Submitted:

11 July 2023

Posted:

12 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Exploring the distinctions amongst diverse databases

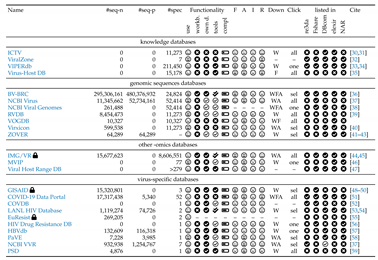

: To access the complete range of features and download data, user authentication is required; #seq-n – number of nucleotide sequences; #seq-p – number of protein sequences; #spec – number of species; – – not known/ no access; use – subjective impression of usability workb. – workbench; own d. – own data: the possibility to work with personal data; compl. – complexity of data base, ranging from simple (

: To access the complete range of features and download data, user authentication is required; #seq-n – number of nucleotide sequences; #seq-p – number of protein sequences; #spec – number of species; – – not known/ no access; use – subjective impression of usability workb. – workbench; own d. – own data: the possibility to work with personal data; compl. – complexity of data base, ranging from simple ( ) to extensive (

) to extensive ( ); tools – availability of tools and a quantitative ranking:

); tools – availability of tools and a quantitative ranking:  – a lot of tools;

– a lot of tools;  – available;

– available;  – only few tools;

– only few tools;  – no tools available; F – Findability; A – Accessibility; I – Interoperability; R – Reusability (see Table S5 and Figure S1); Down – downloadable via Web (W), FTP (F), and API (A); Click – by one click no data (no), one dataset (one), selected data (sel), or all data can be download (all); re3da – re3data; Fshare – FAIRsharing.org; DBcom– Database Commons; elexir–ELEXIR bio.tools; NAR – NAR Database list; for VVR: just one of the seven VVR resources is listed;

– no tools available; F – Findability; A – Accessibility; I – Interoperability; R – Reusability (see Table S5 and Figure S1); Down – downloadable via Web (W), FTP (F), and API (A); Click – by one click no data (no), one dataset (one), selected data (sel), or all data can be download (all); re3da – re3data; Fshare – FAIRsharing.org; DBcom– Database Commons; elexir–ELEXIR bio.tools; NAR – NAR Database list; for VVR: just one of the seven VVR resources is listed;

: To access the complete range of features and download data, user authentication is required; #seq-n – number of nucleotide sequences; #seq-p – number of protein sequences; #spec – number of species; – – not known/ no access; use – subjective impression of usability workb. – workbench; own d. – own data: the possibility to work with personal data; compl. – complexity of data base, ranging from simple (

: To access the complete range of features and download data, user authentication is required; #seq-n – number of nucleotide sequences; #seq-p – number of protein sequences; #spec – number of species; – – not known/ no access; use – subjective impression of usability workb. – workbench; own d. – own data: the possibility to work with personal data; compl. – complexity of data base, ranging from simple ( ) to extensive (

) to extensive ( ); tools – availability of tools and a quantitative ranking:

); tools – availability of tools and a quantitative ranking:  – a lot of tools;

– a lot of tools;  – available;

– available;  – only few tools;

– only few tools;  – no tools available; F – Findability; A – Accessibility; I – Interoperability; R – Reusability (see Table S5 and Figure S1); Down – downloadable via Web (W), FTP (F), and API (A); Click – by one click no data (no), one dataset (one), selected data (sel), or all data can be download (all); re3da – re3data; Fshare – FAIRsharing.org; DBcom– Database Commons; elexir–ELEXIR bio.tools; NAR – NAR Database list; for VVR: just one of the seven VVR resources is listed;

– no tools available; F – Findability; A – Accessibility; I – Interoperability; R – Reusability (see Table S5 and Figure S1); Down – downloadable via Web (W), FTP (F), and API (A); Click – by one click no data (no), one dataset (one), selected data (sel), or all data can be download (all); re3da – re3data; Fshare – FAIRsharing.org; DBcom– Database Commons; elexir–ELEXIR bio.tools; NAR – NAR Database list; for VVR: just one of the seven VVR resources is listed;

2.1. Knowledge databases

2.2. Databases containing virus sequences

2.3. Omics databases

2.3.1. Specific databases

2.3.2. Non-viral specific databases

2.3.3. Other databases

2.3.4. FAIR evaluation

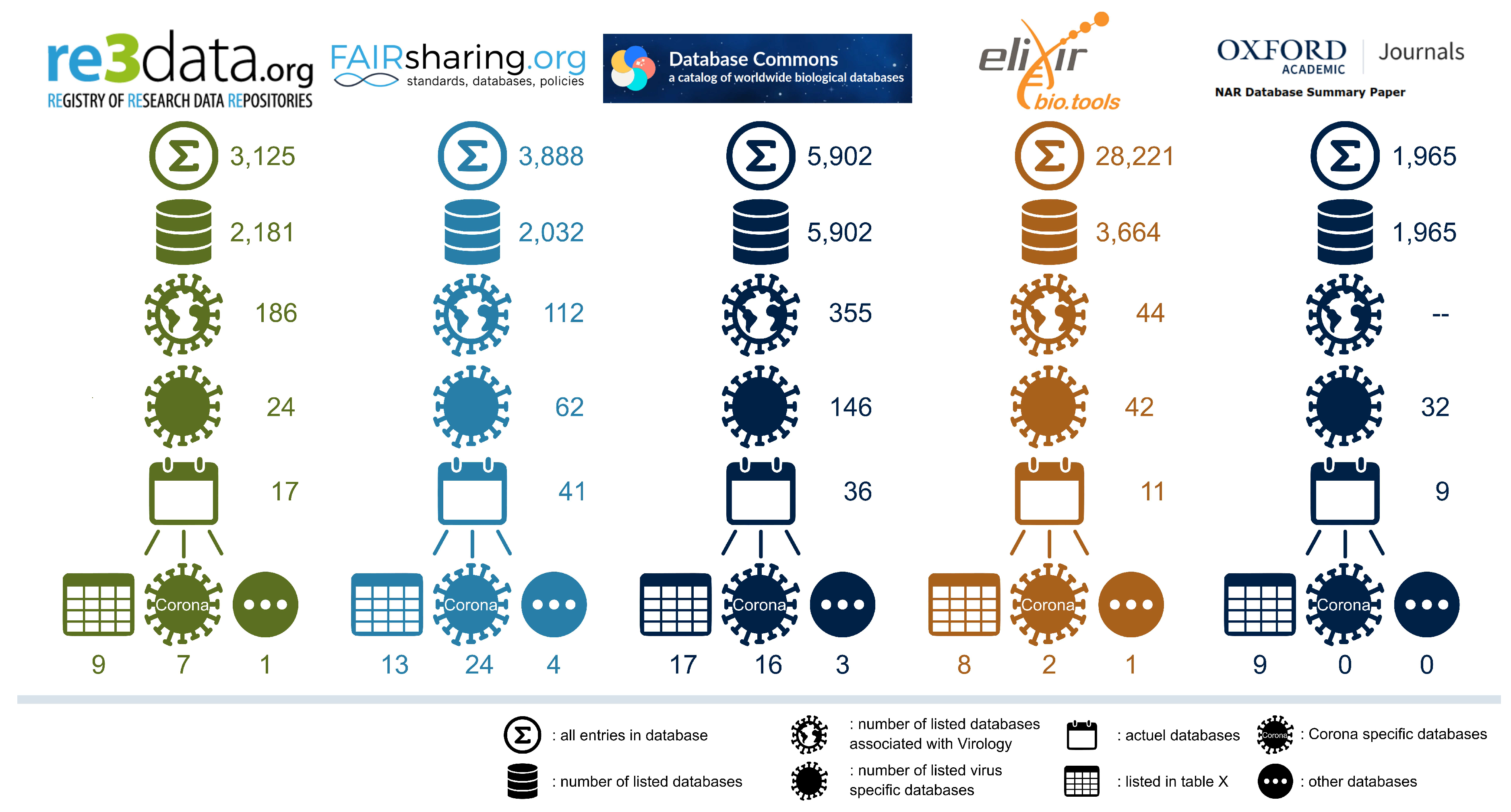

2.4. Catalogs of databases

3. Evaluation of errors in the NCBI and BV-BRC

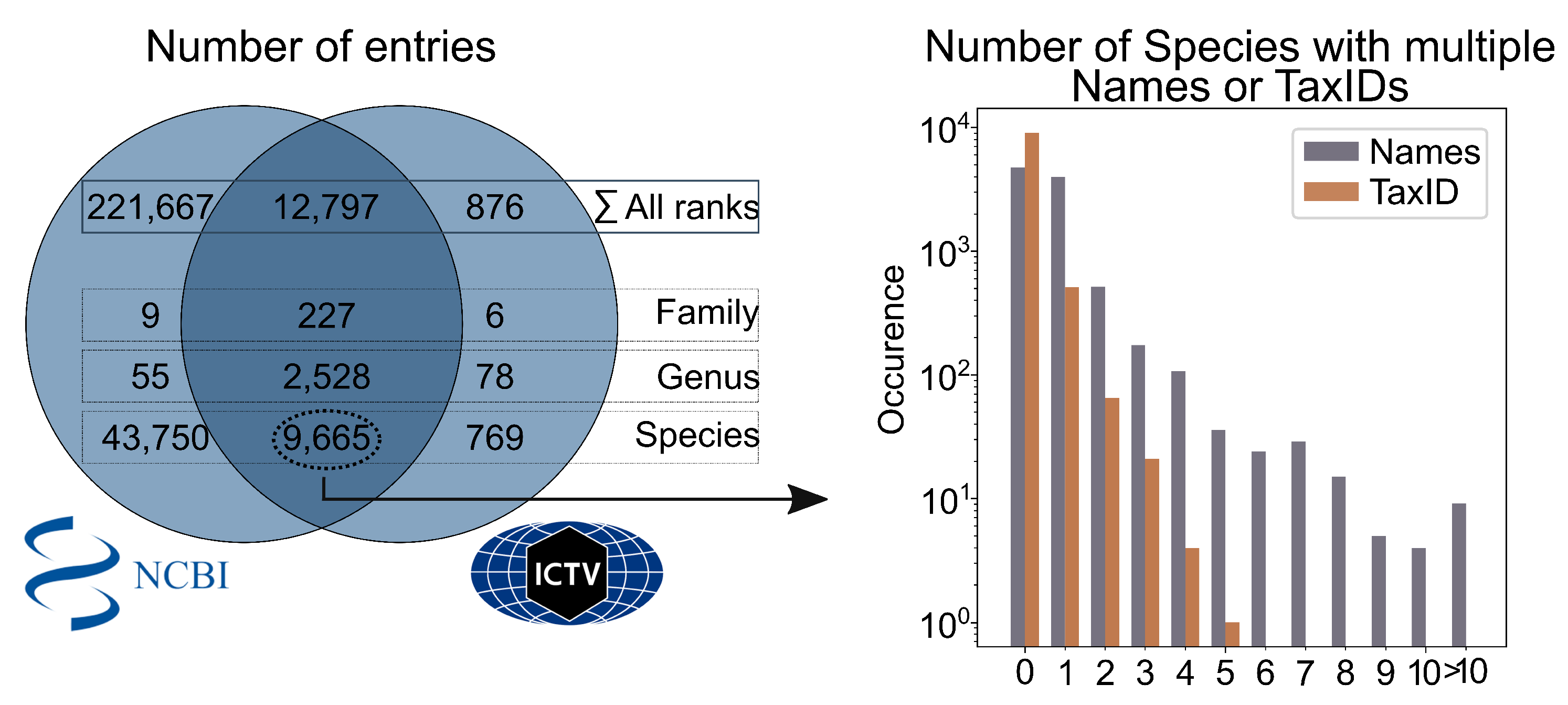

3.1. Taxonomy errors

3.2. Naming and labeling errors

3.3. Missing information

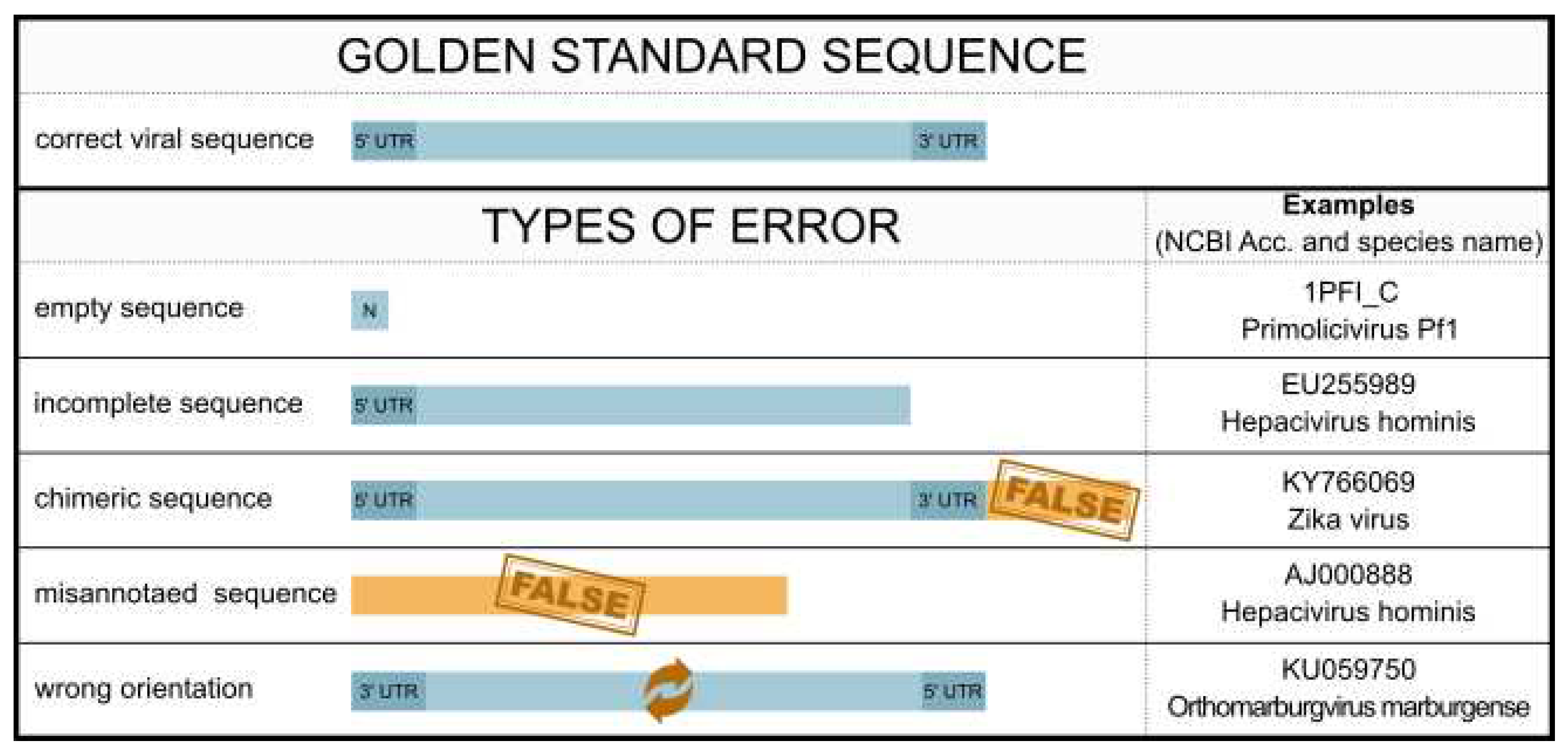

3.4. Sequence errors

3.5. Sequence orientation error

3.6. Chimeric sequences

4. Outlook and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hendrix, R.W.; Smith, M.C.M.; Burns, R.N.; Ford, M.E.; Hatfull, G.F. Evolutionary relationships among diverse bacteriophages and prophages: All the world’s a phage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1999, 96, 2192–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushegian, A. Are there 1031 virus particles on earth, or more, or fewer? Journal of bacteriology 2020, 202, e00052–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubaugh, N.D.; Ladner, J.T.; Lemey, P.; Pybus, O.G.; Rambaut, A.; Holmes, E.C.; Andersen, K.G. Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty-first century. Nature Microbiology 2019, 4, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, G.L.; MacCannell, D.R.; Taylor, J.; Carleton, H.A.; Neuhaus, E.B.; Bradbury, R.S.; Posey, J.E.; Gwinn, M. Pathogen Genomics in Public Health. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 381, 2569–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmstrom, C.M.; Martin, M.D.; Gagnevin, L. Exploring the emergence and evolution of plant pathogenic microbes using historical and paleontological sources. Annual Review of Phytopathology 2022, 60, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.A.C.; Boonham, N.; Adams, I.P.; Fox, A. Historical virus isolate collections: An invaluable resource connecting plant virology’s pre-sequencing and post-sequencing eras. Plant Pathology 2021, 70, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, S.; Adriaenssens, E.M.; Dutilh, B.E.; Koonin, E.V.; Kropinski, A.M.; Krupovic, M.; Kuhn, J.H.; Lavigne, R.; Brister, J.R.; Varsani, A.; Amid, C.; Aziz, R.K.; Bordenstein, S.R.; Bork, P.; Breitbart, M.; Cochrane, G.R.; Daly, R.A.; Desnues, C.; Duhaime, M.B.; Emerson, J.B.; Enault, F.; Fuhrman, J.A.; Hingamp, P.; Hugenholtz, P.; Hurwitz, B.L.; Ivanova, N.N.; Labonté, J.M.; Lee, K.B.; Malmstrom, R.R.; Martinez-Garcia, M.; Mizrachi, I.K.; Ogata, H.; Páez-Espino, D.; Petit, M.A.; Putonti, C.; Rattei, T.; Reyes, A.; Rodriguez-Valera, F.; Rosario, K.; Schriml, L.; Schulz, F.; Steward, G.F.; Sullivan, M.B.; Sunagawa, S.; Suttle, C.A.; Temperton, B.; Tringe, S.G.; Thurber, R.V.; Webster, N.S.; Whiteson, K.L.; Wilhelm, S.W.; Wommack, K.E.; Woyke, T.; Wrighton, K.C.; Yilmaz, P.; Yoshida, T.; Young, M.J.; Yutin, N.; Allen, L.Z.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Eloe-Fadrosh, E.A. Minimum Information about an Uncultivated Virus Genome (MIUViG). Nature Biotechnology 2019, 37, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauber, C.; Seitz, S. Opportunities and Challenges of Data-Driven Virus Discovery. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, Y.; Ideta, T.; Hirata, A.; Hatano, K.; Tomita, H.; Okada, H.; Shimizu, M.; Tanaka, T.; Hara, A. Virus-Driven Carcinogenesis. Cancers 2021, 13, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, D.; Daszak, P.; Wolfe, N.D.; Gao, G.F.; Morel, C.M.; Morzaria, S.; Pablos-Méndez, A.; Tomori, O.; Mazet, J.A.K. The Global Virome Project. Science 2018, 359, 872–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, D.; Watson, B.; Togami, E.; Daszak, P.; Mazet, J.A.; Chrisman, C.J.; Rubin, E.M.; Wolfe, N.; Morel, C.M.; Gao, G.F.; others. Building a global atlas of zoonotic viruses. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2018, 96, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Rodriguez, T.M.; Hollister, E.B. Unraveling the viral dark matter through viral metagenomics. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Zheng, K.; McMinn, A.; Wang, M. Expanding diversity and ecological roles of RNA viruses. Trends in Microbiology 2023, 31, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C.; Taylor, J.; Lin, V.; Altman, T.; Barbera, P.; Meleshko, D.; Lohr, D.; Novakovsky, G.; Buchfink, B.; Al-Shayeb, B.; Banfield, J.F.; de la Peña, M.; Korobeynikov, A.; Chikhi, R.; Babaian, A. Petabase-scale sequence alignment catalyses viral discovery. Nature 2022, 602, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Balbin-Ramon, G.J.; Rabaan, A.A.; Sah, R.; Dhama, K.; Paniz-Mondolfi, A.; Pagliano, P.; Esposito, S. Genomic Epidemiology and its importance in the study of the COVID-19 pandemic. Le Infezioni in Medicina 2020, 28, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martin, J.; Klapsa, D.; Wilton, T.; Zambon, M.; Bentley, E.; Bujaki, E.; Fritzsche, M.; Mate, R.; Majumdar, M. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 in Sewage: Evidence of Changes in Virus Variant Predominance during COVID-19 Pandemic. Viruses 2020, 12, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Qian, Y.; Qi, X.; Shen, B. Databases, Knowledgebases, and Software Tools for Virus Informatics. In Translational Informatics: Prevention and Treatment of Viral Infections; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Crabtree, J.; Dillo, I.; Downs, R.R.; Edmunds, R.; Giaretta, D.; De Giusti, M.; L’Hours, H.; Hugo, W.; Jenkyns, R.; Khodiyar, V.; Martone, M.E.; Mokrane, M.; Navale, V.; Petters, J.; Sierman, B.; Sokolova, D.V.; Stockhause, M.; Westbrook, J. The TRUST Principles for digital repositories. Scientific Data 2020, 7, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wren, J.D.; Bateman, A. Databases, data tombs and dust in the wind. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 2127–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, S.; Salwinski, L.; Kerrien, S.; Montecchi-Palazzi, L.; Oesterheld, M.; Stümpflen, V.; Ceol, A.; Chatr-Aryamontri, A.; Armstrong, J.; Woollard, P.; others. The minimum information required for reporting a molecular interaction experiment (MIMIx). Nature biotechnology 2007, 25, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, S.; Adriaenssens, E.M.; Dutilh, B.E.; Koonin, E.V.; Kropinski, A.M.; Krupovic, M.; Kuhn, J.H.; Lavigne, R.; Brister, J.R.; Varsani, A.; others. Minimum information about an uncultivated virus genome (MIUViG). Nature biotechnology 2019, 37, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Priyadarshini, P.; Vrati, S. Unraveling the web of viroinformatics: computational tools and databases in virus research. Journal of virology 2015, 89, 1489–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, K.; Upton, C. Virus Databases. Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences, 2017; B978–0–12–801238–3.95728–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, S.A.; McQuilton, P.; Rocca-Serra, P.; Gonzalez-Beltran, A.; Izzo, M.; Lister, A.L.; Thurston, M.; Community, F. FAIRsharing as a community approach to standards, repositories and policies. Nature biotechnology 2019, 37, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Zou, D.; Liu, L.; Shireen, H.; Abbasi, A.A.; Bateman, A.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, W.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, Z. Database Commons: A Catalog of Worldwide Biological Databases. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ison, J.; Rapacki, K.; Ménager, H.; Kalaš, M.; Rydza, E.; Chmura, P.; Anthon, C.; Beard, N.; Berka, K.; Bolser, D.; others. Tools and data services registry: a community effort to document bioinformatics resources. Nucleic acids research 2016, 44, D38–D47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigden, D.J.; Fernández, X.M. The 2023 Nucleic Acids Research Database Issue and the online molecular biology database collection. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, D1–D8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; others. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific data 2016, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, A.; Canakoglu, A.; Masseroli, M.; Pinoli, P.; Ceri, S. A review on viral data sources and search systems for perspective mitigation of COVID-19. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2020, bbaa359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, E.J.; Dempsey, D.M.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Orton, R.J.; Siddell, S.G.; Smith, D.B. Virus taxonomy: the database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Nucleic acids research 2018, 46, D708–D717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.J.; Siddell, S.G.; Lefkowitz, E.J.; Mushegian, A.R.; Adriaenssens, E.M.; Dempsey, D.M.; Dutilh, B.E.; Harrach, B.; Harrison, R.L.; Hendrickson, R.C.; others. Changes to virus taxonomy and the Statutes ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2020). 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulo, C.; De Castro, E.; Masson, P.; Bougueleret, L.; Bairoch, A.; Xenarios, I.; Le Mercier, P. ViralZone: a knowledge resource to understand virus diversity. Nucleic acids research 2011, 39, D576–D582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Tripp, M.; Shepherd, C.M.; Borelli, I.A.; Venkataraman, S.; Lander, G.; Natarajan, P.; Johnson, J.E.; Brooks III, C.L.; Reddy, V.S. VIPERdb2: an enhanced and web API enabled relational database for structural virology. Nucleic acids research 2009, 37, D436–D442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel-Garcia, D.; Santoyo-Rivera, N.; Ho, P.; Carrillo-Tripp, M.; Iii, C.L.B.; Johnson, J.E.; Reddy, V.S. VIPERdb v3. 0: a structure-based data analytics platform for viral capsids. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, D809–D816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihara, T.; Nishimura, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Nishiyama, H.; Yoshikawa, G.; Uehara, H.; Hingamp, P.; Goto, S.; Ogata, H. Linking virus genomes with host taxonomy. Viruses 2016, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, R.D.; Assaf, R.; Brettin, T.; Conrad, N.; Cucinell, C.; Davis, J.J.; Dempsey, D.M.; Dickerman, A.; Dietrich, E.M.; Kenyon, R.W.; others. Introducing the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC): a resource combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic acids research 2023, 51, D678–D689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, E.L.; Zhdanov, S.A.; Bao, Y.; Blinkova, O.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Ostapchuck, Y.; Schäffer, A.A.; Brister, J.R. Virus Variation Resource–improved response to emergent viral outbreaks. Nucleic acids research 2017, 45, D482–D490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brister, J.R.; Ako-Adjei, D.; Bao, Y.; Blinkova, O. NCBI viral genomes resource. Nucleic acids research 2015, 43, D571–D577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodacre, N.; Aljanahi, A.; Nandakumar, S.; Mikailov, M.; Khan, A.S. A reference viral database (RVDB) to enhance bioinformatics analysis of high-throughput sequencing for novel virus detection. MSphere 2018, 3, e00069–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudla, M.; Gutowska, K.; Synak, J.; Weber, M.; Bohnsack, K.S.; Lukasiak, P.; Villmann, T.; Blazewicz, J.; Szachniuk, M. Virxicon: a lexicon of viral sequences. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 5507–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Jin, Q. DBatVir: the database of bat-associated viruses. Database 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, B.; Wu, Z.; Jin, Q.; Yang, J. DRodVir: A resource for exploring the virome diversity in rodents. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2017, 44, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, B.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, Z.; Yang, J. ZOVER: the database of zoonotic and vector-borne viruses. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, D943–D949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, I.M.A.; Chu, K.; Palaniappan, K.; Ratner, A.; Huang, J.; Huntemann, M.; Hajek, P.; Ritter, S.; Varghese, N.; Seshadri, R.; others. The IMG/M data management and analysis system v. 6.0: new tools and advanced capabilities. Nucleic acids research 2021, 49, D751–D763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, A.P.; Nayfach, S.; Chen, I.M.A.; Palaniappan, K.; Ratner, A.; Chu, K.; Ritter, S.J.; Reddy, T.; Mukherjee, S.; Schulz, F.; others. IMG/VR v4: an expanded database of uncultivated virus genomes within a framework of extensive functional, taxonomic, and ecological metadata. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, D733–D743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Fan, W.; Li, Q.; Wang, D.; Wen, M.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y. MVIP: multi-omics portal of viral infection. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, D817–D827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamy-Besnier, Q.; Brancotte, B.; Ménager, H.; Debarbieux, L. Viral Host Range database, an online tool for recording, analyzing and disseminating virus–host interactions. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, Y.; McCauley, J. GISAID: Global initiative on sharing all influenza data–from vision to reality. Eurosurveillance 2017, 22, 30494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbe, S.; Buckland-Merrett, G. Data, disease and diplomacy: GISAID’s innovative contribution to global health. Global challenges 2017, 1, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, S.; Gurry, C.; Freitas, L.; Schultz, M.B.; Bach, G.; Diallo, A.; Akite, N.; Ho, J.; Lee, R.T.; Yeo, W.; others. GISAID’s role in pandemic response. China CDC Weekly 2021, 3, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.W.; Lopez, R.; Rahman, N.; Allen, S.G.; Aslam, R.; Buso, N.; Cummins, C.; Fathy, Y.; Felix, E.; Glont, M.; others. The COVID-19 Data Portal: accelerating SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 research through rapid open access data sharing. Nucleic acids research 2021, 49, W619–W623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzou, P.L.; Tao, K.; Pond, S.L.K.; Shafer, R.W. Coronavirus Resistance Database (CoV-RDB): SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility to monoclonal antibodies, convalescent plasma, and plasma from vaccinated persons. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0261045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiken, C.; Korber, B.; Shafer, R.W. HIV sequence databases. AIDS reviews 2003, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuiken, C.; Yoon, H.; Abfalterer, W.; Gaschen, B.; Lo, C.; Korber, B. Viral genome analysis and knowledge management. In Data Mining for Systems Biology; Springer, 2013; pp. 253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer, R.W. Rationale and uses of a public HIV drug-resistance database. The Journal of infectious diseases 2006, 194, S51–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, S.Y.; Gonzales, M.J.; Kantor, R.; Betts, B.J.; Ravela, J.; Shafer, R.W. Human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase and protease sequence database. Nucleic acids research 2003, 31, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayer, J.; Jadeau, F.; Deleage, G.; Kay, A.; Zoulim, F.; Combet, C. HBVdb: a knowledge database for Hepatitis B Virus. Nucleic acids research 2013, 41, D566–D570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Doorslaer, K.; Li, Z.; Xirasagar, S.; Maes, P.; Kaminsky, D.; Liou, D.; Sun, Q.; Kaur, R.; Huyen, Y.; McBride, A.A. The Papillomavirus Episteme: a major update to the papillomavirus sequence database. Nucleic acids research 2017, 45, D499–D506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Shan, J.; Hu, W.S.; Halvas, E.K.; Mellors, J.W.; Coffin, J.M.; Kearney, M.F. HIV proviral sequence database: a new public database for near full-length HIV proviral sequences and their meta-analyses. AIDS research and human retroviruses 2020, 36, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddell, S.G.; Smith, D.B.; Adriaenssens, E.; Alfenas-Zerbini, P.; Dutilh, B.E.; Garcia, M.L.; Junglen, S.; Krupovic, M.; Kuhn, J.H.; Lambert, A.J.; Lefkowitz, E.J.; Łobocka, M.; Mushegian, A.R.; Oksanen, H.M.; Robertson, D.L.; Rubino, L.; Sabanadzovic, S.; Simmonds, P.; Suzuki, N.; Van Doorslaer, K.; Vandamme, A.M.; Varsani, A.; Zerbini, F.M. Virus taxonomy and the role of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). The Journal of General Virology 2023, 104, 001840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, U. UniProt: the Universal Protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, D523–D531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalvari, I.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Ontiveros-Palacios, N.; Argasinska, J.; Lamkiewicz, K.; Marz, M.; Griffiths-Jones, S.; Toffano-Nioche, C.; Gautheret, D.; Weinberg, Z.; others. Rfam 14: expanded coverage of metagenomic, viral and microRNA families. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, D192–D200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Blum, M.; Chuguransky, S.; Grego, T.; Pinto, B.L.; Salazar, G.A.; Bileschi, M.L.; Bork, P.; Bridge, A.; Colwell, L.; others. InterPro in 2022. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, D418–D427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.L.; Barrett, T.; Benson, D.A.; Bryant, S.H.; Canese, K.; Chetvernin, V.; Church, D.M.; DiCuccio, M.; Edgar, R.; Federhen, S.; others. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic acids research 2007, 35, D5–D12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic acids research 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Science 2019, 28, 1947–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, D587–D592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozomara, A.; Birgaoanu, M.; Griffiths-Jones, S. miRBase: from microRNA sequences to function. Nucleic acids research 2019, 47, D155–D162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, B.; McMahon, D.P.; Hufsky, F.; Beer, M.; Deng, L.; Mercier, P.L.; Palmarini, M.; Thiel, V.; Marz, M. A new era of virus bioinformatics. Virus Research 2018, 251, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufsky, F.; Abecasis, A.; Agudelo-Romero, P.; Bletsa, M.; Brown, K.; Claus, C.; Deinhardt-Emmer, S.; Deng, L.; Friedel, C.C.; Gismondi, M.I.; Kostaki, E.G.; Kühnert, D.; Kulkarni-Kale, U.; Metzner, K.J.; Meyer, I.M.; Miozzi, L.; Nishimura, L.; Paraskevopoulou, S.; Pérez-Cataluña, A.; Rahlff, J.; Thomson, E.; Tumescheit, C.; van der Hoek, L.; Van Espen, L.; Vandamme, A.M.; Zaheri, M.; Zuckerman, N.; Marz, M. Women in the European Virus Bioinformatics Center. Viruses 2022, 14, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolduc, B.; Youens-Clark, K.; Roux, S.; Hurwitz, B.L.; Sullivan, M.B. iVirus: facilitating new insights in viral ecology with software and community data sets imbedded in a cyberinfrastructure. The ISME journal 2017, 11, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolduc, B.; Zablocki, O.; Guo, J.; Zayed, A.A.; Vik, D.; Dehal, P.; Wood-Charlson, E.M.; Arkin, A.; Merchant, N.; Pett-Ridge, J.; others. iVirus 2.0: Cyberinfrastructure-supported tools and data to power DNA virus ecology. ISME Communications 2021, 1, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, S.I.; Fina, F.; Psalios, M.; Ryal, S.; Lebl, T.; Clements, A. Integration of an Active Research Data System with a Data Repository to Streamline the Research Data Lifecyle: Pure-NOMAD Case Study. International Journal of Digital Curation 2017, 12, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, D.; Sterk, P.; Kottmann, R.; De Smet, J.W.; Amaral-Zettler, L.; Cochrane, G.; Cole, J.R.; Davies, N.; Dawyndt, P.; Garrity, G.M.; Gilbert, J.A.; Glöckner, F.O.; Hirschman, L.; Klenk, H.P.; Knight, R.; Kyrpides, N.; Meyer, F.; Karsch-Mizrachi, I.; Morrison, N.; Robbins, R.; San Gil, I.; Sansone, S.; Schriml, L.; Tatusova, T.; Ussery, D.; Yilmaz, P.; White, O.; Wooley, J.; Caporaso, G. Genomic standards consortium projects. Standards in Genomic Sciences 2014, 9, 599–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, A.; Guizzardi, G.; Pastor, O.; Storey, V.C. Semantic interoperability: ontological unpacking of a viral conceptual model. BMC Bioinformatics 2022, 23, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López, R.; Pérez-Brocal, V.; Moya, A. Beyond cells–The virome in the human holobiont. Microbial Cell 2019, 6, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoch, C.L.; Ciufo, S.; Domrachev, M.; Hotton, C.L.; Kannan, S.; Khovanskaya, R.; Leipe, D.; Mcveigh, R.; O’Neill, K.; Robbertse, B.; others. NCBI Taxonomy: a comprehensive update on curation, resources and tools. Database 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Chotewutmontri, S.; Wolf, S.; Klos, U.; Schmitz, M.; Dürst, M.; Schwarz, E. Multiplex identification of human papillomavirus 16 DNA integration sites in cervical carcinomas. PloS one 2013, 8, e66693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasekhian, M.; Roohvand, F.; Habtemariam, S.; Marzbany, M.; Kazemimanesh, M. The Role of 3’UTR of RNA Viruses on mRNA Stability and Translation Enhancement. Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 21, 2389–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbini, F.M.; Siddell, S.G.; Mushegian, A.R.; Walker, P.J.; Lefkowitz, E.J.; Adriaenssens, E.M.; Alfenas-Zerbini, P.; Dutilh, B.E.; García, M.L.; Junglen, S.; others. Differentiating between viruses and virus species by writing their names correctly. Archives of virology 2022, 167, 1231–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, V.G.; Emrich, S.J.; Giraldo-Calderón, G.I.; Harb, O.S.; Newman, R.M.; Pickett, B.E.; Schriml, L.M.; Stockwell, T.B.; Stoeckert Jr, C.J.; Sullivan, D.E.; others. Standardized metadata for human pathogen/vector genomic sequences. PloS one 2014, 9, e99979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Adriaenssens, E.M.; Tolstoy, I.; Kropinski, A.M. Phage Annotation Guide: Guidelines for Assembly and High-Quality Annotation. PHAGE 2021, 2, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncoroni, M.; Droesbeke, B.; Eguinoa, I.; De Ruyck, K.; D’Anna, F.; Yusuf, D.; Grüning, B.; Backofen, R.; Coppens, F. A SARS-CoV-2 sequence submission tool for the European Nucleotide Archive. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 3983–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäffer, A.A.; Hatcher, E.L.; Yankie, L.; Shonkwiler, L.; Brister, J.R.; Karsch-Mizrachi, I.; Nawrocki, E.P. VADR: validation and annotation of virus sequence submissions to GenBank. BMC bioinformatics 2020, 21, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo Mühr, L.S.; Lagheden, C.; Hassan, S.S.; Kleppe, S.N.; Hultin, E.; Dillner, J. De novo sequence assembly requires bioinformatic checking of chimeric sequences. Plos one 2020, 15, e0237455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-López, R.; Vázquez-Castellanos, J.F.; Moya, A. Fragmentation and coverage variation in viral metagenome assemblies, and their effect in diversity calculations. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 2015, 3, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orakov, A.; Fullam, A.; Coelho, L.P.; Khedkar, S.; Szklarczyk, D.; Mende, D.R.; Schmidt, T.S.; Bork, P. GUNC: detection of chimerism and contamination in prokaryotic genomes. Genome biology 2021, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, T.D.; Clooney, A.G.; Ryan, F.J.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C. Choice of assembly software has a critical impact on virome characterisation. Microbiome 2019, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzberg, S.L.; Phillippy, A.M.; Zimin, A.; Puiu, D.; Magoc, T.; Koren, S.; Treangen, T.J.; Schatz, M.C.; Delcher, A.L.; Roberts, M.; others. GAGE: A critical evaluation of genome assemblies and assembly algorithms. Genome research 2012, 22, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of molecular biology 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).