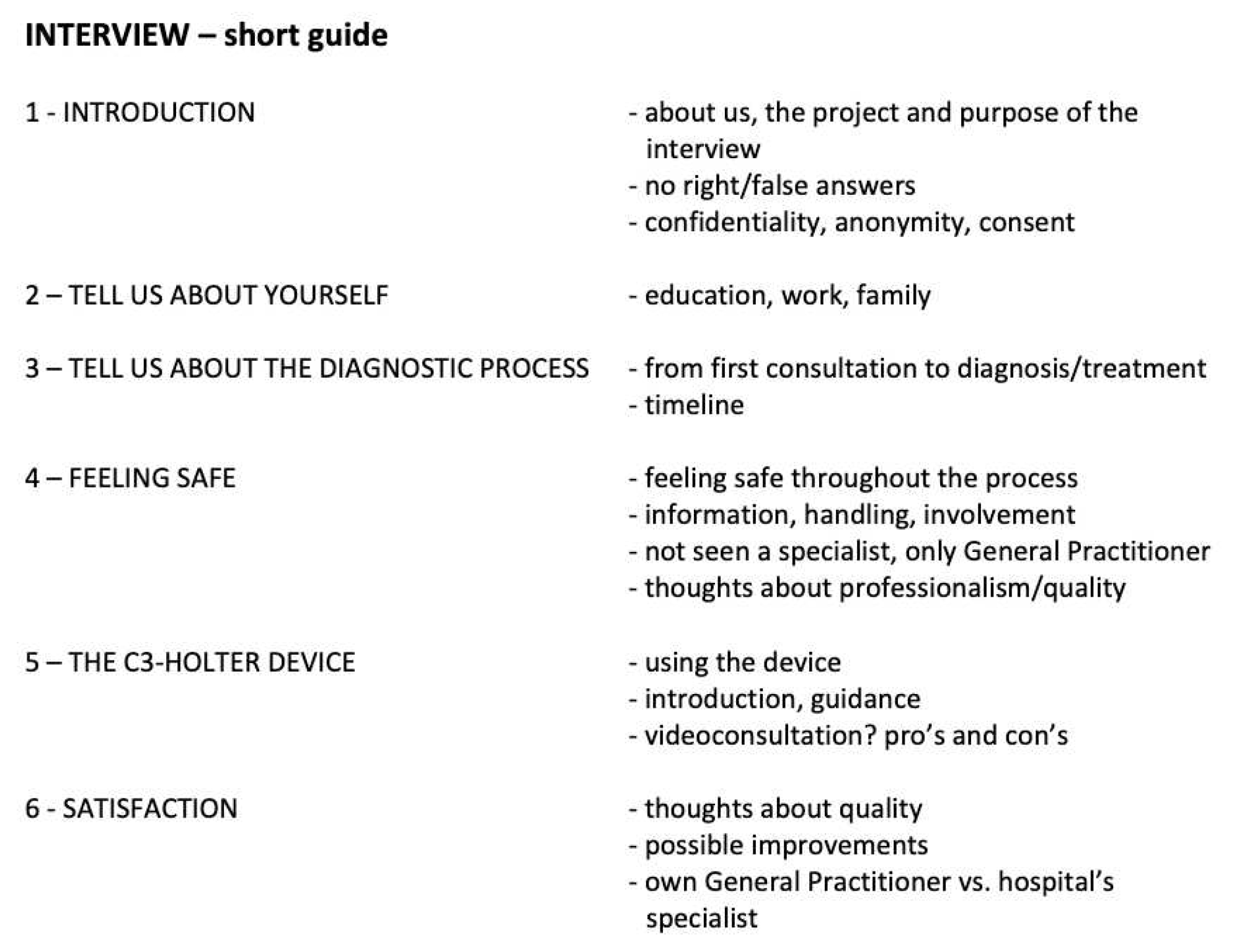

To further explore the data collected through the survey, we randomly selected 20% of the patients among those who completed it and invited them to participate in a semi-structured interview concerning their experiences during the diagnostic process. To minimize the biased selection of participants in these interviews every 5

th patient was invited. If the invitation was not successful, the next patient on the list was invited. The semi-structured interviews were conducted according to a guide that included a list of the topics that we wanted to explore during the interview (

Figure A1). Throughout every conversation the interviewers encouraged the respondents to speak freely and only asked questions to elaborate within the topics of interest. The conversations were recorded and evaluated continuously, until sufficient data had been collected, i.e. data saturation, when interviews of two consecutive patients did not provide any new aspects within the fields of topics. Interview recordings were subsequently transcribed verbatim. Two researchers independently coded all interviews before analyzing the patients’ narrations and organized the large amount of text in a concise summary of key results, as described by Erlingsson and Brysiewicz [

28].

2.3. Participating Health Care Professionals’ Experiences

In addition to patient interviews, we also invited GPs and nurses to participate in interviews to explore their experiences with the CardioShare model. We conducted 14 interviews with in total eight GPs and six nurses from both clusters. All conversations were recorded and analyzed using the same method as described for patient interviews.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Randomized Study

3.1.1. CardioShare Versus Non-CardioShare

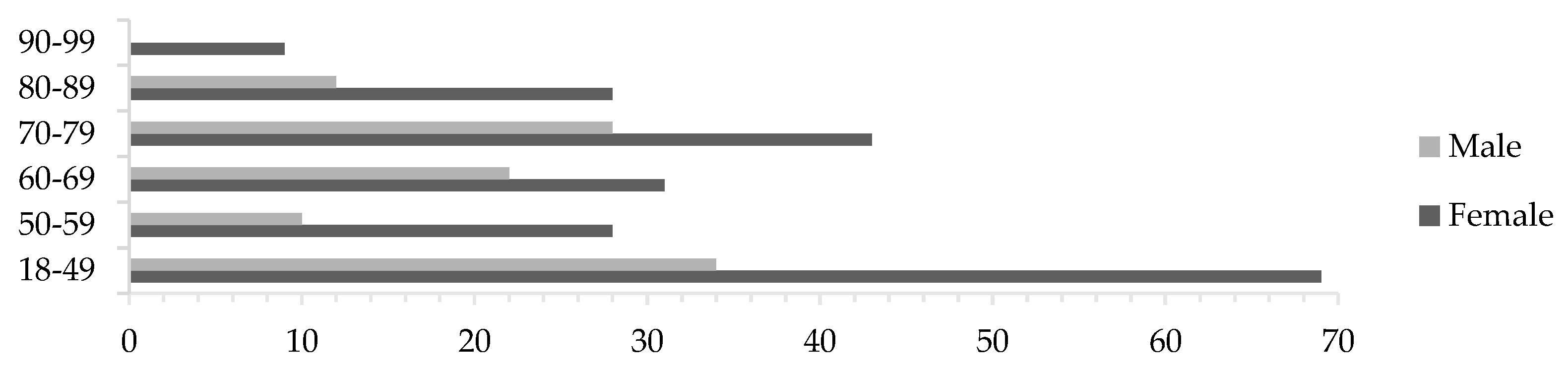

From February 2020 to December 2021 a total of 314 patient cases were evaluated; 122 were randomized CardioShare and 111 to non-CardioShare. The remaining 81 cases have been enrolled by GPs at our feasibility phase clinic resulting in a non-randomized mixture of Cardio Share and non-CardioShare patients. Predominantly female patients participated in the study, across all ages (

Figure 2), with a median age of all participants of 62,5 years. In total, 85 patients (27%) were classified “frail”; 61 female and 24 male. In 12 cases Holter-recording was repeated and one patient underwent a third recording. User failures occurred in eight cases, mostly due to a lack of routine among the staff in the start-up phase of the project. In four cases the cardiologists recommended a follow-up recording based on the patient’s symptoms. The patient who underwent a third recording did so due to new symptoms six months after the initial recordings.

There were recorded delays in the workout process in 64 cases; six caused by the patient, 33 caused by the GP, and 25 by the cardiologist.

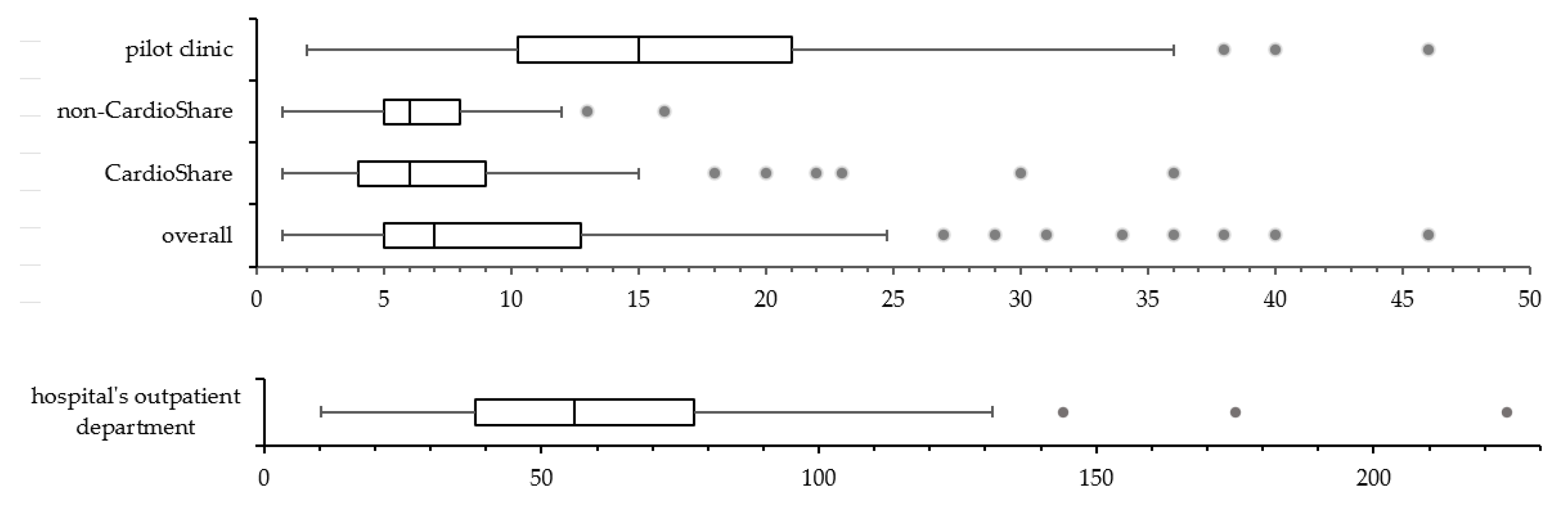

For one month (January 2019), a total of 117 patients were referred to the hospital’s outpatient department to undergo Holter recording. The duration of the diagnostic process was measured from the date of referral to the date when the cardiologist gave the results to either the patient’s GP or the patient themselves. The mean duration of the diagnostic process for AF was 63 days, ranging from 10 to 224 days, and 75% of all patients have been diagnosed within 78 days (

Figure 3, bottom). In comparison, in the REAFEL study the mean duration of the workout for diagnosing AF was shorter (from 1 to 25 days) for all patients, as 75% of all patients had AF diagnosed/not found within 13 days (

Figure 3, top).

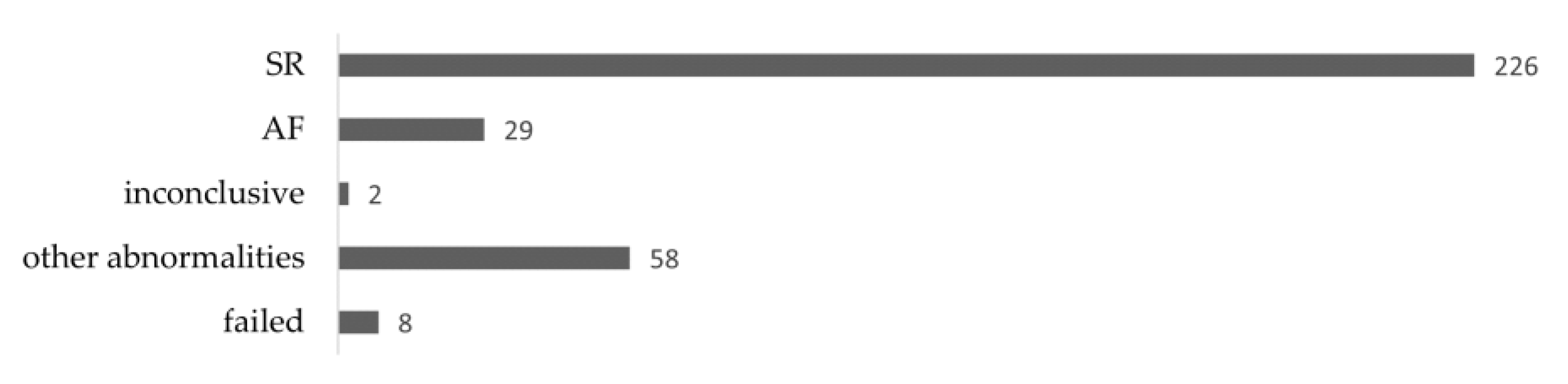

Among a total of 323 C3+ recordings, 29 patients (9.0%) were diagnosed with AF. The majority, 226 recordings (70.0%), showed normal sinus rhythm, whilst 58 (18.0%) showed other abnormalities, two were inconclusive, and eight recordings failed. In 257 cases (79.6%), no further involvement of the cardiologist was needed, and the GP took over further treatment if necessary/as advised. 46 recordings (14.2%) resulted in the patient’s referral to a cardiologist for further diagnostics. In 16 cases (5.0%) cardiologists advised to perform another Holter recording – 8 of those due to failed recording (

Figure 4).

conduct Of the 58 recordings that showed other abnormalities than AF, 33 (56.9%) resulted in referral to a cardiologist for further diagnostics, whilst 21 cases (36.2%) could be handled by the GP without further involvement of other specialists. In three cases, the cardiologists advised to another recording, and in one case the protocol was violated (non-CardioShare cluster) as the patient’s GP was advised to change medication.

3.1.2. Escalation Test

After the cluster-randomized study had ended (December 2021) a workshop was held where more GPs and cardiologists from other hospitals in the Capital Region of Denmark were invited to discuss the experiences and how CardioShare could be implemented for diagnosis and management of AF. There was a consensus that GPs could initiate Holter monitoring and interpret the results provided that the cardiologist continued to respond within short time to the requests from GPs with doubts on indication for Holter monitoring, on the results of the report or the following evaluation and/or treatment of the patients. Four cardiology sites with hospital cardiologists and two private practicing cardiologists used the CardioShare model to support 58 GPs distributed in 13 clinics in the escalation test, from February to April 2022. In total 93 patients were evaluated at their GP’s using C3+ and supported through the CardioShare model. The Cardiology Council approved this procedure as an additional standard of care method in the Capital Region of Denmark.

3.2. Survey

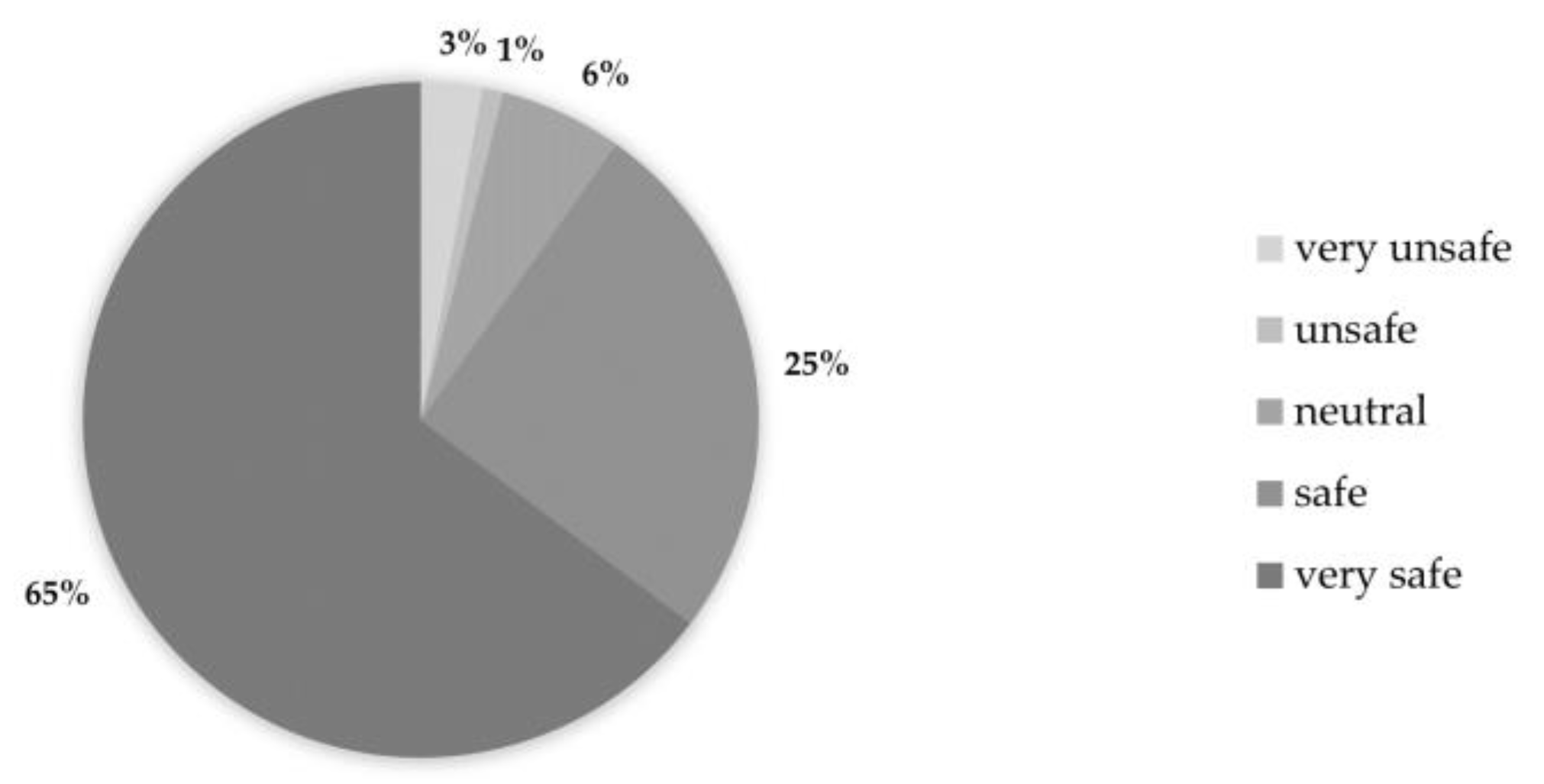

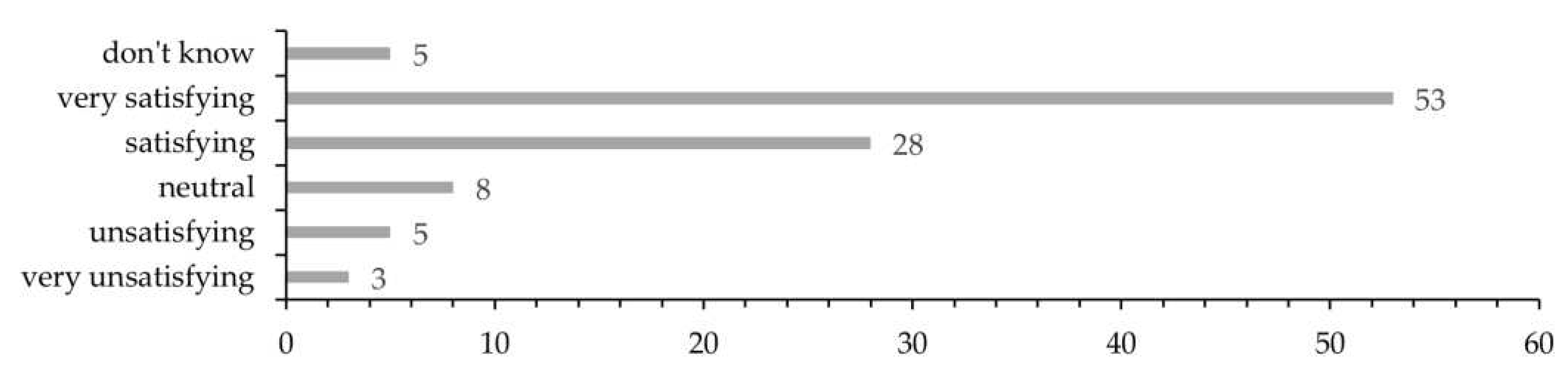

In total, 160 patients were asked to participate in the survey, of whom 102 (63.8%) accepted. The patients were asked how safe they felt from the time they saw their GP due to their symptoms until being explained the outcome of Holter recording. In total 90.2% of the patients felt either safe (25.5%) or very safe (64.7%), while 3.9% of the patients felt unsafe or very unsafe (

Figure 5). A total of 81 patients (79.4%) were either satisfied (27.5%) or very satisfied (52.0%) with the organization of the diagnostic process. A few didn’t answer this question (4.9%), and 7.8% of the patients were unsatisfied (4.9%) or very unsatisfied (2.9%) (

Figure 6). We were aware that patients tend to answer less critical when responding the survey’s closed questions regarding overall satisfaction with the workout process. Therefore, we addressed this specifically as open-question during the interviews.

The C3+ sensor was evaluated user-friendly by 84.3% of the patients, whilst 4.9% had bad or very bad experiences with it. There is no association for this point with their level of satisfaction with the overall process. Hence, we can assume that the reasons for patients not being satisfied with the diagnostic evaluation process may be related to the doctor-patient relationship or to organizational matters.

When asked how worried the patients were about the symptoms for which they requested help from their GP, in total 38 patients (37.3%) were either worried or very worried at that time. This number was halved at the end of the diagnostic process (15.7% were worried or very worried), while 25 patients (24.5%) stated the same level of concern before and after diagnostic evaluation. In depth analysis showed that 8 of these 25 patients answered “not worried at all” in both cases, whilst other five patients (4.9%) answered “worried”, and three (2.9%) “very worried” to both questions. Five patients (4.9%) indicated a higher level of concern after the diagnostic process was fulfilled.

3.3. Semi-Structured Interviews with Patients

In total, 11 interviews have been conducted until sufficient data was collected. Through analysis of the patients’ narratives (

Table B1), three main themes (i.e. hypotheses to be confirmed or disproved) could be identified: (1) Patients experience a high level of professionalism and quality despite not being seen by a cardiologist; (2) The C3-holter device is user friendly and easy to handle; and (3) Being diagnosed by their own GP makes patients feel safe and secure. In this section we will present the main results within these themes.

3.3.1. Patients Expericence a High Level of Professionalism and Quality Despite Not Being Seen by a Cardiologist

For most of the patients it does not make any difference that they only have been seen by their own GP. They are used to see their GP before being referred to a specialist, and they trust the diagnostic quality not being different whether they see a cardiologist or not. The patients are well informed that their GP and hospital’s cardiologists work together during the diagnostic process, and they are aware of the cardiologists’ role and responsibility:

”I assume there is no big difference between the approaches. It’s just the consultation that’s different. I wasn’t nervous at all about quality.”

”I was told that cardiologists saw my recording. So, it actually was the specialists who did analyze it.”

”I think it is just fine that cardiologists give advice [on further treatment] to my GP.”

One of the patients would have preferred to be seen by a cardiologist right away. After their Holter recording was analyzed, they didn’t get feedback from their GP before they called them to ask for it. Several other patients mention that it is important for them to be referred to a specialist right away if their symptoms could likely be caused by a severe condition. They do trust their GP in making the right decision whether they should be referred to a specialist right away:

”It depends on the severeness. If I’m having heart pain or feeling that my heart skips beats, I’d prefer to be referred to cardiologists right away. I’m sure my doctor would do so.”

3.3.2. The C3-holter Device Is User Friendly and Easy to Handle.

The device being very small, most patients forgot about it while wearing it. They had no problem wearing their clothes, and they didn’t change their everyday activities. The vast majority of them didn’t take the device off at all, not even to take a shower. The few patients who did take off the device didn’t experience problems afterwards when attaching it back to their chest. One patient told us that they didn’t try to detach and reattach it but were confident in being able to do so if necessary.

“I did the usual things - went for a walk every day, played some golf.”

“It was only three days, so I let it be and just washed around it.”

“They explained how to replace the patches, and I am comfortable to do so.”

“After a shower, I took it back on without any problem.”

The most common problem reported by the patients was discomfort caused by itchy skin reactions to the standard electrodes. They describe skin rush and more or less intense itching.

“I didn’t pay any attention to the device before my skin became itchy.”

“When you’ve been wearing it for three days, your skin has become very itchy, and you look forward to get rid of the device.”

A flashing light indicates whether the device is working properly. Some of the patients have been told this, others just reacted instinctively to any changes. In most cases the patients guessed bad connectivity to the skin to be the reason for the malfunction and tried to attach the device better. This didn’t always solve the problem though. Two patients told us that despite their efforts they couldn’t get the device attached good enough. In both cases inappropriate placement of the device on a female chest might have been the underlying cause. In one of these the poor placement even caused painful abrasions on the patient’s chest.

“The indicator was flashing, when the device was attached properly, but at some point, it had changed, and I thought it might have loosened. After I put it back on, the indicator flashed like before.”

“The patches weren’t attached very well. There was flashing green or white light depending on my movements.”

In one case the patient had to undergo two separate periods of monitoring, as the first recording was empty. During the second attempt the patient became aware of the flashing indicator light that was absent during the first recording. Most probably the cause was the device not having been turned on.

One function the patients emphasized is the possibility to set a marker on the recording. If the patient feels any kind of symptoms while wearing the Holter monitor, they just can push the device’s button and a time stamp is recorded for later review by the cardiologists.

“I quite liked the possibility to push the button when I was experiencing symptoms.”

“When I felt any kind of symptoms, there was this button I just could push to set a marker on the recording.”

3.3.3. Being Diagnosed by Their GP Makes the Patients Feel Safe and Secure

In every respect it is important that the patients trust the health professionals they are seeing. This also was expressed during our interviews. Most of the patients feel safe and secure with their GP but it depends on their interpersonal relationship - as mutual trust is build up over time.

”It depends on, which one of the GPs I’m seeing.”

”In the old days I felt safe, because you always saw the same doctor. They kind of knew your journal. Today there are many different [doctors/GPs].”

”I think it’s just fine, if it works. I think it’s nice, because it does mean a lot to feel comfortable with the person [doctor / health professional] you’re seeing.”

One factor that makes the patients feel safe and secure with their own GP is continuity - the health professional knows the patient’s medical (and even personal) history very well. The patients don’t need to tell everything from the very beginning, and they feel that their GP can consider their medical history as a whole.

”My doctor knows me and my medical history. A disease course can be broad, and specialists only look at things from their own discipline’s perspective.”

Some patients also mention that it is easier to conduct the monitoring at their GP’s surgery. They perceive it being time-saving and easier than attending the outpatient department at the hospital. They don’t have to wait for an appointment at the hospital to get the Holter recorder, and if necessary, monitoring can be started at the patient’s home - e.g. during the GP’s visit to a nursing home.

”There’s always a lot of waiting time. I prefer to see my GP.”

”I think it was nice, that the recording could be started right away.”

Especially for those who need help to get to the hospital, seeing their own GP seems to be a lot easier. One patient told us the following:

”When I need to go to the hospital I do need transportation help. I must be ready 90 minutes before, and then there’s waiting time and everything. I think it’s quite difficult.”

It is very important though, that the GP has taken the necessary steps to avoid communication problems or delays throughout the diagnostic process. The patients expect their GP to follow up on the analysis of their recordings and the results provided by the cardiologists. As one patient puts it: things must work out, appointments need to be kept and the process must be straightforward. The patients feel insecure if they don’t get any feedback or if there are technical problems.

”I hadn’t got any feedback from my GP. That was strange.”

”I called them after two weeks, because I hadn’t heard anything yet. I was told that the recording was empty.”

Except the few patients that reported technical or procedural problems during the diagnostic process, the patients in general were very comfortable with only seeing their GP and not being referred to the outpatient department at the hospital.

3.4. Semi-Structured Interviews with GP’s and Nurses

Through analysis of the health care professionals’ narratives, three main themes (i.e. hypotheses to be confirmed or disproved) could be identified: (1) The C3+ sensor is user friendly and easy to use in a GP’s setting; (2) Cooperation between GP and cardiologist is helpful and appreciated; and (3) Patients benefit from Holter monitoring at their GP’s. In this section we will present the main results within these themes.

3.4.1. The C3+ Sensor is User Friendly and Easy to Use in a GP’s Setting

Overall, the GPs were positive about using Holter monitoring as a diagnostic tool. They found the start-up process very smooth and experienced only a few technical problems. They were confident in using the device after the initial training, though a few nurses missed an easier quick guide than the one provided.

“I think it was quite straight forward. I just had to get used to how to send the correspondence [to the cardiologist] and what to write, but it was actually quite quick to get it sorted out.”

“There are so many sentences, with all sorts of things, and there are actually only four things you have to do, so you could actually […] make a much simpler guide.”

3.4.2. Cooperation between GP and Cardiologist is Helpful and Appreciated

In the beginning the participating GPs had to get used to communicating with the cardiologists instead of issuing a referral, but they have been very satisfied with the outcome of this communication.

“It has been, in other words, completely impeccable in every way.”

“When you have to interpret the results, it's extremely nice to have a cardiologist backing you up.”

Furthermore, the GPs valued the possibility of conducting Holter monitoring at their clinic without referral to a cardiologist.

’’Being able to do a Holter monitoring is like a function we have wanted, it has been difficult to access, […], and suddenly it has moved very close.”

“I think it belongs excellently here, at this level where you have professional cooperation along the way.”

3.4.3. Patients Benefit from Holter Monitoring at their GP’s

The health care personnel at the GPs’ clinics experienced a high level of satisfaction with the project among their patients, who felt safe and secure. And the GPs expressed their satisfaction with being able to conduct Holter monitoring with frail patients who otherwise wouldn’t be able to do so. They also found it beneficial to use the sensor on patients other than frail.

“We have a huge population, we have two nursing homes for which we are primary doctors.”

“We've actually used it primarily for the unconclusive [patient group], where we thought they're not quite candidates for a hospital cardiology evaluation process.”

“Health can be measured in many ways; whether they don't get blood clots, or whether they are reassured in their fear of illness.”

4. Discussion

The main result of this study is that the CardioShare model was feasible for diagnosis and management of AF. The process was shorter than usual care, it required fewer visits at the cardiology outpatient clinic, thus being less of a burden for the patients and reducing the capacity needed in the hospital’s outpatient department.

The aim of the study was to facilitate the management of frail elderly, and it is remarkable that two of the first 20 patients included by one of the GP’s needed a pacemaker. These patients were frail and had refused to be referred to the cardiology outpatient department for Holter monitoring, but accepted it to be performed by their GP, and to get implanted a pacemaker. Nevertheless, only 30% of all included patients fulfilled our frailty criteria (

Table 1). This is a weakness inherent in pragmatic implementation research while the liberal inclusion that was accepted in the study reflects the true need from GPs to evaluate other patients than those who are frail. From the cardiologists’ perspective, GPs were able to complete evaluation for arrhythmia suspicion of low-risk patients. Thus referral to the outpatient department was avoided, requiring fewer resources from the cardiology specialists. Nevertheless, no formal resource analysis was performed, which is a major limitation of this study.

Likewise, although patients reported a high level of satisfaction in the survey and following in-depth interviews, the study does not include standard quality-of-life questionnaires, which poses a limitation for comparisons with similar studies.

Although most patients were very satisfied with the diagnostic process being led by their GP, it cannot be concluded that the patients would have been less satisfied by being referred to the hospital’s outpatient department since this study did not include an analysis of patient reported experiences in a usual care group. Despite this limitation, it is remarkable that patients described the relationship with their GP as being crucial regarding whether they would prefer being referred to the hospital’s outpatient department. When implementing the CardioShare model it is important to ensure that the patients receive feedback on the results. Some patients did not receive any feedback, and were disappointed about it.

In general, the patients found the Holter device easy to use, e.g. not having any problems reattaching it to their chest after they took it off. Some patients experienced itching and chest discomfort while wearing the C3+ sensor. Since the C3+ device uses regular electrodes as those used in standard Holter devices, the general advice is to choose best tolerated electrodes. A folder with FAQ and troubleshooting guide for patients could be useful, and adequate training of all involved health care professionals is crucial as most problems with utilization of the Holter device seemed to be start-up difficulties that could be avoided.

From the GPs’ perspective, Holter monitoring with an easy-to-use compact device and support from hospital-based cardiologists was appreciated. They were very satisfied with the CardioShare cross-sectoral cooperation model, as they felt that their patients experienced an easy and safe approach throughout the workout process. They reported a great need for this kind of collaboration as they find it cumbersome to get access to Holter monitoring at the hospital’s outpatient department.

5. Conclusions

The CardioShare model is feasible with Holter monitoring performed at the GP’s office or at the patient's home. It makes it possible to reach frail patients, and the model can be implemented for diagnosis and management of AF in primary care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Helena Dominguez (HD); methodology, HD, Anne Frølich (AF); hardware and software, Cortrium ApS; formal analysis and investigation, Carsten Bamberg (CB), Caroline Thorup Ladegaard (CL); investigation, HD, CB, CL, Anne Blaabjerg Ahm Sørensen (AS), Dorthea Marie Jensen (DJ); data curation, CB, HD; writing—original draft preparation, CB, CL; writing—review and editing, HD,CB, CL, Mathias Aalling, DJ, Nina Kamstrup Larsen, Christoffer Læssøe Madsen, Sadaf Kamil, Henrik Guldbergsen, Thomas Saxild, Michaela Louise Schiøtz, Julie Grew, Luana Sandoval Castillo, Iben Tousgaard, Rie Rosenthal Johansen, Jokab Eyvind Bardram, AF; visualization, CB, HD, AF; supervision, HD, AF; project administration, HD; funding acquisition, HD, AF. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded with 13 mio DKK by the Innovation Fund, which is a foundation under the Ministry of Higher Education and Science grant number 6153-00009B.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was submitted to the Ethics Committee in the Capital Region and received approval from the Ethics Committe B, Capital Region, with reference: H-18052892

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Outcomes from the cluster-randomization study can be provided by the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the individuals who took the time to participate in the surveys and/or the interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Short version of interview guide.

Figure A1.

Short version of interview guide.

Appendix B

Table B1.

Analysis of interviews (example): transforming meaning units (quotes) into condensed meaning units without loss of core meaning; labelling the condensed meaning units with codes; grouping into categories; expressing categories’ meaning as themes1

Table B1.

Analysis of interviews (example): transforming meaning units (quotes) into condensed meaning units without loss of core meaning; labelling the condensed meaning units with codes; grouping into categories; expressing categories’ meaning as themes1

| Meaning Unit |

Condensed Meaning Unit |

Code |

Category |

Theme1

|

| “It wasn’t heavy or impractical in any way to wear the device. It was quite easy and didn’t bother me at all. I worked, went for a walk, and many other things.” |

Device is not bothering; easy to wear; activities as usual |

Everyday life with C3 monitor |

Comfort |

The device is user friendly / easy to use. |

| “My skin became very itchy when wearing it [the device].” |

Patches causing itchy skin reaction |

Source of annoyance |

| “You are kind of nervous whether the device might fall off. It actually did when I was playing golf. It was hot, and I was sweating a lot.” |

Device fell of due to sweating while playing golf. |

Technical problems |

Reliability |

References

- Writing Committee Members; Fuster, V.; Rydén, L.E.; Cannom, D.S.; Crijns, H.J.; Curtis, A.B.; Ellenbogen, K.A.; Halperin, J.L.; Le Heuzey, J.-Y.; Kay, G.N.; et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: full text: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation) Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace 2006, 8, 651–745. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Jones, D.M., et al., Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation, 2004. 110(9): p. 1042-6. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.J., et al., Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation, 1998. 98(10): p. 946-52. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, L.; Norberg, J.; Jansson, J.-H.; Bäckström, S. Estimating the prevalence of atrial fibrillation in a general population using validated electronic health data. Clin. Epidemiology 2013, 5, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potpara, T.S.; Polovina, M.M.; Marinkovic, J.M.; Lip, G.Y. A comparison of clinical characteristics and long-term prognosis in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with first-diagnosed atrial fibrillation: The Belgrade Atrial Fibrillation Study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 4744–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilaveris, P.E.; Kennedy, H.L. Silent atrial fibrillation: epidemiology, diagnosis, and clinical impact. Clin. Cardiol. 2017, 40, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, R.G. Atrial fibrillation and stroke prevention. N Engl J Med, 2003. 349(11): p. 1015-6. [CrossRef]

- Wachter, R.; Weber-Krüger, M.; Seegers, J.; Edelmann, F.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Wasser, K.; Gelbrich, G.; Hasenfuß, G.; Stahrenberg, R.; Liman, J.; et al. Age-dependent yield of screening for undetected atrial fibrillation in stroke patients: the Find-AF study. J. Neurol. 2013, 260, 2042–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, S.J., et al., Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med, 2009. 361(12): p. 1139-51. [CrossRef]

- Gladstone, D.J.; Bui, E.; Fang, J.; Laupacis, A.; Lindsay, M.P.; Tu, J.V.; Silver, F.L.; Kapral, M.K. Potentially Preventable Strokes in High-Risk Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Who Are Not Adequately Anticoagulated. Stroke 2009, 40, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.R., et al., Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med, 2011. 365(10): p. 883-91. [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.B., et al., Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med, 2011. 365(11): p. 981-92. [CrossRef]

- Giugliano, R.P., et al., Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med, 2013. 369(22): p. 2093-104. [CrossRef]

- Shahid, F.; Shantsila, E.; Lip, G.Y.H. Recent advances in the understanding and management of atrial fibrillation: a focus on stroke prevention. F1000Research 2016, 5, 2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubitz, S.A., et al., Long-term outcomes of secondary atrial fibrillation in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation, 2015. 131(19): p. 1648-55. [CrossRef]

- Filardo, G.; Hamilton, C.; Hamman, B.; Hebeler, R.F.; Adams, J.; Grayburn, P. New-Onset Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation and Long-Term Survival After Aortic Valve Replacement Surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2010, 90, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, A.; Dinh, D.; Dimitriou, J.; Reid, C.; Smith, J.; Shardey, G.; Newcomb, A. Preoperative atrial fibrillation is an independent risk factor for mid-term mortality after concomitant aortic valve replacement and coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 16, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlsson, A.; Fengsrud, E.; Bodin, L.; Englund, A. Postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing aortocoronary bypass surgery carries an eightfold risk of future atrial fibrillation and a doubled cardiovascular mortality. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2010, 37, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillarisetti, J.; Patel, A.; Bommana, S.; Guda, R.; Falbe, J.; Zorn, G.T.; Muehlebach, G.; Vacek, J.; Lai, S.M.; Lakkireddy, D. Atrial fibrillation following open heart surgery: long-term incidence and prognosis. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2013, 39, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaatz, S.; Douketis, J.D.; Zhou, H.; Gage, B.F.; White, R.H. Risk of stroke after surgery in patients with and without chronic atrial fibrillation. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 8, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, D.; Harrison, S.L.; Kolamunnage-Dona, R.; Lip, G.Y.H.; A Lane, D. The Atrial Fibrillation Better Care pathway for managing atrial fibrillation: a review. Europace 2021, 23, 1511–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, K.E.; Zwarenstein, M.; Oxman, A.D.; Treweek, S.; Furberg, C.D.; Altman, D.G.; Tunis, S.; Bergel, E.; Harvey, I.; Magid, D.J.; et al. A pragmatic–explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. J. Clin. Epidemiology 2009, 62, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, I. and J. Norrie, Pragmatic Trials. N Engl J Med, 2016. 375(5): p. 454-63. [CrossRef]

- Ladegaard, C.T.; Bamberg, C.; Aalling, M.; Jensen, D.M.; Kamstrup-Larsen, N.; Madsen, C.V.; Kamil, S.; Gudbergsen, H.; Saxild, T.; Schiøtz, M.L.; et al. Reaching Frail Elderly Patients to Optimize Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation (REAFEL): A Feasibility Study of a Cross-Sectoral Shared-Care Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 7383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Q.-L. The Frailty Syndrome: Definition and Natural History. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2011, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoon, Y.; Bongers, K.; Van Kempen, J.; Melis, R.; Rikkert, M.O. Gait speed as a test for monitoring frailty in community-dwelling older people has the highest diagnostic value compared to step length and chair rise time. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2014, 50, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rosted, E.; Schultz, M.; Dynesen, H.; Dahl, M.; Sørensen, M.; Sanders, S. The Identification of Seniors at Risk screening tool is useful for predicting acute readmissions. Dan Med J 2014, 61, A4828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Erlingsson, C.; Brysiewicz, P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 7, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).