1. Introduction

Data visualizing are receiving more attention since they are easier to understand and summing up data. Dealing with big data poses a challenge with "curse of dimension" and computation capacity among other issues [

1]. Dimension reduction methods project the data dimensionality into a lower-dimensional space while retaining as much information as possible. These methods reduce the data storage and computation time, besides, overcome the complexity of the model. In recent decades, scientists have used various methods of machine learning (ML) to detect patterns and determine the intrinsic dimensions of big data to generate actionable insights, this could be handled by a range of dimension reduction methods. The set of techniques available for dimensionality reduction can be divided into techniques for supervised and unsupervised learning applications. Unsupervised methods aim to detect similarities and differences inside a dataset.

Principal component analysis (PCA) is one of the most popular dimension reduction methods [

2], it is also known as unsupervised method. The main purpose of PCA is to reduce the dimensionality of a data set consisting of a large number of interrelated variables while retaining as much as possible of the variation present in the data set. PCA was briefly mentioned by Fisher and Mackenzie [

3] as being more suitable than analysis of variance for the modelling of response data.

Fisher and Mackenzie [

3] also outlined the NIPALS algorithm, later rediscovered by Wold [

4]. Hotelling [

5] further developed PCA to its present stage. Since then, the utility of PCA has been rediscovered in many diverse scientific fields, resulting in, amongst other things, an abundance of redundant terminology. Rao [

6] paper is remarkable for the large number of new ideas concerning uses, interpretations and extensions of PCA that it introduced. Various fields apply PCA in applications such as: face recognition, handprint recognition, and mobile robotics. More applications are discussed in [

7].

The bootstrap method was introduced by Efron [

8]. It is a resampling technique for estimating the distribution of statistics based on independent observations, and then developed to work with other statistical inference. It is used for assigning the measures of accuracy of the sample estimate, especially the standard error. The bootstrap sample is obtained by randomly sampling n times with replacement from the original sample. In this paper, the bootstrap method is used to analyze the stability of PCA results and to estimate the number of PCA in efficient way. The method is used to estimate the number of PCA that needed to classify the data set. For a good introduction to the bootstrap method, see[

9]. The bootstrap method can be applied to with a lot of applications, such as tests, regression, and confidence intervals. And used as a useful statistical tool with clustering and mixture models [

10,

11]. Binhimd and Coolen [

12] introduced a new bootstrap method based on nonparametric predictive inference. It is called NPI-B. They compared between (NPI-B) and Efron's classical bootstrap method (Ef-B), then applied (NPI-B) for reproducibility of some statistical tests. Binhimd and Almalki [

13] discussed the comparison between Efron's bootstrap and smoothed Efron's bootstrap using different method. Some literatures discussed the work of bootstrapping principal component analysis [14, 15,16].

Practically, one needs to decide the number of components that need to be retained, which means measuring the stability of components or variables. In terms of statistical modelling, stability could be demanded that a data set drawn from the same underlying distribution should give rise to more or less the same parameter. It means that a meaningful valid parameter (component) should not disappear easily if the data set is changed in a non-essential way [

17]. Some of stability rules depend on computationally intensive, such as cross validation, bootstrap or jackknife. In the literatures, bootstrap used to estimate the confidence region for differentiable function of the covariance matrix of the original data, this is done after implementing PCA on the considered data. Another stability criterion, one based on a risk function which is known a distance between orthogonal projectors. The aim of this paper to study the stability of PCA method in such a way to improve the process of existing method and the effectiveness of the discussed techniques is demonstrated through a simulation study and real data sets.

2. Materials and Methods

This section provides a brief overview of the algorithms and procedures that will be used in the paper.

2.1. Principal Component Analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a dimension reduction method that projects the data with high dimensional space into a lower-dimensional sub-space. The new data can then be more easily visualized and analyzed, while retaining as much as possible of the data’s variation. It has applications in various fields, such as face recognition and image compression, it is a common technique for finding patterns in high-dimensional data.

Hence, let

be a random vector that has a probability density function

from a multivariate Gaussian distribution with mean and variance denoted by

and

, respectively. Assume that a sample of size

is drawn from the random vector

, yielding data

, which is N independent and identically distributed (iid) units. The matrix Z has the following structure:

The principal component analysis (PCA) method reduces a large number of associated variables into a manageable number of main components, which are independent linear combinations of those variables.

The main idea of PCA is to illustrate the variation that appears in a dataset that has correlated variable,

, then the new dataset of uncorrelated variables

, where each of

a linear combination of X. The variables in the new data are the principal components, where, the first principal component of the observation,

, is the linear combination:

Whose sample variance is greatest among all such linear combinations. Because the variance of can be increased without limit simply by increasing the coefficients , a restriction must be placed on these coefficients. As we shall see later, a sensible constraint is to require that the written

. The sample variance of that is a linear function of the variables is given by , where is the sample covariance matrix of the variables. To maximise a function of several variables subject to one or more constraints, the method of is used.

The second principal component,

, is defined to be the linear combination:

i.e.,

, where

and x =

that has the greatest variance subject to the following two conditions:

Usually, the total sum of eigenvalues that are obtained from a covariance matrix is equal to the total sum of variance of each variable.

2.2. Bootstrap

The bootstrap's primary tenet is that, in some circumstances, it is preferable to draw conclusions about a population parameter only from the available data, without making any assumptions about underlying distributions. Compared to traditional inferences, bootstrap approaches can often be considerably more correct. This method was developed to work with different statistical inferences, such as confidence intervals, hypothesis tests, and regression, it is good technique if the sample size is small. The basic method here depends on drawing B random samples of size n with replacement from the original sample, and then calculating the statistic of interest to estimate the sampling distribution and work with the required statistical inference. The issue with the method is that each time we gather a sample, we can receive somewhat different findings. The standard deviation of a point estimate for repeated population samplings theoretically may be quite high, which could bias the estimate.

2.3. Principal Components Analysis with bootstrap confidence interval

The extent to which the estimator is likely to diverge from the parameter must be determined in order to build a confidence interval for the parameter. The main premise behind the bootstrap is to assess how much the estimate swings when it is calculated using resampled versions of the original data.

2.4. Approaches using bootstrap

The bootstrap sample is drawn at random from the original, size N sample with replacement. Construct the bootstrap confidence interval:

The maximum eigenvalue can be found by repeatedly resampling dataset of (B) times. Using the resampled dataset I's covariance matrices.

The difference between the true and bootstrap eigenvalues (d) should be calculated.

A 0.025 percentile and a b=0.975 percentile of d are needed to calculate the confidence interval 95%. The appropriate confidence interval is (true-b, true+a).

3. Results

This section explains the implementation of bootstrap method in PCA on the selected data, Protein and Chemical data sets. The section offering a discussion across the following subsections:

Section 3.1 presents the results of Protein data;

Section 3.2 presents the results of Chemical data.

3.1. Protein data

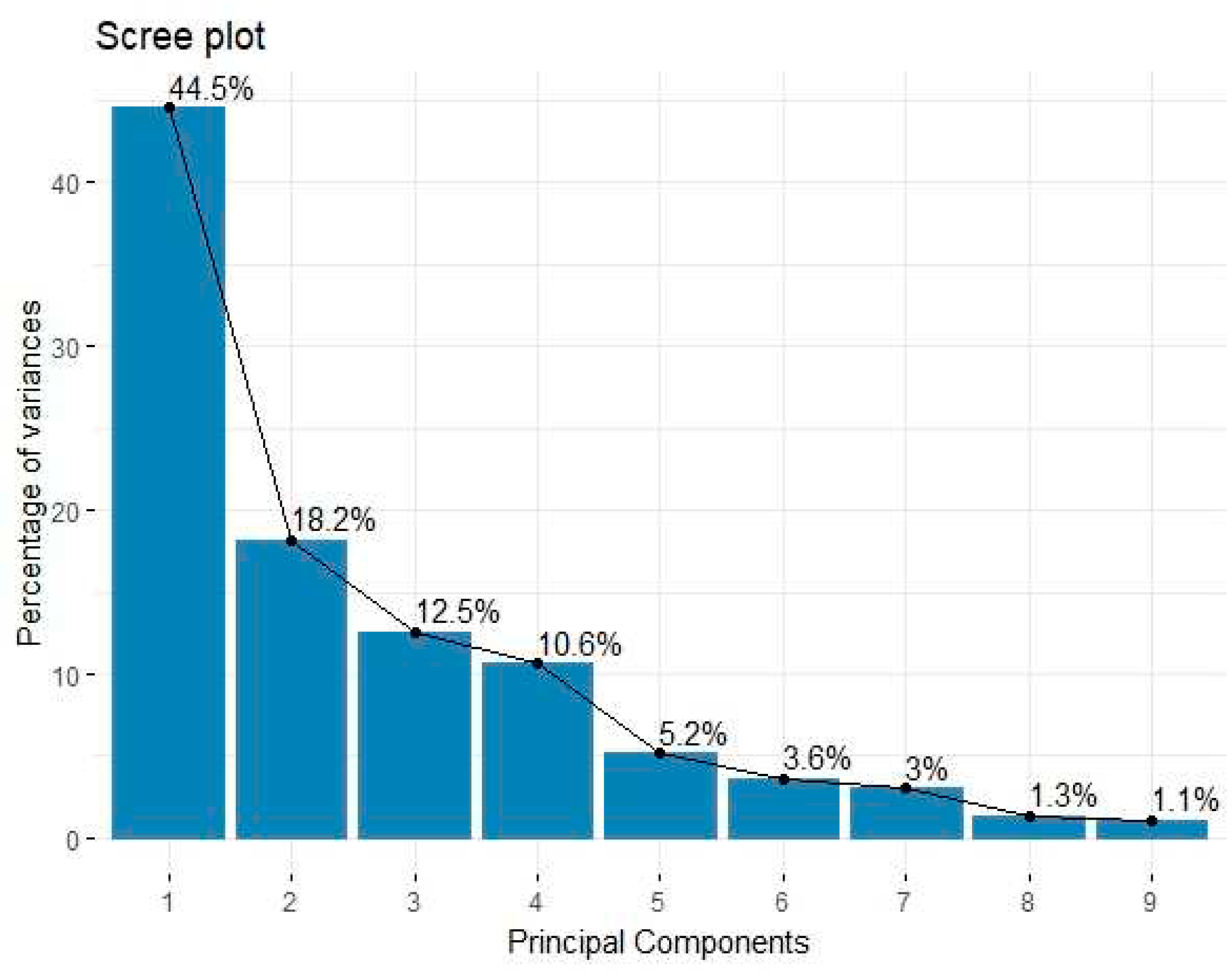

Protein consumption data consists of 25 rows of observations and 11 variables, the data is collected from 25 European countries for 9 kinds (groups) of foods Gabriel (1981). As first step, the PCA is implemented on this data to insight the data structure and conduct its variability, result is shown in

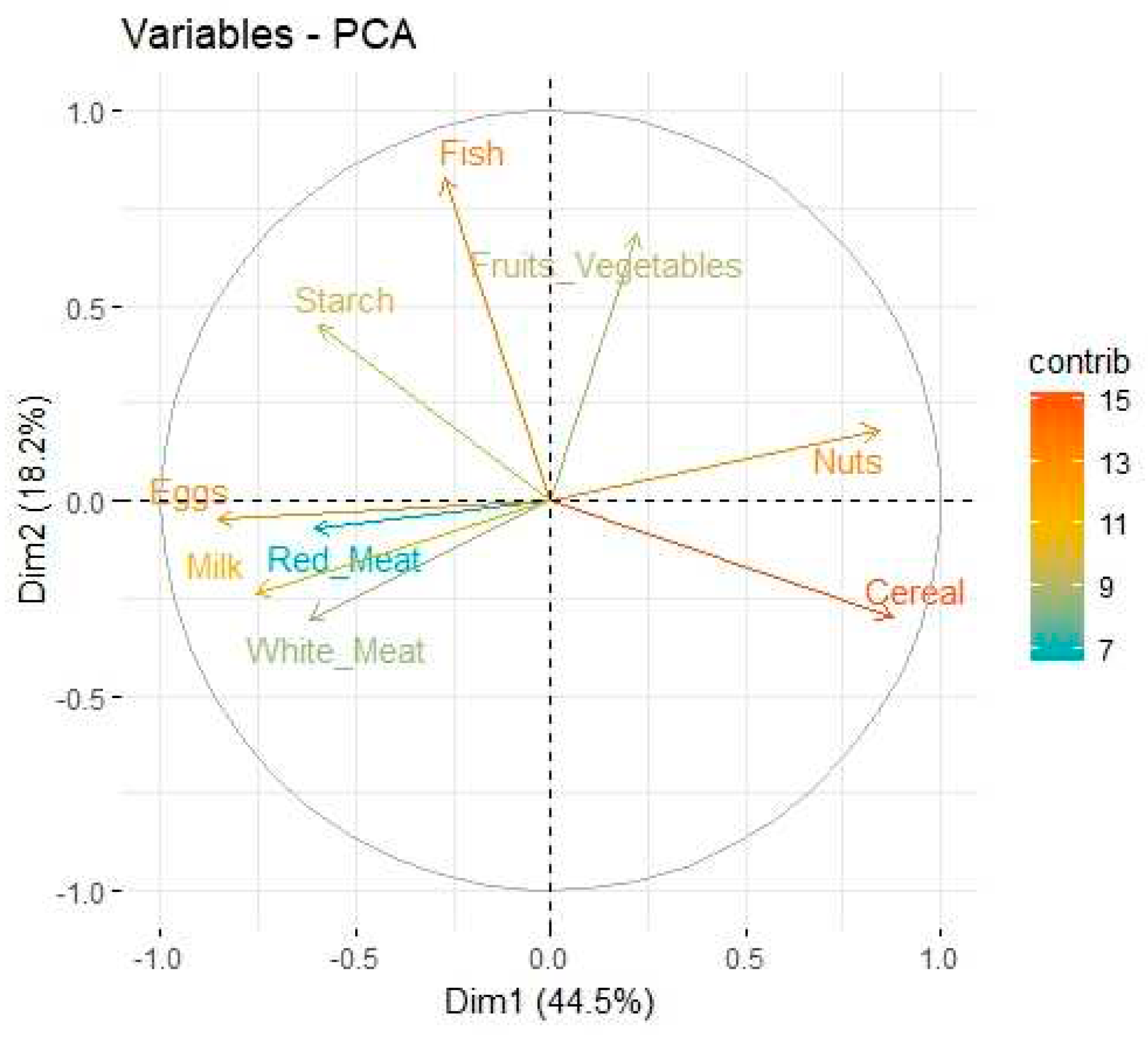

Figure 1. It presents that 91% of the total variance is explained by five components, with PC1 explaining 44.5% of the total variance, and PC2 explaining 18.2% of the total variance. PC3 further explains 12.5% of the total variance, PC4 and PC5 explaining 10.6% and 5.2%, respectively, of the total variance. This offers a perspective on these components’ comparative relationships to the dataset, with just five PCs explaining 91.43% of the total variance. To evaluate the relationship between the multiple variables and the relevant PCs,

Table 1 illustrates the squared factor loading for each variable, the total percentage of the variance that can be explained by the two components is around 62.7%. Consider the variables Red_Meat, White_Meat, Eggs, Milk, Fish, Cereal, Starch, Nuts and Fruits_Vegetables, we shall represent them by

, respectively. As illustration in Eq. (5) and Eq. (6), one can infer that highest contributing variables in PC1 are Cereal and Nuts while Eggs provides the highest negative level of contribution. In PC2, the highest contributing variables are Fish and Fruits_Vegetables while Eggs provides a low negative level of contribution.

Hence, the bootstrap on PCA is implemented on the data. The type of bootstrap is nonparametric method with 1000 Bootstrap samples that were drawn. Then, projection of the original matrix is done onto the bootstrap principal components, the results are discussed as follows.

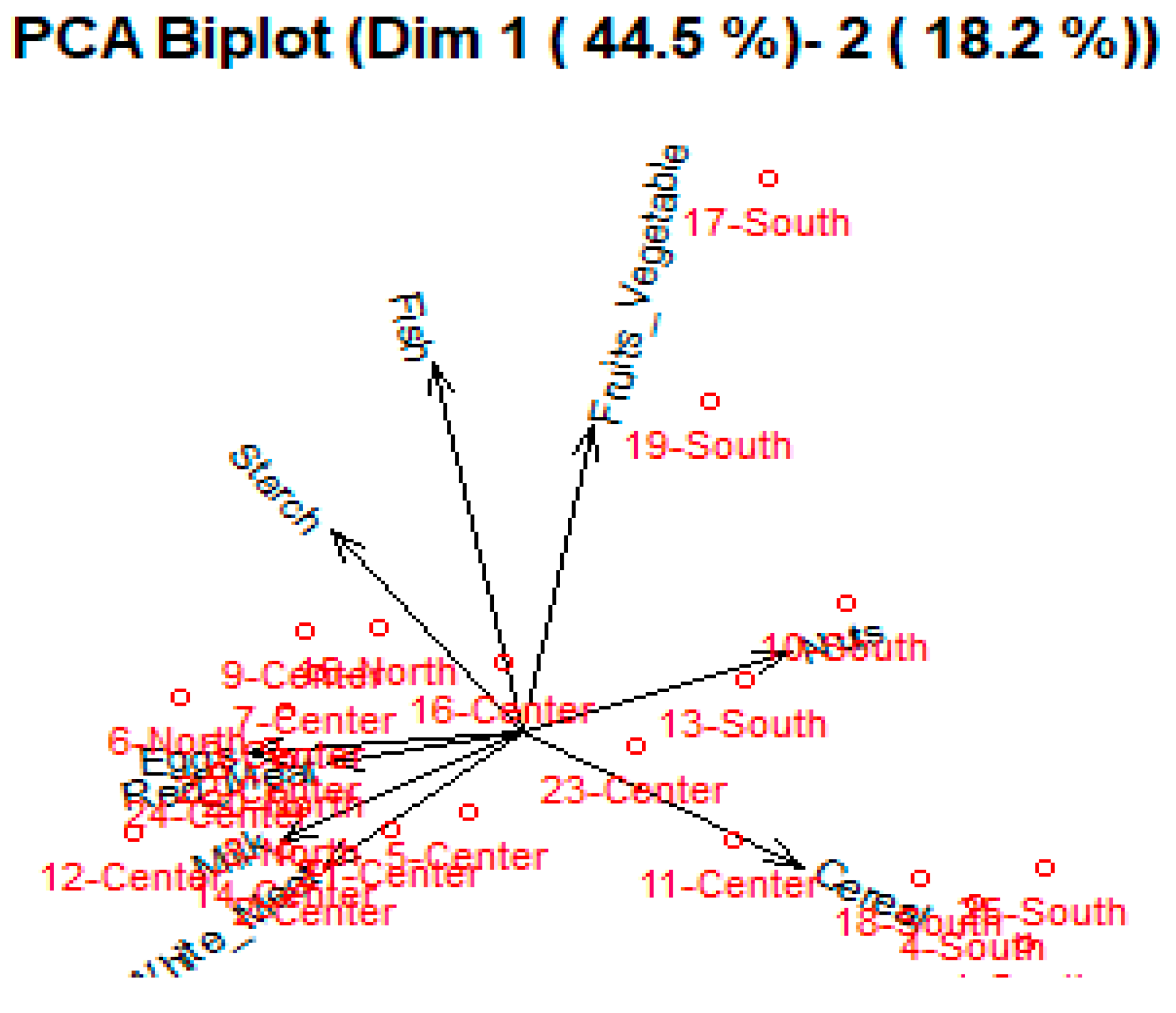

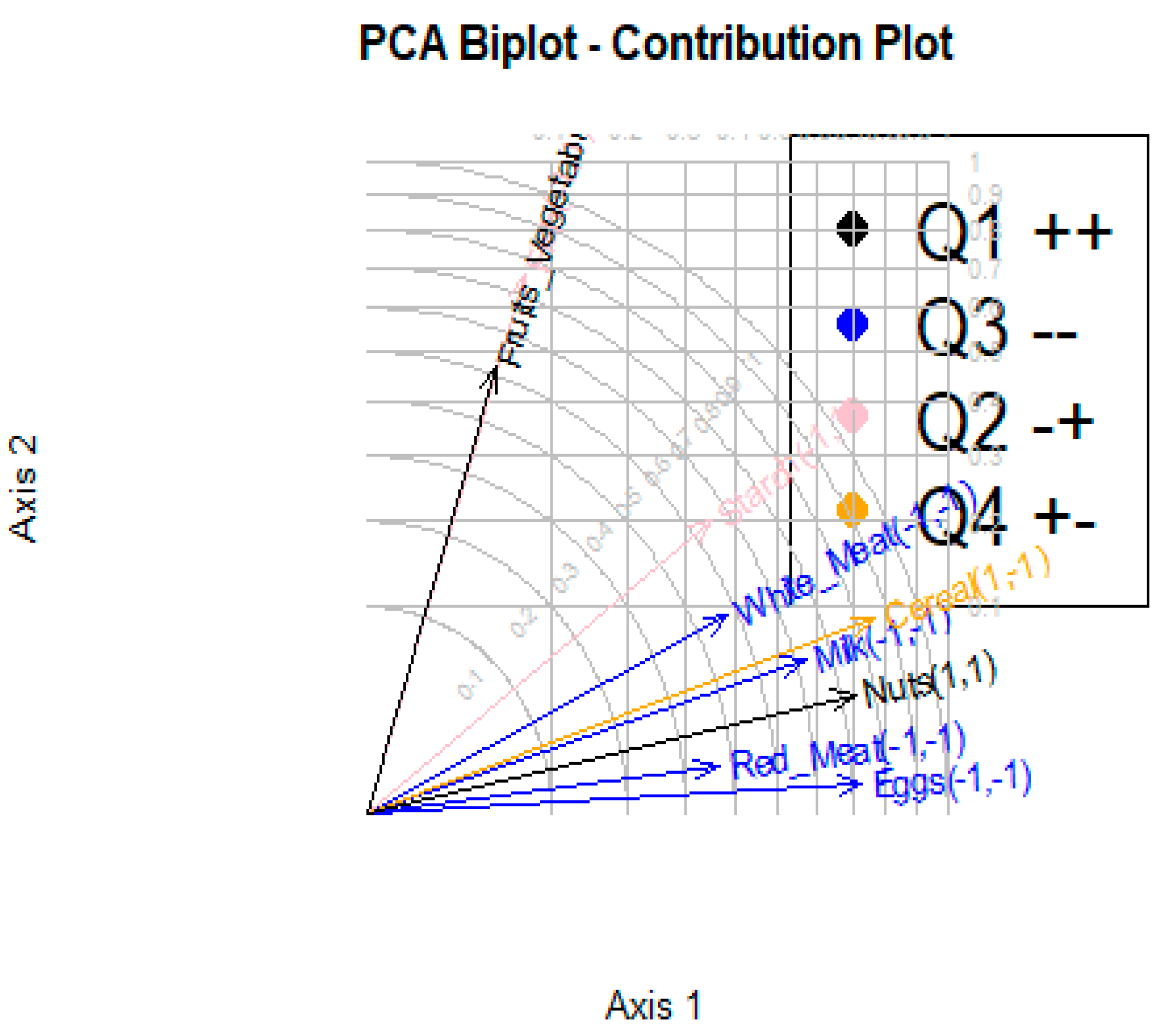

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 shows the observations as points in the plane formed by two principal components (synthetic variables), with the original variables appearing as vectors. The figures thus represent the interactions between variables, as well as highlighting the consistency of variable representation and the association between variables and measurements. Some factors are positively connected, such as Cereal, Nuts and Fruit and vegetables, with a high correlation between Fish, Eggs and Cereal, as represented in

Figure 4.

In addition,

Table 2 displays a matrix containing the proportions of accounted variance (columns) for each bootstrap sample (columns). The bootstrap mean in our observed samples for PC1 is equal to 46.95. The

95% confidence interval around the estimate of the variance difference, between test and control population variances, is

. While the 95%

confidence interval around the estimate of the mean difference, between Test and control population means, is

. Now, with PC2, the bootstrap mean equals 19.77 and the

95% confidence interval of the mean difference and variance difference are

and

, respectively.

3.2. Chemical data

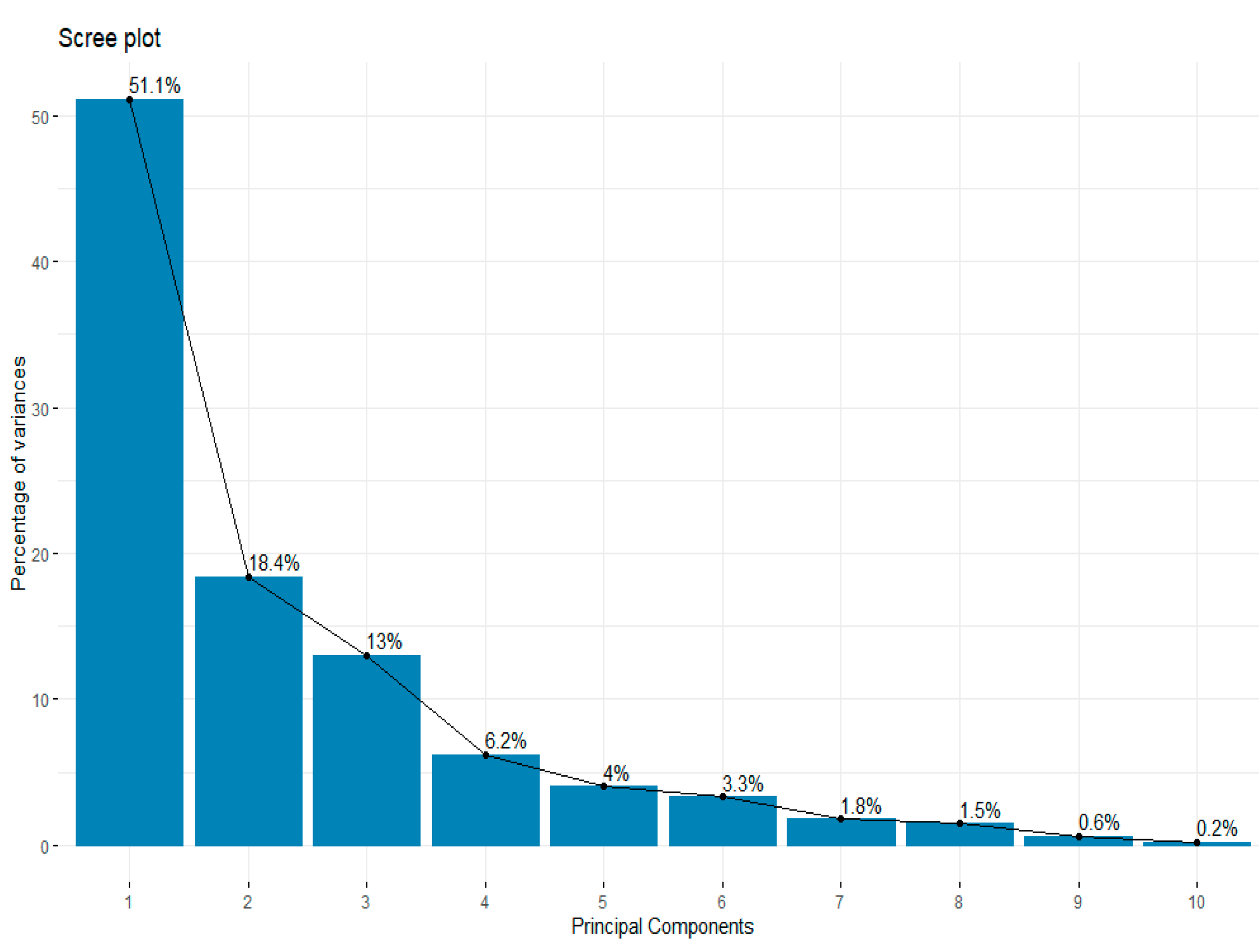

Chemical data is an ecological data collected by Department of Ecology at the University of Leon, (Spain), and available in R package. The data consists of 324 observations and 16 variables. As first step, the PCA is implemented and the result is shown in

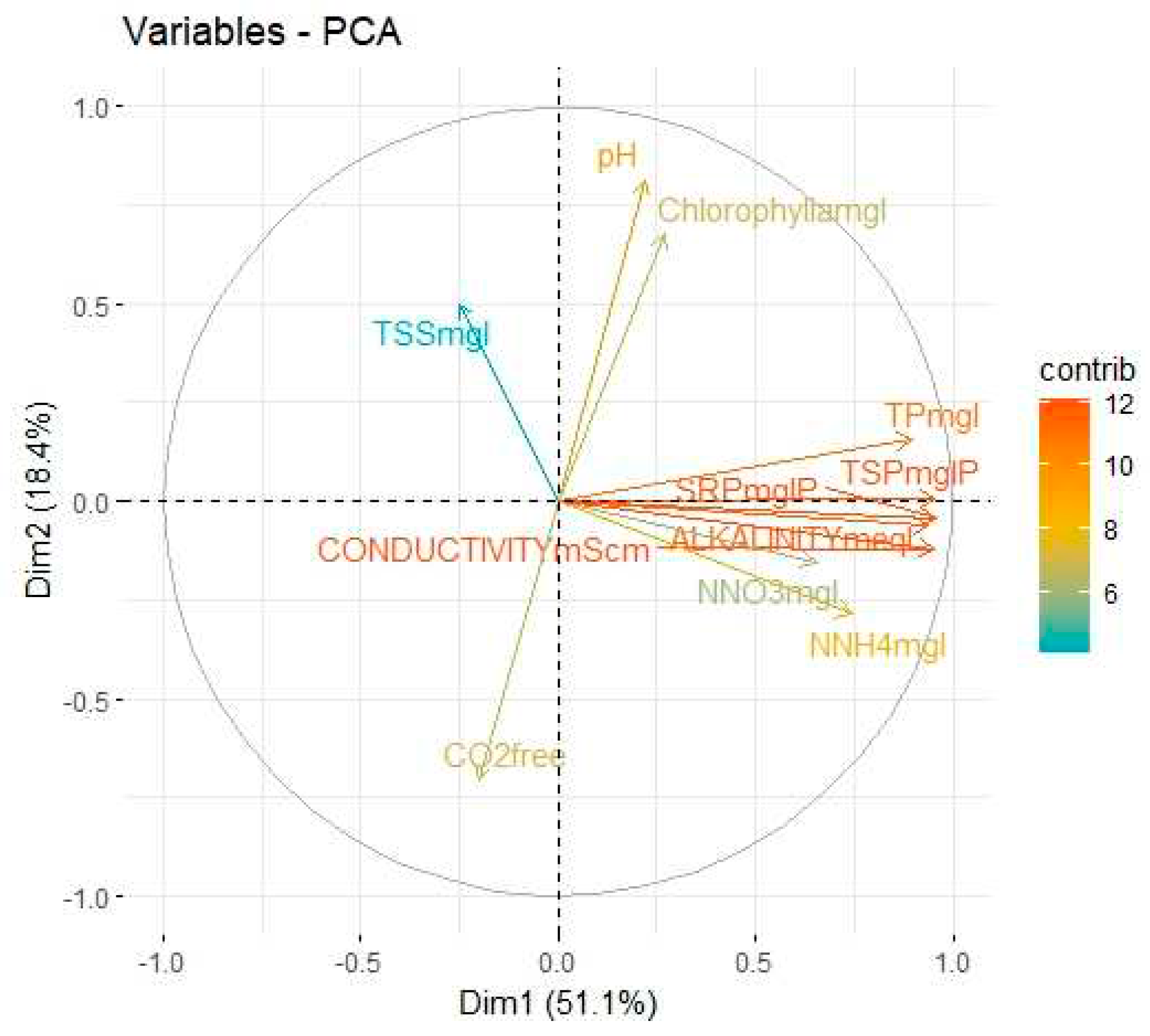

Figure 5 It presents that 92.7% of the total variance is explained by five components, with PC1 explaining 51.1% of the total variance, and PC2 explaining 18.4% of the total variance. PC3 further explains 13% of the total variance, PC4 and PC5 explaining 6.2% and 4%, respectively, of the total variance. This offers a perspective on these components’ comparative relationships to the dataset, with just five PCs explaining 92.7% of the total variance. To evaluate the relationship between the multiple variables and the relevant PCs,

Table 3 illustrates the squared factor loading for each variable, the total percentage of the variance that can be explained by the two components is around 69.5%. Consider the variables pH, ALKALINITYmeql, CO2free, NNH4mgl, NNO3mgl, SRPmglP, TPmgl, TSSmgl, CONDUCTIVITYmScm, TSPmglP and Chlorophyllamgl as represented by

,

respectively. As illustration in Eq. (10) and Eq. (11), one can infer that highest contributing variables in PC1 are SRPmglP and TSPmglP while TSSmgl provides the highest negative level of contribution. In PC2, the highest contributing variables are pH and Chlorophyllamgl while SRPmglP provides a low negative level of contribution.

As we did earlier in the protein data, the bootstrap on PCA is implemented on the data the results are discussed as follows.

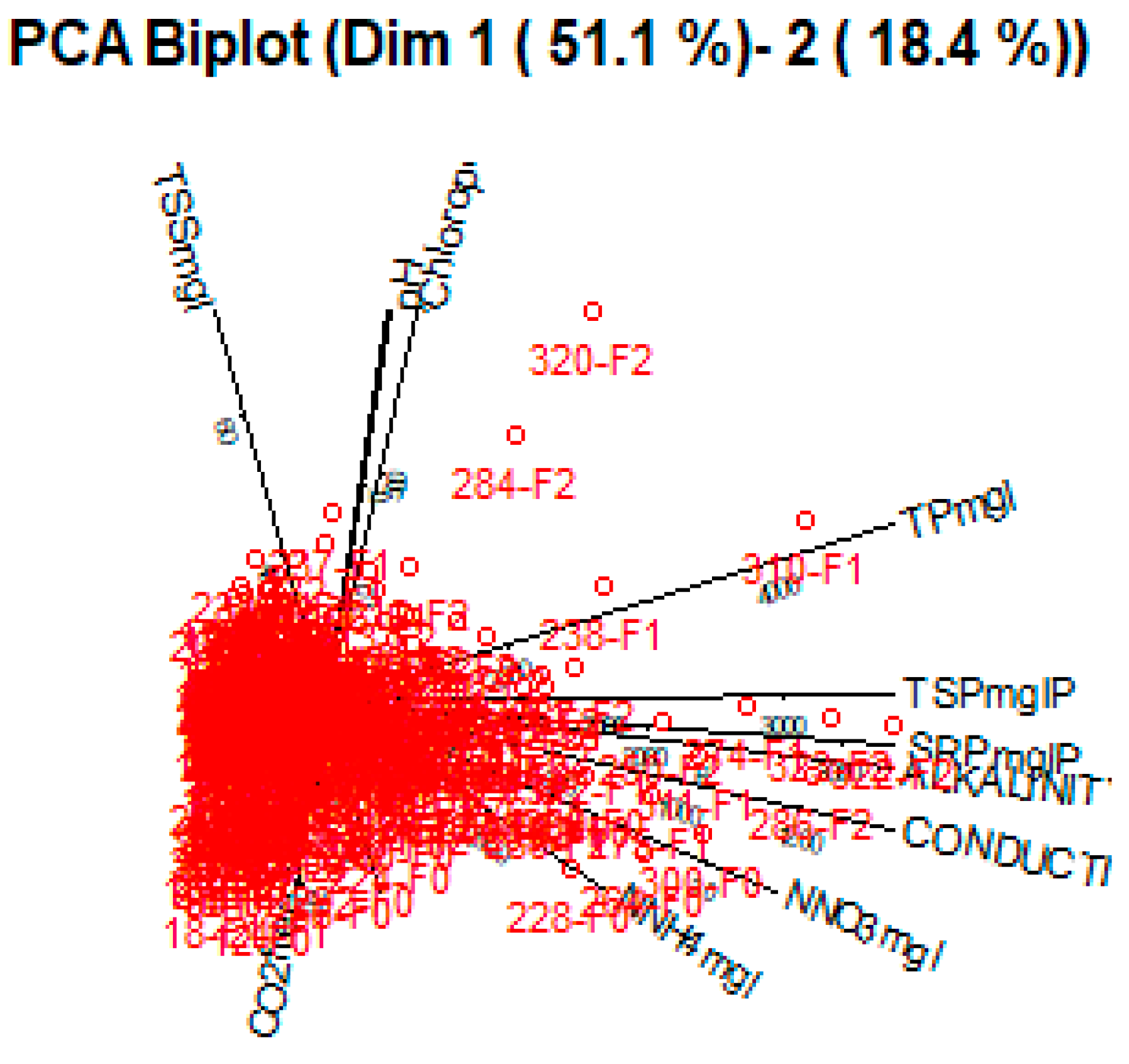

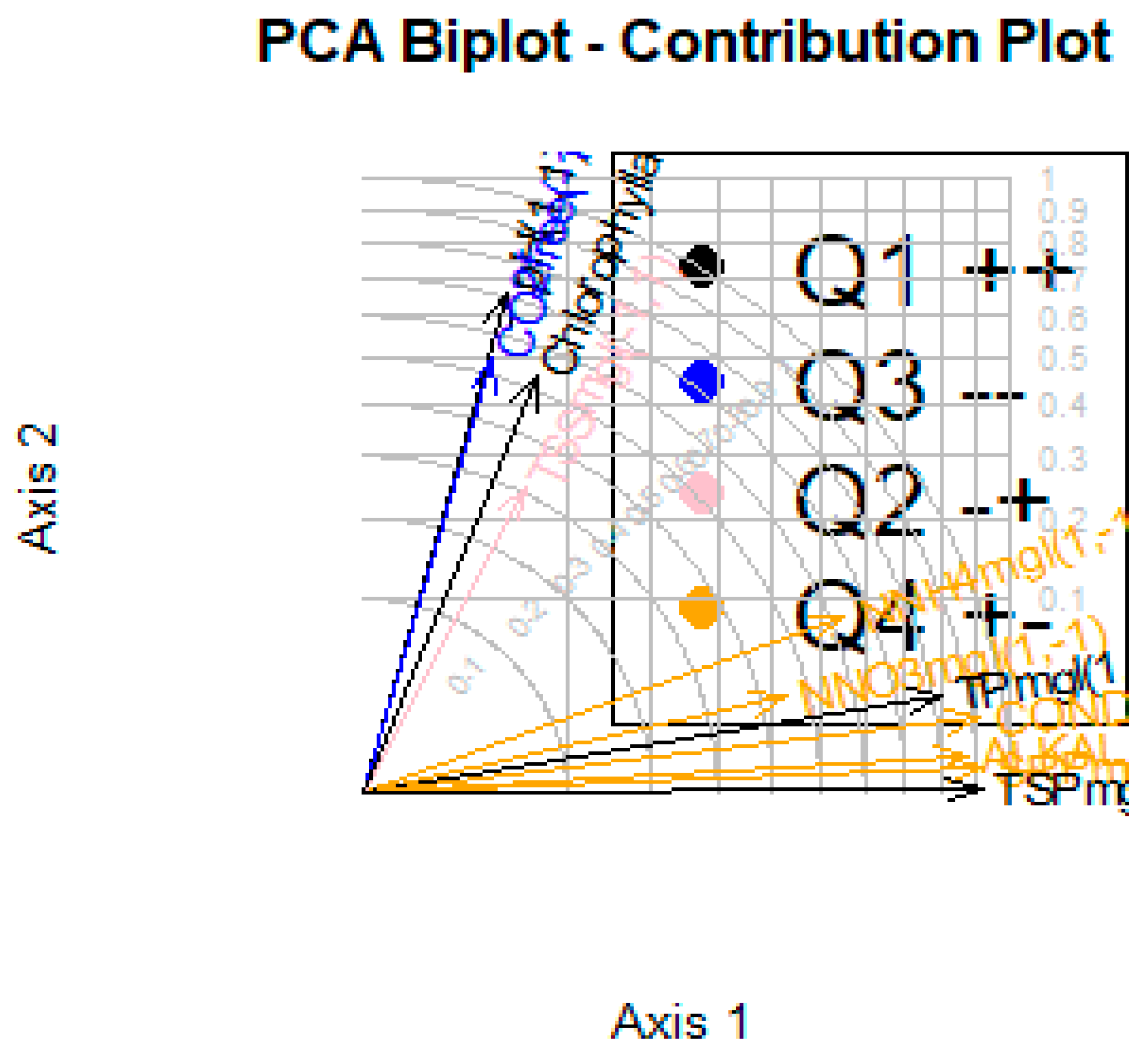

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 shows the observations as points in the plane formed by two principal components (synthetic variables), with the original variables appearing as vectors. The figures thus represent the interactions between variables, as well as highlighting the consistency of variable representation and the association between variables and measurements. Some factors are positively connected, such as

NNH4mgl, NNO3mgl, SRPmglP, TPmgl, CONDUCTIVITYmScm and TSPmglP, with a high correlation in between, as represented in

Figure 8.

In addition,

Table 4 displays a matrix containing the proportions of accounted variance (columns) for each bootstrap sample (columns). The bootstrap mean in our observed samples for PC1 is equal to 51.32. The

95% confidence interval around the estimate of the variance difference, between test and control population variances, is

. While the 95%

confidence interval around the estimate of the mean difference, between Test and control population means, is

. Now, with PC2, the bootstrap mean equals 18.465 and the

95% confidence interval of the mean difference and variance difference are

and

, respectively.

4. Discussion

This paper has covered Principal component analysis and bootstrap method and their stability in data analytics employing the correlation matrix have all been explored. The visualization of PCA illustrates its expectations in the part of parameter uncertainties. As shown by results of Protein and chemical datasets the using of confidence limits based on the bootstrap method provides meaningful statements and answers that to be preferred over all matches situations.

Author Contributions

The authors equally contributed to the present paper.

Funding

This work was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant No. D-046-247-1439. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR technical and financial support.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our great appreciation to the editors and reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Einbeck, J.; Kalantan, Z.; Kruger, U. Practical Considerations on Nonparametric Methods for Estimating Intrinsic Dimensions of Nonlinear Data Structures. International Journal of Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence 2020. Vol. 34, No. 9, 2058010.

- Pearson, K. LIII. On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 1901, 2(11), 559-572.

- Fisher, R.; Mackenzie, W. Studies in crop variation. II. The manurial response of different potato varieties, Journal of Agricultural Science 1923, 13 (1923) 311-32.

- Wold, H. (1973). Nonlinear estimation by iterative least squares procedures, in F. David (Editor), Research Papers in Statistics, Wiley, New York, 1966, pp. 411-444.

- Hotelling, H. (1933) Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. Journal of Educational Psychology, 24, 417-441.DOI.org/10.1037/h0071325.

- Rao, Y. (1964). Multivariate Statistical Data Analysis- Principal Component Analysis (PCA). DOI: 10.5455/ijlr.20170415115235. [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, N. and Kalantan, Z.I. (2020). Gaussian Mixture Models Based on Principal Component and Application. Mathematical Problems in Engineering. Hindawi. Vol.2020. ID 1202307. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1202307. [CrossRef]

- Efron, B (1979). Bootstrap methods: Another Look at the Jackknife. The Annals of Statistics,7, 1-26. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4612-4380-9_41. [CrossRef]

- Efron, B., & Tibshirani, R. (1993). An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman and Hall. DOI:10.1201/9780429246593. [CrossRef]

- Jaki, T., Su, T., Kim, M., & Lee Van Horn, M. (2017). An Evaluation of the bootstrap for model validation in mixture models. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation, 0, 1-11. DOI:10.1080/03610918.2017.1303726. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y., & Wang, J. (2012). Selection of the number of clusters via the bootstrap method. Computation Statistics and Data Analysis,56, 468-477. DOI: 10.1016/j.csda.2011.09.003. [CrossRef]

- Binhimd, S., & Coolen, F. (2020). Nonparametric Predictive Inference Bootstrap with Application to Reproducibility of the Two-Sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test. Journal of Statistical Theory and Practice. DOI:10.1007/s42519-020-00097-5. [CrossRef]

- Binhimd, S., & Almalki, B. (2019). Bootstrap Methods and Reproducibility Probability. American Scientific Research Journal for Engineering, Technology, and Sciences (ASRJETS).

- Daudin, J. J., Duby, C., & Trecourt, P. (1988). Stability of principal component analysis studied by the bootstrap method. Statistics: A journal of theoretical and applied statistics, 19(2), 241-258.

- Chateau, F., & Lebart, L. (1996). Assessing sample variability in the visualization techniques related to principal component analysis: bootstrap and alternative simulation methods. In COMPSTAT: Proceedings in Computational Statistics 12th Symposium held in Barcelona, Spain, 1996 (pp. 205-210). Physica-Verlag HD.

- Linting, M., Meulman, J. J., Groenen, P. J., & Van der Kooij, A. J. (2007). Stability of nonlinear principal components analysis: An empirical study using the balanced bootstrap. Psychological methods, 12(3), 359.

- Hennig, C. (2007). Cluster-wise assessment of cluster stability. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 52(1), 258-271.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).