1. Introduction

Sri Lanka which is located closer to the equator in the Southern hemisphere is a tropical island in the center of the Indian Ocean. Being on the end of the funnel-shaped Indian sub-continent, Sri Lanka is considered to have the highest biodiversity per unit area within the Asian region (MOE, 2012). Sri Lanka is one of the 36 biological hotspots along with the Western Ghats of India (Myers et al.,2000). It indicates both the vulnerability and the richness of the biodiversity in Sri Lanka as well as the threat that is found concerning biodiversity. The wide variety of ecosystems in Sri Lanka causes a high species density (number of species per 10,000 km2) for angiosperms, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals in the Asian Region (Dirzo & Raven, 2003; MOE, 2012). Sri Lanka has 453 avifaunal species, including 27 endemics out of 240 breeding residents. Although the endemic and threatened species are high among the hill country wet zones, the northern province dry zone area is fully occupied by the highest number of migrants in the country from early August to late April of each year (Wijesundara et al., 2017; MOE, 2012). The avifaunal distribution and diversity are at great risk due to the decrease in natural forest cover i.e., 19% in 2005, 33.0% in 2015, and 29.7% in 2017 (CEA and DWC, 2017), as a result of fast urban development (Katayama et al., 2015), and more importantly due to highway road infrastructure developments (Fahrig & Rytwinski, 2009).

The wet zone of Sri Lanka is marked as a distinct ecological hotspot in the World (Gunawardene et al., 2007) with its rich faunal and floral biodiversity. An avifaunal study at the St.Coombs tea estate, Sri Lanka indicated 87 bird species (12.6% E) (Kottawa-Arachchi and Gamage, 2015). Also, in the wet zone of Sri Lanka, Crow island in Colombo, is an urban coastal wetland recorded with 28 bird species (Amarasekara et al., 2021). But, the dry zone and the Northern part of Sri Lanka are also remarkably noted for their winter visitors during the migratory seasons of avifaunal species. It was observed that the wetlands and protected areas in the Northern coastal region of Sri Lanka are very important for various kinds of bird species in the world.

There are various avifaunal studies carried out in Vavuniya but no comprehensive studies done on the forest birds. There are 13 patch forest reserves belonging to the Vavuniya district which belongs to the Forest Department with a forest cover area of 1,238 km2 which represents 9.9% of the total forest cover of Sri Lanka (Mallawatantri et al., 2014). Even though it is like that, bird studies carried out in the Vavuniya are mostly based on tanks and their surroundings (Sivanesan & Anukulan, 2015; Sajitharan, 2003; Samith Indika Maddumage et al.,2019). These indicate that there is a knowledge gap about the bird diversity in the Pampaimadu area and a lack of information about the forest birds in the Vavuniya district. This study also helps to understand the influence of human habitats and bird diversity. In addition to that, also it allows us to study how habitat susceptibility affects tropical bird diversity.

Studies that are conducted in higher education institutes like universities relate to the avifaunal checklist are important to assess the composition as well as the importance of the strategic conservation plan that it performs. The institutions have a specific role in demonstrating the conservation of faunal and floral species with human interaction with the outer world. The study conducted at the state university Rajarata which is closer to the first sanctuary of the World Mihintale (Wimalasekara and, Wickramasinghe, 2010) in 2011 by Rathnayake et al., resulted in the observation of 80 bird species (2.5%E). It concludes with the mixture of vegetation types within the study site providing suitable habitats for different types of birds. Another study at the Eastern border of the Faculty of Applied Science, the University of Rajarata by Boperachchi and Wickramasinghe in 2017 resulted in the observation of 45 birds with (9%E). It also concluded that there was a significant increase in bird diversity in the semi-aquatic habitat rather than the edge area. A study by Sanjeewani and Perera in 2009 at Sabaragamuwa University, resulted in observing 77 bird habitats (10.4%E). It recorded the highest and lowest bird species diversity in the disturbed riparian shrubland habitat (H’=1.69) and woodland habitat (H’=1.38) respectively.

According to Miller & Spoolman (2014), avifaunal diversity can be considered a biological indicator of ecosystem stability since they are responding much quicker to changes in the environment. The concept of ‘using birds as indicators for recognizing land ecosystems rich in biological diversity has now gained wide global acceptance’ (O’Connell et al., 2000; Niemi & McDonald, 2004; Schulze et al., 2004). The changes in the environment which could cause by either natural or anthropogenic activities tend to influence the avifauna directly or indirectly. Thereby these changes can influence the avifaunal diversity, composition, density, abundance, occurrence, size, geographic range, habitat occupancy, age structure, sex ratios, or the proportion of birds that breed (Reijnen & Foppen, 1994). Therefore, along with some parameters, avifaunal abundance and diversity of species serve as ecological health indicators.

Hence, the light of the present study was to create a preliminary species checklist of avifaunal species present in the University of Vavuniya, Pampaimadu premises to create awareness and ensure sustainable wildlife conservation and management efforts. Further, avifaunal species were surveyed concerning the habitat distribution within the premises, and the community indices were calculated to understand whether anthropogenic factors influence bird diversity in an institution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

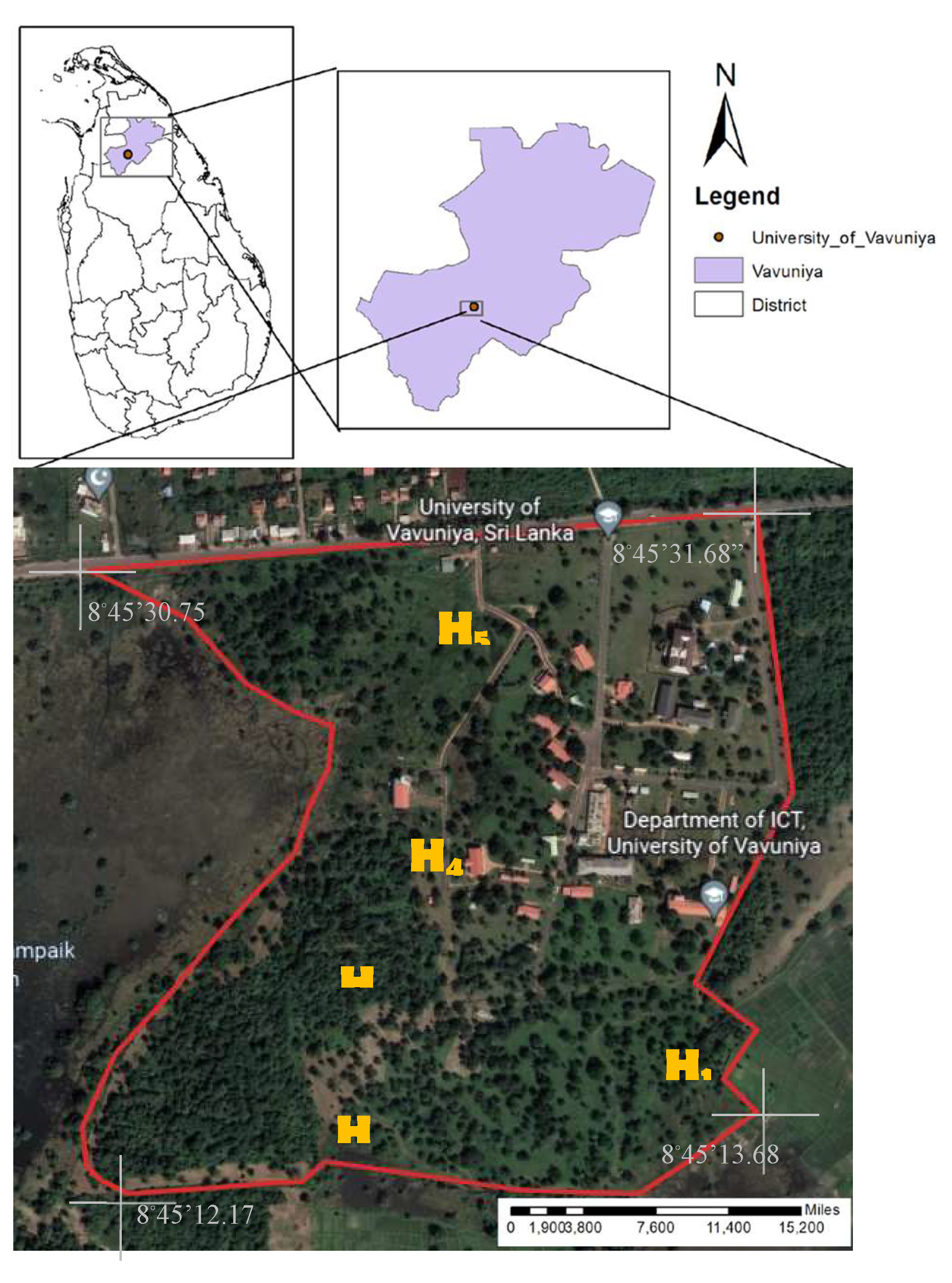

The study was conducted at the University of Vavuniya, Pampaimadu Premises. The State University has located 10 km from Vavuniya town, along the Vavuniya-Paranayankulam (A30) highway. The Pampaimadu premises consist of 65.0248 ha of an area with dominating natural dry-mixed evergreen forest patch.

The district is located within the dry zone which experiences a mean temperature of 28°C and an annual rainfall of 1400 mm. It also consists of 2 adjoined tanks along the boundary. The academic area was divided into five different habitats based on ecosystems available in the study area and segmented (

Figure 1).

The study points (

Figure 1) were used for the avifaunal survey during mid of March to July 2022. The habitat types were described based on the general observation of the vegetation in the study area (

Table 1). The first study point (H1) is the woodland-paddy land ecosystem which is located at the boundary of the university premises. H1 is a transitional zone for both paddy land and woodland and consists of dry mixed evergreen forest located on the South-Eastern side of the premises. The second point (H2) was the woodland-water catchment ecosystem which is adjacent water holding grounds that are found on the North-Western side along the forest patch attracting lots of water birds within the premises. The third study site (H3) was the forest habitat consisting of dry mixed evergreen forest surrounded by a jeep road. The fourth study site (H4) was the grassland with an inundated area. Grass species such as Indian goose grass (

Eleusine indica), Love grass (

Chrysopogon aciculatus), Mottu thana (S) (

Cyperus kyllingia), and Shame plant (

Mimosa pudica) and isolated trees such as Kumbuk (

Terminalia arjuna), Maila (

Bauhinia racemose) and Mango (

Mangifera indica) tree were dominated among the habitat. Part of this habitat was inundated during March and April, but it was completely dry after June and July 2022. The fifth study point (H5) was a managed garden with occasional trees which is along the faculty premises of Applied Science. There were occasional trees around the faculty including fruit trees such as

Syzygium samarangense,

Ficus benghalensis, and

Mangifera indica. It building opens up west to the forest patch. The dry mixed-evergreen forest trees were found within the Habitats of the study area.

2.2. Data collection methods

Data collection was continuously done from March to July 2022. Data were collected in two sessions. The morning session was from 0600hr to 0800hr while the evening session was from 1600hr to 1800hr. Both sessions were not conducted on the same day and one session per day was performed. Twenty replicates (n=20) were conducted on each habitat covering a total of 100 sampling events throughout the study period. Data were collected by the time-restricted point count method (15 minutes per point). The nearest data points were not observed on the same day due to avoid disturbance by walking around the habitat points. The observation duration was 10 minutes at each point after allowing a 5-minute settling period. Birds that fly towards the points were counted as a new observation and birds that fly away from the points were considered as already counted. Visual assessment of birds was only considered for the survey but not the calls of the birds. A few assumptions were considered i.e., birds do not approach the observer or flee during the observation period, birds are 100% detectable at the observer’s location, birds do not move from their location, and birds behave independently of one another are taken during this study. The survey was not carried out during bad weather times. Opportunistic observations during the study period along the university premises were added to the total bird list. Nikon 8×40 binoculars, Nikon B500, and Canon Supershot SX 60HS cameras were used to capture the avifaunal species whenever possible. Unidentified Bird species were identified using field bird guidebooks (Harrison & Worfolk, 1999; Kotagama & Ratnavira, 2010; Warakagoda et al., 2020) after taking field notes or photographs.

2.3. Data Analysis

To calculate the species diversity indices, the point-count method was adopted to obtain the relative or absolute abundance of the birds (Nalwanga

et al., 2012). The radius was taken as the until the far where clear visuals of birds could obtain in this study since there is enough distance present between two points without overlapping them. The point counts are set out systematically to represent the full range of habitats present in the wood. Species diversity was calculated by using two standard methods of Shannon-Weiner diversity index method (Shannon and Weaver, 1964) and Simpson’s diversity index (Simpson, 1949) method (

Table 2). Also, species evenness was calculated by using Simpson’s evenness method. Species richness was used in the following equation given in table 2. Species diversity variation among the different habitats was determined by using ANOVA. Species distribution was tested with chi-square for association and by measuring the Euclidean distances were dendrogram was drawn to find similarities among habitat’s similarity. All the statistical analysis was done using Minitab ver18.0.

3. Results

3.1. General

The total checklist recorded 93 species on the university premises with 80 birds from the point count method and 13 from the opportunistic observations (Error! Reference source not found.). Among the point count observations, 6 species are endemic; Sri Lanka Junglefowl (Gallus lafayettii), Sri Lanka Green-Pigeon (Treron pompadora), Crimson-fronted Barbet (Psilopogon rubricapillus), Crimson-backed Flameback (Chrysocolaptes stricklandi), Red-backed Flameback (Dinopium psarodes), and Sri Lanka Woodshrike (Tephrodornis affinis). While in the opportunistic observation, three bird species are endemic; Sri Lanka Grey Horn Bill (Ocyceros gingalensis), Sri Lankan Swallow (Cecropis hyperythra), and Brown-capped Pygmy woodpecker (Yungipicus nanus) making a total of 9 (9.7%) endemic birds within the university premises. The checklist indicates that a total of 12.58% avifauna is available in the University of Vavuniya, Pampaimadu Premises compared to the national checklist (MOE, 2012). The most abundant bird species was Rock Pigeon (Columba livia) (n=123) followed by Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis) (n=97) and Scaly-breasted Munia (Lonchura punctulata) (n=93). There are 44 avifaunal bird families observed with the most abundant bird family being Columbidae (13.6%) followed by Ardeidae (7.8%), Phasianidae (7.5%), and Estrildidae (7.0%). Other families with less than 5% of total occurrence.

According to the National Red List 2012 of Sri Lanka, in regard to National Conservation statuts (NCS), there are 7 NT, one CR (Columba livia) in wild and oneVU (Lonchura malacca) species, while as a Global Conservation status (GCS) 5 species are belongs to NT status.

3.2. Species Composition and Diversity in various habitats

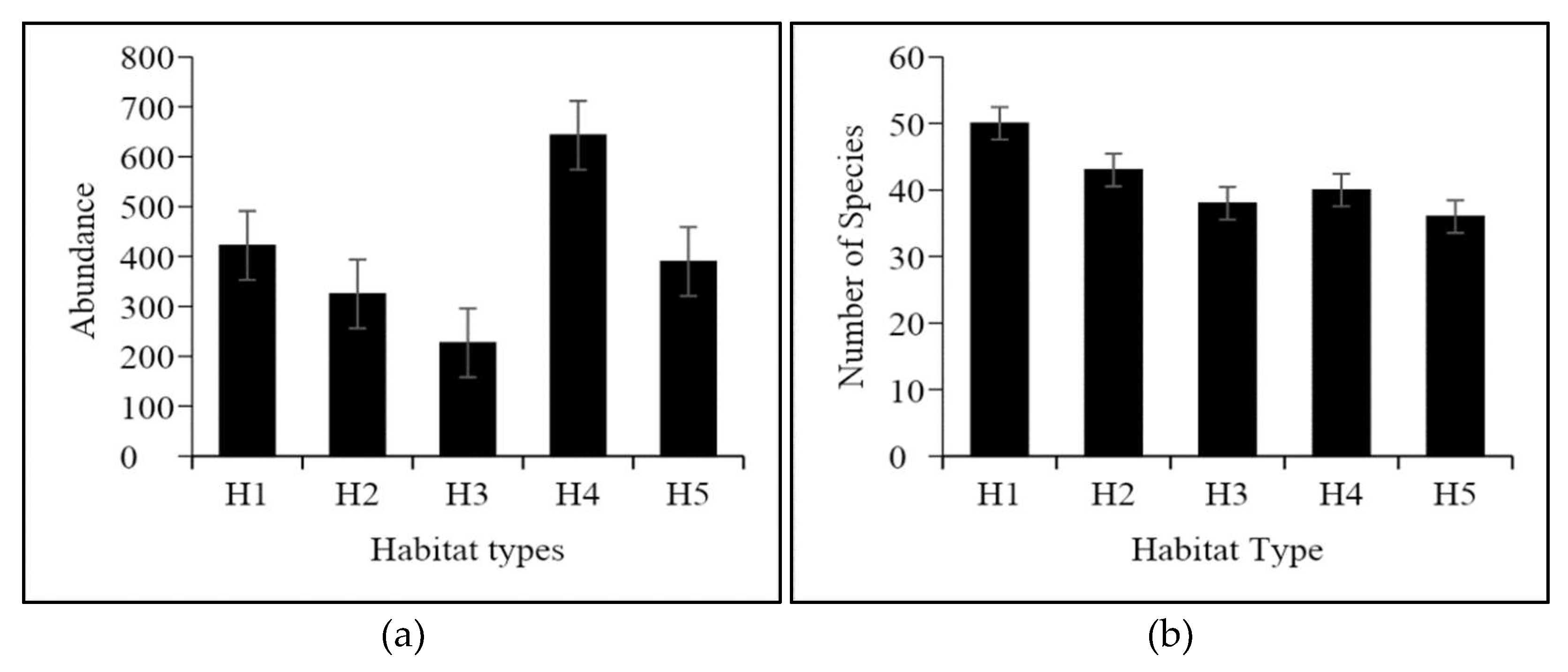

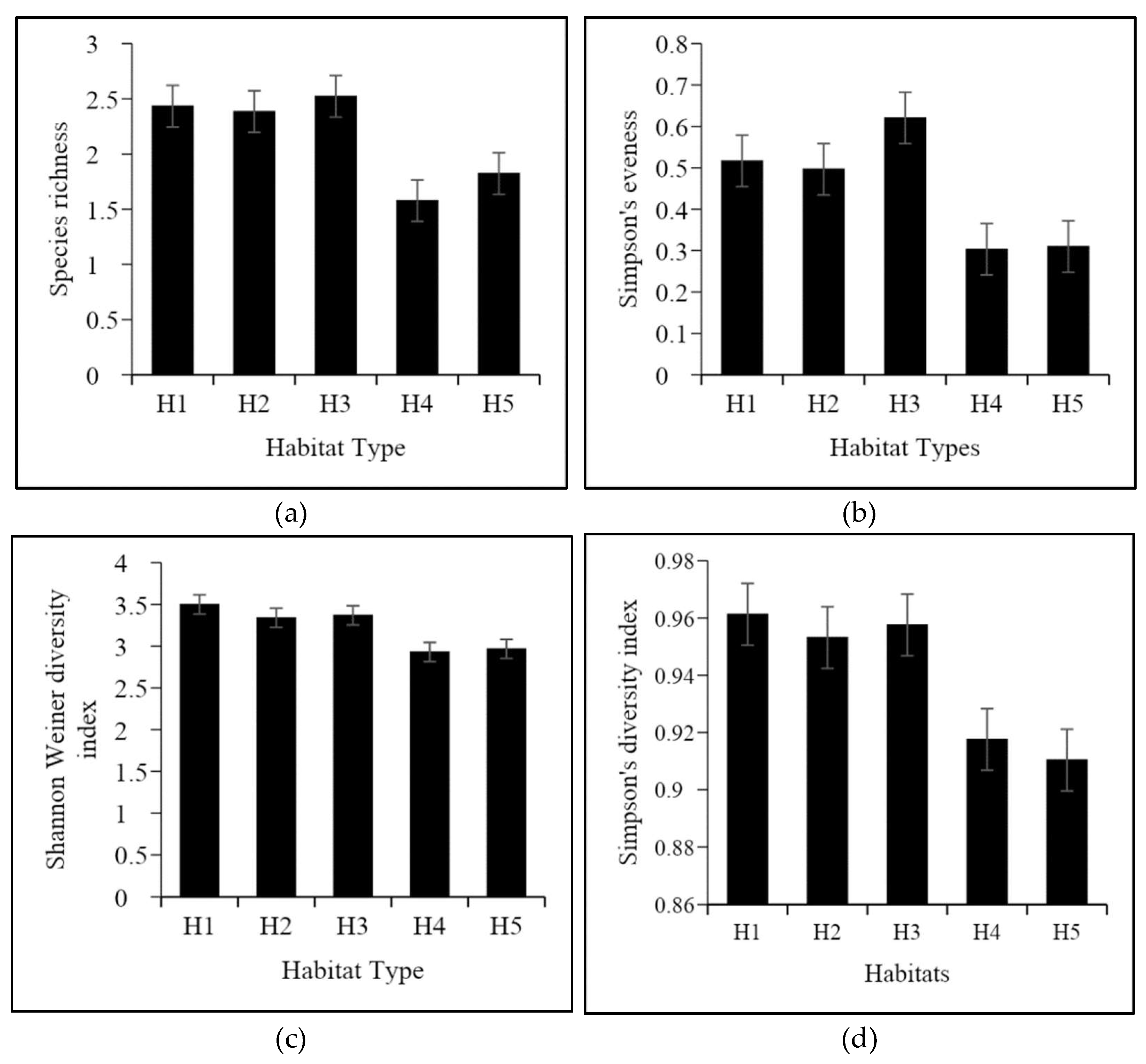

The highest number of species was recorded in the H1 (n=169) habitat and the highest abundance of species was recorded in the H4 (number of species=?) habitat type (Figure 3). The lowest abundance and number of species were recorded in H3 and H5 habitats respectively. Similarly, the highest Shannon Wiener and Simpson’s species diversity recorded in H1 (H’ =3.499, D= 0.961) followed by H3 (H’ =3.369, D= 0.957) and H2 (H’ =3.339, D= 0.953) (4 a and b). However, the highest species richness and evenness were recorded at the H3 (R= 2.522, E=0.621) and the lowest was recorded at the H4 (R=1.577, E=0.303) (Figure 4c and d).

Figure 3.

Distribution of the birds a) individual abundance in different habitats b) number of different species, recorded in five different habitat types among the University premises, Vavuniya.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the birds a) individual abundance in different habitats b) number of different species, recorded in five different habitat types among the University premises, Vavuniya.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the species diversity a) Shannon Weiner diversity index b) Simpson’s diversity index c) Species richness and d) Species evenness among the five different habitat types in the University premises, Vavuniya.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the species diversity a) Shannon Weiner diversity index b) Simpson’s diversity index c) Species richness and d) Species evenness among the five different habitat types in the University premises, Vavuniya.

Shannon Wiener and Simpson’s species diversity indices showed a corelative trend in the habitats. With a higher Shannon-Wiener index value, diversity will be higher which is measured by species richness and the average or evenness of individual distribution in the species. The same implies to Simpson’s index, that is with a more uniform distribution of various individuals, and the higher the index indicates a good diversity of the community.

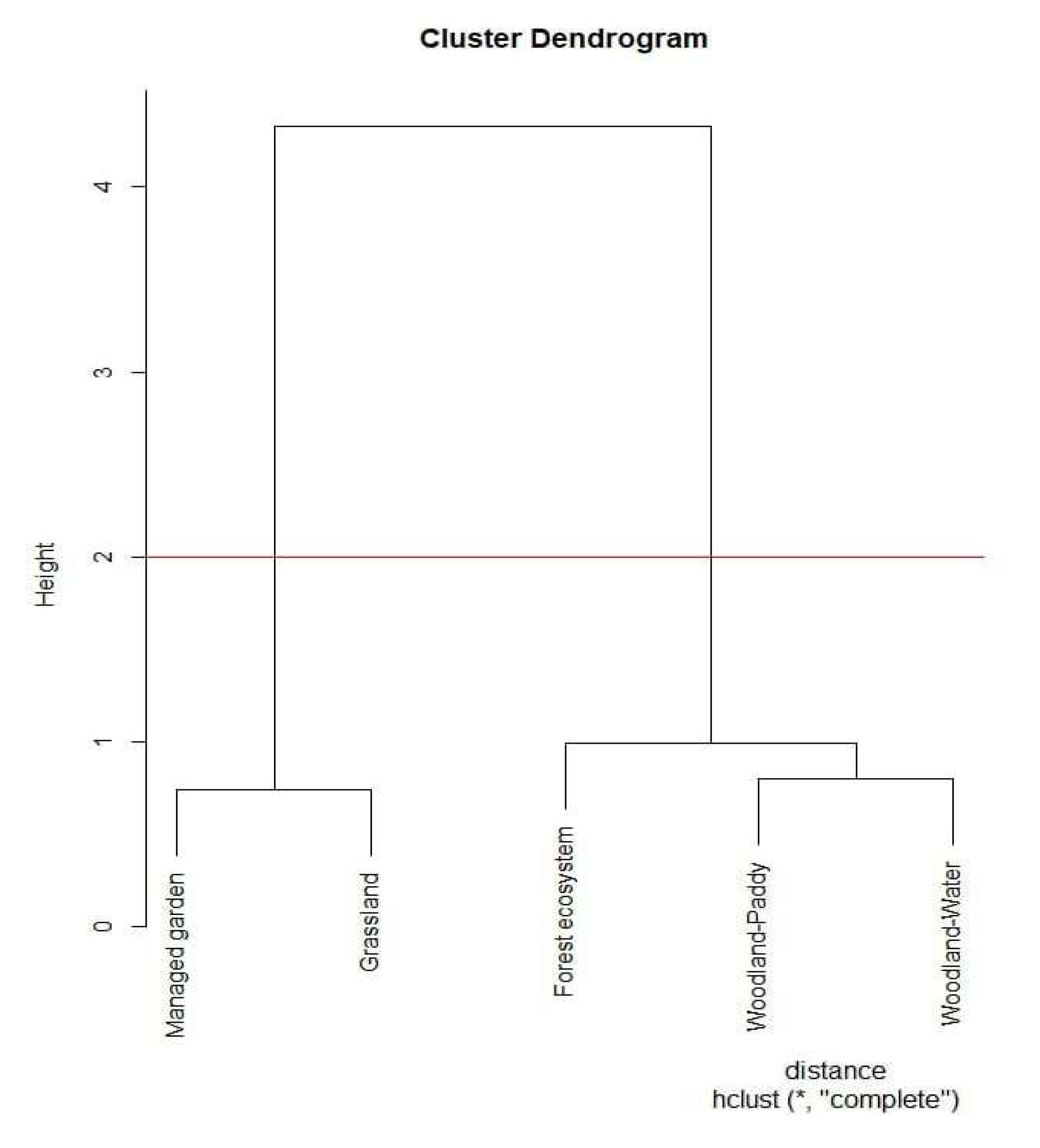

3.3. Habitat similarities in the study area

The dendrogram (Figure 6) shows that the similarity of the habitat types is within the study area in terms of their avifauna diversity. It showed that the Grassland with an inundated land ecosystem (H4), and the Manage Garden with Occasional trees (H5) are different from the H1, H2, and H3. Woodland-water habitat is categorized under the same while the cluster of both begins to approach the forest ecosystem at level 1. On the other hand, managing gardens and grasslands show many similarities. The niche of the birds could able to replicate in each of the clustered ecosystems.

Figure 4.

Cluster Dendrogram indicating the relationship between different habitats.

Figure 4.

Cluster Dendrogram indicating the relationship between different habitats.

4. Discussion

4.1. Species composition in their habitats in the University of Vavuniya, Pampaimadu premises

The Woodland-Paddy land ecosystem is highly occupied by the small-sized volery of avifaunal species from the family Estrildidae (11.1%), even though only two species of White-rumped Munia (Lonchura striata) and Scaly-breasted Munia (Lonchura punctulata) are seen in the particular family. In the H1 they dominate this land with their high abundance. The mixture of Dry mixed evergreen forest trees and the paddy land across the boundary of the University of Vavuniya, Pampaimadu Premises provides an ample amount of food as well as habitat resources to various avifaunal species. It can be the reason for the availability of food in nearby forest patches (Rathnayake et al., 2011). It is also observed that 49 bird species belong to 32 families within this habitat. It is the habitat that exhibits the highest number of species (Figure 3 b) which is also with the highest Shannon Diversity Index (3.499) among other habitats. But Simpson’s evenness is found almost equal to 0.5 which interprets that the habitat is filled with a mean of evenness among whatever species belongs to that particular area. At the University of Vavuniya, the H1 ecosystem is with the highest Shannon index (H’=3.49). It can be due to that, the human intervention on the premises is still at the beginning level since it is just promoted from the Vavuniya Campus of the University of Jaffna and the number of students studied is also low compared with the other two state universities. Due to that, the disturbance to the natural habitat as well as to the avifaunal species is still within a controllable range.

The water catchment area along with the forest makes the Woodland-Water catchment area ecosystem, highly occupied by the families of Ciconiidae (14.8%) and Phasianidae (11.1%). It indicates the water birds Asian Openbill (Anastomus oscitans), Woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus) and Painted Stork (Mycteria leucocephala) dominate this habitat rather than woodland avifaunal species. This location is often used by the birds since water can be available during the dry season also. And this location also acts as a corridor where the animals could move in between thick dense vegetation and the sparse woodland. Sri Lankan Woodshrike is an endemic bird observed in high frequency in this habitat. The availability of agricultural lands near the boundaries of the premises leads to the high availability of Indian Peafowl (Pavo cristatus) in this habitat. This study site has the second lowest abundance of species but it ranked third in other measured diversity indices.

The forest ecosystem is highly dominated by the family Columbidae (15.0%). A total of 22 families of 38 avifaunal species were found and that study point has the lowest abundance and highest species richness and evenness. It shows that it was observed low abundance of birds with a high diversity and evenly distributed. This can be due to increased predatory risks for the birds inside the thick forest patch. Interestingly out of 6 observed endemic species, 5 species were found to be observed in this habitat. And also, all the birds of prey; Crested Serpent-Eagle (Spilornis cheela), Brahminy Kite (Haliastur indus), Black Eagle (Ictinaetus malaiensis), and Shikra (Accipiter badius) were observed only in this habitat. Daniels (1989), indicated that, an increase in bird species diversity when forests are disturbed rather than on undisturbed land. The H3 study area has a denser understory and canopy than the other four study points. Therefore, it has a higher observer visibility bias than compared to other study points. Moreover, that habitat used to hide the birds from predator species as well as predator birds used to hide there before their hunting. That both reasons reduce the bird visibility during the observation.

Manage garden with Occasional trees is highly dominated by the family Columbidae (28.8%), especially with the Rock Pigeon (Columba livia) and Scaly-breasted Munia (Lonchura punctulata). That can be due to their niches mainly around the human settlements including buildings, and garden trees. It consists of 40 avifaunal species with 24 families. This habitat is recorded for its highest species abundance among other habitats. Although it has the lowest Simpson's evenness which indicates that, this habitat is rich with its species' evenness compared with other habitats. Endemic Species such as Sri Lanka Green-Pigeon (Treron pompadora), Common Tailorbird (Orthotomus sutorius), Black-backed Dwarf-Kingfisher (Ceyx erithaca), Eurasian Collared-Dove (Streptopelia decaocto) and Rock Pigeon (Columba livia) are only recorded in this habitat. Also, synanthophic avifaunal species (Menon & Mohanraj, 2016) like house crow (Corvus splendens), yellow-billed babbler (Argya affinis), common myna (Acridotheres tristis) which are found in-between the buildings mainly for feeding, drinking with the human-influenced foods, are to be found within these areas.

Grassland with an inundated land ecosystem is highly found with the family of Ardeidae (38.2%), especially with Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis) species. This habitat consists of 36 avifaunal species belonging to 25 families. It is the only habitat that is with no endemic bird observed in the study area. The landscape and the vegetation of this habitat make it unique to most of the avifaunal species at the University of Vavuniya, Pampaimadu premise. Birds commonly feed on marshy lands like, Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis), Intermediate Egret (Ardea intermedia), Indian Pond-Heron (Ardeola grayii), Little Egret (Egretta garzetta), Glossy Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus), Lesser Whistling-Duck (Dendrocygna javanica), Small Minivet (Pericrocotus cinnamomeus) and Purple Heron (Ardea purpurea) were found only on this habitat. The inundation of land with rainwater seems to control the availability of the bird species and their abundance in this habitat. The grasslands also provide habitats as the nesting sites for birds including Yellow-wattled Lapwing (Vanellus malabaricus) and Red-wattled Lapwing (Vanellus indicus) which were observed during the study time. A large part of the front entrance area was maintained as a grassland ecosystem by the administration. This allows a lot of insectivores avifaunal to this habitat. Rathnayake et al., (2011) indicated that terrestrial insectivores are more abundant in grasslands compared to other habitats. It influences a variety of bird species that are found in a particular area due to the availability of seeds as their feeding material.

There are some species commonly found in all the habitats. The Spotted Dove (Streptopelia chinensis), Orange-breasted Green-Pigeon (Treron bicinctus), White-throated Kingfisher (Halcyon smyrnensis), Green Bee-eater (Merops orientalis), Greater Coucal (Centropus sinensis), Indian Peafowl (Pavo cristatus), Red-vented Bulbul (Pycnonotus cafer), and Indian Robin (Copsychus fulicatus) were found in all locations in the University of Vavuniya, Pampaimadu Premises regardless of the habitat.

4.2. Importance of the land area in the University of Vavuniya, Pampaimadu Premises

Protected areas, like national parks, and sanctuaries are important wildlife locations that help to maintain a healthy faunal and floral population in Sri Lanka. The avifaunal species in the dry zone of Sri Lanka are mostly observed along with the tanks due to the water shortage during the long summer. Wilpattu National Park recorded 137 bird species belonging to 49 families in 2007 by Weerakoon and Goonatilleke. In there only 12% was recorded as endemic with the total checklist of Sri Lanka. While in the Mihintale Sanctuary of Sri Lanka, 130 birds were recorded by Wimalasekara and Sriyani in 2010 but only with less than 6% endemic or proposed endemic species. A 7-year study in the peripheral areas of Maduruoya National Park resulted in a record of 196 bird species with almost 5% of endemic birds Gabadage. D.E., et al., in 2015. Another study in the Sigiriya sanctuary in 2014 by Dissanayaje et al., indicates the availability of 165 species with 5.4% of endemic and proposed endemic bird species. The Peak Wilderness Sanctuary is the only sanctuary in Sri Lanka recorded with all the endemics with a total avifaunal population of 173 species (100%E) (Karunarathna et al., 2011). But, the study at the University of Vavuniya, Pampaimadu premise for 4 months results in 12% of endemic birds with the checklist on the premises while almost 35% with the total national checklist (Kotagama, et al., 2010). This shows the importance of managing the presently available natural habitat and the state of the University premises. The availability of a reserved forest in front of the University premises is important to maintain that it can act as a buffer for the bird species to maintain their healthy state of diversity and abundance.

4.3. Study about the tropical land avifaunal diversity in the Vavuniya

The avifaunal studies that were previously carried out in the Vavuniya were mostly associated with the waterbody only. Due to that, the checklist of land birds seems to be found as a gap in the Vavuniya District. Sivanesan and Anukulan (2015) indicate that a record of 32 and 54 birds were found in the Vairavapuliyankulam and Kombuvaithakulam respectively where he compared the disturbed and undisturbed tanks. At the same time, Samith Indika et. al., (2019) recorded 15 water bird species in the Kalkundamaduwewa tank. Another piece of literature by De Zoysa and Sundarabarathy in 2013 gives an observation of 71 avifaunal species in the Kammalakkulama Tank, Mihintale with three endemic birds. But this study indicates 92 total species including non-habitat observation but only about 20% of birds are related to the water birds. The availability of adjacent inundated water storage places and tank makes the availability of these water birds diverse on the premises.

5. Conclusions

Habitat mixed with woody plant points recorded the highest diversity. Grassland mixed habitats recorded the most abundance of the species but less diversity. Some species were recorded as lard numbers of groups, especially in the water and marshy lands. Endemic birds were highly observed in the forest habitat. As a newly established university, it has fewer development activities and remains more forest area which is helping to more bird diversity in the Pampaimadu area. However, as it is a preliminary study it is recommended to study further during the following years and compare with this checklist for further light knowledge.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1: Avifaunal species composition in the University of Vavuniya, Pampaimadu Premises; Figure 1: Some of the observed avifaunal species in the study area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.T. and H.M.P.A.W.; methodology, H.K.N.S and K.T.; software, K.T.; formal analysis, H.K.N.S.; investigation, H.P.P.A.W. and K.T.; writing—original draft preparation, K.T.; writing—review and editing, K.T. and H.K.N.S.; visualization, H.K.N.S. and K.T.; supervision, H.K.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are great fully acknowledge to Dr. S. Wijeyamohan and Mr. G. Naveendrakumar, Senior lecturers of the Department of Bio-science, Faculty of Applied Science, University of Vavuniya for their support to attain a fruitful study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Amarasekara, E. A. K. K., Jayasiri, H. B., Amarasiri, C. (2021). Avifaunal Diversity in Urban Coastal Wetland of Colombo Sri Lanka. Open Access Library Journal, 8(3), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Bopearachchi, D., Wickramasinghe, S. (2015, October). Avifaunal Diversity in Three Selected Habitats, at the Eastern Boarder of the Faculty of Applied Sciences of Rajarata University, Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of International Forestry and Environment Symposium (Vol. 20). [CrossRef]

- CEA and DMC (2014). Sri Lanka’s Forest Reference Level submission to the UNFCCC, Central Environment Authority and Disaster Management Center, Sri Lanka, ISBN: 978-955-9012-55-9.

- Daniels. R.J.R., (1989). A conservation strategy for the birds of the Uttara Kannada district. M.Phil. Thesis, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore.

- De Zoysa, H. K. S., Sundarabarathy, T. V. (2015, October). Avifaunal Diversity and Abundance at Kammalakkulama Tank in Mihintale, Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of International Forestry and Environment Symposium (Vol. 20).

- Dirzo, R., Raven, P. H. (2003). Global state of biodiversity and loss. Annual review of Environment and Resources, 28(1), 137-167.

- Dissanayake, D. S., Wellappuliarachi, S. M., Jayakody, J. A. H. U., Bandara, S. K., Gamagae, S. J., Deerasingha, D. A. C. I., Wickramasingha, S. (2014). The avifaunal diversity of Sigiriya Sanctuary and adjacent areas, North Central Province, Sri Lanka. BirdingASIA, 21, 86-93.

- Fahrig.L. and Rytwinski.T., “Effects of roads on animal abundance: an empirical review and synthesis,” Ecology and Society, vol. 14, no. 1, 2009.

- Gabadage, D. E., Botejue, W. M. S., Surasinghe, T. D., Bahir, M. M., Madawala, M. B., Dayananda, B., Karunarathna, D. S. (2015). Avifaunal diversity in the peripheral areas of the Maduruoya National Park in Sri Lanka: With conservation and management implications. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity, 8(2), 121-132. [CrossRef]

- Gunawardene, N. R., Daniels, A. E., Gunatilleke, I. A. U. N., Gunatilleke, C. V. S., Karunakaran, P. V., Nayak, K. G., ... Vasanthy, G. (2007). A brief overview of the Western Ghats--Sri Lanka biodiversity hotspot. Current Science (00113891), 93(11).

- Harrison. J and Worfolk.T, Field Guide to the Birds of Sri Lanka, Field Guide to the Birds of Sri Lanka, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 1999.

- Karunarathna, D. M. S. S., Amarasinghe, A. T., Bandara, I. N. (2011). A survey of the avifaunal diversity of Samanala Nature Reserve, Sri Lanka, by the Young Zoologists’ Association of Sri Lanka. Birding Asia, 15, 84-91.

- Katayama. N., Osawa. T., Amano. T., and Kusumoto. Y., “Are both agricultural intensification and farmland abandonment threats to biodiversity? A test with bird communities in paddy dominated landscapes,” Agriculture, Ecosystems Environment, vol. 214, pp. 21–30, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Kotagama. S., and Ratnavira. G., An illustrated guide to the birds of Sri Lanka, Field Ornithology Group of Sri Lanka, 2010.

- Kottawa-Arachchi, J. D., Gamage, R. N. (2015). Avifaunal diversity and bird community responses to man-made habitats in St. Coombs Tea Estate, Sri Lanka. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 7(2), 6878-6890. [CrossRef]

- Mallawatantri, A., Marambe, B., Skehan, C. (2014). Integrated strategic environmental assessment of the northern province of Sri Lanka final report. Central Environmental Authority, Disaster Management Centre, Sri Lanka.

- Menon, M., Mohanraj, R. (2016). Temporal and spatial assemblages of invasive birds occupying the urban landscape and its gradient in a southern city of India. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity, 9(1), 74-84. [CrossRef]

- Miller. G.T., and Spoolman. S.E., Living in the Environment: Concepts, Connections and Solutions, 2014.

- MOE 2012. The National Red List 2012 of Sri Lanka; Conservation Status of the Fauna and Flora. Ministry of Environment, Colombo, Sri Lanka. viii + 476pp.

- Myers. N, Mittermeler. R. A., Mittermeler. C. G., Fonseca da. G. A. B., and Kent. J., “Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities”, Nature, vol. 403, no. 6772, pp. 853–858, 2000.

- Nalwanga, D., Pomeroy, D., Vickery, J., Atkinson, P. W. (2012). A comparison of two survey methods for assessing bird species richness and abundance in tropical farmlands. Bird Study, 59(1), 83-95. [CrossRef]

- Niemi. G.J., and McDonald. M.E., “Application of ecological indicators,” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 89–111, 2004. [CrossRef]

- O’Connell. T.J., Jackson. L.E., and Brooks. R.P., “Bird guilds as indicators of ecological condition in the central Appalachians,” Ecological Applications, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 1706–1721, 2000.

- Rathnayake, D. K., Sandunika, I. A. I., De Zoysa, H. K. S., Wickramasinghe, S. (2011, November). Avifaunal diversity in Faculty of Applied Science premises Rajarata University of Sri Lanka. In Conference paper presented at: 2nd Annual Research Symposium. Faculty of Applied Sciences, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka. [CrossRef]

- Reijnen. R., and Foppen.R., “The effects of car traffic on breeding bird populations in woodland. I. evidence of reduced habitat quality for willow warblers (Phylloscopus trochilus) breeding close to a highway,” Journal of Applied Ecology, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 85–94, 1994. [CrossRef]

- Sajitharan, T. M. (2003). comparative study of the diversity of birds in three man-made reserviors in Vavuniya, Sri Lanka.

- Samith Indika Maddumage, M. R., Akther, M. S. R., Aashifa, M. A. R., Mohideen, A. H., Tharani, G. OPAL., Naveendrakumar, G. (2019). Assessment of Waterbird Composition in Kalkundamaduwewa Tank at Vavuniya, Sri Lanka.

- Sanjeewani, H. N., Perera, M. S. J. (2009). Preliminary Study on Avifaunal Diversity in the Sabaragamuwa University Premises, Belihuloya, Sri Lanka. In Abstract of 1st National Symposium on Natural Resources Management-NRM 2009 (p. 78). Sabaragamuwa University of Sri Lanka Belihuloya.

- Schulze. C.H., Waltert. M., Kessler. P.J., “Biodiversity indicator groups of tropical land-use systems: comparing plants, birds, and insects,” Ecological Applications, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 1321–1333, 2004.

- Sivanesan, K. S., Anukulan, W. (2015). Impact of Land Use Changes on Bird Diversity: A Comparative Study of Disturbed and Undisturbed Tanks in The Vavuniya District. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Environment Management and Planning. Colombo: Central Environmental Authority (CEA), Sri Lanka.

- Warakagoda, D., Inskipp, C., Inskipp, T., Grimmett, R. (2020). Birds of Sri Lanka: helm field guides. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Weerakoon, D. K., Goonatilleke, W. L. D. P. T. S. A. (2007). Diversity of avifauna in the Wilpattu National Park. Siyoth, 2(2), 7â.

- Wijesundara, C.S.,Warakagoda, D., Sirivardana, U., Chathuranga, D., Hettiarachchi, T.,Perera, N., Rajkumar, P., Wanniarachchi, S and Weerakoon G. (2017b). Diversity and conservation of waterbirds in the northern avifaunal region of Sri Lanka. Ceylon Journal of Science 46: 143-155. [CrossRef]

- Wimalasekara, W. C. S., Wickramasinghe, S. (2010). Avifaunal diversity in the Mihintale sanctuary of Sri Lan.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).