Submitted:

12 July 2023

Posted:

13 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical framework

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Demographic potential

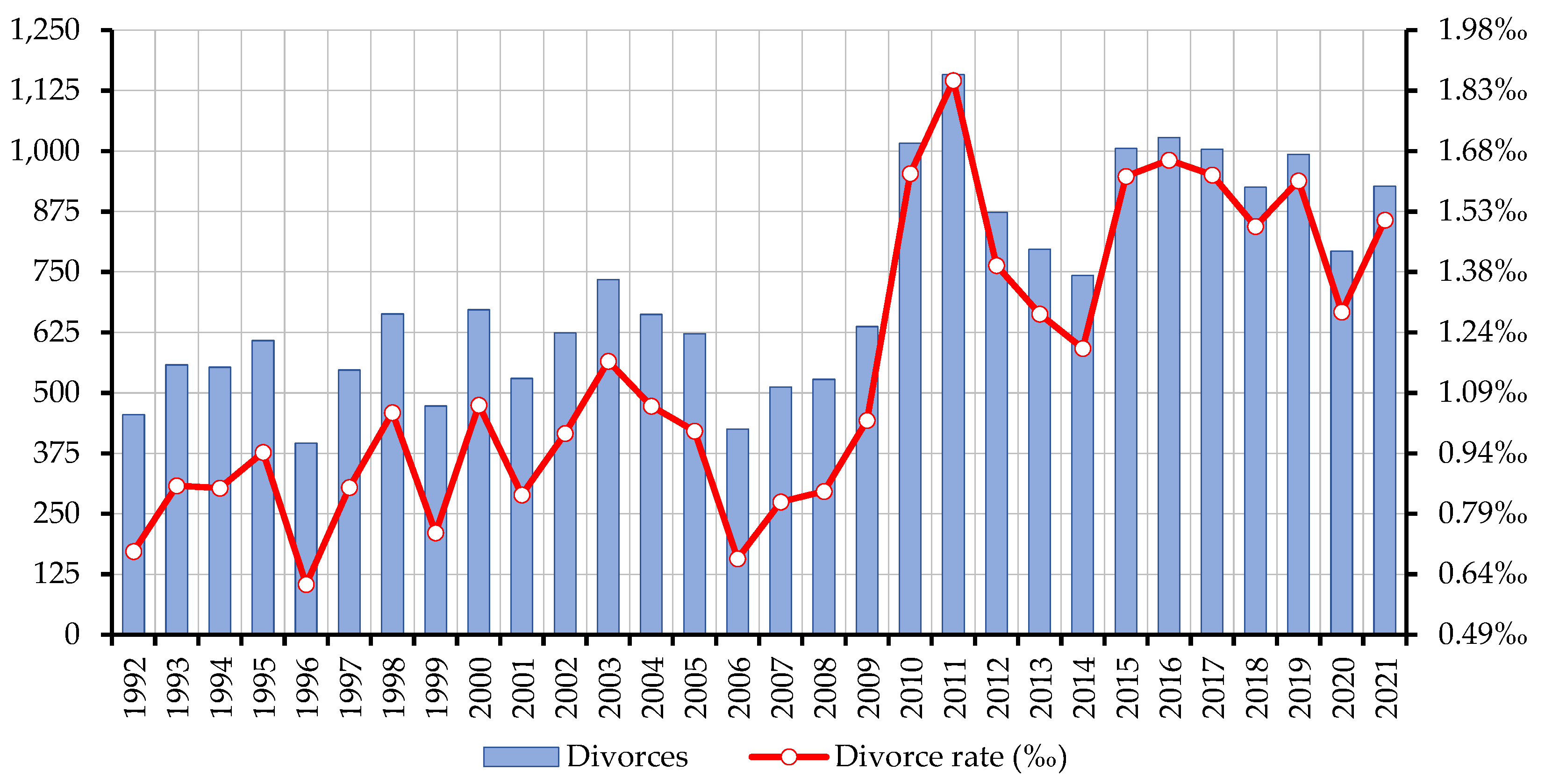

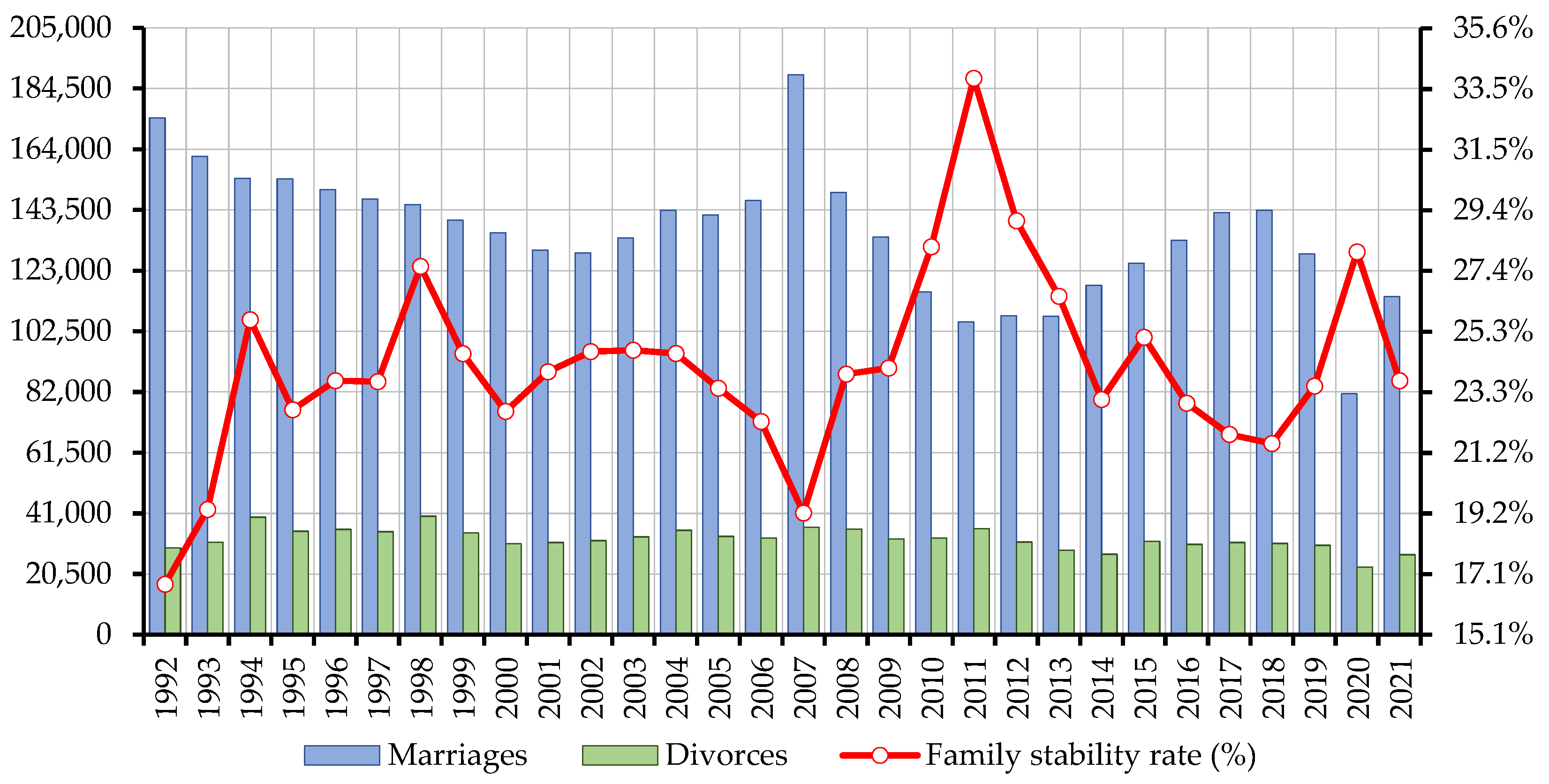

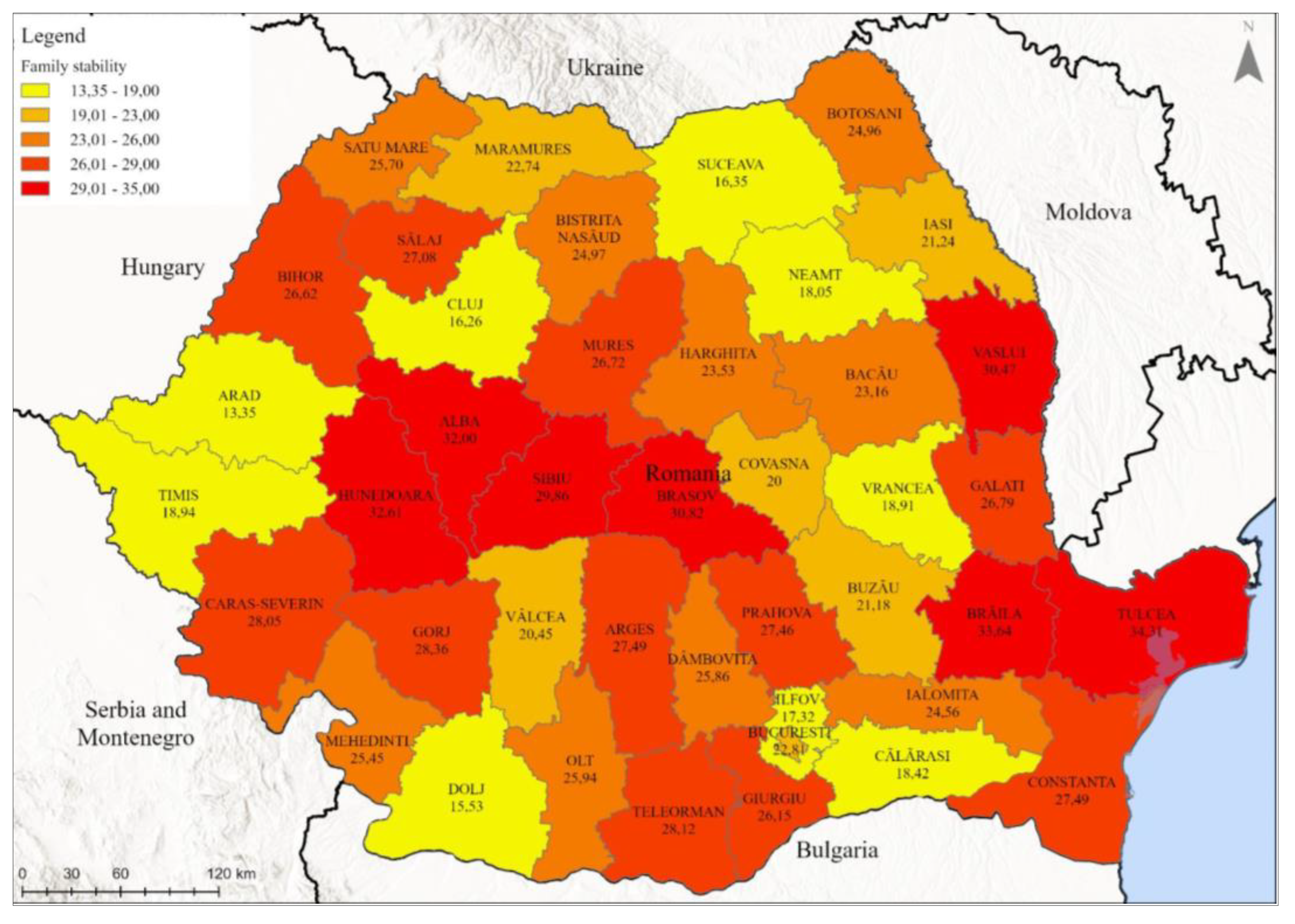

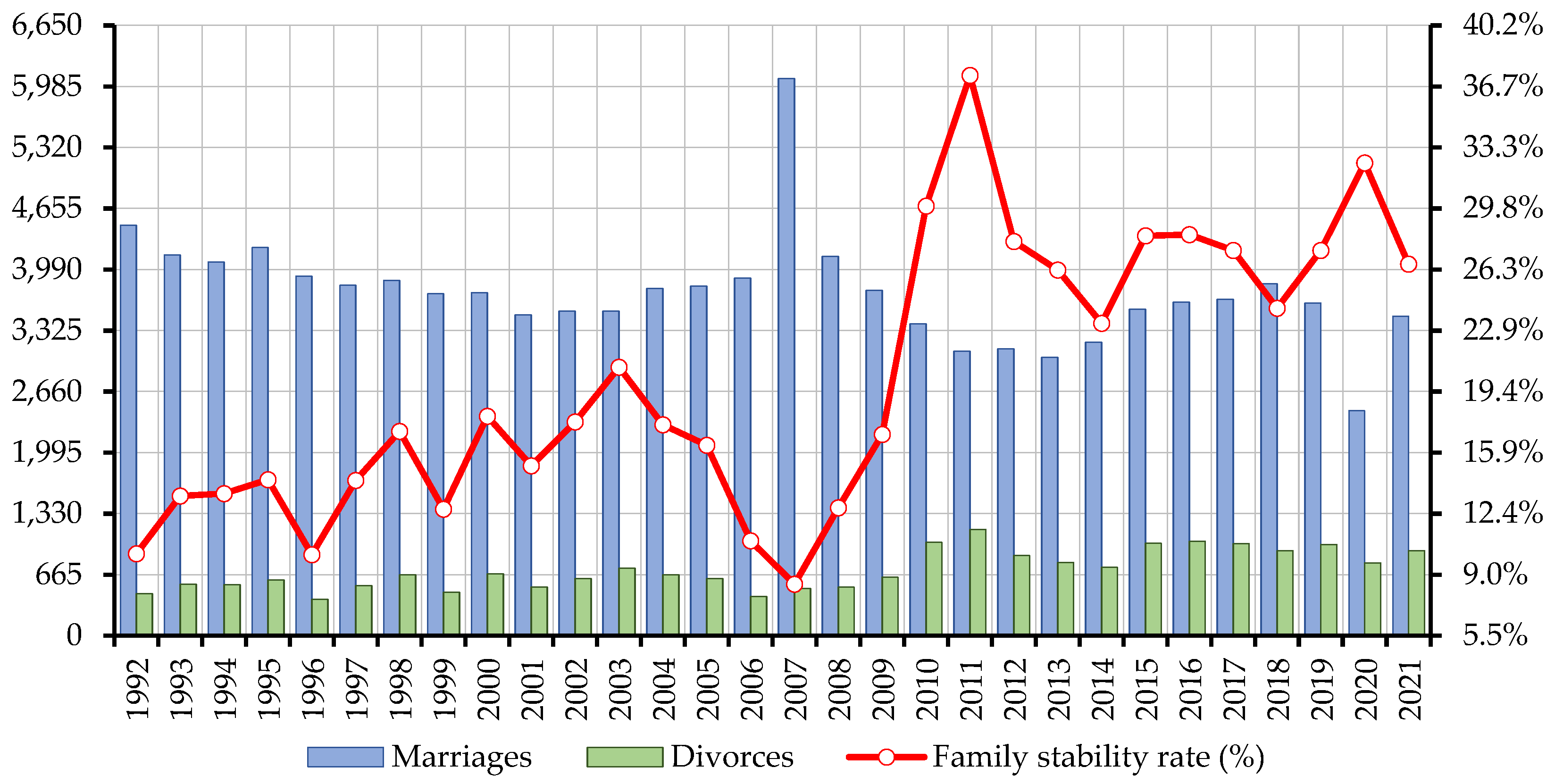

4.2. Familial Stability/Instability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Justice Decree No 770/1966, Anti-Abortion Decree; 1966.

- Bolovan, I. Aspecte privind relaţia politică-demografie în timpul regimului comunist din România / Aspects regarding the political-demographic relationship during the communist regime in Romania. Arhiva Someşană 2004, 3, 285–294.

- Anton, L. La Mémoire de l’avortement En Roumanie Communiste : Une Ethnographie Des Formes de La Mémoire Du Pronatalisme. Roumain. Thesis, for PhD, Université ”Victor Segalen”, Bordeaux II / Université de Bucarest: Bordeaux / Bucharest, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jinga, L.; Soare, F.; Doboș, C.; Roman, C. Politica pronatalistă a regimului Ceaușescu. Vol. II: Instituții și practici / The pro-natalist policy of the Ceaușescu regime. Vol II: Institutions and Practices; Editura Polirom: Iași, 2011; ISBN 978-973-46-2014-2. [Google Scholar]

- Coman, O. Gardienii Decretului. Lumea ascunsă a represiunii împotriva avorturilor / Guardians of the Decree. The hidden world of abortion repression Available online: https://beta.dela0.ro/gardienii-decretului-lumea-ascunsa-a-represiunii-impotriva-avorturilor/.

- Miron, O. Politica Pronatalistă În România Comunistă, o Cale de Control al Vieții Private / Pro-Natalist Politics in Communist Romania, a Way of Controlling Private Life. Polis. Revista de Științe Politice 2021, IX.

- Ianoș, I.; Guran, L. Comportamentul demografic recent al orașelor României / The recent demographic behavior of Romanian cities. SCG 1995, XLII, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, W.S. Population. The American Journal of Sociology 1929, 34, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibenstein, H. A Theory of Economic-Demographic Development; Princeton University Press: Princeton, 1954; ISBN 978-0-8371-1046-2. [Google Scholar]

- Geddes, J.; Muir, K. Aspects of Social Geography: Change and Development; Edward Arnold: London, 1978; ISBN 978-0-7131-7614-8. [Google Scholar]

- Trebici, V. Populația terrei: demografie mondială / Population of the Earth: World Demography; Editura Științifică: București, 1991; ISBN 978-973-44-0061-4. [Google Scholar]

- Trebici, V. Populația României și creșterea economică. Studii de demografie economică / Romania’s population and economic growth。Studies of economic demography; Editura Politică, 1971. 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Trebici, V. Genocid și demografie / Genocide and demography; Editura Humanitas, 1991; ISBN 978-973-28-0218-2.

- Trebici, V. Demografie / Demography; Editura Enciclopedică, 1996; ISBN 978-973-45-0159-5.

- Rotariu, T. Demografie și sociologia populației. Fenomene demografice / Population demography and sociology. Demographic phenomena; Editura Polirom: Iași, 2003; ISBN 978-973-681-409-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rotariu, T. Demografie şi sociologia populaţiei. Structuri şi procese demografice / Population demography and sociology. Demographic structures and processes; Editura Polirom: Iași, 2009; ISBN 978-973-46-1250-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rotariu, T. Studii demografice / Demographic studies; Editura Polirom: Iași, 2010; ISBN 978-973-46-1701-2. [Google Scholar]

- Rotariu, T.; Dumănescu, L.; Hărăguş, M. Demografia României în perioada postbelică (1948-2015) / Demography of Romania in the post-war period (1948-2015); Editura Polirom: Iași, 2017; ISBN 978-973-46-6865-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cucu-Oancea, O. Disparităţi privind comportamentele demografice ale populaţei rurale din România / Disparities regarding the demographic behaviors of the rural population in Romania. Revista Română de Sociologie 2005, 16, 481–501.

- Ghețău, V. Tranziție și demografie / Transition and demography. Populație & Societate. Periodic al Centrului de Cercetari Demografice Vladimir Trebici 1997, 1.

- Ghețău, V. Situația demografică a României: stadiu actual, factori de influență și perspective / The demographic situation of Romania: current state, influencing factors and perspectives; Caietele sesiunilor de dezbatere a Strategiei de dezvoltare durabilã a României „Orizont-2025”; București, 2004.

- Ghețău, V. Declinul demografic și viitorul populației României - o perspectivă din 2007 asupra populației României din secolul 21 / Demographic decline and the future of Romania’s population - a 2007 perspective on Romania’s population in the 21st century; Institutul Național de Cercetări Economice, Centrul de Cercetari Demografice „Vladimir Trebici”: Buzău, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sandu, D. Migrația temporară în străinătate / Temporary migration abroad. In Demografia României; Editura Academiei Române: București, 2018 ISBN 978-973-27-3504-6.

- Ilieș, A. Etnie, confesiune și comportament electoral în Crișana și Maramureș (Sfârșitul sec. IX și sec. XX). Studiu geografic / Ethnicity, confession and electoral behavior in Crișana and Maramureș (End of the 9th and 20th centuries). Geographical study; Editura Dacia: Cluj-Napoca, 1997; ISBN 973-35-0782-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ilieș, A.; Stașac, M. Studiul geografic al populației / Geographical study of population; Editura Universității din Oradea: Oradea, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Litrã, A.V. Evoluția Demograficã a României – Convergențã Sau Periferizare? / The Demographic Evolution of Romania - Convergence or Peripheralization? Theoretical and Applied Economics 2006, 2, 93–100.

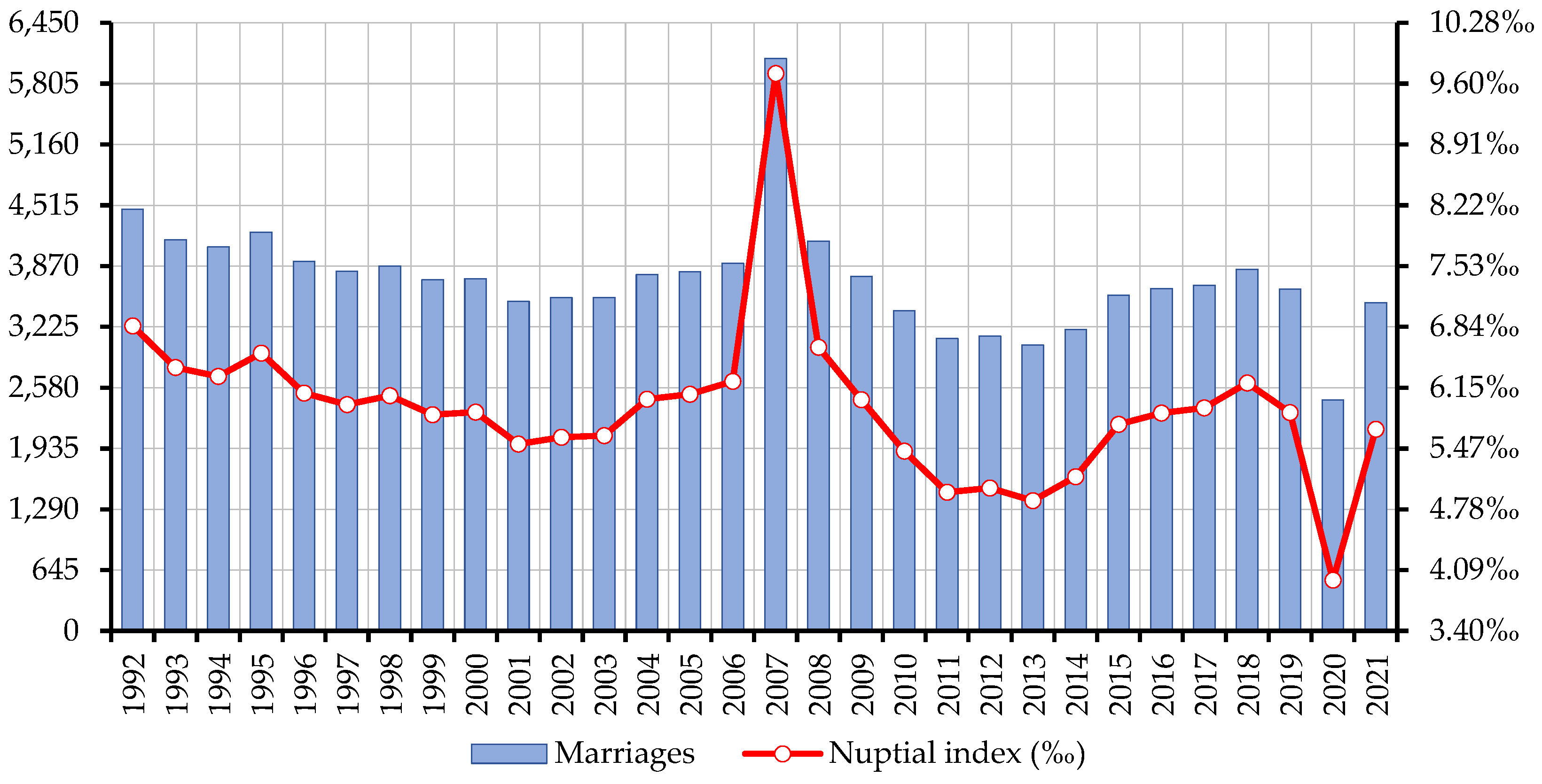

- Stupariu, I.M.; Josan, I. Aspecte Privind Nupţialitatea Şi Divorţialitatea În România / Aspects Regarding Nuptiality and Divorce in Romania. Analele Universităţii din Oradea. Seria Geografie 2006, 16, 86–93.

- Stașac, M.; Bucur, L. Geo-Demographical Changes in Rural Space of Oradea Metropolitan Area. Analele Universității din Oradea. Seria Geografie 2010, 20, 223–232.

- Drăgan, M. Aspecte ale comportamentului demografic în Munţii Apuseni / Aspects of demographic behavior in the Apuseni Mountains. Geographia Napocensis 2013, VII, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Filimon, C. Depresiunea Oradea-Bratca: studiu de populaţie şi de aşezări / The Oradea-Bratca depression: population and settlement study; Presa Universitară Clujeană: Cluj-Napoca, 2014; ISBN 978-973-595-717-9. [Google Scholar]

- Stupariu, I.M. Municipiul Oradea. Studiu de Geografie Umană / Oradea municipality. Study of Human Geography; Editura Universității din Oradea: Oradea, 2014; ISBN 978-606-10-1355-5. [Google Scholar]

- Guran-Nica, L. Aspects of the Demographic Crisis in Romania. Studii și Cercetări de Antropologie 2015, 5, 61–71.

- Linc, R.; Dinca, I.; Stașac, M.; Tătar, C.F.; Bucur, L. Surveying the Importance of Population and Its Demographic Profile, Responsible for the Evolution of the Natura 2000 Sites of Bihor County, Romania. Eastern European Countryside 2017, 23, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropa, M. Depresiunea Beiușului. Studiu de geografia populației / Beișului depression. Population geography study; Editura Risoprint: Cluj-Napoca, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Deac, L.A.; Herman, G.V.; Gozner, M.; Bulz, G.C.; Boc, E. Relationship between Population and Ethno-Cultural Heritage - Case Study: Crișana, Romania. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tătar, C.F.; Dinca, I.; Linc, R.; Stupariu, I.M.; Bucur, L.; Stașac, M.; Nistor, S. Oradea Metropolitan Area as a Space of Interspecific Relations Triggered by Physical and Potential Tourist Activities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, J. Riscurile Umane / Human Risks. Riscuri şi catastrofe 2002, 1, 43–54.

- Surd, V.; Puiu, V.; Zotic, V.; Moldovan, C. Riscul demografic in Muntii Apuseni / The demographic risk in the Apuseni Mountains; Presa Universitară Clujeană: Cluj-Napoca, 2007; ISBN 978-973-610-626-2. [Google Scholar]

- Muntele, I. Les Risques Géo-Démographiques En Roumanie. Réalités et Perspectives. Lucrările seminarului geografic „Dimitrie Cantemir” 2009, 30, 73–85.

- National Institute for Statistics of Romania Baze de Date Statistice - Tempo Online Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table.

- Bulgaru, M.; Bulgaru, O. Modalități de Constituire a Cuplurilor Familiale: Consecințe Demografice / Ways of Establishing Family Couples: Demographic Consequences. Studia Universitatis Moldaviae 2020, 133, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Statistics of Romania Evoluţia Natalităţii Şi Fertilităţii În România (Evolution of Birth Rate and Fertility in Romania); National Institute for Statistics of Romania: București, 2012.

- Parlamentul României Legea, Nr. 396 Din 30 Octombrie 2006 Privind Acordarea Unui Sprijin Financiar La Constitui-Rea Familiei / Law No. 396 of October 30, 2006 Concerning the Granting of Financial Support to the Establishment of the Family; Parlamentul României: București, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Härkönen, J.; Billingsley, S.; Hornung, M. Divorce Trends in Seven Countries over the Long Transition from State Socialism: 1981-2004. In Divorce in Europe. New Insights in Trends, Causes and Consequences of Relation Break-Ups; Mortelmans, D., Ed.; European Studies of Population; Springer, 2000; Vol. 21, pp. 63–89 ISBN 1381-3579.

- Baetica, R. Nupţialitatea şi natalitatea în România / Marriage and birth rate in Romania; Statistic Explained; Eurostats: București, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dalkhat, E. Application of the Demographic Potential Concept to Understanding the Russian Population History and Prospects: 1897-2100. Demographic Research 2001, 4, 289–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmijn, M. Explaining Cross-National Differences in Marriage, Cohabitation, and Divorce in Europe, 1990-2000. Population Studies. A Journal of Demography 2007, 61, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swianiewicz, P. Municipal Divorces ꟷ The Under-Researched Topic of Territorial Reforms. Acta Geobalcanica 2020, 6, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A.; Schmidheiny, K. The Intergenerational Transmission of Divorce: A Fifteen-Country Study with the Fertility and Family Survey. Comparative Sociology 2013, 12, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hărăguş, M. From Cohabitation to Marriage When a Child Is on the Way. A Comparison of Three Former Socialist Countries: Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 2015, 46, 329–350. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).