Submitted:

14 July 2023

Posted:

17 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Nutritional Value

2. Perception of Food with Insect Additives

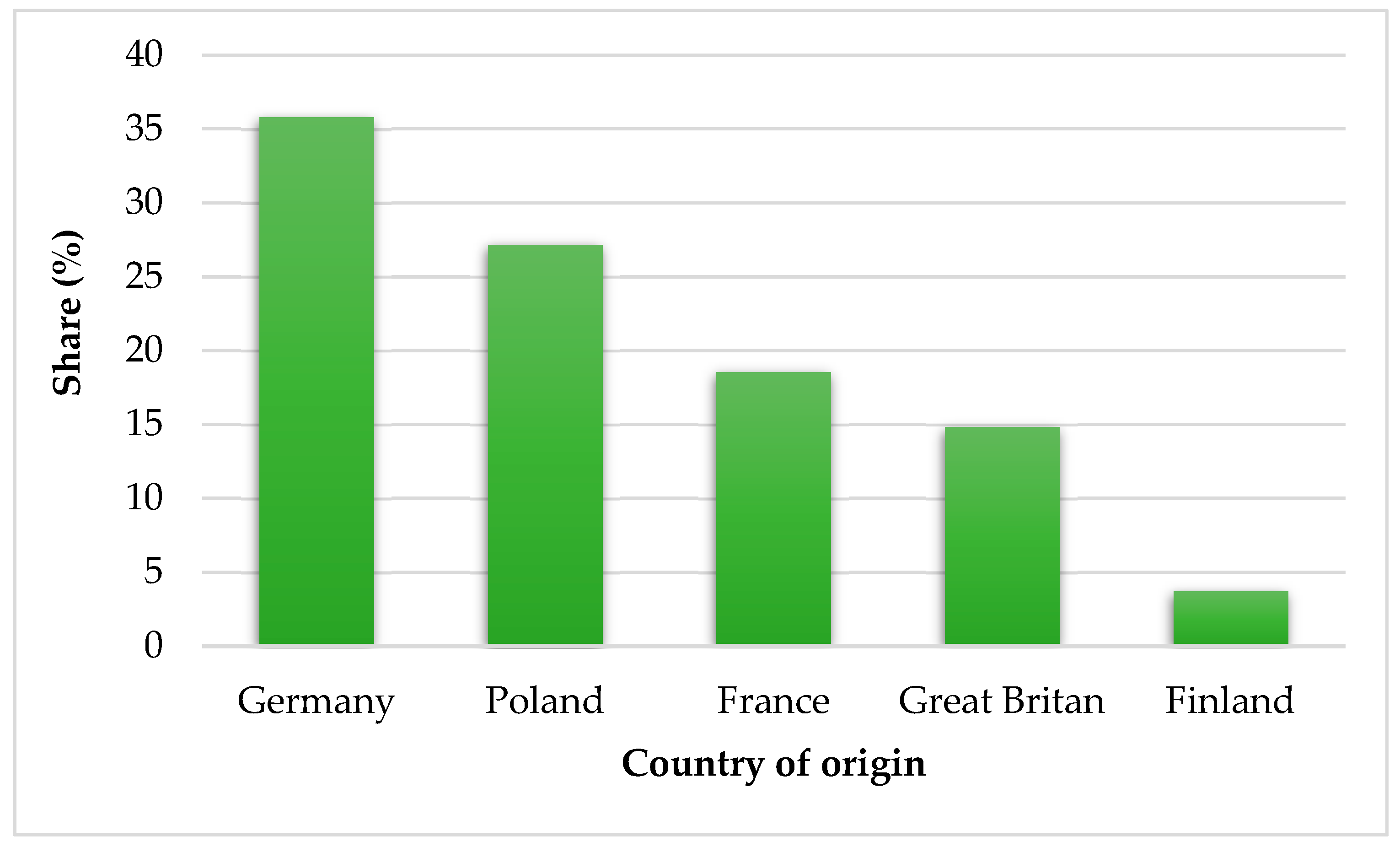

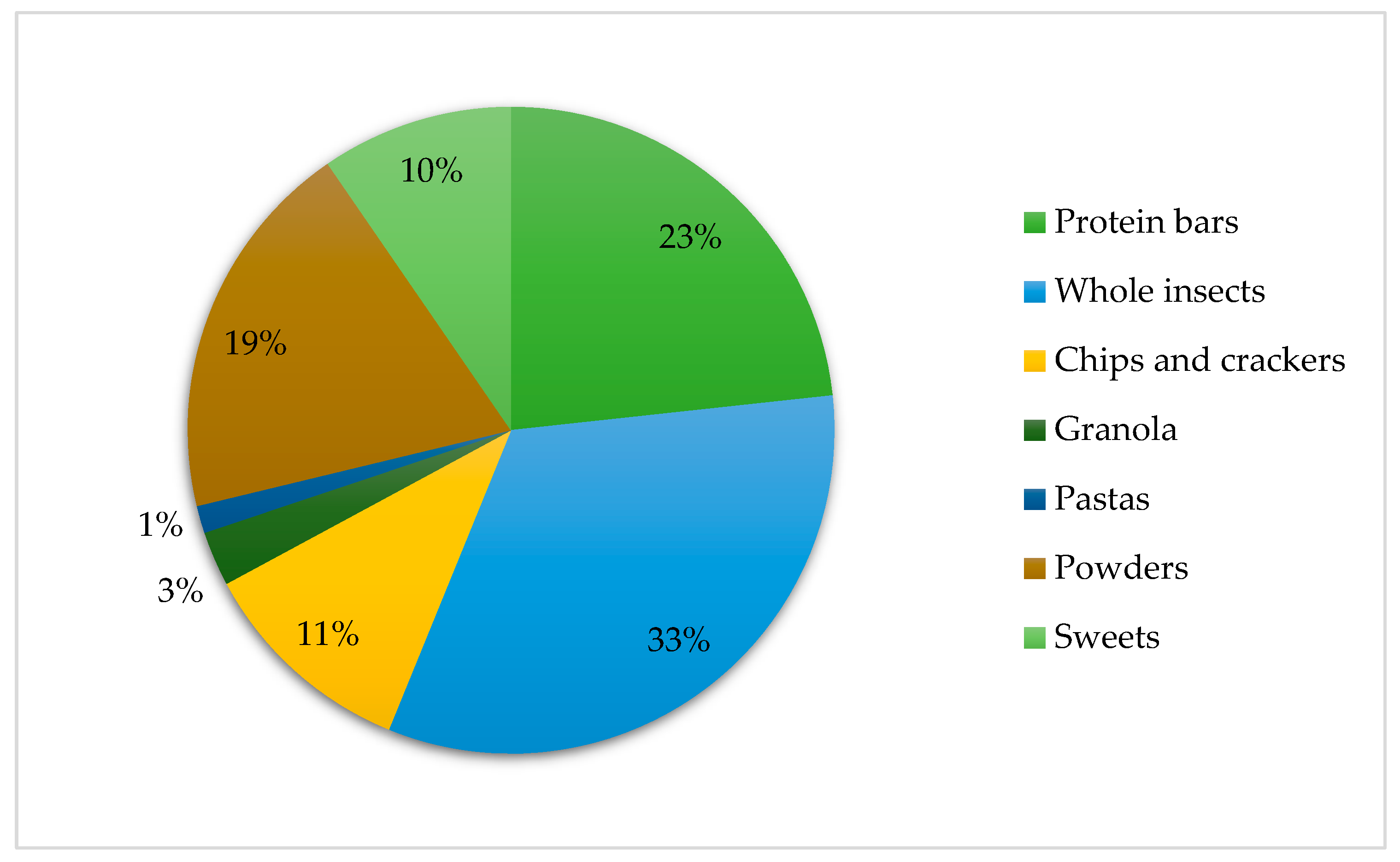

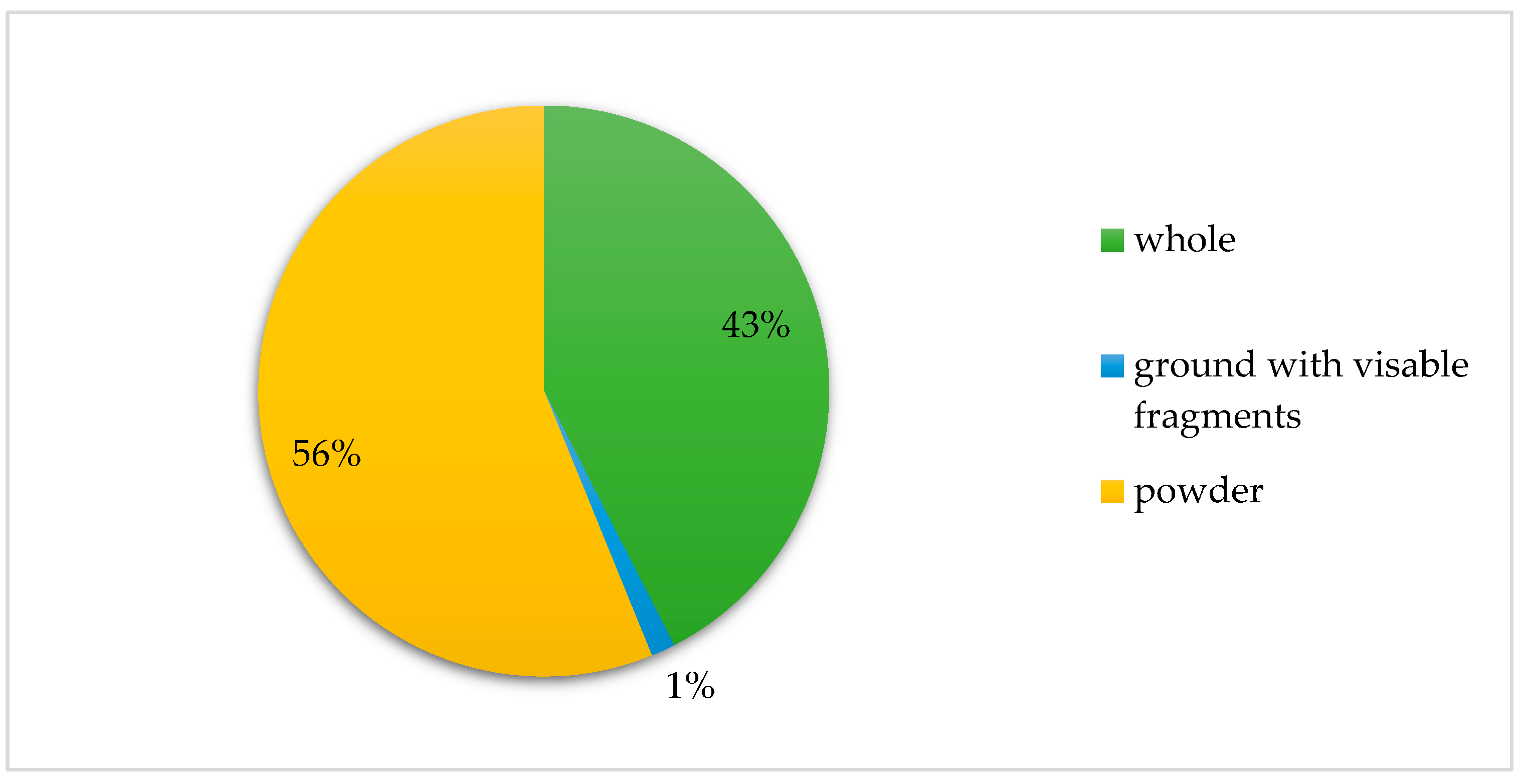

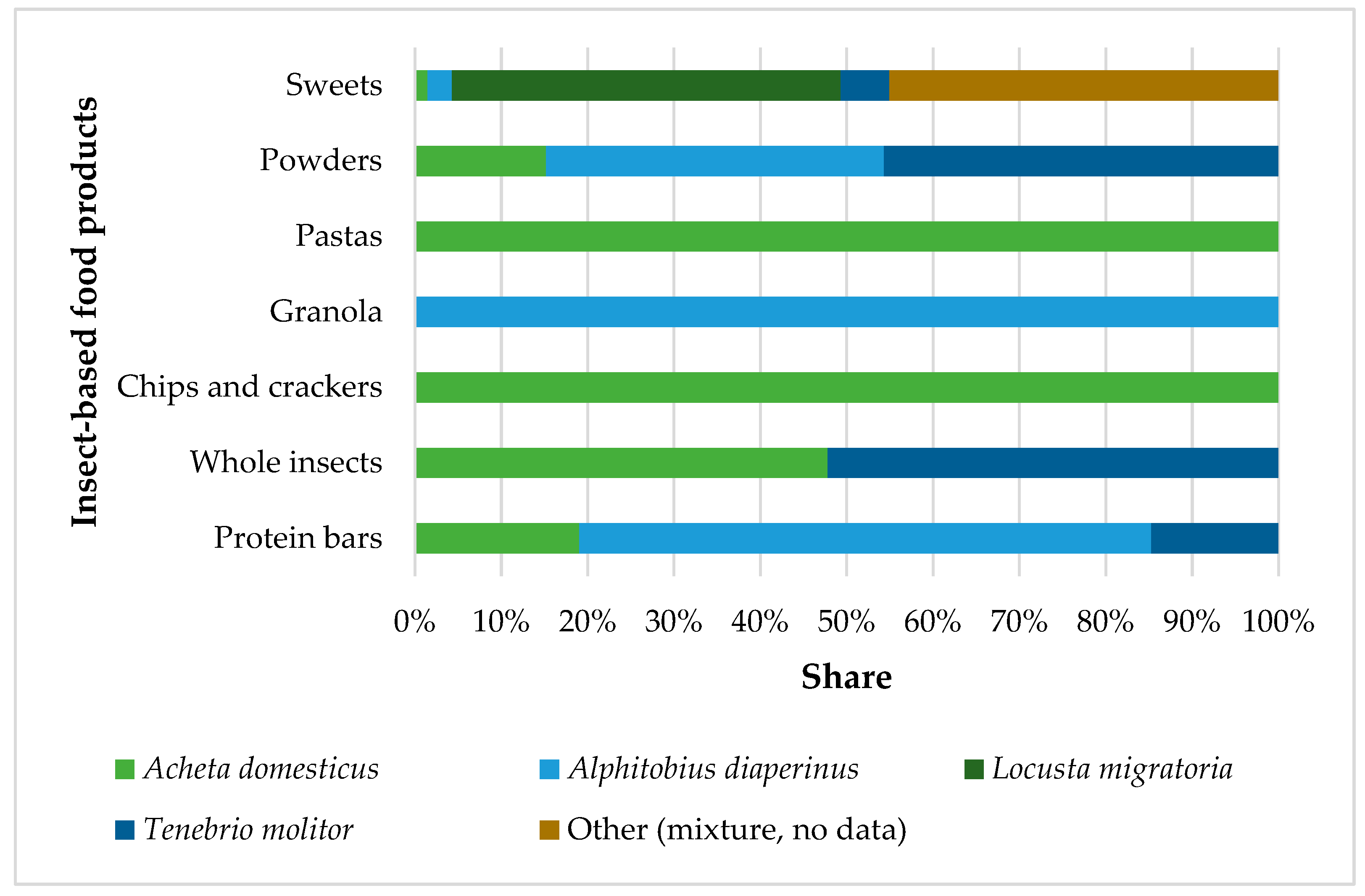

3. Market Availability

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Verneau, F.; La Barbera, F.; Kolle, S.; Amato, M.; Del Giudice, T.; Grunert, K. The effect of communication and implicit associations on consuming insects: An experiment in Denmark and Italy. Appetite 2016, 106, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vauterin, A.; Steiner, B.; Sillman, J.; Kahiluoto, H. The potential of insect protein to reduce food-based carbon footprints in Europe: The case of broiler meat production. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez-Araque, R.; Egas-Montenegro, E. Edible insects: A food alternative for the sustainable development of the planet. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueschke, M.; Gramza-Michałowska, A.; Kubiak, T.; Kulczyński, B. Alternatywne źródła białka w żywieniu człowieka. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW w Warszawie - Probl. Rol. Światowego 2017, 17, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, S.; Bekhit, A.E.D.; Grune, T.; Schlüter, O.K. Bioavailability of nutrients from edible insects. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 41, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, E.; Zieliński, D.; Jakubczyk, A.; Karaś, M.; Pankiewicz, U.; Flasz, B.; Dziewięcka, M.; Lewicki, S. The impact of polystyrene consumption by edible insects Tenebrio molitor and Zophobas morio on their nutritional value, cytotoxicity, and oxidative stress parameters. Food Chem. 2021, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas-Levi, A.; Martinez, J.J.I. The high level of protein content reported in insects for food and feed is overestimated. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2017, 62, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, E.; Karaś, M.; Baraniak, B. Comparison of functional properties of edible insects and protein preparations thereof. Lwt 2018, 91, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, C.; Xia, X. free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID- Advances in mRNA vaccines. 2020, 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kouřimská, L.; Adámková, A. Nutritional and sensory quality of edible insects. NFS J. 2016, 4, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowicz, J. Owady jadalne w aspekcie żywieniowym, ekonomicznym i środowiskowym. Handel Wewnętrzny 2018, 2, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wiza, P.L. Charakterystyka owadów jadalnych jako alternatywnego źródła białka w ujęciu żywieniowym, środowiskowym oraz gospodarczym. Postępy Tech. przetwórsta spożywczego 2019, 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek, K. Alternatywne i egzotyczne źródła białka zwierzęcego w żywieniu człowieka w kontekście racjonalnego wykorzystania zasobów środowiska. Polish J. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 24, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, M.; Dossey, A.T. Insects for Human Consumption; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; ISBN 9780123914538. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann, K.K.; Merz, M.; Appel, D.; De Araujo, M.M.; Fischer, L. New insights into the flavoring potential of cricket (Acheta domesticus) and mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) protein hydrolysates and their Maillard products. Food Chem. 2021, 364, 130336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeja, N. Entomofagia – Aspekty Żywieniowe I Psychologiczne. Kosmos 2019, 68, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumpold, B.A.; Schlüter, O.K. Nutritional composition and safety aspects of edible insects. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 802–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Bueno, R.P.; González-Fernández, M.J.; Sánchez-Muros-Lozano, M.J.; García-Barroso, F.; Guil-Guerrero, J.L. Fatty acid profiles and cholesterol content of seven insect species assessed by several extraction systems. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2016, 242, 1471–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossey, A.T.; Tatum, J.T.; McGill, W.L. Modern Insect-Based Food Industry: Current Status, Insect Processing Technology, and Recommendations Moving Forward; Elsevier Inc., 2016; ISBN 9780128028568. [Google Scholar]

- Zielińska, E.; Baraniak, B.; Karaś, M.; Rybczyńska, K.; Jakubczyk, A. Selected species of edible insects as a source of nutrient composition. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, M.; Olsson, V.; Wendin, K. Reasons for eating insects? Responses and reflections among Swedish consumers. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 22, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, H.; FitzGibbon, L.; Millan, E.; Murayama, K. Curious to eat insects? Curiosity as a Key Predictor of Willingness to try novel food. Appetite 2022, 168, 105790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishyna, M.; Chen, J.; Benjamin, O. Sensory attributes of edible insects and insect-based foods – Future outlooks for enhancing consumer appeal. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 95, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendin, K.M.; Nyberg, M.E. Factors influencing consumer perception and acceptability of insect-based foods. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 40, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niva, M.; Vainio, A. Towards more environmentally sustainable diets? Changes in the consumption of beef and plant- and insect-based protein products in consumer groups in Finland. Meat Sci. 2021, 182, 108635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumussoy, M.; Macmillan, C.; Bryant, S.; Hunt, D.F.; Rogers, P.J. Desire to eat and intake of ‘insect’ containing food is increased by a written passage: The potential role of familiarity in the amelioration of novel food disgust. Appetite 2021, 161, 105088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion-Poulin, A.; Turcotte, M.; Lee-Blouin, S.; Perreault, V.; Provencher, V.; Doyen, A.; Turgeon, S.L. Acceptability of insect ingredients by innovative student chefs: An exploratory study. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.; Choi, J. Consumer acceptance of edible insect foods: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2021, 15, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.P.; Ma, C.C.; Chen, H.S. Climate change and consumer’s attitude toward insect food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, S.; Moruzzo, R.; Riccioli, F.; Paci, G. European consumers’ readiness to adopt insects as food. A review. Food Res. Int. 2019, 122, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, A.C.; Hung, Y.; Olthof, M.R.; Verbeke, W.; Brouwer, I.A. Older consumers’ readiness to accept alternative, more sustainable protein sources in the European Union. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, P.; Ullmann, L.M.; Fiebelkorn, F. Acceptance of insects as food in Germany: Is it about sensation seeking, sustainability consciousness, or food disgust? Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 77, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, L.; Voege, L.L.; Stranieri, S. Eating edible insects as sustainable food? Exploring the determinants of consumer acceptance in Germany. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125, 108573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Videbæk, P.N.; Grunert, K.G. Disgusting or delicious? Examining attitudinal ambivalence towards entomophagy among Danish consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 83, 103913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparros Megido, R.; Sablon, L.; Geuens, M.; Brostaux, Y.; Alabi, T.; Blecker, C.; Drugmand, D.; Haubruge, É.; Francis, F. Edible insects acceptance by belgian consumers: Promising attitude for entomophagy development. J. Sens. Stud. 2014, 29, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Profiling consumers who are ready to adopt insects as a meat substitute in a Western society. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Bogueva, D.; Marinova, D. Australian consumers’ response to insects as food. Agric. 2019, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, J.; Fiebelkorn, F. Attitudes and acceptance of young people toward the consumption of insects and cultured meat in Germany. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 85, 103983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, M.B.; Rozin, P.; Chan, C. Determinants of willingness to eat insects in the USA and India. J. Insects as Food Feed 2015, 1, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya, C.; Sterling, K.; Rukov, J.L.; Roos, N. Perception of edible insects and insect-based foods among children in Denmark: educational and tasting interventions in online and in-person classrooms. J. Insects as Food Feed 2023, 9, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, K.W.; Nakamura, Y. Edible insects as future food: chances and challenges. J. Futur. Foods 2021, 1, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros-Baró, M.; Sánchez-Socarrás, V.; Santos-Pagès, M.; Bach-Faig, A.; Aguilar-Martínez, A. Consumers’ Acceptability and Perception of Edible Insects as an Emerging Protein Source. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, D.; Carrascosa, C.; Oluwole, O.B.; Nieuwland, M.; Saraiva, A.; Millán, R.; Raposo, A. Traditional consumption of and rearing edible insects in Africa, Asia and Europe. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2169–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skotnicka, M.; Karwowska, K.; Kłobukowski, F.; Borkowska, A.; Pieszko, M. Possibilities of the development of edible insect-based foods in europe. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartkowicz, J.; Babicz-Zielińska, E. Acceptance of bars with edible insects by a selected group of students from Tri-City, Poland. Czech J. Food Sci. 2020, 38, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florença, S.G.; Correia, P.M.R.; Costa, C.A.; Guiné, R.P.F. Edible insects: Preliminary study about perceptions, attitudes, and knowledge on a sample of portuguese citizens. Foods 2021, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrastardottir, R.; Olafsdottir, H.T.; Thorarinsdottir, R.I. Yellow mealworm and black soldier fly larvae for feed and food production in europe, with emphasis on iceland. Foods 2021, 10, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, S.; Sogari, G.; Diaz, S.E.; Menozzi, D.; Paci, G.; Moruzzo, R. Exploring the Future of Edible Insects in Europe. Foods 2022, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma, R.; Palmisano, G.O.; De Boni, A. Insects as novel food: A consumer attitude analysis through the dominance-based rough set approach. Foods 2020, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).