1. Introduction

The current morphological criteria for histological diagnosis of cervical lesions are based on the WHO 2014 classification [

1]. Within the context of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), a distinction is necessary between moderate-grade lesions (moderate dysplasia/CIN2) and more severe lesions (severe dysplasia, carcinoma in situ/CIN3) [

2,

3]. The recommended treatment is excisional treatment, specifically conization, in which the pathological tissue is removed for subsequent histological examination. Conization allows for the removal of all visible pathological tissue observed during colposcopy and serves both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. The excised tissue includes the exocervix and endocervix and is shaped like a cone/cylinder with an endocervical apex. Various techniques can be employed for the excision, such as cold knife, laser, loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), and large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) [

4,

5]. Currently, generators capable of emitting high-frequency alternating currents (400 KHz-4 MHz) at low voltage are used, with variable power ranging from 100 to 400W. The active electrodes employed are loop-shaped (

Figure 1) and can have different configurations (circular, rectangular, square) with diameters and depths ranging from 0.5 to 2 cm [

6].

The diameter of the wire, made of steel and tungsten, does not exceed 0.2 mm. This characteristic allows for a high density of current to pass through it, resulting in the vaporization of the tissue proximally to the wire due to the high temperature produced on a very small surface area. The loop is slowly inserted into the cervix to achieve the excision of a roughly conical-shaped sample [

7]. Immediate complications may include intraoperative bleeding (4.2-7.9%) and postoperative bleeding (0.4-2.6%), postoperative infections (0.3-3.5%), and damage to adjacent organs (0.06-0.5%) [

8,

9]. Late complications include cervical canal stenosis, which can cause dysmenorrhea and hematometra in fertile patients, or it can mask uterine bleeding in postmenopausal women, which can be an early symptom of endometrial neoplasia [

10,

11]. The excisional techniques appear to slightly worsen the obstetric outcome in subsequent pregnancies [

12,

13]. Currently, it is not known whether the treatment can cause future fertility problems or affect the course of subsequent pregnancies. Some studies have reported a modestly increased risk of miscarriage and preterm delivery directly proportional to the size of the excised cone [

14].

2. Case Report

A 34-year-old woman undergoes a screening Pap test with an H-SIL result, which prompts a counseling session regarding the significance of the high-grade lesion and further diagnostic tests. She undergoes a diagnostic colposcopy with biopsy. The histological result shows CIN 2, and a proposal for a conization procedure is made. Counseling regarding the procedure is provided, and informed consent is obtained. After preparing the surgical field, vaginal valves are placed, and colposcopy is performed in the operating room, revealing a cervical lesion that is larger than initially diagnosed. The margins are delineated, and the cone is excised using a diathermic loop. Subsequently, enlargements are necessary to ensure the complete removal of the macroscopically visible lesion. During the surgical procedures, there is significant bleeding, likely originating from the right cervical branch of the uterine artery. Hemostatic stitches are applied to the right vaginal wall to control the bleeding. The application of the stitches is successful in achieving hemostasis, as superficial stitches would have resulted in failure to contain the bleeding with potentially severe consequences for the patient. The ureter was not injured during the placement of the stitches. The histological examination classifies the lesion as CIN3, which is internationally classified as carcinoma in situ. This lesion is present in all the margins excised following the cone procedure (

Figure 2).

Morphologically, enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei, clumped chromatin, irregularities, and notches in the nuclear membrane, and altered nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio can be observed. Mitotic figures at various levels are also frequent (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3-4.

CIN3 histological sample.

Figure 3-4.

CIN3 histological sample.

The lesion was completely removed; in the small cone performed on the remaining cervical canal, therefore on the portion of the cervix that was not removed, no histological lesion is present (

Figure 5).

In the postoperative course, the patient experienced nonspecific symptoms: she remained afebrile, had mild pelvic pain at the site of the vaginal suture, which was managed with paracetamol as needed, and had diarrhea throughout the hospital stay. Only on the fifth postoperative day, malodorous secretions were observed in the vagina, and the patient was promptly examined for suspected vagino-rectal fistula. Immediate antibiotic therapy was initiated, and further diagnostic and radiologic tests confirmed the clinical suspicion of vagino-rectal fistula (

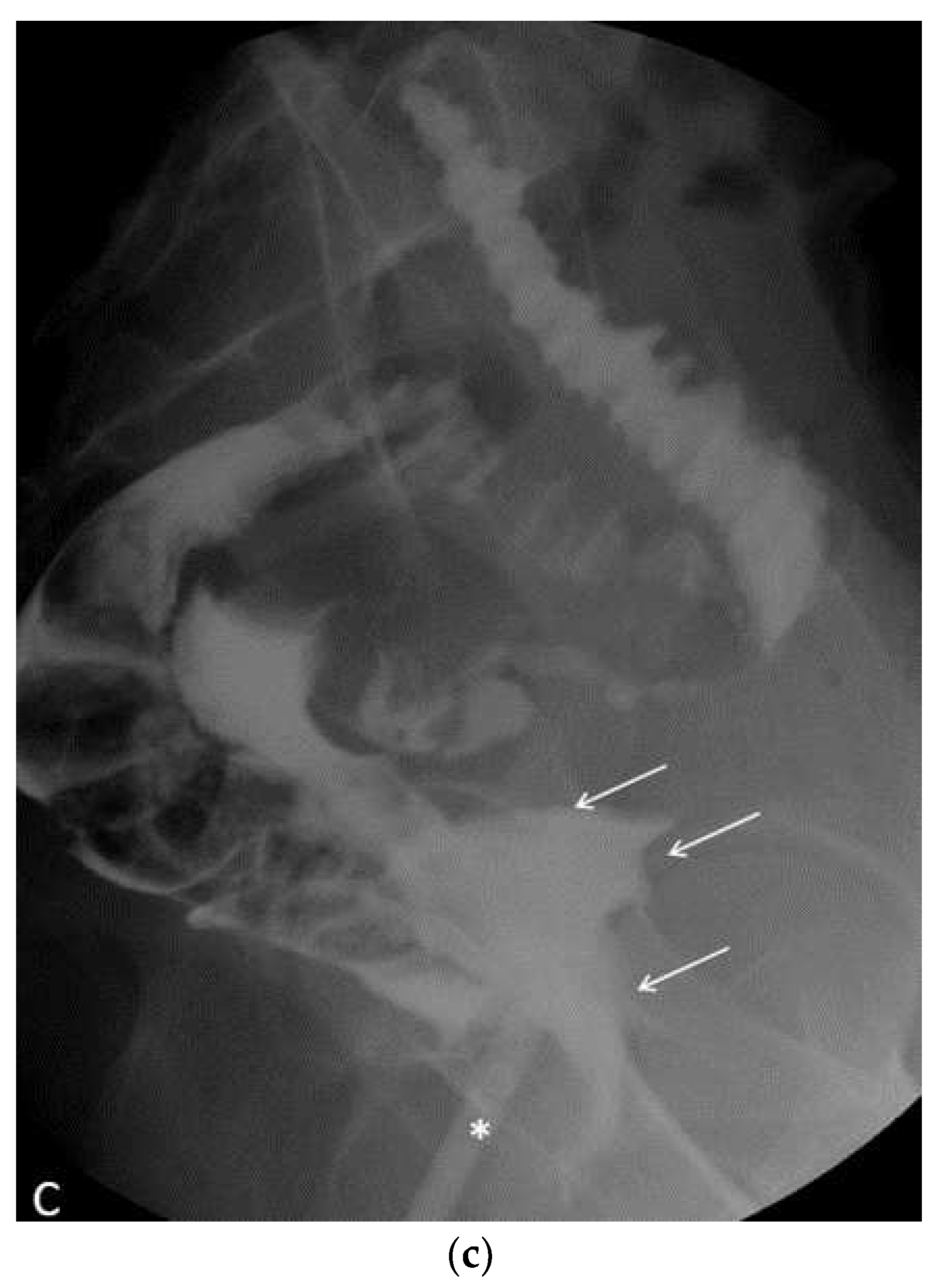

Figure 6a–c), and the patient undergone adequate surgical treatment.

3. Results and Conclusions

The biopsy performed under colposcopic guidance confirmed involvement of two-thirds of the entire thickness of the squamous epithelial lining, with a diagnosis of HSIL/CIN2. Approximately two months later, the lesion progressed, and when the patient underwent conization with a loop diathermy, the cytological abnormalities involved the full thickness of the squamous epithelium, indicating HSIL/CIN3. Conization with loop diathermy offers numerous advantages and is currently the most used excisional technique. The therapeutic success rate ranges from 90% to 97%. The excisional treatment is indicated to allow histological examination of the removed tissue, which is necessary to identify any tumors and plan the most appropriate oncological treatment. In fact, the frequency of “occult” invasive carcinomas can reach 12% of cases, primarily consisting of stage pT1A1, pT1A2, and stage 1B tumors. It should be noted that staging for stage 1A is postoperative [

15]. Postoperative bleeding is usually minor, but in this case, bleeding from the uterine cervical branch required the application of hemostatic sutures. The sutures were performed on the right vaginal wall, away from the rectum, excluding any transfixion involving the rectum and vagina. The thermal damage caused by the loop on the lateral walls of the cone is negligible (maximum thickness 50-300μ), allowing the pathologist to make a satisfactory histological evaluation. In the case of extensive lesions, the excision site can be widened. Any bleeding originating from the walls of the loss of substance created by the passage of the loop is then cauterized using a ball electrode, which also helps eliminate any glandular involvement [

16,

17,

18]. The procedure was performed with the application of vaginal valves, and therefore, the cervix and vagina were examined before, during, and after the surgery, with no areas of vaginal mucosal injury observed. The integrity of the vaginal mucosa in its entirety and the proper removal of the pathological component of the cervix indicate the correct use of loop diathermy in all stages of the procedure, both in conization and subsequent widening. The CIN3 lesion, classified as carcinoma in situ in the international literature, was completely excised by widening the margins of the lesion. The presence of HR-HPV infection and CIN has been found to be associated with changes in the vaginal microbiota and alteration of local immune function, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of preterm delivery. These factors should also be considered in surgical procedures, as they can cause anatomical and functional damage to the cervix [

19,

20]. Inappropriate excisional treatment and subsequent difficult diagnosis due to poorly identifiable margins can mask an invasive lesion and, in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, lead to hysterectomy even in young women [

21].

In conclusion, the clinical therapeutic pathway and subsequent surgical treatment can be considered appropriate. The lesion was present in all the enlargements, without which complete removal of the lesion would not have been achieved. The thermal damage is not considered a direct cause of the rectovaginal fistula, but it is likely an indirect cause due to HPV-related dysplasia associated with immune defenses alteration, as well as from dysentery, which can disrupt intestinal metabolism and lower its immune defenses, creating an inflammatory state that weakens tissue walls.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.I., S.I., L.I. and C.D.I.; methodology, S.I. and C.D.I.; validation, L.I. and P.I.; formal analysis, P.M., T.S., M.M. and R.P.; resources and data curation, R.B. and C.V.; writing—original draft preparation and review, P.M.; supervision, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Local Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available asking to the corresponding author under reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO Classication of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs. 2014. IARC, Lyon.

- Società Italiana di colposcopia e patologia cervico vaginale ”Raccomandazioni SICPCV 2019” (2019).

- Bhatha N, Berek J, Fredes M, et al. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019;145:129-135.

- Singer A, Monaghan JM. La Gestione delle Lesioni Precancerose Cervicali. In: Lesioni precancerose del basso tratto genitale femminile. Colposcopia, patologia e trattamento. CIC Edizioni Internazionali 1996: 111-54.

- Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J, Ronco G, Schenck U, Segnan N, Wiener HG, Herbert A, Daniel J, Karsa L von (eds). European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening – Second edition. European Commission/IARC, Luxembourg 2008 – XXXII ISBN 978-92-79-07698-5. Available online: http://bookshop.europa.eu.

- HPV-correlata Riv. It. Ost. Gin. - 2008 - Num. 19 Sp.

- Documento GISCi “Manuale del II livello” (2010).

- Santesso N, Mustafa R. Wiercioch W, et al. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of bene ts and harms of cryotherapy, LEEP, and cold knife conization to treat cer- vical intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016;132:266-271. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Hirsch P, Keep S, Bryant A. Interventions for preventing blood loss during the treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;16:CD001421. [CrossRef]

- Sopracordevole F. CIN: trattamento con laser CO2. In: Chirurgia ambulatoriale e day surgery. Piccoli R e Boselli F Editori, Mediacom Ed, Casinalbo, 2006 p 133-38.

- Kiuchi K, Hasegawa K, Motegi E, Kosaka N, Udagawa Y, Fukasawa I. Complications of laser conization versus loop electrosurgical excision procedure in pre- and postmenopausal patients. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2016;37(6):803-808. [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa K, Torii Y, Kato R, Udagawa Y, Fukasawa I. The problems of cervical conization for postmenopausal patients. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2016;37(3):327-31. [CrossRef]

- Liverani CA et al. Conizzazione e rischio di parto pretermine. La Colposcopia in Italia 2011;XXIV(1):11-14. 1.

- Kyrgiou M, Athanasiou A, Paraskevaidi M, et al. Adverse obstetric outcomes af-ter local treatment for cervical preinvasive and early invasive disease according to cone depth: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2016;28:i3633. [CrossRef]

- Wright JD et al. Fertility conserving surgery for young women with stage IA1 cervical cancer: safety and access. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115(3):585-90. [CrossRef]

- Monaghan JM. Laser Vaporization and excisional techniques in the treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Bailliere’s Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1995; 9(1): 173-87. [CrossRef]

- Prendiville W. Large loop excision of the transformation zone. Bailliere’s Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1995; 9 (1): 189-220. 1.

- Boselli F. CIN e condilomatosi cervicale. Trattamento con elettrochirurgia a radiofrequenza. In: Piccoli R, Boselli F. Chirurgia Ginecologica Ambulatoriale

e Day Surgery. Mediacom ed. 2006: 123-31.

- Maina G, Ribaldone R, Danese S, et al. Obstetric outcomes in patients who have undergone excisional treatment for high-grade cervical squamous intra-epithelial neoplasia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019;236:210-213. [CrossRef]

- Reilly R, Paranjothy S, Beer H, et al. Birth outcomes following treatment for pre- cancerous changes to the cervix: a population-based record linkage study. BJOG 2012;119:236-244. [CrossRef]

- Sopracordevole F, Canzonieri V, Giorda G, De Piero G, Lucia E, Campagnutta E. Conservative treatment of microinvasive adenocarcinoma of uterine cervix: long-term follow-up. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012 Oct;16(4):381-6. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).