Submitted:

14 July 2023

Posted:

17 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

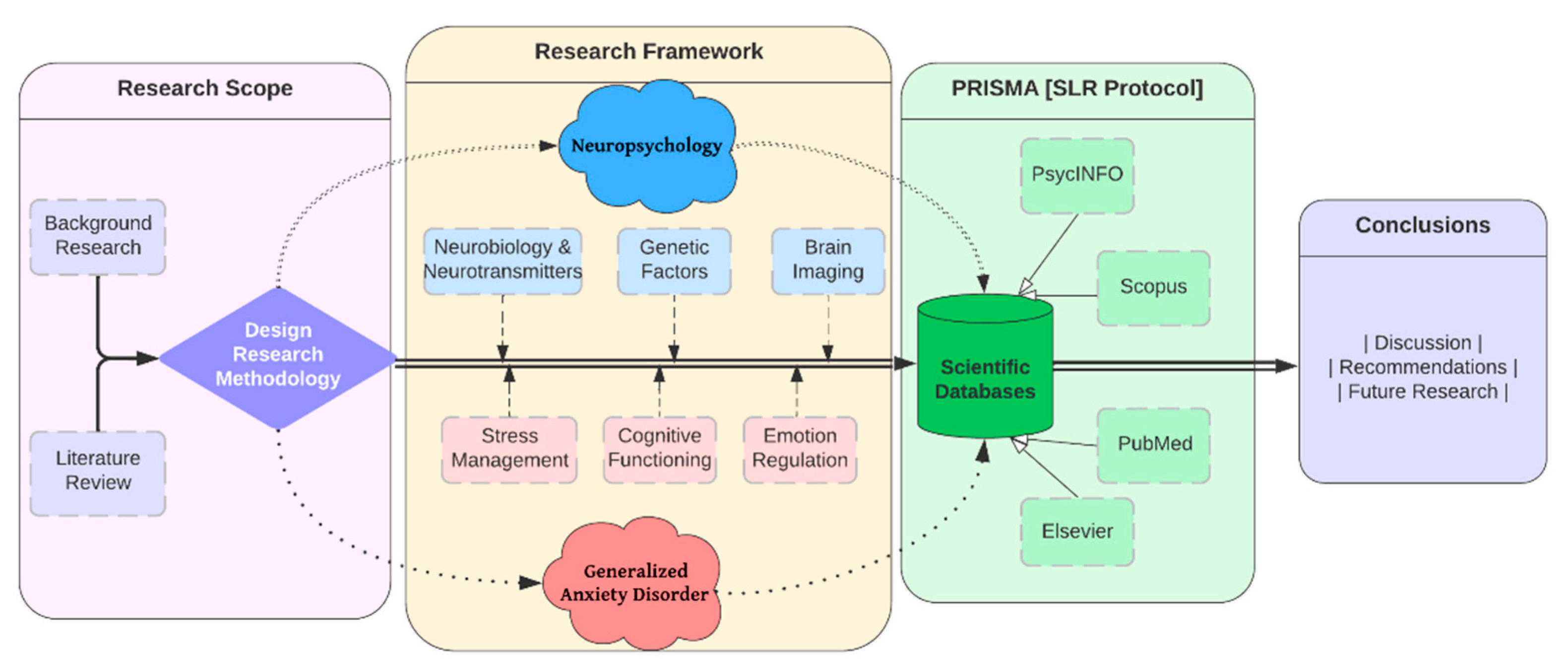

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

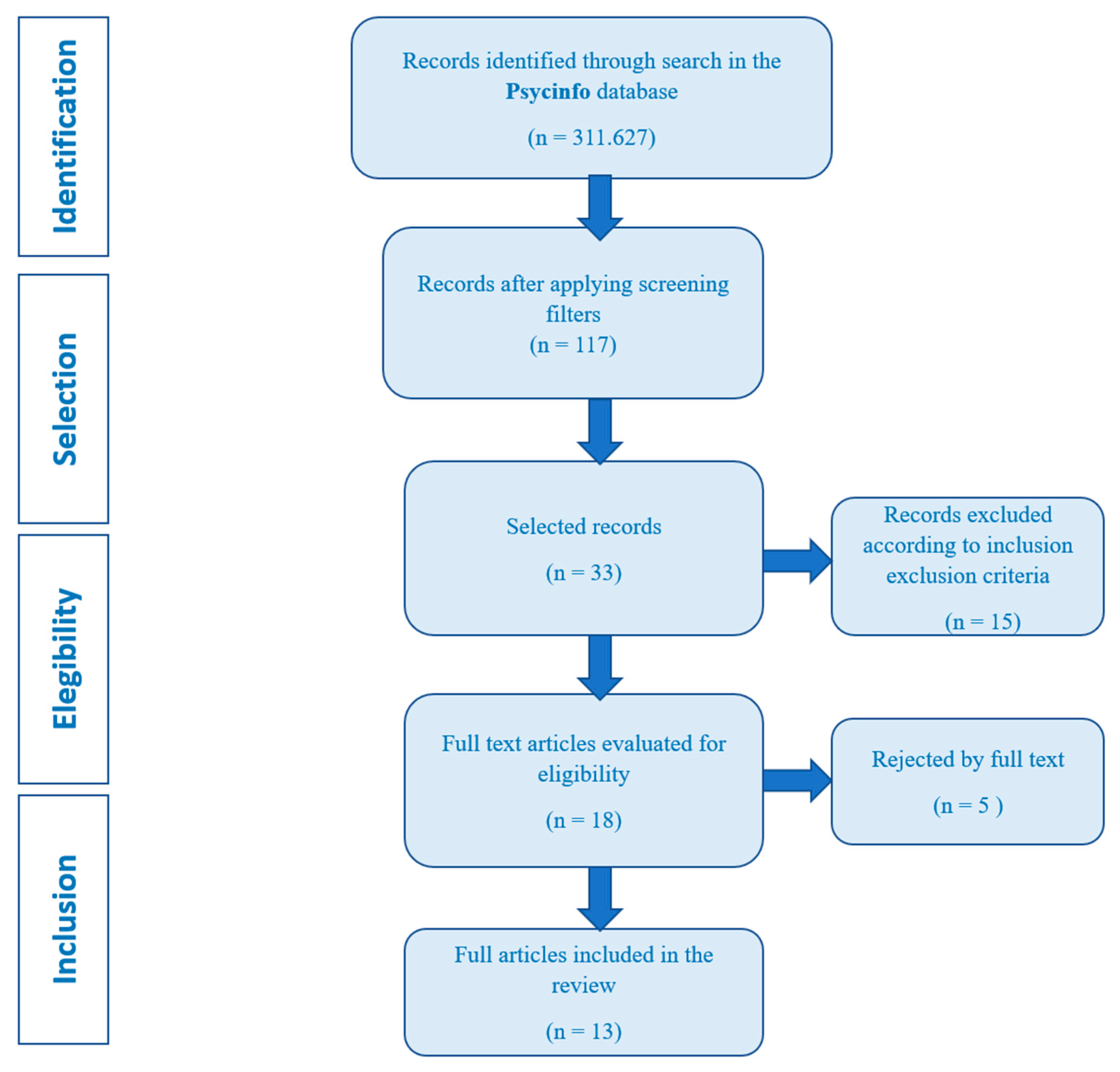

4.1. Information sources and search strategies

4.2. Empirical studies

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aasvik, J. K., Woodhouse, A., Jacobsen, H. B., Borchgrevink, P. C., Stiles, T. C., & Landrø, N. I. (2015). Subjective memory complaints among patients on sick leave are associated with symptoms of fatigue and anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Pallis, E., Bitsios, P., Giakoumaki, S. (2017). “Neurocognitive performance, psychopathology and social functioning in individuals at high-genetic risk for schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder”. International Journal of Affective Disorders 208, 512-520. [CrossRef]

- Timulak, L. (2017). Generalized anxiety disorder. Transforming Generalized Anxiety, 8–28. [CrossRef]

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder. (2022). Child and Adolescent Psychopathology for School Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, M. (2018). Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Evolutionary Psychopathology, 319–322. [CrossRef]

- De la Peña-Arteaga, V., Fernández-Rodríguez, M., Silva Moreira, P., Abreu, T., Portugal-Nunes, C., Soriano-Mas, C., Picó-Pérez, M., Sousa, N., Ferreira, S., & Morgado, P. (2022). An fMRI study of cognitive regulation of reward processing in generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 324, 111493. [CrossRef]

- Newman, M. G., Zainal, N. H., & Hoyer, J. (2020). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Worrying, 203–230. Portico. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Thiel, L., & Graff, N. de. (2022). Mindfulness and Relaxation Techniques for Stroke Survivors with Aphasia: A Feasibility and Acceptability Study. Healthcare, 10(8), 1409. [CrossRef]

- Rippe, J. M. (2020). Promoting Regular Physical Activity. Increasing Physical Activity, 173–188. [CrossRef]

- Substance/Medication-Induced Anxiety Disorder. (2017). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Abnormal and Clinical Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Halkiopoulos, C., Antonopoulou, H. (2022). Neuroleadership an Asset in Educational Settings: An Overview. Emerging Science Journal. Emerging Science Journal, 6(4), 893–904. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A. L., & Owens, L. (2020). Mechanisms of change in dialectical behavior therapy. The Handbook of Dialectical Behavior Therapy, 51–69. [CrossRef]

- Whittingham, K., & Coyne, L. W. (2019). Integrating Acceptance and Commitment Therapy with other interventions. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, 377–402. [CrossRef]

- Portman, M. E. (2009). Pharmacotherapy for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Generalized Anxiety Disorder Across the Lifespan, 65–84. [CrossRef]

- Balderston, N. L., Vytal, K. E., O’Connell, K., Torrisi, S., Letkiewicz, A., Ernst, M., & Grillon, C. (2016). Anxiety Patients Show Reduced Working Memory Related dlPFC Activation During Safety and Threat. Depression and Anxiety, 34(1), 25–36. Portico. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J. M., Phan, K. L., Kennedy, A. E., Shankman, S. A., Langenecker, S. A., & Klumpp, H. (2017). Prefrontal and amygdala engagement during emotional reactivity and regulation in generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 218, 398–406. [CrossRef]

- Fonzo, G. A., Ramsawh, H. J., Flagan, T. M., Sullivan, S. G., Simmons, A. N., Paulus, M. P., & Stein, M. B. (2014). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder is associated with attenuation of limbic activation to threat-related facial emotions. Journal of Affective Disorders, 169, 76–85. [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, S. A., Posokhov, S. I., Kovrov, G. V., & Katenko, S. V. (2013). Psychophysiological characteristics of panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Zhurnal nevrologii i psikhiatrii imeni SS Korsakova, 113(5), 11-14.

- Hallion, L. S., Tolin, D. F., Assaf, M., Goethe, J., & Diefenbach, G. J. (2017). Cognitive Control in Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Relation of Inhibition Impairments to Worry and Anxiety Severity. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41(4), 610–618. [CrossRef]

- Khdour, H. Y., Abushalbaq, O. M., Mughrabi, I. T., Imam, A. F., Gluck, M. A., Herzallah, M. M., & Moustafa, A. A. (2016). Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Social Anxiety Disorder, but Not Panic Anxiety Disorder, Are Associated with Higher Sensitivity to Learning from Negative Feedback: Behavioral and Computational Investigation. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 10. [CrossRef]

- Plana, I., Lavoie, M.-A., Battaglia, M., & Achim, A. M. (2014). A meta-analysis and scoping review of social cognition performance in social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder and other anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(2), 169–177. [CrossRef]

- Moon, C.-M., & Jeong, G.-W. (2015). Functional neuroanatomy on the working memory under emotional distraction in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 69(10), 609–619. Portico. [CrossRef]

- Renna, M. E., Seeley, S. H., Heimberg, R. G., Etkin, A., Fresco, D. M., & Mennin, D. S. (2017). Increased Attention Regulation from Emotion Regulation Therapy for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42(2), 121–134. [CrossRef]

- Stefanopoulou, E., Hirsch, C. R., Hayes, S., Adlam, A., & Coker, S. (2014). Are attentional control resources reduced by worry in generalized anxiety disorder? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(2), 330–335. [CrossRef]

- Tempesta, D., Mazza, M., Serroni, N., Moschetta, F. S., Di Giannantonio, M., Ferrara, M., & De Berardis, D. (2013). Neuropsychological functioning in young subjects with generalized anxiety disorder with and without pharmacotherapy. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 45, 236–241. [CrossRef]

- White, S. F., Geraci, M., Lewis, E., Leshin, J., Teng, C., Averbeck, B., Meffert, H., Ernst, M., Blair, J. R., Grillon, C., & Blair, K. S. (2017). Prediction Error Representation in Individuals With Generalized Anxiety Disorder During Passive Avoidance. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(2), 110–117. S. (. [CrossRef]

- Patel, N., Stoodley, C., Pine, D. S., Grillon, C., & Ernst, M. (2017). Interaction of induced anxiety and verbal working memory: influence of trait anxiety. Learning & Memory, 24(9), 407–413. [CrossRef]

- Gorka, S. M., Lieberman, L., Shankman, S. A., & Phan, K. L. (2017). Association between neural reactivity and startle reactivity to uncertain threat in two independent samples. Psychophysiology, 54(5), 652–662. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, W. A., & Kirkland, T. (2013). The joyful, yet balanced, amygdala: moderated responses to positive but not negative stimuli in trait happiness. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(6), 760–766. [CrossRef]

- Ward, T., Delrue, N., & Plagnol, A. (2017). Neuropsychotherapy as an integrative framework in counselling psychology:The example of trauma. Counselling Psychology Review, 32(4), 18–28. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Boutsinas, B., Kourkoutas, E. (2022). Developmental Trauma and Neurocognition in Young Adults. 14th Annual International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, 4th – 6th July, Mallorca, Spain. [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, S., Gurvich, C., Sumner, P., Tan, E., Thomas, E., & Rossell, S. (2018). T75. GENERAL AND EXECUTIVE COGNITIVE PROFILES: GENERAL COGNITIONS INFLUENCE ON WCST PERFORMANCE. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(suppl_1), S143–S143. [CrossRef]

- Wells, A. (n.d.). The Metacognitive Model of Worry and Generalised Anxiety Disorder. Worry and Its Psychological Disorders, 177–199. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, I. M., & Palm, M. E. (n.d.). Pharmacological Treatments for Worry: Focus on Generalised Anxiety Disorder. Worry and Its Psychological Disorders, 305–334. [CrossRef]

- Berg, C. (2021). The Fundamental Nature of Anxiety. Fear, Punishment Anxiety and the Wolfenden Report, 83–100. [CrossRef]

- Bashford-Largo, J., Aloi, J., Zhang, R., Bajaj, S., Carollo, E., Elowsky, J., Schwartz, A., Dobbertin, M., Blair, R. J. R., & Blair, K. S. (2021). Reduced neural differentiation of rewards and punishment during passive avoidance learning in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 38(8), 794–803. Portico. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. (2019). Treating anxiety sensitivity in adults with anxiety and related disorders. The Clinician’s Guide to Anxiety Sensitivity Treatment and Assessment, 55–75. [CrossRef]

- McHugh, R. K. (2019). Assessing anxiety sensitivity. The Clinician’s Guide to Anxiety Sensitivity Treatment and Assessment, 9–29. [CrossRef]

- Halkiopoulos, C., Antonopoulou, H., Gkintoni, E., & Aroutzidis, A. (2022). Neuromarketing as an Indicator of Cognitive Consumer Behavior in Decision-Making Process of Tourism destination—An Overview. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics, 679–697. [CrossRef]

- Fung, K., Alden, L. E., & Sernasie, C. (2021). Social anxiety and the acquisition of anxiety towards self-attributes. Cognition and Emotion, 35(4), 680–689. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Gkintoni, E., Katsibelis, A. (2022). Application of Gamification Tools for Identification of Neurocognitive and Social Function in Distance Learning Education. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 21(5), 367–400. [CrossRef]

- Nakamae, T. (2017). Neuromodulation for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Anxiety Disorder Research, 9(1), 50–56. [CrossRef]

- WANG, G.-X., & LI, L. (2013). Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy of Anxiety Disorders. Advances in Psychological Science, 20(8), 1277–1286. [CrossRef]

| Author (year) | Type of study | Sample | Instrument | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aasvik et al. (2015) [1] | Quantitative | 167 patients | Clinical assessment: clinical questionnaires to measure memory complaints (EMQ-R), chronic pain (SF-8), depression and anxiety (HADS), fatigue (CFQ) and insomnia (ISI) | Significant levels of fatigue and anxiety while those of depression, insomnia and intensity of pain are not. Subjective memory complaints may reflect concerns about one's own memory performance, so it is an expression of anxiety, becoming anxious when asked to remember something. Anxiety consumes attention. |

| Balderston et al. (2017) [15] | Quantitative | 69 participants from the Washington DC metropolitan area |

Participants completed measures of anxiety: Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), State/Trait Anxiety Scale, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) |

There is a deterioration in performance in patients with anxiety, slower reaction time, difficulty recruiting some regions in cognitive tasks, there are intrusive thoughts and low control over them, low regulation of emotions, they have to make efforts to face fearful stimuli, continuous thoughts related to threats during tasks. |

| Fitzgerald et al. (2017) [16] |

Qualitative | 69 individuals |

A block-design Emotion Regulation Task (ERT) |

Individuals with trait anxiety exhibit deficits in cognitive control mediated by the dIPFC; in this study, they experimentally manipulate threat, and it is found that patients with anxiety demonstrated performance deficits. These results suggest that poor cognitive control is a stable trait in patients with anxiety. Furthermore, these results generate a testable hypothesis that WM deficits may predict the future severity of symptoms or the outcome of treatment. |

| Fonzo et al. (2014) [17] | Quantitative | 32 individuals (21 adults with a principal diagnosis of a generalized anxiety disorder and 11 non-anxious healthy controls) | PSWQ, 10 sessions of weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy, the Emotion Face Assessment Task | It provides evidence for a dual-process psychotherapeutic model of changes in neural systems in generalized anxiety disorder in which cingulo-amygdala reactivity to threat signals is attenuated while insular responses to positive facial emotions are potentiated. |

| Gordeev et al. (2013) [18] | Quantitative | 95 patients (34 patients with panic disorder, 32 patients with generalized anxiety disorder and 29 healthy) | Clinical-neurological, psychometric, neuropsychological, and neurophysiological methods | Patients with generalized anxiety disorder differed from patients with panic disorder by a higher level of anxiety, a greater degree of depression, and more reported disorders of short-term memory and directed attention. They also had lower P300 amplitudes but in panic patients they were higher. |

| Hallion et al. (2017) [19] | Quantitative | 56 participants (35 of them had generalized anxiety disorder, the other 21 had no history of mental health, treatment, or mental disorders) | Has been used: MINI, CSR, CGI, SIGH-A, PSWQ, SIGH-D | Generalized anxiety states predicted impaired 'cool' inhibition and impaired cognitive inhibition, although not for the worry trait. Anxiety affects cognitive efficiency by requiring more effort (reflected in part by slower response times) to maintain adequate overall performance (reflected in task accuracy), and that this increased effort is partly attributable to the presence of worry, which competes for attentional resources. |

| Khdour et al. (2016) [20] | Quantitative | 73 participants from clinics associated with the universities of Cairo and Ain Shams. | The North American Adult Reading Test (NAART), the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R), Digit Span test and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A). | Patients with generalized anxiety learned better from negative feedback. There is a cognitive dissociation between the subtypes of anxiety spectrum disorders, which could underlie a difference in the neural circuitry involved in these disorders. Enhanced learning from negative feedback in people with generalized anxiety is not attributed to group differences in speed of learning or the ability to explore available outcomes. |

| Plana et al. (2014) [21] | Quantitative | 1417 anxious patients and 1321 non-clinical controls. | 40 studies evaluating mentalization, emotion recognition, social perception/knowledge, or attributional style in anxiety disorders | The results indicate different patterns of deterioration of social cognition: people with post-traumatic stress disorder show deficits in mentalization and emotion recognition while other anxiety disorders showed attributional biases. |

| Moon et al. (2015) [22] | Quantitative | 36 right-hand subjects (18 patients with generalized anxiety disorder and 18 healthy controls) | The subjects underwent structured clinical interviews for DSM-IV diagnosis 18 and various psychiatric rating scale: HAMD 17, GAD-7, STAI-I, STAIII, ASI-R | Patients with generalized anxiety disorder showed significant differences on all questionnaires compared to healthy controls.Therefore, this finding suggests that patients with generalized anxiety tend to respond to anxiety-related situations with fear, lower accuracy, and a combination of cognitive deficits. with low attention. |

| Renna et al. (2018) [23] | Qualitative | 17 participants from two different clinics in the northeastern of United States | Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV and the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV | Patients with generalized anxiety disorder present a deficit in attention regulation. They found that a greater ability to sustain attention may be an indicator of clinical improvement. Worry is the hallmark of generalized anxiety, and it inhibits the ability to divert attention because of this, they pay more attention to the threat. There is a decrease in social skills (due to lack of maintenance of attention). |

| Stefanopoulou et al. (2014) [24] | Quantitative | 17 participants after their first session of cognitive-behavioral treatment or on a waitlist from National Health Service clinical psychology clinics in the UK. | Penn State Worry Questionnaire, BDI-II, N-Back Task, Random Generation Key-Pressing Task, Mood ratings, thought valence ratings, filler task and WTAR. | People with generalized anxiety disorder have fewer residual attentional control resources available during the worry process. Fewer resources were available to perform concurrent thinking tasks when individuals with anxiety were thinking about personally relevant topics. Verbal preoccupation takes less attentional control, suggesting that negative biases use resources. |

| Tempesta et al. (2013) [25] | Quantitative | Forty subjects between 20 and 35 years of age with a first episode of generalized anxiety from the Psychiatry Service for Diagnosis and Treatment, Hospital G. | STAI, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), PSQI, TAS-20 | Executive functions, as measured by the WCST, were affected in young subjects, immediate recall is also affected. Worry can interfere with the execution of some cognitive functions since it dedicates attentional resources to ruminant linguistic processing of threatening stimuli. Antidepressant treatment affects performance on sustained attention tasks, reducing the ability to remain alert for a long period of time. |

| White et al. (2017) [26] |

Quantitative | 78 participants 18-50 years of age (46 had generalized anxiety disorder and 32 were healthy subjects). | A passive avoidance task | Individuals with generalized anxiety disorder showed impaired reinforcement-based decision making. Lower correlation on the test between punishment and responses. They showed impaired reinforcement-based and worry about possible future consequences, such as illness or losing a job. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).