Submitted:

11 July 2023

Posted:

13 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Theoretical Background

1.3.1. Health Belief Model (HBM)

1.3.2. Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

1.3.3. Transtheoretical Model/Stages of Change Model (TTM)

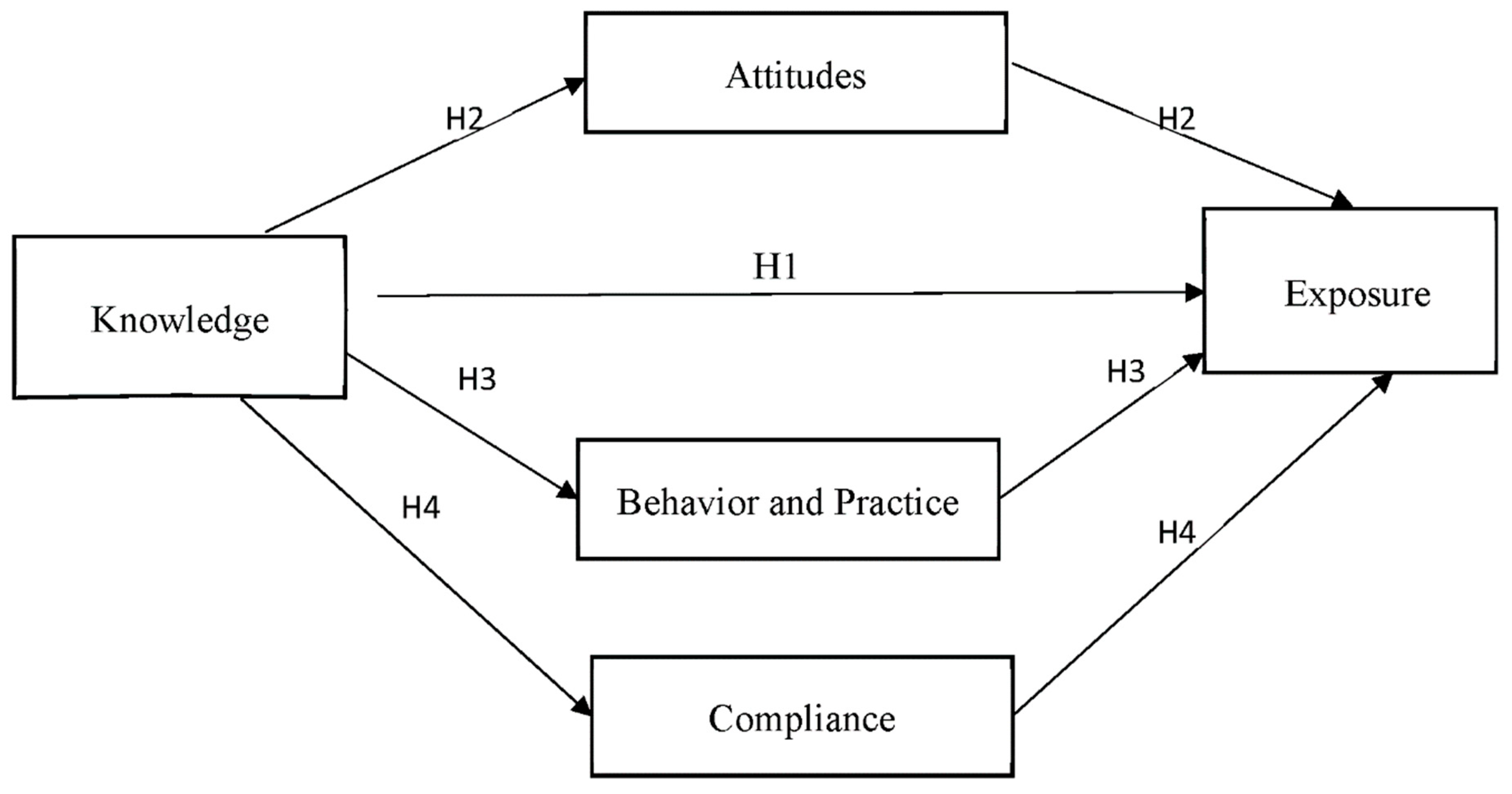

1.3.4. Model Used in the Study

2. Methods

3. Data Analysis and Results

3.1.1. Descriptive Analysis

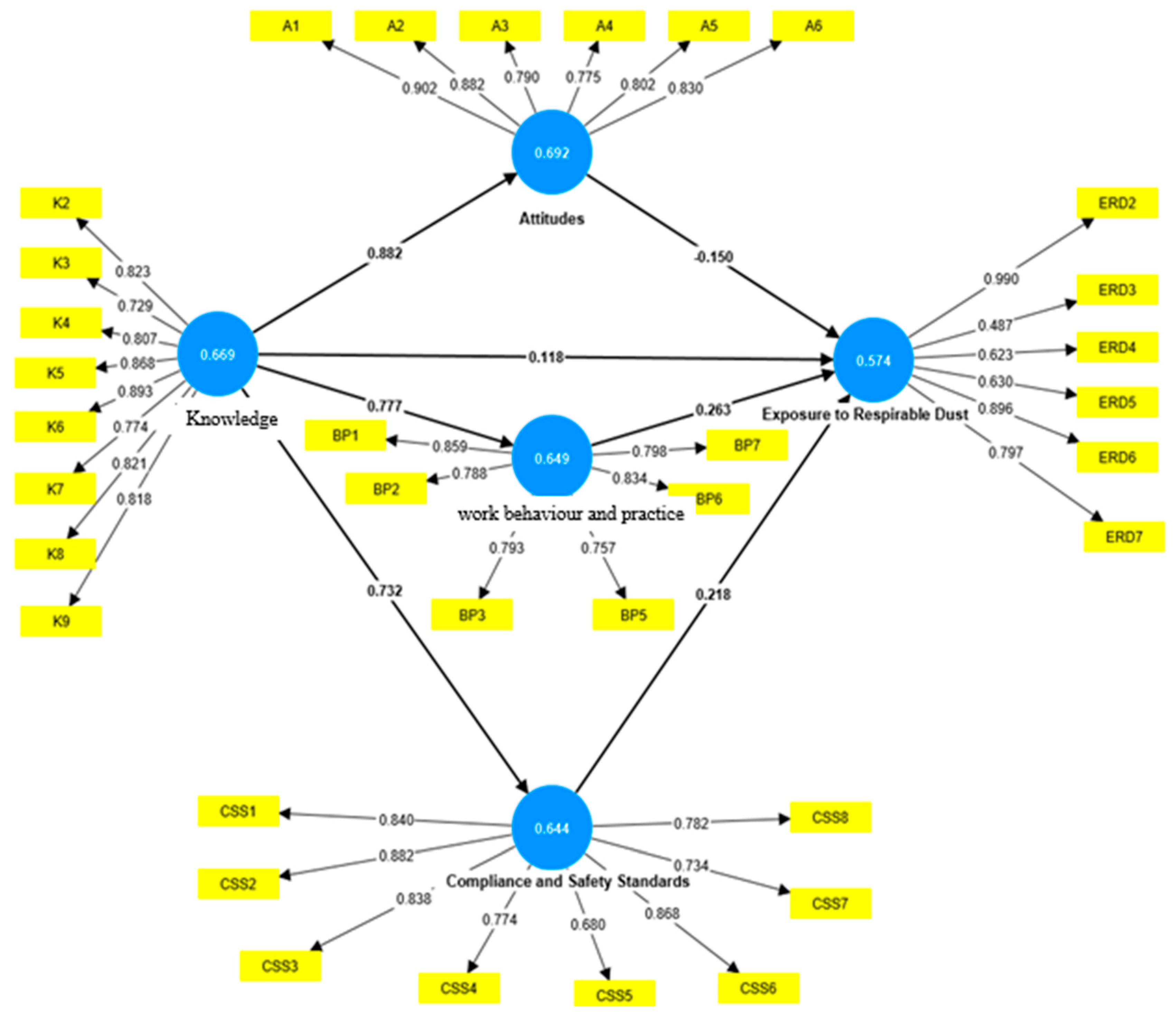

3.1.2. Outer Loadings

3.1.3. Convergent Validity

3.1.4. Discriminant Validity

3.1.5. Collinearity Assessment for the Structural Model in PLS-SEM

3.1.6. Coefficient of Determination (R2)

3.1.7. Path Coefficient

3.1.8. Predictive Relevance (Q2)

3.1.9. Effect Size

3.1.10. Multi-Group Analysis

3.1.11. Hypotheses Testing Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Ethical Approval

Consent for Publication

Availability of Data and Material

References

- Cagno E, Micheli GJL, Jacinto C, Masi D. An interpretive model of occupational safety performance for Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises. Int J Ind Ergon. 2014 Jan 1;44(1):60–74. [CrossRef]

- Scarselli A, Corfiati M, Di Marzio D, Iavicoli S. Evaluation of workplace exposure to respirable crystalline silica in Italy. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2014. [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Working group on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans: Silica, some silicates, coal dust and para-aramid fibrils. Lyon, 15-22 October 1996. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog risks to humans. 1997 [cited 2020 Mar 3];68:1–475. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9303953.

- International Labour Organization. World Statistics: The enormous burden of poor working conditions. 2020 [cited 2023 Jan 22]. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/moscow/areas-of-work/occupational-safety-and-health/WCMS_249278/lang--en/index.htm#:~:text=The enormous burden of poor working conditions&text=Worldwide%2C there are around 340,of accidents and ill health.

- Department of Mineral Resources. 2019 Mine Health and Safety Statistics | South African Government. 2020 [cited 2023 Jan 22]. Available online: https://www.gov.za/speeches/2019-mine-heatlh-and-safety-statistics-24-jan-2020-0000.

- Zambian Parliament. The Occupational Health and Safety Act No. 36 of 2010. 2010;(36):53–66. Available online: http://www.parliament.gov.zm/node/3409.

- Government of the Republic of Zambia. The Workers’ Compesation ACT Chapter 271 of the Laws of Zambia. 2010.

- Nguyen V, Thu HNT, Le Thi H, Ngoc AN, Van DK, Thi QP, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) on silicosis among high-risk worker population in five provinces in Vietnam. In: Xuan-Nam Bui, Changwoo Lee CD, editor. Proceedings of the international conference on innovations for sustainable and responsible mining. Hanoi, Vietnam: Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH; 2021 [cited 2022 Nov 11]. p. 469–84. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-60839-2_25. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being. 2023 [cited 2023 Jan 23]. p. 61–78. Available online: https://zambia.un.org/en/sdgs/3.

- Scarselli A, Binazzi A, Forastiere F, Cavariani F, Marinaccio A. Industry and job-specific mortality after occupational exposure to silica dust. Occup Med (Chic Ill). 2011 Sep 1;61(6):422–9. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/occmed/kqr060. [CrossRef]

- Arrandale VH, Kalenge S, Demers PA. Silica exposure in a mining exploration operation. Arch Environ Occup Heal. 2018 Nov 2;73(6):351–4. [CrossRef]

- Kim HR, Kim B, Jo BS, Lee JW. Silica exposure and work-relatedness evaluation for occupational cancer in Korea. Vol. 30, Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2018 [cited 2020 Sep 18]. Available online: /pmc/articles/PMC5791359/?report=abstract. [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Zambia Mining Investment and Governance Review. Zambia Mining Investment and Governance Review. World Bank; 2016. Available online: http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/book/10.1596/24317. [CrossRef]

- Ahadzi DF. Awareness of adverse health effects of silica dust exposure among stone quarry workers in Ghana. 2021;0171119931(February):1–41. [CrossRef]

- Aluko OO, Adebayo AE, Adebisi TF, Ewegbemi MK, Abidoye AT, Popoola BF. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of occupational hazards and safety practices in Nigerian healthcare workers. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1). [CrossRef]

- Mavhunga K. Knowledge, attitude and practice of coal mineworkers pertaining to Occupational Health and Safety at the Leeuwpan Mine in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. 2018. Available online: http://univendspace.univen.ac.za/handle/11602/1183.

- You M, Li S, Li D, Xia Q. Study on the Influencing Factors of Miners’ Unsafe Behavior Propagation. Front Psychol. 2019;10(November):1–12. [CrossRef]

- Takemura Y, Kishimoto T, Takigawa T, Kojima S, Wang BL, Sakano N, et al. Effects of mask fitness and worker education on the prevention of occupational dust exposure. Acta Med Okayama [Internet]. 2008;62(2):75–82. Available online: https://www.ptonline.com/articles/how-to-get-better-mfi-results.

- Haas EJ, Willmer D, Cecala AB. Formative research to reduce mine worker respirable silica dust exposure: A feasibility study to integrate technology into behavioral interventions. Pilot Feasibility Study. 2016;2(1):1–11. [CrossRef]

- Sunandar S, Yodang Y. Analysis of Mining Engineering Students’ Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices on Occupational Safety and Health in Mining Industry Field. J Aisyah J Ilmu Kesehat. 2021;6(1):127–32. [CrossRef]

- Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Heal Educ Behav. 1984;11(1):1–47. [CrossRef]

- Guerin RJ, Sleet DA. Using Behavioral Theory to Enhance Occupational Safety and Health: Applications to Health Care Workers. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15(3):269–78. [CrossRef]

- Prochaska J, Diclemente CC, Norcross JC. How people change, Prochaska, 1992. Am Psychol. 1992;47(Septembe9):1102–14. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1329589/. [CrossRef]

- Kyaw WM, Chow A, Hein AA, Lee LT, Leo YS, Ho HJ. Factors influencing seasonal influenza vaccination uptake among health care workers in an adult tertiary care hospital in Singapore: A cross-sectional survey. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47(2):133–8. [CrossRef]

- Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399–418. [CrossRef]

- Kim SA, Oh HS, Suh YO, Seo WS. An integrative model of workplace self-protective behavior for Korean nurses. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2014;8(2):91–8. [CrossRef]

- DeJoy DM. Theoretical models of health behavior and workplace self-protective behavior. J Safety Res. 1996;27(2):61–72. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Disabil CBR Incl Dev. 1991;33(1):52–68.

- Guerin RJ, Toland MD. An application of a modified theory of planned behavior model to investigate adolescents’ job safety knowledge, norms, attitude and intention to enact workplace safety and health skills. J Safety Res. 2020;72(December):189–98. [CrossRef]

- Hill RJ. Contemporary Sociology,. 2015;6(2):244–5.

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Attitudes and the AttitudeBehavior Relation: Reasoned and Automatic Processes. Eur Rev. 2007;(770853977):37–41. [CrossRef]

- Hogg MA, Vaughan GM. Social psychology. New York: Pearson Education Limites; 2005.

- Haddock G, Maio GR. Attitudes: Content, Structure and Functions. Introd to Soc Psychol a Eur Perspect [Internet]. 2008;112–33. Available online: http://www.blackwellpublishing.co.uk/content/hewstonesocialpsychology/chapters/chapter6.pdf.

- Cherry K. Attitudes and Behavior in Psychology. Very Well Mind. 2021;1–7. Available online: https://www.verywellmind.com/attitudes-how-they-form-change-shape-behavior-2795897.

- Tinbergen N. The study of instinct. 1951.

- Alder H. Representational Systems. In: Handbook of NLP. 2019. p. 99–113.

- Shull RL. Interpreting Cognitive Phenomena: Review of Donahoe and Palmer’s Learning And Complex Behavior 1. J Exp Anal Behav. 1995;63(3):347–58. [CrossRef]

- Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ. Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55(1974):591–621. [CrossRef]

- Zin SM, Ismail F. Employers’ Behavioural Safety Compliance Factors toward Occupational, Safety and Health Improvement in the Construction Industry. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci. 2012;36(June 2011):742–51. [CrossRef]

- Likert R. A Technique for the Measurment of Attitudes. WoodsWorth, editor. Vol. 140. New York: Archives of Psychology; 1932.

- Boone HN, Boone DA. Analyzing Likert data. J Ext. 2012;50(2). [CrossRef]

- Beth AA. Assessment of occupational safety compliance in small-scale gold mines in siaya county, kenya. 2018;1–90. Available online: http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/11295/104630/Beth_Assessment Of Occupational Safety Compliance In Small-Scale Gold Mines In Siaya County%2C Kenya..pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

| Variable | Work area | Mean for Individual Items (Range) | Overall Mean Score | Overall Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | All | 3.31-3.59 | 3.50 | 1.14 |

| Underground | 3.31-3.59 | 3.58 | 1.13 | |

| Surface | 3.43-4.49 | 3.39 | 1.15 | |

| Attitudes | All | 3.37-3.80 | 3.71 | 1.15 |

| Underground | 3.72-3.80 | 3.76 | 1.01 | |

| Surface | 3.37-3.70 | 3.60 | 1.15 | |

| Work behaviour and practice | All | 3.29-3.64 | 3.50 | 1.16 |

| Underground | 3.49-3.64 | 3.59 | 1.20 | |

| Surface | 3.29-3.41 | 3.38 | 1.09 | |

| Compliance with safety standards | All | 3.41-3.64 | 3.53 | 1.06 |

| Underground | 3.31-3.64 | 3.57 | 1.09 | |

| Surface | 3.41-3.49 | 3.47 | 1.03 | |

| Exposure to respirable dust | All | 3.20-3.57 | 3.38 | 0.96 |

| Underground | 3.45-3.57 | 3.48 | 0.92 | |

| Surface | 3.20-3.42 | 3.22 | 0.99 |

| Attitudes | Behavioural Practice | Compliance and Safety Standards | Exposure to Respirable Dust | Knowledgeability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | 0.865 | ||||

| Work Behaviour and Practice | 0.778 | 0.845 | |||

| Compliance and Safety Standards | 0.751 | 0.835 | 0.831 | ||

| Exposure to Respirable Dust | 0.325 | 0.391 | 0.391 | 0.806 | |

| Knowledge | 0.828 | 0.724 | 0.688 | 0.326 | 0.843 |

| VIF | |

|---|---|

| Attitudes | 3.238 |

| Work Behaviour and Practice | 2.839 |

| Compliance and Safety Standards | 2.849 |

| Exposure to Respirable Dust | 2.227 |

| Knowledge | 2.958 |

| Sample mean (M) | Standard deviation (STDEV) | t-statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge -> Exposure to Respirable Dust | 0.085 | 0.079 | 1.103 | 0.27 |

| Knowledge -> Attitudes | 0.828 | 0.015 | 54.139 | 0.00 |

| Knowledge -> Work Behaviour and Practice | 0.723 | 0.026 | 27.627 | 0.00 |

| Knowledge -> Compliance and Safety Standards | 0.688 | 0.027 | 25.61 | 0.00 |

| Attitudes -> Exposure to Respirable Dust | -0.058 | 0.079 | 0.751 | 0.453 |

| Work Behaviour and Practice -> Exposure to Respirable Dust | 0.2 | 0.083 | 2.407 | 0.016 |

| Compliance and Safety Standards -> Exposure to Respirable Dust | 0.211 | 0.086 | 2.429 | 0.015 |

| Hypotheses | Remark | |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Knowledge of the risks and dangers of respirable dust positively reduces exposure to respirable dust in workers | Not Supported |

| H2 | Knowledge of the risks and dangers of respirable dust is positively moderated by attitudes to reduce respirable dust exposure in workers. | Not Supported |

| H3 | Knowledge of the risks and dangers of respirable dust is positively moderated by work behaviour and practice towards respirable dust exposure | Supported |

| H4 | Knowledge of the risks and dangers of respirable dust is positively moderated by compliance with safety standards towards respirable dust exposure | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).