I. Introduction

Corporate bond liquidity has been a matter of discussion for many years.(Aramonte & Avalos, 2020) While the research on India’s equity markets is extensive, research on the country’s secondary corporate bond markets is limited. India has a top-notch equity market that is growing significantly, but its bond market has lagged behind globally. (Schou-Zibell & Wells, 2008). To meet the needs of its firms and investors, the bond market must therefore evolve. (Schou-Zibell & Wells, 2008).Despite repeated attempts in the past, India’s corporate bond market expansion remains unsatisfactory (Acharya,2020). There are numerous reasons why investigating secondary corporate bonds is intriguing. When the equity market is volatile, the investment provides a non- dependable stream of funds. However, investors acquire bonds for the straightforward reason that they offer a fixed income. Interest on bonds is typically paid twice yearly and investing in bonds ensures security of money while generation of income, due to the fact that bondholders are entitled to a full repayment of the principal amount if the bonds are held until maturity(Saadaoui et al., 2022). If bonds are not held until maturity, it is difficult for investors to exit the bond market. Corporate bonds do not trade very much, especially relative to equities.(Alexander et al., 2000).Even the traded prices and volumes are not readily available and significant aspects can only be analyzed based on quotes from individual dealers which may not be accurate. (Friewald et al., 2010). As a result, bond market is susceptible to periodic illiquidity (O’Hara & Zhou, 2022). Illiquidity in bond markets is not limited to one country, but it is present even in African & other bond markets (Eke et al., 2020), (Schou-Zibell & Wells, 2008).Several studies shown that illiquidity of bonds increases at the time of crises. This illiquidity often increases during crisis dramatically happened during subprime crises. (Dick-Nielsen et al., 2012), (Pan & Wang, 2011) with Covid 19 not an exception. Liquidity in corporate bond markets has remained weak, particularly during times of crisis. The shock caused by the Covid-19 outbreak has offered additional evidence of such vulnerability (Aramonte & Avalos, 2020). Our research aims to draw attention to the bond market’s illiquidity and provide investors a remedy in the shape of an exit strategy through security fungibility. Bond market is fully fungible as highlighted in the paper (Miller & Puthenpurackal, 2005). Liquidity assess the ease with which investors can realize the value in securities, as well as some of the transaction expenses.(Acharya, 2020) which means liquidity is the ability to promptly swap a security for a certain sum of money (in cash), whereas fungibility is the capacity to exchange an item for something of equal worth (in another asset). The main distinction between liquidity and fungibility is that liquidity returns money while fungibility returns another asset. In order to offer investors with an exit plan for illiquid bonds, this study investigates the possible benefits of bond fungibility.

To achieve the study’s objectives, the following research questions were employed

Q1. What is the solution to enhance liquidity in corporate bond market?

Q2. What is the fair value of an illiquid bond?

In this paper, an attempt has been made to answer the above questions. The subsequent sections are structured as follows. Before we discuss the solution to illiquidity, we must understand and discuss how liquidity in bond market is measured. Many measures have been proposed to approximate the amount to which a bond is liquid or illiquid by various researchers. Direct liquidity measurements (based on transaction data) are sometimes difficult to obtain for corporate bonds, where most transactions occur on the over-the-counter market. As a result, researchers used indirect measurements (’proxies’) based on bond attributes.(Houweling et al., 2005). Proxies of liquidity and the factors affecting liquidity is highlighted through literature review in Section II. Section III presents the research methodology while Section IV describes the findings, Section V proposes the solution to the problem of bond market illiquidity through a mathematical model named as “RR Fungible Model”. Section VI concludes, discusses the limitations and directions for future research.

II. Literature review

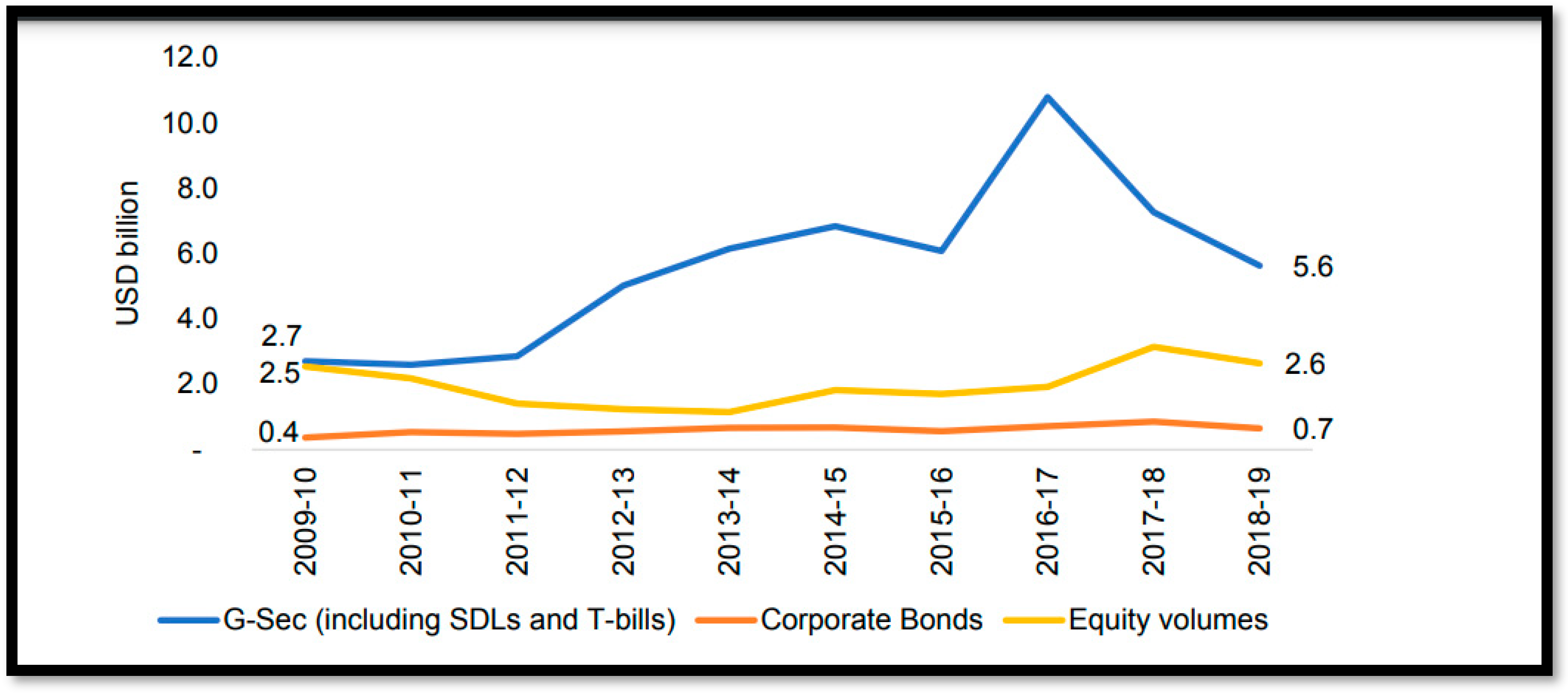

India’s corporate debt-to-GDP ratio was a meagre 17% in June 2017, compared to 123% in the United States and 19% in China. (

Reserve Bank of India Bulletin,2019)1.US corporate bonds have gone up by 44% from $5.42 trillion to $7.83 trillion from 2008-2014 (Goldstein et al., 2017) and U.S. Treasury market are the second largest sector of the bond market, after the mortgage market

.(Chakravarty & Sarkar, 2003). However, secondary bond market in India has not risen in consonance with the size of the market (RBI, 2022)2. The expansion of the corporate bond market has been a primary priority for policymakers in recent years. However, the average daily volume on the G-Sec and SDL markets has remained greater than the average daily volume on the corporate bond

(Acharya, 2020) so the prime concern is corporate bond market as shown if

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Source: (Acharya, 2020).

Figure 1.

Source: (Acharya, 2020).

Proxies of Liquidity

Research on the liquidity of corporate bonds has been done for a very long time due to its substantial practical value for issuers, investors, dealers, and the economy as a whole (Alexander et al., 2000) though it is substantially more difficult, because of the presence of credit risk and the smaller number of bonds per issuer (Houweling et al., 2005). Many researchers have identified the proxy to liquidity directly (Pan & Wang, 2010) or indirectly (Houweling et al., 2005) and factors affecting liquidity.

Friewald et al., 2010, employed bond characteristics and number of trades as liquidity proxy. Panel data using dummy variables have been used to find out the relationship between credit risk and liquidity. It has been found that lower liquidity for speculative grade bonds and the average trading cost increases for the investment grade bonds. Díaz & Escribano, 2022 found similar pattern with junk bonds having lower liquidity.

Saadaoui et al., 2022 used five different variables to measure liquidity which are credit rating, information asymmetry (bid-ask spread), volatility of price of bond, coupon of bond, age of the obligation, and interest rates. In this paper, panel data approach is used to analyse the result. Age found to be negatively related with liquidity whereas credit rating changes affects bond price, liquidity around the announcement date.

Chakravarty & Sarkar, 1999 in their paper found that liquidity is an important determinant of bid ask spread and the municipal bond spread ( the average buy price and the average sell price per bond per day) is higher than the government bond spread by about 9 cents per $100 par value, but the corporate bond spread is not. The government bond market is the most liquid market in US specially treasury market (Amihud & Mendelson, 1991; Fleming, 2002).Government bonds have the lowest age since issuance, and the highest trading volume of among corporate and municipal bond market. The bid-ask spread on corporate bonds grows with the bond’s age since issuance. Furthermore, the anticipated bid-ask gap for AAA and AA rated corporate bonds is around 21 cents lower than the spread for corporate junk bonds (bonds rated Ba or worse by Moody’s). Similar explanation given by (Dick-Nielsen et al., 2012) that the illiquidity of corporate bonds has been seen as a possible explanation for the ‘credit spread puzzle,’ means that yield spreads are higher on corporate bonds than other bonds. Similar explanation given by (Amihud & Mendelson, 1991),(Pan & Wang, 2010). The differences in liquidity are evidenced by the differences in the bid-ask spread, the brokerage fees, and the standard size of a transaction. (Amihud & Mendelson, 1991).

Hotchkiss & Jostova, 2017 in their paper found that compared to corporate with private equity, bonds issued by those with publicly listed stock are more likely to be traded. Additionally, publicly traded corporations with more active stocks also have more active bond markets. Finally, they demonstrated that, credit risk has a greater impact on the liquidity of high-yield bonds, interest-rate risk has a greater impact on the liquidity of investment-grade bonds.

According to Guo et al.,2017, uncertainty and liquidity are adversely associated. One of the fundamental elements contributing to the high level of illiquidity in the corporate bond market is uncertainty. Bonds with higher levels of uncertainty have lower trading volume, wider bid-ask spreads, and high price fluctuations.

Lee & Cho, 2016 in their paper investigated the issue size and age of bond are important determinants of bond liquidity. Liquidity of corporate bonds is influenced by changes in macroeconomic conditions. Most importantly, better corporate governance increases liquidity of corporate bonds.

Table 1.

Measurement of liquidity by researchers using various factors.

Table 1.

Measurement of liquidity by researchers using various factors.

| Factor |

Author |

Title |

Journal |

Contribution |

| Credit Rating Announcements |

Saadaoui et.al,2022 |

Credit rating announcement and bond liquidity: the case of emerging bond markets

|

Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science |

Credit rating announcement & Liquidity have direct relationship |

| Credit Risk |

Longstaff et al., 2005

|

Corporate yield spreads: Default risk or liquidity? New evidence from the credit default swap market |

The Journal of Finance |

Maturity, trade size, and credit ratings are key determinants of the bid-ask spread. |

| Corporate Governance, Issue Size and age of Bond |

Lee et.al, 2016 |

Corporate Governance and Corporate Bond Liquidity |

Global Economic Review |

Issue size, age and macro economic conditions are important determinants of bond liquidity |

| Size, Coupon, yield, age, Trading Volume |

(Eke et al., 2020),

(Alexander et al., 2000)

|

The Determinants of Trading Volume of High-Yield Corporate Bonds |

Journal of Financial Markets |

Yield and amount outstanding are key determinants of corporate bond liquidity |

| Breadth, depth, immediacy, resilience and tightness |

(Díaz & Escribano, 2022) |

Liquidity dimensions in the U.S. corporate bond market |

International Review of Economics and Finance |

Liquidity in bonds positively correlated with investment-grade and high-yield bonds |

III. Research Methodology

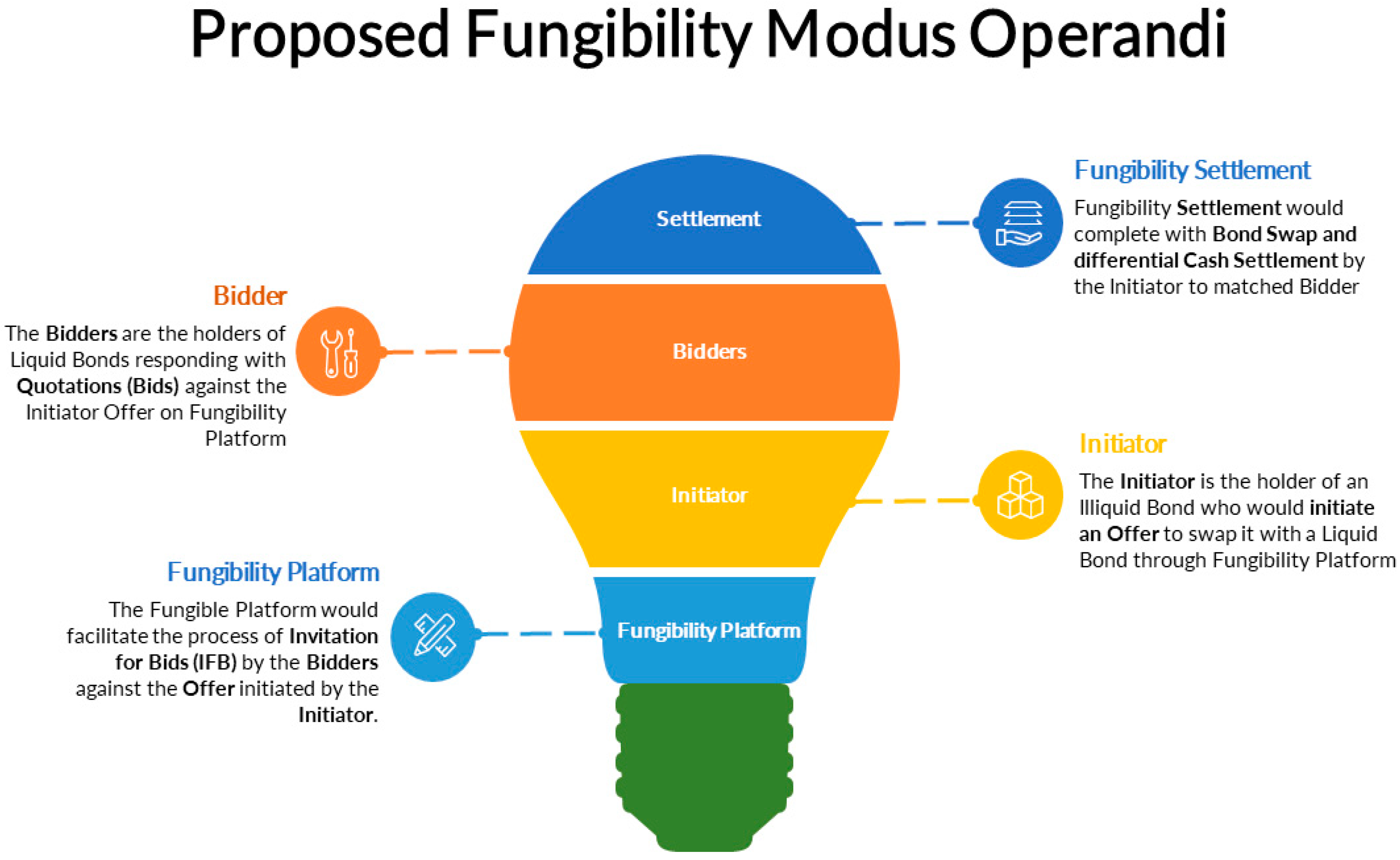

To develop a vibrant corporate debt market in any nation, it is essential to provide investors with a viable exit strategy. Traditionally, a financial instrument’s ’Liquidity’ is assumed to be reflected in an active secondary market. However, liquidity in secondary markets is based on a number of factors (Fleming, 2001) and the majority of secondary corporate debt markets around the world face issues in maintaining liquidity(Chakravarty & Sarkar, 1999). Current research investigates the viability of building an alternative to the ’Liquidity Route’ via the ’Fungibility Route’.

The fungibility path would allow for the swap of illiquid bonds for liquid bonds with differential cash settlement. To establish feasibility, it is essential to examine the following:

-

A.

Gravity of Illiquidity in corporate Bonds

-

B.

Liquidity in Government Bonds (G-Sec) and State Development Loans (SDL)

To validate the Illiquidity in Corporate Bonds a sample size of 2,34,772 trade data over 102 Days (with 72 Trading Days), covering 8 broad and 34 sub-categories of credit ratings

(Refer Table 7

) and 3,510 unique ISIN were sourced from Fixed Income Money Market and Derivatives Association of India (FIMMDA)

3.

To validate the Liquidity in Government Securities (G-Sec) and State Development Loans (SDL’s) a sample size of 2,00,607 trade data over 102 Days (with 72 Trading Days), covering 409 unique Government Securities (G-Sec) ISIN (International security identification number) and 1421 unique State Development Loans (SDL’s) ISIN were sourced from Clearing Corporation of India Ltd (CCIL)

4.

Table 2.

Credit Rating Categories.

Table 2.

Credit Rating Categories.

| |

Credit Rating Broad Categories |

| |

AAA |

AA |

A |

BBB |

BB |

B |

C |

D |

| Credit Rating Sub-Categories |

AAA+ |

AA+ |

A+ |

BBB+ |

BB+ |

B |

C |

D |

| AAA |

AA+(CE) |

A+(CE) |

BBB |

BB |

B- |

|

D- |

| AAA(CE) |

AA+(SO) |

A+(SO) |

BBB(SO) |

BB- |

|

|

|

| AAA(SO) |

AA |

A |

BBB- |

|

|

|

|

| |

AA(CE) |

A(SO) |

BBB-(SO) |

|

|

|

|

| |

AA(SO) |

A- |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

AA- |

A-(CE) |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

AA-(SO) |

A-(SO) |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

A3+ |

|

|

|

|

|

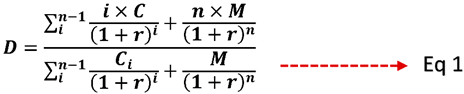

In order to calculate fungible value, we have adjusted risks of an illiquid bond.

-

a.

Interest rate risk or Interest rate sensitivity

Sensitivity Risk – Bonds differ in terms of Coupon, Frequency, Maturity and Yield. All these contribute to the sensitivity of a bond. Duration gauges the bond’s price sensitivity to changes in interest rates.(Ajlouni, 2012). Sensitivity can be measured more effectively with ‘Modified Duration (MD) of Bond. Modified Duration would be derived from the Duration (Macaulay) of the Bond.

Macaulay’s duration measures the weighted average time of all cash flows, including coupon payments, using the present values of the cash flows to determine the weighting.(Ajlouni, 2012) (Ingersoll et al., 1978), (Macaulay, 1999)

Macaulay’s duration measures the weighted average time of all cash flows, including coupon payments, using the present values of the cash flows to determine the weighting. (Ingersoll et al., 1978),(Macaulay, 1938).

Where,

D = Duration (Macaulay) of Bond

C = Coupon of Bond

M = Face or Par value

r = Effective periodic rate of interest

n = Number of periods to maturity

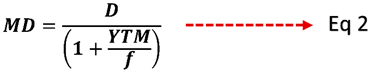

Where,

MD = Modified Duration of Bond

D = Duration (Macaulay) of Bond

YTM = Yield to Maturity

f = Frequency of Coupons

- b.

-

Credit risk-: Credit risk plays very important role in determining liquidity. High credit risk, lower would be liquidity. Credit Ratings indicates the credit and default risk associated with Bonds. We have used credit differential between two bonds having same maturity but different credit ratings.

Where,

CDF = Credit Differential Factor

= Latest Yield of Low Rated Bond

= Latest Yield of High Rated Bond

IV. Findings

- A.

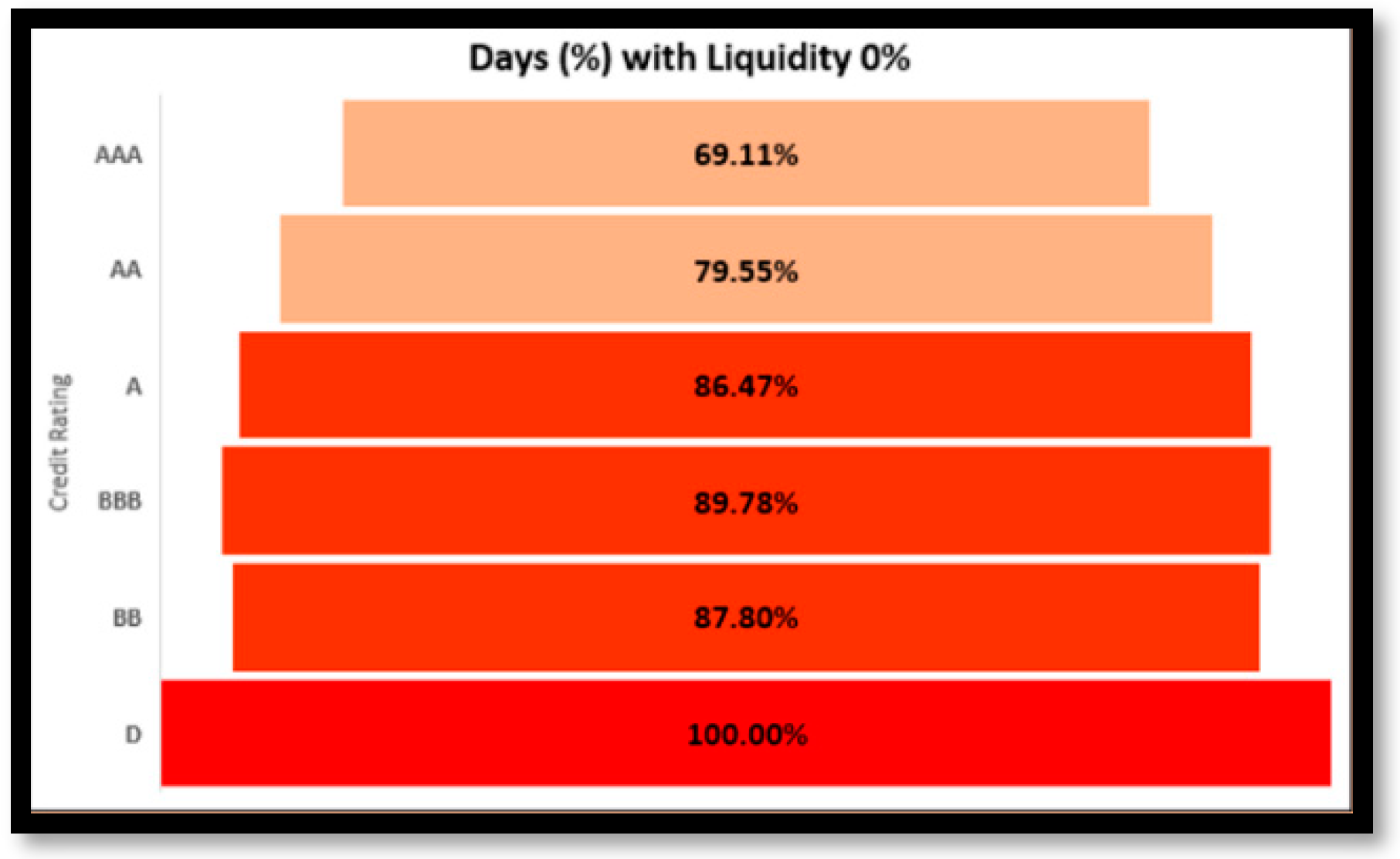

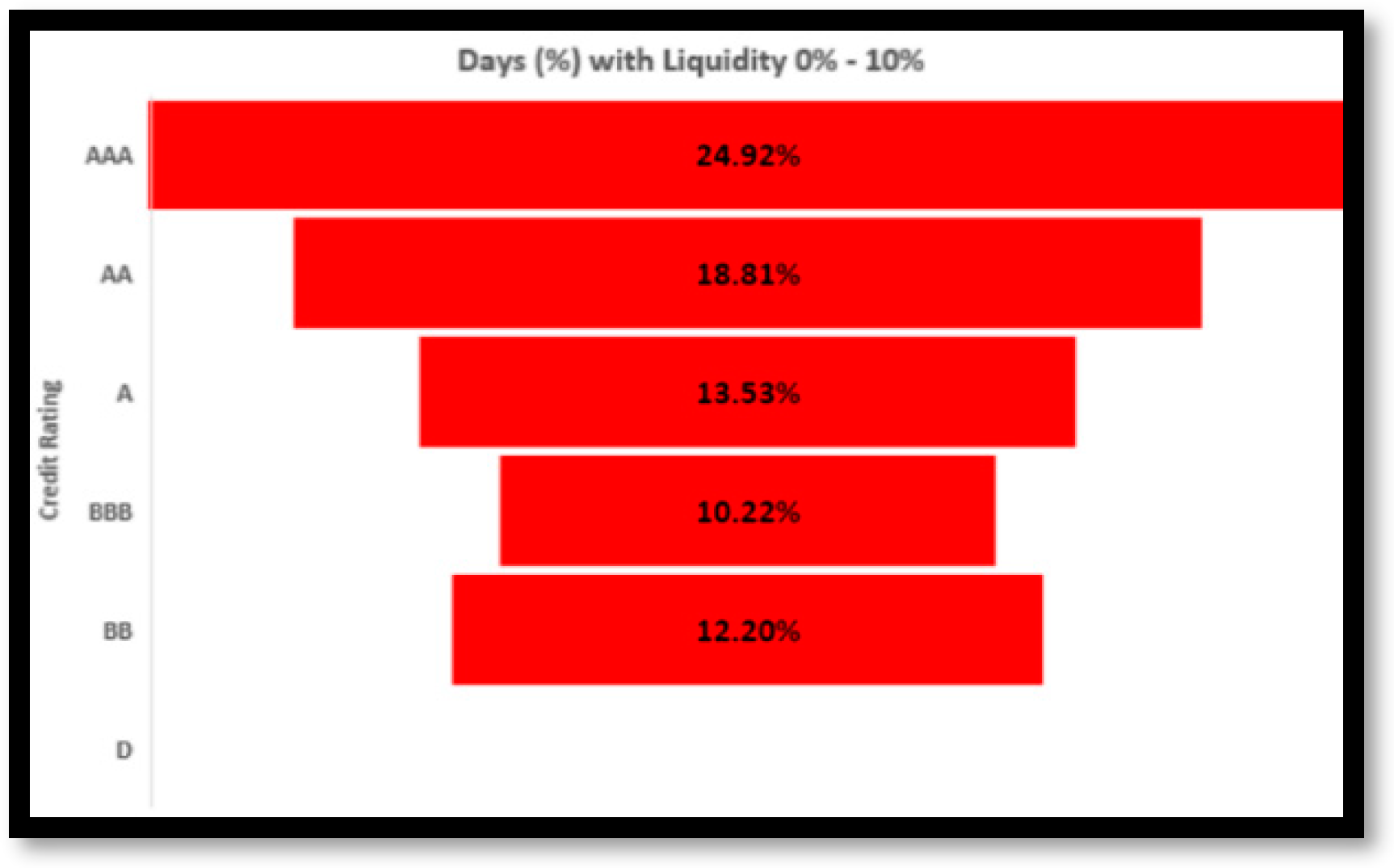

Gravity of Illiquidity in corporate Bonds The information was analyzed by grouping liquidity into eight broad credit ratings. It has been established that Liquidity has a direct correlation with Credit Rating

(Saadaoui et al., 2022). As the credit rating falls, liquidity also decreases. According to the Funnel Analysis tool (

Refer to Figure 2), the AAA Category of Bonds experienced 0% Liquidity on 69.11% of trading days, demonstrating the severity of illiquidity among the highest rated corporate bonds. As the rating goes to the lowest level, the frequency of liquidity lowers even further.

(Please refer to Figure 3)

Figure 2.

Gravity of Illiquidity in corporate Bonds.

Figure 2.

Gravity of Illiquidity in corporate Bonds.

Figure 3.

Liquidity decreases as credit rating decreases.

Figure 3.

Liquidity decreases as credit rating decreases.

Source: Author’s creation

Liquidity frequency as defined by the percentage of days traded between 0% and 10% also implies that Liquidity diminishes as Credit Ratings decrease (

Refer Table 3) It is safe to assume that the liquidity of corporate bonds is quite low, giving a vast opportunity for alternative Liquidity routes.

Table 3.

Percentage Days Liquidity Range across Credit Ratings.

Table 3.

Percentage Days Liquidity Range across Credit Ratings.

| |

Days % |

| Liquidity Range |

AAA |

AA |

A |

BBB |

BB |

D |

| 0% |

69.11% |

79.55% |

86.47% |

89.78% |

87.80% |

100.00% |

| 0% - 10% |

24.92% |

18.81% |

13.53% |

10.22% |

12.20% |

0.00% |

| 10% - 20% |

4.02% |

0.88% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| 20% - 30% |

0.89% |

0.51% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| 30% - 40% |

0.39% |

0.13% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| 40% - 50% |

0.39% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| 50% - 60% |

0.22% |

0.13% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| 60% - 70% |

0.06% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| 70% - 80% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| 80% - 90% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| 90% - 100% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

-

B.

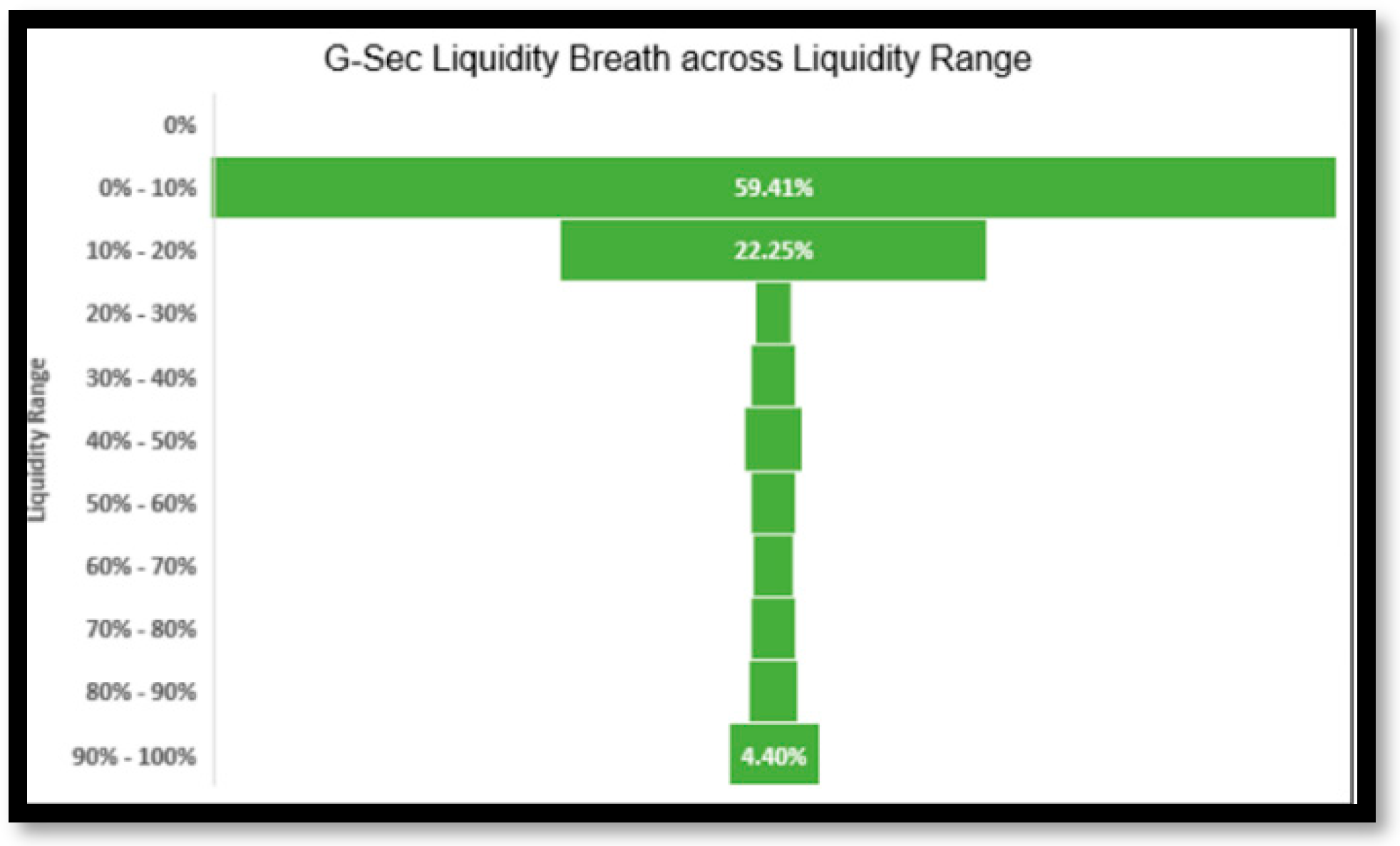

Liquidity in Government Bonds (G-Sec) and State Development Loans (SDL) - The data was analyzed by grouping the liquidity across Government Bonds (G-Sec) and State Development Loans (SDL). All ISINs in the G-Sec category are seen to be traded daily, showing a very high Liquidity Breath in the G-Sec category of Bonds. In addition, 81.66% of the bonds are traded between 0% and 20%.

(Refer Table 4 and Figure 4).

-

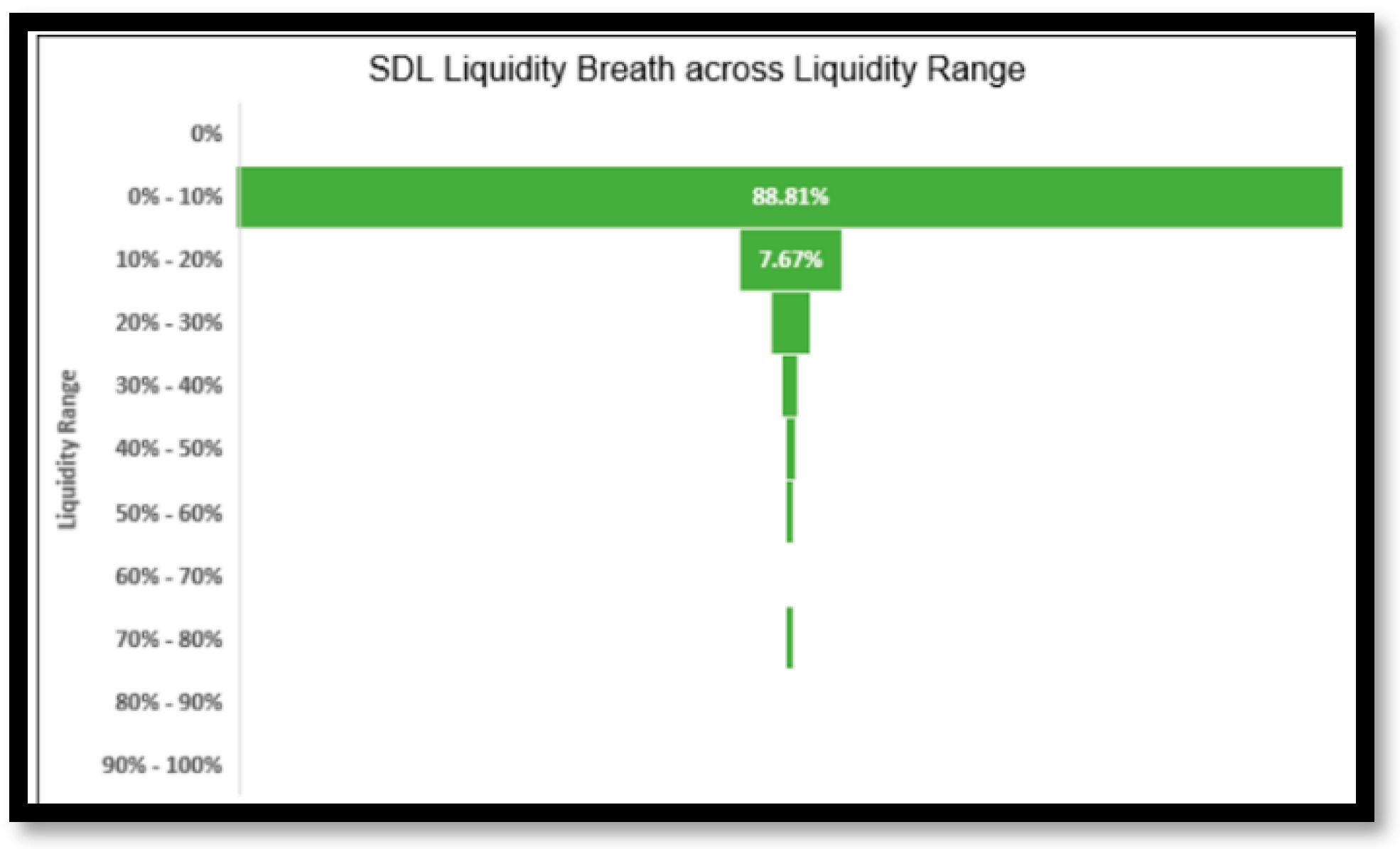

C.

All ISINs in the SDL category are seen to be traded daily, showing a very high Liquidity Breath in the SDL category of Bonds. In addition, 96.48% of the bonds are traded between 0% and 20%.

(Refer Table 5 and Figure 5).

Table 4.

Liquidity Breath in Government Bonds (G-Sec).

Table 4.

Liquidity Breath in Government Bonds (G-Sec).

| Liquidity Range |

ISIN Count |

ISIN Count (%) |

| 0% |

0 |

0.00% |

| 0% - 10% |

243 |

59.41% |

| 10% - 20% |

91 |

22.25% |

| 20% - 30% |

6 |

1.47% |

| 30% - 40% |

8 |

1.96% |

| 40% - 50% |

11 |

2.69% |

| 50% - 60% |

8 |

1.96% |

| 60% - 70% |

7 |

1.71% |

| 70% - 80% |

8 |

1.96% |

| 80% - 90% |

9 |

2.20% |

| 90% - 100% |

18 |

4.40% |

| Total |

409 |

100.00% |

Table 5.

Liquidity Breath in State Development Loans (SDL).

Table 5.

Liquidity Breath in State Development Loans (SDL).

| Liquidity Range |

ISIN Count |

ISIN Count (%) |

| 0% |

0 |

0.00% |

| 0% - 10% |

1262 |

88.81% |

| 10% - 20% |

109 |

7.67% |

| 20% - 30% |

36 |

2.53% |

| 30% - 40% |

10 |

0.70% |

| 40% - 50% |

2 |

0.14% |

| 50% - 60% |

1 |

0.07% |

| 60% - 70% |

0 |

0.00% |

| 70% - 80% |

1 |

0.07% |

| 80% - 90% |

0 |

0.00% |

| 90% - 100% |

0 |

0.00% |

| Total |

1421 |

100.00% |

Figure 4.

G-Sec Liquidity breath.

Figure 4.

G-Sec Liquidity breath.

Figure 5.

SDL Liquidity breath.

Figure 5.

SDL Liquidity breath.

Source: Author’s creation

V. Solution to the Problem

It should not be surprising, given the evidence, that the government debt market is one of the largest and most liquid. Still 59% of government bonds lie within the 0-10% liquidity band, whereas 88.8% of SDLs fall within the 0-10% liquidity range. It is evident, however, that the secondary corporate bond market is in serious distress, as 0% liquidity exists on 69% of trading days and 0%-10% liquidity exists on 25% of trading days for corporate bonds with the highest rating of ’AAA’. Despite the government’s efforts to promote liquidity through credit enhancement frameworks, dealer and issuer incentives, etc., there is a limited secondary market for bonds, particularly corporate bonds. Due to the secondary markets’ illiquidity, primary market participants are hesitant to subscribe, which ultimately results in illiquidity premiums. Corporates ask dealers for price quotes on bonds that aren’t being actively traded. When quoting an issue of an investment-grade bond, dealers can typically do so by comparing it to other bonds in the market (Schultz,1998). In light of the aforementioned challenges, we have proposed the "Fungibility Route" as a mechanism for bondholders to convert their illiquid corporate bond into a more liquid Central Government (G-Sec) or State Government (SDL) Bonds.

The biggest challenge in executing the fungibility deal is to arrive at the parity in value of two Bonds with different characteristics. Factors that differentiate bonds and the approach to bring parity with respect to differentiating factors are:

Credit Risks –Research on the corporate bond market shows that an increase in credit risk is associated with less liquidity (Chakravarty,2003; Longstaff et al., 2005). Credit Differential Factor (CDF) (Refer to Eq 1) between the Bonds under the Fungibility process would facilitate in restoring parity with respect to Credit Risks.

We have used below equation to calculate credit risk differential factor (Credit Differential Factor) between two bonds having different credit rating

Where,

CDF = Credit Differential Factor

= Latest Yield of Low Rated Bond

= Latest Yield of High Rated Bond

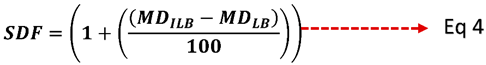

Sensitivity Risk –Sensitivity Differential Factor (SDF) (Refer to Eq 4) between the Bonds under the Fungibility process would facilitate in restoring parity with respect to Sensitivity Risks.

Where,

SDF = Sensitivity Differential Factor

= Modified Duration of the Illiquid Bond

= Modified Duration of the Liquid Bond

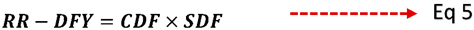

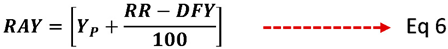

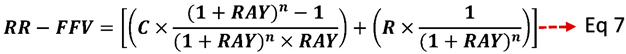

Credit Risk Differential and Sensitivity Differential would largely restore parity when consolidated as RR-Differential Factor Yield (Refer to Eq 5). This would further be used to arrive at the Risk Adjusted Yield (Discounting Factor) (Refer to Eq 6) to arrive at the RR-Fungible Fair Value (RR-FFV) (Refer to Eq 7) of the illiquid bond.

Where,

RR-DFY = RR – Differential Factor Yield

CDF = Credit Differential Factor

SDF = Sensitivity Differential Factor

Where,

RAY = Risk Adjusted Yield

RR-DFY = RR – Differential Factor Yield

= Yield at Par

Where,

RR-FFV = RR – Fungible Fair Value

C = Coupon

R = Redemption Value

n = Maturity

RAY = Risk Adjusted Yield

The above RR-Fungible Fair Value (RR-FFV) does not adjust for the Liquidity Risk as the Bond is not traded in the market. Hence, the Bidders would collectively derive the most appropriate liquidity risk premium through Bidding.

The above estimations are depicted below in Table with hypothetical values to derive at the RR-Fungible Fair Value (RR-FFV).

Fungibility would be a boon to the development of the Global Corporate Debt Market.(Miller & Puthenpurackal, 2005) The Fungibility route would serve as an alternative to the liquidity route in order to facilitate the selling of less liquid, yet secure, corporate bonds. This would not only enable the fair pricing of debt papers and funds, but it would also increase investor confidence in the debt market.

The proposed fungibility route can be visualized as an additional segment on existing exchanges that facilitates Trading, Clearing, and Settlement in the Debt Segment. The platform should be designed to facilitate the ‘Invitation for Bids (IFB)’ process.

The parties in the Fungibility process to execute the Invitation for Bids (IFB) would be:

Fungibility Platform – Exchange or other dedicated electronic platform

Initiator – The holder of an illiquid bond who initiates an Offer to Swap the illiquid bond with the Government Bonds (G-Sec) and State Development Loans (SDL)

Bidders – The Bidders are willing to swap their liquid Government Bonds (G-Sec) or State Development Loans (SDL) with a high rated safe illiquid corporate bond available at a favourable price to enhance their portfolio yield.

Figure 6.

Proposed Fungibility Modus Operandi.

Figure 6.

Proposed Fungibility Modus Operandi.

Conclusion

It is safe to conclude that the liquidity of Government Bonds (G-Sec) and State Development Loans (SDL) is high and that they can serve as an effective instrument for the fungible route to produce liquidity in less liquid high-rated corporate bonds. Fair Value must be estimated prior to initiating any transaction using the Fungible Route. The estimated fair value (RR-FFV) would serve as a starting point for bidders, with this price acting as an implied upper limit. Bidders would naturally offer a lower price to compensate for the "Illiquidity Risk" inherent in the corporate bond. However, the highest bid would be accepted by the initiator, allowing the market forces to determine the optimal price.

In order to get the RR-Fungible Fair Value (RR-FFV), the preceding illustration exhibits an illiquid corporate bond (X) with a credit rating of ’AA’ and a liquid government bond (GS) in order to calculate the RR-FFV (Y). Coupons and Maturity are also distinct between the two bonds. Consequently, reflecting the disparities in bond credibility (ratings) and sensitivity (maturity, coupon, frequency, etc.). Credit risk is higher in illquid bond (Chakravarty,2003; Longstaff et al., 2005) and hence more compensation is required to exchange the bond with high liquidity.

Credit Differential Factor (CDF) is calculated as the most recent credit spread between the respective ratings in order to reinstate the disparity in the underlying credit and default risk associated with Bonds ’X’ and ’Y’. In this instance, it is 1.167 percent (

Refer to Table 6). More illiquid bond has higher yield spread.

(Schultz, 1998, Chen.etal, 2007)

Table 6.

RR-Fungible Fair Value.

Table 6.

RR-Fungible Fair Value.

| Fungible Fair Value Model |

| |

|

|

| Parameters |

Illiquid Bond (X) |

Liquid Bond (Y) |

| Rating |

AA |

GS |

| Settlement Date |

27-Nov-14 |

5-Oct-16 |

| Maturity Date |

27-Nov-25 |

5-Oct-25 |

| Par |

100 |

100 |

| Coupon |

8.00% |

6.00% |

| Frequency |

1 |

1 |

| Maturity |

11.00 |

9.00 |

| Redemption |

100 |

100 |

| Yield |

8.00% |

6.00% |

| Duration |

7.71 |

7.21 |

| Modified Duration |

7.14 |

6.80 |

| Theoretical Value |

100.00 |

100.00 |

| |

|

|

| Analytical Parameters |

Values |

|

| Credit Differential Factor (CDF) |

1.1678 |

|

| Sensitivity Differential Factor (SDF) |

1.0034 |

| RR-Differential Factor Yield (RR-DFY) |

1.1717 |

| Risk Adjusted Yield (RAY) |

9.1717% |

| RR-Fungible Fair Value (RR-FFV) |

92.0904 |

To rectify the gap in the underlying sensitivity caused by the difference between Coupons and Maturity, the Sensitivity Differential Factor (SDF) must be determined. Bond theorems have already demonstrated the sensitivity relationships for bonds (Refer to Table 7).

Table 7.

Sensitivity Bond Theorems.

Table 7.

Sensitivity Bond Theorems.

| Bond Parameters |

Sensitivity Relationship |

Interpretation |

| Coupon |

Inverse |

Higher the Coupon, Lower the Sensitivity of the Bond |

| Frequency of Coupons |

Inverse |

Higher the Frequency of Coupons, Lower the Sensitivity of the Bond |

| Maturity |

Direct |

Higher the Maturity, Higher the Sensitivity of the Bond |

Table 7.

Ratings and Spreads

5.

Table 7.

Ratings and Spreads

5.

| |

Rating-wise Yield (%) |

Credit Spreads (%) |

| Date |

GS-5Y |

SDL-5Y |

AAA-5Y |

AA-5Y |

A-5Y |

GS-SDL |

GS-AAA |

GS-AA |

GS-A |

SDL-AAA |

SDL-AA |

SDL-A |

| 01-12-22 |

7.0680 |

7.4000 |

7.5278 |

8.2403 |

10.0471 |

0.3320 |

0.4598 |

1.1723 |

2.9791 |

0.1278 |

0.8403 |

2.6471 |

| 02-12-22 |

7.0720 |

7.3500 |

7.5313 |

8.2438 |

10.0506 |

0.2780 |

0.4593 |

1.1718 |

2.9786 |

0.1813 |

0.8938 |

2.7006 |

| 05-12-22 |

7.0850 |

7.3700 |

7.5416 |

8.2541 |

10.0609 |

0.2850 |

0.4566 |

1.1691 |

2.9759 |

0.1716 |

0.8841 |

2.6909 |

| 06-12-22 |

7.1070 |

7.4400 |

7.5581 |

8.2706 |

10.0773 |

0.3330 |

0.4511 |

1.1636 |

2.9703 |

0.1181 |

0.8306 |

2.6373 |

| 07-12-22 |

7.1390 |

7.3700 |

7.5871 |

8.2996 |

10.1063 |

0.2310 |

0.4481 |

1.1606 |

2.9673 |

0.2171 |

0.9296 |

2.7363 |

| 09-12-22 |

7.1800 |

7.4200 |

7.6320 |

8.3445 |

10.1513 |

0.2400 |

0.4520 |

1.1645 |

2.9713 |

0.2120 |

0.9245 |

2.7313 |

| 12-12-22 |

7.1660 |

7.3600 |

7.6240 |

8.3365 |

10.1433 |

0.1940 |

0.4580 |

1.1705 |

2.9773 |

0.2640 |

0.9765 |

2.7833 |

| 13-12-22 |

7.1330 |

7.3600 |

7.5827 |

8.2952 |

10.1020 |

0.2270 |

0.4497 |

1.1622 |

2.9690 |

0.2227 |

0.9352 |

2.7420 |

| 14-12-22 |

7.1050 |

7.5600 |

7.5536 |

8.2661 |

10.0729 |

0.4550 |

0.4486 |

1.1611 |

2.9679 |

-0.0064 |

0.7061 |

2.5129 |

| 15-12-22 |

7.1240 |

7.4800 |

7.5793 |

8.2918 |

10.0986 |

0.3560 |

0.4553 |

1.1678 |

2.9746 |

0.0993 |

0.8118 |

2.6186 |

The bond’s sensitivity can be represented by its ’Duration’ (refer to Eq. 2), and more effectively by its ’Modified Duration’ (Refer to Eq 3). The Corporate Bond (X) in the preceding illustration has a Modified Duration of 7.14, indicating that if the Yield changes by 1%, the Bond Price will change by 7.14%, whereas the Government Bond (Y) has a Modified Duration of 6.80, indicating that if the Yield changes by 1%, the Bond Price will change by 6.80%.

A Sensitivity Differential Factor (SDF) is calculated by relative difference of the respective modified durations of Bonds ’X’ and ’Y’ with a value of 1.0034 in order to restore the discrepancy in risks deriving from the bonds’ varied sensitivities (Refer to Eq 4). The value of SDF 1.0034 indicates that the Corporate Bond (X) is 1.0034 times more sensitive than the Government Bond (Y).

To reinstate the entire disparity (credit and sensitivity) impact on Yield, the RR-Differential Factor Yield (RR-DFY) (Refer to Equation 5) is calculated by multiplying the Credit Differential Factor (CDF) and Sensitivity Differential Factor (SDF) (SDF). The RR-DFY value of 1.1717 indicates that a premium of 1.1717 percent must be added to the par yield to determine the final Risk Adjusted Yield (RAY) (Refer to Eq 6).

The Risk Adjusted Yield (RAY) of 9.1717% (8.0000% + 1.1717%) represents the final discounting rate used to determine the RR-Fungible Fair Value (RR-FFV) of the bond (refer to Eq. 7). The RR-FFV of 92.0904 reflects the fair value that bidders should quote on the higher side. The value does not include the premium for liquidity risk that is anticipated to be determined by the collective bidding procedure among all eligible bidders. Therefore, this value should ideally serve as a ceiling for all bidders, who should begin bidding below the predicted RR-FFV.

VI. Limitations and way forward

In this paper, we have proposed an exit strategy to the bondholders using fungibility route. The suggested Fungible Model’s limitations overlook the differential risks coming from embedded options and other hybrid characteristics tied to the Bond. In this scenario, the market would collectively determine the premium through Bidding.

Getting data at all times is the most difficult challenge in case of measuring bond’s liquidity. The bid-ask spread is the most demonstrable metric, although it is not always available for all bonds or for all time periods; particularly true for thinly traded bonds. (Chen et.al, 2007). Our research corroborates with other researchers in terms of establishing relationship between yield spread and liquidity. Yield spread is higher in case of illiquid bonds (Favero, 2010; Chen.et.al, 2007). Feasibility study of fungibility in other markets of the world can be studied to make it widely accepted.

References

- Ajlouni, Mohd. (2012). Properties and limitations of duration as a measure of time structure of bond and interest rate risk. International Journal of Economic Perspectives. 6. 46-56.

- Alexander Eisl, Christian Ochs, Jonas Staghøj, Marti G. Subrahmanyam, Sovereign issuers, incentives and liquidity: The case of the Danish sovereign bond market, Journal of Banking & Finance, Volume 140, 2022, 106485.

- Alexander, Gordon & Edwards, Amy & Ferri, Michael. (2000). The Determinants of Trading Volume of High-Yield Corporate Bonds. Journal of Financial Markets. 3. 177-204. 10.1016/S1386-4181(00)00005-7. [CrossRef]

- Amihud, Y., & Mendelson, H. (1991). Liquidity, Maturity, and the Yields on U.S. Treasury Securities. The Journal of Finance, 46(4), 1411–1425. https://doi.org/10.2307/2328864. [CrossRef]

- Aramonte, S., & Avalos, F. (2020). The recent distress in corporate bond markets: Cues from ETFs.

- Antonio Díaz, Ana Escribano, Liquidity dimensions in the U.S. corporate bond market, International Review of Economics & Finance, Volume 80, 2022, Pages 1163-1179, ISSN 1059-0560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2022.04.008. [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty.S.,Sarkar.A.(2003). Trading Costs in Three U.S. Bond Markets.The Journal of Fixed Income. https://doi.org/10.3905/jfi.2003.319345. [CrossRef]

- Christopher, R., Kim, S.J. and Wu, E. (2012), “Do sovereign credit ratings influence regional stock and bond market interdependencies in emerging countries?”, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, Vol. 22 No. 4, pp. 1070-1089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2012.01.003. [CrossRef]

- Dick-Nielsen, J., Feldhütter, P., & Lando, D. (2009). Corporate Bond Liquidity Before and after the Onset of the Subprime Crisis. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1339910. [CrossRef]

- Eke, Patrick & Adetiloye, Kehinde & Adegbite, Esther. (2020). An Analysis of Bond Market Liquidity and Real Sector Output in Selected African Economies. E+M Ekonomie a Management. 23. 166-181. . [CrossRef]

- Fleming, M.J. (2003), “Measuring treasury market liquidity”, Economic Policy Review, Vol. 9 No. 3, p. 57.

- Fleming, M. J. (2002). Are Larger Treasury Issues More Liquid? Evidence from Bill. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 34(3b), 707–735. https://doi.org/10.1353/mcb.2002.0013. [CrossRef]

- Friewald, N., Jankowitsch, R., & Subrahmanyam, M. G. (2010). Illiquidity or Credit Deterioration: A Study of Liquidity in the US Corporate Bond Market during Financial Crises. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1420294. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L., Lien, D., Hao, M., & Zhang, H. (2017). Uncertainty and liquidity in corporate bond market.Applied Economics,1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2017.1293792, 10.1080/00036846.2017.1293792. [CrossRef]

- Hotchkiss, E., & Jostova, G. (2017). Determinants of Corporate Bond Trading: A Comprehensive Analysis. Quarterly Journal of Finance, 07(02), 1750003. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2010139217500033. [CrossRef]

- Houweling, P., Mentink, A., & Vorst, T. (2005). Comparing possible proxies of corporate bond liquidity. Journal of Banking & Finance, 29(6), 1331–1358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004.04.007. [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, J., Skelton, J. and Weil, R. (1978), Duration Forty Years Later, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, Vol. 13, Nov., pp. 627-650.

- Itay Goldstein, Hao Jiang, David T. Ng, Investor flows and fragility in corporate bond funds, Journal of Financial Economics, Volume 126, Issue 3, 2017, Pages 592-613, ISSN 0304-405X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2016.11.007. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. J., & Cho, I. (2016). Corporate Governance and Corporate Bond Liquidity. Global Economic Review, 45(2), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/1226508x.2015.1137483, 10.1080/1226508x.2015.1137483. [CrossRef]

- Longstaff, F. A., Mithal, S., & Neis, E. (2005). Corporate yield spreads: Default risk or liquidity? New evidence from the credit default swap market. The Journal of Finance, 60(5), 2213–2253.

- Lesmond, D. A., Chen, L., & Wei, J. Z. (2005). Corporate Yield Spreads and Bond Liquidity. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.495422. [CrossRef]

- Macauley, F. (1938), Some Theoretical Problems Suggested by the Movement of Interest Rates, Bond Yields, and Stock Prices in the US Since 1856, New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Patrick Houweling, Albert Mentink, Ton Vorst, Comparing possible proxies of corporate bond liquidity, Journal of Banking & Finance, Volume 29, Issue 6, 2005, Pages 1331-1358, ISSN 0378-4266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004.04.007. [CrossRef]

- Patrick Houweling, Albert Mentink, Ton Vorst, Comparing possible proxies of corporate bond liquidity, Journal of Banking & Finance, Volume 29, Issue 6, 2005, Pages 1331-1358, ISSN 0378-4266, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004.04.007. [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. P., & Puthenpurackal, J. J. (2005). Security Fungibility and the Cost of Capital: Evidence from Global Bonds, The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis , Dec., 2005, Vol. 40, No. 4 (Dec., 2005), pp. 849-872.

- Saadaoui, A., Elammari, A. and Kriaa, M. (2022), "Credit rating announcement and bond liquidity: the case of emerging bond markets", Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, Vol. 27 No. 53, pp. 86-104.

- Schou-Zibell, L., & Wells, S. (2008). India’s Bond Market—Developments and Challenges Ahead. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1328192. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P., 1998, Corporate bond trading costs and practices: A peek behind the curtain, working paper, University of Notre Dame.

- Simon Gilchrist, Vladimir Yankov, Egon Zakrajšek, Credit market shocks and economic fluctuations: Evidence from corporate bond and stock markets, Journal of Monetary Economics, Volume 56, Issue 4,2009, Pages 471-493, ISSN 0304-3932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2009.03.017. [CrossRef]

- Zoran Ivanovski, Toni Draganov Stojanovskib & Nadica Ivanovska (2013). Interest Rate Risk of Bond Prices on Macedonian Stock Exchange - Empirical Test of the Duration, Modified Duration and Convexity and Bonds Valuation, Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 26:3, 47-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2013.11517621. [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I., Cater, T., 2015. Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organ. Res. Methods 18 (3), 429e472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114562629. [CrossRef]

- Wells, Stephen; Schou-Zibell, Lotte. 2008. India’s Bond Market— Developments and Challenges Ahead. © Asian Development Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/11540/1971. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Where,

Where,