1. Introduction

A key pillar in advancing human health is the medical workforce [

1]. In Saudi Arabia, the central structure of the healthcare system is based upon free healthcare services from publicly-owned facilities and government-employed healthcare providers [

2]. Subsequently, healthcare providers are a cornerstone of the healthcare system. Moreover, studies conducted on the Saudi population have uncovered a significant annual population growth rate ranging from approximately 3% to 3.5% in 1994 [

3,

4]. However, recent data indicates a further increase in the growth rate to 4.5% [

5], accompanied by a total fertility rate of 7.1% [

4]. These findings, coupled with previous research that established chronic neurologic disorders as the most prevalent type of disorders among the pediatric population [

6], underscore the utmost importance of comprehending the landscape of pediatric neurology and its workforce.The child neurology field underwent great transformation in the past few years and it continues to grow and expand across various aspects. The expansion of residency programs and the establishment of new traning centers throughout the country have contributed to the growing number of pediatric neurologists entering the workforce. However, this growth also brings about a range of issues and challenges that necessitate a thorough and rational assessment. Natural questions to ask are whether the workforce is equipped to handle these challenges. One key challenge is the current number of pediatric neurologists and the future need. The only available national studies which were published in 2005 and 2017 concluded that the total number of pediatric neurologists per 100,000 children remains way less than the standardized international ratio (0.4:100,000) with even shortage in some regions despite significant improvement as observed by the recent study [

7,

8]. Ever since the literature witnessed a scarcity in updates on the reality of the Saudi pediatric neurology workforce. On the other hand and as the workforce expands, more challenges arise, such as the occurrence of delays in the employment of recently trained pediatric neurologists. This study aims to investigate and analyze the current characteristics of the workforce, with a specific focus on their employment status and related data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

A community-based exploratory study was conducted on May 2023 in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional research [

9]. The study included pediatric neurology residents and graduates across the 13 region in Saudi Arabia. Residents and graduates were identified through national databases (i.e. Saudi Pediatric Neurology Society). Participants were enrolled using an electronic, self-administered questionnaire using Google Form which was distributed using WhatsApp application and email services. Pediatric neurology consultants and specialist were excluded from the study.

2.2. Survey design and validation

A 26-item questionnaire created according to the study objectives with few items adopted from similar literature [

8] was utilized in this study. The questionnaire consisted of four sections. The first section included a consent statement whereby the study participants’ acknowledged that their information would be utilized for research purposes and confirmed to be within the targeted population. The second section identified the participants’ personal data that include their age, gender, nationality, social status, residency program location, medical school location, type of the current training center (i.e. government hospital, academic institution, private hospital), current year of residency, number of research publications, monthly income, and their health insurance status. The third section was for current fellowship trainee. This include the type of current fellowship training, the training location.

Section 4 included questions to assess their post-graduation status by asking participants the timeframe needed to enroll into the workforce, the city of their first job, the average number of patients per clinic, type of available supporting services (i.e. epilepsy/EEG, clinical neurophysiology, neuromuscular/EMG, neurodevelopmental disabilities, sleep medicine, neurooncology, headache medicine, neurogenetics), if they have an academic job (i.e. lecturer, professor, etc..), if they have a research job (i.e. researcher, scientist, etc..), and finally their current job title.

2.3. Data analysis

Microsoft Excel version 20 sheet was used to store collected data. Statistical analyses were conducted using Rstudio (version 4.0.2). Categorical variables were described in frequency tables, and continuous variables were described with mean and standard deviation (SD) values. To assess whether participants in different employment groups differed on demographic characteristics and variables of analytical interest, preliminary analyses were first conducted. Continuous variables were first assessed on the normality of their distribution using Shapiro Wilk test. If the normality assumption was met, a parametric two-sample t-test would be conducted. If the normality assumption was not met, Mann-Whitney U-test would be used. Categorical variables were compared between the two employment groups using Fisher’s exact test given the subsample of data was too small to conduct a Pearson’s Chi-squared test [

10]. The significance of the effects of interest was estimated at a 95% confidence interval.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

Descriptive summary of demographic characteristics is shown in

Table 1. A total of 82 pediatric neurologists in Saudi Arabia responded to the survey. The response rate was 55.03%.

All participants enrolled in the study were deemed eligible by confirming that they were within the targeted population. Of the participants, 46% were males and 54% were females. Nearly all participants (99%) were Saudi nationals, and only one (1%) was an Egyptian national. The majority of participants were aged 32 years (n=12), the mean age was 33.24±5.66 years, and the age range was 25-62 years. As for participants’ relationship status, around 68% were married, 29% were singles, and 2% were engaged.

The majority of participants (48%) were currently pursuing postgraduate studies, and nearly 20% were fresh graduates. The rest of the participants varied in their current training levels, whereby most (14.63%) are currently R3 trainees. The majority (49%) of participants received a salary of >15,000 SAR, the rest fell between 12,000-15,000 (2%) and <1000 SAR (2%), and 35% did not answer. More than half of the participants (63%) did not receive health insurance.

3.2. Education, Research and Training

Descriptive summary of participants’ education, research and training is shown in

Table 2. Nearly all participants (98%) did their residency in Saudi Arabia, and only two participants did their residency abroad. Around 35% of participants did their residency at King Fahad Medical City (KFMC); 17% at King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Center (KFSHRC) in Riyadh; and nearly 15% at Prince Sultan Military Medical City (PSMMC).

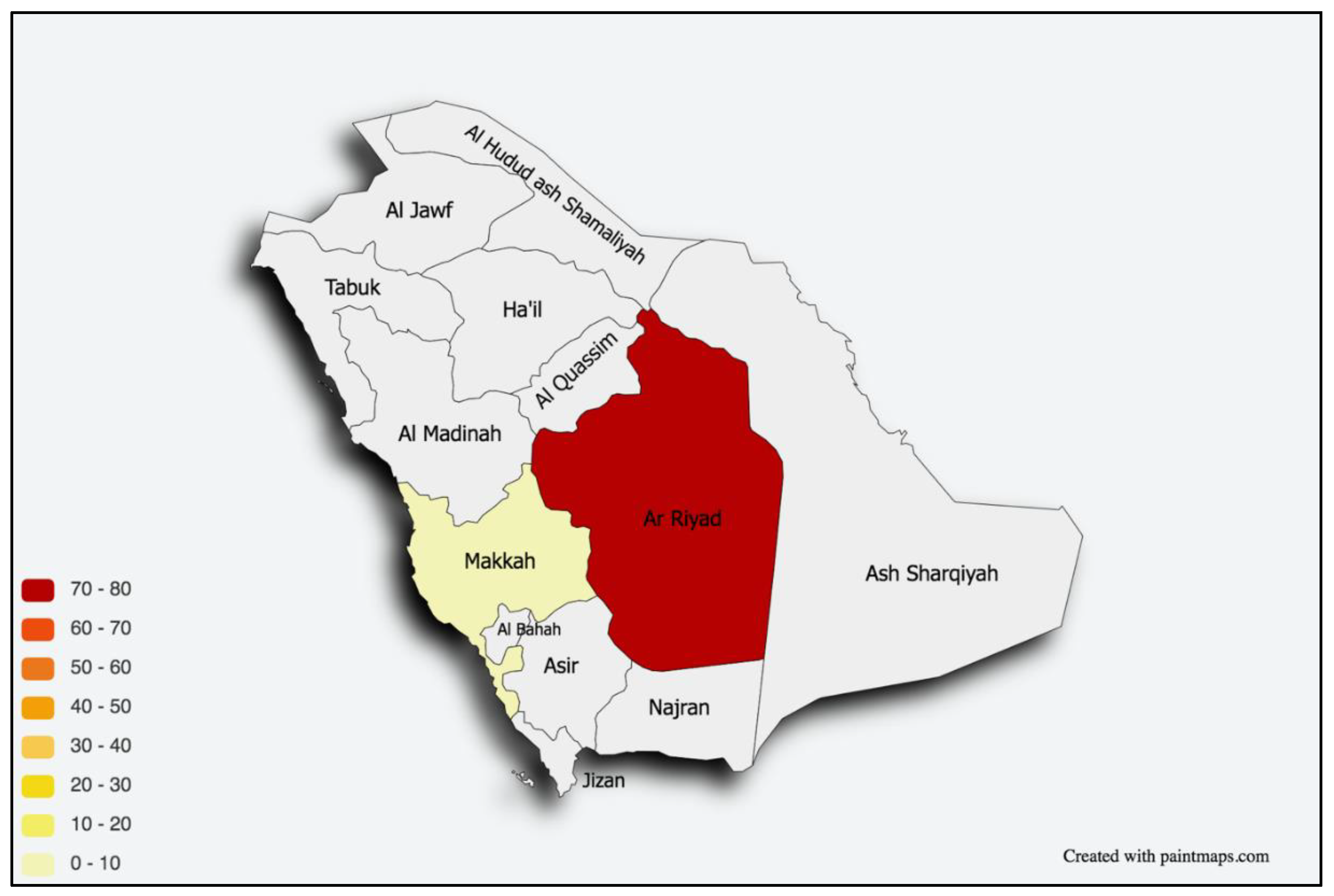

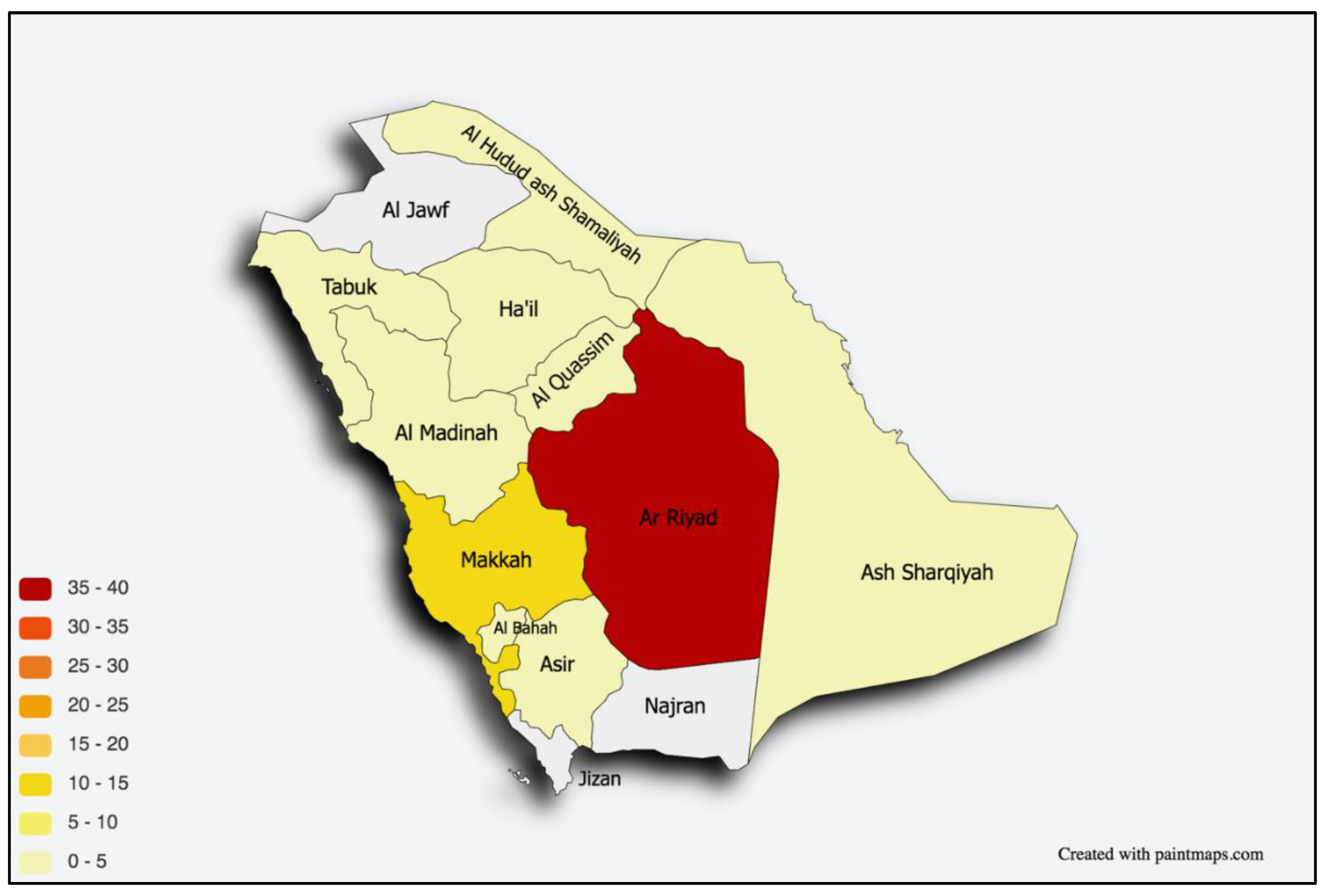

Figure 1 illustrates participants’ location of current practice by state based on their residency center, whereby most participants were clustered in Riyadh. Most participants (54%) started their residency between 2014 and 2018, and most (54%) graduated between 2019 and 2023. As for participants’ undergraduate education, 17% studied at King Abdulaziz University (KAU); around 16% studied at King Saud University (KSU); and nearly 11% studied at King Khalid University (KKU). Most participants had one (23%), two (21%) or three (20%) research publications (

Figure 2). Only 5% published more than 10 papers. Around 29% of participants are currently enrolled on a fellowship programme, mostly in Saudi Arabia (13%) or Canada (13%) and most (16%) are training in Epilepsy/EEG.

3.3. Employment Status

Descriptive summary of participants’ employment status is shown in

Table 3. The majority of participants who received their first job in the same city they were born in were in Riyadh (18%); 5% who were born in Jeddah also received their first job there; 5% who were born in Alhassa also received their first job there; 4% who were born in Abha also received their first job there; 4% who were born in Al-Madinah also received their first job there; 4% who were born in Makkah also received their first job there; only 1% who were born in Arar also received their first job there; 1% who were born in Hail also received their first job there; 1% who were born in Tabuk also received their first job there; and 1% who were born in Al-Qassim also received their first job there.

More generally and regardless of participants’ city of birth, nearly half of participants (49%) received their first job in Riyadh, and nearly 10% received their first job in Jeddah. As for participants’ location according to their first job, most participants were clustered in Riyadh, followed by Makkah. The majority of participants (46%) received their first job within 1-3 months from graduation; around 21% received their first job after 4-6 months from graduation. Only around 3% waited 6-10 years before their first job.

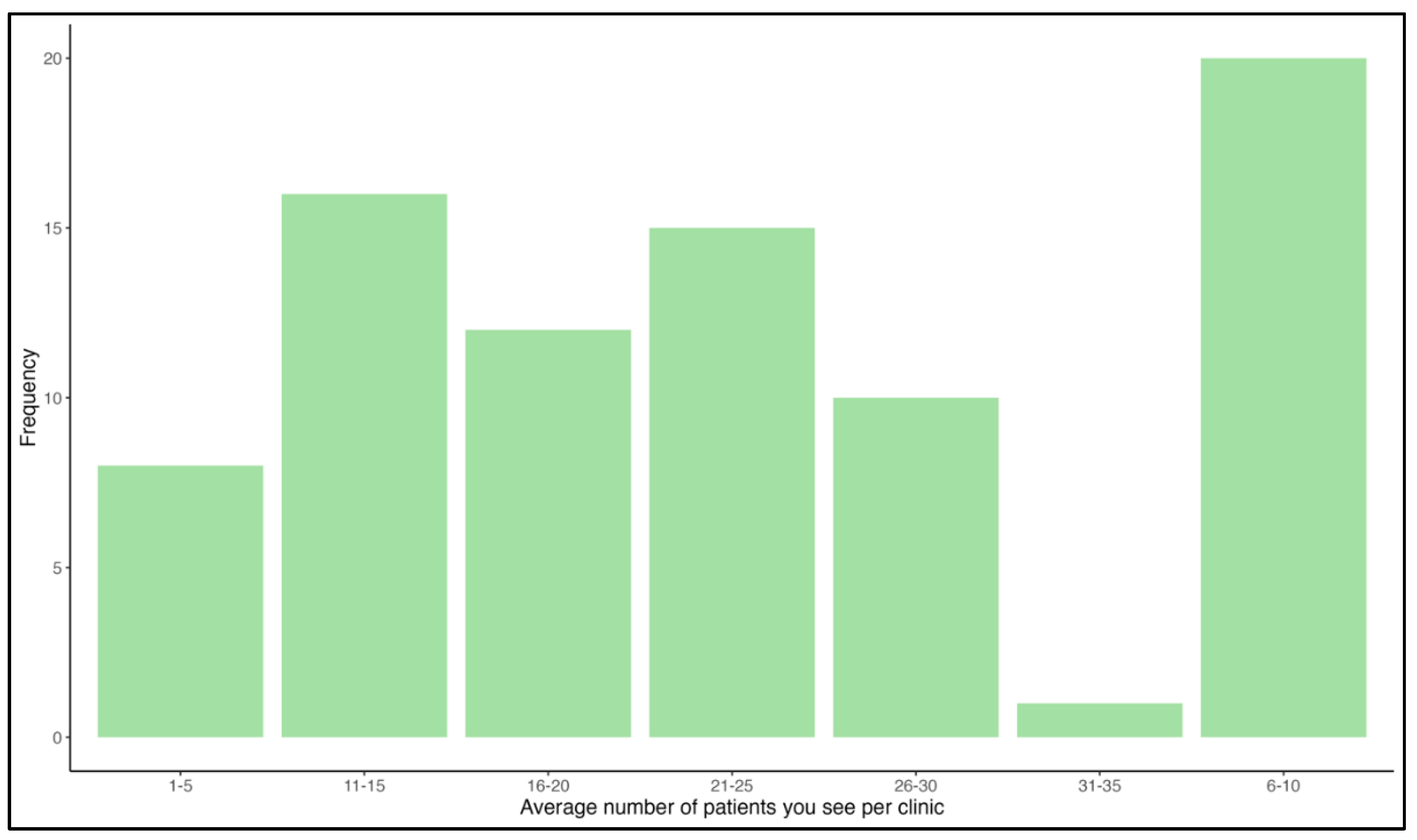

Figure 3 illustrates that most participants (24%) reported that the average number of patients they see per clinic was between 6-10 patients, followed by 20% who see an average of 11-15 patients, and 18% who see 21-25 patients per clinic.

3.4. Bivariate analysis

Bivariate analyses between two employment groups on multiple characteristics are summarized in

Table 4. Group 1 (n=18) was defined as participants who were employed within their first three months after graduating, and Group 2 (n=21) included participants who were employed after spending three months of unemployment since graduating. The two employment groups did not significantly differ in age (p=0.97), gender (p=1.00), or city of birth (p=0.13). However, the two groups significantly differed in their residency center (p=0.04).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze the pediatric neurology workforce in Saudi Arabia in terms of demographics, educational and research activity and level, and employment status. Furthermore, the study represents a contemporary update of previous studies [

7,

8] that analyzed the same workforce amid growing challenges and changes. The significance of this study is underscored by the growing population and the subsequent increase in referrals and counseling demands placed on pediatric neurologists [

11]. Furthermore, advancements in diagnostic modalities, particularly next-generation sequencing (NGS), have emerged as a pivotal technology for gene discovery, equipping clinicians with the capability to identify novel mutations [

12,

13]. Consequently, this has resulted in a notable rise in the detection of previously unknown mutations [

14], which are frequently encountered in pediatric neurology clinics. Nonetheless, this study presented evidence of a growing number of pediatric neurologists in-training in comparison to prior literature. A shift in their demographic data was also remarkable as the previous studies highlighted a major male predominance in the specialty reaching a percentage as high as 73% [

8] while our current study estimated male and female percentages of 46.34% and 53.66%, respectively. This remarkable change is consistent with growing trends of medical specialties becoming more feminized even in eastern-conservative communities [

15,

16,

17]. Despite the fact that more than two-thirds of participants are married (68.29%), 63.41% of participants had no form of health insurance. However, this could be attributed to the current reality of a universal healthcare model adopted in Saudi Arabia giving free access to all citizens to health services [

18] but this requires careful attention as the country shifts into privatizing the health sector and introducing amplifying the number of health insurance holders [

19]. This issue is of great importance as studies concluded a correlation between insurance and good health [

20] which is eventually reflected in patients in terms of the quality of services provided by their healthcare provider. The vast majority of participants were locally trained which confirms growing trends nationwide in expanding residency programs at the expense of international, government-funded, scholarships. The majority, nonetheless, are either trained or practicing in a main city leaving peripheral cities and provinces in need of intensive planning and strategies to ensure fair distribution of programs and care providers. The engagement in clinical pediatric neurology research remains low as our study reported. This issue was echoed in multiple medical specialties among Saudi trainees [

21] despite an increasing number of research resources and newly-introduced tools including artificial intelligent software. Such tools if acclimatized by trainees can potentially advance the practice [

22]. EEG and epilepsy was also the most prevalent type of fellowship training. Moreover, a concerning point has been risen in the current data in which nearly half of the participants (47.57%) experienced some form of delay in acquiring their first job after graduating from the residency program while others were either still in-training or obtained an immediate job following their graduation. The issue is that there were nearly 25.62% had their first job after 4-6 months of graduating and some reaching multiple years of unemployment (4.88%). The struggle remains in the reality of job listing in which pediatric neurologists continue to compete with general pediatricians for vacancies. An issue that could be addressed if independent job vacancies were offered to pediatric neurologists. Furthermore, in the previous workforce analysis it was found that nearly 18% of pediatric neurologists reported to >20 patients per clinic [

8], however, this number has increased according to our data in which 31.71% of participants reporting to see more than 20 patients per clinic (

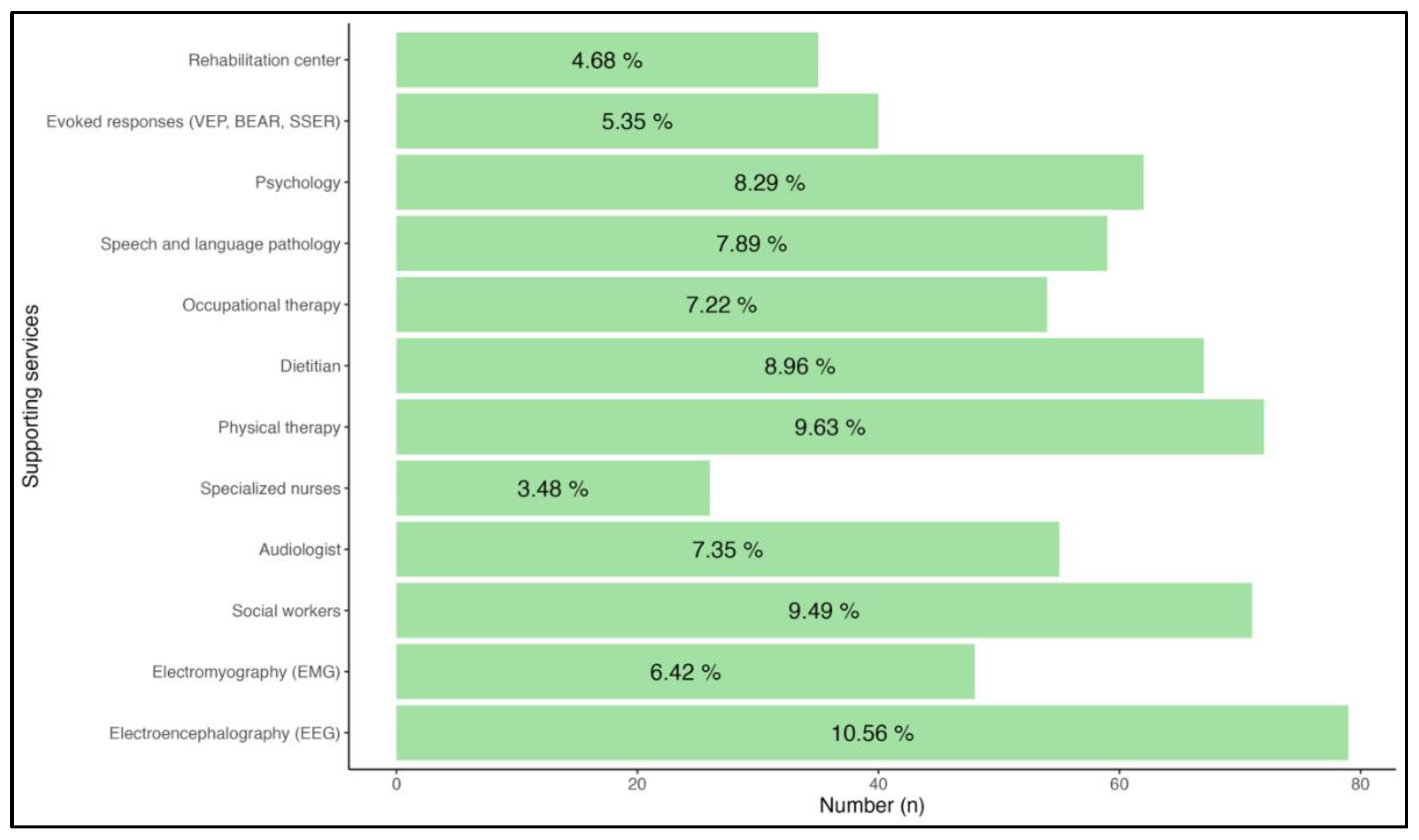

Figure 3). As for supporting services, EEG remains the leading service in the current study and in previous data (

Figure 4) [

8] while observing an increasing number of physical therapy at the expense of EMG which used to rank second [

8] as the leading service for pediatric neurologists while currently being third following physical therapy.

Due to the study design (cross-sectional), the absence of some participants in the study may cause selection bias. The lack of sufficient update and previous studies nationwide made it difficult to compare the findings to others. Unequal sampling can also be a potential limitation to the study. These limitations, however, were addressed by increasing the sample size.

5. Conclusions

Our analysis leads us to the conclusion that the demographic characteristics of the pediatric neurology workforce are undergoing significant transformations, particularly with an increasing number of female practitioners joining the field. However, it is crucial to note that the distribution of this workforce remains concentrated in limited areas across the country, primarily major cities, leaving peripheral cities in a perpetual need for qualified professionals. Real-life challenges, such as the delay in securing employment after graduation, have been comprehensively described and analyzed, but further evaluation by stakeholders is necessary to fully comprehend the multifaceted impact of such issues. Addressing these critical challenges that persist throughout the journey of pediatric neurologists should be prioritized. Enhancing employment opportunities and reducing staffing turnover are essential aspects that must be considered when formulating strategies in the field of pediatric neurology. Given the confined sample in this study, it is highly recommended that similar research efforts be supported and expanded to yield more detailed findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.B. and A.S.A.; methodology, A.K.B. and A.S.A.; software, A.S.A.; validation, A.S.A, and A.A.; formal analysis, A.A.; investigation, A.K.B., A.S.A., and A.A., AY.S.A; resources, A.K.B.; data curation, A.S.A, A.A., M.N.A., and M.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.B., A.S.A., A.A., AY.S.A., and M.A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.K.B.; visualization, A.A. and A.S.A.; supervision, A.K.B. and M.N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study aim, protocol, survey, and procedure obtained an ethical exemption on May 8, 2023 from the Unit of Biomedical Ethics Research Committee at the Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University under reference number 33-23. All participants were informed of the aim of the study and confidentiality, and their rights to refuse participation or withdraw at any point during their participation. Consent was collected prior to enrollment. All information was kept private and anonymous.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants were informed of the proposed study methods; a verbal and an informed written consent document was signed by those who agreed to participate.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are avail- able from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge the survey participants for their valuable time and the “Saudi Neuroscience Forum” group on WhatsApp for their profound assistance to reach participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO: Working together for health—The World Health Report 2006—World | ReliefWeb. Wrold Heal. Rep. 2006—Working Together Heal. (2006). Accessed: June 26, 2023. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/working-together-health-world-health-report-2006?gclid=Cj0KCQjw7uSkBhDGARIsAMCZNJu279g3Y5lzB1It3sEeBgpL9DTgj6mRHwW2uWU73rDO6WA7B3T39eQaAvqBEALw_wcB. [CrossRef]

- Khaliq AA: The Saudi health care system: a view from the minaret. World Health Popul. 2012, 13:52–64. [CrossRef]

- Salam AA, Elsegaey I, Khraif R, AlMutairi A, Aldosari A: Components and Public Health Impact of Population Growth in the Arab World. PLoS One. 2015, 10:e0124944. [CrossRef]

- al-Mubarak KA, Adamchak DJ: Fertility attitudes and behavior of Saudi Arabian students enrolled in U.S. universities. Soc Biol. 1994, 41:267–73. [CrossRef]

- GASTAT. Available online: https://database.stats.gov.sa/home/indicator/535 (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Al Salloum AA, El Mouzan MI, Al Omar AA, Al Herbish AS, Qurashi MM: The prevalence of neurological disorders in Saudi children: a community-based study. J Child Neurol. 2011, 26:21–4. [CrossRef]

- Jan MMS: Pediatric neurologists in Saudi Arabia: An audit of current practice. J Pediatr Neurol. 2005, 3:147–52.

- Al-Nahdi BM, Ashgar MW, Domyati MY, Alwadei AH, Albaradie RS, Jan MM: Pediatric Neurology Workforce in Saudi Arabia. J Pediatr Neurol. 2017, 15:166–70. [CrossRef]

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP: The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008, 61:344–9. [CrossRef]

- Kim H-Y: Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Restor Dent Endod. 2017, 42:152. [CrossRef]

- Ronen GM, Meaney BF: Pediatric neurology services in Canada: demand versus supply. J Child Neurol. 2003, 18:180–4. [CrossRef]

- Behjati S, Tarpey PS: What is next generation sequencing? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2013, 98:236–8. [CrossRef]

- Metzker ML: Sequencing technologies—the next generation. Nat Rev Genet. 2010, 11:31–46. [CrossRef]

- Kovesdi E, Ripszam R, Postyeni E, et al.: Whole Exome Sequencing in a Series of Patients with a Clinical Diagnosis of Tuberous Sclerosis Not Confirmed by Targeted TSC1/TSC2 Sequencing. Genes 2021, Vol 12, Page 1401. 2021, 12:1401. [CrossRef]

- Denekens JPM: The impact of feminisation on general practice. Acta Clin Belg. 2002, 57:5–10. [CrossRef]

- McKinstry B, Colthart I, Elliott K, Hunter C: The feminization of the medical work force, implications for Scottish primary care: a survey of Scottish general practitioners. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006, 6. [CrossRef]

- Maiorova T, Stevens F, Zee J Van Der, Boode B, Scherpbier A: Shortage in general practice despite the feminisation of the medical workforce: a seeming paradox? A cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008, 8:262. [CrossRef]

- Health Sector Transformation Program—Vision 2030. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/vrps/hstp/ (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Hazazi A, Wilson A, Larkin S: Reform of the Health Insurance Funding Model to Improve the Care of Noncommunicable Diseases Patients in Saudi Arabia. Healthc (Basel, Switzerland). 2022, 10:. [CrossRef]

- Levy H, Meltzer D: The Impact of Health Insurance on Health. [CrossRef]

- Maghrabi Y, Baeesa M, Kattan J, Altaf A, Baeesa S: Level of evidence of abdominal surgery clinical research in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2017, 38:788–93.

- None A, P M, M P, VK R: Overview of artificial intelligence in medicine. J Fam Med Prim care. 2019, 8:2328. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).