Introduction

Research has established significant economic value accrues to society through investing in higher education to develop wealth creating human capital (Hanushek, 2016; Leslie and Brinkman, 1988; Lin, 2004). Together with the knowledge economy, the demand for human capital has increased leading to global expansion in higher education enrolments (Altbach et al., 2019).

With both developed and developing nations education state budgets limited, private sector is investing in higher education (Altbach et al., 2019; Kallio et al., 2016). As a result, developed nation public funded higher education have increased fees and are generating income through research, consulting and industry partnerships (Altbach et al., 2019). Poorer developing nations students cannot afford these higher fees. Developing nations need to also catch up with developed western nations by creating homegrown human capital to narrow the technology gap to make them attractive destination for employment creating foreign direct investments (Bloom et al., 2006). To close this gap, many developing nations like Malaysia have set up low cost regional higher education hubs to attract foreign developed nation universities to offer their reputable degree programs run by privately funded local universities (Grapragasem, Krishnan, & Mansor, 2014). Malaysia also introduced equivalent student financial aid programs in the form of low-cost education loans to enhance enrolment (Perna, 2006).

However, both developed and developing nation higher education face intense competition for student enrolments. Developed nation higher education have lost substantial students from developing nations and have to compete for enrolment with other local higher education for the limited regional student population as is similarly the case for expansion of education hubs in developing nations that compete regionally (Knight, 2012).

This intense competition for student enrolment has led to the marketisation of education (Slaughter et al., 2004). This competition entails providing satisfying experiences to students as paying customers similar to that provided to commercial market customers for goods and services. This paper argues that higher education inadvertently resort to stress-free teaching and learning to foster future enrolment.

Pioneering research on marketisation of education show that this market ethos is ingrained in all aspects of higher education including research, teaching, learning and administration (Slaughter et al., 2004). However, the marketisation of education leads to numerous concerns. These concerns include poor acquisition of cognitive skills (Hanushek, 2016), student emphasis on passing tests (Voss et al., 2007), deterioration of quality assurance (Altbach et al., 2019), damage to teaching and learning pedagogy (Nixon et al., 2018), passive learning (Herrmann, 2013) and once rigorous lecturers transforming into popular lecturers to maintain employment (Tomlinson, 2017).

In spite of these concerns, highly reputable degrees are awarded implying that their graduates fulfil human capital requirements of potential employers. This belief is also premised on incorporating internships with industry to narrow the gap between higher education learning and businesses practices (D’abate et al., 2009). Students, employers and higher education show overall positive effects of internships (Sanahuja and Ribes, 2015). However, employers see a mismatch with graduate competences falling short of human capital needs (Ebelha et al., 2020). To the best knowledge of this author, no research to date can explain this anomaly.

This gap can be addressed by asking the research questions : Has the marketisation of higher education led to nominal human capital development? Can substantive human capital be developed in the new normal of marketisation of higher education?

To answer these questions, learning outcomes desired by future employers were compared for two teaching and learning approaches for a mandatory business ethics course namely student as customer (n= 497) and employer as customer (n= 355). An adaptation of randomised control trials was used to make this comparison (Barneejee, 2019). The paper argues that student as customer approach leads to nominal learning outcomes whilst employer as customer approach leads to substantive learning outcomes desired by employers.

The main theoretical contribution is to extend the existing model for teaching and learning outcomes to emphasise substantive human capital development desired by employers. The main practical contributions include teaching and learning pedagogy based on substantive human capital development, robust moderation process, renaming student satisfaction survey to human capital development survey and lecturer performance assessment based on learning outcomes.

Literature Review

The relevant literature on marketisation of education will be reviewed to answer the research questions.

Human Capital and Economic Development

The fourth industrial revolution heralds the knowledge economy where human capital is the key driver of wealth creating technological innovations that drive economic development. Higher education enable learning or the acquisition of knowledge to occur more rapidly (Arrow, 1961). Nations rely on them to produce human capital to drive economic development in a knowledge economy. However, there is a clear shortfall in human capital desired by employers (Ebelha et al., 2020).

In 1990s, the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), advocated transformation of higher education as promoters and executors of national innovation policies (Kallio et al., 2016). Accordingly, the United Kingdom (UK) proposed a research excellence (RE) framework to drive technological innovation to transition from slow growth to fast growth and thereafter a steady rate of economy growth (Gunn, 2018; Solow, 1987). This innovation approach enables business firms to acquire competitive advantage to sustain economic development.

According to the World Bank, higher education is instrumental in building skills that underpins economic growth and competitiveness of nations wealth creating institutions (Bloom et al., 2006). These skills include cognitive skills leveraging knowledge especially in science and technology, research skills and collaboration skills.Howeverl, developed and developing nations higher education face intense competition for student enrolment (Knight, 2012) leading to the marketisation of education.

Student as Customer

Marketisation of education leads to higher education devoting huge resources to marketing of programs, brand building and customer service with the goal of providing satisfying teaching and learning environment for the student customers (Brown and Carasso, 2013, Gunn, 2018).

The main objective is sustainable enrolment. Coupled with higher education adopting student centred approach to teaching and learning as advocated by Lea et al., (2003), annual student satisfaction surveys (SSS) were introduced to obtain feedback that will improve student satisfaction in all aspects of teaching and learning. Accordingly, many student satisfaction surveys were developed to mimic similar ones for products and services based on Fornell et al.’s (1996) American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI). This paper argues that this feedback is used to enhance stress-free teaching and learning rather than substantive learning.

Student Satisfaction Survey

SSS originally measured teaching quality of academics, classroom delivery, quality of academic feedback and interpersonal relationships (Hill et al., 2003). Today, SSS include learning objective, organisation and buildup of learning materials, lecturer presentation skills, lecturer guidance (Spooren et al., 2007), stimulating and facilitating learning environment, public praising and objective assessment criteria (Malouff et al., 2010). These determinants of teaching excellence (TE) should stimulate learning through engaging the cognitive and creative aspects besides meeting professional requirements of future jobs (Griffioen et al., 2018).

However, the introduction of research excellence (RE) framework led to total teaching time falling to 40 percent by 2013, prompting UK to introduce a teaching excellence (TE) framework in 2015 (Willetts, 2013). The SSS score that assesses academics ability to stimulate learning was expanded in UK’s 2015 TE framework to include assessing learning environment and learning gains or outcomes that contribute to work readiness and personal development (Gunn, 2018). Accordingly, this paper argues that higher education should focus on learning outcomes to foster employability.

Educator Professionalism

The SSS score was logically used to assesses academics ability to stimulate learning since it provides an objective assessment that contributes to career development and remuneration (Gunn, 2018; Kallio et al., 2016).

However, the emphasis on student as customer has led to passive learning by students (Herrmann, 2013) and once rigorous and professional educators transforming into popular ones to attain high SSS scores to maintain employment (Tomlinson, 2017). Together these have implications on employability.

Employability

Short-term graduate employment metrics is increasingly adopted by higher education as a strategic goal (Jackson and Bridgstock, 2021).

There is common agreement on skills expected by employers of higher education graduates namely cognitive skills as well as technical application and relational skills (Singh et al., 2022; Suleman, 2018). However, students emphasise leadership and authority, discipline specific knowledge and internship experience (Lisa et al., 2019).

This mismatch in expectations together with students passive learning and focus on passing test, arising from student as customer approach will potentially lead to nominal human capital development. This unintentional outcome will undermine the role of higher education institution in developing human capital desired by future employers. This paper argues that adopting employer as customer approach will lead to substantive human capital development.

Employer as Customer

This approach reframes the customer as the employer consistent with higher education role of developing human capital desired by future employers. Human capital compasses social capital, cultural capital, psychological capital, scholastic capital, market-value capital, and discipline specific skills (Donald et al., 2019).

The employer as customer approach uses problem based learning (PBL) which is increasingly adopted globally, as it is conducive to deep learning with students intrinsically motivated to understand what is being taught (Dolmans et al., 2016). In addition, PBL entail discussing real-world business problems through application of discipline specific knowledge (Dolmans et al., 2016) that imparts competence desired by future employers.

Theoretical Model of Teaching and Learning

This study compares both approaches in relation to well established theoretical model on teaching and learning. The emphasis is on learning outcomes that contribute to work readiness and personal development according to UK TE framework (Gunn, 2018).

Before 1990s, Universities focused on Humboltian research and teaching, with academics having the freedom and autonomy to pursue their passion for originality and independent thinking in their quest for universal values of knowledge and truth (Kallio et al., 2016). In this quest, academics develop in students critical thinking and acquisition of a broad perspective of knowledge (Gunn, 2018).

However, the marketisation of higher education inadvertently transformed the Humboltian educator as expert and in full control of the education experience towards one ensuring student customers receive satisfying teaching and learning experiences (Lažetić, 2019; Reynolds and Dang, 2017). The resulting consequences are serious. Once rigorous lecturers are transforming into popular lecturers (Tomlinson, 2017). This transformation is damaging to teaching and learning pedagogy (Nixon et al., 2018).

Both approaches in this study use the same Teaching excellence (TE) framework encompassing both declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge (Banks and Millward, 2007). Declarative knowledge deals with facts, figures, rules, relations and concepts in a task domain that are readily accessible if prompted by specific questions. Procedural knowledge refers to steps, procedures, sequence of actions that are often acquired through practice when performing skills-based tasks as adopted in workshops of this study.

Learning outcomes have become important consistent with employer expectations. 92 percent of 400 employers surveyed identified critical thinking as an important skill for workforce (Casner-Lotto and Barrington, 2006). Similarly, for cognitive skills as well as technical application and relational skills (Singh et al., 2022; Suleman, 2018). These learning outcomes include higher order critical thinking skills that enable logical thinking, problem solving and decision making (Butler, 2012; Haplern, 2003). In practice it entails, evaluating evidence, analysing arguments, understanding its implications and consequences and producing alternative arguments (Liu et al., 2014) as employed in this study for both approaches.

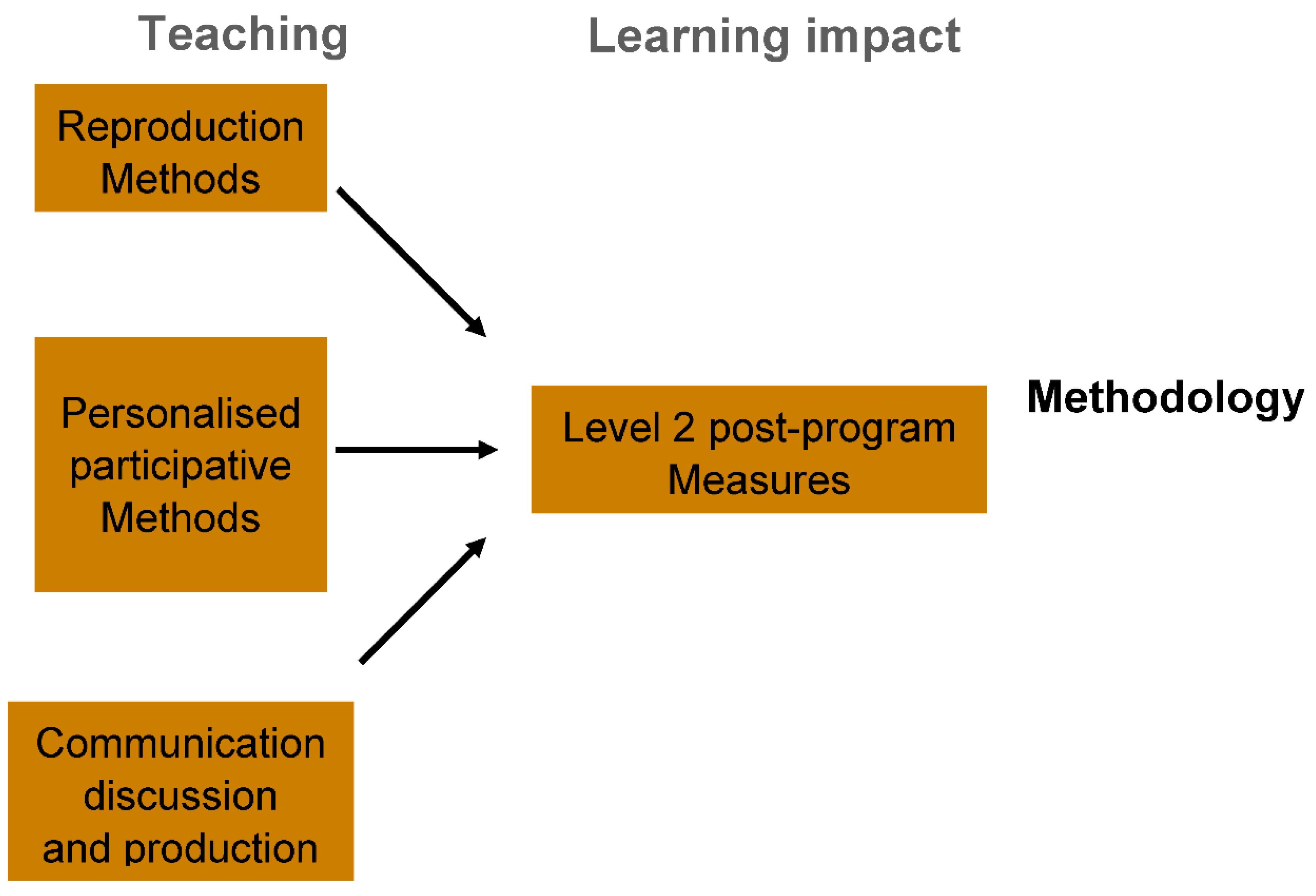

Both approaches share similar hybrid model to teaching and learning (figure 1) that has been adopted globally by most reputable higher education (Nabi et al., 2017). In today’s information age with ubiquitous information technology tools available in a digitally connected world both approaches also increasingly employ blended learning (Nortvig et al., 2018).

Figure 1.

Hybrid teaching and learning model.

Figure 1.

Hybrid teaching and learning model.

The hybrid model incorporates all the teaching methods to produce the most common level two learning impact namely post program measures of learning from summative assessments as used in this study. Reproduction methods entail lectures, readings etc. Personalised participative methods entail interactive searches, simulations etc. Communication discussion and production entails debates, discussions, portfolios, assignments etc. These teaching methods prepare students for learning outcomes that will be measured in summation assessment of final examination of this study for both approaches.

University A adopts UK Teaching excellence framework that fosters fair competition for student enrolment through providing data on course content, teaching methods, class size, educators’ qualifications and future careers to enable students to make informed choices (Gunn, 2018).

University A like other higher education located in education hub, provides low cost alternative to studying in UK to students from Asia, Africa and the Middle East that aspire to obtain high quality British degrees (Grapragasem, Krishnan, & Mansor, 2014).

University A, is licensed to award business degrees of a top ranked UK University and is in the path to be accredited by US based Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) to gain recognition of its degree elsewhere globally including the US .

AACSB learning outcomes are used by University A for a number of its business courses including business ethics. Business Ethics course was chosen as it provides a complete population of business school students from all Bachelors of science programs including in marketing (BMKT), financial analysis (BFA), financial economics (BFE), accounting and finance (BAF), business management (BBM), business studies (BBS), global supply chain management (BGSCM) and international business (BIB).

The business ethics course participants for this study include March 2019 semester (n= 497) using student as customer approach and August 2019 semester (n= 355) using employer as customer approach to teaching and learning.

Procedure

The data is collected using an adaptation of economics Nobel laureate, Banerjee’s (2019) randomised control trials (RCT). There was no need to randomise since both cohorts have a self interest to complete the semester examination. The ‘treatment’, employer as customer for August 2019 cohort was compared to the long standing practice of student as customer for March 2019 cohort. It is ethically not possible to divide the August or March cohort into two groups to compare the two approaches to avoid one subgroup obtaining superior results compared to the other.

The adapted RCT was suitable since all other aspects for the two cohorts could be controlled. First, both cohorts had similar demographics of Malaysian Chinese local students to other Malaysian local students to foreign students in the ratio 90 percent: 5 percent: 5 percent. Two thirds were female and one-third was male. Second, there were no changes in enrolment criteria since 2018. Third, all other aspects of teaching and learning were held constant including teaching hours, curriculum content, topics, number of examination questions, number of workshops and tutorials and their durations as well as similar tutors and lecturers. Fourth, all course objectives and content, assignments, examination questions and results were validated and approved by the same three levels of moderation namely internal university A peer moderation, degree awarding UK university moderation and UK university’s external examiner moderation. No ethics approval was needed as the employer as customer approach was approved by the degree awarding UK University. Fifth, both approaches used the same best practice teaching and learning expected by foreign awarding university. These include emphasis on developing critical thinking skills through logical thinking, problem solving based learning and decision making (Butler, 2012; Haplern, 2003; Liu et al., 2014); active learning strategies through collaborative learning and process oriented guided inquiry learning (Styers, 2018) that involves active participation in workshops, case based or problem based activities and using a small number of instructional methods (Todd et al., 2017); flipped classroom constructivist theory of learning where knowledge can be reconstructed from what students already know by making sense of new information (Gilboy et al.,2015); using cases that incorporate higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy including application, analysis and synthesis in diverse context; learning activities aligned with examinations and assessment criteria as provided in student course guide (Herrmann, 2013); obtaining actionable feedback through student satisfaction survey during learning cycles (Carless and Boud, 2018); providing students written feedback on assignments and using modern learning technologies (Laurillard, 2013) including blackboard consistent with students spending major portion of their time on digital platforms. Finally, there were no significant material changes in contextual conditions nor learning environment for university A in 2019 compared to 2018.

Measures

Both approaches used the hybrid learning model as in figure 1 (Nabi et al., 2017). The reproduction methods entail lectures, textbook chapter readings, related journal articles etc. Personalised participative methods include interactive searches for additional information related to tutorials and workshops and discipline related group assignments among others. Communication, discussion and production entail discussing workshop cases, tutorial concepts in small groups prior to related sessions and communicating through production slide presentation for example, online discussion forums set up in blackboard etc. This research uses level 2 post-program measure of final examination assessment of learning outcomes.

This paper uses the well developed learning outcomes of AACSB to compare both approaches using business ethics course examination assessments. The following AACSB learning outcomes (LO) were measured for both approaches :

1. Demonstrate knowledge of normative ethical theories (LO1)

2. Demonstrate ethical reasoning and decision-making skills (LO2)

3. Analyse the impact of normative ethical theories on relevant environment (LO3)

4. Understand the impact of internal and external environmental factors on business practice (LO4)

5. Communicate through clearly structured and organised written work with supporting references (LO5)

All learning outcome data for both approaches were made available by the respective lecturers to the researcher on condition of confidentiality and maintaining data privacy due to sensitivity of data. An informal interview was conducted with business ethics lecturers for both approaches and with a former long serving Head of department of Management who provided contextual background of all business programs. These interview inputs were documented and used to explain the results in the discussion section.

Data Analysis

For both approaches, the examination requires student to answer two out of four questions with 1 hour given to answer each question. Each of the 4 questions were awarded the same maximum 50 marks. Each question in turn has marks allocated according to the five learning outcomes and corresponding weightage. For example 50 marks for each question are distributed according to LO1 = 5, LO2 =10, LO3 = 10, LO4 = 20 and LO5 = 5. The proficiency level 1 to 5 for each LO held the following meaning : 1 = Very Poor, 2 = Poor, 3 = Average, 4 = Good and 5 = Excellent. An example is computed for one student who answers questions 2 and 4 as given in table 1 below.

Table 1.

Sample computation for one student to determine LO proficiency.

Table 1.

Sample computation for one student to determine LO proficiency.

| Learning outcome |

Marks for question 2 |

Marks for question 4 |

Average for each LO |

Converted to proficiency level (average/max marks)* 5 |

Proficiency level awarded |

| LO1 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

Good |

| LO2 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

3 |

Average |

| LO3 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

4 |

Good |

| LO4 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

3 |

Average |

| LO5 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

Poor |

Contextual Differences

The March 2019 (n= 497) student as customer approach entailed 10 weekly workshop scenarios focused on critical thinking debates around common problem based ethical issues including the positive and negative aspects of whistle-blowing, minimum wage, bribery, sweatshops etc. Model answers were provided at the end of the workshops. A revision lecture reviewed some of these workshop questions that were reused in the examination.

The August 2019 (n=355) employer as customer approach entailed 10 weekly workshops applying critical thinking on contemporary case study scenarios of ethical misconducts of global companies. These scenarios used different broad-based cases to cater for the diverse cohorts. It included role playing of key stakeholders by different groups of students during the workshops. The workshops imparts Rest’s (1986) ethical decision making process skills that considers in turn ethical sensitivity or awareness, ethical judgement and ethical motivation to understand ethical misconduct and propose alternative viable ethical decisions based on relevant normative ethical theories. Medeiros et al.’s (2017) meta analysis found that the various values and meta-ethical principles of prior research were similar to Rest’s (1986) process. The students applied the same decision making process in new cases in the examination without any prior revision classes.

Discussion

These findings will be discussed to answer the two research questions :

Has the marketisation of higher education led to nominal human capital development?

Can substantive human capital be developed in the new normal of marketisation of higher education?

Student as Customer

It is understandable that marketisation of higher education will result from increasing competition for enrolment. Higher education will accordingly strive to satisfy student customers learning experiences similar to business firms providing customers with satisfying products and services leading to sharing of experiences with potential future customers.

This study finds a similar comparison between university A student satisfaction survey (SSS) criteria with pioneering American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI) (Fornell et al., 1996) as summarised in table 2. University A SSS criteria includes student expectation of content of learning materials that stimulate learning, the perceived value of teaching delivery and aspects of it that were beneficial to student learning, overall customer satisfaction index, the overall SSS score and student complaints or praises in the form of positive and negative aspects of the subject,.

Table 2.

Comparison of university A student as customer satisfaction with American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI).

Table 2.

Comparison of university A student as customer satisfaction with American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI).

| Criteria for product and service satisfaction (Fornell et al., 1996) |

Equivalent Student satisfaction criteria of University A |

1. customer expectation : overall expectation; how well the product fits the customer’s personal

requirements; reliability, or how often things would go wrong |

Teaching quality of academics, their classroom delivery, quality of academic feedback and interpersonal relationships in classroom (Hill et al., 2003) |

2. perceived value : Overall quality experience; how well the product fit the customer’s

personal requirements; reliability or how often things have gone wrong; Rating of quality given price |

Assessing learning environment and learning gains or outcomes (SSS) that contribute to work readiness and personal development (AACSB)(Gunn, 2018). |

| 3. Customer Satisfaction Index : performance that falls short of or exceeds expectations; Performance versus the customer's ideal |

Overall student satisfaction survey score with minimum standard of 70% satisfaction for large student cohort and rising progressively for smaller cohorts*. |

| 4. customer complaint : Has the customer complained formally or informally about the product or service |

Formal SSS feedback is shared with lecturers to improve future student satisfaction on teaching and learning. |

| 5. customer loyalty : Repurchase likelihood, Price tolerance (increase or decrease) to induce repurchase |

Satisfied student customers will inform future potential student customers to enrol. |

This satisfaction of student customer also extends beyond the academe. Marketing, branding and student services leveraged higher education global rankings to guide student choice in developed nations (Brown and Carasso, 2013). However, Malaysia’s private higher education marketed and branded themselves as low cost eduction hub complete with student services that offered top ranked foreign university degrees. These private universities like university A were built with complete amenities including low-cost lodgings, sports and recreation facilities and access to entertainment, low cost food and affordable semi-furnished single room lodgings within walking distance of education hub.

However, despite higher education adopting similar customer satisfaction metrics, employers in recent years have expressed dissatisfaction with the human capital developed. University A recorded a significant single digit drop in employability in their 2018 graduating class. This anomaly can be traced to the existence of gaps in expectations of both student and employers as summarised in table 3. This anomaly can be addressed by emphasising learning outcomes as for employer as customer rather than emphasising student satisfaction survey score as for student as customer. Clearly, the AACSB learning outcomes correlates with employer expectations of human capital in key aspects (in italics) as identified by Donald et al., (2019).

Table 3.

Comparison between employer and student expectations with AACSB learning outcomes mapped to employer expectation.

Table 3.

Comparison between employer and student expectations with AACSB learning outcomes mapped to employer expectation.

| Employer expectations |

Student expectations |

AACSB Learning outcome |

Cognitive skills (Suleman, 2018)

Blooms taxonomy : understanding knowledge, analysis, synthesis, evaluation/critical thinking |

Passing tests (Voss et al., 2007) rather than acquisition of cognitive skills desired by employers |

Demonstrate knowledge of normative ethical theories (LO1)

Analyse the impact of normative ethical theories on relevant environment (LO3).(scholastic capital)

|

Technical discipline specific skills (Suleman, 2018)

Science, technology, engineering, business management etc |

Discipline specific knowledge from higher education and related experience from internships (Lisa et al., 2019) |

Demonstrate ethical reasoning and decision-making skills (LO2).

(market-value capital) |

Relational skills

Teamwork, interpersonal communication,

social and cultural skills (Singh et al., 2022) |

Assume developed as part of normal course through group assignments, presentations using multicultural team* |

Understand the impact of internal and external environmental factors on business practice (LO4). (social and cultural capital) |

Others

Initiative/ proactive, leadership, enterprising, organising (Singh et al., 2022)

engagement, willingness to take on extra work (Lisa et al., 2019) |

Leadership and authority (Lisa et al., 2019)

Passive learning (Herrmann, 2013) |

Communicate through clearly structured and organised written work with supporting references (LO5). (psychological capital) |

Table 4.

Overall comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches.

Table 4.

Overall comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches.

| Learning outcomes |

Proficiency level |

Mac 2019 (n=497) Percentage |

Aug 2019 (n=355) Percentage |

Employer as customer approach is … |

| LO1. Demonstrate knowledge of normative ethical theories |

Poor & very poor |

21 |

11 |

Superior |

| Good |

37 |

48 |

| LO2. Demonstrate ethical reasoning and decision-making skills |

Poor & very poor |

13 |

8 |

Superior |

| Good |

32 |

40 |

| LO3. Analyse the impact of normative ethical theories on relevant environment |

Poor & very poor |

12 |

9 |

Neutral |

| Good |

49 |

43 |

| LO4. Understand the impact of internal and external environmental factors on business practice |

Poor |

3 |

15 |

Inferior |

| Good |

57 |

47 |

| LO5. Communicate through clearly structured and organised written work with supporting references |

Poor |

19 |

5 |

Superior |

| Good |

36 |

42 |

University A’s approach to teaching and learning based on student as customer can clarify this mismatch in expectations. A top management representative speaking to lecturers of University A during an open-day enrolment in 2019 set the expectation as related by Lecturer E,

“ In University A, we handhold our students to acquire their degrees”

However, the leaning outcomes for student as customer approach does not support Hanushek (2016) consequent expectation of poor acquisition of cognitive skills. This counterfactual can be explained by the workshop questions that are meant to build cognitive skills in fact lead to passive learning as found by Herrmann (2013) since model answers are provided for workshops. The model answers supports Voss et al.(2007) finding of emphasising passing examination where revision class provides clues on possible examination questions reproduced from workshops.

In response to question on whether students actively engage in workshop discussions:

“The majority do not even read the questions since they are silent when asked questions”- Lecturer S (Mar2019 cohort)

In response to why examination scripts show virtually identical answers to questions both in sentence construction and in sequencing of paragraphs:

“Model answers are provided at the end of the workshops.”-Lecturer S (Mar2019 cohort)

Both these responses show nominal acquisition of cognitive and technical or conceptual skills as well as the lack of initiative to learn prior to workshop as expected of flip classrooms. This is understandable since only rote learning of model answers to questions that are reproduced in examination are required to pass examinations leading to false positive learning outcomes. Furthermore, provision of model answers enable lecturers to reduce frustration of students glamouring for ‘correct answers’ rather than engaging in discussions that lead to misconceptions on answers (Hermann, 2013). It also extends Tomlinson’s (2017) research on seeking popularity not through ‘dumping down’ but by revision classes which hint at possible workshop questions reproduced in examination. These findings support Slaughter et al. (2004) findings that marketisation of education lead to satisfying the student customers.

This nominal learning can be addressed by adopting employer as customer approach. In response to student request for model answers for workshop questions for Aug2019 cohort:

“ No need since workshops are developing your ethical decision making skills desired by employers which you will apply in new case questions in final examination. Furthermore, I do not want you to share answers with your juniors since I will be using the same questions in future workshops. ”- Lecturer E

This deep learning approach is conducive to altering preconceived answers, and learning from correct answers (Hermann, 2013). Based on researcher’s 2 decade extensive industry top management experience, it also prepares students for similar discussions in corporate world where ‘the correct answer’ is reached from initial misconceptions and correcting them from new related factual data. Furthermore, this deep learning should not be contingent primarily on whether students are satisfied with course quality or having the right personality or students are intrinsically motivated, feel self-confident and self-efficacious as advocated by Baeten et al. (2010). The main motivating factor for adoption of such deep learning should be communicated to students to develop human capital to enhance their ultimate goal of employability. The study show that even if some students do not have the right personality and motivations conducive to deep learning, they will learn. According to lecturer E,

“Overall learning outcomes were superior compared to student as customer approach and only a handful of failures were due to non-submission of assignment or non-attendance of examination”

Students come with varying knowledge base and abilities to learn, different personalities and motivations to learn (Baeten et al., 2010). Cognisant of these facts, this study included good feedback practices for formative assessment assignments and workshops as advocated by Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick (2006) to facilitate deep learning for employer as customer approach. These include facilitating students to develop self-assessment or reflection by providing individual specific precise high quality feedback information on key concepts and their appropriate applications; encouraging dialogue around learning at end of each lecture and during workshops; providing written feedback that promotes positive motivational beliefs and enhances self-esteem for assignments. In addition, lecturer E recommended the sharing of top graded assignments with others to close the gap between current and desired performance to accelerate learning and enhance skills conducive to employability. Learning outcome findings for both approaches will support these qualitative interview findings.

Learning Outcome LO1

Table 5 summarises the comparison by business programs between Aug2019 employer as customer and Mac2019 student as customer approaches to

demonstrate knowledge of normative ethical theories (LO1).

Both show overall good levels for LO1. However, the employer as customer approach is superior for all programs with the exception of Financial Analysis (BFA) and Accounting and Finance (BAF). The superior LO1 arises from case study workshops that build skills to demonstrate knowledge of normative ethical theories consistently in authentic contemporary real world case scenarios as recommended by Jackson and Bridgstock (2021). In contrast, student as customer approach workshops focus on debating generic ethical issues such as whistle-blowing, minimum wage, bribery, sweatshops.

Highly superior learning outcomes were achieved for three programs, Financial Economics (BFE), Business Studies (BBS) and Global Supply Chain Management (BGSCM). According to the former head of department (HOD),

“These programs tend to consider a broader range of stakeholders than the relatively narrower range considered for BMKT, BBM and BIB”

Considering broader range of stakeholders is consistent with good governance implicit in ethical theories as BFE does through macroeconomics and microeconomics; BBS does through suppliers and customers and BGSCM does through supply-chain players from sourcing raw material suppliers, manufacturing to delivering to customers all from diverse nations with often different laws and regulations.

Inferior results for employer as customer approach for BFA and BAF courses has two explanations. First, both focus on preparing financial reports based on production, sales and related transaction figures that are devoid of ethical context. Second, the absence of model answers and new case questions in examination makes this challenging for students more used to analysing figures than understanding wordy case studies.

Learning Outcome LO2

Table 6 summarises the comparison by business programs between Aug2019 employer as customer and Mac2019 student as customer approaches to

demonstrate ethical reasoning and decision-making (LO2).

Both show overall good levels for LO2. However, the employer as customer approach is superior for all programs with only Accounting and Finance (BAF) being inferior and Financial Economics (BFE) and Business studies (BBS) being neutral. The superior LO2 arises from case study workshops that build demonstrating ethical reasoning and decision-making skills consistent with Ramírez-Montoya (2021) postulate of applying critical thinking to real-world problem solving scenarios to generate superior learning outcomes. The student as customer approach is superior for BFA likely due to financial analysis course emphasising reasoning skills using clearly structured Rest’s (1986) decision making process as required for LO2.

Highly superior LO2 including exceptionally large number of excellent proficiency level was achieved for Global Supply Chain Management (BGSCM) which according to the former HOD,

“BGSCM considers a broader range of stakeholders than the narrower range considered for BMKT, BFA, BBM and BIB for decision making.”

Inferior results for employer as customer approach for BAF course is as explained for LO1.

Learning Outcome LO3

Table 7 summarises the comparison across business programs between Aug2019 employer as customer and Mac2019 student as customer approaches in analysing the

impact of normative ethical theories on relevant environment (LO3).

Both show overall good levels for LO3. However, the employer as customer approach is superior to the student as customer approach for all programs with only BAF being inferior and BMKT, BFA and BBM being neutral. The superior LO3 arises from case study workshops that consistently require analysing the impact of normative ethical theories on business environment for which both BBS and BIB consider relatively more stakeholders. As for highly superior programs, according to the former HOD,

“BFE has highly superior result since its students are taught to consider the impact of both micro and macro economic environments on business firms “

BGSCM highly superior result is as explained for LO2. Inferior results for employer as customer approach for BAF courses is due to these programs primarily focused on shareholder impact on bottomline.

Learning Outcome LO4

Table 8 summarises the comparison across business programs between Aug2019 employer as customer and Mac2019 student as customer approaches on the

impact of internal and external environment factors on firm business practices (LO4).

Employer as customer approach does poorly for LO4 though it is highly superior for BGSCM and BIB. According to the former HOD,

“BGSCM and BIB students are taught to consider the impact of internal and external environmental factors arising from managing supply-chain players in multiple jurisdictions and managing international businesses respectively.”

BMKT, BFA, BAF, BBM and BBS programs show inferior LO4 since students of these programs primarily consider impact of internal factors on achieving business goals. According to the former HOD,

“BMKT focusses on internal factors impacting revenue and profits. BFA and BAF focus on impact of firm financial transactions to minimise cost and maximise firm revenue. BBM focusses on impact of management of firm’s internal departments on shareholder goals. BBS focusses on impact of value adding by marketing, operations and other components of business on shareholder goals.”

Learning Outcome LO5

Table 9 summarises the comparison across business programs between Aug2019 employer as customer and Mac2019 student as customer approaches in

communicating through clearly structured and organised written work with supporting references (LO5).

Both show overall good levels for LO5. However, the employer as customer approach is superior for all programs with only BMKT and BBM being neutral. The main reason for superior LO5 is that the workshops consistently train the students to use Rest’s (1986) structured ethical decision making process to organise their written arguments supported by relevant normative ethical theories. The students are well trained to apply Rest’s (1986) approach in new case examination questions.

Summary Learning Outcomes

Table 4 provides the overall summary comparison between both approaches for all learning outcomes. The research empirically show that learning outcomes across business programs are superior overall for employer as customer approach compared to student as customer approach especially for LO1, LO2 and LO5. It is only inferior for LO4.

Table 10 provides a more detailed summary for all learning outcomes across programs supporting this overall conclusion.

Table 10.

Summary comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches for all LOs.

Table 10.

Summary comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches for all LOs.

| Program |

Employer as customer approach for LO1 is … |

Employer as customer approach for LO2 is … |

Employer as customer approach for LO3 is … |

Employer as customer approach for LO4 is … |

Employer as customer approach for LO5 is … |

|

| BMKT (Marketing) |

Superior |

Moderately Superior |

Neutral |

Inferior |

Inferior |

|

| BFA (Financial analysis) |

Inferior |

Superior |

Neutral |

Inferior |

Superior |

|

| BFE (Financial economics) |

Highly Superior |

Neutral |

Highly Superior |

Neutral |

Highly Superior |

|

| BAF (Accounting and finance) |

Moderately Inferior |

Inferior |

Inferior |

Inferior |

Moderately Superior |

|

| BBM (Business management) |

Superior |

Superior |

Neutral |

Inferior |

Neutral |

|

| BBS (Business studies) |

Highly Superior |

Highly superior |

Superior |

Inferior |

Superior |

|

| BGSCM (Supply chain management) |

Highly Superior |

Highly superior |

Highly Superior |

Highly superior |

Highly Superior |

|

| BIB (International business) |

Superior |

Superior |

Superior |

Highly Superior |

Superior |

|

The overall superior learning outcome for employer as customer approach is based on problem based learning (PBL) which is conducive to deep learning with students intrinsically motivated to understand what is being taught through solving real-world business problems (Dolmans et al., 2016).

However, employer as customer approach for Business ethics course show poor learning outcomes for some programs due to inherent limitations of these programs. For BFA and BAF to benefit from employer as customer approach there is a need to incorporate ethical considerations consistent with environment, social and governance requirements in financial reporting that considers other stakeholders beside shareholders as advocated by the Security and Exchange Commission for public listed firms (Park et al., 2014). BMKT, BFA, BAF, BBM and BBS programs which show inferior LO4 for employer as customer approach, they should consider incorporating not only the impact of internal factors on achieving business goals but also external factors in their programs. This approach is consistent with business schools introducing strategy management course.

Has the marketisation of higher education led to nominal human capital development? It is clear from the discussion of the findings that marketisation of higher education will lead to the adoption of student as customer approach to teaching and learning that will result in nominal human capital development. This is consistent with memorising and regurgitating model answers to questions hinted on during revision class in the examination.

Can substantive human capital be developed in the new normal of marketisation of higher education? Discussion of findings show that overall, adopting employer as customer approach leads to superior learning outcomes desired by employers even in an era of marketisation of education. Its systematic adoption for all business courses has implications to higher education approach to teaching and learning as discussed below.

Robust Quality Assurance

The existing quality assurance process with multiple levels of moderation including independent external moderation as adopted by university A appears robust and consistent with best practices of degree awarding UK university. However, this research found possible deterioration of quality assurance using student as customer approach that supports Altbach et al. (2019). The robust quality assurance of foreign awarding university is stymied by university A lecturers choosing 10% of sample marked examination scripts for moderation. This will be in proportion to top 10%, middle 10% and bottom 10% with lecturer choosing the scripts with possible bias in selection choice to avoid choosing scripts with similar model answers for student as customer approach.

The process can be improved to ensure robust quality assurance by adopting the following. First, whilst pursuing best practice teaching and learning, discourage the use of model answers. Students should engage in active learning use active learning strategies that leverage collaborative learning and process oriented guided inquiry learning (Styers, 2018) which entail listening, interactive collaborative discussion and taking notes as was employed in employer as customer approach. Second, moderation samples should be selected at random by foreign degree awarding university from list of student examination scripts to overcome possible selection bias by host university.

Lecturer Professionalism and Substantive Human Capital Development

In the era of marketisation of higher education, students as customers expect satisfying stress-free teaching and learning experiences. This expectation will lead lecturers to guide students to pass examinations as found in this study for student as customer approach.

Employer as customer approach can restore lecturer professionalism and substantive human capital development by focusing on academic integrity of imparting learning outcomes desired by employers. First, SSS score for performance assessment of lecturers should be replaced by assessment of learning outcomes. Second, the course guide should emphasise learning outcomes and clear assessment rubrics based on learning outcomes without the need to provide model answers to encourage deep learning. Whilst university A does so, it however prioritises student as customer approach which induces lecturers to provide workshop model answers for possible examination questions leading to another source of surface learning beyond that found by Dolmans et al. (2016). University A does mitigate high workload and assessments that will lead to surface learning (Dolmans et al., 2016) according to lecturer E,

“All lecturers for each semester are required to submit high weightage assignment deadlines to a central body that recommends revisions to deadlines to minimise bunching of submissions towards end of semester”

Third, workshops should consistently focus on developing cognitive skills desired by employers as per learning outcomes (Suleman, 2018). The examination questions should also include new contemporary world case scenarios consistent with Ramírez-Montoya (2021) postulate of applying critical thinking to real-world problem solving scenarios to generate superior learning outcomes. Workshops also develop relational skills through complex collaborative problem-solving, inquiry-based learning using real world authentic contexts as recommended by Jackson and Bridgstock (2021). Consequently it should not lead to vocation driven education system that emphasise employability over knowledge acquisition, a concern raised by Cheng et al. (2022) since knowledge acquisition is translated into skills desired by employers.

Finally, revision classes should be discontinued provided it is made clear to students that examination questions are based on learning outcomes as provided in course guide.

These recommendations can address the current mismatch between graduate competences and employer human capital needs as found by Ebelha et al. (2020) and in this research where employability levels decreased in 2019 despite adopting best practice teaching and learning.

This approach is consistent with Arrow (1961) who showed that increase in per capita income cannot be fully explained by capital to labour ratio unless one includes technological change that comes from learning by doing or active learning which grows with time the more one engages in solving problems as practiced in workshops (Herrmann, 2013). This view is also consistent with findings that employer as customer approach is closer to the paradigm of results maximisation that has been successfully practiced by major Japanese higher education in comparison to potential maximisation practiced by Australian higher education (Saito and Parm, 2021). It is not surprising that the Japanese economy is vastly superior to the Australian economy consistent with finding that differences in acquisition of cognitive skills primarily explain the differences in economic growth rates among nations (Hanushek, 2016).

Human Capital Development Survey

This research found that the current student satisfaction survey (SSS) as adopted by university A will lead to similar concerns found by other researchers. First, poor acquisition of cognitive skills that support Hanushek (2016) arising from workshop model answers made available for possible examination questions. Second, fulfilling student expectation of passing tests that support Voss et al., (2007). Students are given hints on possible workshop questions that will reappear in final examination during revision class. Third, damage to teaching and learning pedagogy as found by Nixon et al., (2018). When students know they will be provided model answers to workshopquestions they will be less inclined to actively participate in learning process as found in this study. Fourth, passive learning that support Herrmann, (2013). Students are less engaging and less prepared despite adopting flip classroom approach where workshop information is uploaded on blackboard one week ahead as found in this study. According to lecturer S, for student as customer approach,

“During workshops, they know they will be provided model answers at the end of the workshop. Many come unprepared and show blank stares when asked guided questions”

Clearly, Medeiros et al.’s, (2017) suggestions to enhance active class participation does not work for student as customer approach since they know that model answers will be provided.

Finally, once rigorous lecturers transform into popular lecturers to maintain employment as found by Tomlinson, (2017). According to lecturer E for employer as customer, who observed his colleague lecturer S for student as customer guiding them to submit high grade scoring assignments,

“I observed long line of students throughout the day over one week before assignment deadline waiting for their turn to meet Mr S on guidance for draft assignment before submission”

According to lecturer E this impacted his SSS score compared to Mr S,

“ I only obtained 54% score despite using the last 15 min during my lecture and workshop over the normal weekly 2 hour consultation time to clarify common assignment queries with all students whilst Mr S obtained more than 70%. My HOD was very concerned but on seeing that my learning outcomes were superior to my colleague Mr S, he made an exception and allowed me to renew my contract.”

Despite achieving overall superior learning outcomes, employer as customer approach much lower overall SSS score does not support Burgess et al.’s, (2018) assertion that the best predictors of student satisfaction were ‘teaching quality’ and ‘organisation & management’. In contrast, students satisfaction primarily comes from provision of model answers for workshop questions and revision class that hints of possible workshop questions appearing in final examination as in the case of student as customer approach.

In contrast to claims of objective assessment with SSS score linked to career development and remuneration (Gunn, 2018; Kallio et al., 2016), this research found that the system is gamed since SSS assumes a significant weightage in university A in comparison to research and administration. It comes as no surprise that many scholars find student satisfaction metrics such as SSS not measuring teaching excellence as also found in this study for student as customer approach (Crawford and Spence, 2019; Griffioen et al., 2018; Kalfa et al., 2018; Kallio et al., 2016 ). This paper’s findings show that high teaching excellence scores in fact indicate nominal teaching and learning in the case of student as customer approach.

Consequently, these concerns can be ameliorated by renaming SSS to Human capital development survey which emphasises using student feedback to improve lecturer teaching and learning as recommended by Lea et al. (2003). Communication is critical to ensure that enrolment does not suffer in the short term. With expected increase in employment in the medium to long term, enrolment should revert to normal. Lecturers performance on teaching and learning component will alternatively be based on achieving desired level of learning outcomes.

This paradigm shift is logical. Ultimately it is the substantive learning of especially cognitive skills desired by employers (Suleman, 2018) that will bridge the competence gap identified by employers (Ebelha et al., 2020) critically needed for maintaining competitive advantage in the local, regional and global market place.

Limitation of Research

Although the empirical findings are limited to only one course, they can possibly be extended to all business programs in university A that adopts the student as customer approach to teaching and learning. Similarly, whilst the findings are limited to one university, it can possibly be extended to all other higher education in that education hub that awards UK degrees and that adopt similar student as customer approach as university A.

Future Research

The study should be replicated using RCT methodology first on a pilot level for one course, then progressively for other courses within the program before adopting employer as customer approach.

Research on post-employment longitudinal study involving employer feedback and graduate feedback on career development, duration of employment, career progression will clarify the extent of the efficacy of both approaches to employability and critically in meeting competence requirements of employers.

The proposed revamping of SSS to Human Capital development survey should be researched on a pilot level to determine the extent it satisfy students in relation to enhancing their teaching and learning before it is rolled out throughout all programs. This could entail mixed methods approach of surveys and interviews of students and their lecturers at the end of the academic year.

Research should also consider the effect on lecturers professionalism of adopting employer as customer approach in the context of of rollout of human capital development survey.

Conclusions

The marketisation of higher education can lead to nominal human capital development, an undesirable race to the bottom. However, substantive human capital can be developed in the new normal of marketisation of higher education by adopting employer as customer approach to teaching and learning.

Low cost higher education hub in developing nations provides a win-win proposition for developed nation and developing nation universities provided they adopt employer as customer approach to teaching and learning that builds substantial human capital desired by employers for firm competitiveness and for nations economic development.

It is logical for higher education to focus on enrolment in a highly competitive environment for students. Using the employer as customer approach to teaching and learning will enable students to take career ownership to be employed in the careers they aspire as advocated by Donald et al. (2019). The renaming of student satisfaction survey to human capital development survey may lead to some reduction in enrolment in the short term but in the medium to long term with increasing employability and career progression of its graduates, enrolment should return to normal high levels.

References

- Abelha, M.; Fernandes, S.; Mesquita, D.; Seabra, F.; Ferreira-Oliveira, A.T. Graduate employability and competence development in higher education—A systematic literature review using PRISMA. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altbach, P.G.; Reisberg, L.; Rumbley, L.E. Trends in global higher education: Tracking an academic revolution. Brill, 2019.

- Arrow, K.J. The economic implications of learning by doing. In Readings in the Theory of Growth; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1961; pp. 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Baeten, M.; Kyndt, E.; Struyven, K.; Dochy, F. Using student-centred learning environments to stimulate deep approaches to learning: Factors encouraging or discouraging their effectiveness. Educ. Res. Rev. 2010, 5, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, A.P.; Millward, L.J. Differentiating knowledge in teams: The effect of shared declarative and procedural knowledge on team performance. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2007, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barneejee, A. Field Experiments and the Practice of Economics. Nobel Prize Lecture. 8 December 2019.

- Bloom, D.E.; Canning, D.; Chan, K. Higher education and economic development in Africa (Vol. 102); World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.; Carasso, H. Everything for sale? The marketisation of UK higher education. Routledge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bunce, L.; Baird, A.; Jones, S.E. The student-as-consumer approach in higher education and its effects on academic performance. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 1958–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.; Senior, C.; Moores, E. A 10-year case study on the changing determinants of university student satisfaction in the UK. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, H.A. Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment predicts real-world outcomes of critical thinking. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2012, 25, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D.; Boud, D. The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Adekola, O.; Albia, J.; Cai, S. Employability in higher education: A review of key stakeholders' perspectives. High. Educ. Eval. Dev. 2022, 16, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'abate, C.P.; Youndt, M.A.; Wenzel, K.E. Making the most of an internship: An empirical study of internship satisfaction. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2009, 8, 527–539. [Google Scholar]

- Dolmans, D.H.; Loyens, S.M.; Marcq, H.; Gijbels, D. Deep and surface learning in problem-based learning: A review of the literature. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2016, 21, 1087–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, W.E.; Baruch, Y.; Ashleigh, M. The undergraduate self-perception of employability: Human capital, careers advice, and career ownership. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Johnson, M.D.; Anderson, E.W.; Cha, J.; Bryant, B.E. The American customer satisfaction index: Nature, purpose, and findings. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboy, M.B.; Heinerichs, S.; Pazzaglia, G. Enhancing student engagement using the flipped classroom. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grapragasem, S.; Krishnan, A.; Mansor, A.N. Current Trends in Malaysian Higher Education and the Effect on Education Policy and Practice: An Overview. Int. J. High. Educ. 2014, 3, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffioen, D.M.E.; Doppenberg, J.J.; Oostdam, R.J. Are more able students in higher education less easy to satisfy? High. Educ. 2018, 75, 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T.; Fuß, S.; Voss, R.; Gläser-Zikuda, M. Examining student satisfaction with higher education services: Using a new measurement tool. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2010, 23, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, A. Metrics and methodologies for measuring teaching quality in higher education: Developing the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF). Educ. Rev. 2018, 70, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, E.A. Will more higher education improve economic growth? Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2016, 32, 538–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, D.F. Thought and knowledge: An introduction to critical thinking; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, K.J. The impact of cooperative learning on student engagement: Results from an intervention. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2013, 14, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Y.; Lomas, L.; MacGregor, J. Students’ perceptions of quality in higher education. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2003, 11, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Bridgstock, R. What actually works to enhance graduate employability? The relative value of curricular, co-curricular, and extra-curricular learning and paid work. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, K.M.; Kallio, T.J.; Tienari, J.; Hyvönen, T. Ethos at stake: Performance management and academic work in universities. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 685–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. Student mobility and internationalization: Trends and tribulations. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2012, 7, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurillard, D. Rethinking university teaching: A conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies. Routledge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lažetić, P. Students and university websites—Consumers of corporate brands or novices in the academic community? ” Higher Education 2013 2019, 77, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, S.J.; Stephenson, D.; Troy, J. Higher education students' attitudes to student-centred learning: beyond’ educational bulimia'? . Studies in higher education 2003, 28, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, L.L.; Brinkman, P.T. The Economic Value of Higher Education; American Council on Education/Macmillan Series on Higher Education; Macmillan Publishing, 866 Third Avenue: New York, NY, USA, 1988; p. 10022. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.C. The role of higher education in economic development: An empirical study of Taiwan case. J. Asian Econ. 2004, 15, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, O.L.; Frankel, L.; Roohr, K.C. 2014. Assessing critical thinking in higher education: Current state and directions for next-generation assessment. ETS Research Report Series, 2014; 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lisá, E.; Hennelová, K.; Newman, D. Comparison between Employers' and Students' Expectations in Respect of Employability Skills of University Graduates. Int. J. Work-Integr. Learn. 2019, 20, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Malouff, J.M.; Hall, L.; Schutte, S.N.; Rooke, E.S. Use of motivational teaching techniques and psychology student satisfaction. Psychol. Learn. Teach. 2010, 9, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, K.E.; Watts, L.L.; Mulhearn, T.J.; Steele, L.M.; Mumford, M.D.; Connelly, S. What is working, what is not, and what we need to know: A meta-analytic review of business ethics instruction. J. Acad. Ethics 2017, 15, 245–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A.; Krueger, N.; Walmsley, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2017, 16, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, D.J.; Macfarlane-Dick, D. Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Stud. High. Educ. 2006, 31, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, E.; Scullion, R.; Hearn, R. Her majesty the student: Marketised higher education and the narcissistic (dis) satisfactions of the student-consumer. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 927–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nortvig, A.M.; Petersen, A.K.; Balle, S.H. A literature review of the factors influencing e-learning and blended learning in relation to learning outcome, student satisfaction and engagement. Electronic Journal of E-learning 2018, 16, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, C. Corporate social responsibilities, consumer trust and corporate reputation: South Korean consumers' perspectives. Journal of Business Research 2014, 67, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, L.W. Studying college access and choice: A proposed conceptual model. Higher education: Handbook of theory and research 2006, 99-157.

- Ramírez-Montoya, M.S.; Loaiza-Aguirre, M.I.; Zúñiga-Ojeda, A.; Portuguez-Castro, M. Characterization of the Teaching Profile within the Framework of Education 4.0. Future Internet 2021, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rest, J.R. Moral development: Advances in research and theory; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, S.J.; Dang, C.T. Are the ‘customers’ of business ethics courses satisfied? An examination of one source of business ethics education legitimacy. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 947–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, E.; Pham, T. A comparative institutional analysis on strategies deployed by Australian and Japanese universities to prepare students for employment. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2021, 40, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanahuja Vélez, G.; Ribes Giner, G. Effects of business internships on students, employers, and higher education institutions: A systematic review. J. Employ. Couns. 2015, 52, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, P.; Stevenson, K.; King, M.; Coates, D. University students' expectations of teaching. Stud. High. Educ. 2000, 25, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Dubey, R.; Paul, J.; Tewari, V. The soft skills gap: A bottleneck in the talent supply in emerging economies. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2022, 33, 2630–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, S.; Slaughter, S.A.; Rhoades, G. Academic capitalism and the new economy: Markets, state, and higher education. Jhu press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Solow, M.R. (1987). Growth Theory and After. 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Spooren, P.; Mortelmans, D.; Denekens, J. Student evaluation of teaching quality in higher education: Development of an instrument based on 10 Likert-scales. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2007, 32, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styers, M.L.; Van Zandt, P.A.; Hayden, K.L. Active learning in flipped life science courses promotes development of critical thinking skills. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2018, 17, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suleman, F. The employability skills of higher education graduates: Insights into conceptual frameworks and methodological options. High. Educ. 2018, 76, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M. Student perceptions of themselves as 'consumers’ of higher education. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2017, 38, 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, R.; Gruber, T.; Szmigin, I. Service quality in higher education: The role of student expectations. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willetts, David. Robbins Revisited: Bigger and Better Higher Education; Social Market Foundation: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. Transaction cost economics: The natural Progression. Prize Lecture to the memory of Alfred Nobel, 8 December 2009.

- Winstone, N.E.; Boud, D. The need to disentangle assessment and feedback in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 5.

Comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches by program for LO1 :Demonstrate knowledge of normative ethical theories.

Table 5.

Comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches by program for LO1 :Demonstrate knowledge of normative ethical theories.

| Program |

Proficiency level LO1 |

Mac 2019 (n=497) Percentage |

Aug 2019 (n=355) Percentage |

Employer as customer approach is … |

| BMKT (Marketing) |

Poor |

27 |

6 |

Superior |

| Good |

18 |

82 |

| BFA (Financial analysis) |

Poor |

23 |

33 |

Inferior |

| Good |

50 |

33 |

| BFE (Financial economics) |

Poor |

50 |

0 |

Highly Superior |

| Good |

50 |

80 |

| BAF (Accounting and finance) |

Poor |

11 |

14 |

Moderately Inferior |

| Good |

48 |

45 |

| BBM (Business management) |

Poor |

29 |

8 |

Superior |

| Good |

24 |

34 |

| BBS (Business studies) |

Poor |

25 |

0 |

Highly Superior |

| Good |

6 |

33 |

| BGSCM (Supply chain management) |

Poor |

33 |

0 |

Highly Superior |

| Good |

22 |

96 |

| BIB (International business) |

Poor |

65 |

14 |

Superior |

| Good |

12 |

38 |

Table 6.

Comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches by program for LO2 : Demonstrate ethical reasoning and decision-making skills.

Table 6.

Comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches by program for LO2 : Demonstrate ethical reasoning and decision-making skills.

| Program |

Proficiency level LO2 |

Mac 2019 (n=497) Percentage |

Aug 2019 (n=355) Percentage |

Employer as customer approach is … |

| BMKT (Marketing) |

Poor |

7 |

0 |

Moderately Superior |

| Good |

29 |

32 |

| BFA (Financial analysis) |

Poor & very poor |

20 |

0 |

Superior |

| Good |

27 |

50 |

| BFE (Financial economics) |

Poor |

0 |

30 |

Neutral |

| Good |

0 |

50 |

| BAF (Accounting and finance) |

Poor |

4 |

9 |

Inferior |

| Good |

43 |

31 |

| BBM (Business management) |

Poor |

39 |

10 |

Superior |

| Good |

27 |

44 |

| BBS (Business studies) |

Poor |

0 |

17 |

Neutral |

| Good |

6 |

60 |

| BGSCM (Supply chain management) |

Poor |

19 |

0 |

Highly superior |

| Excellent |

0 |

91 |

| BIB (International business) |

Poor |

35 |

3 |

Superior |

| Good |

0 |

10 |

Table 7.

Comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches by program for LO3 : Analyse the impact of normative ethical theories on relevant environment.

Table 7.

Comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches by program for LO3 : Analyse the impact of normative ethical theories on relevant environment.

| Program |

Proficiency level LO3 |

Mac 2019 (n=497) Percentage |

Aug 2019 (n=355) Percentage |

Employer as customer approach is … |

| BMKT (Marketing) |

Poor |

2 |

3 |

Neutral |

| Good |

64 |

68 |

| BFA (Financial analysis) |

Poor |

17 |

33 |

Neutral |

| Good |

13 |

33 |

| BFE (Financial economics) |

Poor |

0 |

0 |

Highly Superior |

| Good |

10 |

90 |

| BAF (Accounting and finance) |

Poor |

4 |

6 |

Inferior |

| Good |

59 |

34 |

| BBM (Business management) |

Poor |

26 |

8 |

Neutral |

| Good |

47 |

42 |

| BBS (Business studies) |

Poor |

19 |

0 |

Superior |

| Good |

28 |

60 |

| BGSCM (Supply chain management) |

Poor |

33 |

0 |

Highly Superior |

| Good |

33 |

61 |

| BIB (International business) |

Poor |

53 |

34 |

Superior |

| Good |

0 |

21 |

Table 8.

Comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches by program for LO4 : Understand the impact of internal and external environmental factors on business practice.

Table 8.

Comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches by program for LO4 : Understand the impact of internal and external environmental factors on business practice.

| Program |

Proficiency level LO4 |

Mac 2019 (n=497) Percentage |

Aug 2019 (n=355) Percentage |

Employer as customer approach is … |

| BMKT (Marketing) |

Poor |

13 |

18 |

Inferior |

| Good |

49 |

32 |

| BFA (Financial analysis) |

Poor |

0 |

33 |

Inferior |

| Good |

47 |

33 |

| BFE (Financial economics) |

Poor |

0 |

10 |

Neutral |

| Good |

60 |

80 |

| BAF (Accounting and finance) |

Poor |

0 |

8 |

Inferior |

| Good |

70 |

57 |

| BBM (Business management) |

Poor |

8 |

39 |

Inferior |

| Good |

27 |

19 |

| BBS (Business studies) |

Poor |

0 |

7 |

Inferior |

| Good |

69 |

17 |

| BGSCM (Supply chain management) |

Poor |

0 |

0 |

Highly superior |

| Good |

37 |

96 |

| BIB (International business) |

Poor |

29 |

0 |

Highly Superior |

| Good |

0 |

72 |

Table 9.

Comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches for LO5 : Communicate through clearly structured and organised written work with supporting references.

Table 9.

Comparison between employer as customer (Aug 2019) and student as customer (Mac 2019) approaches for LO5 : Communicate through clearly structured and organised written work with supporting references.

| Program |

Proficiency level LO5 |

Mac 2019 (n=497) Percentage |

Aug 2019 (n=355) Percentage |

Employer as customer approach is … |

| BMKT (Marketing) |

Poor |

11 |

3 |

Neutral |

| Good |

62 |

32 |

| BFA (Financial analysis) |

Poor |

47 |

0 |

Superior |

| Good |

10 |

17 |

| BFE (Financial economics) |

Poor |

40 |

0 |

Highly Superior |

| Good |

0 |

40 |

| BAF (Accounting and finance) |

Poor |

0 |

0 |

Moderately Superior |

| Good |

46 |

58 |

| BBM (Business management) |

Poor |

27 |

6 |

Neutral |

| Good |

24 |

19 |

| BBS (Business studies) |

Poor |

13 |

0 |

Superior |

| Good |

13 |

33 |

| BGSCM (Supply chain management) |

Poor |

48 |

4 |

Highly Superior |

| Good |

22 |

74 |

| BIB (International business) |

Poor |

12 |

0 |

Superior |

| Good |

0 |

31 |

|